1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are the two main forms of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD)s. CD can affect any part of the gastrointestinal system, and patients can present with multiple symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, cramping and blood in the stools [

1,

2].

CD is a chronic disease that cannot be fully cured, the main clinical therapies are focused on slowing down CD progression using anti-inflammatory approaches such as biological therapies and steroids [

3,

4].

Multiple factors contribute to the pathophysiology of IBD and the consequent manifestation of a wide range and severity of symptoms, including the intestinal microbial communities (microbiome), immune responses, psychological stress, and patient’s genetic susceptibility to the disease [

5,

6,

7]. Specifically, genetically predisposed subjects can commonly experience an inappropriate immune response to intestinal commensal microbes [

8].

Recently, several studies showed that the fungal community (mycobiome), an essential and integral component of the intestinal microbial population, can affect the pathogenesis of CD [

9]. The mycobiome resides in any part of the digestive tract and mostly consists of commensal fungi. However, in some instances, intestinal fungal commensals can overgrow and become opportunistic pathogens, therefore contributing to the etiology of IBD, particularly in more susceptible individuals such as immunocompromised patients [

10].

Clinical studies on immunocompromised individuals show that most fungal infections in CD patients are caused by

Candida (C.) albicans and

C. tropicalis, identifying these fungi as the most common pathogenic yeasts worldwide [

11,

12].

C. albicans and

C. tropicalis are normal components of human microbiota commonly present in the gastrointestinal system, epidermis and genital tract [

13].

C. tropicalis is characterized by high resistance to antifungal treatments, such as amphotericin B and azoles derivatives [

14], and has been identified as the second most common pathogenic yeast in IBD patients, after

C. albicans. It is significantly more abundant in CD patients compared to their non-CD relatives [

15].

Candida species exist in both yeast and hyphal forms based on the surrounding environment, and have been the most commonly reported fungal species causing infections in IBD patients

, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract [

16]

. One of the most important C. albicans virulence factors is its capacity to form polymicrobial biofilms (PMB)s

on the colonized surface of the host, thereby promoting associations with several types of bacteria [

17]

. The ability of C. albicans to form polymicrobial associations indicates that crosstalk between the mycobiome and microbiome may negatively affect the host. The underlying mechanism/s for this detrimental effect is attributed to yeasts ability to form filaments and secrete extracellular enzymes (aspartic proteinase and phospholipases) [

18,

19]

leading to apoptosis, oxidative damage, and significantly increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, eventually inducing an abnormal host inflammatory response [

20]

, resulting in the breakdown of the epithelial cell lining and leaky gut.

Within PMBs, associations between fungi and bacteria, bacteria and bacteria, and fungi and fungi may be either commensal, mutualistic or antagonistic [

21]

. Numerous microbes have evolved to exhibit specific attraction to neighboring species in order to survive environmental challenges [

22]

, leading to immune system evasion, metabolic cooperation and more efficient host colonization [

23,

24].

Since

Candida-induced dysbiosis has been shown to be detrimental in both CD patients and CD-mouse models [

25], understanding the molecular mechanisms by which fungi interact with the other gut-residing microorganisms may enlighten approaches to rebalance and maintain the microbiome and consequently help patients to prevent flare ups of symptoms. In this context, to gain insight into the mechanism/s underlying the interactions between the two pathogenic

Candida species when present in the same environment, we evaluated the influence of

C. tropicalis on the pathogenicity of

C. albicans. Employing a dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)- induced colitis model in C57BL/6 (B6) mice, we assessed the susceptibility and pathogenicity in mice inoculated with only

C. albicans, only

C. tropicalis or a combination of both

Candida species.

We report herein that C. tropicalis established antagonistic interactions with C. albicans affecting its virulence profile, as the mice co-colonized with both Candida species were less susceptible to DSS-induced colitis compared to mice inoculated with C. albicans only. Mechanistically, we showed that C. tropicalis competes with C. albicans for the growth in the gut, decreasing the capacity of C. albicans to produce biofilm and consequently adhere to the host.

Finally, we demonstrated that the production of multiple short-chain fatty acids (SCFA)s and the expression of genes involved in immune response were altered when the combined Candida species interacted in the co-colonized mice compared to mice inoculated with only single Candida species.

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

B6 mouse colony was bred at Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, OH). The age of the mice used in the experiments was between 15 and 17 weeks. An equal number of males and females was used for the experiments. Micro-isolator cages (Allentown Inc, Allentown, NJ) with 1/8-inch corn bedding were used to house the mice. Mice consumed laboratory rodent diet P3000 (Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN) during the experiments. Mice were randomized using a numerical code, so the experiments could be performed in a blinded manner. The numerical code was only revealed at the end of the experiment.

Fecal pellets homogenization

50 grams of corn bedding (including fecal pellets) were collected from each experimental cage a week before Candida inoculation and blended together. The total collected pellet was then homogenized for 2 minutes. Then, 50 grams of the homogenized pellet was redistributed to the experimental cages. This method was adopted to limit the variability between cages caused by bacterial changes.

Colitis induction

Mice were exposed to 3% DSS (TdB Labs AB, Uppsala, Sweden) for 7 days in drinking water to induce acute colitis. The DSS solution in drinking water was renewed every 4 days. Mice were monitored daily to assess body weight and intestinal bleeding

Yeast Strains and Growth Conditions

The C. albicans strain SC5314 and the C. tropicalis strain MRL32707 were the infecting fungi. Cells were propagated for 24 hrs at 37°C in Sabouraud Dextrose Broth containing 50 mM glucose. Cells were centrifuged, and the supernatant was decanted and filter sterilized to be used for biofilm experiments. Cell pellets were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2), and standardized to 1 x 107 cells/mL.

Biofilm Formation

12 mm silicone elastomer discs were cut from a sheet of silicone sheeting (Invotec International, Jacksonville, FL) and used as scaffold for handling biofilms. 4 mL of inoculum of either C. tropicalis or C. albicans standardized to 1 x 107 cells/mL was applied to each disc and left to incubate for 90 min at 37°C (adhesion phase). Discs were then placed into new wells containing 4 mL of either 100% Sabouraud Dextrose Broth or 50% (v/v) Sabouraud Dextrose Broth/cell-free supernatant of the other organism. Discs were incubated for 24 hrs at 37°C (biofilm growth phase).

Quantitative Measurement of Biofilms

Quantification of

yeast biofilms was performed as described previously [

26]. Briefly, dry-weight analysis determined the total biofilm mass (comprising extracellular matrix and fungal cells). Mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity was utilized as an indicator of the metabolic state of the

Candida cells and quantified using a colorimetric method which involves the reduction of 2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl] 2H-tetrazoliumhydroxide (XTT) to a formazan compound whose absorbance is subsequently read utilizing a spectrophotometer. In order to determine the dry-weight, the biofilms were incubated into new wells containing 4 mL of PBS with 1 mM menadione and 1 mg/mL of XTT at 37°C for 16 hours. Next, the biofilms were scrapped from the discs and placed into a conical tube, centrifuged for 7 minutes at 3500 x g. Then, 1 mL of the supernatant from each conical tube was loaded into a cuvette and a spectrophotometer was utilized to record the absorbance at 520 nm. The remaining fungal pellets were filtered using a previously weighted strainer (0.45 µm pore size), dried up for 24 hrs at 35°C, and then weighed.

Yeasts challenge and determination of CFUs

Candida strains were first plated on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) and incubated at 37° C for 2 days and then harvested through centrifugation. Then, a hemocytometer was used to prepare a challenge inoculum of 1×109/ml for each strain. All experimental mice were then inoculated with 1×108 Candida cells in 100 μL of normal saline through gavage technique for three consecutive days. This process was performed four days before the 3% DSS administration in drinking water.

Quantification of colony-forming units (CFUs/ml) was determined by plating on SDA. CFUs were calculated as log CFUs per g of stools. As control, an additional cohort of mice was challenged with nonpathogenic yeast Saccharomycopsis (S.) fibuligera.

Histology

Colons from yeast-challenged mice were removed and fixed in Bouin’s solution for 24 hours. Then, tissues were embedded in paraffin and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining. Inflammation was assessed by a pathologist using a scoring system previously described [

27]. Scores varying from 0 (normal) to 3 (maximum severity) were utilized to assess four individual histologic parameters: (1) percent ulceration, (2) chronic inflammation (macrophages and lymphocytes in the mucosal and submucosal layers), (3) percent ulceration and (4) acute inflammation (neutrophils).

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy was conducted using a flexible ureteroscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA). Colonoscopy images were acquired on an Olympus BX41 microscope. Mice were subjected to colonoscopy the day after the end of DSS administration. Colonic inflammation was assessed using a scoring system previously described [

28]. Scores varying from 0 (normal) to 3 (maximum severity) were utilized to evaluate four individual colonoscopic parameters: (1) intestinal bleeding, (2) wall transparency, (3) perianal findings (including rectal prolapse and diarrhea ) and (4) focal lesions (including ulcers and polyps). Isoflurane (Butler Schein Animal Health, Dublin, OH) was utilized to anesthetize the mice prior to colonoscopy procedure.

Flow Cytometry

Mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN)s were crushed using a 40-μm nylon mesh. In order to determine cell viability, cell suspensions of MLNs were incubated with live/dead Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit and live/dead Fixable Violet (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, WA). FACS buffer was then used to wash the cells. Next, cells were first incubated with fluorescently conjugated antibodies at 4 °C for 20 mins and then fixed in the dark with fixation/permeabilization buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) at 4°C for 30 min. In order to detect intracellular proteins, cells were then stained with a mix of fluorescently conjugated antibodies at RT for 30 min. The detection of lymphocytes expressing cytokines was then performed by using the following antibodies: IL-17A (TC11-18H10.1, Sony, Bothell, WA), IFNγ (XMG1.2, Biolegend, San Diego, CA), antibody mix containing antibodies raised against CD3 (145-2C11, BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Canada), IL-4 (11B11, Sony, Bothell, WA) and TNF (MP6-XT22, Biolegend, San Diego, CA). FACSAria sorter was used to perform flow-cytometric acquisition. Data were then analyzed with FlowJo_V10 software (Tree Star, Inc.). Gating strategy for lymphocytes: T lymphocytes were determined by gating on CD3+ live cells, followed by gating on singlets utilizing height vs. forward scatter area and dead-cell exclusion. Finally, specific gating was performed for subsets positive for IFN, IL-4, TNF and IL-17.

Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) technique was performed to evaluate SCFAs extracted from mouse stools through a previously described method [

29]. In brief, 50 mg of stools were collected from each mouse and placed into a 1.5 mL tube containing 3.2 mm beads and 300 μL of water. Stools were then homogenized with a homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH).

After centrifugation for 10 min at 14,000 x g, the supernatant was placed into a new 1.5 mL tube.

100 μL of 172mM Pentafluorobenzyl Bromide in acetone was then added to each tube. After incubation at 60°C for 30 min, 250 μL of water and 500 μL of n-hexane were added to each tube. Next, 1 μL of each sample was inserted in the GC/MS instrument (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Methane was utilized as ionization gas. Ions acquired were detected in the negative mode utilizing selected ion monitoring. Linear regression was then performed to determine the slope for each SCFA. Finally, the concentration of each SCFA was determined by using the area ratios acquired from each stool sample and the slopes previously obtained.

Immunohistochemistry

In order to perform the immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, tissue samples were embedded in paraffin and then sectioned (thickness: 3-4 μm). Next, sections were placed on Plus slides (Thermo Scientific, Logan, UT) and then deparaffinized. Then, sections were incubated in normal serum for blocking non-specific binding. 1.75% H2O2 was utilized to block samples for endogenous peroxidase activity. Slides were then incubated first with polyclonal rabbit anti-C. albicans primary antibody at 1:100 (PA17206; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 4°C and then with an appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Newark, CA). Next, slides were assayed utilizing a Vectastain ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories), and immunoreactive cells were detected using a diaminobenzidine substrate (Vector Laboratories). Finally, slides were counterstained using hematoxylin and then were mounted utilizing an 80% glycerol mount. Negative controls were prepared following the same procedure in the absence of the anti-C. albicans primary antibody.

NanoString Gene Expression Analysis

Colon tissues were homogenized using 100 mg of 1.4-mm beads at 4,000 rpm. Next, total RNA was isolated with a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Gene expression was determined using a previously described protocol [

7]. Briefly, RNA was incubated with a panel presenting 785 bar-coded probes (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA) targeting specific genes associated with 50 cellular pathways involved in immune responses. Samples, hybridization solution and probes were subjected to hybridization for 24 hours at 65°C. Next, samples were processed in the NanoString Prep Station. The target/probe compounds were placed in a cartridge for data collection. Differential expression was determined using the following criteria:

P < 0.05 and fold change >1.25. Data analysis was obtained using the ROSALIND® online platform (

https://rosalind.onramp.bio). Heatmaps and volcano plots showing clustering of genes differently expressed between the experimental groups were obtained utilizing the “Partitioning Around Medoids” algorithm combined with the “Flexible Procedures for Clustering” R library and multiple database sources including WikiPathways [

30] and NCBI [

31]

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was conducted in duplicate. Collective data from replicated experiments were utilized to conduct multivariate and univariate analyses. Continuous data of the experimental groups were compared using the Student’s unpaired t test. Data were expressed as means ± SEM. An alpha level of 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA).

All authors had access to the study data and have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

4. Discussion

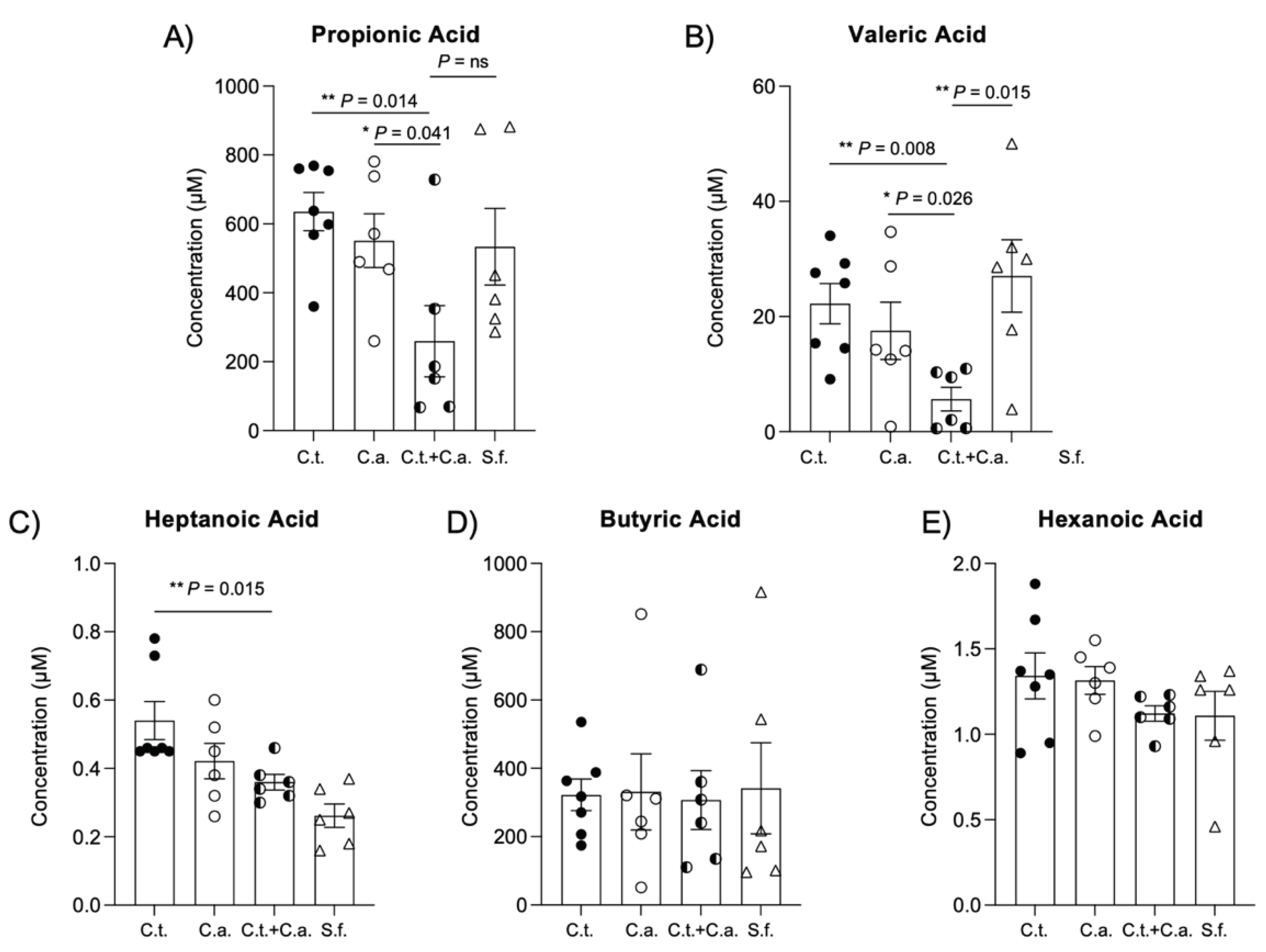

We report that inoculation with C. tropicalis is associated with decreased severity of DSS-induced colitis in B6 mice challenged with C. albicans. Decreased pathogenicity is indicated by decreased histological and colonoscopic scores, and result in a better physiological outcome. This result is likely to be mediated by close interactions between yeasts and beneficial bacteria which take place during chemically induced colitis, as indicated by changes in the production of certain bacterial SCFAs. These SCFAs, such as propionic and valeric acid, were found to be consistently decreased in stool samples of co-inoculated mice compared to Candida mono-inoculated mice.

Propionic acid is a metabolite produced by specific bacterial species, such as

Escherichia (E.) coli, following fermentation of dietary fibers. Previous

in vitro studies demonstrated a positive correlation between elevated levels of propionic acid and higher levels of virulence of

E. coli (specifically its ability to penetrate and colonize phagocytes) isolated from CD patients [

32]. In addition, the observed levels of valeric acid were significantly lower in the stools of co-inoculated mice compared to mice challenged with

C. albicans only, suggesting a correlation between the dysbiosis obtained with

C. albicans mono-inoculation and the growth of specific bacteria producing valeric acid. Valeric acid has previously been shown to increase the inflammatory response mediated by IL-17 signaling pathway in a recent study [

33].

In the present work, we also defined the immunological aspects of the decreased colitis that occurred in the experimental group inoculated with

C. albicans and

C. tropicalis combined. First, we detected upregulation of Th-2 immunity in co-inoculated mice with significantly increased IL-4 production compared to the mice challenged with

C. albicans alone. Our data agree with those of Mencacci

et al. [

34], who found that endogenous IL-4 is essential for stimulating CD4

+ defensive responses against

C. albicans through the activation of the adaptive and innate immune systems. Furthermore, levels of IL-4 measured in the co-inoculated group were similar to those of the control group. Interestingly, these data are consistent with our previous study [

35], showing significantly decreased

IL-4 expression in mice inoculated with a single

Candida species compared to the control group. Second, we also detected significant downregulation of Th-17 immunity in mice challenged with

C. albicans compared to the control group. These data are expected, given the well-known protective role of Th-17 cells in antifungal immune responses, where several genetic anomalies involving IL-17 signaling cascade have been proven to increase susceptibility to mucocutaneous candidiasis in multiple mouse models and human subjects [

36,

37]. Conversely, the level of IL-17 produced in the co-inoculated mice was significantly higher compared to mice inoculated with

C. albicans only. This can be explained by the interesting theory that

C. tropicalis and

C. albicans, rather than having a mutualistic interaction, compete for adherence and growth in the same host niche, affecting the microbiome and the immune response differently compared to when they are present as the sole fungal source. This theory is supported by the observation that several microorganisms present in the gut have different effects based on their interaction with other microbial species. For example, published data have shown that

C. albicans has a protective effect in DSS-treated germ-free mice, as well as antibiotic-treated specific-pathogen-free mice, two models used to study the effect of

Candida species in the context of a depleted/absent gut microbial community [

38]. By contrast, another study published by Jawhara

et al. [

39] has shown, in accordance with our results, that the decrease of

C. albicans caused by

Saccharomyces boulardii inoculation was positively correlated with decreased susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis. Our data indicate that the specific bacterial populations responsible for the increased susceptibility to chemically induced colitis are those microbes also affected by

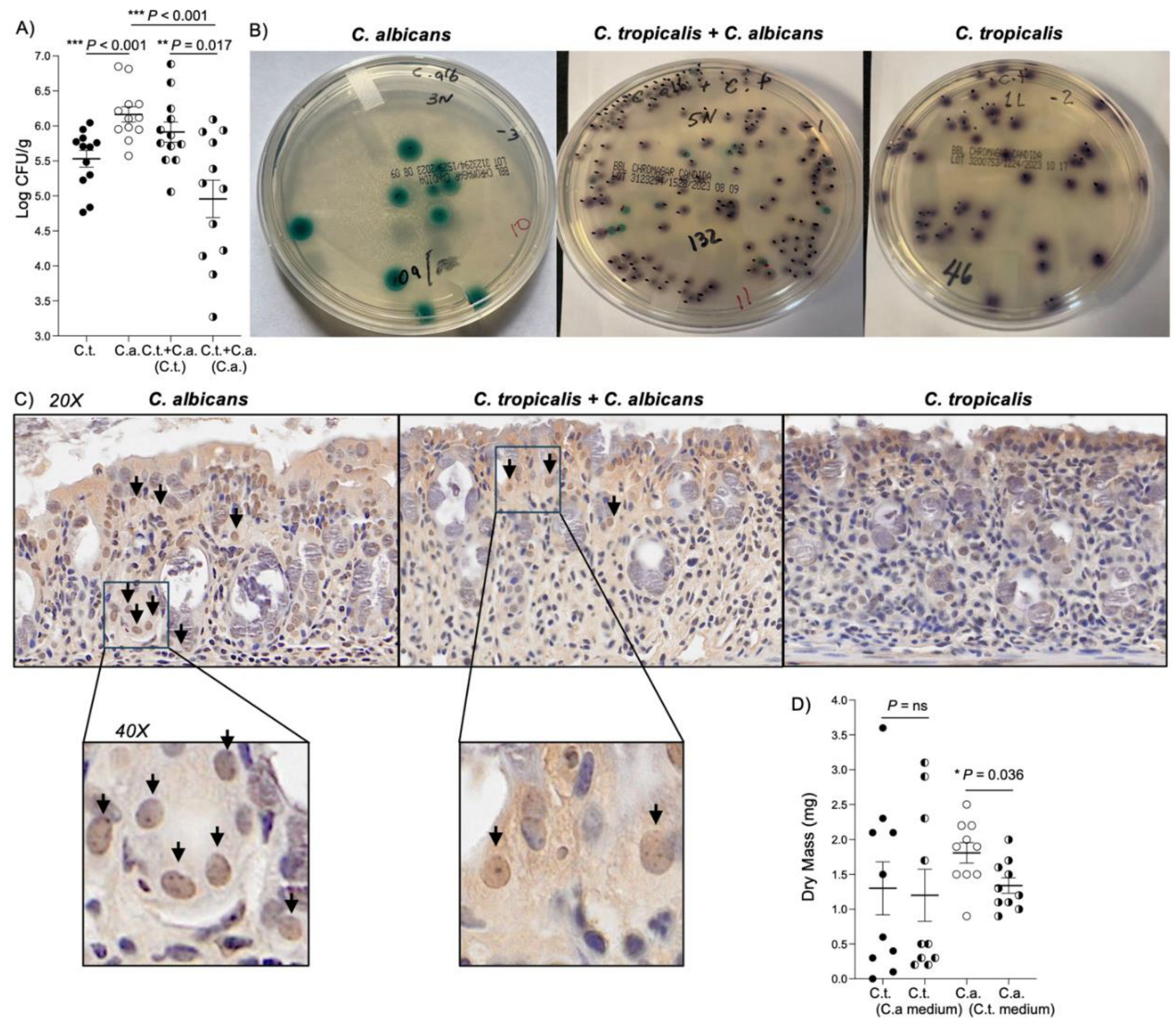

C. albicans inoculation, thus explaining the divergence in outcome between our own studies with those published previously. In support of our theory, CFU analyses show that the quantitative recovery of

C. albicans from the fecal samples of the experimental group inoculated with both yeasts was significantly inferior compared to the colonies obtained from fecal material of mice inoculated with

C. albicans alone. This observation strongly suggests that

C. tropicalis was able to reduce the growth and the adherence capacity of

C. albicans. To corroborate our hypothesis, the

in vitro XTT assay highlighted a marked decrease of

C. albicans biofilm production in

C. albicans cultured in the presence of

C. tropicalis supernatant, demonstrating that certain metabolites produced by

C. tropicalis impair the adherence ability of

C. albicans. Our data are in agreement with those of Santos

et al. [

40] who demonstrated that

C. tropicalis was capable of limiting

C. albicans metabolic activity and its capacity to form colonies in mixed biofilms. In contrast, quantification of

C. tropicalis CFUs in the co-inoculated mice was similar to the level of CFUs quantified in the group inoculated with

C. tropicalis alone, and in accordance with these data, the XTT assay showed that

C. tropicalis biofilm production was not altered in

C. tropicalis cultured with

C. albicans supernatant. Our hypothesis was further supported by IHC staining specific for

C. albicans, showing that this yeast was not only more abundant, but it was also able to penetrate deeper in the epithelium and into the lamina propria of mice mono-inoculated with

C. albicans compared to the co-inoculated group, where

C. albicans was mainly located on the epithelial surface.

Lastly, NanoString analysis showed that

C. tropicalis inoculation not only drastically limited the virulence and the growth of

C. albicans, but it also critically affected the expression of 7 genes implicated in interferon signaling, complement cascade and response to TGF- β family members in

C. albicans-challenged mice, via genes such as

Ccr9,

Nkg7,

Acsl1,

Ifngr1,

Mapk8,

Agt and

Ifi27. These results are corroborated by multiple studies indicating how various polymicrobial interactions [

41] and adaptive and innate immune response [

42] can ameliorate or worsen IBD symptoms. In particular, our data are in agreement with a study by Wurbel

et al. [

43] which highlighted a strong correlation between

Ccr9 expression and amelioration of DSS-induced colitis symptoms. Specifically, their results showed that CCR9 knockout mice were more susceptive to DSS-induced colitis compared to wild type controls, and that a dysregulated Th-17 immune response involving different macrophage subsets was observed during their recovery period following DSS treatment.

Conversely, a previous study by Heimerl

et al. [

44] indicated that, in contrast to our data, the expression of the long chain acyl-CoA synthetase (ACSL) 1 protein was significantly upregulated in inflamed colon biopsies of IBD patients compared to biopsies collected from non-affected regions. This difference may be due to dissimilarities between human vs. mouse models, consequently reflecting diverse physiological functions.

Figure 1.

Candida (C.) tropicalis inoculation decreases susceptibility to chemical-induced colitis in C. albicans challenged- C57BL/6 mice. (A) Histological analysis shows decreased colonic inflammation in co-inoculated mice compared to mice challenged with C. albicans alone (unpaired t test, 13.75 ± 0.69 vs. 17.50 ± 1.36; P<0.05; N = 12/group), and increased colonic inflammation in C. albicans-challenged mice and C. tropicalis-challenged mice compared to the control group (unpaired t test, 17.50 ± 1.36 vs. 12.62 ± 0.93; P<0.02) (unpaired t test, 15.50 ± 0.95 vs. 12.62 ± 0.93; P<0.05). No statistical differences were found between co-inoculated mice and the control group (unpaired t test, 13.75 ± 0.69 vs. 12.62 ± 0.93; P = ns) and between co-inoculated mice and the C. tropicalis-inoculated group (unpaired t test, 13.75 ± 0.69 vs. 15.50 ± 0.95; P = ns). (B) Representative colonic histopathological sections of C. albicans- and C. tropicalis-inoculated mice show the presence of ulcers, active cryptitis, increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, and thicker intestinal mucosa compared to co-inoculated mice and the control group, showing minimal inflammatory cells and mild active cryptitis. (C) Colonoscopic evaluation shows increased colitis in the distal colon of mice challenged with C. albicans alone compared to co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 6.86 ± 0.22 vs. 6.27 ± 0.18; P < 0.05) and the control group (unpaired t test, 6.86 ± 0.22 vs. 5.87 ± 0.24; P < 0.02). No statistical differences were found between co-inoculated mice and the control group (unpaired t test, 6.27 ± 0.18 vs. 5.86 ± 0.24; P = ns) and between co-inoculated mice and the C. tropicalis-inoculated group (unpaired t test, 6.27 ± 0.18 vs. 6.67 ± 0.19; P = ns). (D) Narrow Band Imaging endoscopic pictures of the distal colon show higher presence of ulcers (red arrows) and colorectal bleeding (yellow arrows) in C. albicans-inoculated and C. tropicalis-inoculated mice compared to co-inoculated mice and the control group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and are representative of 2 separate experiments; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.02.

Figure 1.

Candida (C.) tropicalis inoculation decreases susceptibility to chemical-induced colitis in C. albicans challenged- C57BL/6 mice. (A) Histological analysis shows decreased colonic inflammation in co-inoculated mice compared to mice challenged with C. albicans alone (unpaired t test, 13.75 ± 0.69 vs. 17.50 ± 1.36; P<0.05; N = 12/group), and increased colonic inflammation in C. albicans-challenged mice and C. tropicalis-challenged mice compared to the control group (unpaired t test, 17.50 ± 1.36 vs. 12.62 ± 0.93; P<0.02) (unpaired t test, 15.50 ± 0.95 vs. 12.62 ± 0.93; P<0.05). No statistical differences were found between co-inoculated mice and the control group (unpaired t test, 13.75 ± 0.69 vs. 12.62 ± 0.93; P = ns) and between co-inoculated mice and the C. tropicalis-inoculated group (unpaired t test, 13.75 ± 0.69 vs. 15.50 ± 0.95; P = ns). (B) Representative colonic histopathological sections of C. albicans- and C. tropicalis-inoculated mice show the presence of ulcers, active cryptitis, increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, and thicker intestinal mucosa compared to co-inoculated mice and the control group, showing minimal inflammatory cells and mild active cryptitis. (C) Colonoscopic evaluation shows increased colitis in the distal colon of mice challenged with C. albicans alone compared to co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 6.86 ± 0.22 vs. 6.27 ± 0.18; P < 0.05) and the control group (unpaired t test, 6.86 ± 0.22 vs. 5.87 ± 0.24; P < 0.02). No statistical differences were found between co-inoculated mice and the control group (unpaired t test, 6.27 ± 0.18 vs. 5.86 ± 0.24; P = ns) and between co-inoculated mice and the C. tropicalis-inoculated group (unpaired t test, 6.27 ± 0.18 vs. 6.67 ± 0.19; P = ns). (D) Narrow Band Imaging endoscopic pictures of the distal colon show higher presence of ulcers (red arrows) and colorectal bleeding (yellow arrows) in C. albicans-inoculated and C. tropicalis-inoculated mice compared to co-inoculated mice and the control group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and are representative of 2 separate experiments; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.02.

Figure 2.

C. tropicalis alters the lymphocytic immunophenotype in C. albicans-challenged mice during dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis. Cultured lymphocytes collected from mesenteric lymph node displayed significant differences between C. albicans-inoculated mice, C. tropicalis-inoculated mice, co-inoculated mice and the control group: (A) decrease of interleukin (IL)-4 between C. albicans-inoculated mice and co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.072 ± 0.006 vs. 0.243 ± 0.068, P < 0.05) and the control group (unpaired t test, 0.072 ± 0.006 vs. 0.249 ± 0.060, P < 0.02); decrease of IL-4 between C. tropicalis-inoculated mice and co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.046 ± 0.009 vs. 0.243 ± 0.067, P < 0.02) and the control group (unpaired t test, 0.046 ± 0.009 vs. 0.249 ± 0.060, P < 0.02). (B) Decrease of IL-17 between C. tropicalis- and C. albicans-inoculated mice compared to co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.075 ± 0.022 vs. 0.532 ± 0.164, P < 0.02) (unpaired t test, 0.134 ± 0.014 vs. 0.532 ± 0.164, P < 0.05) and the control group (unpaired t test, 0.075 ± 0.022 vs. 0.550 ± 0.150, , P < 0.02) (unpaired t test, 0.134 ± 0.014 vs. 0.550 ± 0.150, P < 0.02). Lymphocytes do not display significant difference between co-inoculated mice and the control group in terms of IL-4 (unpaired t test, 0.243 ± 0.068 vs. 0.249 ± 0.060, P=ns) and IL-17 (unpaired t test, 0.532 ± 0.164 vs. 0.550 ± 0.150, P=ns). (C) Decrease of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) between C. albicans-inoculated mice and co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.833 ± 0.081 vs. 1.133± 0.107, P < 0.05); decrease of TNF between C. tropicalis-inoculated mice and co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.368 ± 0.044 vs. 1.133 ± 0.107, P < 0.001), C. albicans-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.368 ± 0.044 vs. 0.833 ± 0.081, P < 0.001) and the control group (unpaired t test, 0.368 ± 0.044 vs. 0.980 ± 0.053, P < 0.001). (D) Decrease of interferon (IFN)γ between C. tropicalis-inoculated mice and co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.700 ± 0.216 vs. 1.236 ± 0.083 vs. 1.218 ± 0.070, P < 0.05); increase of IFNγ between C. albicans-inoculated mice and the control group (unpaired t test, 0.988 ± 0.088 vs. 1.150 ± 0.745 vs. 0.043 ± 0.064, P < 0.05); increase of IFNγ between co-inoculated mice and the control group (unpaired t test, 1.218 ± 0.070 vs. 1.150 ± 0.130 vs. 0.745 ± 0.043, P < 0.001). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and are representative of 2 separate experiments; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.02, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

C. tropicalis alters the lymphocytic immunophenotype in C. albicans-challenged mice during dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis. Cultured lymphocytes collected from mesenteric lymph node displayed significant differences between C. albicans-inoculated mice, C. tropicalis-inoculated mice, co-inoculated mice and the control group: (A) decrease of interleukin (IL)-4 between C. albicans-inoculated mice and co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.072 ± 0.006 vs. 0.243 ± 0.068, P < 0.05) and the control group (unpaired t test, 0.072 ± 0.006 vs. 0.249 ± 0.060, P < 0.02); decrease of IL-4 between C. tropicalis-inoculated mice and co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.046 ± 0.009 vs. 0.243 ± 0.067, P < 0.02) and the control group (unpaired t test, 0.046 ± 0.009 vs. 0.249 ± 0.060, P < 0.02). (B) Decrease of IL-17 between C. tropicalis- and C. albicans-inoculated mice compared to co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.075 ± 0.022 vs. 0.532 ± 0.164, P < 0.02) (unpaired t test, 0.134 ± 0.014 vs. 0.532 ± 0.164, P < 0.05) and the control group (unpaired t test, 0.075 ± 0.022 vs. 0.550 ± 0.150, , P < 0.02) (unpaired t test, 0.134 ± 0.014 vs. 0.550 ± 0.150, P < 0.02). Lymphocytes do not display significant difference between co-inoculated mice and the control group in terms of IL-4 (unpaired t test, 0.243 ± 0.068 vs. 0.249 ± 0.060, P=ns) and IL-17 (unpaired t test, 0.532 ± 0.164 vs. 0.550 ± 0.150, P=ns). (C) Decrease of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) between C. albicans-inoculated mice and co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.833 ± 0.081 vs. 1.133± 0.107, P < 0.05); decrease of TNF between C. tropicalis-inoculated mice and co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.368 ± 0.044 vs. 1.133 ± 0.107, P < 0.001), C. albicans-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.368 ± 0.044 vs. 0.833 ± 0.081, P < 0.001) and the control group (unpaired t test, 0.368 ± 0.044 vs. 0.980 ± 0.053, P < 0.001). (D) Decrease of interferon (IFN)γ between C. tropicalis-inoculated mice and co-inoculated mice (unpaired t test, 0.700 ± 0.216 vs. 1.236 ± 0.083 vs. 1.218 ± 0.070, P < 0.05); increase of IFNγ between C. albicans-inoculated mice and the control group (unpaired t test, 0.988 ± 0.088 vs. 1.150 ± 0.745 vs. 0.043 ± 0.064, P < 0.05); increase of IFNγ between co-inoculated mice and the control group (unpaired t test, 1.218 ± 0.070 vs. 1.150 ± 0.130 vs. 0.745 ± 0.043, P < 0.001). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and are representative of 2 separate experiments; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.02, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

C. tropicalis and C. albicans co-colonization alters production of short-chain fatty acids by gut microbiome. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis indicates decreased levels of: (A) propionic acid in fecal samples of co-inoculated mice compared to mice challenged with C. albicans alone (unpaired t test: 259.6 ± 103.1 vs. 551.4 ± 78.18; P<0.05) or C. tropicalis only (unpaired t test: 259.6 ± 103.1 vs. 635.4 ± 55.45; P<0.02); no differences were found between co-inoculated mice and the control group (unpaired t test: 259.6 ± 103.1 vs. 533.8 ± 111.4; P=ns). (B) valeric acid in co-inoculated mice compared to mice challenged with C. albicans alone (unpaired t test: 5.653 ± 2.072 vs. 17.520 ± 4.983; P<0.05), C. tropicalis alone (unpaired t test: 5.653 ± 2.072 vs. 22.230 ± 3.480; P<0.02) or the control group (unpaired t test: 5.653 ± 2.072 vs. 27.060 ± 6.288; P<0.02). (C) heptanoic acid in co-inoculated mice compared to mice challenged with C. tropicalis alone (unpaired t test: 0.360 ± 0.023 vs. 0.540 ± 0.056; P<0.02). No differences were found between groups in terms of (D) butyric acid and (E) hexanoic acid (P = ns). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and are representative of 2 separate experiments; N > 6/group; * P<0.05, ** P<0.02.

Figure 3.

C. tropicalis and C. albicans co-colonization alters production of short-chain fatty acids by gut microbiome. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis indicates decreased levels of: (A) propionic acid in fecal samples of co-inoculated mice compared to mice challenged with C. albicans alone (unpaired t test: 259.6 ± 103.1 vs. 551.4 ± 78.18; P<0.05) or C. tropicalis only (unpaired t test: 259.6 ± 103.1 vs. 635.4 ± 55.45; P<0.02); no differences were found between co-inoculated mice and the control group (unpaired t test: 259.6 ± 103.1 vs. 533.8 ± 111.4; P=ns). (B) valeric acid in co-inoculated mice compared to mice challenged with C. albicans alone (unpaired t test: 5.653 ± 2.072 vs. 17.520 ± 4.983; P<0.05), C. tropicalis alone (unpaired t test: 5.653 ± 2.072 vs. 22.230 ± 3.480; P<0.02) or the control group (unpaired t test: 5.653 ± 2.072 vs. 27.060 ± 6.288; P<0.02). (C) heptanoic acid in co-inoculated mice compared to mice challenged with C. tropicalis alone (unpaired t test: 0.360 ± 0.023 vs. 0.540 ± 0.056; P<0.02). No differences were found between groups in terms of (D) butyric acid and (E) hexanoic acid (P = ns). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and are representative of 2 separate experiments; N > 6/group; * P<0.05, ** P<0.02.

Figure 4.

C. tropicalis negatively affects the virulence of C. albicans by impairing its ability to produce biofilm and adhere to the surface of the host. (A) Recovery of C. albicans and C. tropicalis from fecal samples of the co-inoculated mice and mono-inoculated mice. Shown are colony-forming unit (CFU) counts from stools weighed, homogenized and plated for counts on Sabouraud dextrose agar. CFU assays showed that C. albicans burden significantly decreased in co-inoculated mice compared to mice inoculated with C. albicans alone (unpaired t test: 4.958 ± 0.267 vs. 6.164 ± 0.109; P<0.001) and compared to C. tropicalis CFUs in the co-inoculated group (unpaired t test: 4.958 ± 0.267 vs. 5.912 ± 0.144; P<0.02). (B) Representative pictures of C. albicans and C. tropicalis recovery 24 hours after the last inoculum. (C) Immunohistochemical staining for C. albicans shows that C. albicans is more abundant and it is able to penetrate deeper in the epithelium and in the lamina propria (black arrows) of colon tissues collected from mice mono-inoculated with C. albicans compared to the co-inoculated group. Colon tissues of mice inoculated with C. tropicalis present no clearly positive stain. Panels: 20X and 40X magnification. (D) Effects of supernatant collected from C. tropicalis culture on C. albicans biofilm formation. (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl] 2H-tetrazoliumhydroxide assay results show that C. albicans treated with C. tropicalis-cultured supernatant produced less biofilm compared to untreated C. albicans (unpaired t test: 1.340 ± 0.111 vs. 1.810 ± 0.147; P<0.05), while C. tropicalis strain treated with C. albicans-cultured supernatant did not show any significant alteration related to biofilm production compared to untreated C. tropicalis (unpaired t test: 1.200 ± 0.374 vs. 1.300 ± 0.381; P=ns). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and are representative of 2 separate experiments; N > 10/group; * P<0.05, ** P<0.02, *** P<0.001.

Figure 4.

C. tropicalis negatively affects the virulence of C. albicans by impairing its ability to produce biofilm and adhere to the surface of the host. (A) Recovery of C. albicans and C. tropicalis from fecal samples of the co-inoculated mice and mono-inoculated mice. Shown are colony-forming unit (CFU) counts from stools weighed, homogenized and plated for counts on Sabouraud dextrose agar. CFU assays showed that C. albicans burden significantly decreased in co-inoculated mice compared to mice inoculated with C. albicans alone (unpaired t test: 4.958 ± 0.267 vs. 6.164 ± 0.109; P<0.001) and compared to C. tropicalis CFUs in the co-inoculated group (unpaired t test: 4.958 ± 0.267 vs. 5.912 ± 0.144; P<0.02). (B) Representative pictures of C. albicans and C. tropicalis recovery 24 hours after the last inoculum. (C) Immunohistochemical staining for C. albicans shows that C. albicans is more abundant and it is able to penetrate deeper in the epithelium and in the lamina propria (black arrows) of colon tissues collected from mice mono-inoculated with C. albicans compared to the co-inoculated group. Colon tissues of mice inoculated with C. tropicalis present no clearly positive stain. Panels: 20X and 40X magnification. (D) Effects of supernatant collected from C. tropicalis culture on C. albicans biofilm formation. (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl] 2H-tetrazoliumhydroxide assay results show that C. albicans treated with C. tropicalis-cultured supernatant produced less biofilm compared to untreated C. albicans (unpaired t test: 1.340 ± 0.111 vs. 1.810 ± 0.147; P<0.05), while C. tropicalis strain treated with C. albicans-cultured supernatant did not show any significant alteration related to biofilm production compared to untreated C. tropicalis (unpaired t test: 1.200 ± 0.374 vs. 1.300 ± 0.381; P=ns). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and are representative of 2 separate experiments; N > 10/group; * P<0.05, ** P<0.02, *** P<0.001.

Figure 5.

C. tropicalis altered the expression of genes involved in multiple immune responses in C. albicans-challenged mice. Heatmaps of normalized data, indicating connections between genes differently expressed in colonic tissues of co-inoculated mice compared to mice mono-inoculated with A) C. tropicalis, B) C. albicans or C) the control group. Data are shown indicating associations between gene expression (gold, upregulation; blue, down regulation) and treatment. Each row corresponds to a specific probe and each column corresponds to a specific sample. Hierarchical clustering has been used to generate dendrograms. Volcano plots expressing NanoString data for 785 genes showed that colonic tissues of co-inoculated mice have (D) 12 genes upregulated compared to mice inoculated with C. tropicalis alone, (E) 1 gene down regulated and 6 genes upregulated compared to mice inoculated with C. albicans alone and (F) 21 genes upregulated compared to the control group. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments. * P < 0.05.

Figure 5.

C. tropicalis altered the expression of genes involved in multiple immune responses in C. albicans-challenged mice. Heatmaps of normalized data, indicating connections between genes differently expressed in colonic tissues of co-inoculated mice compared to mice mono-inoculated with A) C. tropicalis, B) C. albicans or C) the control group. Data are shown indicating associations between gene expression (gold, upregulation; blue, down regulation) and treatment. Each row corresponds to a specific probe and each column corresponds to a specific sample. Hierarchical clustering has been used to generate dendrograms. Volcano plots expressing NanoString data for 785 genes showed that colonic tissues of co-inoculated mice have (D) 12 genes upregulated compared to mice inoculated with C. tropicalis alone, (E) 1 gene down regulated and 6 genes upregulated compared to mice inoculated with C. albicans alone and (F) 21 genes upregulated compared to the control group. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments. * P < 0.05.