1. Introduction

In today’s digital era, understanding the underlying feelings and potential biases within these reviews has become critical, when online reviews and user-generated material have significant impact over customer decisions. Sentiment analysis, also known as opinion mining, is the computational analysis of people's views, feelings, emotions, and attitudes about entities such as products, services, issues, events, ideas, and their attributes [

1]. As opinions and sentiments are widely expressed on many platforms ranging from e-commerce websites to social media, the necessity for accurate sentiment analysis technologies that not only recognize emotions but also detect potential biases has become critical, thus improving reviews’ usefulness.

Analysing the pertinent literature, it can be inferred that sentiment analysis is a rich area for research across various fields, such as e-business, e-learning, marketing, social networking sites, customer feedback, political discourse, etc.

Firstly, in the area of e-business, it has been used to assess the sentiments of customers and receive their preference on either products or services [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Indeed, online commerce platforms can have availability of a large pool of data in the form of customer feedback or reviews that can serve as a valuable source of information towards building their promotion strategy. As such, companies apply sentiment analysis techniques on this data to gain important insights on customer satisfaction and take corresponding decisions to improve customer experience. A recent review on sentiment analysis in e-business attests that sentiment analysis has been widely used in e-commerce using mainly machine learning algorithms.

In the context of e-learning, sentiment analysis finds application in analysing students' feedback on learning objects, forum discussions, and course evaluations [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. This process yields valuable insights into learners' emotions and sentiments, enabling the creation of personalized learning experiences. By understanding students' feelings, educators can deliver tailored learning materials, exercises, and collaborative opportunities. Moreover, sentiment analysis serves as a valuable tool for identifying areas of improvement in the e-learning environment, helping educators enhance the overall learning experience. A recent review work of 2023 [

12] highlighted that sentiment analysis has shown to be effective for educators as it helped them improve their teaching methodology and tailor the course content to students. Also, concerning learners, sentiment analysis has helped them advance their knowledge and has provided them with access to qualitative learning.

Furthermore, sentiment analysis has also been widely used in social networking sites [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], since understanding the opinion of people holds significant implications. Researchers have developed domain-specific sentiment analysis techniques to tackle the unique challenges posed by noisy social media data. A review study of 2023 [

18] attests that sentiment analysis can have great implications in this field while the techniques used are mainly neural networks and Support Vector Machines (SVMs).

Also, sentiment analysis finds application in political discourse analysis [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], where analysing public sentiment towards political candidates, policies, and events can inform campaign strategies and policy decisions. By analysing sentiments expressed in political tweets, news articles, and online forums, valuable insights into public perceptions can be gained.

As shown in the aforementioned studies, two prevalent approaches have been used for sentiment analysis. The first approach is the lexicon-based techniques. The lexicon-based methods assign positive, negative, or neutral sentiment scores to individual words and then aggregate the scores to determine the overall sentiment of a text. While simple and easy to implement, lexicon-based methods suffer from limited context awareness and may struggle with sarcasm, idioms, or language nuances.

Machine learning approaches in sentiment analysis that can perform better in situations where lexicon-based techniques may present obstacles. Researchers have resorted to machine learning techniques such as supervised learning and deep learning to categorize text sentiments automatically. Supervised learning entails training models on labelled datasets where each text is assigned a sentiment label such as positive, negative, or neutral. These models learn to recognize patterns in the data that can be applied to new situations with similar sentiments. Among the popular supervised learning algorithms used in sentiment analysis are Support Vector Machines, Naive Bayes (NB), and Random Forests. These algorithms are adept at classifying sentiments based on the patterns they learn from the labelled training data.

Deep learning approaches, including Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have shown important effectiveness in sentiment analysis applications. RNNs perform well for sequential data and can capture long-term dependencies in text. CNNs are well-suited in learning local patterns and features from text. Moreover, the advent of pre-trained language models, such as BERT and GPT, has significantly advanced sentiment analysis, as these models can have great performance on specific sentiment analysis tasks.

In conclusion, a recent review by [

24]highlights the extensive application of sentiment analysis, with social networks being the predominant field of use. The techniques predominantly employed in sentiment analysis involve traditional machine learning approaches, particularly Support Vector Machines and Naive Bayes.

Moreover, fuzzy logic, with its ability to model imprecise and uncertain information, provides a robust framework for identifying the sentiment of reviews and evaluating the potential bias that might be present in the expressions.

Although bias in sentiment analysis has attracted the attention of many researchers [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], sentiment analysis systems confront several challenges [

32]. The effectiveness of sentiment analysis methods depends on the bias embedded in documents, such as gender or nationality bias as well as on how well the method addresses the so called domain adaptation problem [

33].

Research studies suggest there is an urgent need to develop sentiment analysis techniques that can identify and quantify bias [

29,

32,

34]. Bias in reviews can be attributed among other, to personal characteristics such as gender or cultural differences [

27,

29,

35,

36]. However, a few studies focus on understanding the role of cultural differences in user content generation [

35,

36,

37]. This study proposes a FSE approach to calculate reviews’ usefulness by incorporating bias which is embedded in reviews of different nationalities users. This study considers reviews’ document and title sentiment, and articulacy as determinants of usefulness. Although fuzzy logic has been used in sentiment analysis, there is little-to-no research that utilises fuzzy logic to model and analyse usefulness and bias in sentiments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: 2. Literature review on reviews usefulness and reviewers’ bias; 3. Methodology; 4. Methods; 5. Results; 6. Limitations of the study and Future Research; and 7. Conclusions.

2. Reviews’ Usefulness and Reviewers’ Bias in Sentiment Analysis

A plethora of reviews have flooded the online platforms such as Tripadvisor, Booking, etc., since reviews have been recognised as an important source of information for customers [

38,

39]. As a result, when users need to focus on the most useful opinions, they encounter vast numbers of reviews that imply high search costs and information overload [

40,

41]. It is argued [

42,

43] that the adoption usefulness voting systems can benefit both consumers and businesses. Customers may find assistance to tackle the sheer numbers of reviews by focusing on the most appropriate reviews and businesses are expected to develop revenue streams. Thus, a major research question arises with respect to how consumers identify the useful reviews and how they perceive high-quality ones [

38,

39]. In the relevant literature the usefulness of reviews has been examined by two perspectives namely: the review and the reviewers’ related factors [

38]. Review related factors include length of review, sentiment extremity, novelty, depth, rating, and information inconsistency [

38,

39,

40,

41,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Reviewer related factors include expertise, experience, identity, rank and reputation [

46,

51]. It is also argued that since users read lots of reviews, the usefulness of a review does not solely rely on the reviews’ characteristics, but also on the characteristics of the reviews that have been read previously by the user as well as on the products context factors such as product satisfaction, product popularity, intangibility, etc. [

38]. However, research studies reach contradicting results [

38]. Some studies argue that consumers prefer reviews with depth, i.e. more words in a review [

42,

52]. Other studies argue that there is no significant relationship between review depth and usefulness [

46,

53]. It is argued that if a review’s length exceeds a certain threshold, then its readability diminishes as it would require consumer to spend more time to read it [

53]. However, is such a threshold the same for all reviewers? In the same vein, studies indicate that reviews’ sentiment extremity, has a positive effect on usefulness [

41,

50], others report a negative effect [

44,

50], while other results show no effect at all [

43,

52,

53]. The question that arises is if the same extremes are perceived similarly by all reviewers. Of ‘course, not all users express themselves or perceive reviews extremes the same way. Therefore, despite the undeniable value of reviews and sentiment analysis applications, biases in users’ reviews which are often overlooked may subsequently result to misleading and often contradicting judgements. Indeed, several research studies focused on investigating bias in sentiment analysis [

30,

31]. The association of certain words and expressions with males or females as an indicator of gender bias, is examined in [

29]. Results indicate that women tend to use more direct language than males, to express either positive or negative sentiments. Research findings suggest that there are gender differences regarding the extent to which sentiments are expressed in user reviews [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Gender bias is also found in political writing [

34]. Sentiment analysis results indicate that sentiment is less positive when a political article refers to a female figure than a male. Behavioural differences were also discussed in [

54], where tweets were analysed and a method for gender identification was proposed.

Differences on sentiments can also be attributed to different nationalities. Users’ cultural background implies that they may have different priorities or they may seek information from different sources. Customers from Greece and Portugal prefer to rely on word of mouth rather than commercial marketing sources which are the choice of the customers from the UK and USA [

36]. Users from the USA tend to appreciate reviews’ evaluations from their compatriots more than those from other countries [

35]. Asian hotel visitors exhibit different complaint behaviour, since they seem to rather refrain themselves for expressing their complaints publicly compared to the non-Asian visitors [

37]. A research study [

35] indicates that guests from western countries usually express their feelings in a more positive and informative way than others. Visitors’ nationality is also identified as a discriminator factor since statistically significant differences were found in sentiments expressed by people from America, Europe, Middle East, and Asia [

55].

3. Methodology

This study proposes methodology that utilises fuzzy logic in order to assess reviews usefulness by incorporating cultural differences and biases embedded in user reviews, thus increasing reviews’ readability by recommending the most appropriate reviews to users according to their preferences. This study approaches cultural differences in terms of reviews’ sentiments and articulacy since relevant research has identified both as determinants of reviews’ usefulness [

47,

49]. Thus, it aims to:

Analyse reviews and to investigate how lenient users of different nationalities are in their reviews when expressing their sentiments.

To assess any differences in the way users, express themselves, i.e. to contrast sentiments polarity and strength in their reviews’ title and full bodies.

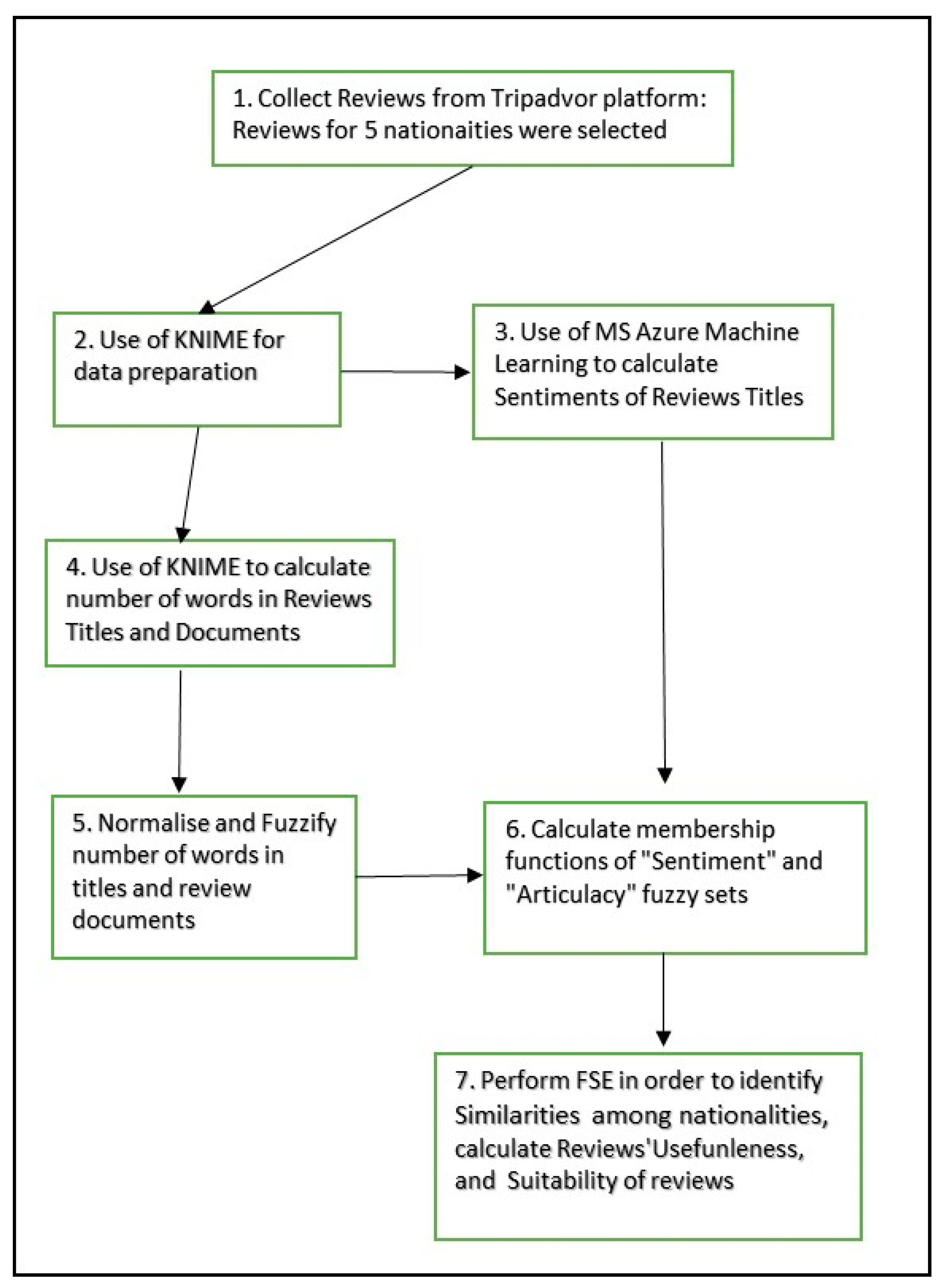

Figure 1.

The steps of the proposed methodology.

Figure 1.

The steps of the proposed methodology.

This study collected hotel reviews from Tripadvisor over the years 2020-2022 using open source web crawler Python Scrapy. Data included the review’s text, its title, and the nationality of the reviewer. In total, 95.678 reviews were selected for 5 nationalities namely: British, US, Australian, Greek and Dutch. The sample consists of 42.678 reviews from British citizens (44,6%), 40.311 from the USA (42,1%), 9.293 from Australians (9,7%), 1.734 from Dutch (1,8%) and 1.662 from Greek citizens (1,6%). The sample is clearly biased, since the majority of the reviews is selected from reviewers whose mother tongue is meant to be English. KNIME visual programming software platform was used for data preparation and analysis. KNIME is an open-source platform that provides tools to manipulate and prepare data and machine learning algorithms for data analysis. A node is the fundamental unit which performs tasks as, delete stop words, create a bag of words, calculate TF-IDF scores, train a neural network, etc. Nodes are combined through drag-and-drop to develop a workflow in KNIME. KNIME has been used in several studies such as in [

32,

56]. The collected dataset was initially cleaned, anonymized and pre-processed in order to be imported in KNIME as a CSV file. Subsequently the documents were checked for misspelling errors, they were converted in lower cases, stop words were removed and reviews’ texts were tokenized.

This study uses MS Azure Machine learning to calculate the sentiment strength and polarity for both the review’s document and its title. The sentiment strength returns values in the interval [0,1]. Values close to 0 indicate negative sentiment while values close to 1 indicate positive sentiment. The polarity is quantified with a positive, neutral, or negative value. The MS Azure sentiment analysis service is used in [

57] in order to calculate the sentiment of the mood that prevails in forum discussions regarding listed companies and include it in stock market data analysis. Jiang et al. (2022) [

58], assessed the effectiveness of MS Azure sentiment analysis service in conjunction with other sentiment analysis tools with metaphoric testing. In another study [

59], the MS Azure sentiment machine learning was used to calculate the sentiment and satisfaction expressed by patients regarding online doctor services.

4. Methods

This study represents sentiment and articulacy as triangular fuzzy number (TFN). TFNs are represented by triple (a, b, c). The membership function

of TFN

can be calculated according to the following equation [

60]

where a, b, c are real numbers.

4.1. Fuzzy Relations

Fuzzy relations are important for they can describe the strength of interactions between variables [

61,

62]. Fuzzy relations, which are fuzzy sets, are fuzzy subsets of

, that is mapping from

. Let

be universal sets. Then

is called a fuzzy relation on

[

62]. A fuzzy relation on a single universe

is also a relation from

to

. It is a fuzzy tolerance relation if the two following properties define it:

Reflexivity: and

Symmetry:

The resulting fuzzy relation is the tolerance matrix, which indicates the similarity degrees between related concepts.

The “usefulness” of reviews is calculated by applying fuzzy relation composition. The composition is implemented by the Cartesian product of two fuzzy sets. Assume fuzzy set

on universe

and

on universe

, then the Cartesian product will result in relation

, which is contained in the Cartesian product space so that

. The membership function of fuzzy relation

is calculated according to equation (3).

4.2. Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation

The Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation (FSE) has been widely used to assess muti-criteria problems [

63,

64,

65,

66]. The FSE conceptualizes a decision making problem at three levels: the indicators, the criteria, and the alternatives [

63,

64,

65]. It associates the three levels drawing on fuzzy relations. The steps of FSE follow:

- i)

Assume that is the set of criteria, and indicates criterion (i). This study assumes the criterion “usefulness” thus, .

- ii)

Assume is the set of indicators, where indicates indicator (j). It consists of the “title-sentiment (ts)”, “review-sentiment (rs)”, “title-articulacy (ta)” and the “review-articulacy (ra)” indicators thus, .

- iii)

is the set of assessment grades for criteria, indicators, and alternatives, with indicating assessment grades.

More specifically,

the set of assessment grades used for the criterion “usefulness” is, .

Respectively for the indicators,

, for

, which in our case are

All the above consist of three grades, therefore .

- iv)

is the set of the alternatives, where (z) is the number of reviews that are potentially considered by the users when seeking advice for a destination.

- v)

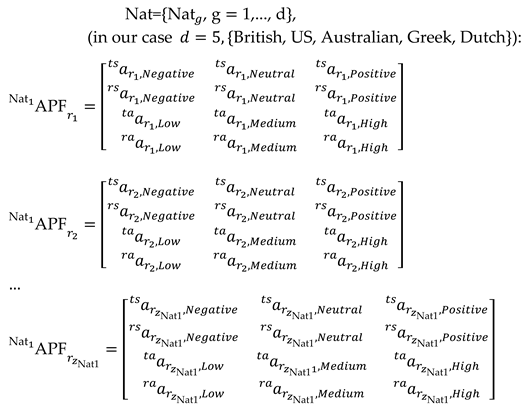

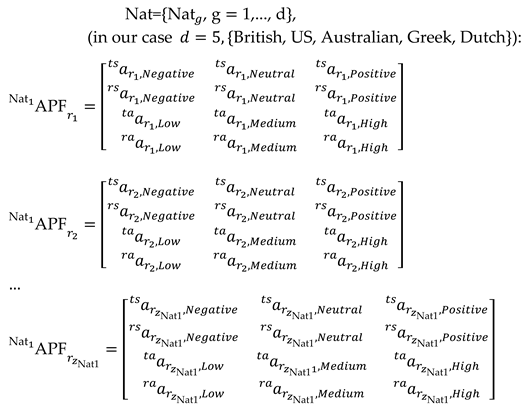

Establish the membership function matrix for each nationality ,

(in our case ):

|

(4) |

where indicates the membership degrees to which satisfies assessment grade , to the total of reviews (z).

For example, in order to calculate the membership degree to which indicator “title sentiment - ”, indicator, , satisfies assessment grade, , “Negative” (element (1,1) of the matrix above), we calculate the percentage of the total reviews that are related as “Negative”. Respectively, we calculate the percentage of the total reviews that are related as “Neutral” and “Positive”.

Let assume that the calculation returns that 17% of the British reviews are rated as “Negative”, 23% as “Neutral” and 60% as “Positive”; then the membership function of the “title-sentiment -

”, is given by (5):

Each of the three assessment grades is assigned to a rating factor

, e.g. Negative=1, Neutral=2, and Positive=3, and Low=1, Medium=2, and High=3, as used in other studies [

63,

64,

66,

67].

- vi)

Calculate the weights

for each indicator

. This study adopts the ordered weight averaging aggregation (OWA), which is often used in fuzzy logic [

63,

67]. The weights are calculated using the equations (6) and (7):

where

is the aggregated importance vector for indicator ,

is the rating factor given to assessment grade , and

m is the number of indicators under one criterion.

Therefore, the vector of weights for the (m) indicators is given by:

- vii)

Calculate the weights , for each criterion . The weights are calculated using the equation (9).

for all indicators under criterion

.

This study assumes one criterion, i.e. the “usefulness” of reviews.

- viii)

Establish the membership function matrix APF of the alternatives’ performance for each nationality

|

(10) |

indicates the membership degrees to which alternative satisfies assessment grade . This study considers the set of reviews that a user may consider as the set of alternatives.

- ix)

Aggregate performance evaluation for alternative

using fuzzy composition [

61,

63,

65]as shown in equation (11):

The three scalars of

, represent the membership degrees of each assessment grade

, for the alternative

, thus

A crisp value for

can be obtained after defuzzification. This study adopts the equations (15) and (16) used in [

63] in order to calculate the score for alternative

:

5. Results

5.1. Reviews’ Sentiments membership functions

Results indicate that the British exhibit more consistent behaviour with their sentiments expressed in reviews’ titles and bodies in all three sentiments categories than the other nationalities in the sample.

Table 1.

Title and Review sentiment percentages for each nationality in the sample.

Table 1.

Title and Review sentiment percentages for each nationality in the sample.

| |

Sentiment |

| Title |

Review |

Title |

Review |

Title |

Review |

| Negative |

Neutral |

Positive |

| British |

4,08 |

4,68 |

6,83 |

6,65 |

89,08 |

88,67 |

| USA |

4,73 |

32,21 |

5,89 |

7,10 |

89,37 |

60,67 |

| Australian |

2,60 |

28,74 |

6,46 |

6,40 |

90,94 |

64,86 |

| Greek |

3,55 |

6,26 |

6,68 |

24,13 |

89,77 |

69,61 |

| Dutch |

3,86 |

30,68 |

6,69 |

4,56 |

89,45 |

64,76 |

The sentiments British expressed in either their review’s titles or the reviews’ documents are almost identical. All nationalities in the sample are unanimous in expressing more positive than negative sentiments to a large extent, which is a good sign for the quality of the services reviewers received during their visits.

Differences range from a 20,16% more positive evaluations in titles than in full texts in the Greek sample, to a 28,7% in the USA sample. Similarly, more negative evaluations are found in full documents than in titles. Sentiment frequencies vary from a minimum of 2,71% more negatives in the full documents in the Greek sample, to the maximum of 27,48% in the USA sample. This implies that when the Greeks express negative sentiments in their titles, they do so more concisely and more accurately than the other three nationalities. For the Australians, and Dutch samples show larger percentage differences which are 26,14% and 26,82% respectively. With respect to neutral sentiments, percentage differences between titles and full reviews are rather small ranging from almost 0 to 2,13%, with the exception of the Greek sample (17,45%).

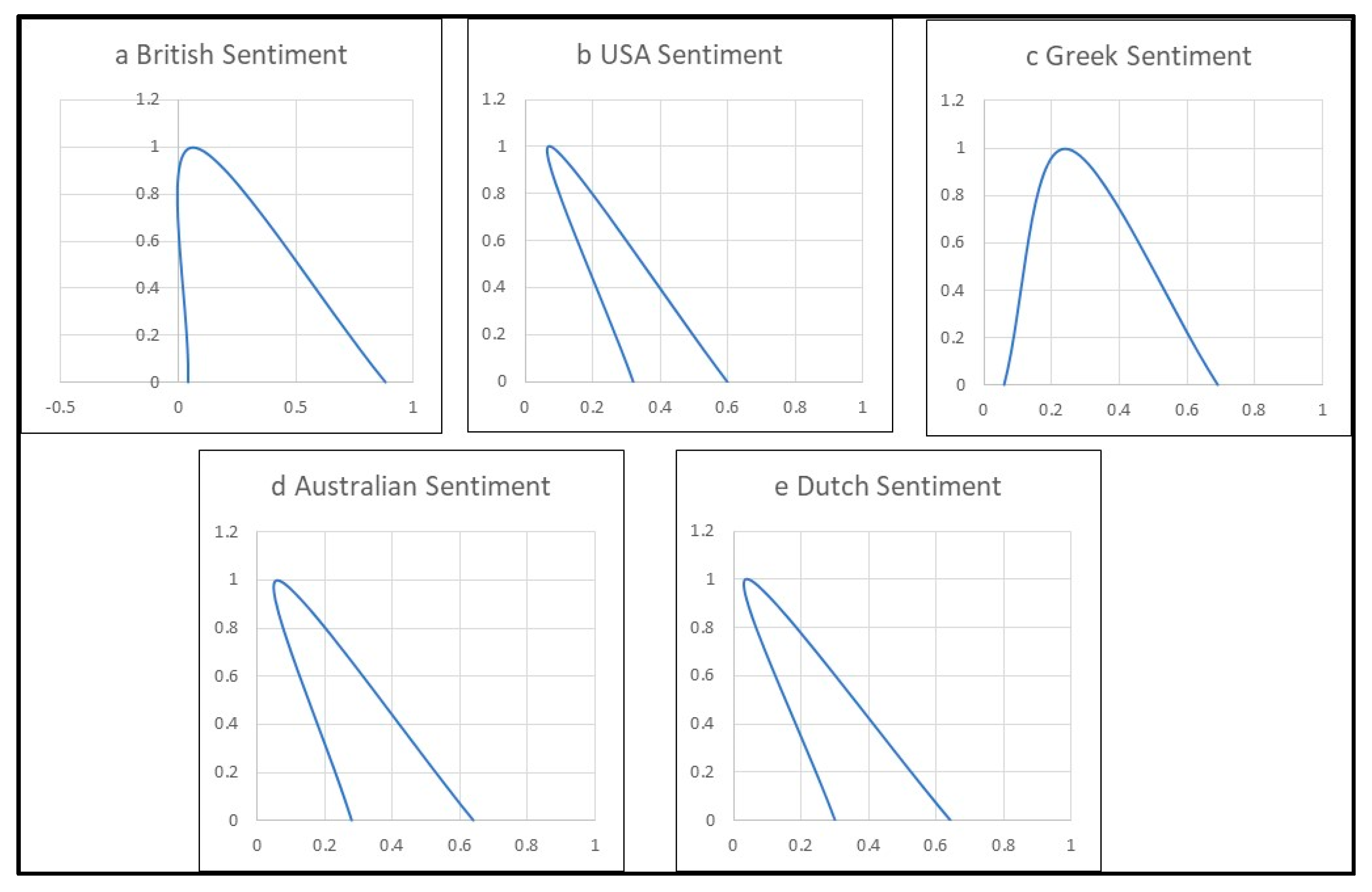

To accommodate the differences in users’ behaviour, this study proposes to represent sentiments from different nationalities as triangular fuzzy sets

. According to [

64,

66,

67], the membership function of each sentiment fuzzy set is formed as follows: In the sample of the total 42.678 British reviews, 1.742 expressed negative sentiment in their title, which returns a 4% negative reviews. Similarly, neutral titles account for a 6%, and positive ones for an 89%. Thus, for the British title sentiments the membership function is:

. The rating given to each assessment grade (i.e. Negative=1, Neutral=2, Positive=3), is adopted by [

63,

64,

66,

67]. The membership functions for both titles and reviews sentiments for each nationality, are shown in

Table 2.

Figure 2 clearly depicts the differences between the British and the USA reviews’ sentiment fuzzy sets, which imply the behavioural differences between the two nationalities.

The sentiments’ fuzzy sets with their membership functions show the level of “positiveness” in reviews for each nationality. The diagrams show that British and Greek reviewers are inclined towards more positive comments than the other nationalities in the sample. The USA, Australians and Dutch users’ sentiments are closer for both titles and reviews.

5.2. Reviews’ Articulacy membership functions

Table 3 shows the results regarding the articulacy of reviews by calculating the mean and standard deviation of both the titles and the full review for each nationality.

The normalisation of the number of words in titles and reviews is performed by applying equation (14),

where,

indicates the normalised values of the number of words in the title for nationality and review , and

, represents the original number of words in the title for nationality and review.

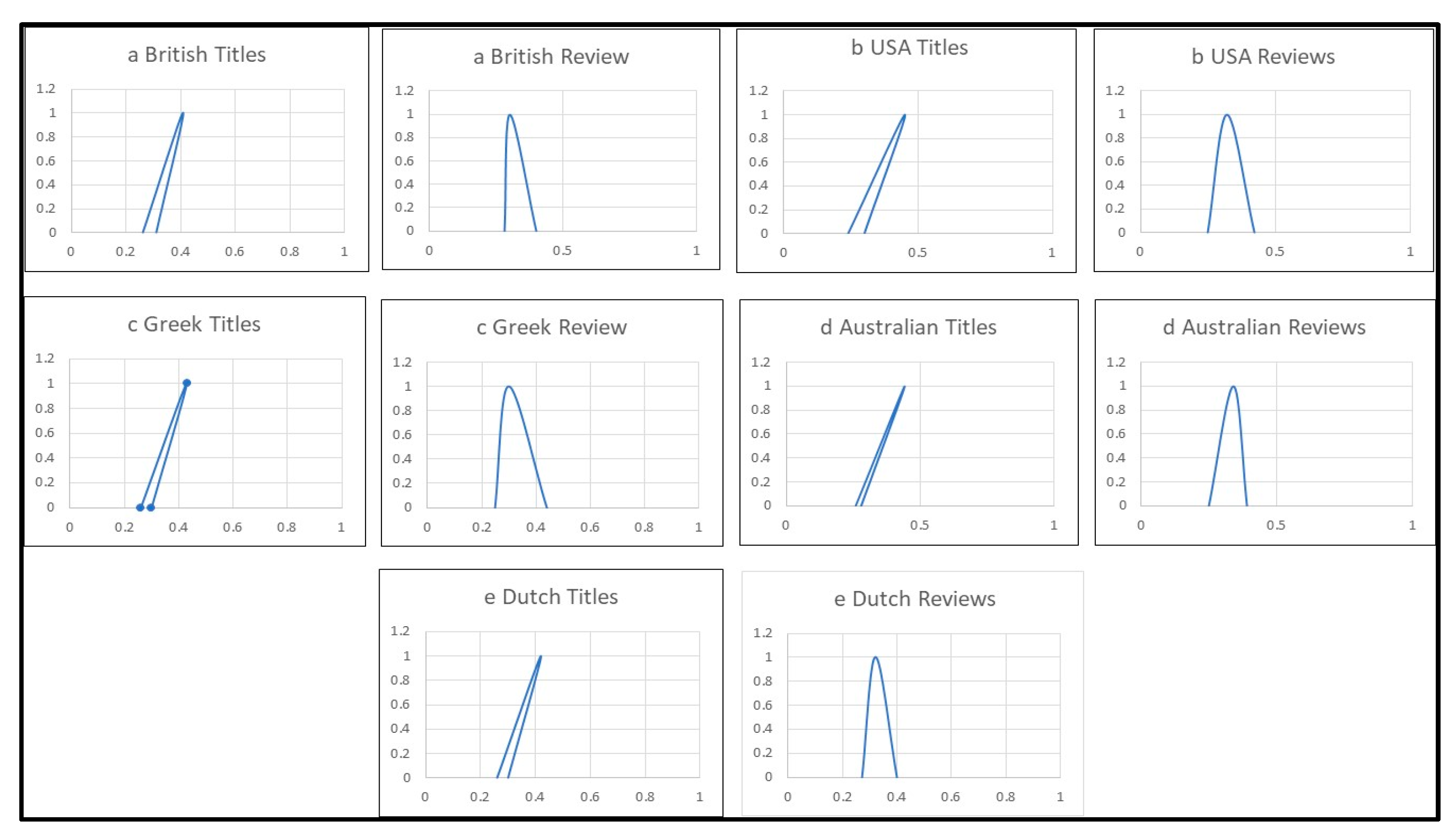

Next, the fuzzification of titles and reviews word numbers is performed by using equation (1), and the TFN membership functions shown in

Table 4.

Following the fuzzification, the articulacy for both titles and reviews is characterised in terms of the fuzzy sets {Low, Medium, High}, similarly as the sentiment is calculated as {Negative, Neutral, Positive}. The membership functions of articulacy are calculated according to [

64,

66,

67], in the same way this study calculates as sentiment membership functions. Of the total 42.678 British reviews in the sample, 31% of the titles were characterized as of low, 41% as of medium and 26% as of high longevity, respectively. Thus, for the British title articulacy the membership function is:

The rating given to each assessment grade (i.e. Negative=1, Neutral=2, Positive=3), is adopted by [

63,

64,

66,

67]. The resulting membership functions for title and reviews’ articulacy for each nationality are shown in

Table 5.

The articulacy fuzzy sets provide an indication of how informative the reviewers from each nationality are.

Figure 3 shows diagrammatically the differences in review titles’ longevity between the British and the USA users.

Figure 3 diagrams show that the British are closer to the USA and the Dutch users in terms of the titles’ articulacy, while the Greeks are closer to the Australians. With respect to the reviews the Greeks and the USA exhibit similar behaviour, while the British are more similar to the Dutch and the Australians. An analysis of similarities and differences among nationalities that would include other indicators such as gender, age, preferences, may be used in order to develop a more comprehensive users’ profile.

5.3. Assessing Usefulness of Reviews by incroporating users biases

Drawing on the membership functions shown in

Table 2 and

Table 5, by using equation (4) the membership function matrix

for the British users, is formed as follows:

Similarly, membership function matrices are calculated for all nationalities in the sample.

The importance matrix and the weights for each indicator are calculated using equations (6) and (7):

Thus,

Finally, the weights for the British users are:

Similarly, the weights for each nationality are:

The results indicate the differences as well as the similarities among the nationalities, which have been diagrammatically depicted in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Larger are the differences found in titles and reviews sentiments as compared to the differences in articulacy.

In order to calculate usefulness of reviews, assume Review-1 as an alternative in the FSE model. Review-1 can be a certain review or a collection of reviews over a period of time, e.g. 5 years. The aggregation of reviews over a period of time is suggested as especially useful [

38]. By using MS Azure sentiment analysis, Review-1, sentiment polarity is quantified with a positive, neutral, or negative value. The numerical values of Review-1 articulacy for both title and review are then fuzzified using equation (1) and the TFN membership functions shown in

Table 4.

Then the performance membership function matrix for Review-1, using equation (10) follows:

The aggregated performance evaluation, regarding the usefulness of alternative”

” is calculated using the fuzzy composition in equation (11):

Similarly, for the rest of the nationalities in the sample:

Finally, by using equations (12) and (13), the “Usefulness Score” =12,80. This score indicate how useful is for the British users to read the. Similarly, the usefulness score is calculated for each nationality as follows:

“Usefulness Score (British)” =12,80,

“Usefulness Score (USA)” =12,89,

“Usefulness Score (Greek)” =14,65,

“Usefulness Score (Australian)” =13,44,

“Usefulness Score (Dutch)” =14,73.

The “Usefulness Score” shows that

, is not equally useful for all nationalities. It is more useful for the Greeks, the Australians, and the Dutch to read, but not so, for the British and the USA users. The difference in usefulness lies in the fact that not all users exhibit the same behaviour when expressing themselves. Some may express themselves by using more words in their reviews or others may be more lenient than others or exhibit a behavior in between. As already discussed in the relevant literature [

35,

37,

55]not necessarily all nationalities will select the same set of reviews. The “Usefulness Score” can be used to rank reviews or a collection of reviews and assist users to focus on the most useful rev

6. Discussion

Behavioural differences exist among different nationalities in the way they express their sentiments. Some nationalities express their sentiments in the titles while others become more precise in their full reviews. Therefore, titles do not always convey in full what users’ sentiments imply that they may create a false perception of other reviewers’ experiences. An explanation may be that reviewers find more space in reviews’ documents to express their sentiments in more details. In particular, the British, followed by the Greeks exhibit a more consistent behaviour in expressing themselves. Users of both nationalities express themselves concisely in their reviews’ titles. By reading just the titles of reviews written by a British or a Greek reviewer, one can understand the reviewer’s negative feelings rather clearly. With respect to neutral sentiments the Greeks exhibit quite a varying behaviour, as opposed to the rest nationalities. Thus, neutral judgments are not so informative when they are expressed by Greek users. Regarding positive sentiments, reviews tend to be more lenient in their titles and more critical in their full documents. With the exception of the British rather balanced evaluations, positive scores are more frequent in titles than in reviews full documents for all other nationalities in the sample. Therefore, when positive sentiments are expressed, it is suggested that one should read the whole review document to have a more detailed understanding of the users’ experiences. By just reading the review title will not suffice to comprehend the thoughts of the user. The results of this research are in line with other studies [

35,

36,

55], and suggests that nationality may imply differences in the way users write review and express their sentiments.

This study indicates that there are differences among nationalities in the sample with respect to the number of words in the title, and the reviews documents. Although differences may not be as profound as in sentiments, results show that the British, the USA, the Greeks and the Australian reviewers exhibit similar behaviour regarding their reviews length. However, the Dutch reviewers are more frugal in their full reviews, since their average number of words is approximately half the average number of the rest of the nationalities.

This study suggests that fuzzy logic can be used to not only represent the differences in behaviour among nationalities as fuzzy sets but also to calculate the “usefulness” of a review by utilising the FSE. Fuzzy sets provide the means for quantifying the differences among users that imply the biases of different nationalities. The FSE of reviews’ usefulness can be used to suggest users to read the most suitable reviews for them through fuzzy relations composition. The most useful reviews are those which reflect their behaviour better. Therefore, the proposed approach can be used within the context of a voting system or online review platform [

38] that aims to assist users identify useful reviews that reflect their personalised preferences, behaviour, and perception. The current work, considers usefulness as the only criterion. The FSE and the fuzzy relations’ compositions can be used to combine several other characteristics of the reviews, e.g., publication date, features mentioned in reviews, etc.

7. Limitations of the study and Future Research

With respect to the limitations of this study, this research uses only one sentiment analysis method and focuses only on reviews’ sentiment polarity, strength and articulacy for certain nationalities. The plethora of data that can be collected from platforms such as Tripadvisor, Booking, etc., and the subsequent analysis of features such as gender, date of visit, date of review publication, etc., would result in more detailed insights of users’ ways of expressing their feelings, thus providing a more comprehensive view of biases. Furthermore, testing the efficiency of the proposed approach to accurately assess users’ sentiment when combined with sentiment analysis algorithms, would probably lead to developing domain specific sentiment analysis methods.

Future research may also focus on extending the modelling approach to include a broader perspective of users’ behaviour. Research efforts may focus on developing models that capture the different ways that users express themselves. Users do not all give the same sentiment strength even if they use the same or similar words in their reviews. Thus, the expressions “good service”, or “enjoyable experience” may not convey exactly the same meaning for all users. Since fuzzy logic allows for dealing with subjectivity, future research efforts may attempt to define different fuzzy sets for same concepts in order to reflect how different users perceive the same or similar expressions.

8. Conclusions

This study suggests that since bias affects users’ perception of reviews sentiment and length, fuzzy logic provides the necessary theoretical and methodological foundation to measure reviews’ usefulness. User reviews’ sentiment is subjective. Bias attributed to gender, nationality, etc., inherited in sentiment analysis has been examined in many studies. Fuzzy logic provides the means to deal with impartial information which is often found in reviews and represent the subjectivity that is embedded in how people with different cultural backgrounds, from different age groups, with varying preferences express their experiences. This study analysed users' reviews and calculated the membership functions of fuzzy sets that exhibit the bias as well as the similarities inherited among nationalities and expressed by the way they communicate their sentiments and write their reviews. Results identify aspects, such as the bias attributed to different nationalities as expressed in terms of sentiment expressed in titles or the reviews as well as titles and reviews articulacy. Such aspects, if not overrepresented or underrated, may increase the accuracy of sentiment analysis techniques thus improving reviews readability and usefulness when judging a service or a product.

Author Contributions

For Conceptualization, D.K.K., C.T., S.B., P.T., and K.A.; methodology, D.K.K., C.T., S.B., P.T., and K.A.; validation, D.K.K., C.T., S.B., P.T., and K.A.; formal analysis, D.K.K., C.T., S.B., P.T., and K.A.; investigation, D.K.K., C.T., S.B., P.T., and K.A.; resources, D.K.K., C.T., S.B., P.T., and K.A.; data curation, D.K.K., C.T., S.B., P.T., and K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.K., C.T., S.B., P.T., and K.A.; writing—review and editing, D.K.K., C.T., S.B., P.T., and K.A.; supervision, D.K.K., C.T., S.B., P.T., and K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- B. Liu, Sentiment Analysis Essentials Sentiment Analysis: Mining Opinions, Sentiments, and Emotions. Cambridge, 2015.

- L. Yu, L. Wang, D. Liu, and Y. Liu, ‘Research on Intelligence Computing Models of Fine-Grained Opinion Mining in Online Reviews’, IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 116900–116910, 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Oktaviani, B. Warsito, H. Yasin, R. Santoso, and Suparti, ‘Sentiment Analysis of e-Commerce Application in Traveloka Data Review on Google Play Site Using Naïve Bayes Classifier and Association Method’, in Journal of Physics: Conference Series, IOP Publishing Ltd, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Wang, X. Zhu, and L. Yan, ‘Sentiment Analysis for E-Commerce Reviews Based on Deep Learning Hybrid Model’, in 5th International Conference on Signal Processing and Machine Learning (SPML), Association for Computing Machinery, Aug. 2022, pp. 38–46. [CrossRef]

- P. Savci and B. Das, ‘Prediction of the Customers’ Interests Using Sentiment Analysis in e-Commerce Data for Comparison of Arabic, English, and Turkish Languages’, Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 227–237, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Hossain, D. Das Joy, S. Das, and R. Mustafa, ‘Sentiment Analysis on Reviews of e-commerce Sites Using Machine Learning Algorithms’, in International Conference on Innovations in Science, Engineering and Technology (ICISET) 2022, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022, pp. 522–527. [CrossRef]

- P. Rajesh and G. Suseendran, ‘Prediction of N-Gram Language Models Using Sentiment Analysis on E-Learning Reviews ’, International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM), pp. 510–514, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. A. dos Santos Alencar, J. F. de Magalhães Netto, and F. de Morais, ‘A Sentiment Analysis Framework for Virtual Learning Environment’, Applied Artificial Intelligence, vol. 35, no. 7, pp. 520–536, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Yan, F. Jian, and B. Sun, ‘SAKG-BERT: Enabling Language Representation with Knowledge Graphs for Chinese Sentiment Analysis’, IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 101695–101701, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. F. Sayeedunnisa and M. Hijab, ‘Impact of e-Learning in Education Sector: A Sentiment Analysis View’, in IEEE Conference on Interdisciplinary Approaches in Technology and Management for Social Innovation (IATMSI), Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- L. K. Singh and R. Renuga Devi, ‘Analysis of Student Sentiment Level Using Perceptual Neural Boltzmann Machine Learning Approach for E-learning Applications’, in 5th International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies, ICICT 2022 - Proceedings, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022, pp. 1270–1276. [CrossRef]

- Z. Khanam, ‘Sentiment Analysis of User Reviews in an Online Learning Environment: Analyzing the Methods and Future Prospects’, European Journal of Education and Pedagogy, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 209–217, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Krouska, Troussas, and Virvou, ‘Deep Learning for Twitter Sentiment Analysis: The Effect of Pre-Trained Word Embeddingd’, in Machine Learning Paradigms. Learning and Analytics in Intelligent Systems, Springer Cham., vol. 18, Tsihrintzis G and Jain L, Eds., 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, Y. Wu, Y. Zhang, and T. Zhao, ‘Time+User Dual Attention Based Sentiment Prediction for Multiple Social Network Texts with Time Series’, IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 17644–17653, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Wang, K. Lu, K. P. Chow, and Q. Zhu, ‘COVID-19 Sensing: Negative Sentiment Analysis on Social Media in China via BERT Model’, in IEEE Access, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2020, pp. 138162–138169. [CrossRef]

- F. Alattar and K. Shaalan, ‘Using Artificial Intelligence to Understand What Causes Sentiment Changes on Social Media’, IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 61756–61767, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Silva, E. Andrade, D. Araújo, and Dantas J., ‘Sentiment Analysis of Tweets Related to SUS Before and During COVID-19 Pandemic’, Proceedings of the IEEE Latin America Transactions, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 6–13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Rodríguez-Ibánez, A. Casánez-Ventura, F. Castejón-Mateos, and P. M. Cuenca-Jiménez, ‘A review on Sentiment Analysis from Social Media Platforms’, Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 223. Elsevier Ltd, Aug. 01, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Krouska, C. Troussas, and M. Virvou, ‘Comparative Evaluation of Algorithms for Sentiment Analysis over Social Networking Services’, Journal of Universal Computer Science (JUCS), vol. 23, no. 8, pp. 755–768, 2017, [Online]. Available: http://www.internetlivestats.com/.

- J. Usher, L. Morales, and P. Dondio, ‘BREXIT: A Granger Causality of Twitter Political Polarisation on the FTSE 100 Index and the Pound’, in Proceedings - IEEE 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Knowledge Engineering, AIKE 2019, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Jun. 2019, pp. 51–54. [CrossRef]

- N. Shaghaghi, A. M. Calle, J. Manuel Zuluaga Fernandez, M. Hussain, Y. Kamdar, and S. Ghosh, ‘Twitter Sentiment Analysis and Political Approval Ratings for Situational Awareness’, Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Cognitive and Computational Aspects of Situation Management (CogSIMA), pp. 59–65, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Schmale and V. Mittendorf, ‘Detecting Negative Campaigning on Twitter Against The Greens’, Proceedings of the IEEE Ninth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS), pp. 1–8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Orellana and H. Bisgin, ‘Using Natural Language Processing to Analyze Political Party Manifestos from New Zealand †’, Information (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 3, p. 152, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Ligthart, C. Catal, and B. Tekinerdogan, ‘Systematic Reviews in Sentiment Analysis: a Tertiary Study’, Artif Intell Rev, vol. 54, no. 7, pp. 4997–5053, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Thelwall, D. Wilkinson, and S. Uppal, ‘Data Mining Emotion in Social Network Communication: Gender Differences in MySpace’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 190–199, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Volkova and B. Yoram, ‘On Predicting Sociodemographic Traits and Emotions from Communications in Social Networks and their Implications to Online Self-Disclosure’, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2015, 18, 726–736. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Babac and V. Podobnik, ‘A Sentiment Analysis of Who Participates, How and Why, at Social Media Sport Websites: How Differently Men and Women Write About Football’, Online Information Review, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 814–833, 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Rangel and P. Rosso, ‘On the Impact of Emotions on Author Profiling’, Inf Process Manag, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 73–92, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Thelwall, ‘Gender Bias in Sentiment Analysis’, Online Information Review, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 45–57, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Rajshakhar, A. Bosu, and S. Z. Kazi, ‘Expressions of Sentiments During Code Reviews: Male vs. Female’, IEEE 26th international conference on software analysis, evolution and reengineering (SANER), pp. 26–37, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Sun et al., ‘Mitigating Gender Bias in Natural Language Processing: Literature Review’, in 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 1630–1640. Accessed: Feb. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available:. [CrossRef]

- F. Villarroel Ordenes and R. Silipo, ‘Machine Learning for Marketing on the KNIME Hub: The Development of a Live Repository for Marketing Applications’, J Bus Res, vol. 137, pp. 393–410, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. López, A. Valdivia, E. Martínez-Cámara, M. V. Luzón, and F. Herrera, ‘E2SAM: Evolutionary Ensemble of Sentiment Analysis Methods for Domain Adaptation’, Inf Sci (N Y), vol. 480, pp. 273–286, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Davis, C. J. Worsnop, and E. M. Hand, ‘Gender Bias Recognition in Political News Articles’, Machine Learning with Applications, vol. 8, no. 100304, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Kim, M. Jun, and C. K. Kim, ‘The Effects of Culture on Consumers’ Consumption and Generation of Online Reviews’, Journal of Interactive Marketing, vol. 43, pp. 134–150, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Litvin, ‘Hofstede, Cultural Differences, and TripAdvisor hotel Reviews’, International Journal of Tourism Research, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 712–717, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. W. T. Ngai, V. C. S. Heung, Y. H. Wong, and F. K. Y. Chan, ‘Consumer Complaint Behaviour of Asians and non-Asians About Hotel Services: An Empirical Analysis’, Eur J Mark, vol. 41, no. 11–12, pp. 1375–1391, 2007. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Choi and S. Leon, ‘An Empirical Investigation of Online Review Helpfulness: A Big Data Perspective’, Decis Support Syst, vol. 139, no. 113403, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, X. Zhang, S. Liang, Y. Yang, and R. Law, ‘Infusing New Insights: How Do Review Novelty and Inconsistency Shape the Usefulness of Online Travel Reviews?’, Tour Manag, vol. 96, no. 104703, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. H. Park and J. Lee, ‘eWOM Overload and its Effect on Consumer Behavioral Intention Depending on Consumer Involvement’, Electron Commer Res Appl, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 386–398, Dec. 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. Siering, J. Muntermann, and B. Rajagopalan, ‘Explaining and Predicting Online Review Helpfulness: The Role of Content and Reviewer-Related signals’, Decis Support Syst, vol. 108, pp. 1–12, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Hong, D. Xu, G. A. Wang, and W. Fan, ‘Understanding the Determinants of Online Review Helpfulness: A Meta-Analytic Investigation’, Decis Support Syst, vol. 102, pp. 1–11, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Lee and J. Y. Choeh, ‘The Interactive Impact of Online Word-Of-Mouth and Review Helpfulness on Box Office Revenue’, Management Decision, vol. 56, no. 4, pp. 849–866, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Q. Cao, W. Duan, and Q. Gan, ‘Exploring Determinants of Voting for the “Helpfulness” of Online User Reviews: A Text Mining Approach’, Decis Support Syst, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 511–521, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- H. Baek, J. Ahn, and Y. Choi, ‘Helpfulness of Online Consumer Reviews: Readers’ Objectives and Review Cues’, International Journal of Electronic Commerce, vol. 17, no. 2. pp. 99–126, Jan. 01, 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. Racherla and W. Friske, ‘Perceived “Usefulness” of Online Consumer Reviews: An Exploratory Investigation Across Three Services Categories’, Electron Commer Res Appl, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 548–559, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu and S. Park, ‘What Makes a Useful Online Review? Implication for Travel Product Websites’, Tour Manag, vol. 47, pp. 140–151, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang and Z. Lin, ‘Predicting the Helpfulness of Online Product Reviews: A Multilingual Approach’, Electron Commer Res Appl, vol. 27, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Chatterjee, ‘Drivers of Helpfulness of Online Hotel Reviews: A Sentiment and Emotion Mining Approach’, Int J Hosp Manag, vol. 85, no. 102356, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Bigne, C. Ruiz, A. Cuenca, C. Perez, and A. Garcia, ‘What Drives the Helpfulness of Online Reviews? A Deep Learning Study of Sentiment Analysis, Pictorial Content and Reviewer Expertise for Mature Destinations’, Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, vol. 20, p. 100570, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhu, G. Yin, and W. He, ‘Is this Opinion Leader’s Review Useful? Peripheral Cues for Online Review Helpfulness’, Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 267, 2014.

- S. M. Mudambi and D. Schuff, ‘What Makes a Helpful Online Review? A Study of Customer Reviews on Amazon.com’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 185–200, 2010, [Online]. Available: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2175066.

- A. Y. K. Chua and S. Banerjee, ‘Understanding Review Helpfulness as a Function of Reviewer Reputation, Review Rating, and Review Depth’, Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, vol. 66, no. 2. John Wiley and Sons Inc., pp. 354–362, Feb. 01, 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Onikoyi, N. Nnamoko, and I. Korkontzelos, ‘Gender Prediction with descriptive Textual Data Using a Machine Learning Approach’, Natural Language Processing Journal, vol. 4, no. 100018, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Rita, R. Ramos, M. T. Borges-Tiago, and D. Rodrigues, ‘Impact of the Rating System on Sentiment and Tone of Voice: A Booking.com and TripAdvisor Comparison Study’, Int J Hosp Manag, vol. 104, no. 103245, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Gitto and P. Mancuso, ‘Improving Airport Services Using Sentiment Analysis of the Websites’, Tour Manag Perspect, vol. 22, pp. 132–136, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Wojarnik, ‘Sentiment Analysis as a Factor Included in the Forecasts of Price Changes in the Stock Exchange’, in Procedia Computer Science, Elsevier B.V., 2021, pp. 3176–3183. [CrossRef]

- M. Jiang, T. Y. Chen, and S. Wang, ‘On the Effectiveness of Testing Sentiment Analysis Systems with Metamorphic Testing’, Inf Softw Technol, vol. 150, no. 106966, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Dhakate and R. Joshi, ‘Classification of Reviews of e-healthcare Services to Improve Patient Satisfaction: Insights from an Emerging Economy’, J Bus Res, vol. 164, pp. 114–115, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Y. Lin, P. Y. Hsu, and G. J. Sheen, ‘A Fuzzy-Based Decision-Making Procedure for Data Warehouse System Selection’, Expert Syst Appl, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 939–953, Apr. 2007. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Ross, Fuzzy Logic with Engineering Applications, 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- P. Luukka, ‘Similarity Classifier Using Similarities Based on Modified Probabilistic Equivalence Relations’, Knowl Based Syst, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 57–62, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- G. Hu, H. Liu, C. Chen, P. He, J. Li, and H. Hou, ‘Selection of Green Remediation Alternatives for Chemical Industrial Sites: An Integrated Life Cycle Assessment and Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation Approach’, Science of the Total Environment, vol. 845, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, J. F. Y. Yeung, A. P. C. Chan, D. W. M. Chan, S. Q. Wang, and Y. Ke, ‘Developing a Risk Assessment Model for PPP projects in China-A Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation Approach’, Autom Constr, vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 929–943, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Akter et al., ‘Risk Assessment Based on Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation Method’, Science of the Total Environment, vol. 658, pp. 818–829, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhao, B. G. Hwang, and Y. Gao, ‘A Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation Approach for Risk Assessment: A Case of Singapore’s Green Projects’, J Clean Prod, vol. 115, pp. 203–213, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Yager R.R., ‘On Ordered Weighted Averaging Aggregation Operators in Multicriteria Decision Making’, IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 183–190, 1988. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).