Submitted:

22 April 2024

Posted:

25 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Work

1.2. Contributions

- We propose a representation of distinct uncertainty and distinct information, which is used to demonstrate the unexpected behavior of the measure by Williams and Beer [1] (Section 2.2 and Section 3).

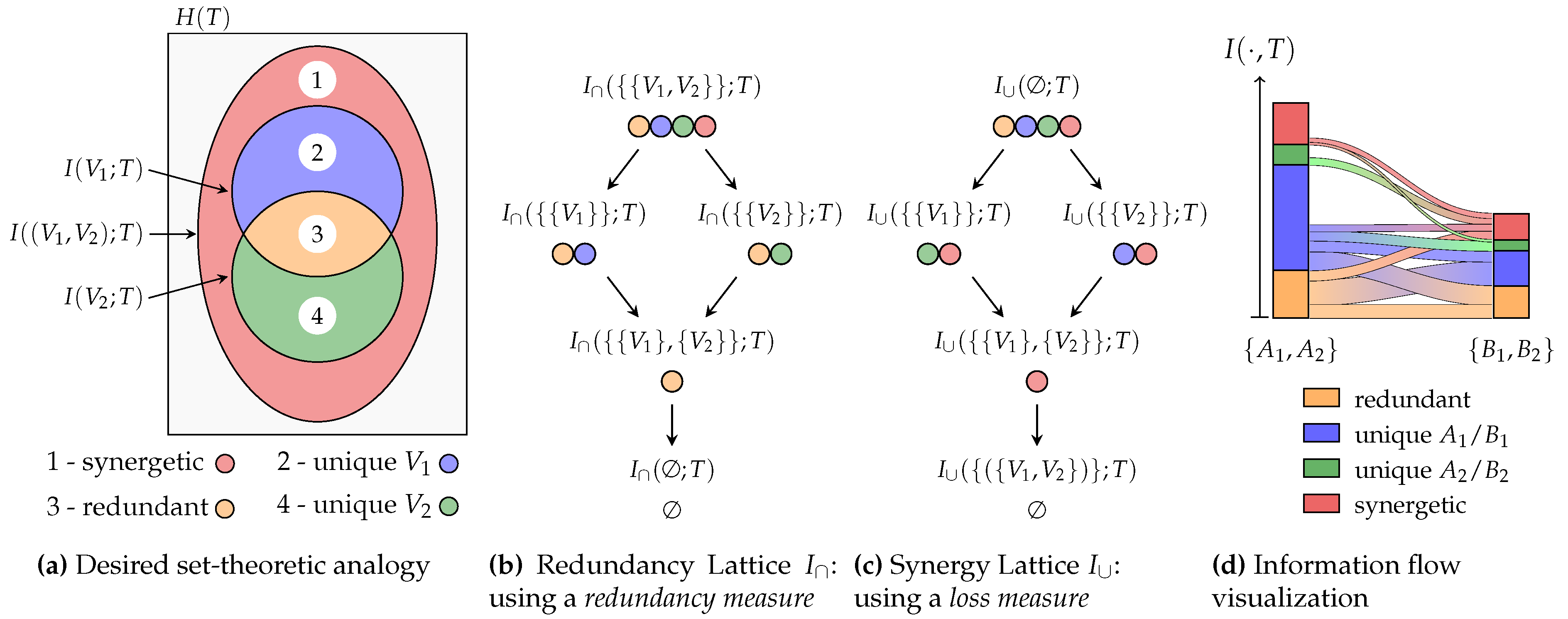

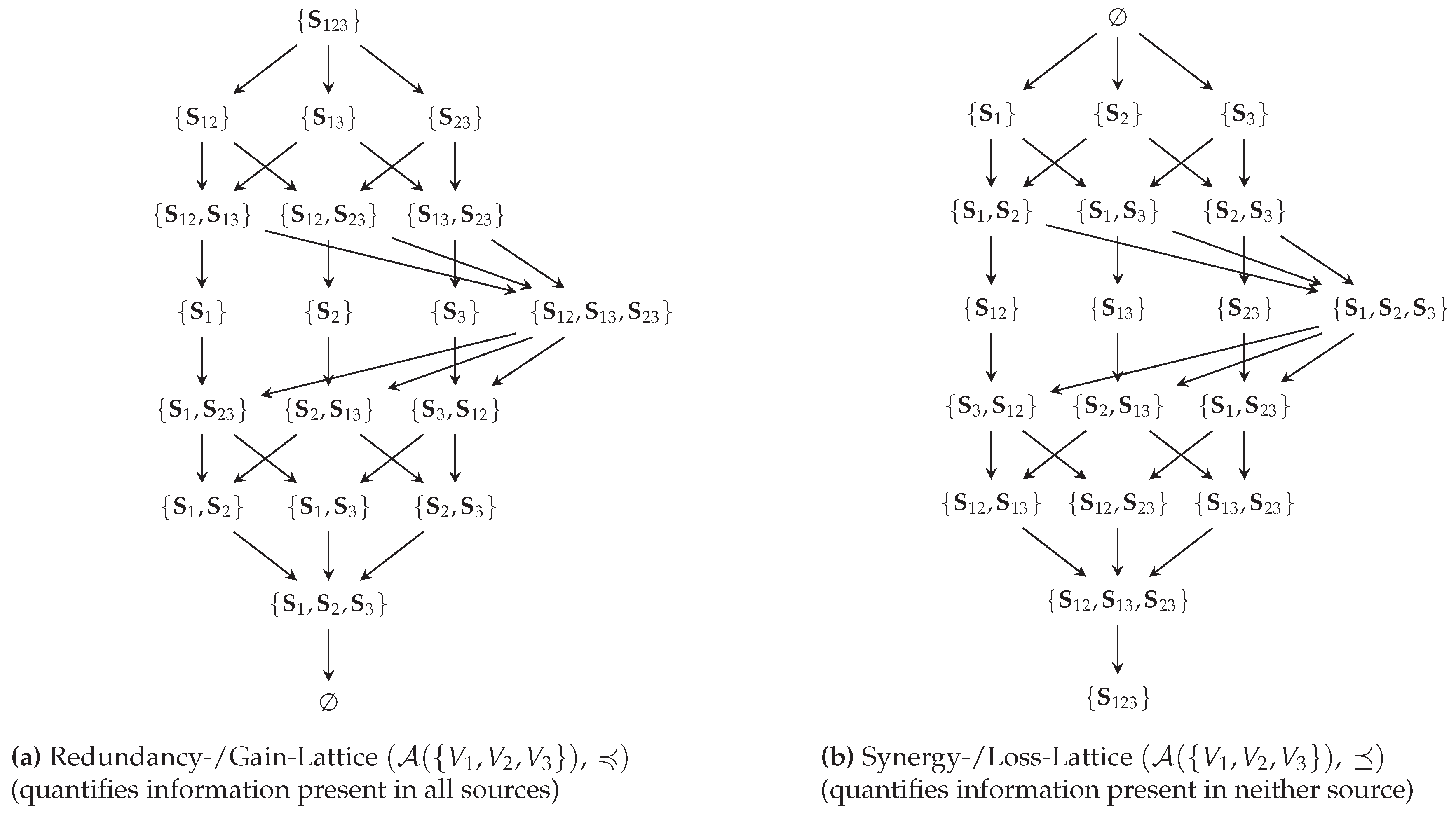

- We propose a decomposition for any f-information on both the redundancy lattice (Figure 1b) and synergy lattice (Figure 1c) that satisfies an inclusion-exclusion relation and provides a meaningful operational interpretation (Section 3.2).

- We prove that the proposed decomposition satisfies the original axioms of Williams and Beer [1] and guarantees non-negative partial information (Theorem 3).

- We propose to transform the non-negative decomposition of one information measure into another. This transformation maintains the non-negativity and its inclusion-exclusion relation under a re-definition of information addition (Section 3.3).

- We demonstrate the transformation of an f-information decomposition into a decomposition for Rényi- and Bhattacharyya-information (Section 3.3).

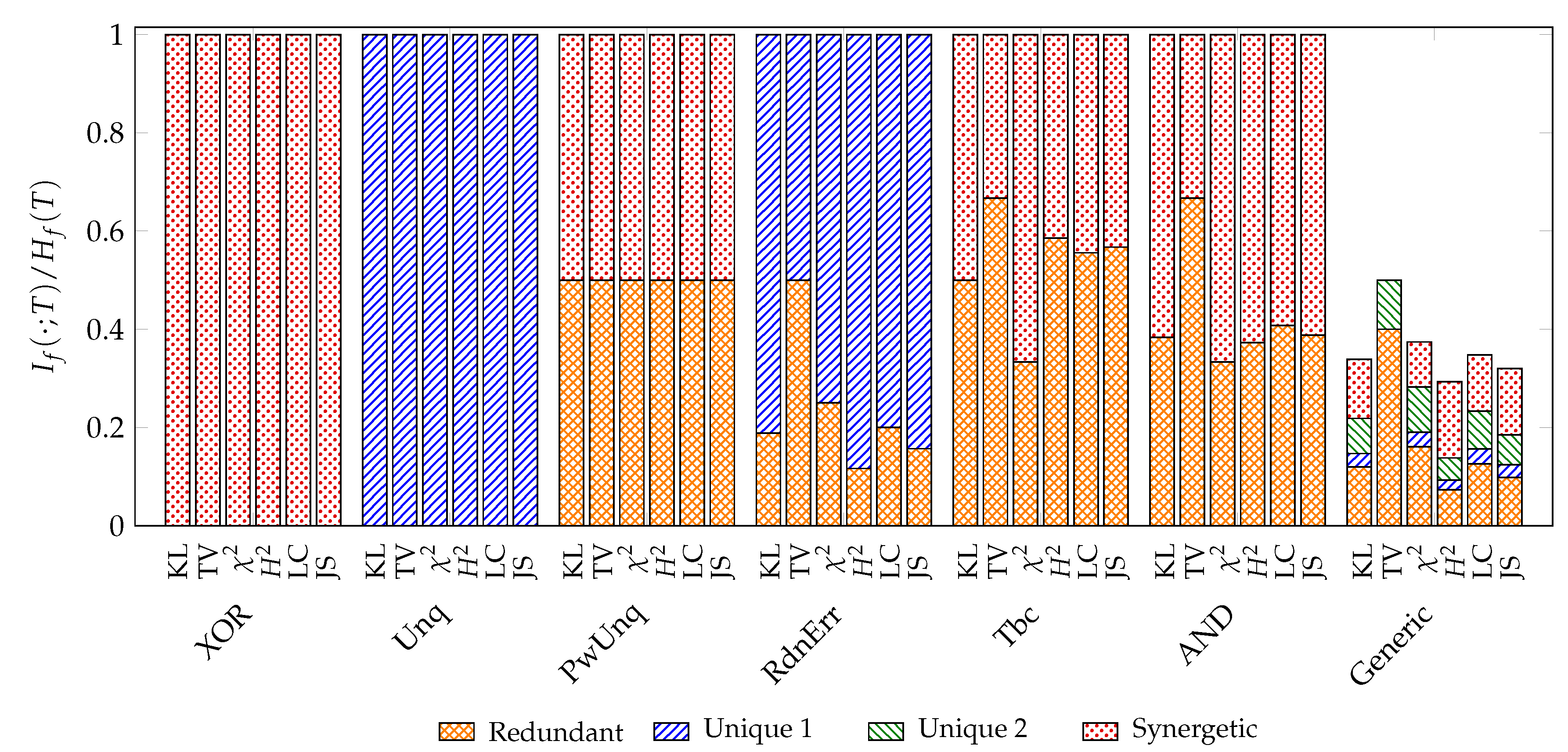

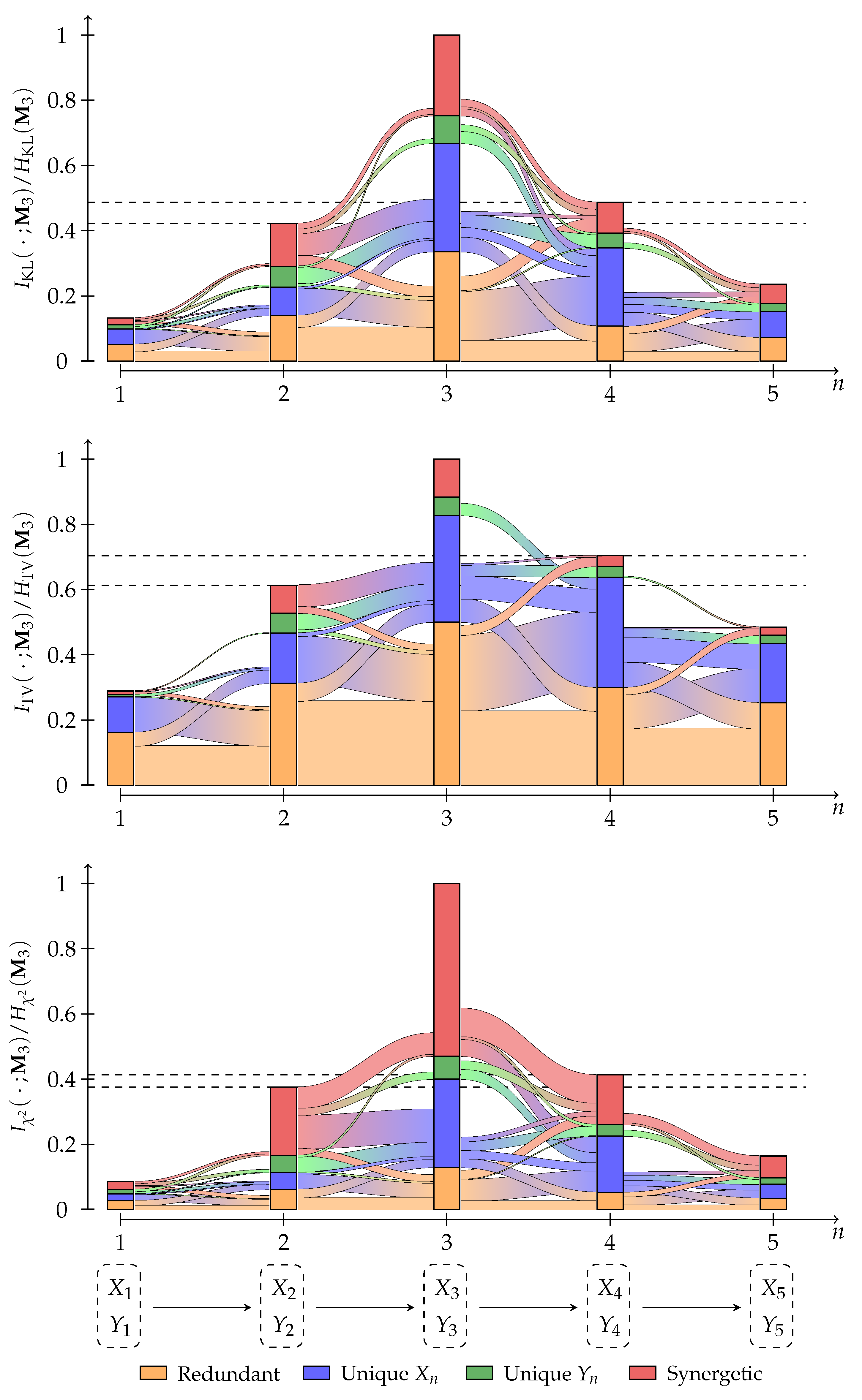

- We demonstrate that the proposed decomposition obtains different properties from different information measures and analyze the behavior of total variation in more detail (Section 4).

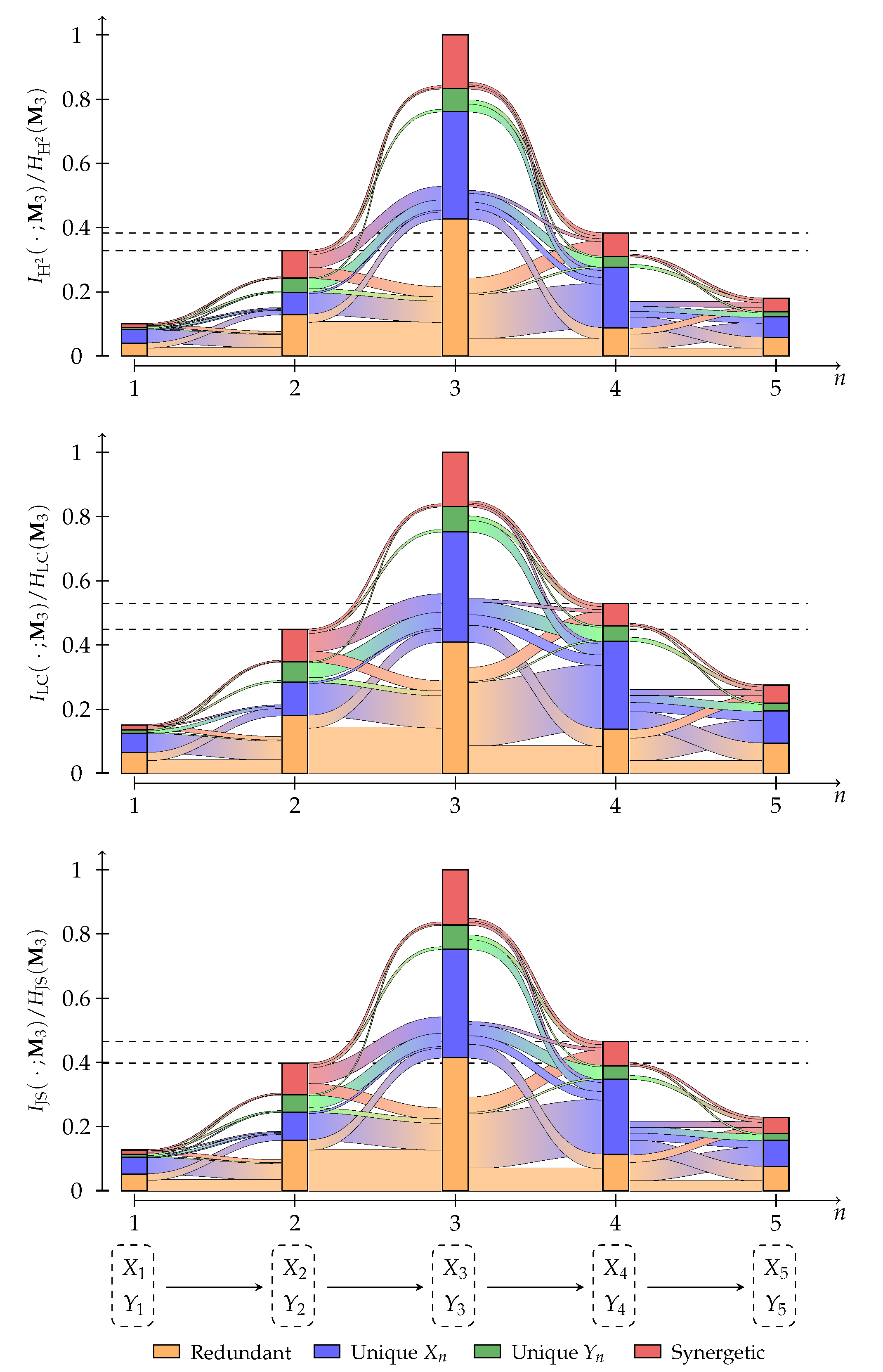

- We demonstrate the analysis of partial information flows through Markov chains (Figure 1d) for each information measure on both the redundancy and synergy lattice (Section 4.2).

2. Background

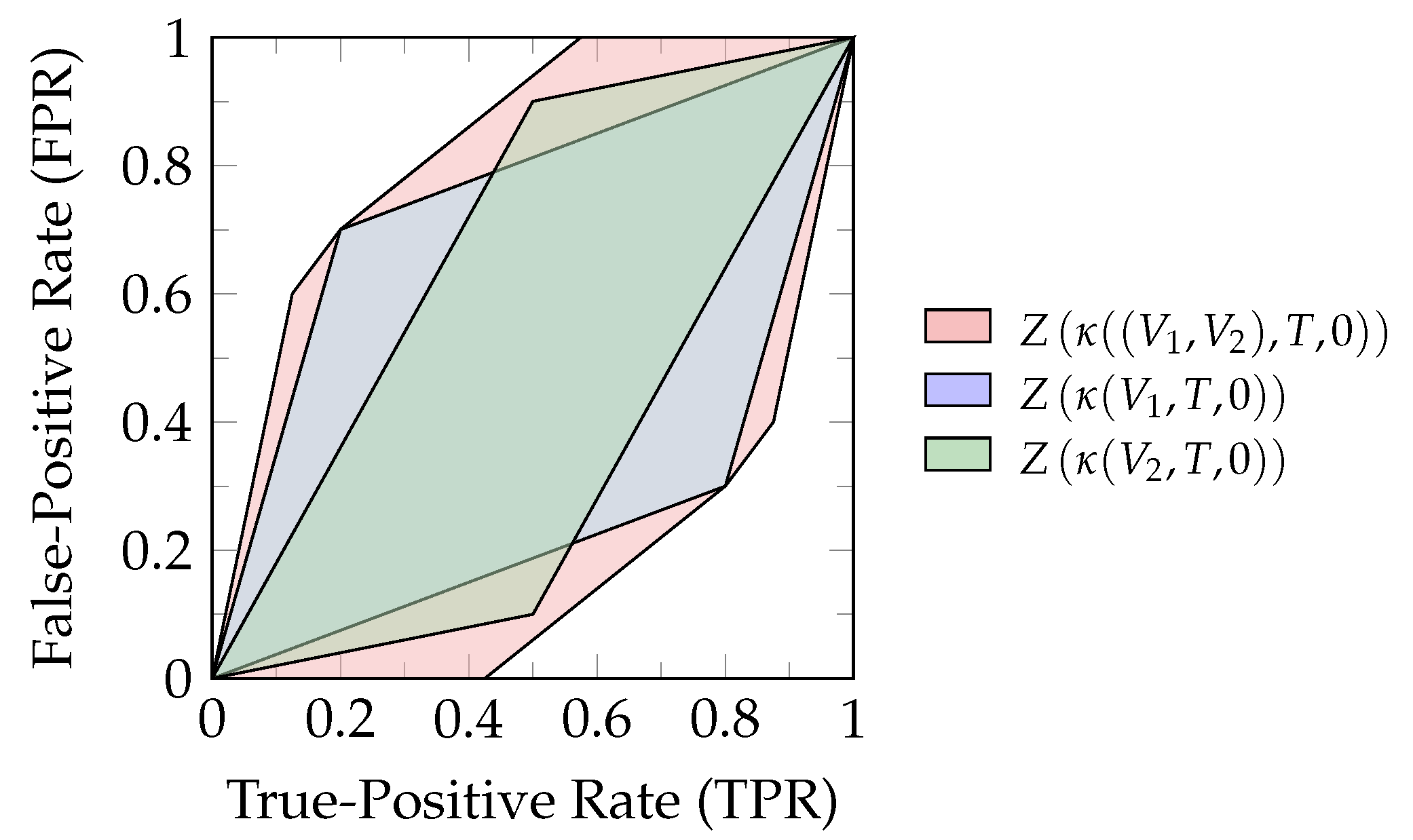

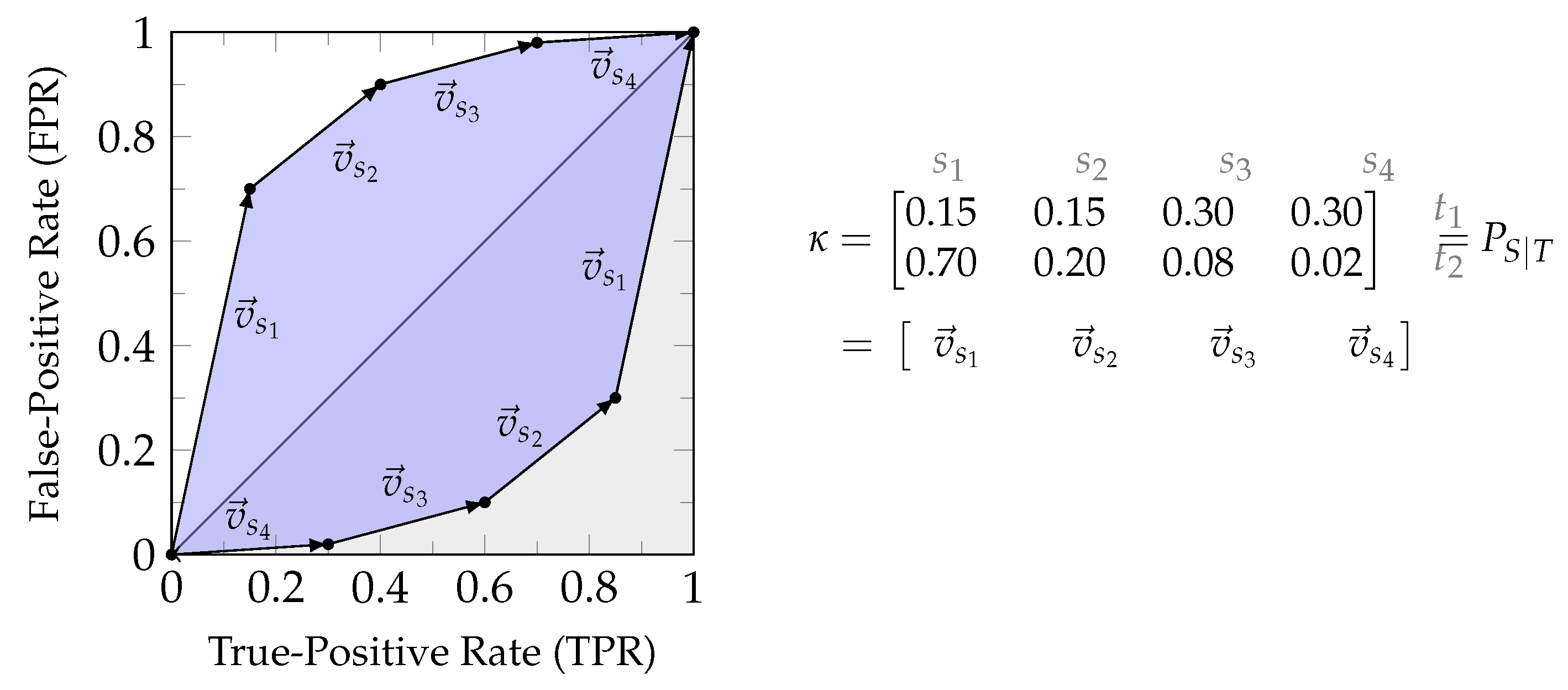

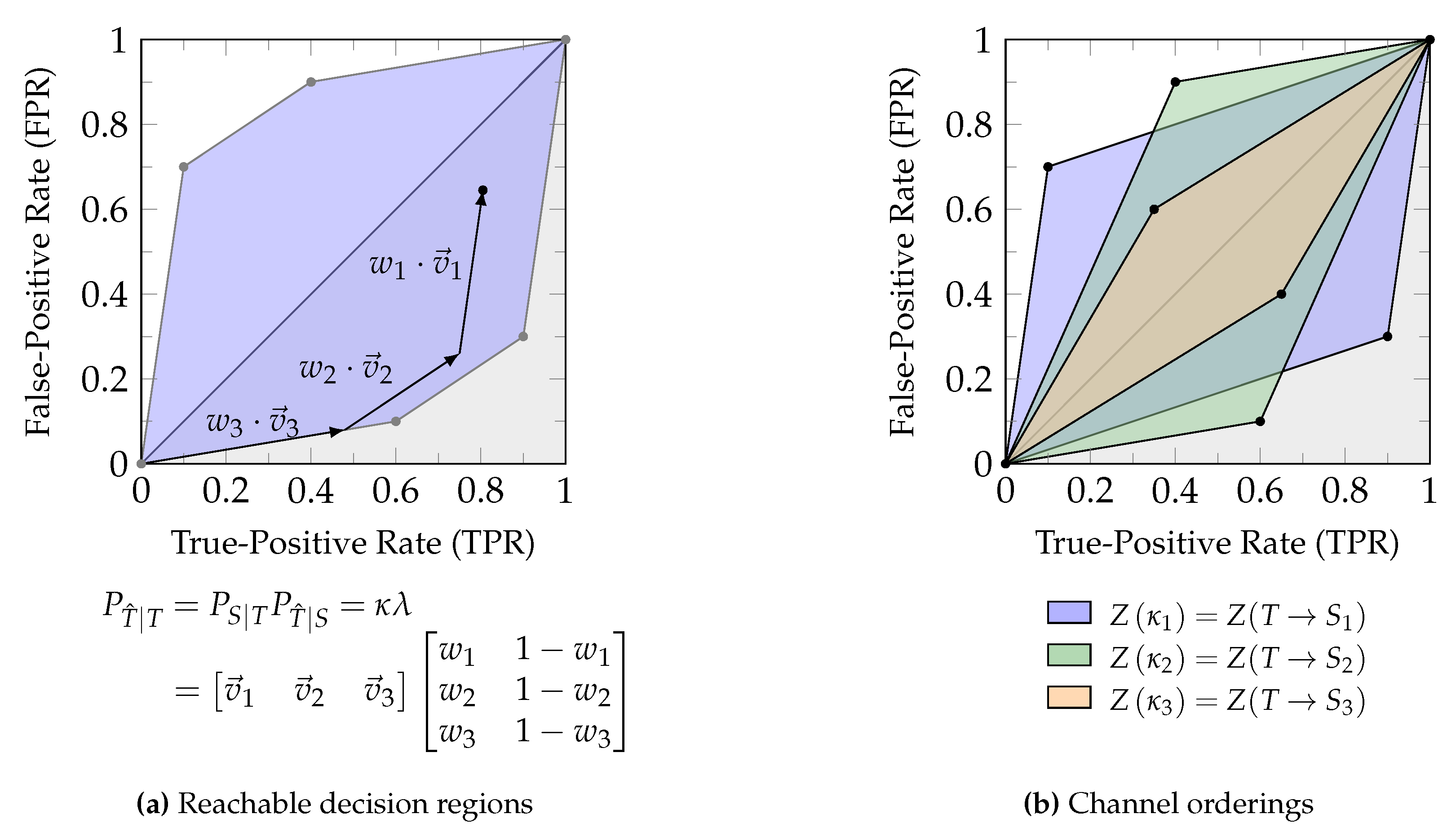

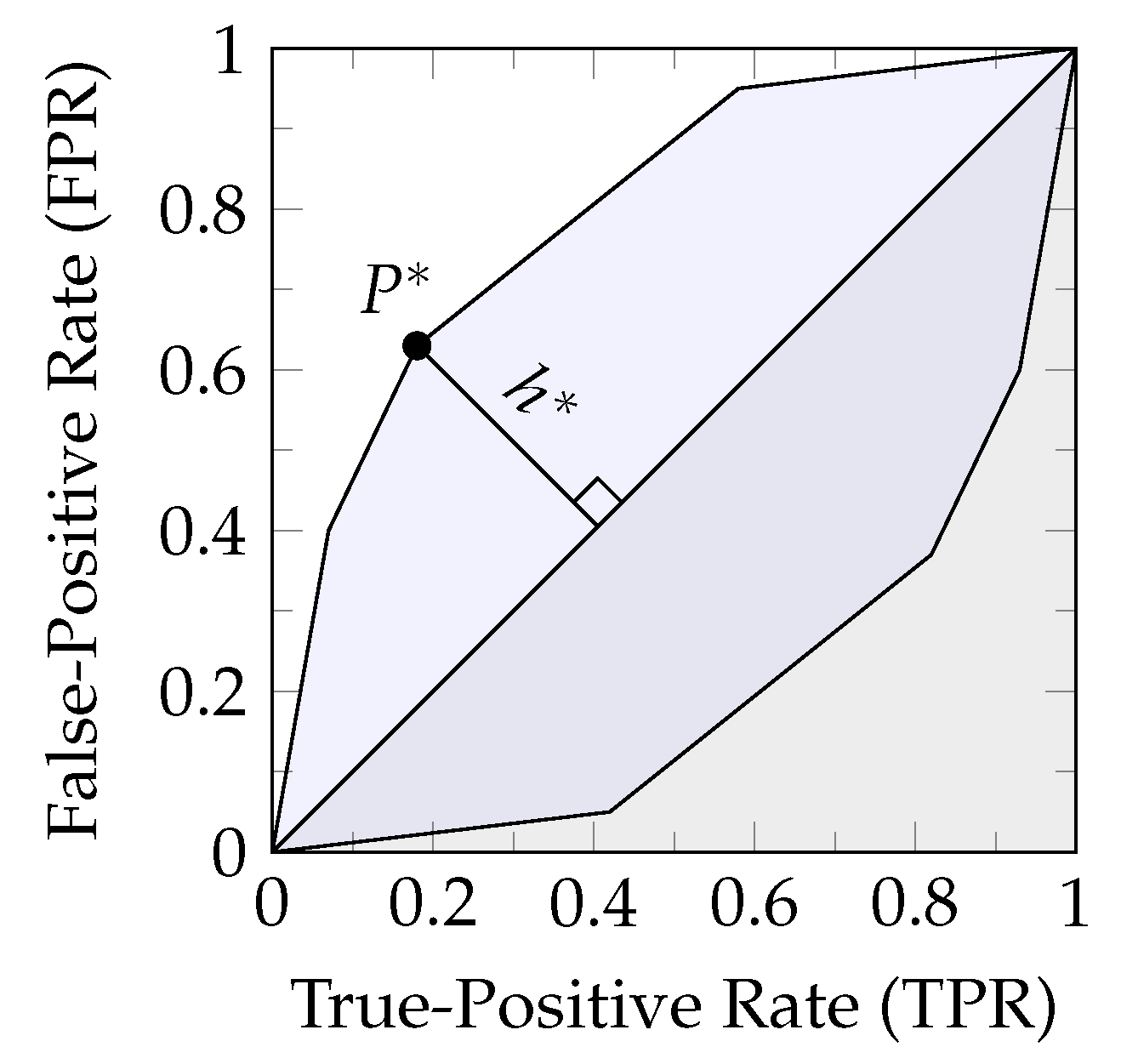

2.1. Blackwell and Zonogon Order

2.2. Partial Information Decomposition

- A source is a non-empty set of visible variables.

- An atom is a set of sources constructed by Equation 8.

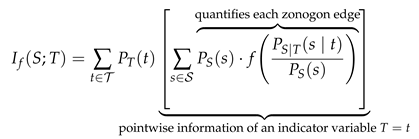

2.3. Information Measures

- f is convex,

- ,

- is finite for all .

3. Decomposition Methodology

- In a similar manner to how Finn and Lizier [13] used probability mass exclusion to differentiate distinct information, we use Neyman-Pearson regions for each state of a target variable to differentiate distinct information.

- We propose applying the concepts about lattice re-graduations discussed by Knuth [19] to PIDs to transform the decomposition of one information measure to another while maintaining its consistency.

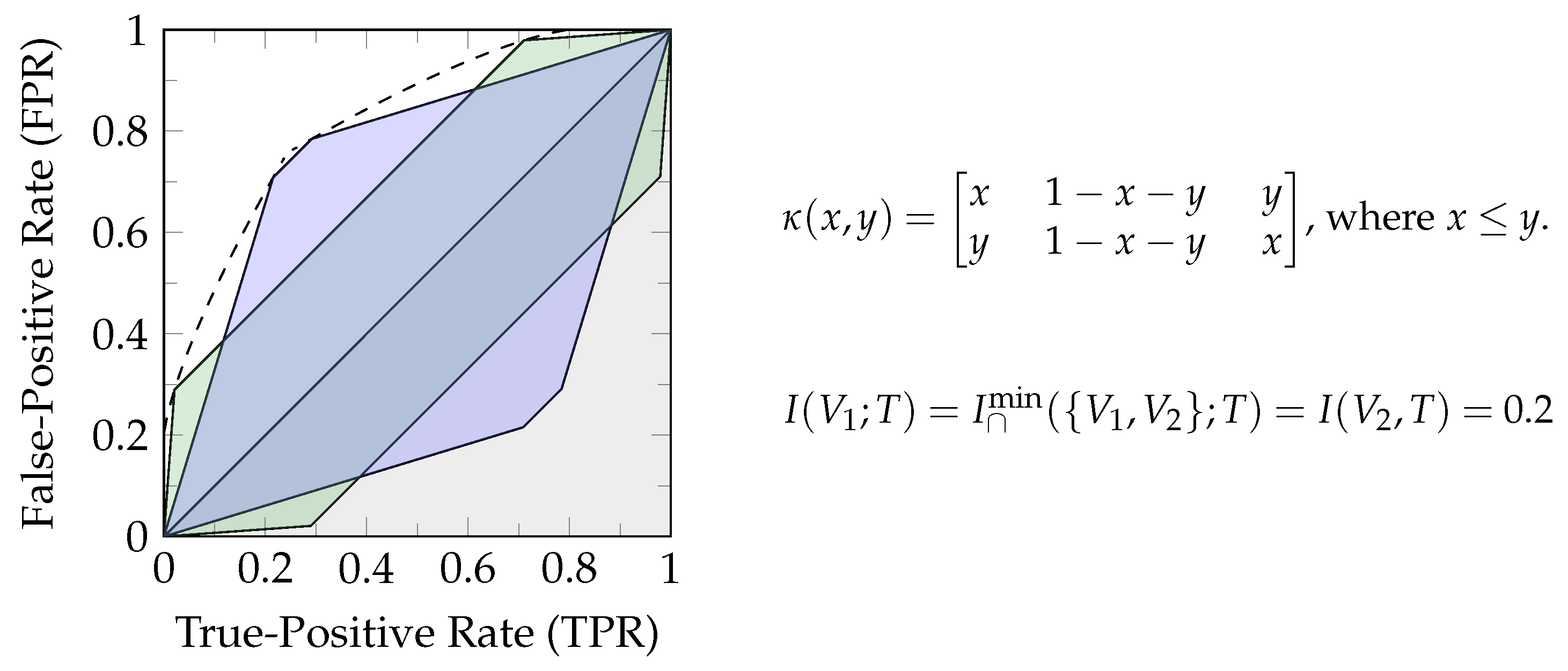

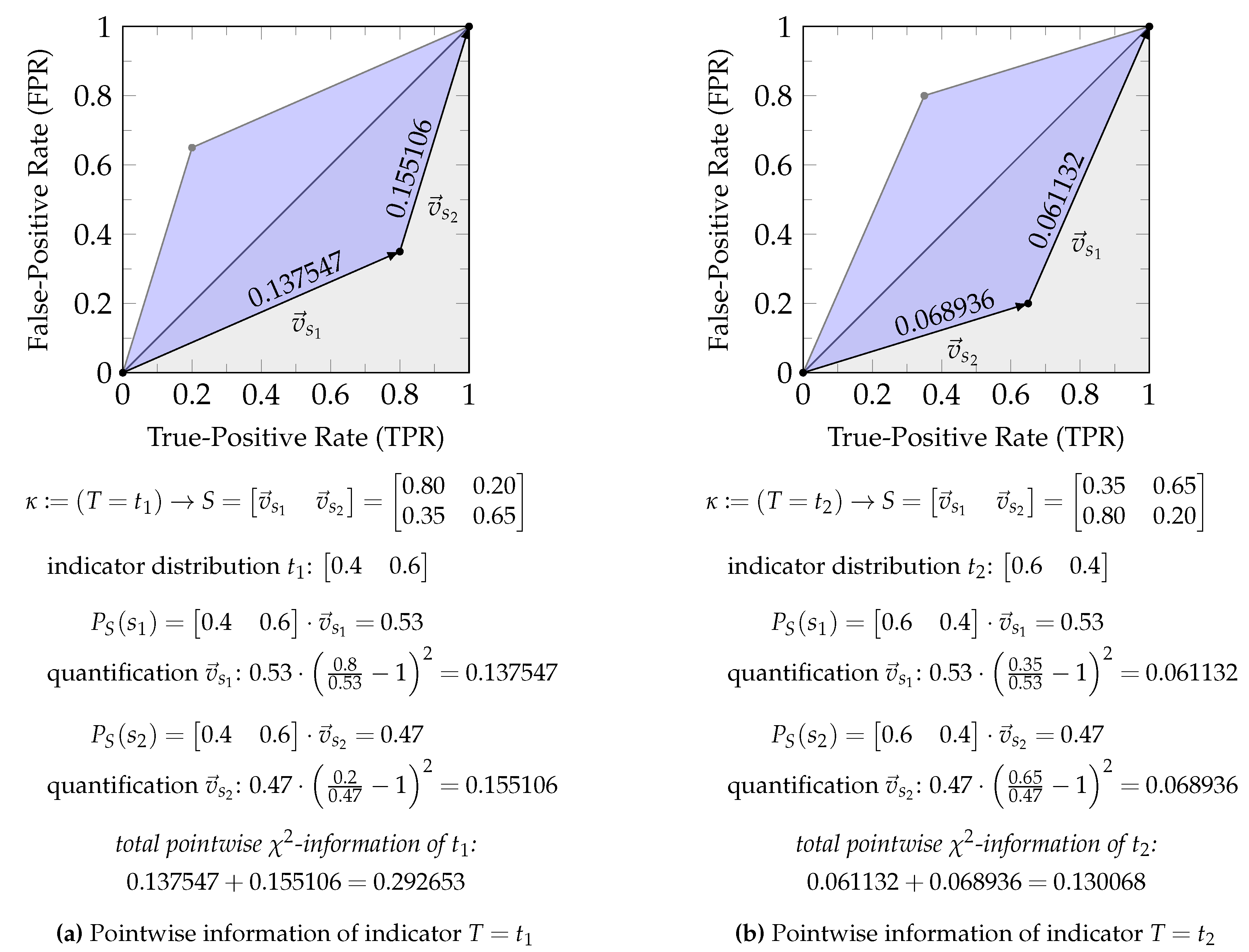

3.1. Representing f-Information

- We define a function as shown in Equation 27a to quantify a vector, where .

- We define a target pointwise f-information function , as shown in Equation 27b, to quantify half the zonogon perimeter for the corresponding pointwise channel .

- 1.

- The convexity of in is shown separately in Lemma A1 of Appendix A.

- 2.

- That scales linearly in can directly be seen from Equation 27a.

- 3.

- The triangle inequality of in is shown separately in Corollary A1 of Appendix A.

- 4.

- A vector of slope one is quantified to zero , since is a requirement on the generator function of an f-divergence (Definition 15).

- 5.

- The zero vector is quantified to zero by the convention of generator functions for an f-divergence (Definition 15).

- 1.

- That the function maintains the ordering relation of the Blackwell order on binary input channels is shown separately in Lemma A2 of Appendix A (Equation 28a).

- 2.

- The bottom element consists of a single vector of slope one, which is quantified to zero by Theorem 1 (Equation 28b). The combination with Equation 28a ensures the non-negativity.

3.2. Decomposing f-Information

- Axiom 1: The measure (Equation 32a) is invariant to permuting the order of sources in , since the join operator of the zonogon order () is. Therefore, also satisfies Axiom 1.

- Axiom 2: The monotonicity of both and on the synergy lattice is shown separately as Corollary A2 in Appendix B.

- Non-negativity: The non-negativity of and is shown separately as Lemma A7 in Appendix B.

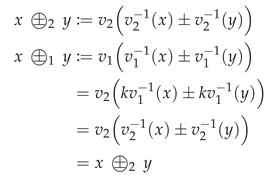

3.3. Decomposing Rényi-Information

- Axiom 1: is invariant to permuting the order of sources, since satisfies Axiom 1 (see Section 3.2).

- Axiom 2: satisfies monotonicity, since satisfies Axiom 2 (see Section 3.2) and the transformation function is monotonically increasing for .

- Axiom 4: Since satisfies Axiom 4 (see Section 3.2, Equation 36 and 38), satisfies the self-redundancy axiom by definition, however, at a transformed operator: .

- Non-negativity: The decomposition of is non negative, since is non-negative (see Section 3.2), the Möbius inverse is computed with transformed operators (Equation 39b) and the function satisfies .

4. Evaluation

4.1. Partial Information Decomposition

4.1.1. Comparison of Different f-Information Measures

4.1.2. The special case of total variation

- a)

- b)

- For a non-empty set of pointwise channels , pointwise total variation quantifies the join element to the maximum of its individual channels (Equation 42b).

- c)

- The loss measure quantifies the meet for a set of sources on the synergy lattice to their minimum (Equation 42c).

4.2. Information Flow Analysis

5. Discussion

- All information measures in Section 2.3 are the expected value of the pointwise information (quantification of the Neyman-Pearson region boundary) for an indicator variable of each target state. Therefore, we argue for acknowledging the “pointwise nature” [13] of these information measures and to decompose them accordingly. A similar argument was made previously by Finn and Lizier [13] for the case of mutual information and motivated their proposed pointwise partial information decomposition.

- The Blackwell order does not form a lattice beyond indicator variables since it does not provide a unique meet or join element for [17]. However, from a pointwise perspective, the informativity (Definition 2) provides a unique representation of union information. This enables separating the definition of redundant, unique and synergetic information from a specific information measure, which then only serves for its quantification. We interpret these observations as indication that the Blackwell order should be used to decompose pointwise information based on indicator variables rather than decomposing the expected information based on the full target distribution.

- We can consider where the alternative approach would lead, if we decomposed the expected information from the full target distribution using the Blackwell order: the decomposition would become identical to the method of Bertschinger et al. [9] and Griffith and Koch [10]. For bivariate examples (), this decomposition [9,10] is non-negative and satisfies an additional property (identity, proposed by Harder et al. [5]). However, the identity property is inconsistent [32] with the Axioms of Williams and Beer [1] and non-negativity for . This causes negative partial information when extending the approach to . The identity property also contradicts the conclusion of Finn and Lizier [13] from studying Kelly Gambling that “information should be regarded as redundant information, regardless of the independence of the information sources” ([13], p. 26). It also contradicts our interpretation of distinct information through distinct decision regions when predicting an indicator variable for some target state. We do not argue that this interpretation should be applicable to the concept of information in general, but acknowledge that this behavior seems present in the information measures studied in this work and construct their decomposition accordingly.

6. Conclusions

Appendix A Quantifying Zonogon Perimeters

Appendix B The Non-Negativity of Partial f-Information

Appendix B.1. Properties of the Loss Measure on the Synergy Lattice

- 1.

- If , then the implication holds for any since the bottom element is inferior (⊑) to any other channel.

- 2.

- If , then is also a non-empty set since .

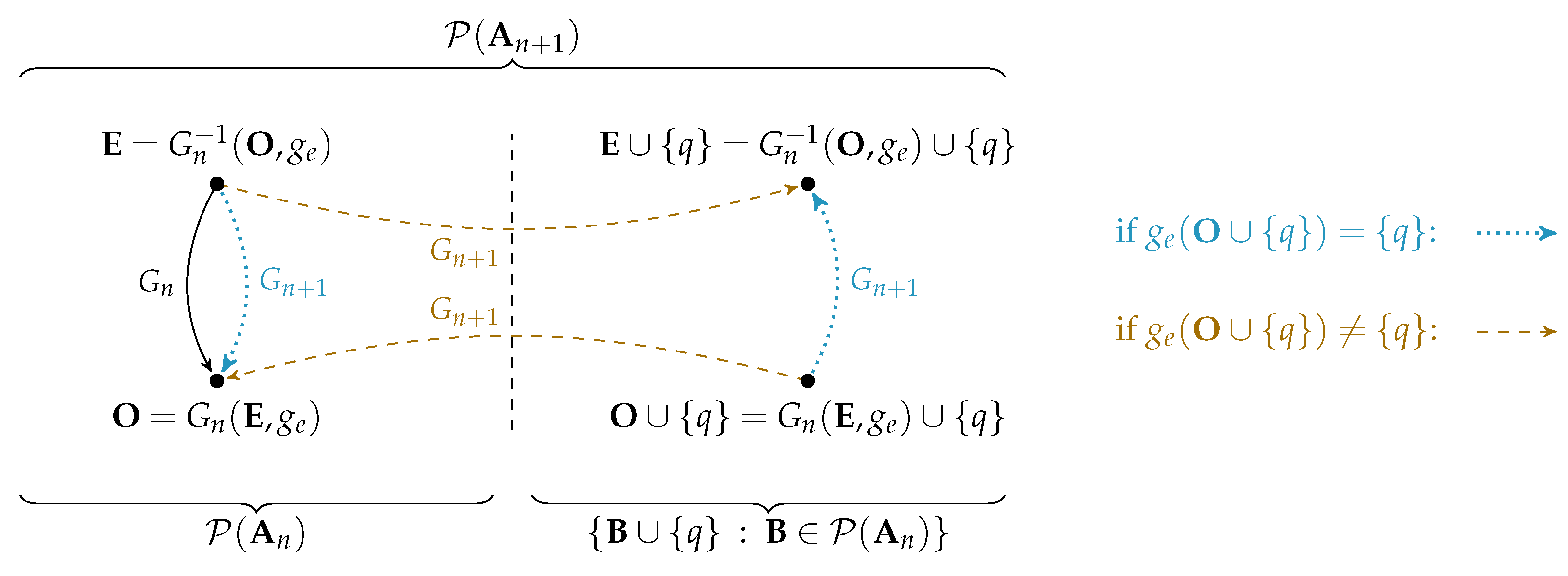

Appendix B.2. Mapping subsets of even and odd cardinality

- a)

- For any subset with even cardinality, the function returns a subset of function :

- b)

- The function which satisfies Equation A8 has an inverse on its first argument .

- 1.

-

At the base case , the sets of subsets are and . We define the function for any to satisfy both required properties:

- a)

- b)

- The function is a bijection from to and therefore has an inverse on its first argument (requirement of Equation A9).

- 2.

- 3.

-

For the induction step, we show the definition of a function that satisfies both required properties. For sets , the subsets of even and odd cardinality can be expanded as shown in Equation A10.We define for and at any as shown in Equation A11 using the function and its inverse from the induction hypothesis. The function is defined for any subset in as it can be seen from Equation A10.Figure A1 provides an intuition for the definition of : the outcome of determines, if the function maintains or breaks the mapping of .The function F as defined in Equation A11 satisfies both requirements (Equation A8 and A9) for any :

- a)

-

To demonstrate that the function satisfies the subset relation of Equation A8, we analyze the four cases for the return value of as defined in Equation A11 individually:

- -

- holds, since the function always returns a subset of its input (Equation A7).

- -

- holds by the induction hypothesis.

- -

- if then : Since the input to function is not the empty set, the function returns a singleton subset of its input (Equation A7). If the element in the singleton subset is unequal to q, then it is a subset of .

- -

- if then holds trivially.

- b)

-

To demonstrate that the function has an inverse (Equation A9), we show that the function is a bijection from to . Since the function is defined for all elements in and both sets have the same cardinality (, Equation A6), it is sufficient to show that the function is distinct for all inputs.The return value of has four cases, two of which return a set containing q (case 1 and 4 in Equation A11), while the two others do not (case 2 and 3 in Equation A11). Therefore, we have to show that both of these cases cannot coincide for any input:

- -

- Case 2 and 3 in Equation A11: If the return value of both cases was equal, then and therefore . This leads to a contradiction, since the condition of case 3 ensures , while the condition of case 2 ensures . Hence, the return values of case 2 and 3 are distinct.

- -

- Case 1 and 4 in Equation A11: If the return value of both cases was equal, then and therefore . This leads to a contradiction, since the condition of case 4 ensures , while the condition of case 1 ensures . Hence, the return values of case 1 and 4 are distinct.

Since the function is a bijection, there exists an inverse .

Appendix B.3. The Non-Negativity of the Decomposition

- 1.

- 2.

-

Let , then its cover set is non-empty (). Additionally, we know that no atom in the cover set is the empty set (), since the empty atom is the top element ().Since it will be required later, note that the inclusion-exclusion principle of a constant is the constant itself as shown in Equation A16 since without the empty set there exists one more subset of odd cardinality than with even cardinality (see Equation A6).We can re-write the Möbious inverse as shown in Equation A17.Consider the non-empty set of channels , then we obtain Equation A18b from Lemma A6.We can construct an upper bound on based on the cover set as shown in Equation A19.By transitivity of Equation A18b and A19d, we obtain Equation A20.By Equation A17 and A20, we obtain the non-negativity of pointwise partial information as shown in Equation A21.

Appendix C Scaling f-Information Does Not Affect Its Transformation

Appendix D Decomposition Example Distributions

| Probability | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | XOR | Unq | PwUnq | RdnErr | Tbc | AND | Generic | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 0 | 3/8 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 0.0625 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.3000 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | - | 1/4 | 1/4 | 1/8 | - | 1/4 | 0.1875 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1/4 | - | - | - | 1/4 | - | 0.1500 |

| 0 | 2 | 1 | - | - | 1/4 | - | - | - | - |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 1/4 | - | - | 1/4 | 0.0375 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1/4 | 1/4 | - | 1/8 | - | - | 0.0500 |

| 1 | 0 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1/4 | - | - |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1/4 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.2125 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1/4 | - | 3/8 | - | 1/4 | - |

| 1 | 1 | 3 | - | - | - | - | 1/4 | - | - |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | - | - | 1/4 | - | - | - | - |

Appendix E The Relation of Total Variation to the Zonogon Height

Appendix F Information Flow Example Parameters and Visualization

References

- Williams, P.L.; Beer, R.D. Nonnegative Decomposition of Multivariate Information. arXiv 2515, arXiv:1004.2515. [Google Scholar]

- Lizier, J.T.; Bertschinger, N.; Jost, J.; Wibral, M. Information Decomposition of Target Effects from Multi-Source Interactions: Perspectives on Previous, Current and Future Work. Entropy 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, V.; Chong, E.K.P.; James, R.G.; Ellison, C.J.; Crutchfield, J.P. Intersection Information Based on Common Randomness. Entropy 2014, 16, 1985–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertschinger, N.; Rauh, J.; Olbrich, E.; Jost, J. Shared Information—New Insights and Problems in Decomposing Information in Complex Systems. Proceedings of the European Conference on Complex Systems 2012; Gilbert, T., Kirkilionis, M., Nicolis, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2013; pp. 251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Harder, M.; Salge, C.; Polani, D. Bivariate measure of redundant information. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 87, 012130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, C. A New Framework for Decomposing Multivariate Information. PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2019.

- Polyanskiy, Y.; Wu, Y. Information theory: From coding to learning. Book draft 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mironov, I. Rényi Differential Privacy. 2017 IEEE 30th Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF), 2017, pp. 263–275. [CrossRef]

- Bertschinger, N.; Rauh, J.; Olbrich, E.; Jost, J.; Ay, N. Quantifying Unique Information. Entropy 2014, 16, 2161–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, V.; Koch, C. Quantifying Synergistic Mutual Information. In Guided Self-Organization: Inception; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; pp. 159–190. [CrossRef]

- Goodwell, A.E.; Kumar, P. Temporal information partitioning: Characterizing synergy, uniqueness, and redundancy in interacting environmental variables. Water Resources Research 2017, 53, 5920–5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.G.; Emenheiser, J.; Crutchfield, J.P. Unique information via dependency constraints. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 2018, 52, 014002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, C.; Lizier, J.T. Pointwise Partial Information Decomposition Using the Specificity and Ambiguity Lattices. Entropy 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ince, R.A.A. Measuring Multivariate Redundant Information with Pointwise Common Change in Surprisal. Entropy 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, F.E.; Mediano, P.A.M.; Rassouli, B.; Barrett, A.B. An operational information decomposition via synergistic disclosure. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 2020, 53, 485001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolchinsky, A. A Novel Approach to the Partial Information Decomposition. Entropy 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertschinger, N.; Rauh, J. The Blackwell relation defines no lattice. 2014 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, 2014, pp. 2479–2483. [CrossRef]

- Lizier, J.T.; Flecker, B.; Williams, P.L. Towards a synergy-based approach to measuring information modification. 2013 IEEE Symposium on Artificial Life (ALife), 2013, pp. 43–51. [CrossRef]

- Knuth, K.H. Lattices and Their Consistent Quantification. Annalen der Physik 2019, 531, 1700370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mages, T.; Rohner, C. Decomposing and Tracing Mutual Information by Quantifying Reachable Decision Regions. Entropy 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, D. Equivalent comparisons of experiments. The annals of mathematical statistics 1953, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyman, J.; Pearson, E.S. IX. On the problem of the most efficient tests of statistical hypotheses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical or Physical Character 1933, 231, 289–337. [Google Scholar]

- Chicharro, D.; Panzeri, S. Synergy and Redundancy in Dual Decompositions of Mutual Information Gain and Information Loss. Entropy 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszár, I. On information-type measure of difference of probability distributions and indirect observations. Studia Sci. Math. Hungar. 1967, 2, 299–318. [Google Scholar]

- Rényi, A. On measures of entropy and information. Proceedings of the Fourth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Volume 1: Contributions to the Theory of Statistics. University of California Press, 1961, Vol. 4, pp. 547–562.

- Sason, I.; Verdú, S. f -Divergence Inequalities. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2016, 62, 5973–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kailath, T. The divergence and Bhattacharyya distance measures in signal selection. IEEE transactions on communication technology 1967, 15, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, E. Channel Polarization: A Method for Constructing Capacity-Achieving Codes for Symmetric Binary-Input Memoryless Channels. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2009, 55, 3051–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A. On a measure of divergence between two statistical populations defined by their probability distribution. Bulletin of the Calcutta Mathematical Society 1943, 35, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Mages, T.; Anastasiadi, E.; Rohner, C. Implementation: PID Blackwell specific information. https://github.com/uu-core/pid-blackwell-specific-information, 2024. Accessed on 15.03.2024.

- Cardenas, A.; Baras, J.; Seamon, K. A framework for the evaluation of intrusion detection systems. 2006 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (S & P’06), 2006, pp. 15 pp.–77. [CrossRef]

- Rauh, J.; Bertschinger, N.; Olbrich, E.; Jost, J. Reconsidering unique information: Towards a multivariate information decomposition. 2014 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, 2014, pp. 2232–2236. [CrossRef]

- Bossomaier, T.; Barnett, L.; Harré, M.; Lizier, J.T. An introduction to transfer entropy. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

| Kullback-Leiber (KL) divergence | ||

| Total Variation (TV) | ||

| -divergence | ||

| Squared Hellinger distance | ||

| Le Cam distance | ||

| Jensen-Shannon divergence | ||

| Hellinger divergence with | ||

| -divergence with |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).