3.1. Experimental Principle

If the theory holds, expanding upon the previously posited theory that electromagnetic waves originate from the vibrational motion of a homogeneous string and integrating it with the intrinsic properties of electromagnetic waves, one can deduce that the energy associated with one oscillation cycle of an electromagnetic wave is a constant value. Considering equation (9), which represents the constant tension T in the string, it follows that the length of the string for one oscillation cycle, denoted as 'L,' is also constant. In the state of transverse vibration, the length of the string must surpass the wavelength. The bending speed of the string must be greater than the wave speed. Consequently, when generating transverse vibrations for electromagnetic waves, the bending speed of the string must exceed the speed of light. As the frequency of electromagnetic waves increases, the bending speed of the string inevitably increases, and the amplitude will also increase in the absence of boundaries.

Based on the wavelength of electromagnetic waves , where is the speed of light and is the frequency, when the frequency is 2HZ, the wavelength , and is the distance light travels per second (approximately 3×10⁸ meters). Therefore, the string length for one vibration cycle of an electromagnetic wave must be greater than and fixed. Taking an electromagnetic wave with a wavelength of 355 nm as an example, under boundary-free conditions, its quarter-period is approximately , corresponding to a quarter of the string length m and an amplitude . Calculations show that the time required for a mass point to move from the equilibrium position to the antinode over a distance is less than , and the smaller the deviation from the equilibrium position, the shorter this time. The average speed of movement already exceeds times the speed of light. If equipment with a time-resolution limit of s is used to measure the time difference for the vibration to reach this equilibrium position and the antinode, the equipment cannot display any time difference. Detailed calculations and explanations are provided in Appendix A.1. The time difference for completing the entire vibration cycle is also indistinguishable and can be considered instantaneous. For descriptive convenience, the phenomenon where electromagnetic wave energy instantaneously reaches positions within the transverse amplitude range from the vibration equilibrium position—under measurement equipment with a time-resolution limit of s—is hereafter termed the transverse instantaneous phenomenon. Here, "instantaneous" refers to the illusory instantaneity resulting from insufficient time resolution of the equipment.

3.2. Experimental Design

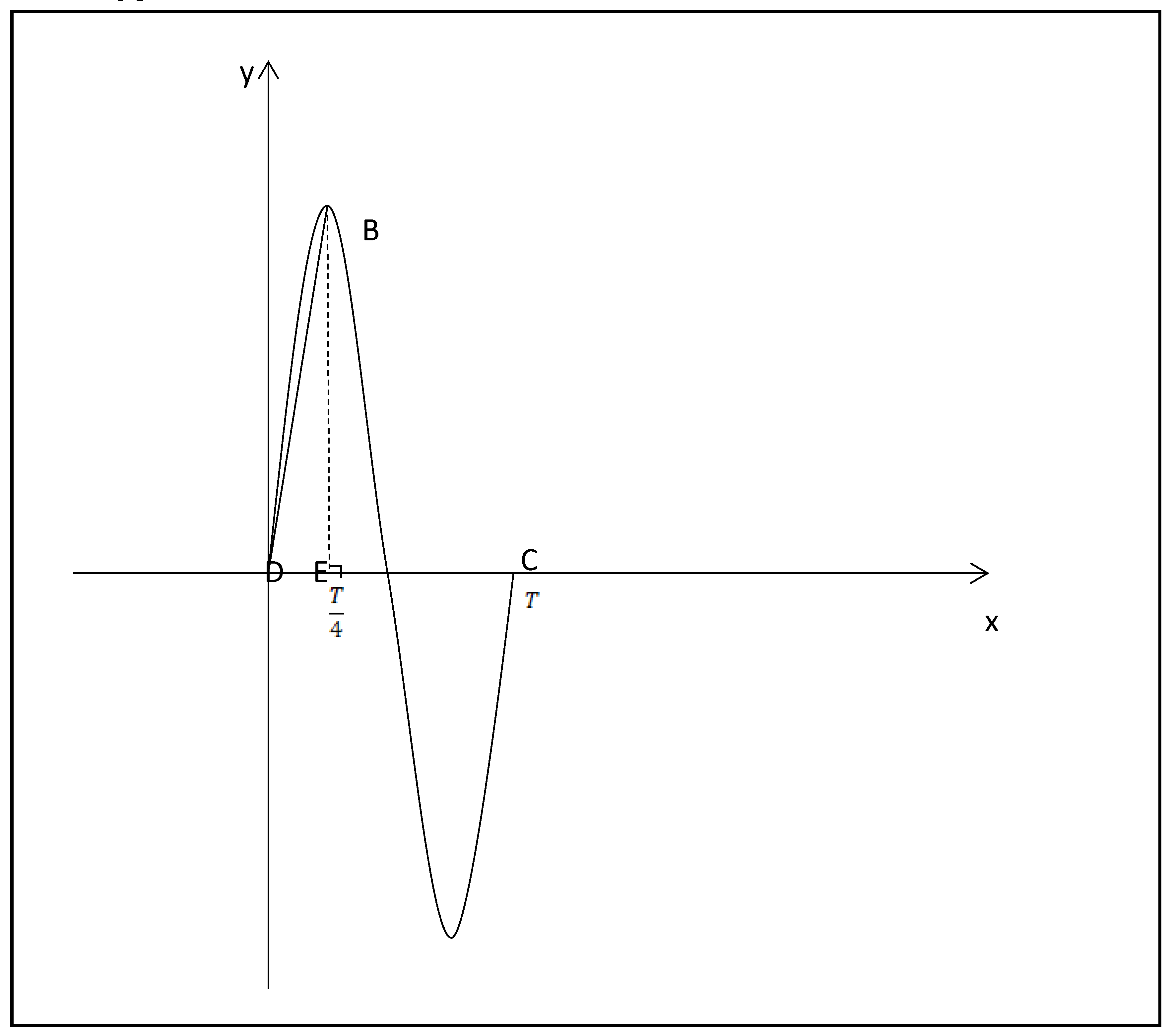

Figure 1a is a top-view schematic diagram. A pulsed laser emits 355nm wavelength pulsed laser light propagating in the direction of the arrow. AB represents the path of the vibration equilibrium position, and CE⊥AB. If electromagnetic waves are waves formed by string vibration, under boundary-free conditions, they will generate the string vibration wave shown in the diagram. Point C is the area where the photodetector (PMT) receives the optical signal, and the length CE is less than the amplitude of the string vibration wave. When the electromagnetic wave propagates from point A to point E, the vibration will reach point C in less than

s, at which point the photodetector will receive the optical signal. If a light-blocking plate is added between the detector and AB as shown in

Figure 1b, the string vibration will collide with the plate, resulting in a reduced amplitude. In this case, the detector will not receive the optical signal. Since the string length is fixed within one vibration cycle, a string of fixed length will be compressed within one wavelength. The closer the collision is to the equilibrium position, the denser the string lines become at the equilibrium position, and the corresponding energy density should increase. Observing a laser beam in air reveals that the light spot is the brightest. If the spot diameter is reduced and the divergence angle is controlled, treating the spot as a point and its path as a line in the experiment, then the light spot path can represent the equilibrium position path of the light spot’s path light vibration.

Since boundary-free conditions correspond to a perfect vacuum in the real universe, which is difficult to achieve artificially, the experiment was conducted in air at room temperature and pressure. Due to the gaps between air molecules, this space can approximate a perfect vacuum environment when no other microscopic particles are present. If electromagnetic waves are waves formed by string vibration, when the single-pulse energy is sufficiently large, after experiencing energy attenuation, some vibrating string lines should be able to avoid a portion of the air molecules, pass through the intermolecular gaps, and generate a transverse instantaneous phenomenon within a certain range deviating from the equilibrium position.

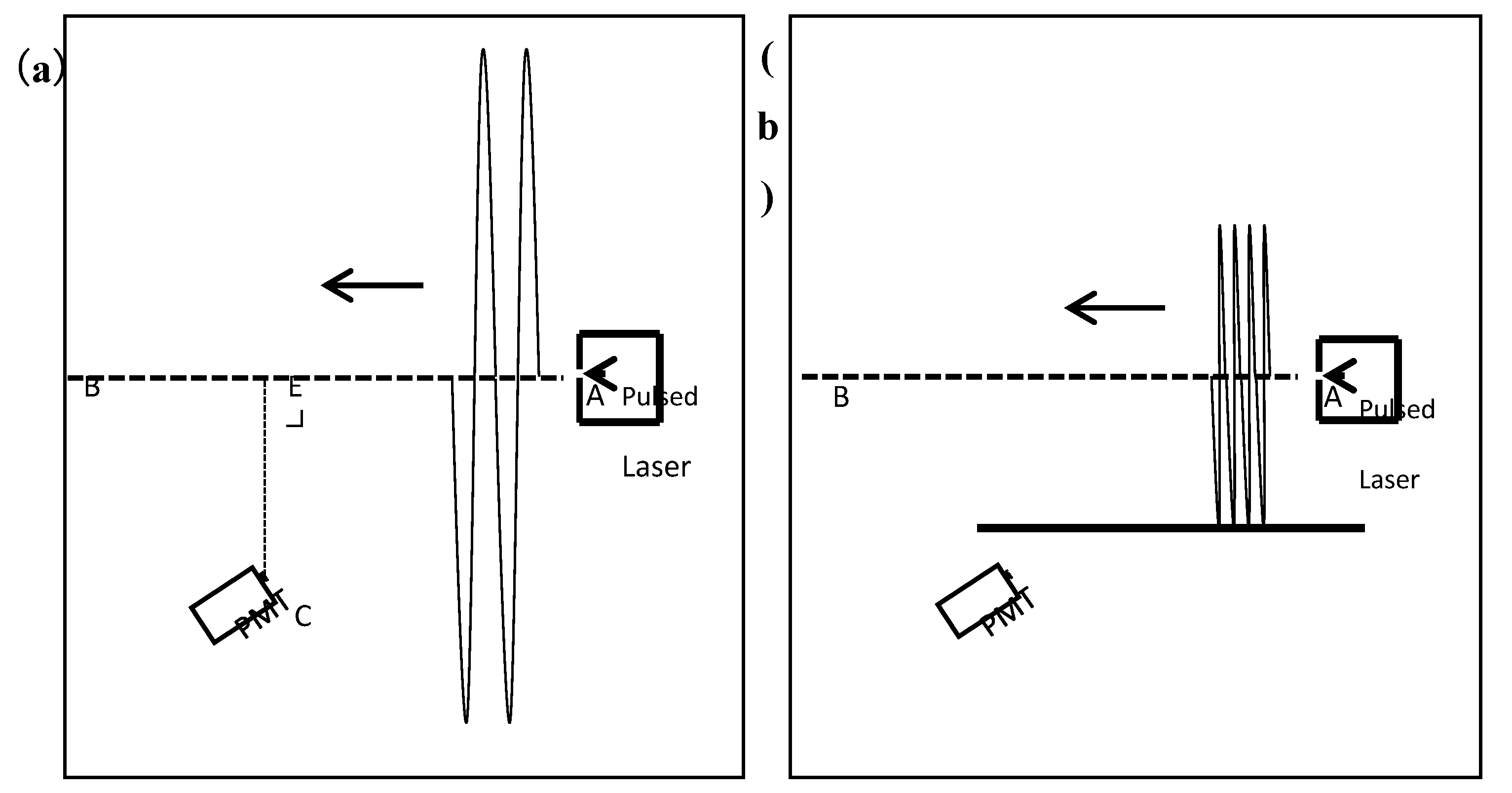

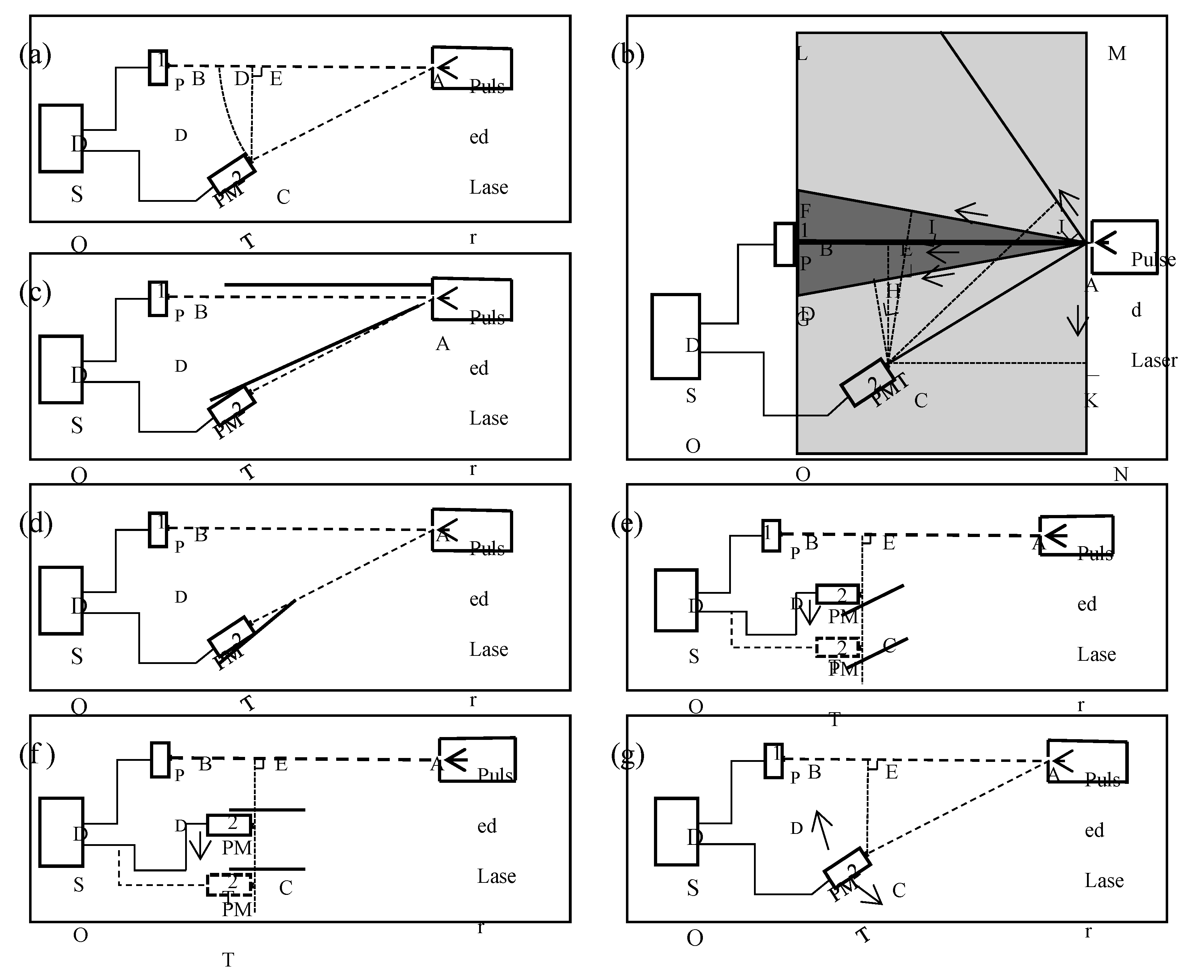

This article only studies one-dimensional plane waves. The experimental setup is connected as shown in

Figure 2a (top-view schematic). The pulsed laser can emit 355nm pulsed laser light in the direction of the arrow. Detector PD1 and Detector PMT2 are two photodetectors that convert received optical signals into electrical signals transmitted via BNC cables to a digital storage oscilloscope (DSO) (with a measurement time resolution limit of

s). The DSO can display electrical signal waveforms: the signal from detector 1 connected to channel CH1 produces waveform 1, and the signal from detector 2 connected to channel CH2 produces waveform 2. With fixed cable lengths, comparing changes in the rising edge time difference between the two signal waveforms can reflect changes in the time difference of the optical signals arriving at detectors 1 and 2. EC⊥AB, AD=AC. Points B and C are the optical signal reception areas for detectors 1 and 2, respectively. Point A is the light exit aperture, and AB is the central path of the light spot.

Since the laser emits multiple photons simultaneously, and pulsed laser propagation in air experiences divergence and scattering (light exhibiting the transverse instantaneous phenomenon will be specifically mentioned later; otherwise, light follows conventional theory by default), it is impossible to produce light propagating in only one direction. Under real experimental conditions in air, the emitted light should appear as shown in

Figure 2b,

m. Triangle AFG represents a portion of the divergent light region, and rectangle LMNO represents a portion of the scattered light region. After emission in these multiple directions, during propagation without collisions, theoretically, light in all directions should exhibit the transverse instantaneous phenomenon.

Figure 2b depicts several representative light ray directions: AJ and AN are scattered light, AF and AG are divergent light, and AB is the central beam of the light spot. When light in the scattered light region along direction AJ propagates to point J, detector 2 can capture the optical signal (a time difference less than

s is considered instantaneous). Similarly, detector 2 can capture the optical signal when light along directions AF, AB, AG, and AN propagates to points I, E, H, and K, respectively.

However, air contains numerous molecules, and emitted light collides with them. Observing the laser beam reveals that light deviating from the spot path experiences significant energy attenuation, with brightness decreasing as deviation increases. The observed laser spot diameter in this experiment is 2mm with a clear contour. If the hypothesis that electromagnetic waves are waves formed by string vibration holds, then after emission in air, most energy should be concentrated within 2mm around the vibration equilibrium position. Light forming the transverse instantaneous phenomenon with amplitudes exceeding 2mm should also be significantly attenuated. Furthermore, because greater deviation requires the vibrating string to avoid more molecules, the density of string lines penetrating intermolecular gaps decreases with increasing distance from the equilibrium position, leading to lower energy density. Scattered and divergent light should follow the same pattern. Scattered light has already undergone one significant attenuation relative to light on the spot path, and forming the transverse instantaneous phenomenon requires a second substantial attenuation. Light on the spot path forming the transverse instantaneous phenomenon only undergoes one significant attenuation. Therefore, by controlling the sensitivity of detector 2 and the voltage trigger threshold of the oscilloscope, the low-energy light components attenuated twice can be filtered out, only retaining scattered light and transverse instantaneous phenomenon light formed by spot path light, both of which have undergone only a single attenuation. Transverse instantaneous phenomenon light generated by divergent light can be filtered by controlling the divergence angle to reduce its intensity and adjusting the detector position to increase the deviation distance. Thus, with the equipment arranged as shown in

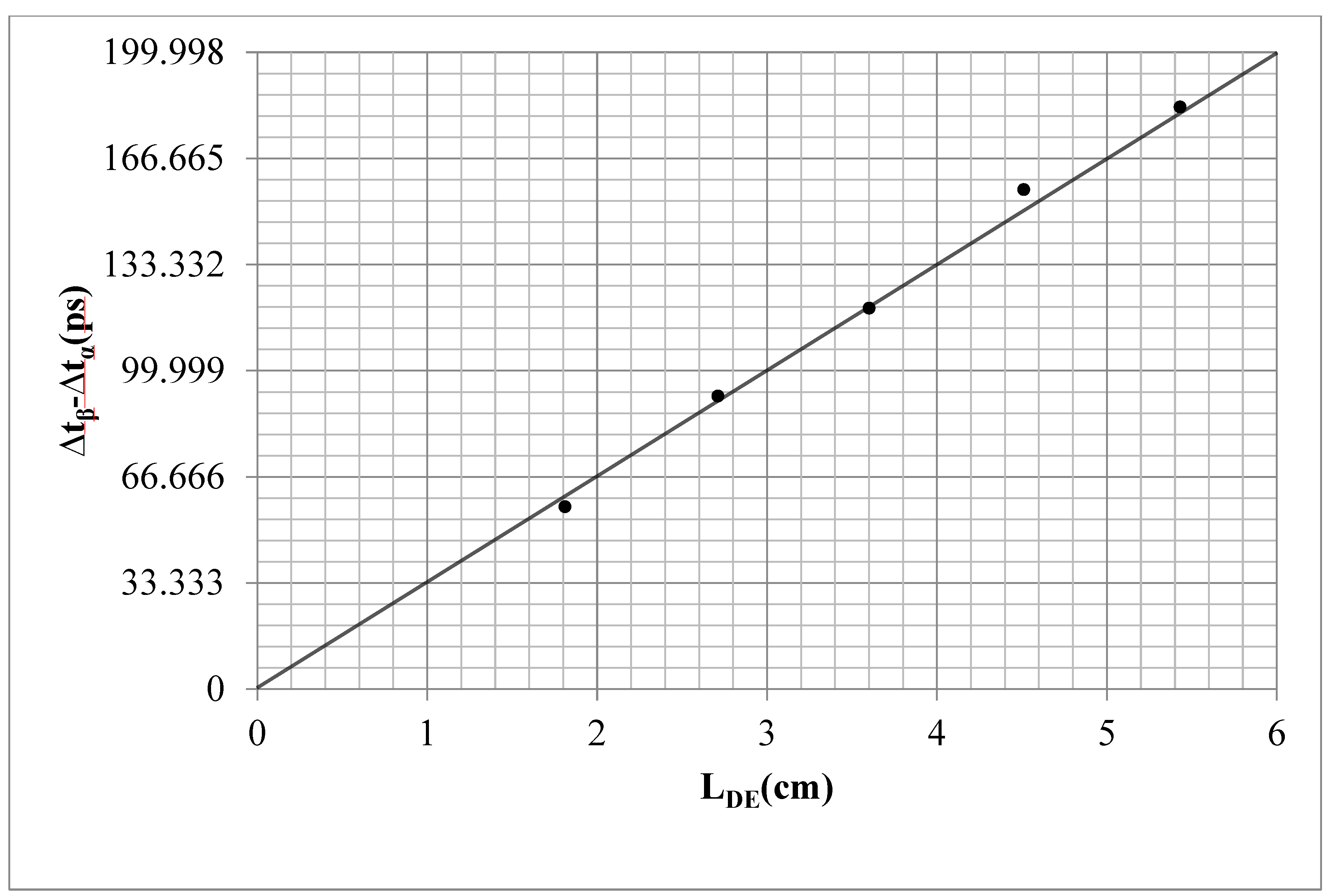

Figure 2a, waveform 2 can be formed solely by the combined effect of the transverse instantaneous phenomenon light from the central spot path and scattered light (the original emitted light spot width in this experiment was 2 mm, with a divergence angle less than 1°,within the allowable error tolerance, the original light spot path can be regarded as a straight line, hereinafter, it will be uniformly referred to as the central light spot path). The shortest time for the optical signal to reach detector 2 is

, and to reach detector 1 is

, where

is the distance and

c is the speed of light. The rising edge time difference between waveforms 1 and 2 detected by the oscilloscope is recorded as

. If, as shown in

Figure 2c, light-blocking plates are added between detector 2 and AB, and above AB, causing the vibrating string to collide prematurely, then the transverse instantaneous phenomenon light cannot reach detector 2. All other conditions remain unchanged. The shortest time for the optical signal to reach detector 2 becomes

(most scattered light energy should be concentrated within 2mm deviation from the equilibrium position; within the experimental error tolerance of this paper, the effect of a 2mm deviation on the signal arrival time at detector 2 is negligible). The time for the optical signal to reach detector 2 is delayed, while the time to reach detector 1 remains

. The rising edge time difference between waveforms 1 and 2 detected by the oscilloscope is now recorded as

. The change in time difference after adding the plates compared to before adding them should be