1. Introduction

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is a neurotrophin for a subset of nociceptive sensory neurons and a protein that modulates the differentiation of developing peripheral neurons [

1]. During inflammation generated by unilateral injection of complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA), the level of NGF is elevated in the skin [

2]. NGF is also increased in various animal models mimicking inflammation, including carrageenan and formalin [

3,

4]. However, the expression pattern of NGF during the progressive phase of peripheral inflammation is not yet well defined.

Pain and inflammation are considered debilitating, but at the same time, they are also the protective responses necessary for survival. Pain is the mechanism that provides information about the presence or threat of an injury [

5]. In addition to the afferent function, such as conveying information to the central nervous system, the dorsal root ganglion primary sensory neurons, specifically C and some Aδ fibers, regulate the vascular and tissue function at their peripheral targets. For example, during neurogenic inflammation, tissue damage causes depolarization of the primary afferents, which releases neuropeptides such as Substance P (SP), Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP), and neurotransmitters such as glutamate, leading to increased vascular permeability and plasma extravasation [

6]. Due to this increased vascular permeability, the inflammation site recruits inflammatory cells such as T lymphocytes, mast cells, macrophages, and neutrophils [

7]. These cells change the chemical milieu at the site of injury/inflammation by releasing pro-inflammatory molecules such as prostaglandins, bradykinin, histamine, and serotonin. Cytokines such as interleukins (ILs), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and neurotrophins like NGF are released during inflammation [

8].

Inflammation in the periphery stimulates the sensitization of peripheral nerves and brings about changes in neuronal cells in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) by generating signals that travel in a backward direction in pain-sensing neurons. The retrograde signals activated by NGF in the opposite direction activate or boost the transcription of molecules that promote pain, such as neurotransmitters and neuropeptides, leading to an increase in both central and peripheral sensitization. [

1,

9]. To meet the considerable challenge of conveying information from the periphery to the cell body located far away, dedicated mechanisms of retrograde NGF signaling have evolved, which carry the signals generated from the axonal endings to the neuron’s cell body [

10]. Following NGF engagement, TrkA forms a heterodimer and gets autophosphorylated. This complex is internalized by clathrin-dependent endocytosis, which gives rise to signaling endosomes. It has been shown that the NGF signaling endosomes are multivesicular bodies (MVBs) that mediate long-range retrograde transport [

11].

Although the levels of NGF are upregulated after a noxious stimulus, the information regarding the expression pattern of NGF during the initial progression of peripheral inflammation is unknown. In this study, we determined the effect of AIA in rat skin on the time course alteration in the expression of NGF. For this purpose, we employed the unilateral AIA rat model and measured the rat’s hind paw’s metatarsal thickness to determine the severity of inflammation. We also evaluated the NGF protein and mRNA levels at different time points during the phasic progression of inflammation induced by AIA.

2. Results

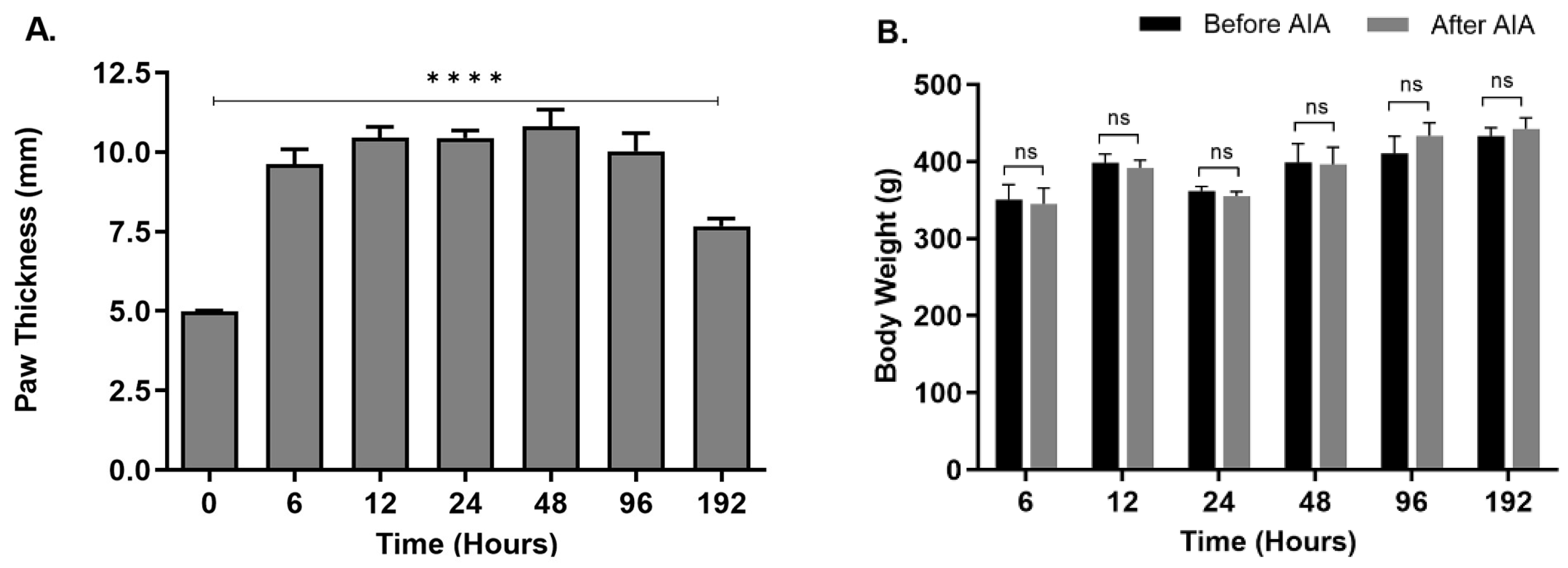

2.1. Changes in Hind Paw Edema and Body Weight

The metatarsal thickness of the ipsilateral posterior paws was significantly increased (p < 0.0001) in animals treated with CFA compared to the control untreated animals. The increased thickness was observed at all seven-time points, with the highest peak at 48 hours (

Figure 1A), suggesting a robust inflammatory response. An increase in the metatarsal thickness of rats suggests the presence of inflammation. This observation is consistent with known physiological reactions, where inflammation can cause tissue swelling by increasing blood vessel permeability and the buildup of immune cells and inflammatory substances at the inflamed location [

12]. In the experiment assessing the impact of increasing peripheral inflammation on NGF expression in rat epidermis, the rise in metatarsal thickness acts as a supporting sign of the inflammatory reaction caused by antigen-induced arthritis (AIA). The increased thickness in the metatarsal region indicates a specific swelling of tissues, perhaps caused by the inflammatory process initiated by AIA. Measuring the metatarsal thickness assist in determining the efficiency of the experimental model in replicating inflammatory conditions and highlights the need of investigating NGF expression in relation to inflammation-related diseases such as pain sensitivity and tissue damage. Bodyweight of animals after CFA treatment was not significantly different from the untreated animals at any of the seven-time points (

Figure 1B) suggesting that the animals did not experience significant distress as a direct result of the injection. This observation is crucial in assessing the welfare and well-being of the experimental animals throughout the study. Significant changes in body weight, such as a decrease, could indicate distress, discomfort, or adverse effects associated with the injection procedure or subsequent inflammatory response. However, the stable body weight suggests that the rats maintained their physiological equilibrium and were not adversely affected by the CFA injection in terms of their overall health and nutritional status during the monitored period. This finding provides important reassurance regarding the ethical conduct of the study and supports the interpretation of experimental results obtained from the rats subjected to CFA-induced inflammation.

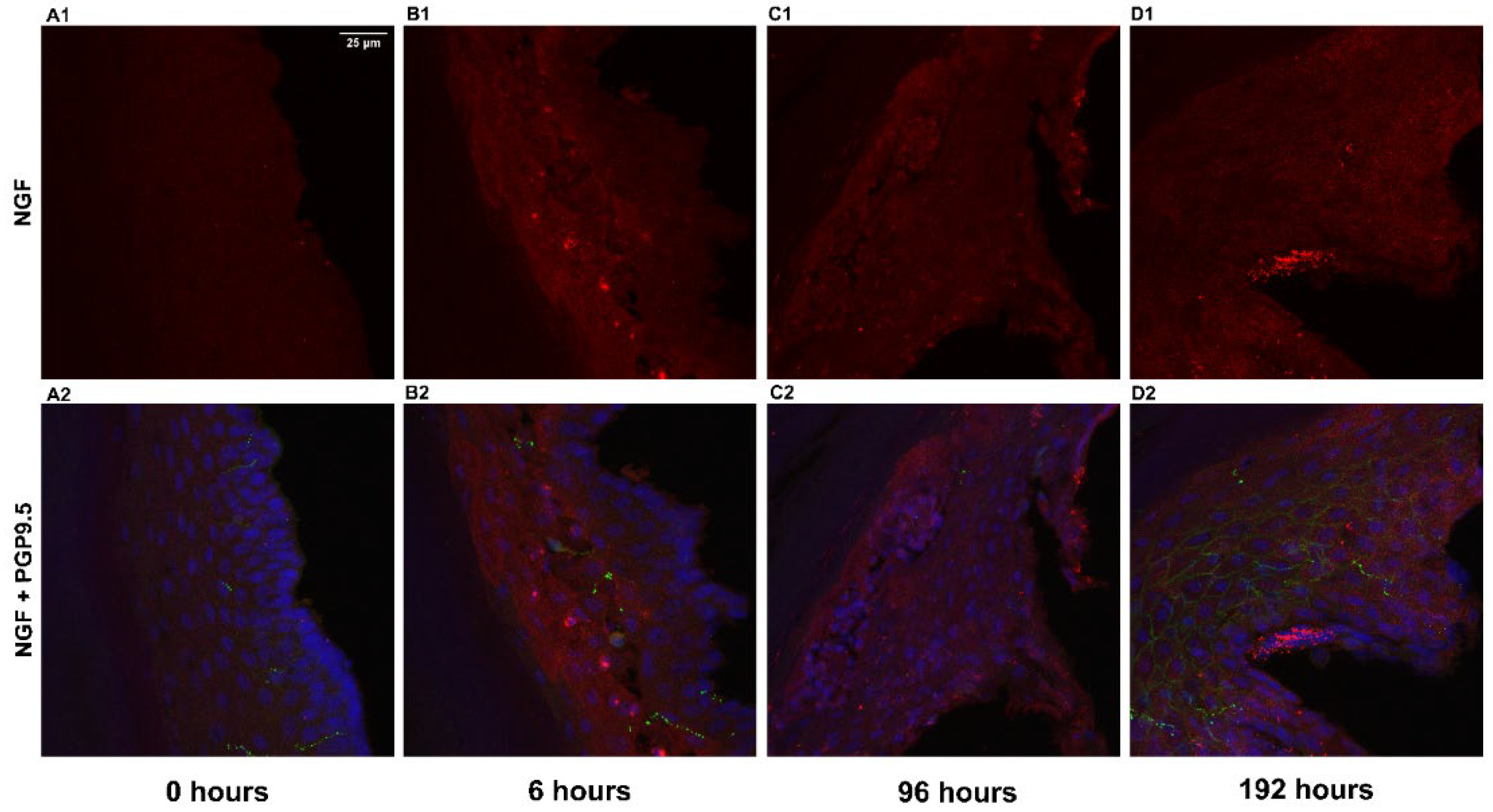

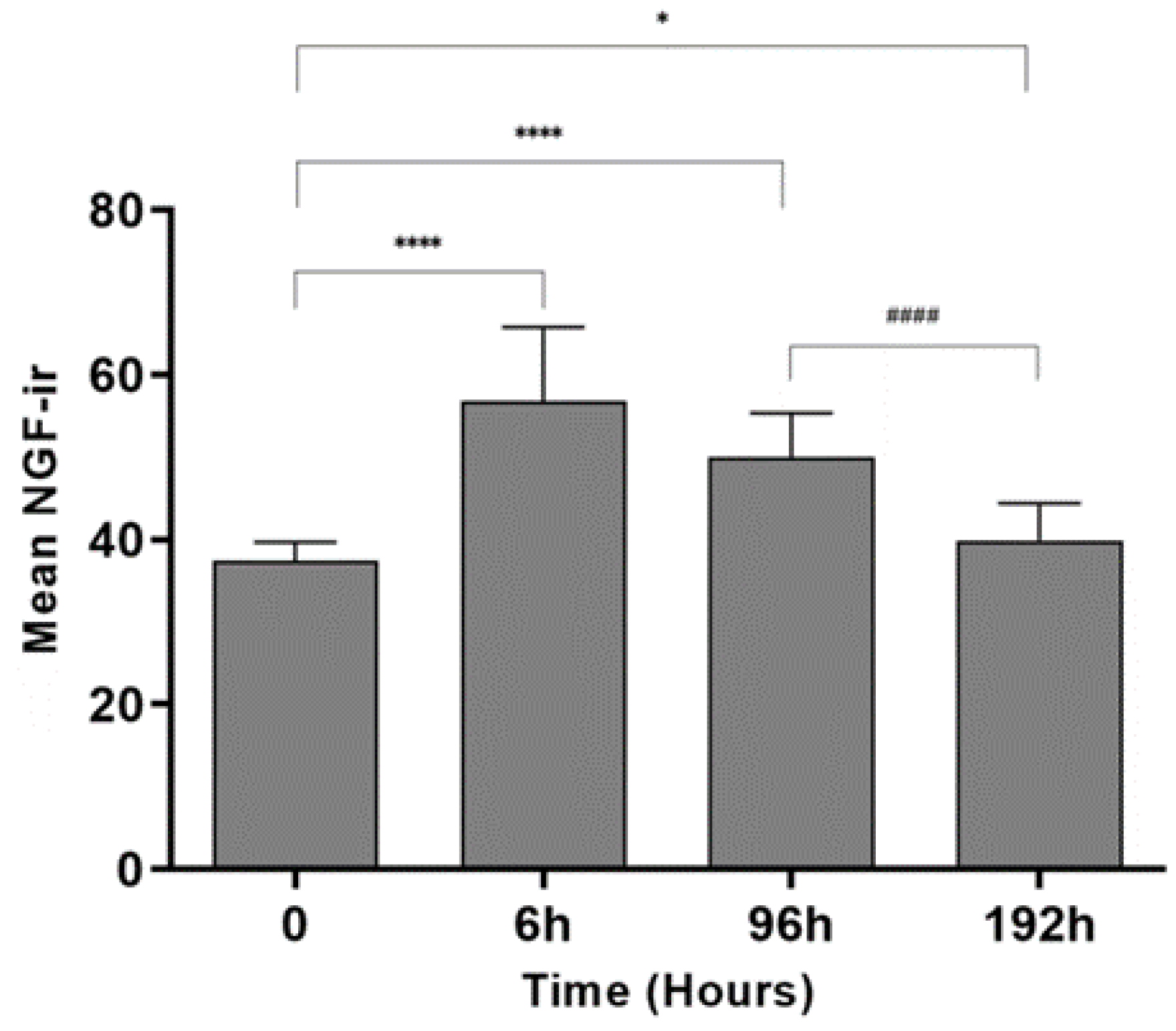

2.2. Change in NGF-Immunoreactivity (-ir) during Inflammation

For determining the levels of NGF protein, double labeling of NGF and PGP9.5 was performed on epidermal sections of the rat hind paw, and DAPI was used for nuclear staining. The images (

Figure 2.) indicate that the immunoreactivity of NGF after 6 hrs and 96 hrs of inflammation was comparatively higher than the control animals. The results from quantitative image analysis (

Figure 3.) indicate that the NGF immunoreactivity was considerably higher after 6 hrs of inflammation (p < 0.0001) with respect to the control sample (0 hrs). The immunoreactivity was reduced after 24 hrs but increased significantly after 96 hrs of treatment (p < 0.0001) and further decreased after 192 hrs (p = 0.036) compared to 0 hrs indicating a biphasic response. After 192 hrs, the immunoreactivity was found to be lower as compared to the 96 hrs sample (p < 0.0001). PGP 9.5 immunoreactivity in intraepidermal nerve fibers was qualitatively similar at all time points, similar to the results in our other studies [

13,

14].

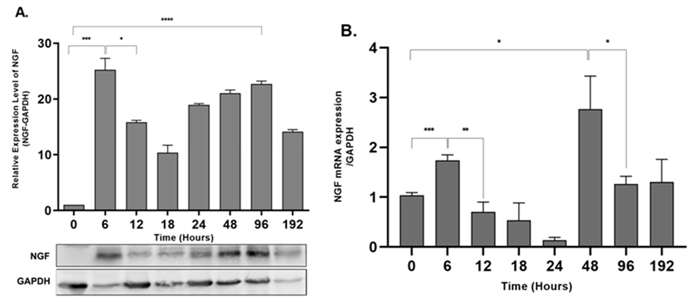

2.3. NGF Expression Shows Biphasic Response during Peripheral Inflammation

To evaluate the effect of progressive peripheral inflammation on NGF expression in rat epidermis, we determined the expression of NGF protein and mRNA by western blot analysis and qPCR, respectively. Levels of NGF mRNA were significantly upregulated after 6 hours of AIA (p = 0.0007), with a decrease after 24 hours and a second spike after 48 hours (p = 0.0109) (Figure 4B). The NGF protein level showed a similar biphasic response with two peaks after 6 hours (p = 0.0003) and 96 hours (p <0.0001) of peripheral inflammation compared with control animals (0 hours) (Figure 4A).

3. Discussion

The unilateral AIA caused a significant increase in the metatarsal thickness of the ipsilateral hind paws indicating a robust inflammatory process, as reported previously [

15,

16]. The injection of CFA induces the release of several inflammatory mediators leading to peripheral and central sensitization [

17], confirming that the AIA rat model is appropriate for studying the process of acute and chronic inflammatory process [

18]. The present study corroborates the contribution of NGF in developing and maintaining peripheral inflammation. We found that the levels of NGF protein were significantly upregulated after six hours of noxious stimulus and decreased after twenty-four hours. The levels again increased after ninety-six hours, showing a biphasic response.

As inflammation is converted from acute to chronic, it maintains its distinct characteristics, such as increased vascular permeability, vasodilation, and macrophage migration [

19]. After the initiation of inflammation in the periphery, both central and peripheral nervous systems exhibit significant changes that lead to altered sensory inputs and processing, for instance, enhanced excitability of primary afferent neurons [

20]. Skin, especially the epidermis, is densely innervated by specialized nerve endings of sensory afferent neurons that express and release neuropeptides. SP and CGRP-specific receptors are located on the epidermal keratinocytes and during inflammation, SP can stimulate epidermal keratinocytes to produce and release neurotrophins and inflammatory mediators like NGF and interleukin-1β respectively [

21,

22,

23,

24].

In this study we also confirmed that the mRNA levels of NGF are mirrored with that of the protein levels, showing two peaks. Previous work has shown the instant surge in NGF protein and mRNA levels in different inflammatory models of formalin, Complete Freund’s Adjuvant, carrageenan, and turpentine oil [

2,

4,

25,

26]. The primary source of NGF is attributed to specific inflammatory cells like mast cells [

27], macrophages [

28], lymphocytes, and eosinophils [

29], whereas the source in this study is indicative of epidermal keratinocytes. This modulation of NGF expression during peripheral damage is likely mediated by either neuropeptide released from cutaneous nerves or cytokines typically involved in tissue damage like IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Intraepidermal nerve fibers labeled with PGP 9.5 were consistent across the temporal course of AIA, indicating their potential for promoting and responding to inflammation and their presumptive uptake of the elevated NGF.

The immunohistochemical image analysis and Western blotting showed the two peaks of NGF protein, but there is a disparity in the percent change levels (Immunohistochemical image analysis; 6h – 15%, 96h – 10% and Western blotting; 6h – 30%, 96h – 25% approx.). These variations may exist due to the change in the protein conformation and target accessibility in immunohistochemistry compared to Western blotting (Uhlen et al., 2016). Although the NGF antibody (E-12) produced by Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. has specificity for both the mature (13kDa) and pro-NGF (27 and 35kDa) forms [

35], our Western blotting protocol was only able to detect the pro-forms, and we failed to demonstrate the lower molecular weight mature NGF forms. This might be due to the specific tissue processing, e.g., thermolysin separation, and Western blotting conditions we employed for this study. The pro-NGF is formed by the alternate splicing of the NGF gene, which is cleaved into a mature form [

36]. The Western blotting results are in agreement with the prior studies on the rat retina during optic nerve crush [

37]. We also observed variations in the percent change of mRNA levels compared to the protein levels. These changes may result from the change in expression levels of the housekeeping gene, which could be due to variations in biological conditions or differences in specific experimental conditions [

38,

39]. Considering this, we tested several housekeeping genes like β-actin, GAPDH, and 18s rRNA gene and found that the mRNA expression of GAPDH has the minimum variation (data not shown) in the skin of control and AIA rats.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

The research utilized Sprague-Dawley rats that were bred on-site and weighed between 250-350g. The rats were exposed to a 12-hour cycle of light and dark and had free access to food and water. The study was carried out at the Oklahoma State University-Centre for Health Sciences (OSU-CHS) with the full consent of the OSU-CHS Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol Number 2020/01). All steps were taken to limit the number of animals used in the experiments.

4.2. Induction of Adjuvant-Induced Arthritis (AIA)

Unilateral hind paw inflammation was induced in rats using Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA; Millipore Sigma). The rats were given isoflurane anaesthesia (initially 5%, then lowered to 2.5%) and then injected with 150 µl of a 1:1 CFA emulsion in 1X phosphate buffer saline into the underside of the rats’ hind paw. Control animals underwent the same anaesthesia procedure but did not receive the injection since PBS injection creates a minor local inflammation in the skin [

16]. The inflammation persisted for 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, and 192 hours, and the skin was harvested for analysis after euthanization by CO2 asphyxiation at each time point.

4.3. Hind Paw Edema and Body Weight

Metatarsal thickness was used to evaluate the severity of the inflammation in animals. The thickness of the rats’ hind paw on the same side as the inflammation was measured using a dial caliper (Mitutoyo, Japan) to the nearest 0.05 mm at each time point prior to tissue collection. The bodyweight of each animal was also measured using an electronic balance to monitor any significant changes due to ongoing inflammation [

40].

4.4. Thermolysin Treatment

Skin samples were processed for the epidermal-dermal separation as described previously [

14]. Briefly, the skin sample was collected after each time point in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Millipore Sigma) on ice. The skin tissues were transferred in a 0.5 mg/ml thermolysin solution (Millipore Sigma) and kept at 4°C for 2 hrs. After the incubation, the stratum corneum and the epidermis were separated from the dermis, then immersed in 5mM EDTA in DMEM for 30 min to stop the thermolysin activity. Following the proteolytic treatment, the epidermal sections were used for RNA and protein analysis.

4.5. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The IHC was performed as describes previously [

14,

41,

42]. Briefly, after treating the skin samples with thermolysin, the epidermal layer of the skin was submerged in a solution of 0.96% (w/v) picric acid and 0.2% (w/v) formaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.3. This immersion lasted for three hours at 4°C. The tissues were then transferred to a solution of 10% sucrose in PBS at pH 7.3 and kept overnight at 4°C. The vertical embedding of the epidermal section of the skin was performed in a frozen block, and the resulting block was sliced into 14 μm sections using a Leica CM 1850 cryostat. Each slide was then coated with gelatin and had three sections mounted onto it. Five slides were dried for one hour at 37°C at each time point. The dried sections were rinsed with PBS three times for 10 minutes each. Primary antibodies, anti-Nerve Growth Factor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a 1:1000 dilution and anti-PGP9.5 (Cedarlane Labs) at a 1:10,000 dilution, were then incubated with the frozen sections for four days at 4°C. After primary antibody incubation, the sections were rinsed three times with PBS and then incubated with anti-mouse Alexa Flour 555 and anti-rabbit FITC 488 for 60 minutes at room temperature in a dark box. The sections were then rinsed with PBS once and incubated with 300 nM 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) diluted in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature. After removing the DAPI, the sections were rinsed with PBS three times and mounted using ProLong Gold Mounting Media (Invitrogen).

4.6. Quantitative Image Analysis

The Leica DMI 4000B confocal microscope with a 40X objective was used to capture images. Sequential merging of 3-10 confocal images was performed to obtain the final images that represented the field of view. The resultant micrographs were saved in an 8-bit grayscale tiff format with a pixel intensity range of 0-255. Three filters, FITC, TRITC, and DAPI, were used to detect each fluorophore for each field of view from each epidermal section. An area of 7392 μm2 was selected as a fixed box to choose the epidermal region of interest (ROI) for each image. ImageJ software was used for analyzing all images. The ROI manager was used to select and add all the ROIs for a given image. Area and mean gray values were then measured and exported for further statistical analysis [

16].

4.7. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

The epidermal tissue of naïve and treated rats at various time points after CFA injection was used to isolate and purify total RNA using Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The M-MLV Reverse transcriptase (Promega) was employed to perform complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out using the ABI StepOneTM system from Applied Biosystems. To detect NGF mRNA, SYBR Select Master Mix from Thermo Fisher Scientific, was utilized, and GAPDH RNA was used as an internal reference for NGF. The primer sequences used for NGF and GAPDH are presented in

Table 1.

The PCR analysis results were reported as the threshold cycle (Ct), which determined the mRNA of the target gene in relation to the reference gene. The difference between the number of cycles required to detect the PCR products for the target and reference genes was represented by ΔCt. ΔΔCt, was the difference between the naïve animal group and the AIA group. Finally, the relative amount of target mRNA in the CFA-treated sample compared to the control animal group was expressed as 2-ΔΔCt.

4.8. Western Blot Analysis

After the thermolysin treatment, the epidermal tissue was homogenized with lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Millipore Sigma). Samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and total protein concentration was evaluated using Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples (50 µg/ml of total Protein) suspended in 10mM Tris Base, 1mM EDTA, 2.5% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.01% bromophenol blue were heat denatured at 100 °C for 10 min. Samples were separated using 12% TGX™ FastCast™ gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories) using the Mini Trans-Blot Cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The membranes were then blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline at room temperature, followed by rinsing with TBST. Overnight incubation at 4 °C with NGF antibody (E-12, Santa Cruz) at a 1:1000 dilution in TBST/5% milk was performed. The membranes were washed with TBST and then incubated in secondary alkaline phosphatase labelled anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG (Promega) at a 1:1000 dilution for 120 min. The details of the antibody used for western blot is provided in

Table 2. Western blot images were obtained using the ECF substrate on a Typhoon 9410 Variable Mode Imager. Image analysis was conducted using ImageJ (National Institute of Health).

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Student t-test was performed on all data sets using GraphPad Prism (version 9, GraphPad Prism). P values less than 0.05 were considered significant for all tests. The data presented in the graph are group mean + SEM (and/or SD).

5. Conclusions

In Summary, the present result indicates that the biphasic increase in the expression of NGF occurs after 6h and 96h, hence playing a vital role in the phasic progression of the inflammation. This temporal change in NGF expression during peripheral inflammation may help determine the timing of therapeutic interventions like anti-NGF antibodies for treating diseases like osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Chronic inflammatory conditions in humans can undergo amplified active and preclinical or quiescent stages [

43,

44,

45,

46], and effective anti-NGF therapy may require specific temporal dosing’s. Further studies will be required to assess the NGF levels during chronic inflammation to fully understand the role of NGF signalling during peripheral sensitization and determine the novel therapeutic targets.

Author Contributions

V.G.: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. R.D.P.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. S.D.: Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Review & Editing.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by the National Institute of Health, grant number NIH-AR047410” awarded to Dr. Kenneth E. Miller.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR HEALTH SCIENCE (74107 – 01/2020) Protocol Number 2020/01.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data is included in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the late Dr. Kenneth E Miller for his invaluable contributions to this project. Dr. Miller provided essential funding, guidance, and equipment support, which significantly facilitated our research endeavors. His dedication to advancing scientific knowledge and his unwavering support will always be remembered.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest with regard to the work.

References

- Denk, F.; Bennett, D.L.; McMahon, S.B. Nerve Growth Factor and Pain Mechanisms. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2017, 40, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, C.J.; Safieh-Garabedian, B.; Ma, Q.P.; Crilly, P.; Winter, J. Nerve growth factor contributes to the generation of inflammatory sensory hypersensitivity. Neuroscience. 1994, 62, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganju, P.; O’Bryan, J.P.; Der, C.; Winter, J.; James, I.F. Differential regulation of SHC proteins by nerve growth factor in sensory neurons and PC12 cells. Eur J Neurosci. 1998, 10, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizumura, K.; Murase, S. Role of nerve growth factor in pain. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015, 227, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Sheikh, Z.; Ahmed, A.S. Nociception and role of immune system in pain. Acta Neurol Belg. 2015, 115, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzer, P.; Maggi, C.A. Dissociation of dorsal root ganglion neurons into afferent and efferent-like neurons. Neuroscience. 1998, 86, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chiu, I.M.; von Hehn, C.A.; Woolf, C.J. Neurogenic inflammation and the peripheral nervous system in host defense and immunopathology. Nat Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J.J.; Allen, S.J.; Dawbarn, D. Targeting nerve growth factor in pain: what is the therapeutic potential? BioDrugs: clinical immunotherapeutics, biopharmaceuticals and gene therapy. 2008/11/13 ed. 2008, 22, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E.; Hoffman, E.M.; Sutharshan, M.; Schechter, R. Glutamate pharmacology and metabolism in peripheral primary afferents: physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther. 2011, 130, 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, A.W.; Ginty, D.D. Long-distance retrograde neurotrophic factor signalling in neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013, 14, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Lehigh, K.M.; Ginty, D.D. Multivesicular bodies mediate long-range retrograde NGF-TrkA signaling. Elife [Internet]. 2018,7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29381137. [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Guo, T.Z.; Li, W.W.; Hou, S.; Kingery, W.S.; Clark, J.D. Keratinocyte expression of inflammatory mediators plays a crucial role in substance P-induced acute and chronic pain. J Neuroinflammation. 2012, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson MB Miller, KE, Schechter, R. Evaluation of rat epidermis and dermis following thermolysin separation: PGP 9.5 and Nav 1.8 localization. In 2010.

- Gujar, V.; Anderson, M.B.; Miller, K.E.; Pande, R.D.; Nawani, P.; Das, S. Separation of Rat Epidermis and Dermis with Thermolysin to Detect Site-Specific Inflammatory mRNA and Protein. J Vis Exp [Internet]. 2021/10/19 ed. 2021,(175). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34661580. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.M. The role of dorsal root ganglion glutaminase in nociception - A novel therapeutic target for inflammatory pain [Ph.D.]. Vol. 3356494. [Ann Arbor]: Oklahoma State University; 2009. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. The role of dorsal root ganglion glutaminase in acute and chronic inflammatory pain [Internet] [Ph.D.]. Vol. 3629945. [Ann Arbor]: Oklahoma State University; 2013. Available from: http://argo.library.okstate.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1562918358?accountid=4117.

- Ji, R.R.; Xu, Z.Z.; Gao, Y.J. Emerging targets in neuroinflammation-driven chronic pain. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014/06/21 ed. 2014, 13, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burma, N.E.; Leduc-Pessah, H.; Fan, C.Y.; Trang, T. Animal models of chronic pain: Advances and challenges for clinical translation. J Neurosci Res. 2016/07/05 ed. 2017, 95, 1242–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahwa, R.; Jialal, I. Chronic Inflammation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL); 2018. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29630225.

- Lamb, K.; Zhong, F.; Gebhart, G.F.; Bielefeldt, K. Experimental colitis in mice and sensitization of converging visceral and somatic afferent pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006, 290, G451–G457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbins, I.L.; Wattchow, D.; Coventry, B. Two immunohistochemically identified populations of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-immunoreactive axons in human skin. Brain Res. 1987/06/23 ed. 1987, 414, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemeny, L.; von Restorff, B.; Michel, G.; Ruzicka, T. Specific binding and lack of growth-promoting activity of substance P in cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1994/10/01 ed. 1994, 103, 605–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wang, L.; Clark, J.D.; Kingery, W.S. Keratinocytes express cytokines and nerve growth factor in response to neuropeptide activation of the ERK1/2 and JNK MAPK transcription pathways. Regul Pept. 2013, 186, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viac, J.; Gueniche, A.; Doutremepuich, J.D.; Reichert, U.; Claudy, A.; Schmitt, D. Substance P and keratinocyte activation markers: an in vitro approach. Arch Dermatol Res. 1996/02/01 ed. 1996, 288, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.B.; Bennett, D.L.; Priestley, J.V.; Shelton, D.L. The biological effects of endogenous nerve growth factor on adult sensory neurons revealed by a trkA-IgG fusion molecule. Nat Med. 1995/08/01 ed. 1995, 1, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddiah, D.; Anand, P.; McMahon, S.B.; Rattray, M. Rapid increase of NGF, BDNF and NT-3 mRNAs in inflamed bladder. Neuroreport. 1998/06/19 ed. 1998, 9, 1455–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon A, Buriani A, Dal Toso R, Fabris M, Romanello S, Aloe L, et al. Mast cells synthesize, store, and release nerve growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994/04/26 ed. 1994, 91, 3739–3743. [CrossRef]

- Heumann R, Lindholm D, Bandtlow C, Meyer M, Radeke MJ, Misko TP, et al. Differential regulation of mRNA encoding nerve growth factor and its receptor in rat sciatic nerve during development, degeneration, and regeneration: role of macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987/12/01 ed. 1987, 84, 8735–8739. [CrossRef]

- Mantyh, P.W.; Koltzenburg, M.; Mendell, L.M.; Tive, L.; Shelton, D.L. Antagonism of nerve growth factor-TrkA signaling and the relief of pain. Anesthesiology. 2011, 115, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallos, A.; Kiss, M.; Polyanka, H.; Dobozy, A.; Kemeny, L.; Husz, S. Effects of the neuropeptides substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and galanin on the production of nerve growth factor and inflammatory cytokines in cultured human keratinocytes. Neuropeptides. 2006, 40, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, D.; Heumann, R.; Meyer, M.; Thoenen, H. Interleukin-1 regulates synthesis of nerve growth factor in non-neuronal cells of rat sciatic nerve. Nature. 1987/12/17 ed. 1987, 330, 658–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marz, P.; Heese, K.; Dimitriades-Schmutz, B.; Rose-John, S.; Otten, U. Role of interleukin-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor in region-specific induction of astrocytic differentiation and neurotrophin expression. Glia. 1999/05/26 ed. 1999, 26, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safieh-Garabedian, B.; Poole, S.; Allchorne, A.; Winter, J.; Woolf, C.J. Contribution of interleukin-1 beta to the inflammation-induced increase in nerve growth factor levels and inflammatory hyperalgesia. Br J Pharmacol. 1995/08/01 ed. 1995, 115, 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, C.J.; Allchorne, A.; Safieh-Garabedian, B.; Poole, S. Cytokines, nerve growth factor and inflammatory hyperalgesia: the contribution of tumour necrosis factor alpha. Br J Pharmacol. 1997/06/01 ed. 1997, 121, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, R.H.; Selby, M.J.; Garcia, P.D.; Rutter, W.J. Processing of the native nerve growth factor precursor to form biologically active nerve growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1988/05/15 ed. 1988, 263, 6810–6815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidah NG, Benjannet S, Pareek S, Savaria D, Hamelin J, Goulet B, et al. Cellular processing of the nerve growth factor precursor by the mammalian pro-protein convertases. Biochem J. 1996/03/15 ed. 1996,314 ( Pt 3):951–60. [CrossRef]

- Mesentier-Louro LA, De Nicolo S, Rosso P, De Vitis LA, Castoldi V, Leocani L, et al. Time-Dependent Nerve Growth Factor Signaling Changes in the Rat Retina During Optic Nerve Crush-Induced Degeneration of Retinal Ganglion Cells. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2017/01/10 ed. 2017,18(1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28067793. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shen, Y. An old method facing a new challenge: re-visiting housekeeping proteins as internal reference control for neuroscience research. Life Sci. 2013/03/05 ed. 2013, 92, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turabelidze, A.; Guo, S.; DiPietro, L.A. Importance of housekeeping gene selection for accurate reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction in a wound healing model. Wound Repair Regen. 2010/08/25 ed. 2010, 18, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujar, V. Understanding the Mechanism of Nerve Growth Factor Signaling during Peripheral Inflammation [Internet] [Ph.D.]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. [United States -- Oklahoma]: Oklahoma State University; 2020. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/understanding-mechanism-nerve-growth-factor/docview/2572613459/se-2?accountid=45198.

- Hoffman, E.M.; Schechter, R.; Miller, K.E. Fixative composition alters distributions of immunoreactivity for glutaminase and two markers of nociceptive neurons, Nav1.8 and TRPV1, in the rat dorsal root ganglion. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010, 58, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, E.M.; Zhang, Z.; Anderson, M.B.; Schechter, R.; Miller, K.E. Potential mechanisms for hypoalgesia induced by anti-nerve growth factor immunoglobulin are identified using autoimmune nerve growth factor deprivation. Neuroscience. 2011, 193, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezuidenhout, J.A.; Pretorius, E. The Central Role of Acute Phase Proteins in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Involvement in Disease Autoimmunity, Inflammatory Responses, and the Heightened Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2020/05/22 ed. 2020, 46, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti F, Ceccarelli F, Perricone C, Miranda F, Truglia S, Massaro L, et al. Flare, persistently active disease, and serologically active clinically quiescent disease in systemic lupus erythematosus: a 2-year follow-up study. PLoS One. 2012/10/03 ed. 2012, 7, e45934. [CrossRef]

- Helmchen, B.; Weckauf, H.; Ehemann, V.; Wittmann, I.; Meyer-Scholten, C.; Berger, I. Expression pattern of cell cycle-related gene products in synovial stroma and synovial lining in active and quiescent stages of rheumatoid arthritis. Histol Histopathol. 2005/03/01 ed. 2005, 20, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenink MH, Santegoets KC, Roelofs MF, Huijbens R, Koenen HJ, van Beek R, et al. The inhibitory Fc gamma IIb receptor dampens TLR4-mediated immune responses and is selectively up-regulated on dendritic cells from rheumatoid arthritis patients with quiescent disease. J Immunol. 2009/09/08 ed. 2009, 183, 4509–4520. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).