1. Introduction

Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide receptor 1 (PAC1-R) is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that has a higher affinity for pituitary adenylate cyclase- activating polypeptide (PACAP) than for vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP). [

1]. PAC1-R is widely distributed in the central nervous system, and in the adult brain, PAC1-R expression is particularly high in neurogenic regions such as the subventricular zone of the olfactory bulb or the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus [

2]. PACAP's anti-apoptotic effects, induction of neural stem cell differentiation [

3] and antioxidant effects are mediated by PAC1-R [

4]. PACAP inhibits pathological processes in Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD) models through PAC1-R [

5], and thus PAC1-R could be a target for the development of drugs for neurodegenerative diseases.

In a previous study, we used computerized molecular docking to screen Doxycycline and minocycline for docking with PAC1-R. Experiments verified that both had neuroprotective effects and confirmed that Doxycycline was a positive allosteric modulator targeting PAC1-R [

6,

7]. In addition, we obtained new positive allosteric modulators targeting PAC1-R by computerized virtual screening and laboratory screening which was named small positive allosteric modulator 1 (SPAM1) (Patent No.: CN202210388027.7; Molecular Formula: C

20H

19N

3O

4), And SPAM1 targeted PAC1-R with significantly higher affinity than DOX, and SPAM1 had more effective cytoprotective activity [

8]. We showed in our latest study that SPAM1 induces nuclear translocation of PAC1-R, which exerts neuroprotective effects by regulating neuronal restriction silencing factor (NRSF) [

9].

Sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) is a member of the Sirtuin family that promotes dendritic morphogenesis in hippocampal neurons during developmental stages [

10]. SIRT6 is associated with the aging process and has DNA repair [

11] and neuroprotective effects, and severely reduced levels of SIR6 have been observed in patients with Alzheimer's disease [

12]. YinYang 1 (YY1) is a zinc finger protein that belongs to the GLI-Küppel gene family [

13]. The expression level of YY1 increases with age [

14]. Global knockout of YY1 resulted in mouse embryonic death, and mice exhibited motor deficits and cognitive deficits in the YY1 conditional knockout mouse model [

15]. Studies have shown that a decline in LaminB1 levels during the aging process leads to senescence and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease [

16]. Decreased LaminB1 expression levels cause age-dependent decrease in hippocampal neural stem cell activity [

17]. Both p16 and Lamin B1 are recognized as biomarkers of cellular senescence [

18].

In the present study, we demonstrated that SPAM1 up-regulated the expression of SIRT6 and Lamin B1 and down-regulated the expression of YY1 and p16 in the hippocampus of D-gal-induced aging model mice. In this study, we combined whole transcriptome sequencing and proteomic analysis to further investigate the mechanism by which SPAM1 exerts neuroprotective effects, thereby laying the pharmacological foundation for SPAM1 as a therapeutic agent for neurodegenerative diseases.

3. Discussion

GPCRs can regulate gene transcription through an unconventional mode of signal transduction, whereby the GPCR cleaves and relies on its carboxyl-terminal structural domain to translocate to the nucleus [

20]. We demonstrated in a previous study that PAC1-R also has such a transduction pattern [

9,

21,

22]. PAC1-R has a high affinity for PACAP due to a specific region of its N-terminal extracellular domain 1 (EC1) domain [

1]. Because of its crucial role in the nervous system, PAC1-R has become a target for drugs [

23]. In previous studies, we targeted PAC1-R-EC1 to screen doxycycline, minocycline, and SPAM1 in a previous study, and subsequent experiments demonstrated that SPAM1 had more significant neuroprotective activity [

6,

7,

8]; nevertheless, little is known about the mechanism of action of SPAM1.

D-gal was used to induce a simulated aging model in mice [

24]. DG plays a key role in hippocampal memory formation, and when DG lesions impair many hippocampus-dependent memory functions [

25]. Accumulation of p16 occurs in senescent cells, and downregulation of Lamin BI is another important feature of cellular senescence [

18]. SIRT6 is implicated in DNA repair, and mice knocked down for SIRT6 show a degenerative phenomenon similar to aging [

26]. The new findings also suggest that the changes observed in SIRT6-deficient brains also occur in the aging human brain, particularly in patients with Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Huntington's, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. SIRT6 is a key regulator of mitochondrial function in the brain and interacts with the transcription factor YY1 to jointly influence mitochondrial function [

27]. It is accompanied by a decrease in SIRT6 levels and an increase in YY1 levels in aged mice [

14]. Data from clinical studies indicate that plasma levels of YY1 are significantly elevated in patients with major depressive disorder [

28]. Notably, we showed in a previous study by chromatin immunoprecipitation that YY1 may be recruited by the nuclear translocated PAC1-R [

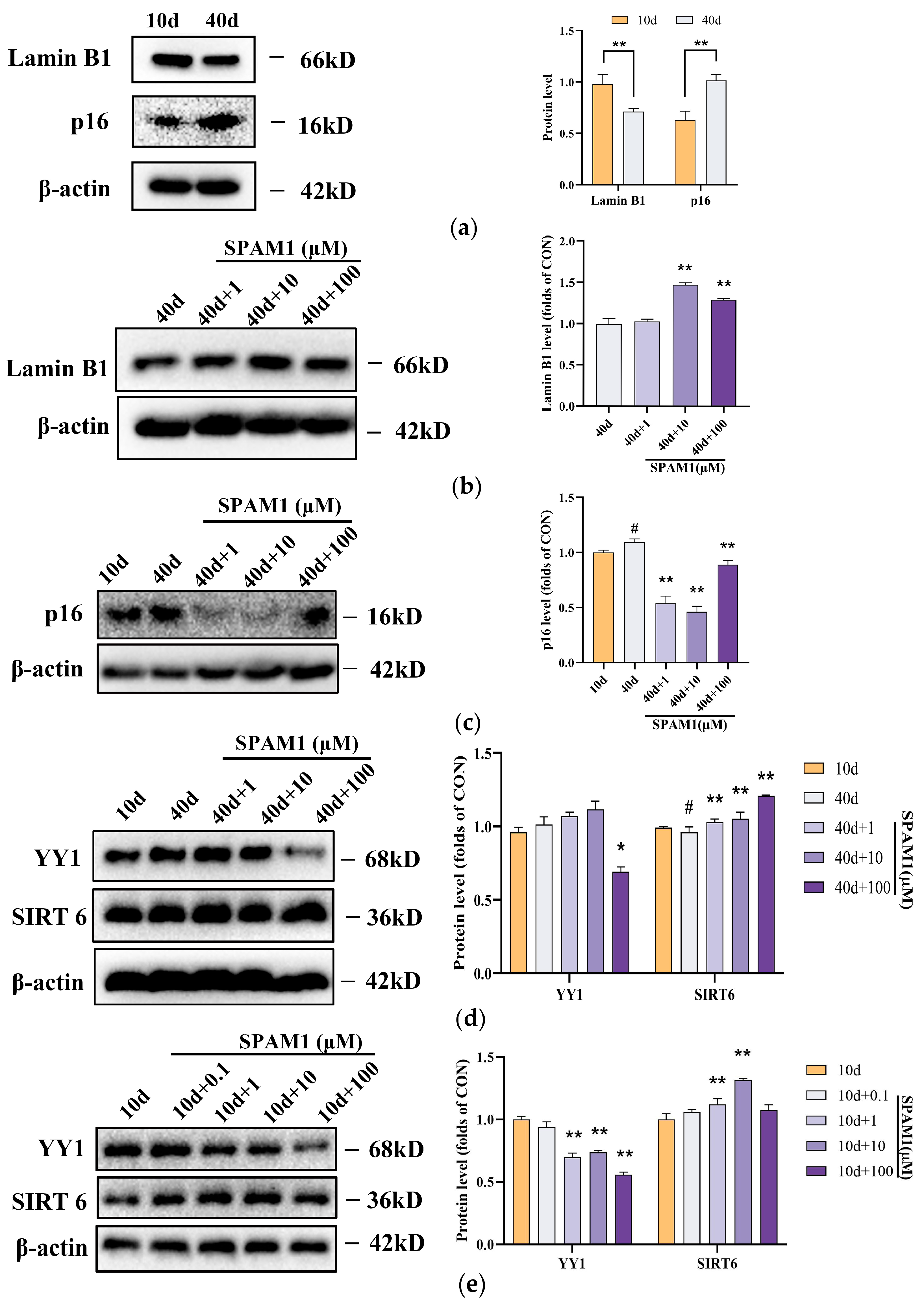

21]. In this study, we showed that compared with mice in the NOR group, the number of D-gal-induced DG neurons in the hippocampus of the brain was reduced and structural alterations were observed in the D-gal-induced senescent mouse model, which was accompanied by the down-regulation of the expression levels of SIRT6 and Lamin B1 in the DG, as well as the up-regulation of the expression levels of YY1 and p16. However, mice treated with different concentrations of SPAM1 showed an increase in the number of DG neurons, structural recovery, and reversal of the expression of the four proteins in the appeal, that is, up-regulation of SIRT6 and Lamin B1, and down-regulation of YY1 and p16. This suggests that SPAM1 plays a role in the maintenance of the structure of the hippocampus and in some of the protein expression levels, in other words, our results further support that SPAM1 has neuroprotective effects and treats neurodegenerative disorders. protective effects and therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative diseases. While at the cellular level, the same exploration was carried out in this study using RGC-5 cells and it was found that upregulation of p16 and downregulation of Lamin B1 accompanied in 40-day senescent RGC-5 cells compared to 10-day senescent RGC-5 cells, but the expression level of p16 was reduced and the level of Lamin B1 was elevated after the use of SPAM1. We likewise carried out the exploration of its mechanism and found that SPAM1 down-regulated the expression of YY1 and up-regulated the expression of SIRT6. Notably, such results were also presented in unsenescent 10-day-old RGC-5 cells, suggesting that this mechanism is also useful in normal neuronal cells. These results suggest that SPAM1 can exert anti-aging effects not only in senescent neuronal cells, but also in normal neuronal cells, and in corroboration with this, the present study found that the KEGG pathway involved in SPAM1 in transcriptomics includes the longevity regulating pathway.

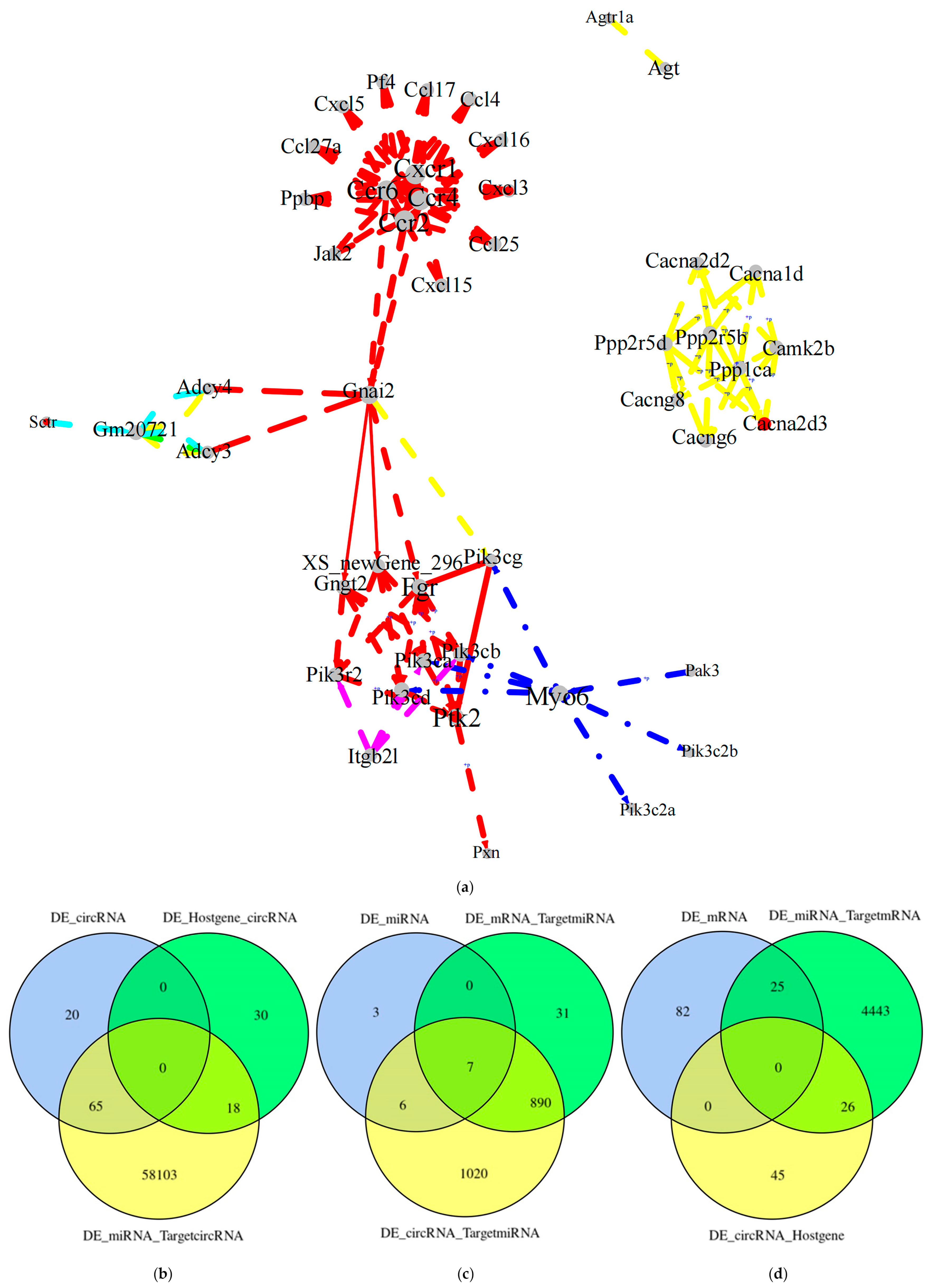

The KEGG pathway of differentially expressed RNAs has also provided many new insights into the mechanism of SPAM1 action. For example, the brain renin-angiotensin system has been implicated in Alzheimer's disease neuropathology [

29], and it may serve as a novel potential therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease [

30]. It has been shown that the phospholipase D signaling pathway is a key signaling pathway in Alzheimer's disease [

31], and PACAP activates PAC1, and PAC1 is coupled to the phospholipase D signaling pathway to trigger downstream effects [

32]. Differentially expressed mRNAs were enriched for neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction in addition to the two pathways described above. It has also been shown that PACAP has an important role in the olfactory system through PAC1-R [

33]. PACAP is also involved in the regulation of circadian entrainment to light [

34,

35]. Differentially expressed LncRNA target genes were enriched in were enriched in the above two pathways in addition to the longevity regulating pathway − multiple species, longevity regulating pathway Cell cycle, etc. Interestingly, SIRT6 is also involved in the regulation of longevity [

36]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system is involved in regulating synaptic plasticity and memory formation [

37], and its dysfunction has been linked to Alzheimer's disease and dementia [

38]. The PACAP/PKA pathway plays a role in tumor therapy by regulating the Hedgehog signaling pathway [

39,

40]. In addition to these two pathways, Host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs is also enriched in synaptic vesicle cycle, cGMP-PKG signaling pathway, cAMP signaling pathway, etc., and are also enriched in the circadian rhythm as are differentially expressed LncRNA target genes. Similarly, differentially expressed miRNA target genes were enriched in protein digestion and absorption and cAMP signaling pathway, in addition to Calcium signaling pathway.

Barrier-to-autointegration factor is a small DNA-binding protein [

41] that plays a role in repairing DNA double-strand breaks [

42] and repairing nuclear ruptures [

43]. Mutations in it also cause premature aging syndrome [

44]. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II is the most abundant protein in excitatory synapses and is central to synaptic plasticity, learning and memory [

45]. Neurofilaments play an important role in axon radial growth and nerve conduction [

46]. PACAP was able to stimulate size-sieved stem cells to differentiate into neurons, a process accompanied by increased expression of the neurofilament light polypeptide [

47]. Furthermore, PACAP induced the differentiation of serum-cultured SH-SY5Y cells into neuroblastic cell, a process accompanied by an increase in the mRNA levels of three neurofilament proteins [

48]. This suggests that PACAP could be used for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which is also the case [

49,

50,

51,

52]. In the present study, we have formally demonstrated that SPAM1 can up-regulate the expression of three types of neurofilaments at the proteomic level, and we have shown that SPAM1 has also been shown to up-regulate the expression of PACAP and PAC1-R, which suggests that SPAM1 may be useful in the treatment of ALS. It has been demonstrated that Apolipoprotein D is upregulated at the mRNA and protein levels after the action of PACAP [

53]. Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 4 is expressed in the hippocampus, promotes neurite extension in hippocampal neurons, and is involved in neuronal and glial cell differentiation [

54]. In the present study, proteome sequencing showed that after the action of SPAM1, barrier-to-autointegration factor, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II subunit alpha, calcium/ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II subunit beta, neurofilament light polypeptide, neurofilament medium polypeptide, neurofilament heavy polypeptide, apolipoprotein D and leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 4 expression were increased. These aforementioned proteins that have been validated to be associated with PACAP or to play a role in the nervous system were confirmed to have increased expression in the proteome sequencing of this study.

Differentially expressed proteins were enriched to the Neurotrophin signaling pathway, which is consistent with our previous experimental data in RGC-5 cells [

9]. Differently expressed proteins are also enriched for circadian entrainment and olfactory transduction, as are differentially expressed RNAs. PACAP was shown to regulate GnRH signaling [

55], and differential proteins were also enriched for this pathway in this study.

Whole transcriptome and proteome sequencing results confirmed that SPAM1 exerts its biological functions through known signaling pathways such as cAMP signaling pathway and calmodulin pathway, and also suggested that SPAM1 also exerts its neuroprotective and anti-aging effects through other pathways, which helps to add to our further explorations of the mechanism of action of SPAM1.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Cell Lines

Mouse retinal ganglion cell (RGC-5) lines were provided by the Chinese Academy of Life Sciences (Shanghai, China). Peptide SPAM1 was synthesized by GL Biochem Ltd. (Shanghai, China) at 95% purity. The purity of the peptides was confirmed by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and they were characterized using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry.

4.2. Grouping and Treatment of Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (6 weeks old), purchased from Guangzhou Red Carrot Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Mice were allowed to eat and drink freely in a clean environment with 12 h of light, 24 °C ± 1 °C and 55 ± 5% humidity. The mice were randomly divided into 6 groups. After 10 days of acclimatization to the new environment, the mice were continuously medicated for 6 weeks with two injections per day. The first was an injection of D-galactose (D-gal) (150 mg/kg/day) or saline; SPAM1 or saline was injected 5 min after the first injection. Both injections were intraperitoneal; the first injection was in the left peritoneal cavity and the second in the right. The mice were grouped as follows: (1) normal control group (NOR): saline without D-gal; (2) D-gal group: D-gal + saline; (3) 0.1µmol/kg/day SMAP1 group: D-gal + 0.1µmol/kg/day SMAP1; (4) 1µmol/kg/day SMAP1 group: D-gal + 1µmol/kg/day SMAP1; (5) 10µmol/kg/day SMAP1 group: D-gal + 1µmol/kg/day SMAP1; (6) 100µmol/kg /day SMAP1 group: D-gal + 100µmol/kg/day SMAP1.

4.3. Tissue Preparation

After completion of dosing on day 42, mice were euthanized, weighed, and the brains were quickly removed, washed with RNase free water, some brain tissue was placed in 4 % paraformaldehyde solution, followed by paraffin embedding. And the remaining tissue was immediately put into liquid nitrogen and subsequently transferred to -80°C for storage.

4.4. Hematoxylin-Eosin Staining (HE) Staining

Paraffin sections were placed in dewaxing solution and different concentrations of ethanol, stained with hematoxylin stain for 3-5 minutes, eosin stain for 5 minutes, ethanol and xylene were used for dehydration, and the sections were sealed with neutral gum.

4.5. Senescence-Associated-β-Galactosidase Staining

The RGC-5 cells were plated and cultured for some time in six-well plates. When the cells reached the confluence rate of 80%, the experimental groups were subjected to treatment of SPAM1 (1µM-100µM) for 24 hours. The same volume fetal bovine serum-free basal medium used for the control group was treated without any treatment. The cell culture medium was aspirated, washed once with PBS, and then fixed and stained according to the instructions of the cell senescence β-galactosidase staining kit (Beyotime, shanghai, Chian). After incubation overnight at 37°C, the percentage of stained senescent cells was obtained by observing and counting under an ordinary light microscope. All experiments were performed in at least three parallel replicates and repeated three times.

4.6. Western Blotting Assays

RGC-5 cells in logarithmic growth phase were inoculated into 6-well culture plates with 2 × 105 cells per well and cultured in F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum at 37◦ C, 5% CO2, and 80% fusion. The experimental group was treated with SPAM1 (1-100 µM) for 40 days (or 10 days). The control group was treated with fetal bovine serum-free basal medium. Total protein was extracted from the cells using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate,1% SDS, and protease inhibitors (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) on ice for 30 min and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The membranes were co-incubated with the following polyclonal antibodies: anti-SIRT6 antibody (12486S; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-YY1 antibody (sc-7341; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Lamin B1 Polyclonal antibody (12987-1-AP; Proteintech), anti-P16 antibody (AB51243; abcam), anti-NEFL antibody (2837T; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-NEFM antibody (67255S; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-β-actin antibody (EM21002, HUABIO). It was then incubated with HRP-coupled secondary antibody (HA1006, HUABIO; ab150075, abcam). Protein bands were displayed using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Beyotime Biotech). All experiments were performed in at least three parallel replicates and repeated three times.

4.7. Immunohistochemistry

The paraffin sections were put into dewaxing solution and different concentrations of ethanol, antigen repairing solution was used for antigen repairing, serum or BSA was used for sealing, SIRT6 was detected by SIRT6 Polyclonal antibody (13572-1-AP; Proteintech), YY1 was detected by anti-YY1 antibody (sc-7341; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Lamin B1 was detected by Lamin B1 Polyclonal antibody (12987-1-AP; Proteintech), and P16 was detected by anti-P16 antibody(sc-1661; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and the corresponding secondary antibody was added, the color was developed by diaminobenzidine, the nuclei of the cells were restained by hematoxylin, the cells were dehydrated with ethanol, n-butyl alcohol, and xylene, and the slices were sealed by sealer adhesive.

4.8. Whole Transcriptome Sequencing

3 samples were randomly selected from the D-gal group (subsequently named DA group) and 3 samples were randomly selected from the 100 µmol/kg/day SMAP1 group (subsequently named SP group). 6 mouse brain tissue samples were subjected to total RNA extraction by Genepioneer Biotechnologies Ltd. (Nanjing, China) and sequenced by Illumina Nova 6000 platform and NovaSeq 2500 platform after the libraries were tested and approved. Nova 6000 platform and Illumina NovaSeq 2500 platform for sequencing. Raw sequencing data were filtered with fastp (

https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp) (accessed on 28 August 2023) and Cutadapt (v2.10) [

56] to obtain high-quality Clean Data.Clean reads were compared to the Mus musculus genome (

http://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/current_fasta/mus_musculus/) (accessed on 29 August 2023) using HISAT2 [

57] and Bowtie (v1.2.2) (

http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml) (accessed on 29 August 2023). Differentially expressed RNAs were functionally annotated and enriched using the Gene Ontology (GO) database (

http://www.geeontology.org) (accessed on 29 August 2023) and the KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) database (

http://www.kegg.jp) (accessed on 29 August 2023).

4.9. Proteomic Analysis

3 samples each from D-gal group (subsequently named DA group) and 100µmol/kg /day SMAP1 group (subsequently named SP group) were randomly selected. 6 mouse brain tissue samples were handed over to Genepioneer Biotechnologies Ltd. (Nanjing, China) for protein extraction and quantification, and TMT proteome assay was completed. The Mus musculus database (

http://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-106/fasta/mus_musculus/) (accessed on 9 August 2023) was searched for mass spectrometry downstream data using Proteome Discovery software, and spectral peptides and proteins were quantified. Protein functional annotation was performed using BLAST software (version: 2.2.26) (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) (accessed on 9 August 2023). Interaction analysis of identified proteins was performed using StringDB protein interaction database (

http://string-db.org/) (accessed on 9 August 2023), Gene Ontology (GO) database (

http://www.geeontology.org) (accessed on 9 August 2023) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) database (

http://www.kegg.jp) (accessed on 9 August 2023) for functional annotation and enrichment analysis of differentially expressed proteins.

4.10. Statistical Analyses

GraphPad Prism 8 was used for statistical analysis. All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences between groups. When P < 0.05, the difference was statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study confirmed that SPAM1 was able to restore the structure and neuron number of the brain hippocampus and resisted the senescence of RGC-5 cells. SPAM1 also up-regulated and D-gal senescence mouse model hippocampus expression of SIRT6 and Lamin B1, and down-regulated the expression of YY1 and p16, and this result was also confirmed in RGC-5 cells.

In the present study, we also combined whole transcriptome analysis and proteome analysis to further investigate the mechanism of SPAM1 action. The results of whole transcriptome and proteome analyses suggested that SPAM1 acts through neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, longevity regulating pathway - multiple species, longevity regulating pathway, and other mechanisms. regulating pathway, cell cycle and other pathways.

We have demonstrated that SPAM1 up-regulates PACAP and PAC-1R expression [

9], and the results of whole transcriptome and proteome analyses indicate that SPAM1 is indeed associated with the PACAP-PAC1-R pathway, e.g., SPAM1 is expressed through the cAMP signaling pathway, calcium signaling pathway, and neurotrophin signaling pathway.

It is confirmed that SPAM1 regulates PAC1-R through positive allosteric regulation and exerts neuroprotective effects both through the PACAP-PAC1-R pathway and through a pathway that is different from PACAP.

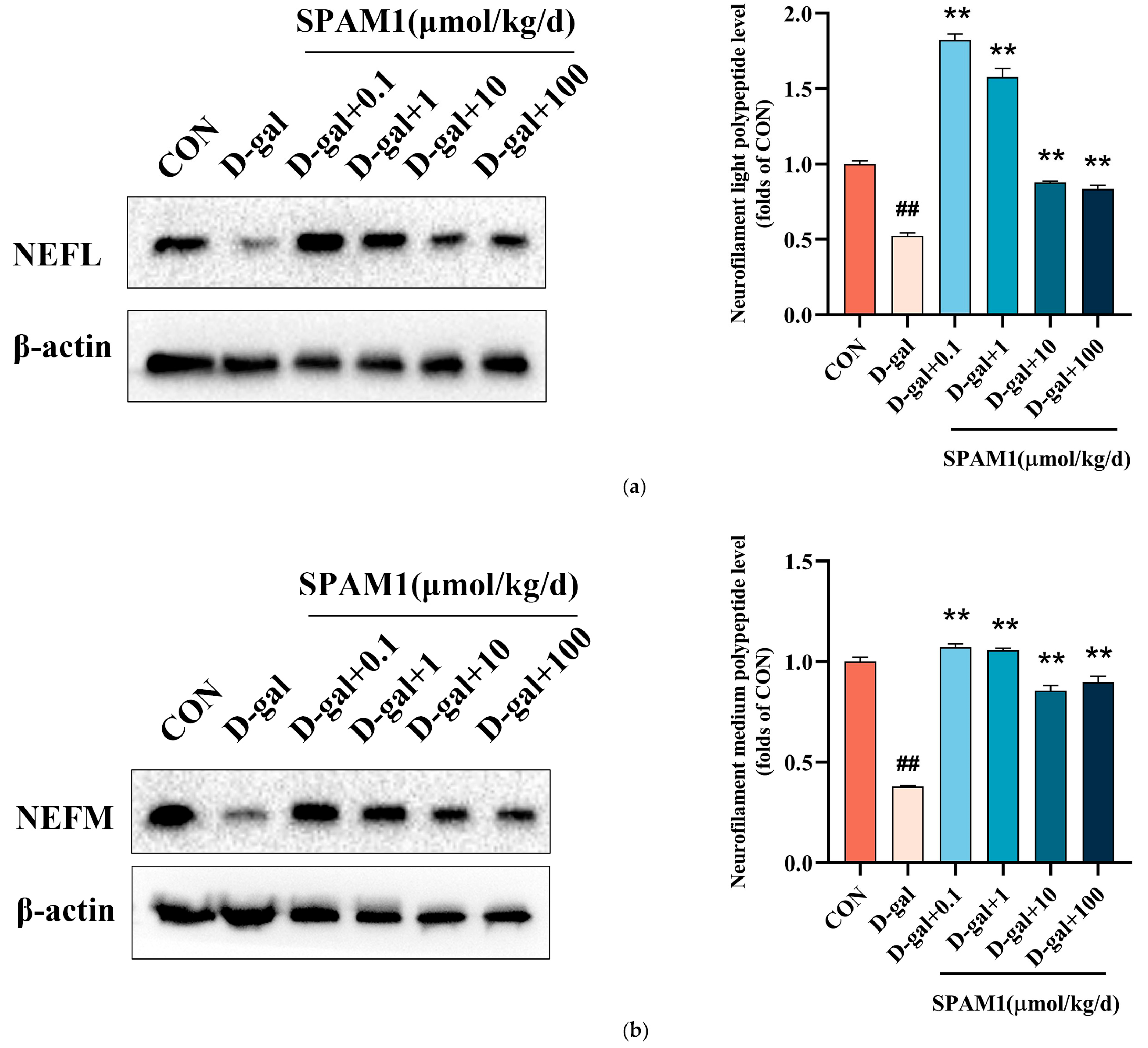

Furthermore, proteomics results showed that SPAM1 up-regulated the expression of neurofilament light polypeptide, neurofilament medium polypeptide, neurofilament heavy polypeptide and peripherin. In this study, western blot verified that SPAM1 could up-regulate the expression of neurofilament light polypeptide and neurofilament medium polypeptide, suggesting that SPAM1 could play a neuroprotective role by repairing neuronal structure.

Figure 1.

SPAM1 attenuates D-gal-induced reduction in the number of mouse hippocampal neurons. HE staining showed that D-gal treatment led to a reduction in mouse hippocampal neurons, which was most significantly reversed by SPAM1 at concentrations of 0.1μmol/kg/day and 100μmol/kg/day. Data are presented as the mean ± SE, n = 8-10.

Figure 1.

SPAM1 attenuates D-gal-induced reduction in the number of mouse hippocampal neurons. HE staining showed that D-gal treatment led to a reduction in mouse hippocampal neurons, which was most significantly reversed by SPAM1 at concentrations of 0.1μmol/kg/day and 100μmol/kg/day. Data are presented as the mean ± SE, n = 8-10.

Figure 2.

SPAM1 ameliorated RGC cells senescence. (a) β-gal staining and (b) corresponding statistics showed that the number of β-gal-positive RGC-5 cells was significantly reduced after the action of different concentrations of SPAM1. **, P<0.01, vs. 40d. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three experiments.

Figure 2.

SPAM1 ameliorated RGC cells senescence. (a) β-gal staining and (b) corresponding statistics showed that the number of β-gal-positive RGC-5 cells was significantly reduced after the action of different concentrations of SPAM1. **, P<0.01, vs. 40d. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three experiments.

Figure 3.

Effect of SPAM1 on the expression levels of SIRT6, YY1, Lamin B1 and p16 in RGC-5 cells. (a)WB images of Lamin B1 and p16 in RGC-5 whole cells (left) and the corresponding statistics (right) show that the expression level of Lamin B1 was reduced and p16 expression was increased in RGC-5 cells at 40 days. **, P<0.01, vs. 10d. (b) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of Lamin B1 in RGC-5 whole cells at 40day show that 10~100μM concentration of SPAM1 significantly increased the expression of Lamin B1. **, P<0.01, vs. 40d. (c) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of p16 in RGC-5 whole cells. The images showed that different concentrations of SPAM1 could down-regulate the expression of p16. #, P<0.05, vs. 10d; **, P<0.01, vs. 40d. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three experiments. (d) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of YY1 and SIRT6 in RGC-5 whole cells showed that 100uM concentration of SPAM1 decreased the expression of YY1 and 1 to 100μM of SPAM1 upregulated the expression of SIRT6. **, P<0.01, vs. 40d. (e) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of YY1 and SIRT6 in RGC-5 whole cells (10days) showed that 100uM concentration of SPAM1 decreased the expression of YY1. **, P<0.01, vs. 10d.

Figure 3.

Effect of SPAM1 on the expression levels of SIRT6, YY1, Lamin B1 and p16 in RGC-5 cells. (a)WB images of Lamin B1 and p16 in RGC-5 whole cells (left) and the corresponding statistics (right) show that the expression level of Lamin B1 was reduced and p16 expression was increased in RGC-5 cells at 40 days. **, P<0.01, vs. 10d. (b) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of Lamin B1 in RGC-5 whole cells at 40day show that 10~100μM concentration of SPAM1 significantly increased the expression of Lamin B1. **, P<0.01, vs. 40d. (c) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of p16 in RGC-5 whole cells. The images showed that different concentrations of SPAM1 could down-regulate the expression of p16. #, P<0.05, vs. 10d; **, P<0.01, vs. 40d. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three experiments. (d) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of YY1 and SIRT6 in RGC-5 whole cells showed that 100uM concentration of SPAM1 decreased the expression of YY1 and 1 to 100μM of SPAM1 upregulated the expression of SIRT6. **, P<0.01, vs. 40d. (e) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of YY1 and SIRT6 in RGC-5 whole cells (10days) showed that 100uM concentration of SPAM1 decreased the expression of YY1. **, P<0.01, vs. 10d.

Figure 4.

Effect of SMAP1 treatment on the expression levels of SIRT6. (a) Immunohistochemical images of SIRT6 expression in the hippocampus (left) and corresponding statistical chart (right) of SIRT6 expression in the hippocampus. (b) Immunohistochemical images of SIRT6 expression in the hippocampus (left) and corresponding statistical chart (right) of Lamin B1 expression in the hippocampus. (c) Immunohistochemical images of SIRT6 expression in the hippocampus (left) and corresponding statistical chart (right) of p16 expression in the hippocampus. (d) Immunohistochemical images of SIRT6 expression in the hippocampus (left) and corresponding statistical chart (right) of p16 expression in the hippocampus. The data for the statistics graph is taken from the red + places in the graph above. #, P<0.05, vs. NOR; ##, P<0.01, vs. NOR; *, P<0.05, vs. saline; **, P<0.01, vs. saline. Data are presented as the mean ± SE, n = 8-10.

Figure 4.

Effect of SMAP1 treatment on the expression levels of SIRT6. (a) Immunohistochemical images of SIRT6 expression in the hippocampus (left) and corresponding statistical chart (right) of SIRT6 expression in the hippocampus. (b) Immunohistochemical images of SIRT6 expression in the hippocampus (left) and corresponding statistical chart (right) of Lamin B1 expression in the hippocampus. (c) Immunohistochemical images of SIRT6 expression in the hippocampus (left) and corresponding statistical chart (right) of p16 expression in the hippocampus. (d) Immunohistochemical images of SIRT6 expression in the hippocampus (left) and corresponding statistical chart (right) of p16 expression in the hippocampus. The data for the statistics graph is taken from the red + places in the graph above. #, P<0.05, vs. NOR; ##, P<0.01, vs. NOR; *, P<0.05, vs. saline; **, P<0.01, vs. saline. Data are presented as the mean ± SE, n = 8-10.

Figure 5.

Heatmaps of differential mRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs and miRNAs in DA and SP groups. (a) Heatmap of differentially expressed mRNAs; (b) Heatmap of differentially expressed lncRNAs; (c) Heatmap of differentially expressed circRNAs; (d) Heatmap of differentially expressed miRNAs.

Figure 5.

Heatmaps of differential mRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs and miRNAs in DA and SP groups. (a) Heatmap of differentially expressed mRNAs; (b) Heatmap of differentially expressed lncRNAs; (c) Heatmap of differentially expressed circRNAs; (d) Heatmap of differentially expressed miRNAs.

Figure 6.

Volcano plots of differential mRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs and miRNAs in DA and SP groups. (a) Volcano plot of 107 differentially expressed mRNAs; (b) Volcano plot of 44 differentially expressed lncRNAs; (c) Volcano plot of 85 differentially expressed circRNAs; (d) Volcano plot of 16 differentially expressed miRNAs.

Figure 6.

Volcano plots of differential mRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs and miRNAs in DA and SP groups. (a) Volcano plot of 107 differentially expressed mRNAs; (b) Volcano plot of 44 differentially expressed lncRNAs; (c) Volcano plot of 85 differentially expressed circRNAs; (d) Volcano plot of 16 differentially expressed miRNAs.

Figure 7.

GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs, differentially expressed LncRNA target genes, host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs and differentially expressed miRNA target genes. (a) GO biological functional analyses of differentially expressed mRNAs; (b) GO biological functional analyses of differentially expressed LncRNA target genes; (c) GO biological functional analyses of host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs; (d) GO biological functional analyses of differentially expressed miRNA target genes.

Figure 7.

GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs, differentially expressed LncRNA target genes, host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs and differentially expressed miRNA target genes. (a) GO biological functional analyses of differentially expressed mRNAs; (b) GO biological functional analyses of differentially expressed LncRNA target genes; (c) GO biological functional analyses of host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs; (d) GO biological functional analyses of differentially expressed miRNA target genes.

Figure 8.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs, differentially expressed LncRNA target genes, host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs and differentially expressed miRNA target genes. (a) KEGG pathway analyses of differentially expressed mRNAs; (b) KEGG pathway analyses of differentially expressed LncRNA target genes; (c) KEGG pathway analyses of host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs; (d) KEGG pathway analyses of differentially expressed miRNA target genes.

Figure 8.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs, differentially expressed LncRNA target genes, host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs and differentially expressed miRNA target genes. (a) KEGG pathway analyses of differentially expressed mRNAs; (b) KEGG pathway analyses of differentially expressed LncRNA target genes; (c) KEGG pathway analyses of host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs; (d) KEGG pathway analyses of differentially expressed miRNA target genes.

Figure 9.

Whole transcriptome association analysis. (a) KEGG integrated pathway network. Each dot represents a gene, each rectangle represents a pathway, and lines represent relationships between genes and genes or other pathways in the pathway. The colors of the different lines represent relationships from different pathways. The red dots are key genes. Combined analysis of differential RNA targeting relationships. (b) Host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs and the associated target RNAs were analyzed; (c)Analysis of target RNAs associated with differentially expressed miRNAs; (d)Analysis of target RNAs associated with differentially expressed mRNAs. DE_circRNA: differentially expressed circRNAs; DE_Hostgene_circRNA: all circRNAs with differentially expressed genes as the host gene; DE_miRNA_TargetcircRNA: all circRNAs targeted by differentially expressed miRNAs; DE_miRNA: differentially expressed miRNAs; DE _mRNA_TargetmiRNA: all miRNAs targeted by differentially expressed mRNA; DE_circRNA_TargetmiRNA: all miRNAs targeted by differentially expressed circRNAs; DE_mRNA: differentially expressed mRNAs; DE_miRNA_TargetmRNA: all target genes of differentially expressed miRNAs; DE_circRNA_Hostgene: differential expression of circRNAs for all host gene.

Figure 9.

Whole transcriptome association analysis. (a) KEGG integrated pathway network. Each dot represents a gene, each rectangle represents a pathway, and lines represent relationships between genes and genes or other pathways in the pathway. The colors of the different lines represent relationships from different pathways. The red dots are key genes. Combined analysis of differential RNA targeting relationships. (b) Host gene that differentially expresses circRNAs and the associated target RNAs were analyzed; (c)Analysis of target RNAs associated with differentially expressed miRNAs; (d)Analysis of target RNAs associated with differentially expressed mRNAs. DE_circRNA: differentially expressed circRNAs; DE_Hostgene_circRNA: all circRNAs with differentially expressed genes as the host gene; DE_miRNA_TargetcircRNA: all circRNAs targeted by differentially expressed miRNAs; DE_miRNA: differentially expressed miRNAs; DE _mRNA_TargetmiRNA: all miRNAs targeted by differentially expressed mRNA; DE_circRNA_TargetmiRNA: all miRNAs targeted by differentially expressed circRNAs; DE_mRNA: differentially expressed mRNAs; DE_miRNA_TargetmRNA: all target genes of differentially expressed miRNAs; DE_circRNA_Hostgene: differential expression of circRNAs for all host gene.

Figure 10.

Heatmaps and volcano plots of differentially expressed proteins in DA and SP groups. (a) Heatmap of differentially expressed proteins; (b) Volcano plot of differentially expressed proteins. (c)Differentially expressed protein string network graph. Each node represents a protein, with thicker lines representing higher association confidence.

Figure 10.

Heatmaps and volcano plots of differentially expressed proteins in DA and SP groups. (a) Heatmap of differentially expressed proteins; (b) Volcano plot of differentially expressed proteins. (c)Differentially expressed protein string network graph. Each node represents a protein, with thicker lines representing higher association confidence.

Figure 11.

GO enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed proteins. (a) GO biological functional analyses of differentially expressed proteins; (b) KEGG pathway analyses of differentially expressed proteins.

Figure 11.

GO enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed proteins. (a) GO biological functional analyses of differentially expressed proteins; (b) KEGG pathway analyses of differentially expressed proteins.

Figure 12.

(a) Spearman correlation heatmap. The columns represent differential proteins and the rows represent differential genes, and the magnitude of the correlation is shown by the difference in color. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. (b) Network diagram. The rectangles in the diagram are differential genes, the circles are differential proteins, the blue lines indicate negative correlations, and the red lines indicate positive correlations.

Figure 12.

(a) Spearman correlation heatmap. The columns represent differential proteins and the rows represent differential genes, and the magnitude of the correlation is shown by the difference in color. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. (b) Network diagram. The rectangles in the diagram are differential genes, the circles are differential proteins, the blue lines indicate negative correlations, and the red lines indicate positive correlations.

Figure 13.

Validation of differentially expressed proteins. (a) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of neurofilament light polypeptide (NEFL) in D-gal model mouse brain tissue showed that significant up-regulation of neurofilament light polypeptide (NEFL) expression at different concentrations of SPAM1. (b) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of neurofilament medium polypeptide (NEFM) in D-gal model mouse brain tissue showed that significant up-regulation of neurofilament medium polypeptide (NEFM) expression at different concentrations of SPAM1. ##, P<0.01, vs. CON; **, P<0.01, vs. D-gal. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three experiments.

Figure 13.

Validation of differentially expressed proteins. (a) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of neurofilament light polypeptide (NEFL) in D-gal model mouse brain tissue showed that significant up-regulation of neurofilament light polypeptide (NEFL) expression at different concentrations of SPAM1. (b) WB images (left) and corresponding statistics (right) of neurofilament medium polypeptide (NEFM) in D-gal model mouse brain tissue showed that significant up-regulation of neurofilament medium polypeptide (NEFM) expression at different concentrations of SPAM1. ##, P<0.01, vs. CON; **, P<0.01, vs. D-gal. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three experiments.