Submitted:

28 February 2024

Posted:

29 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Mapping the Mineral Composition of the Moon

2. Materials and Methods

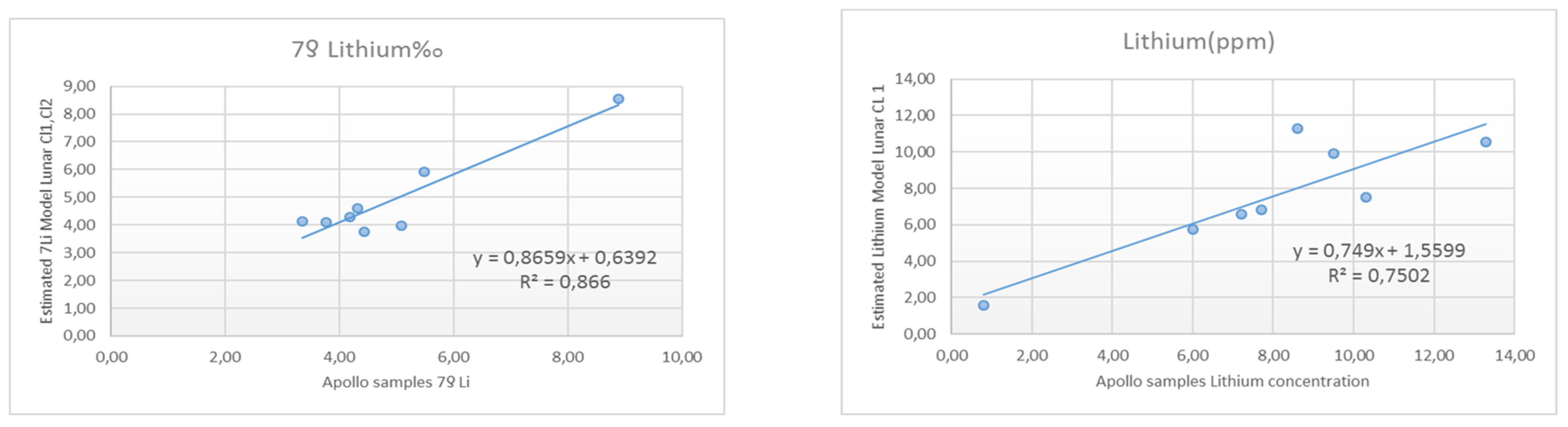

2.1. Lithium Exploration

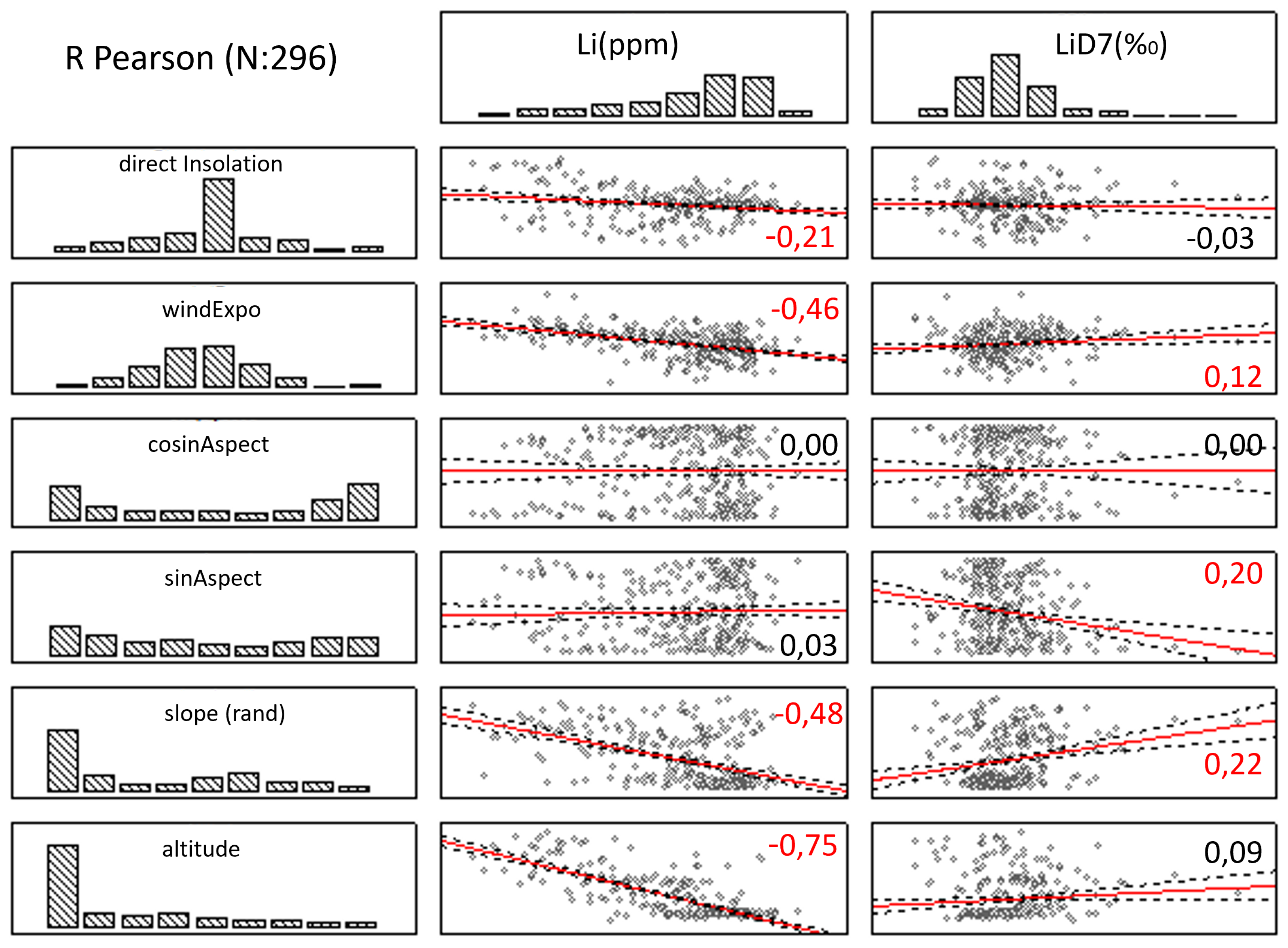

2.2. Lithium Distribution and Relief Patterns

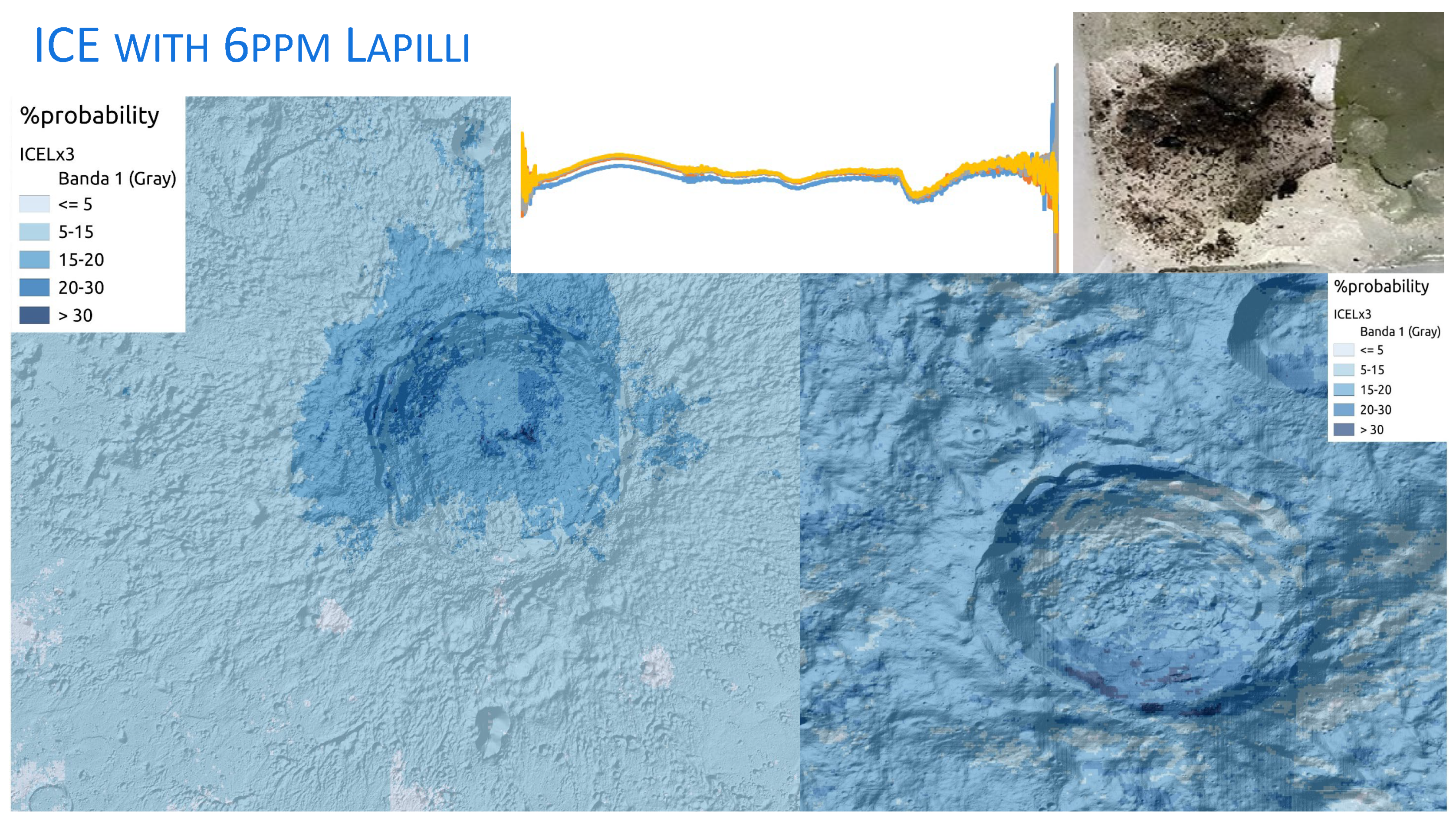

2.3. Dirty Ice

3. Results and Discussion

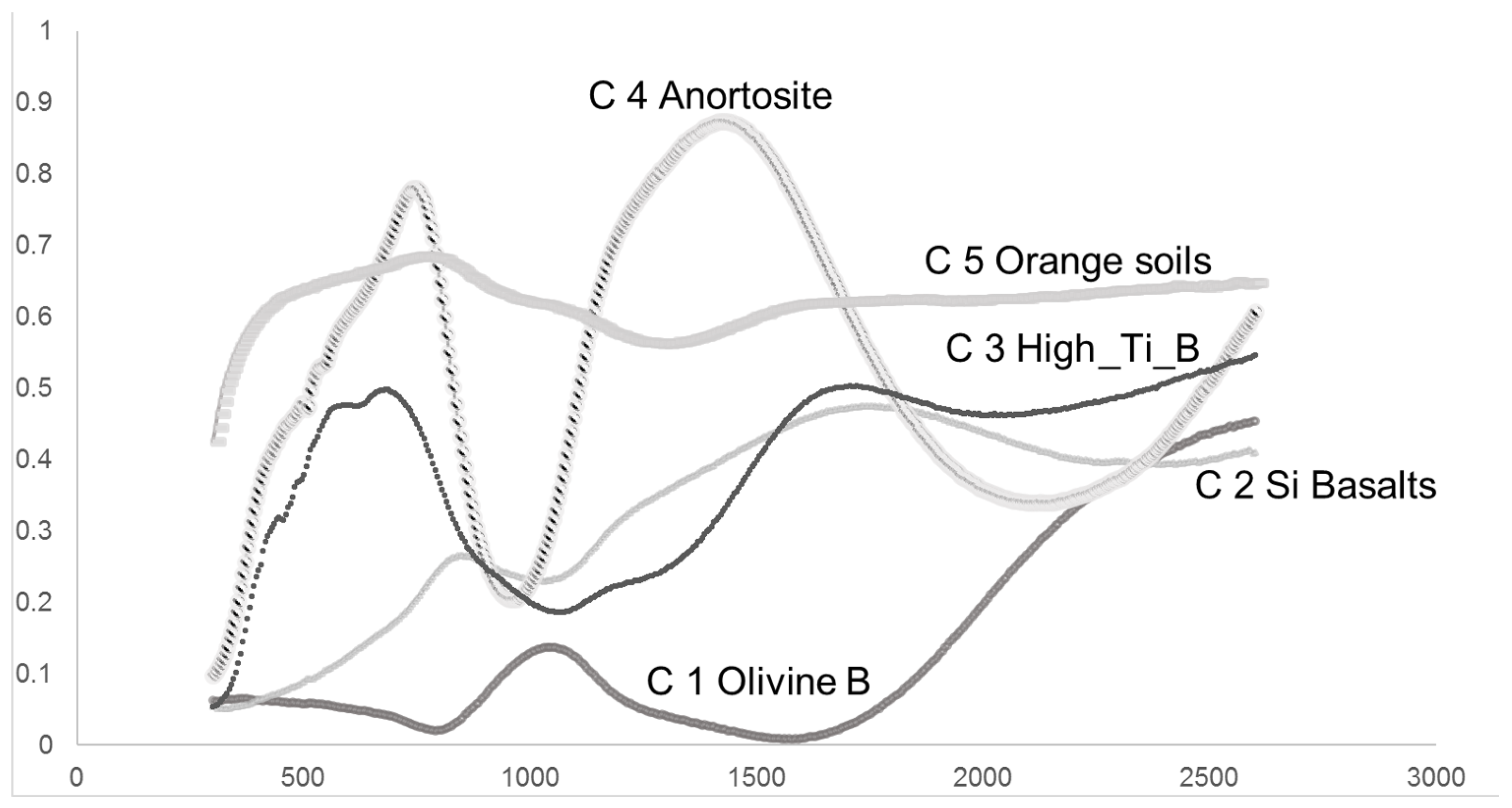

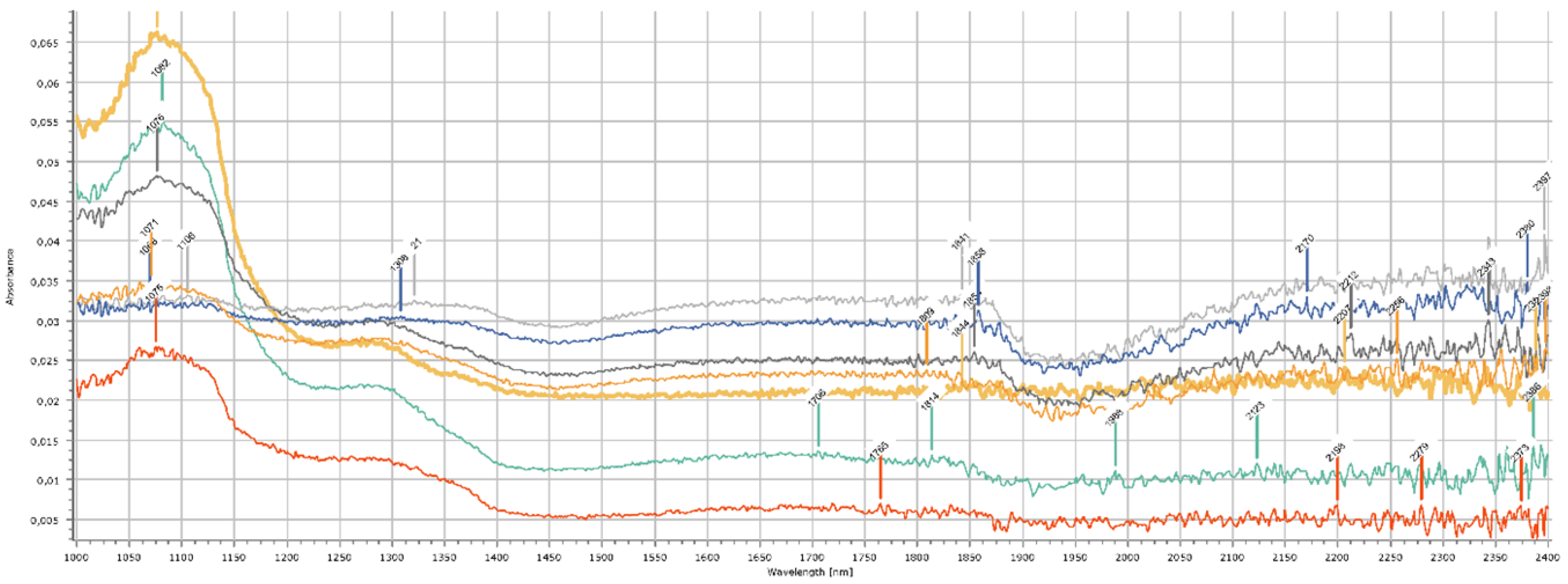

3.1. Types of Materials and Geological Samples

| R Pearson | Lithium (ppm) | 7 Li (‰) |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0.47 | 0.23 |

| C2 | -0.41 | -0.27 |

| C3 | -0.44 | -0.24 |

| C4 | 0.21 | 0.57 |

| C5 | 0.45 | 0.18 |

| ClemVis1 | -0.64 | 0.92 |

| ClemVis2 | -0.73 | 0.87 |

| ClemVis3 | -0.69 | 0.88 |

| ClemVis4 | -0.68 | 0.87 |

| ClemVis5 | -0.69 | 0.87 |

| ClemNir1 | -0.89 | 0.57 |

| ClemNir2 | -0.89 | 0.59 |

| ClemNir3 | -0.87 | 0.49 |

| ClemNir4 | -0.80 | 0.27 |

| ClemNir5 | -0.60 | -0.11 |

| ClemNir6 | -0.79 | 0.25 |

3.2. Linear Correlations between Clementine Bands, Spectral Ratios and Lithium Concentration

3.3. LRMs

| (a) Regression Summary for Dependent Variable: 7 Li(%o); R= 0.97333231; = 0.94737579; Adjusted = 0.90790763; p<0.0051; Std.Err 0.526 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Std.Err. | B | Std.Err | p-level | |

| Intercept | 2.615 | 2.010 | 0.263 | ||

| C4 | 0.623 | 0.226 | 8.924 | 3.243 | 0.051 |

| C5 | -0.495 | 0.204 | -7.468 | 3.082 | 0.073 |

| ClemVis1 | 0.736 | 0.137 | 60.845 | 11.337 | 0.006 |

| (b) Lithium(ppm) R= 0.95159092; = 0.90552528; Adjusted = 0.83466924; p<0.01620 Std.Err: 1.4782 | |||||

| Beta | Std.Err. | B | Std.Err | p-level | |

| Intercept | 64.760 | 20.821 | 0.036 | ||

| ClemNir1 | -7.233 | 3.581 | -672.392 | 332.918 | 0.114 |

| C5 | -0.539 | 0.251 | -74.410 | 34.623 | 0.098 |

| ClemNir2 | 6.106 | 3.501 | 536.480 | 307.561 | 0.156 |

3.4. Maps of Lithium and 7 Li

3.5. Relations with the DTMs

3.6. Dirty ice

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fisher, E.A.; Lucey, P.G.; Lemelin, M.; Greenhagen, B.T.; Siegler, M.A.; Mazarico, E.; Aharonson, O.; Williams, J.P.; Hayne, P.O.; Neumann, G.A.; others. Evidence for surface water ice in the lunar polar regions using reflectance measurements from the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter and temperature measurements from the Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment. Icarus 2017, 292, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayne, P.O.; Hendrix, A.; Sefton-Nash, E.; Siegler, M.A.; Lucey, P.G.; Retherford, K.D.; Williams, J.P.; Greenhagen, B.T.; Paige, D.A. Evidence for exposed water ice in the Moon’s south polar regions from Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter ultraviolet albedo and temperature measurements. Icarus 2015, 255, 58–69, Lunar Volatiles. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magna, T.; Wiechert, U.; Halliday, A.N. New constraints on the lithium isotope compositions of the Moon and terrestrial planets. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2006, 243, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtake, M.; Matsunaga, T.; Haruyama, J.; Yokota, Y.; Morota, T.; Honda, C.; Ogawa, Y.; Torii, M.; Miyamoto, H.; Arai, T.; others. The global distribution of pure anorthosite on the Moon. Nature 2009, 461, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, P.G. Mineral maps of the Moon. Geophysical Research Letters 2004, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaprete, A.; Schultz, P.; Heldmann, J.; Wooden, D.; Shirley, M.; Ennico, K.; Hermalyn, B.; Marshall, W.; Ricco, A.; Elphic, R.C.; others. Detection of water in the LCROSS ejecta plume. science 2010, 330, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charette, M.P.; McCord, T.B.; Pieters, C.M.; Adams, J.B. Application of Remote Spectral Reflectance Measurements to Lunar Geology Classification and Determination of Titanium Content of Lunar Soils. Journal of Geophysical Research 1974, 79, 1605–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, I.; Trombka, J.; Gerard, J.; Lowman, P.; Schmadebeck, R.; Blodget, H.; Eller, E.; Yin, L.; Lamothe, R.; Osswald, G.; others. Apollo 16 geochemical X-ray fluorescence experiment: Preliminary report. Science 1972, 177, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinyard, B.; Joy, K.; Kellett, B.; Crawford, I.; Grande, M.; Howe, C.; Fernandes, V.; Gasnault, O.; Lawrence, D.; Russell, S.; others. X-ray fluorescence observations of the Moon by SMART-1/D-CIXS and the first detection of Ti Kα from the lunar surface. Planetary and Space Science 2009, 57, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athiray, P.; Narendranath, S.; Sreekumar, P.; Dash, S.; Babu, B. Validation of methodology to derive elemental abundances from X-ray observations on Chandrayaan-1. Planetary and Space Science 2013, 75, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fa, W.; Zhu, M.H.; Liu, T.; Plescia, J.B. Regolith stratigraphy at the Chang’E-3 landing site as seen by lunar penetrating radar. Geophysical Research Letters 2015, 42, 10–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zuo, W.; Wen, W.; Zeng, X.; Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Su, Y.; Ren, X.; others. Overview of the Chang’e-4 mission: Opening the frontier of scientific exploration of the lunar far side. Space Science Reviews 2021, 217, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, A. Composition of the Moon as determined from orbit by gamma-ray spectroscopy, in Remote Geochemical Analysis: Elemental and Mineralogical Composition. Cambridge Univ. Press, New York 1993.

- Lawrence, D.; Feldman, W.; Barraclough, B.; Binder, A.; Elphic, R.; Maurice, S.; Thomsen, D. Global elemental maps of the Moon: The Lunar Prospector gamma-ray spectrometer. Science 1998, 281, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, D.; Feldman, W.; Barraclough, B.; Binder, A.; Elphic, R.; Maurice, S.; Miller, M.; Prettyman, T. Thorium abundances on the lunar surface. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2000, 105, 20307–20331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prettyman, T.H.; Hagerty, J.; Elphic, R.; Feldman, W.; Lawrence, D.; McKinney, G.; Vaniman, D. Elemental composition of the lunar surface: Analysis of gamma ray spectroscopy data from Lunar Prospector. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2006, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, M.; Hasebe, N.; Nagaoka, H.; Shibamura, E.; Ohtake, M.; Kim, K.; Wöhler, C.; Berezhnoy, A. Iron distribution of the Moon observed by the Kaguya gamma-ray spectrometer: Geological implications for the South Pole-Aitken basin, the Orientale basin, and the Tycho crater. Icarus 2018, 310, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elphic, R.; Lawrence, D.; Feldman, W.; Barraclough, B.; Maurice, S.; Binder, A.; Lucey, P. Lunar Fe and Ti abundances: comparison of Lunar Prospector and Clementine data. Science 1998, 281, 1493–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elphic, R.; Lawrence, D.; Feldman, W.; Barraclough, B.; Maurice, S.; Binder, A.; Lucey, P. Lunar rare earth element distribution and ramifications for FeO and TiO2: Lunar Prospector neutron spectrometer observations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2000, 105, 20333–20345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elphic, R.; Lawrence, D.; Feldman, W.; Barraclough, B.; Gasnault, O.; Maurice, S.; Lucey, P.; Blewett, D.; Binder, A. Lunar Prospector neutron spectrometer constraints on TiO2. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2002, 107, 8–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, W.; Barraclough, B.; Maurice, S.; Elphic, R.; Lawrence, D.; Thomsen, D.; Binder, A. Major compositional units of the Moon: Lunar Prospector thermal and fast neutrons. Science 1998, 281, 1489–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, W.; Lawrence, D.; Elphic, R.; Barraclough, B.; Maurice, S.; Genetay, I.; Binder, A. Polar hydrogen deposits on the Moon. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2000, 105, 4175–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, P.G.; Taylor, G.J.; Malaret, E. Abundance and distribution of iron on the Moon. Science 1995, 268, 1150–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucey, P.G.; Blewett, D.T.; Hawke, B.R. Mapping the FeO and TiO2 content of the lunar surface with multispectral imagery. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 1998, 103, 3679–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, P.G.; Blewett, D.T.; Jolliff, B.L. Lunar iron and titanium abundance algorithms based on final processing of Clementine ultraviolet-visible images. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2000, 105, 20297–20305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, P.G. Radiative transfer modeling of the effect of mineralogy on some empirical methods for estimating iron concentration from multispectral imaging of the Moon. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2006, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandfield, J.L.; Hayne, P.O.; Williams, J.P.; Greenhagen, B.T.; Paige, D.A. Lunar surface roughness derived from LRO Diviner Radiometer observations. Icarus 2015, 248, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Robinson, M.S.; Lawrence, S.J.; Denevi, B.W.; Hapke, B.; Jolliff, B.L.; Hiesinger, H. Lunar mare TiO2 abundances estimated from UV/Vis reflectance. Icarus 2017, 296, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Li, B.; Chen, S.; Lu, T.; Lu, P.; Lu, Y.; Jin, Q. Global estimates of lunar surface chemistry derived from LRO diviner data. Icarus 2022, 371, 114697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Bian, W.; Ren, X.; Mu, L.; Liu, J.; Li, C. Preliminary results of FeO mapping using Imaging Interferometer data from Chang’E-1. Chinese Science Bulletin 2011, 56, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Xiong, S.Q.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, L.; Gan, F.; Yang, S.; Wang, R. Mapping Lunar global chemical composition from Chang’E-1 IIM data. Planetary and Space Science 2012, 67, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xue, B.; Zhao, B.; Lucey, P.; Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Li, C.; Ouyang, Z. Global estimates of lunar iron and titanium contents from the Chang’E-1 IIM data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Chen, J.; Wu, Z.; Liu, J. Lunar iron and optical maturity mapping: Results from partial least squares modeling of Chang’E-1 IIM data. Icarus 2016, 280, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Jin, H.; Chen, X.; Yang, M.; Wu, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; others. New maps of lunar surface chemistry. Icarus 2019, 321, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, L.M.; Hunt, G.R.; Salisbury, J.W.; Balsamo, S.R. Compositional implications of Christiansen frequency maximums for infrared remote sensing applications. Journal of Geophysical Research 1973, 78, 4983–5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, J.W.; Basu, A.; Fischer, E.M. Thermal infrared spectra of lunar soils. Icarus 1997, 130, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, D.; Foote, M.; Greenhagen, B.; Schofield, J.; Calcutt, S.; Vasavada, A.; Preston, D.; Taylor, F.; Allen, C.; Snook, K.; others. The lunar reconnaissance orbiter diviner lunar radiometer experiment. Space Science Reviews 2010, 150, 125–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhagen, B.T.; Lucey, P.G.; Wyatt, M.B.; Glotch, T.D.; Allen, C.C.; Arnold, J.A.; Bandfield, J.L.; Bowles, N.E.; Hanna, K.L.D.; Hayne, P.O.; Song, E.; Thomas, I.R.; Paige, D.A. Global Silicate Mineralogy of the Moon from the Diviner Lunar Radiometer. Science 2010, 329, 1507–1509, [https://www.science.org/doi/pdf/10.1126/science.1192196]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, K.D.; Greenhagen, B.; Patterson Iii, W.; Pieters, C.; Mustard, J.; Bowles, N.; Paige, D.; Glotch, T.; Thompson, C. Effects of varying environmental conditions on emissivity spectra of bulk lunar soils: Application to Diviner thermal infrared observations of the Moon. Icarus 2017, 283, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, P.G.; Greenhagen, B.T.; Song, E.; Arnold, J.A.; Lemelin, M.; Hanna, K.D.; Bowles, N.E.; Glotch, T.D.; Paige, D.A. Space weathering effects in Diviner Lunar Radiometer multispectral infrared measurements of the lunar Christiansen Feature: Characteristics and mitigation. Icarus 2017, 283, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, P.G.; Hayne, P.O.; Costello, E.; Green, R.; Hibbitts, C.; Goldberg, A.; Mazarico, E.; Li, S.; Honniball, C. The spectral radiance of indirectly illuminated surfaces in regions of permanent shadow on the Moon. Acta Astronautica 2021, 180, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozette, S.; Rustan, P.; Pleasance, L.; Kordas, J.; Lewis, I.; Park, H.; Priest, R.; Horan, D.; Regeon, P.; Lichtenberg, C.; others. The Clementine mission to the Moon: Scientific overview. Science 1994, 266, 1835–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, A.; Robinson, M. Mapping of the Moon by Clementine. Advances in Space Research 1997, 19, 1523–1533, Proceedings of the BO.1 Symposium of COSPAR Scientific Commission B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, C.; Shkuratov, Y.; Kaydash, V.; Stankevich, D.; Taylor, L. Lunar soil characterization consortium analyses: Pyroxene and maturity estimates derived from Clementine image data. Icarus 2006, 184, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, C.M.; Hiroi, T. RELAB (Reflectance Experiment Laboratory): A NASA multiuser spectroscopy facility. Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, 2004, p. 1720.

- Dubayah, R.; Rich, P.M. Topographic solar radiation models for GIS. International journal of geographical information systems 1995, 9, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.P.; Gallant, J.C.; others. Digital terrain analysis. Terrain analysis: Principles and applications 2000, 6, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Olaya, V.; Conrad, O. Geomorphometry in SAGA. Developments in soil science 2009, 33, 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Böhner, J.; Antonić, O. Land-surface parameters specific to topo-climatology. Developments in soil science 2009, 33, 195–226. [Google Scholar]

- Papike, J.; Taylor, L.; Simon, S. Lunar minerals. Lunar sourcebook: A user’s guide to the Moon 1991, pp. 121–181.

- Blewett, D.T.; Hawke, B.R.; Lucey, P.G. Lunar pure anorthosite as a spectral analog for Mercury. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 2002, 37, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, P.H.; Shirley, D.N.; Kallemeyn, G.W. A potpourri of pristine Moon rocks, including a VHK mare basalt and a unique, augite-rich Apollo 17 anorthosite. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1986, 91, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, C.; Pratt, S. Earth-based near-infrared collection of spectra for the Moon: A new PDS data set. Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, 2000, p. 2059.

- Pieters, C.M.; Ammannito, E.; Blewett, D.T.; Denevi, B.W.; De Sanctis, M.C.; Gaffey, M.J.; Le Corre, L.; Li, J.Y.; Marchi, S.; McCord, T.B.; McFadden, L.A.; Mittlefehldt, D.W.; Nathues, A.; Palmer, E.; Reddy, V.; Raymond, C.A.; Russell, C.T. Distinctive space weathering on Vesta from regolith mixing processes. Nature 2012, 491, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapke, B. Space weathering from Mercury to the asteroid belt. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2001, 106, 10039–10073, [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2000JE001338]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernazza, P.; Binzel, R.; Rossi, A.; Fulchignoni, M.; Birlan, M. Solar wind as the origin of rapid reddening of asteroid surfaces. Nature 2009, 458, 993–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingue, D.L.; Chapman, C.R.; Killen, R.M.; Zurbuchen, T.H.; Gilbert, J.A.; Sarantos, M.; Benna, M.; Slavin, J.A.; Schriver, D.; Trávníček, P.M.; others. Mercury’s weather-beaten surface: Understanding Mercury in the context of lunar and asteroidal space weathering studies. Space Science Reviews 2014, 181, 121–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.B.; McCord, T.B. Optical properties of mineral separates, glass, and anorthositic fragments from Apollo mare samples. Proceedings of the Lunar Science Conference, vol. 2, p. 2183, 1971, Vol. 2, p. 2183.

- Pieters, C.M.; Head, J.; Sunshine, J.; Fischer, E.; Murchie, S.; Belton, M.; McEwen, A.; Gaddis, L.; Greeley, R.; Neukum, G.; others. Crustal diversity of the Moon: Compositional analyses of Galileo solid state imaging data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 1993, 98, 17127–17148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, S.; Nakamura, K.; Hamabe, Y.; Kurahashi, E.; Hiroi, T. Production of iron nanoparticles by laser irradiation in a simulation of lunar-like space weathering. Nature 2001, 410, 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.K.; Pieters, C.M.; Keller, L.P. An experimental approach to understanding the optical effects of space weathering. Icarus 2007, 192, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C., Jr.; McKay, D.; Anderson, D.; Butler, P., Jr. The source of sublimates on the Apollo 15 green and Apollo 17 orange glass samples. In: Lunar Science Conference, 6th, Houston, Tex., March 17-21, 1975, Proceedings. Volume 2.(A78-46668 21-91) New York, Pergamon Press, Inc., 1975, p. 1673-1699., 1975, Vol. 6, pp. 1673–1699.

- Butler, J., Jr.; Meyer, C., Jr. Sulfur prevails in coatings on glass droplets-Apollo 15 green and brown glasses and Apollo 17 orange and black/devitrified/glasses. Lunar and Planetary Science Conference Proceedings, 1976, Vol. 7, pp. 1561–1581.

- Day, J.M.; Walker, R.J.; James, O.B.; Puchtel, I.S. Osmium isotope and highly siderophile element systematics of the lunar crust. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2010, 289, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, S.; Pieters, C.M. Mineralogy of the lunar crust: Results from Clementine. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 1999, 34, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Blewett, D.T.; Lucey, P.G.; Hawke, B.R.; Jolliff, B.L. Clementine images of the lunar sample-return stations: Refinement of FeO and TiO2 mapping techniques. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 1997, 102, 16319–16325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguere, T.A.; Taylor, G.J.; HAWKE, B.R.; Lucey, P.G. The titanium contents of lunar mare basalts. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 2000, 35, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, M.; Wöhler, C.; Dhingra, D.; Thangjam, G.; Rommel, D.; Mall, U.; Bhardwaj, A.; Grumpe, A. Compositional studies of Mare Moscoviense: New perspectives from Chandrayaan-1 VIS-NIR data. Icarus 2018, 303, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| subtrata | sample | Lithium(ppm) | 7 Li | Li ratio (7/ppm) | spectral index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anortosite | 62255 | 0.8 | 8.89 | 11,11 | C4 |

| Basalt | 15058 | 7.7 | 3.76 | 0.49 | C2 |

| Basalt | 12045 | 9.5 | 4.43 | 0.47 | C2 |

| Basalt | 15475 | 7.2 | 3.35 | 0.47 | C2 |

| High-Ti Mare Basalt | 70035 | 8.6 | 5.09 | 0.59 | C3 |

| High-Ti Mare Basalt | 75075 | 10.3 | 5.48 | 0.53 | C3 |

| OlivineBasalt | 15555 | 6.0 | 4.32 | 0.72 | C1 |

| Orange and GlassesSoil | 74220 | 13.3 | 4.19 | 0.32 | C5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).