Submitted:

02 March 2024

Posted:

04 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Setting the Agenda

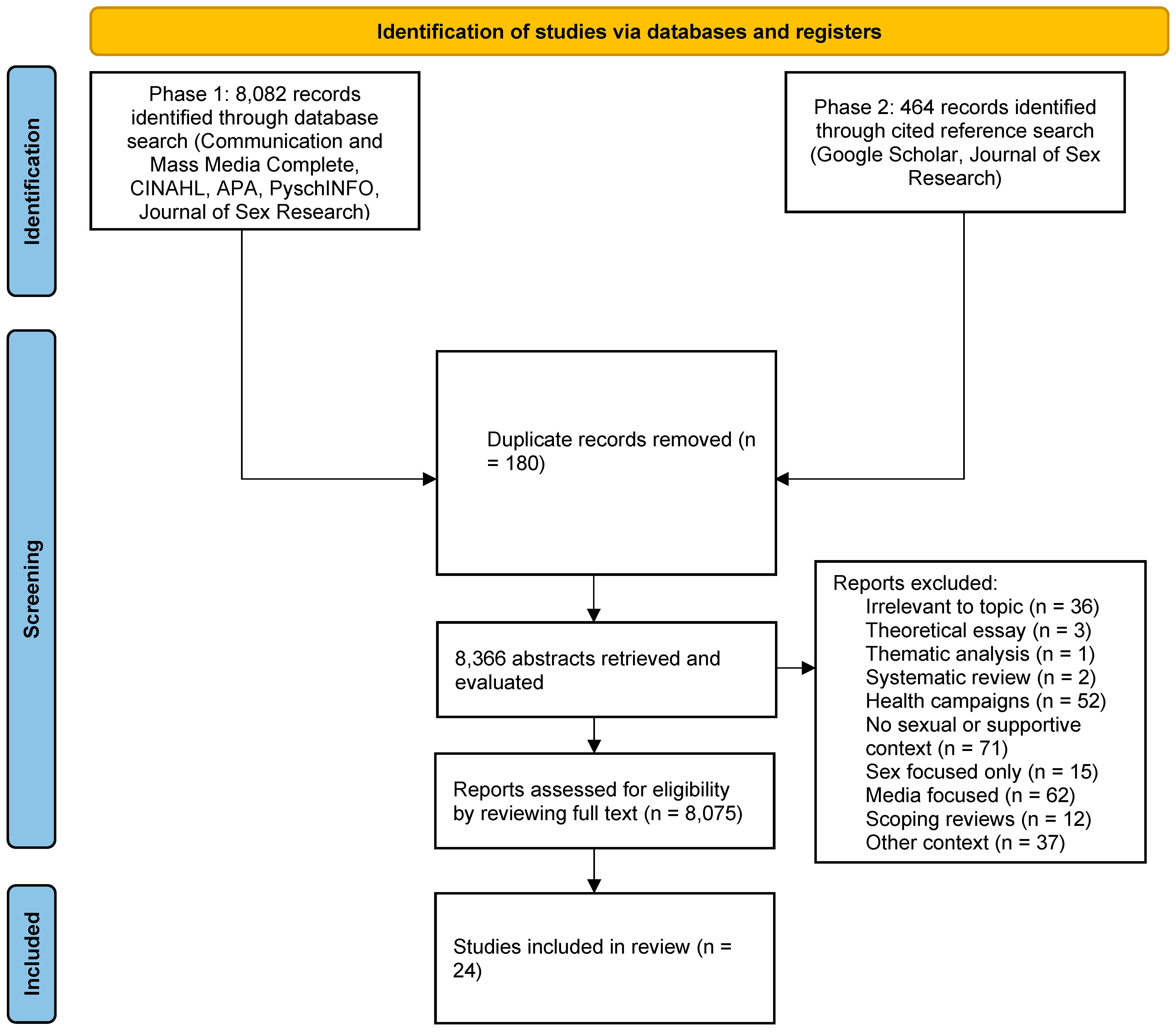

Method

Search Strategy

Inclusion Criteria

Data Extraction

Results

Sample and Study Characteristics

Theories Guiding Sexual Communication Research

Context of Sexual Communication Research

Communicative Outcomes

Sexual Communication as an Interaction and Dynamic Process

Key Constructs in Sex Communication Research

Discussion

Application of Theoretical Frameworks

Contextualizing Sex-Talk Research

Theoretical Tenets to Guide Development of a Sex Talk Theory

Limitations and Future Directions

Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afifi, W. A., & Caughlin, J. P. (2006). A close look at revealing secrets and some consequences that follow. Communication Research, 33(6), 467-488. [CrossRef]

- Afifi, T., & Steuber, K. (2009). The revelation risk model (RRM): Factors that predict the revelation of secrets and the strategies used to reveal them. Communication Monographs, 76(2), 144-176. [CrossRef]

- Albritton, T., Fletcher, K. D., Divney, A., Gordon, D., Magriples, U., & Kershaw, T. S. (2014). Who’s asking the important questions? Sexual topics discussed among young pregnant couples. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(6), 1047-1056. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, L. A., & Wilmot, W. W. (1985). Taboo topics in close relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 2(3), 253-269. [CrossRef]

- Berger, C. R. (2010). Making a differential difference. Communication Monographs, 77(4), 444-451. [CrossRef]

- Brisini, K. S. C., Solomon, D. H., & Tian, X. (2022). Relational turbulence and openness to social network support for marital conflicts. Western Journal of Communication, 86(1), 83-102. [CrossRef]

- Burleson, B. R., Hanasono, L. K., Bodie, G. D., Holmstrom, A. J., McCullough, J. D., Rack, J. J., & Rosier, J. G. (2011). Are gender differences in responses to supportive communication a matter of ability, motivation, or both? Reading patterns of situation effects through the lens of a dual-process theory. Communication Quarterly, 59(1), 37-60. [CrossRef]

- Cornacchione, J., & Smith, S. W. (2017). Female Offenders’ MultipleGoalsfor Engaging in Desired Communication with Their Probation/Parole Officers. Communication Quarterly, 65(1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Chaudoir, S. R., & Fisher, J. D. (2010). The disclosure processes model: understanding disclosure decision making and postdisclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 236. [CrossRef]

- Curran, T. M., Monahan, J. L., Samp, J. A., Coles, V. B., DiClemente, R. J., & Sales, J. (2016). Sexual risk among African American women: Psychological factors and the mediating role of social skills. Communication Quarterly, 64(5), 536-552. [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, S. L., & Lannutti, P. J. (2010). Examining the content and outcomes of young adults’ satisfying and unsatisfying conversations about sex. Qualitative Health Research, 20(3), 375-385. [CrossRef]

- Fedd, A., & Samp, J. A. (2023). “Let’s talk about sex”: Expanding advice response theory to sexual advice-seeking. Southern Communication Journal. 88(3), 266-278. [CrossRef]

- Francis, D. B., Zelaya, C. M., Fortune, D. A., & Noar, S. M. (2021). Black college women’s interpersonal communication in response to a sexual health intervention: A mixed methods study. Health Communication, 36(2), 217-225. [CrossRef]

- Grossman, J. M., Jones, C., & Richer, A. M. (2022). ‘I put it all out there. I have nothing to hide. It’s my mom’: parents’ and emerging adults’ perspectives on family talk about sex. Sex Education, 23(4), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Haeffel, G. J., & Howard, G. S. (2010). Self-report: Psychology’s four-letter word. The American Journal of Psychology, 123(2), 181-188. Haeffel, G. J., & Howard, G. S. (2010). Self-report: Psychology’s four-letter word. The American journal of psychology, 123(2), 181-188.

- Harwood, J. (2010). A difference we can call our own. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 38(3), 295-298. [CrossRef]

- High, A. C., & Solomon, D. H. (2016). Explaining the durable effects of verbal person-centered supportive communication: Indirect effects or invisible support? Human Communication Research, 42(2), 200-220. [CrossRef]

- Holmstrom, A. J., Bodie, G. D., Burleson, B. R., McCullough, J. D., Rack, J. J., Hanasono, L. K., & Rosier, J. G. (2015). Testing a dual-process theory of supportive communication outcomes: How multiple factors influence outcomes in support situations. Communication Research, 42(4), 526-546. [CrossRef]

- Holmstrom, A. J., Reynolds, R. M., Shebib, S. J., Poland, T. L., Summers, M. E., Mazur, A. P., & Moore, S. (2021). Examining the Effect of Message Style in Esteem Support Interactions: A Laboratory Investigation [Article]. Journal of Communication, 71(2), 220-245. [CrossRef]

- Horan, S. M., Morgan, T., & Burke, T. J. (2018). Sex and Risk: Parental Messages and Associated Safety/Risk Behavior of Adult Children [Article]. Communication Quarterly, 66(4), 403-422. [CrossRef]

- Impett, E. A., Muise, A., & Peragine, D. (2014). Sexuality in the context of relationships. In D. L. Tolman, L. M. Diamond, J. A. Bauermeister, W. H. George, J. G. Pfaus, & L. M. Ward (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology, Vol. 1. Person-based approaches (pp. 269–315). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, L., & Theiss, J. (2011). Relational Uncertainty and Relationship Talk within Courtship: A Longitudinal Actor-Partner Interdependence Model [Article]. Communication Monographs, 78(1), 3-26. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, K., & Gettings, P. E. (2021). Uncertainty management in sexual communication: Testing the moderating role of marital quality, relational closeness, and communal coping. Health Communication, 36(11), 1368-1377. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Mikels, J. A., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. L. (2021). The psycholinguistic and affective processing of framed health messages among younger and older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 27(2), 201–212. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Samp, J. A., Coles Cone, V. B., Mercer Kollar, L. M., DiClemente, R. J., & Monahan, J. L. (2018). African American Women’s Language Use in Response to Male Partners’ Condom Negotiation Tactics. Communication studies, 69(1), 67-84. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Samp, J. A. (2019). Predictors and outcomes of initial coming out messages: Testing the theory of coming out message production. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 47(1), 69-89. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Samp, J. A. (2021). Predictors and outcomes of LGB individuals’ sexual orientation disclosure to heterosexual romantic partners. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 49(1), 24-43. [CrossRef]

- McManus, T. G. (2020). Providing support to friends experiencing a sexual health uncertainty. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 48(4), 515-536. [CrossRef]

- McManus, T. G., & Lucas, A. A. (2018). Received support from friends about sex-related concerns: A multiple goals perspective. Communication Reports, 31(3), 143-158. [CrossRef]

- Mongeau, P. A., Serewicz, M. C. M., & Therrien, L. F. (2004). Goals for cross-sex first dates: identification, measurement, and the influence of contextual factors. Communication Monographs, 71(2), 121-147. [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y., Wu, Y., Wang, J., Wu, Y., Li, Z., & Cui, Y. (2020). Safer Sex Practice Among Female Chinese College Students and Its Antecedents: A Culture-Centered Approach. International Journal of Sexual Health, 32(3), 282-292. [CrossRef]

- Muise, A., Maxwell, J. A., & Impett, E. A. (2018). What theories and methods from relationship research can contribute to sex research. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4-5), 540-562. [CrossRef]

- Nan, X. (2012). Communicating to Young Adults About HPV Vaccination: Consideration of Message Framing, Motivation, and Gender [Article]. Health Communication, 27(1), 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Nan, X., Daily, K., Richards, A., & Holt, C. (2019). Parental Support for HPV Vaccination Mandates Among African Americans: The Impact of Message Framing and Consideration of Future Consequences [Article]. Health Communication, 34(12), 1404-1412. [CrossRef]

- Omarzu, J. (2000). A disclosure decision model: Determining how and when individuals will self-disclose. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 174-185. [CrossRef]

- Petronio, S. (2002). Boundaries of privacy: Dialectics of disclosure. Suny Press.

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371-385. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A. A. (2017). Parent–adolescent sexual communication and adolescents’ sexual behaviors: A conceptual model and systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 2, 293-313. [CrossRef]

- Roloff, M. E. (2015). Theorizing interpersonal communication: Progress and Problematic Practices. Communication Theory, 25(4), 1050-3293. [CrossRef]

- Rubinsky, V., & Cooke-Jackson, A. (2018). Sex as an intergroup arena: How women and gender minorities conceptualize sex, sexuality, and sexual health. Communication Studies, 69(2), 213-234. [CrossRef]

- Shebib, S. J., Holmstrom, A. J., Mason, A. J., Mazur, A. P., Zhang, L., & Allard, A. (2020). Sex and Gender Differences in Esteem Support: Examining Main and Interaction Effects. Communication Studies, 71(1), 167-186. [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, P. J., Tankard Jr, J. W., & Lasorsa, D. L. (2004). How to build social science theories. Sage.

- Simms, D. C., & Byers, E. S. (2013). Heterosexual daters’ sexual initiation behaviors: Use of the theory of planned behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(1), 105-116. [CrossRef]

- Theiss, J. A., & Estlein, R. (2014). Antecedents and consequences of the perceived threat of sexual communication: A test of the relational turbulence model. Western Journal of Communication, 78(4), 404-425. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., ... & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467-473. [CrossRef]

- Widman, L., Choukas-Bradley, S., Noar, S. M., Nesi, J., & Garrett, K. (2016). Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(1), 52-61. [CrossRef]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female only | 5 | 20.8% |

| Female and sexual minorities | 1 | 4.2% |

| Men and women | 16 | 66.7% |

| Did not specify gender identity | 2 | 8.3% |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Heterosexual onlya | 13 | 54.2% |

| LGB | 3 | 12.5% |

| Relational Type | ||

| Single | 13 | 54.2% |

| Married | 2 | 8.3% |

| Dating | 7 | 29.2% |

| Parent-Child | 1 | 4.2% |

| Did not specify | 1 | 4.2% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black/African American Onlyb | 4 | 16.8% |

| White | 17 | 70.8% |

| Hispanic/Latin(x)(a)(o) | 15 | 62.5% |

| Asian/Asian American | 12 | 50% |

| Black/African American | 14 | 58.3% |

| Native American | 4 | 16.8% |

| Otherc | 12 | 50% |

| Country | ||

| U.S. | 22 | 91.7% |

| Non-U.S. study | 2 | 8.3% |

| Study Authors | Theory | Context/Topic | Study Design | Sample Size | Communicative Outcome | Themes | Main Findings |

| Afifi & Weiner (2006) | TMIM | Information-seeking about sexual health problem | Quantitative (wave 1 and wave 2 individual survey) 129 males; 136 females |

Experimental (n = 92), control group (n = 97), or no-pretest group (n = 77) | Information-seeking about sexual health | Measured components of efficacy Sexual assertiveness Sexual decision-making |

Disclosure Ability and willingness to disclose sexual health information. Cognition Evaluation of cost/benefits analysis of seeking sexual health information. Other Develop theory that examines ability and willingness to produce messages; examine perceptual bias. |

| Albritton et al. (2014) | Ecological Model | Sexual risk communication among young pregnant couples | Quantitative (cross-sectional dyadic survey) |

296 expecting couples |

Sexual risk communication | Individual, interpersonal, and social level factors |

Disclosure Women disclose more sexual information than men. Other Interventions to improve sexual communication skills. |

| Brisini et al. (2022) | RTT | Relational turbulence and supportive messages | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 479 individuals | Support quality | Relational/social support Psychological reactance Person-centered messages |

Disclosure Ability and willingness to disclose issue to a relational source. Cognition Chaos influence evaluation about the meaning of supportive messages. Other Supportive others should engage in perspective taking. |

| Burleson et al. (2011) | DPT of Supportive Communication | Processing supportive messages | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 207 individuals (i.e., study 1); 103 individuals (i.e., study 2) | Comforting messages (i.e., study 1); grief management messages (i.e., study 2) | Processing ability; relational/social support |

Cognition Women’s ability and motivation to process supportive messages higher than men. |

| Cornaccione & Smith (2017) | Multiple Goals Perspective | Women on probation and parole officers | Quantitative survey; open-ended questions | 402 women in quantitative; 394 women in qualitative | Difficult issues/needs | Relational/social support Primary and secondary goals |

Other Situational factors influence how women initiate conversations with parole officers. |

| Curran et al. (2016) | Social skills deficit hypothesis | Sexual risk among African American women | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) |

557African American women | Sexual risk communication | Sexual communication self-efficacy Destructive conflict tactics Social skills |

Disclosure Negative psychological factors decrease sexual communication self-efficacy. Cognition One’s own and communicative partners’ communication influence their conversational behaviors Other Sexual health interventions should address social skills with main partners. |

| Francis et al. (2021) | IMBe and TGP | Sexual health intervention to generate conversations among Black women | Mixed methods | 105 women (survey) 10 women (interview) |

Intervention to examine condom dispenser uptake | Relational partners matter Examine condom use social norms |

Other Communication partners, content, mode, valence, and impact influenced positive interaction with condom dispenser. |

| High & Solomon (2016) | Indirect Effects Model (dual-process theory) | Long-term effects of supportive messages | Quantitative (cross-sectional dyadic survey) | 255 dyads | Message evaluations and message outcomes, respectively | Cognitive awareness Sex differences in cognitive processes |

Cognition Thorough scrutiny of supportive messages is influenced by higher levels of communicative ability and motivation. |

| Holmstrom et al. (2015) | DPT of Supportive Communication | Testing the complex interactions of source, message, contextual, and recipient constructs | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) |

328 individuals | Perceived support availability and Severity of problem on support quality, respectively |

Relational status with recipient Environmental cues Memory |

Cognition The severity of the problem and perceived support availability influence motivation to process supportive messages. Other Comprehensive theory is needed to explain how and why supportive messages have the effects they do. |

| Holmstrom et al. (2021) | CETESM | Emotion-focused versus problem-focused esteem messages | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) |

173 individuals | Esteem-supportive messages | Message content Style of message Degree, quantity, and relevance |

Disclosure Discussing esteem threatening situation and receiving emotion-focused esteem support influence greater state self-esteem. Cognitive What supportive others say has an impact on support recipients’ appraisal about the potential damage to their self-esteem. |

| Horan et al. (2018) | FCP and AET | Family communication patterns, sexual communication, and young adults’ safety/risks | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) |

195 individuals | Sexual risk communication | Communication patterns Communication about sex in families |

Disclosure Conversation orientations predict better open and are less avoidant to communicate about sex topics with parents. |

| Knobloch & Theiss (2011) | Relational Uncertainty | Relational uncertainty influence on relationship talks | Quantitative (cross-sectional dyadic survey) | 135 dyads | Longitudinal effects of relationship talk | Perceived threats to relationship Examining sensitive topics |

Other Relational uncertainty and relationship talk is a dynamic process that changes over time. |

| Kuang and Gettings (2011) | TMIM | Uncertainty discrepancy and information management | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 248 individuals | Information management in sexual communication | Examined how relational assessments moderate the associations of TMIM variables |

Disclosure Relational factors (i.e., marital quality, closeness, and communal coping) influence information management strategies. Cognitive Reappraisal of information |

| Li et al. (2018) | Multiple Goals Perspective | Sexual negotiation goals and goal pursuit | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 193 African American women | Language use in sexual settings | Self-oriented goals Other-oriented goals Relational goals |

Disclosure Language choice influence relevance of condom negotiation strategies. Other Sexual health interventions should consider the usage of personal pronouns in formative research efforts. |

| Liu et al. (2021) | SST | Promoting behaviors from a cognitive and emotional perspective | Quantitative (cross-sectional experimental survey) | 80 individuals | Framed health messages | Mental representation Perceived effectiveness Message processing |

Cognitive Loss-framed messages took longer to process that gain-framed messages. Cognitive processes influence emotional responses to framed health messages. |

| McManus (2020) | TMIM | Information management and sexual health expertise | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 424 individuals | Support provision about sexual health uncertainty | Communication and coping efficacy Experience Expertise |

Disclosure Communication and target efficacy have different effects on evaluation of support provision. Providers with more expertise provided less blame support. |

| McManus & Lucas (2018) | Multiple Goals Perspective | Multiple communicative goals in friend’s sex talk | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 139 individuals | Received support (i.e., information, tangible, and nurture) | Stigmatizing sex-related concerns Interaction goals |

Other Goals serve multiple functions in evaluating the meaning of messages about a sex-related concern. Goal interference is influenced by goal importance. |

| Mongeau et al. (2004) | Multiple Goals Perspective | First date goals | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 144 individuals (study 1) 241 individuals (study 2) 218 individuals (Study 3) |

Communicative goals |

Sociobiological sex differences (Study 1-3) Scale development (study 2) Situational context (study 3) |

Other Across all three studies individuals aim to reduce uncertainty during first dates. Multiple goal structures influence subsequent communicative interactions. |

| Mou et al. (2020) | IMB | Behavioral skills model to examine condom use | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 1,247 female individuals | Safer sex negotiation skills | Culture, context, and agency Sexual assertiveness Gender roles |

Other Contraceptive information and motivation influence safer sex practices. Gender roles influence holding traditional sexual values. |

| Nan (2012) | Congruence Hypothesis | HPV vaccine message frames | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 229 individuals | HPV vaccination intentions | Behavioral intentions Motivational behaviors Gender Efficacy |

Cognitive Avoidance-oriented individuals preferred more loss-frame messages than gain-frame individuals. Other Women were more concerned about HPV vaccine safety than men. |

| Nan et al. (2019) | Prospect Theory | HPV vaccination policy and African Americans parent support | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 211 individuals | HPV vaccine mandates | Perceived risk Persuasion |

Cognitive Individuals’ cognitive response to gain- and loss-frame messages is influenced by their construal. Other Health communication interventions should consider how specific populations consider future consequences regarding health behaviors. |

| Rubinsky & Cooke-Jackson (2018) | Communication Theory of Identity | Conceptualiza-tion of sex and sexuality | Qualitative study (open-ended questions) | 186 women and gender minorities | Define sex, sexuality, and sexual health | Gender Emotional health Sexual identity Framing of sexual scripts |

Disclosure Expressions of sexuality influence how people identify with sex talk (i.e., personal, enacted, and relational identity). Other Emotional experiences shape how individuals define sex. Women and gender minorities define sex as an activity and identity. |

| Shebib et al. (2020) | CETESM | Gender and sex differences in the provision of esteem support | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 396 individuals | Quality of esteem supportive messages | Gender differences Sex differences Emotion-focused Problem-focused |

Disclosure Females and individuals high in femininity produce highly emotional-focused messages. Biologically, females endorsed more problem-focused message to male support recipients. Cognitive Females and individuals high in femininity more frequently experience multiple cognitions and emotions associated with esteem threats. |

| Simms & Byers (2013) | Theory of Planned Behavior | Sexual initiation behaviors of romantic partners | Quantitative (cross-sectional individual survey) | 151 individuals | Sexual initiation behaviors | Gender Social norms Attitudes Behavioral intentions |

Cognitive Positive perceptions regarding partner approval and intentions influence sexual initiation outcomes. Sexual frequency associate with positive relational outcomes. Other Men endorsed more permissive sexual behaviors than women. Aligning with traditional sexual scripts. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).