Submitted:

01 March 2024

Posted:

05 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phenotyping

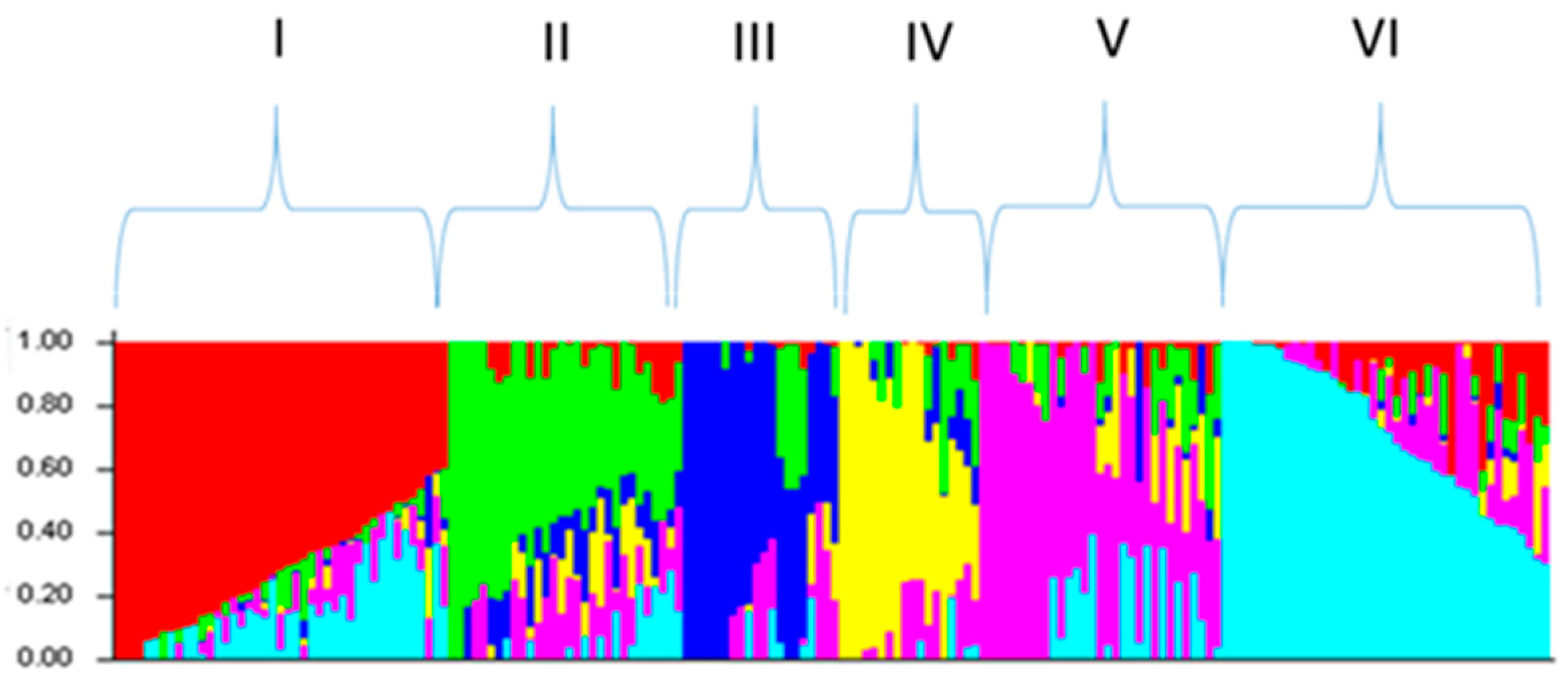

2.2. Analysis of Genotyping Data

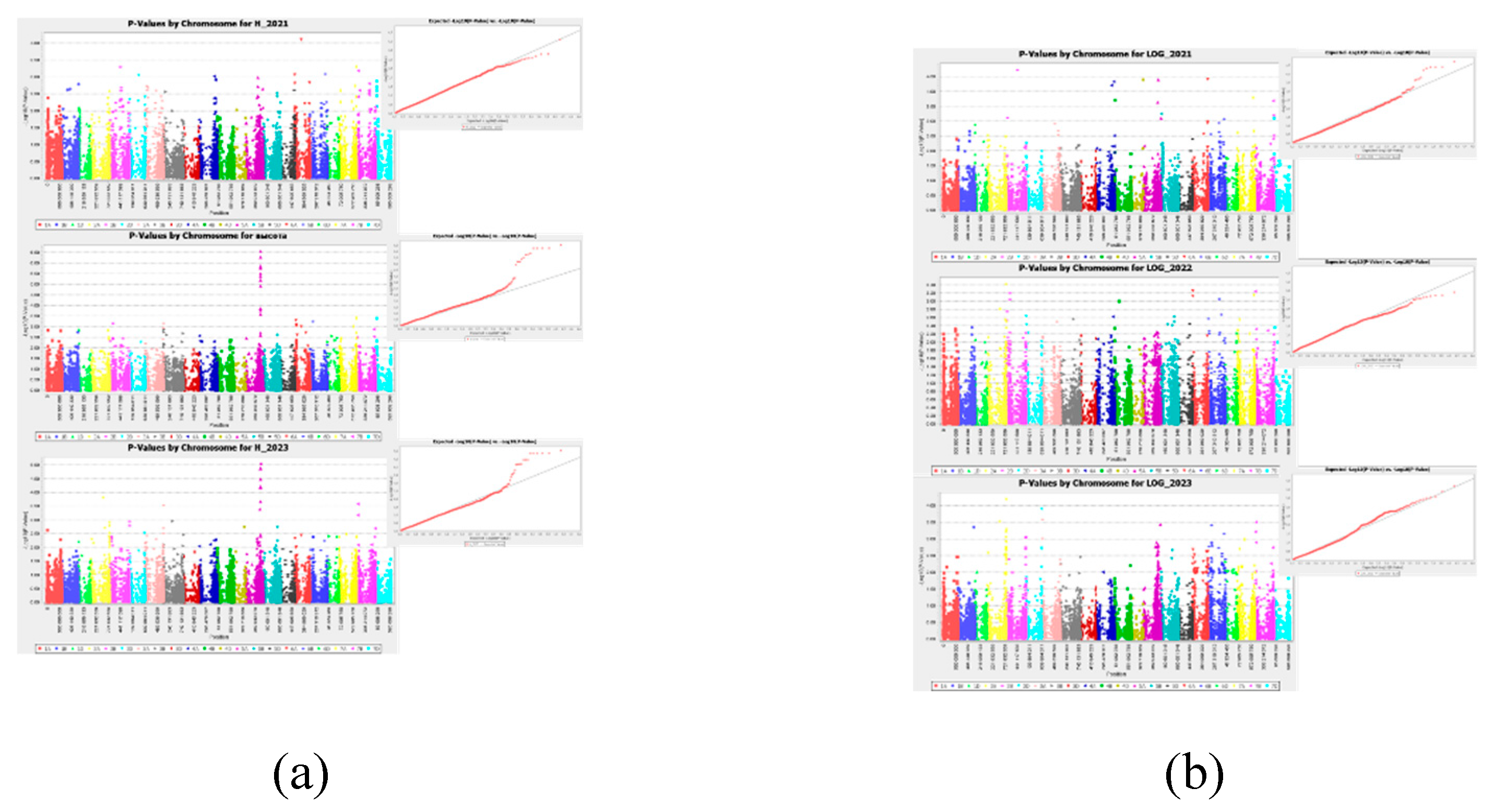

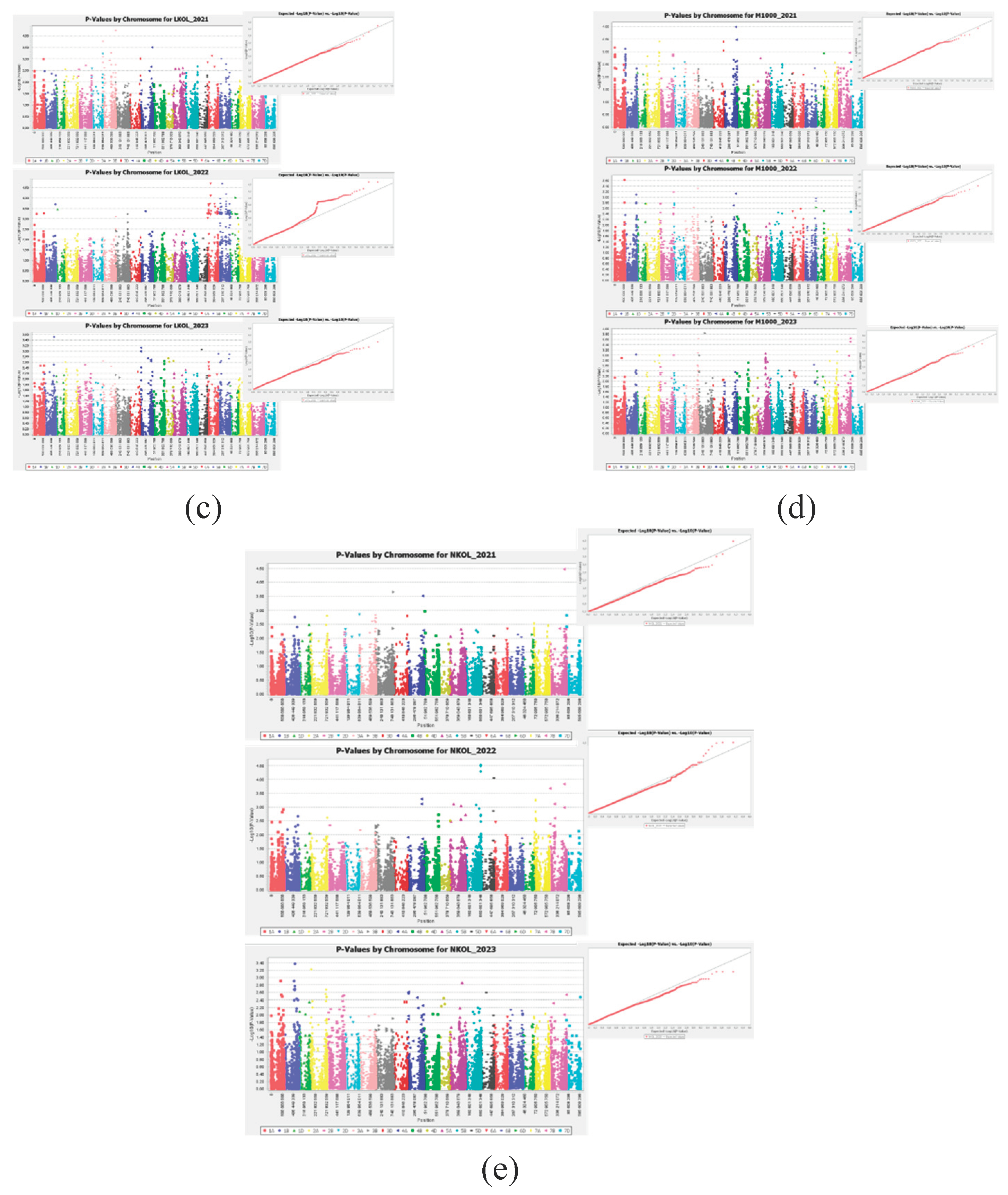

2.3. Association Analysis

2.3.1. Productivity

2.3.2. Technological Evaluation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Genotyping Data

4.2. Field Experiment and Phenotyping

4.3. DNA Isolation

4.4. Sample Genotyping

4.5. Population Structure

4.6. Statistical Analysis

4.7. Association Analysis

4.8. Technological Evaluation of Grain

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masalov, V.N.; Berezina, N.A.; Chervonova, I.V. The state of the grain farming in Russia, the role of grain crops in the feeding of agricultural animals and hu-man diet. Vestnik agrarnoj nauki, 2021, 89, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, A.A.; Andersson, R.; Piironen, V.; Lampi, A.M.; Nystrom, L. , Boros, D., Aman, P. Contents of dietary fibre components and their relation to associat-ed bioactive components in whole grain wheat samples from the HEALTHGRAIN diversity screen. Food chemistry. 2013, 136, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrier, L.D.; Ramsay, B.; Russell, J.; Milner, S.G.; Hedley, P.E.; Shaw, P.D.; Ma-caulay, M.; Halpin, C.; Mascher, M.; Fleury, D.L.; et al. Comparison of mainstream genotyping platforms for the evaluation and use of barley genetic resources. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.L.; Fickus, E.W.; Cregan, P.B. Characterization of trinucleotide SSR motifs in wheat // Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 104, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.C.; Gu, Y.Q.; Puiu, D. , Wang, H.; Twardziok, S.O.; Deal, K.R.; Huo, N.; Zhu, T.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Genome sequence of the progenitor of the wheat D genome Aegilops tauschii. Nature 2017, 551, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccaferri, M.; Harris, N.S.; Twardziok, S.O.; Pasam, R.K.; Gundlach, H.; Span-nagl, M.; Ormanbekova, D.; Lux, T.; Prade, V.M.; Milner, S.G. Durum wheat genome highlights past domestication signatures and future improvement tar-gets. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.Q.; Ma, B.; Shi, X.; Liu, H.; Dong, L.; Sun, H.; Cao, Y.; Gao, Q.; Zheng, S.; Li, Y. Genome sequence of the progenitor of wheat A subgenome Triticum urartu. Nature 2018, 557, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Gahlaut, V.; Meher, P.K.; Mir, R.R.; Jaiswal, J.P.; Rao, A.R.; Balyan, H.S.; Gupta, P.K. Genome Wide Single Locus Single Trait, Multi-Locus and Mul-ti-Trait Association Mapping for Some Important Agronomic Traits in Common Wheat (T. aestivum L.). PLoS ONE 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.G.; Fan, J.B.; Siao, C.J.; Berno, A.; Young, P.; Sapolsky, R.; Ghandour, G.; Perkins, N.; Winchester, E.; Spencer, J.; et al. Large-scale identification, mapping, and genotyping of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the human genome. Science. 1998, 280, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juliana, P.; Singh, R.P.; Singh, P.K.; Poland, J.A.; Bergstrom, G.C.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Bhavani, S.; Crossa, J.; Sorrells, M.E. Genome-wide association mapping for re-sistance to leaf rust, stripe rust and tan spot in wheat reveals potential candidate genes. Theor Appl Genet. 2018, 131, 1405–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, D.; Alqudah, A.M.; Ganal, M.W.; Schnurbusch, T. Genome-wide association analyses of 54 traits identified multiple loci for the determination of floret fertility in wheat. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatta, M.; Shamanin, V. et. al. Marker-Trait Associations for Enhancing Agro-nomic Performance, Disease Resistance, and Grain Quality in Synthetic and Bread Wheat Accessions in Western Siberia. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2019, 9, 4209–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klug, W.; Cummings, M.; et al. Essentials of Genetics. - Moscow: Tekhnosphere. 2021. Available online: https://www.studentlibrary.ru/book/ISBN9785948366234.html (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Kristensen, P.S. Genome-Wide Association Studies and Comparison of Models and Cross-Validation Strategies for Genomic Prediction of Quality Traits in Ad-vanced Winter Wheat Breeding Lines. Frontiers in plant science. 2018, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 15 Donini, P.; Law, J.R.; Koebner, R.M.D.; Reeves, J.C.; Cooke, R.J. Temporal trends in the diversity of UK wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2000, 100, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manifesto, M.M.; Schlatter, A.R.; Hopp, H.E.; Suarez, E.Y.; Dubcovsky, J. Quanti-tative evaluation of genetic diversity in wheat germplasm using molecular markers. Crop Sci. 2001, 41, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlestkina, E.K.; Huang, X.; Quenun, S.Y.B.; Chebotar, S.; Röder, M.S.; Börner, A. Genetic diversity in cultivated plants – loss or stability. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlestkina, E.K.; Röder, M.S.; Efremova, T.T.; Börner, A.; Shumny, V.K. The ge-netic diversity of old and modern Siberian varieties of common spring wheat de-termined by microsatellite markers. Plant Breed. 2004, 123, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, E.V.; Pshenichnikova, T.A.; Simonov, A.V.; Shchukina, L.V.; Chistya-kova, A.K.; Khlestkina, E.K. A comparative study of grain and flour quality pa-rameters among Russian bread wheat cultivars developed in different historical periods and their association with certain molecular markers. EWAC Newsl. 2016, 16, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Marone, D.; Russo, M.A.; Mores, A.; Ficco, D.B.M.; Laidò, G.; Mastrangelo, A.M.; Borrelli, G.M. Importance of Landraces in Cereal Breeding for Stress Tolerance. Plants. 2021, 10, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Kumari, J.; Jacob, S.R.; Prasad, P.; Gangwar, O.P.; Lata, C.; Thakur, R.; Singh, A.K.; Bansal, R.; Kumar, S.; et al. Landrac-es-potential treasure for sustainable wheat improvement. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2022, 69, 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakova, M.F.; Chistyakova, A.K.; Shchukina, L.V.; Morozova, E.V.; Khlestkina, E.K.; Pshenichnikova, T.A. The diversity of Siberian bread wheat cultivars on grain quality in dependence of breeding period. EWAC Newsletter. 2008, 14, 174–176. [Google Scholar]

- Mulugeta, B.; Tesfaye, K.; Ortiz, R.; Geleta, M.; Haileselassie, T.; Hammenhag, C.; Hailu, F.; Johansson, E. Unlocking the genetic potential of Ethiopian durum wheat landraces with high protein quality: Sources to be used in future breeding for pasta production. Food and Energy Security. 2024, 13, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlestkina, E.K.; Pshenichnikova, T.A.; Usenko, N.I.; Otmakhova, Yu.S. Promising opportunities of using molecular genetic approaches for managing wheat grain technological properties in the context of the “grain–flour–bread” chain. Russian Journal of Genetics: Applied Research. 2017, 7, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuluev, B.R.; Mikhailova, E.V.; Kuluev, A.R.; Galimova, A.A.; Zaikina, E.A.; Khlestkina, E.K. Genome Editing in Species of the Tribe Triticeae with the CRISPR/Cas System. Mol Biol (Mosk). 2022, 56, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Xu, D.; Bian, Y.; Liu, B.; Zeng, J.; Xie, L.; Liu, S.; Tian, X.; Liu, J.; Xia, X.; et al. Fine mapping and characterization of a major QTL for plant height on chromosome 5A in wheat. Theor Appl Genet 2023, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Lillemo, M.; Shi, J.; Wu, J.; Bjørnstad, Å.; Belova, T.; Dreisigacker, S.; Duveiller, E.; Singh, P. QTL characterization of fusarium head blight resistance in CIMMYT bread wheat line soru#1. PLoS ONE, 2016, 11, e158052. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, F.; Qin, D.; Li, M.; Fedak, G.; Cao, W.; Yang, L.; Dong, J. Molecular mapping of QTLs conferring fusarium head blight resistance in Chinese wheat cultivar Jingzhou 66. Plants 2020, 9, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Liu, D.; Qi, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhen, W. Major QTL for seven yield-related traits in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Frontiers in Genetics. 2020, 11, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 30 Ji, G.; Xu, Z.; Fan, X. Identification of a major and stable QTL on chromo-some 5A confers spike length in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Mol Breeding. 2021, 41, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marza, F.; Bai, G.H.; Carver, B.F.; Zhou, W.C. Quantitative trait loci for yield and related traits in the wheat population Ning7840 x Clark. Theor Appl Genet. 2006, 112, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Li, J.; Ding, A.; Zhao, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Bao, Y.; Li, X.; Feng, D.; Kong, L.; et al. Conditional QTL mapping for plant height with respect to the length of the spike and internode in two mapping populations of wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2011, 122, 1517–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sourdille, P.; Tixier, M.; Charmet, G. Location of genes involved in ear compactness in wheat (Triticum aestivum) by means of molecular markers. Mo-lecular Breeding 2006, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.G.; Bergman, C.J.; Gualberto, D.G.; Anderson, J.A.; Giroux, M.J.; Hareland, G.; Fulcher, R.G.; Sorrells, M.E.; Finney, P.L. Quantitative Trait Loci Associated with Kernel Traits in a Soft Hard Wheat Cross. Crop Sci. 1999, 39, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Q.; Coster, H.; Ganal, M.W.; Roder, M.S. Advanced backcross QTL analysis for the identification of quantitative trait loci alleles from wild relatives of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003, 106, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramya, P.; Chaubal, A.; Kulkarni, K.; Gupta, L.; Kadoo, N.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Chhuneja, P.; Lagu, M.; Gupt, V. QTL mapping of 1000-kernel weight, kernel length, and kernel width in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Appl. Genet. 2010, 51, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jia, J.; Wei, X.Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Chen, H.; Fan, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhao, X.; Lei, T.; et al. A intervarietal genetic map and QTL analysis for yield traits in wheat. Mol. Breed. 2007, 20, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marza, F.; Bai, G.H.; Carver, B.F.; Zhou, W.C. Quantitative trait loci for yield and related traits in the wheat population Ning7840 x Clark. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 112, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jia, L.; Lu, L.; Qin, D.; Zhang, J.; Guan, P.; Ni, Z.; Yao, Y.; Sun, Q.; Peng, H. Mapping QTLs of yield-related traits using RIL population derived from common wheat and Tibetan semi-wild wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 2415–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roder, M.S.; Huang, X.Q.; Borner, A. Fine mapping of the region on wheat chro-mosome 7D controlling grain weight. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2008, 8, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-Y.; Wu, K.; Zhao, Y.; Kong, F.-M.; Han, G.-Z.; Jiang, H.-M.; Huang, X.-J.; Li, R.-J.; Wang, H.-G.; Li, S.-S. QTL analysis of kernel shape and weight using recom-binant inbred lines in wheat. Euphytica 2009, 165, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, J.; Scott, P.; Leverington-Waite, M.; Turner, A.S.; Brinton, J.; Korzun, V.; Snape, J.; Uauy, C. Identification and independent validation of a stable yield and thousand grain weight QTL on chromosome 6A of hexaploid wheat (Triti-cum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanke, C.D.; Ling, J.; Plieske, J.; Kollers, S.; Ebmeyer, E.; Korzun, V.; Argillier, O.; Stiewe, G.; Hinze, M.; Neumann, F.; et al. Analysis of main effect QTL for thou-sand grain weight in European winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by ge-nome-wide association mapping. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Wu, L.; Gan, X.; Chen, W.; Liu, B.; Fedak, G.; Zhang, B. Mapping quantitative trait loci for 1000-grain weight in a double haploid population of common wheat. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asplund, L.; Bergkvist, G.; Leino, M.W.; Westerbergh, A.; Weih, M. Swedish spring wheat varieties with the rare high grain protein allele of NAM-B1 differ in leaf senescence and grain mineral content. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khlestkina, E.K.; Giura, A.; Röder, M.S.; Börner, A. A new gene controlling the flowering response to photoperiod in wheat. Euphytica 2009, 165, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pshenichnikova, T.A.; Ermakova, M.F.; Chistyakova, A.K.; Shchukina, L.V.; Bere-zovskaya, E.V.; Lochwasser, U.; Roeder, M.; Berner, A. Mapping of quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with quality indicators of soft wheat grain grown un-der various environmental conditions. Genetics 2008, 44, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli, G.M.; Troccoli, A.; Di Fonzo, N.; Fares, C. Durum wheat lipoxygenase ac-tivity and other quality parameters that affect pasta color. Cereal Chemistry 1999, 76, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessler, T.G.; Thomson, M.J.; Benscher, D.; Nachit, M.M.; Sorrells, M.E. Associa-tion of a lipoxygenase locus, Lpx-B1, with variation in lipoxygenase activity in durum wheat seeds. Crop Science 2002, 42, 1695–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, F.; Wu, P.; Zhang, N.; Cui, D. Molecular characterization of lipoxygenase genes on chromosome 4BS in Chinese bread wheat (Triticum aes-tivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet 2015, 128, 1467–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.D.; Chalmers, K.J.; Rathjen, A.J.; Langridge, P. Mapping loci associated with flour colour in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet 1998, 97, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.D.; Langridge, P. Development of a STS marker linked to a major locus controlling flour colour in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Mol. Breeding 2000, 6, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Y.; He, Z.H.; Ma, W.; Appels, R.; Xia, X.C. Allelic variants of phytoene syn-thase 1 (Psy1) genes in Chinese and CIMMYT wheat cultivars and development of functional markers for flour colour. Mol. Breeding 2009, 23, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, A.; Echenique, V.; Zhang, W.; Helguera, M.; Manthey, F.; Schrager, A.; Picca, A.; Cervigni, G.; Dubcovsky, J. A deletion at the LpxB1 locus is associated with low lipoxygenase activity and improved pasta color in durum wheat (Triti-cum turgidum ssp. durum). J. Cereal Science 2007, 45, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorofeev, V.F.; Filatenko, A.A.; Migushova, E.F.; Udachin, R.A.; Jacubziner, M.M. Cultural Flora of USSR. Wheat; Kolos: Leningrad, Russia, 1979; pp. 1–348. [Google Scholar]

- Merezhko, A.F.; Udachin, R.A.; Zuev, E.V.; Filatenko, A.A.; Serbin, A.A.; Lyapun-ova, O.A.; Kosov, V.Yu.; Kurkiev, U.K.; Okhotnikova, T.V.; Navruzbekov, N.A.; et al. Replenishment, preservation and study of the world's collection of wheat, aegilops and triticale. (Methodological instructions). St. Petersburg, VIR 1999, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani, B.; Lehnert, H.; Keilwagen, J.; Plieske, J.; Ordon, F.; Naseri Rad, S.; Perovic, D. Comparison between core set selection methods using different Illu-mina marker platforms: A case study of assessment of diversity in wheat. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2020, 11, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.M.; Winfield, M.O.; Burridge, A.J.; Downie, R.; Benbow, H.R.; Barker, G.L.A.; Wilkinson, P.A. (2016) Characterisation of a wheat breeders’ array suitable for high throughput SNP genotyping of global accessions of hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum). Plant Biotechnol. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dospehov, B.A. Methodology of field experience (with the basics of statistical processing of research results). M.: Book on Demand. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, P.J.; Zhang, Z.; Kroon, D.E.; Casstevens, T.M.; Ramdoss, Y.; Buckler, E. ST ASSEL: Software for association maping of complex traits in diverse sam-ples. BIOINFORMATICS. 2007, Т. 23, №19, 2633–2635. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Turner, R. Power analysis for random-effects meta-analysis. Research synthesis methods 2017, 8, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, O.; Viechtbauer, W. The poolr Package for Combining Independent and Dependent p Values. J. Stat. Softw. 2022, 101, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyholt, D.R. A simple correction for multiple testing for single-nucleotide poly-morphisms in linkage disequilibrium with each other. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2004, 74, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilenko, I.I.; Komarov, V.I. Grain quality assessment: Reference book. M.: Ag-ropromizdat. 1987, 208. [Google Scholar]

- Bebyakin, V.M.; Buntina, M.V. Efficiency of grain assessment of spring soft wheat using the SDS test. Vestnik Agricultural Sciences. Sci. 1991, No. 1, 66-70.N.; Berezina, N. A.; Chervonova, I. V. The state of the grain farming in Russia, the role of grain crops in the feeding of agricultural animals and human diet. Vestnik agrarnoj nauki 2021, 89, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

| Trait1 | Mean in during three years | Max | Min | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Resistance to lodging (RL) |

8,0±1,6 | 7±2,3 | 7,9±1,4 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Spike length (SL) |

8,4±1,0 | 8,3±1,2 | 7,1±1,0 | 11,6 | 11,2 | 9,5 | 4,7 | 4,1 | 3,3 |

| Рlant height (PH) |

92±11 | 103±14,7 | 86,1±14,9 | 110 | 140 | 125 | 60 | 73 | 52,5 |

| Thousand grain weight (TGW) |

33,1±5,6 | 45,9±6,8 | 31,4±7,2 | 46,6 | 61,7 | 49,4 | 20 | 23,1 | 14,7 |

| Number of spikelets in a spike (SN) |

14,7±1,5 | 15±2,0 | 13,3±2,1 | 19,2 | 22 | 20,2 | 11 | 9 | 8 |

| Trait | Marker | Chr | Position | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | RAC875_rep_c113313_607meta | 5A | 585240573 | 2,74E-06 |

| wsnp_Ex_c31799_405454782022,meta | 5A | 585403218 | 5,3E-07 | |

| wsnp_Ex_c31799_40545376meta | 5A | 585403320 | 1,08E-06 | |

| Excalibur_c7729_144meta | 5A | 585412831 | 1,05E-07 | |

| tplb0038h19_13942022,meta | 5A | 585431093 | 1,05E-06 | |

| RAC875_c9984_1003meta | 5A | 585458474 | 8,87E-07 | |

| wsnp_Ex_rep_c66689_650109882022,meta | 5A | 585609287 | 9.26E-08 | |

| BS00022071_512022,meta | 5A | 586604587 | 9.46E-08 | |

| TG0052meta | 5A | 587412057 | 1,08E-06 | |

| TG0053meta | 5A | 587412186 | 1.25E-06 | |

| TG00192022,meta | 5A | 587423597 | 9.74E-07 | |

| TG00412022,meta | 5A | 588550278 | 5,97E-08 | |

| wsnp_BF293620A_Ta_2_12022,meta | 5A | 588555309 | 1,04E-07 | |

| TA001896-0654meta* | 5A | 588848205 | 3,49E-06 | |

| AX-949207112023* | 5A | 609276661 | 9.01E-06 | |

| RL | wsnp_CAP11_rep_c4105_19409852021* | 2B | 448080584 | 1.91E-05 |

| tplb0050d17_14012021* | 6A | 613770166 | 3.87E-05 | |

| Tdurum_contig45618_10892023* | 7A | 736690246 | 9.18E-06 | |

| BS00024643_512023* | 2A | 779207402 | 4.98E-05 | |

| Excalibur_c16329_493meta* | 2D | 634296660 | 8.07E-05 | |

| SL | RAC875_c48456_444meta | 6B | 470800981 | 1,21E-06 |

| Excalibur_rep_c92855_977meta* | 6A | 410914096 | 3,8E-06 | |

| TGW | Excalibur_c4325_1150meta* | 4A | 684616475 | 2,38E-05 |

| SN | AX-94505099meta* | 7B | 648926257 | 6,31E-06 |

| Structural indicators | Indicators | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein, % | Ash content, % | Flour colour, % | Grain unit, g/L | Sedimentation value, mL | |

| Limits of variation | 11,5-20,7 | 1,53-2,80 | 74,8-84,1 | 622-832 | 16-82 |

| Experiment mean value | 14,79 | 1,99 | 81,27 | 760,27 | 61,49 |

| F-criterion (intervarietal) | 3,51* | 3,19* | 1,76* | 2,75* | 3,62* |

| НСР | 2,22 | 0,27 | 3,83 | 45,28 | 13,44 |

| Trait | Marker | Chr | Position | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hectolitre weight | Excalibur_c82557_201* | 1A | 9123021 | 7.20E-05 |

| BS00009789_51* | 5A | 451478823 | 2.85E-05 | |

| BobWhite_c8202_245* | 5A | 445191670 | 9.29E-05 | |

| IAAV8870* | 5B | 473114741 | 1.64E-05 | |

| AX-94541836* | 5B | 572140495 | 6.59E-05 | |

| BobWhite_rep_c48956_706* | 6A | 149925808 | 8.25E-05 | |

| IAAV8065* | 6B | 411097830 | 8.22E-05 | |

| RAC875_c17185_90* | 7A | 20164436 | 6.49E-05 | |

| Kukri_c49828_316* | 7B | 702501105 | 6.77E-05 | |

| Protein content | IAAV5730 | 1A | 344480854 | 5.00E-06 |

| TA004690-1102 | 1D | 435801686 | 3.33E-06 | |

| AX-94602991 | 2A | 776022491 | 3.28E-06 | |

| IACX8602 | 2A | 776040004 | 3.33E-06 | |

| JD_c63957_1176* | 2D | 20769330 | 2.20E-05 | |

| Аsh content | AX-94726440* | 3A | 197860384 | 6.66E-06 |

| BS00065543_51* | 5B | 17575036 | 7.19E-06 | |

| AX-94519170* | 6D | 464735570 | 4.00E-06 | |

| RAC875_c17185_90* | 7A | 20164436 | 1.25E-05 | |

| Flour color | Kukri_c57491_156* | 2B | 440825097 | 4.34E-06 |

| wsnp_Ex_c19647_28632894 | 5A | 470033197 | 1.87E-06 | |

| wsnp_JD_c6160_7327405 | 5A | 472344585 | 1.87E-06 | |

| RFL_Contig2187_1025 | 5A | 472346644 | 1.87E-06 | |

| IACX12578 | 5A | 467379740 | 2.71E-06 | |

| BobWhite_c46338_76 | 5A | 468462719 | 2.71E-06 | |

| Kukri_c17430_972 | 5A | 468467336 | 2.71E-06 | |

| AX-94436930* | 5A | 473312305 | 5.69E-06 | |

| RAC875_c79944_269* | 5A | 468463193 | 7.50E-06 | |

| Flour sedimentation | Kukri_c9898_1766 | 0 | 0 | 2.91E-08 |

| AX-94881376 | 1A | 30136011 | 3.78E-08 | |

| wsnp_BF474340A_Ta_2_1 | 1A | 556942097 | 4.63E-08 | |

| IAAV5776 | 1B | 675560975 | 3.13E-06 | |

| AX-94414376* | 1B | 552777509 | 6.20E-06 | |

| AX-95213897* | 2A | 510805288 | 9.11E-06 | |

| Kukri_c63797_354 | 3B | 761853919 | 1.89E-08 | |

| AX-94467468* | 4A | 599326520 | 9.08E-06 | |

| Tdurum_contig8028_870* | 4B | 586069506 | 5.78E-06 | |

| wsnp_Ku_c23772_33711538 | 5A | 476603824 | 4.11E-08 | |

| RAC875_rep_c109969_119 | 5A | 593332300 | 3.40E-07 | |

| RAC875_c2105_740 | 5B | 555011247 | 3.68E-08 | |

| Kukri_c13224_551 | 5B | 87230041 | 3.95E-08 | |

| AX-94878420 | 5B | 449201643 | 4.28E-08 |

| Accessions status | Number of wheat accessions | |

|---|---|---|

| from Russia | from Germany | |

| Lamdraces | 19 | 10 |

| Breeding varieties before 1950 | 19 | 51 |

| Breeding varieties 1951-1991 | 42 | 30 |

| Modern breeding varieties | 14 | 1 |

| Total | 94 | 92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).