Submitted:

28 February 2024

Posted:

29 February 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Research Model

Participants

Data Collection Tool

Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- 1-

- Training programs for trainers should aim to improve their emotional intelligence and communication skills. Trainers should be trained in emotional management strategies and stress coping techniques and transfer these skills to athletes.

- 2-

- Trainers should set an example by supporting athletes and creating an environment of trust. Focusing on the personal development of athletes, they should consider individual differences and provide them with appropriate support.

- 3-

- Trainers should actively communicate with athletes and try to understand their emotional needs. They should show empathy and provide open communication channels to protect athletes’ emotional well-being and increase their motivation.

- 4-

- Sports clubs and federations should support the training and development of trainers. Training programs should aim to strengthen the leadership skills, communication skills, and psychological counseling competencies of trainers.

- 5-

- Trainers should emphasize sport’s ethical values and support the spirit of fair play.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sagar, S.S.; Jowet, S. Communicative acts in coach–athlete interactions: When losing competitions and when making mistakes in training. Western Journal of Communication 2012, 76, 148–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, T.; Ntoumanis, N.; Liukkonen, J. Motivational climate, goal orientation, perceived sport ability, and enjoyment within. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2016, 26, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avcı, K.S.; Çepikkurt, F.; Kale, E.K. Examination of the relationship between coach-athlete communication levels and perceived motivational climate for volleyball players. Universal Journal of Educational Research 2018, 6, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallett, C.J. Modelling the Complexity of the coaching process: A commentary. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching 2007, 2, 407–409. [Google Scholar]

- Jowett, S.; Poczwardowski, A. Understanding the coach-athlete relationship. In Social Psychology in Sport, 1st ed.; Jowett, S, Lavallee, D, Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2007; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, R. Positive Cooaching, Motivation and Communication. ResearchStudy For The Study of Young Sports. Michigan State University 2003; https://slideplayer.com/slide/5177545/.

- Danilewicz, C. Violence in Youth Sport: Potential Preventative Measures and Solutions. UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Kavussanu, M.; Stanger, N.; Boardley, I.D. The Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviour in Sport Scale: Further evidence for construct validity and reliability. Journal of Sports Sciences 2013, 31, 1208–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, J. Anger rumination: an antecedent of athlete aggression? Psychologist. Sports Exercise 2004, 5, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İkizler, C.; Karagözoğlu, C. Psychology of Success in Sports (In Turkish: Sporda Başarının Psikolojisi). 3rd ed.; Alfa Basım Yayım Dağıtım, İstanbul, 1997.

- Fields, S.; Collins, C.L.; Comstock, R.D. Violence in youth sports: Hazing, brawling and foul play. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2010, 44, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gönen, M. The Effect of Coach-Athlete Relationship on Athletes’ State Anxiety, Anger and Subjective Well-Being Levels: Taekwondo and Protective Football Example. Doctoral Thesis, T.C. Gazi University Institute of Health Sciences, Ankara, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sevim, Y. Training Science (In Turkish; Antrenman Bilgisi). Nobel Yayın Dağıtım, Ankara, 2002.

- Dosil, J. The Sport Psychologist’s Handbook: A Guide for Sport-Specific Performance Enhancement, John Wiley Press, San Francisco, 2005; 24.

- Karasar, N. Scientific Research Method (In Turkish: Bilimsel Araştırma Yöntemi). Nobel, Ankara, 2012.

- Filiz. B.; Demirhan, G. Adaptation of the coaching behavior assessment questionnaire into the Turkish culture. Spormetre 2017, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, B.; Kural, S.; Özbek, O. Competitive aggressiveness and anger scale: validity and reliability study. Sportif Bakış: Spor ve Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi. 2019, 6, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Korucuk, M. A distance education attitude scale: A validity and reliability study. Millî Eğitim Dergisi, 2023, 52, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, D. Confirmatory factor analysis. Oxford University Press. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Büyüköztürk, Ş. Manual of data analysis for social sciences (In Turkish: Sosyal Bilimler için Veri Analizi El Kitabı). Pegem Akademi Yayınları, Ankara, 2010.

- Korucuk, N. Consumer purchasing behavior on green products in the context of green marketing. Master Thesis, Kafkas University, Institute of social sciences, Department of business of administration. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, H.M.J.; O’neıl, R.T.; Bauer, P.; Kohne, K. The behavior of the p-value when alternative hypothesis is true? Biometrics, 1997, 53, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual, Anı Yayıncılık, Ankara, 2017.

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics (6th ed.), Allyn and Bacon, Boston, 2013.

- Kalkan, T.; Sarı, İ. Coaching behaviors: theoretical approaches, coaches’ effect on athletes and recommendations. Review Article Journal of Exercise and Sport Sciences Research 2021, 1, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Moiratidou, K. Determinants of athletes’ moral competence: The role of demographic characteristics and sport-related perceptions. Sport in Society 2017, 20, 802–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayılmaz, A. Psychological and Social Reasons That Make The Amateur Players of Show Agressive Behaviours (Zonguldak Super Amateur League Sample). Master Thesis, . Sakarya University Insitute of Social Sciences, Sakarya, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tutkun, E.; Güner, B.Ç.; Ağaoğlu, S.A.; Soslu, R. Evaluation of aggression levels of individuals participating in team and individual sports. Spor ve Performans Araştırmaları Dergisi, 2010, 1, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

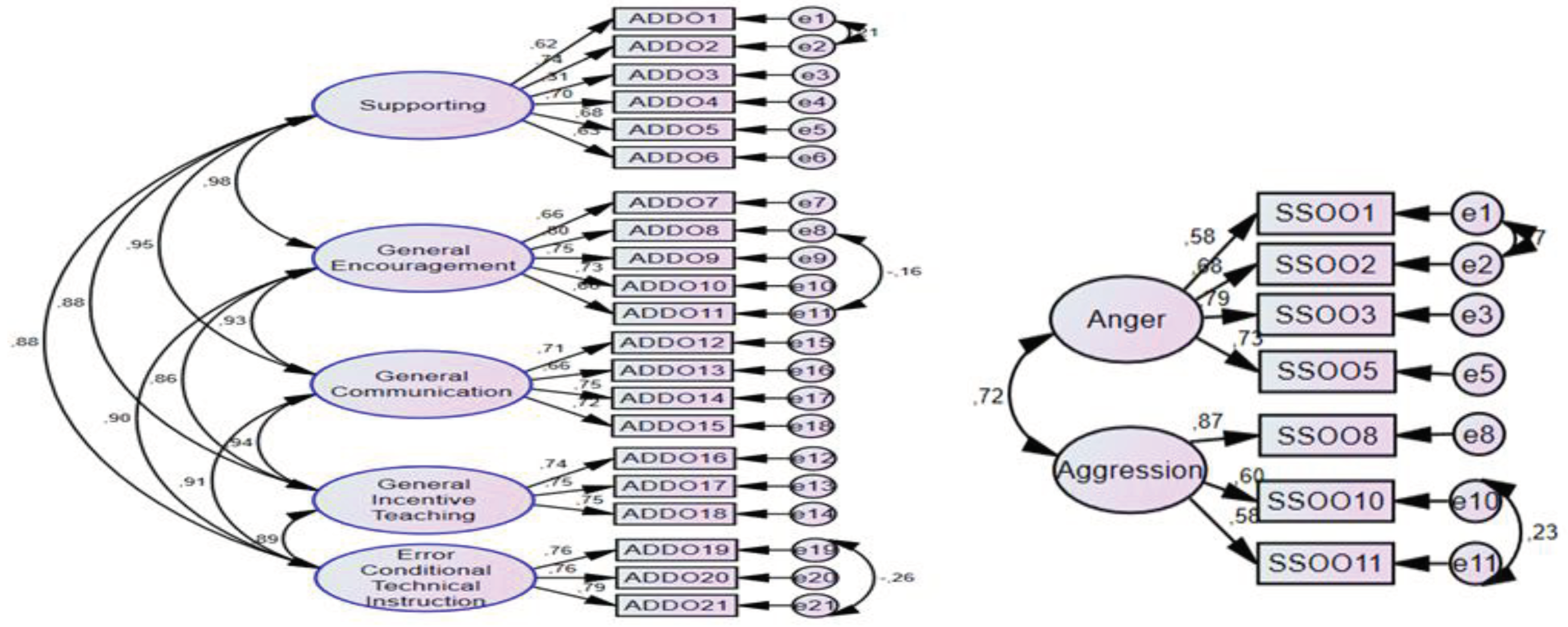

| Fit Indices | Reference Range | Results | Evaluation | |||

| Good | Acceptable | CAAS | CBAQ | CAAS | CBAQ | |

| CMIN/DF | 0<χ2/sd≤3 | 3<χ2/sd≤5 | 3.600 | 4.815 | Acceptable | Acceptable |

| RMSEA | 0≤RMSEA≤.05 | .05≤RMSEA≤ .08 | .059 | .071 | Acceptable | Acceptable |

| GFI | .90<GFI≤1 | .85<GFI≤.90 | .985 | .904 | Good | Good |

| AGFI | .90<GFI≤1 | .85<GFI≤.90 | .962 | .874 | Good | Acceptable |

| CFI | .95<CFI≤1 | .90<CFI≤.94 | .984 | .922 | Good | Acceptable |

| RMR | 0≤RMR≤.05 | 0.05≤SRMR≤.10 | .039 | .042 | Good | Good |

| TLI | .95<TLI≤1 | .90<TLI≤.94 | .970 | .907 | Good | Acceptable |

| DF | 11 | 176 | ||||

| CMIN | 39.595 | 847.366 | ||||

| Cronbach’s Alfa-α | .83 | .95 | Highly Reliable | |||

| Variables | n | X̄ | ss | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| CBAQ | 748 | 3.99 | 0.73 | -0.471 | -0.907 |

| CAAS | 748 | 2.38 | 0.86 | 0.306 | -0.331 |

| CBAQ Encouragement dimension | 748 | 4.02 | 0.88 | -0.527 | -0.689 |

| CBAQ General Encouragement dimension | 748 | 4.14 | 0.92 | -0.883 | 0.197 |

| CBAQ General Encouragement Instruction | 748 | 4.11 | 0.91 | -0.806 | 0.063 |

| CBAQ General Communication dimension | 748 | 4.07 | 0.92 | -0.826 | -0.137 |

| CBAQ Mistake-Contingent Tech. Inst. | 748 | 4.06 | 0.99 | -0.886 | 0.083 |

| CAAS Anger Dimension | 748 | 2.09 | 0.87 | 0.797 | 0.485 |

| CAAS Aggressiveness Dimension | 748 | 2.38 | 1.03 | 0.070 | -0.944 |

| Scales/Sub-Dimensions | 1 | 1.a | 1.b | 1.c | 1.d | 1.e | 2. | 2.a | 2.b |

| 1.CBAQ | 1 | ||||||||

| 1.a- E | 0.894** | 1 | |||||||

| 1.b-GE | 0.869** | .758** | 1 | ||||||

| 1.c-GET | 0.814** | .712** | .674** | 1 | |||||

| 1.d-GC | 0.849** | .691** | .661** | .675** | 1 | ||||

| 1.e-MCTI | 0.827** | .670** | .701** | .637** | .696** | 1 | |||

| 2.CAAS | -0.255** | -.185** | -.262** | -.153** | -.227** | -.223** | 1 | ||

| 2.a. AA | -0.279** | -0.223** | -0.276** | -0.185** | -.247** | -.224** | .887** | 1 | |

| 2.b-AAG | -.191** | -.122** | -.205** | -.100** | -.172** | -.185** | .922** | .640** | 1 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | f | p |

| Regression | 48.390 | 5 | 9.678 | 13.859 | .000a |

| Residual | 518.160 | 742 | 0.698 | ||

| Total | 566.550 | 747 |

| Variable | B | Standard ErrorB | Standardized (β) | t | p |

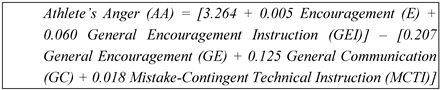

| Fixed | 3.264 | .159 | - | 20.486 | .000 |

| E dimension | .005 | .061 | .005 | .075 | .940 |

| GE dimension | -.207 | .057 | -.220 | -3.663 | .000 |

| GEI dimension | .060 | .053 | .063 | 1.145 | .253 |

| GC dimension | -.125 | .053 | -.133 | -2.365 | .018 |

| MCTI dimension | -.018 | .049 | -.020 | -.365 | .715 |

| R = 0.292, R2 = 0.085 F (5, 742)=13.859, p = .000 | |||||

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| Regression | 46.115 | 5 | 9.223 | 9.010 | .000a |

| Residual | 759.537 | 742 | 1.024 | ||

| Total | 805.652 | 747 | |||

| a. Predictor variables: The E, GE, GEI, GC, and MCTI dimensions of CBAQ b. Predicted variables: Athlete’s anger dimension of CAAS | |||||

| Variable | B | Standard Error B | Standardized (β) | t | p |

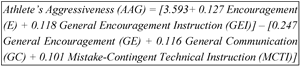

| Fixed | 3.593 | .193 | - | 18.626 | .000 |

| E dimension | .127 | .074 | .108 | 1.723 | .085 |

| GE dimension | -.247 | .069 | -.220 | -3.607 | .000 |

| GEI dimension | .118 | .064 | .104 | 1.846 | .065 |

| GC dimension | -.116 | .064 | -.103 | -1.807 | .071 |

| MCTI dimension | -.101 | .059 | -.097 | -1.717 | .086 |

| R =0.239 R2 = 0.057 F (5. 742)= 9.010 p = .000 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).