Submitted:

27 February 2024

Posted:

27 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

2.1. The Concept of SoS Evolution

2.2. Guiding Principles for SoS Evolution

2.2.1. Facilitate Information Exchange

2.2.2. Implementing Uniform Standards

2.2.3. Enhancing Transparency of Information

2.2.4. Establishing Common Goals

2.3. Agent-Based Modeling

3. Methodology

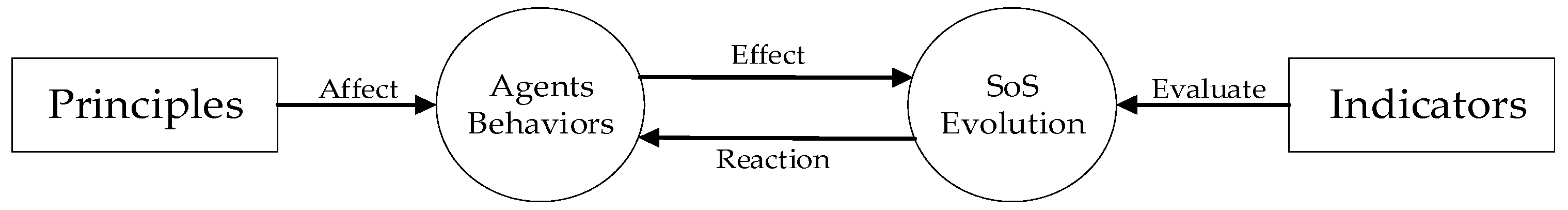

3.1. Overall Model Structure

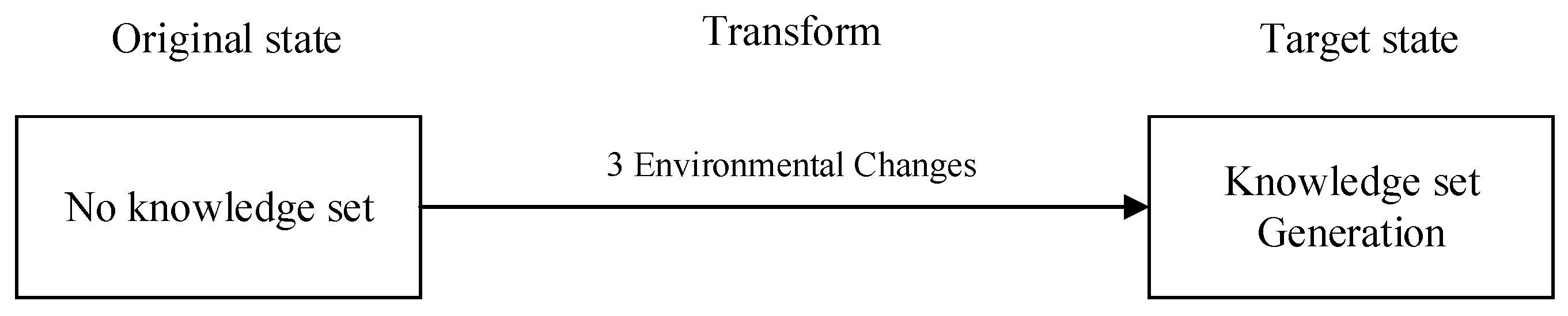

3.2. SoS Evolution

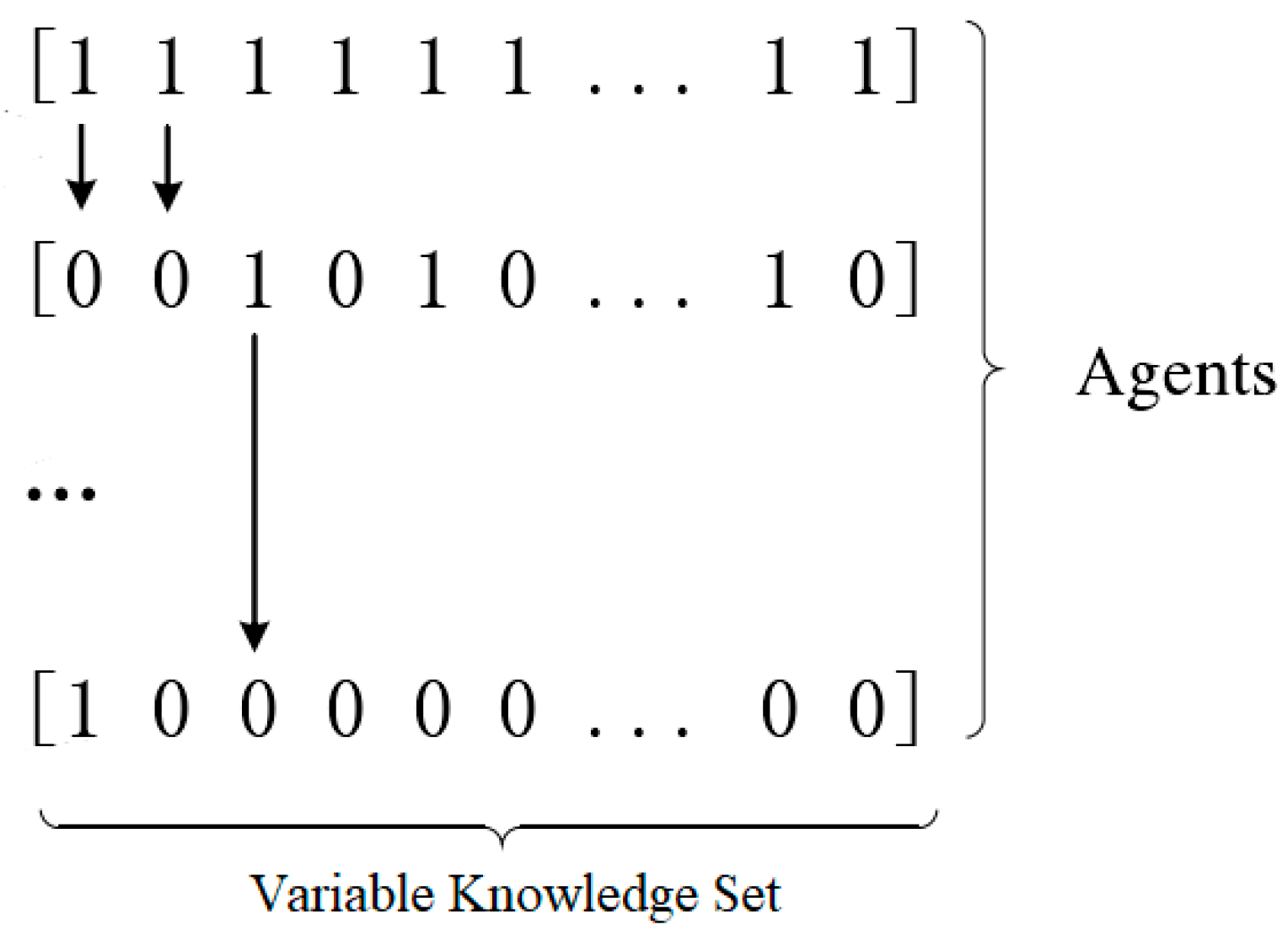

3.3. Agent Behaviors

3.4. Principle

3.5. Indicators

3.6. Monte Carlo Simulation and Model Verification

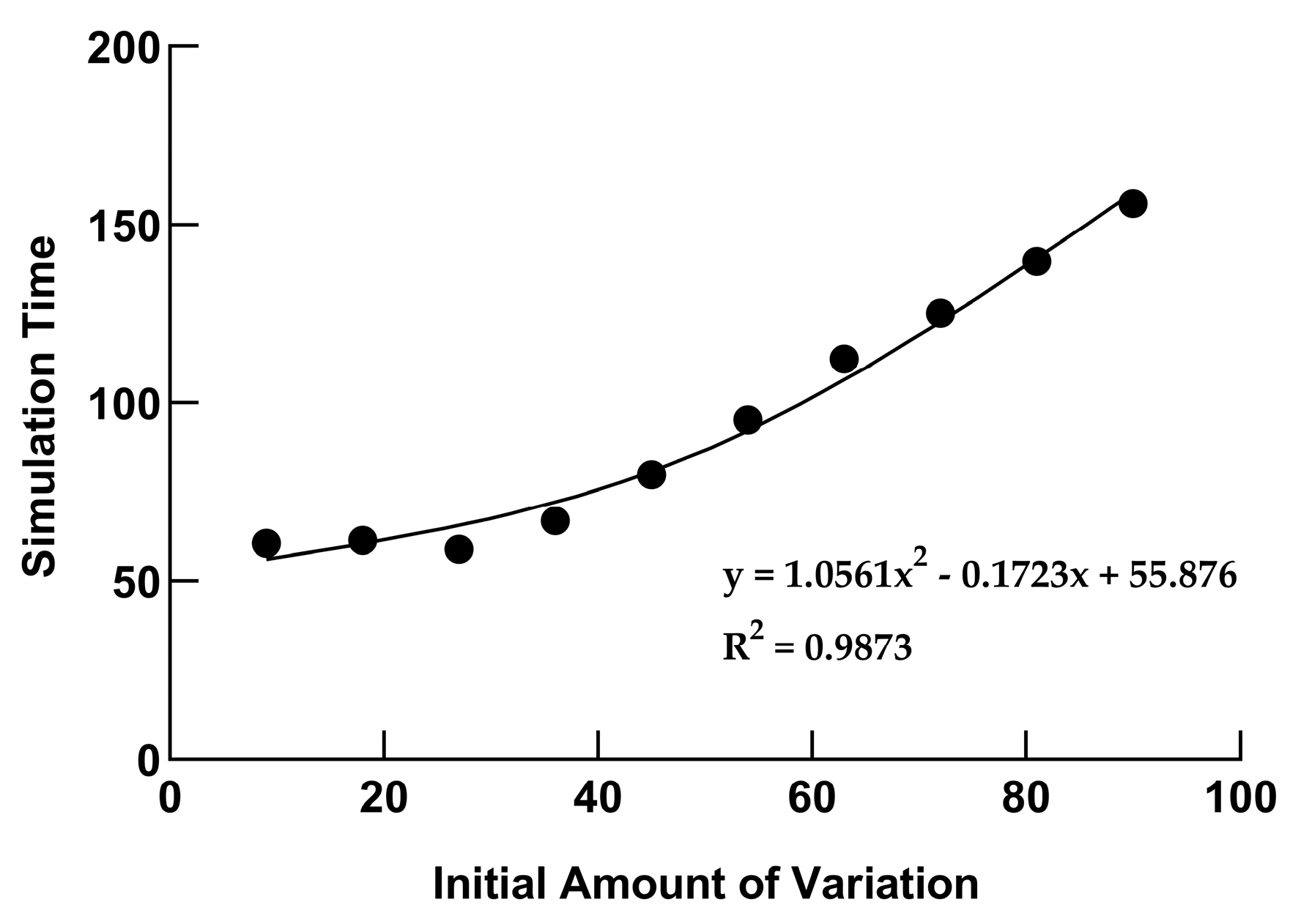

3.7. Time Complexity Analysis

4. Results

- (1)

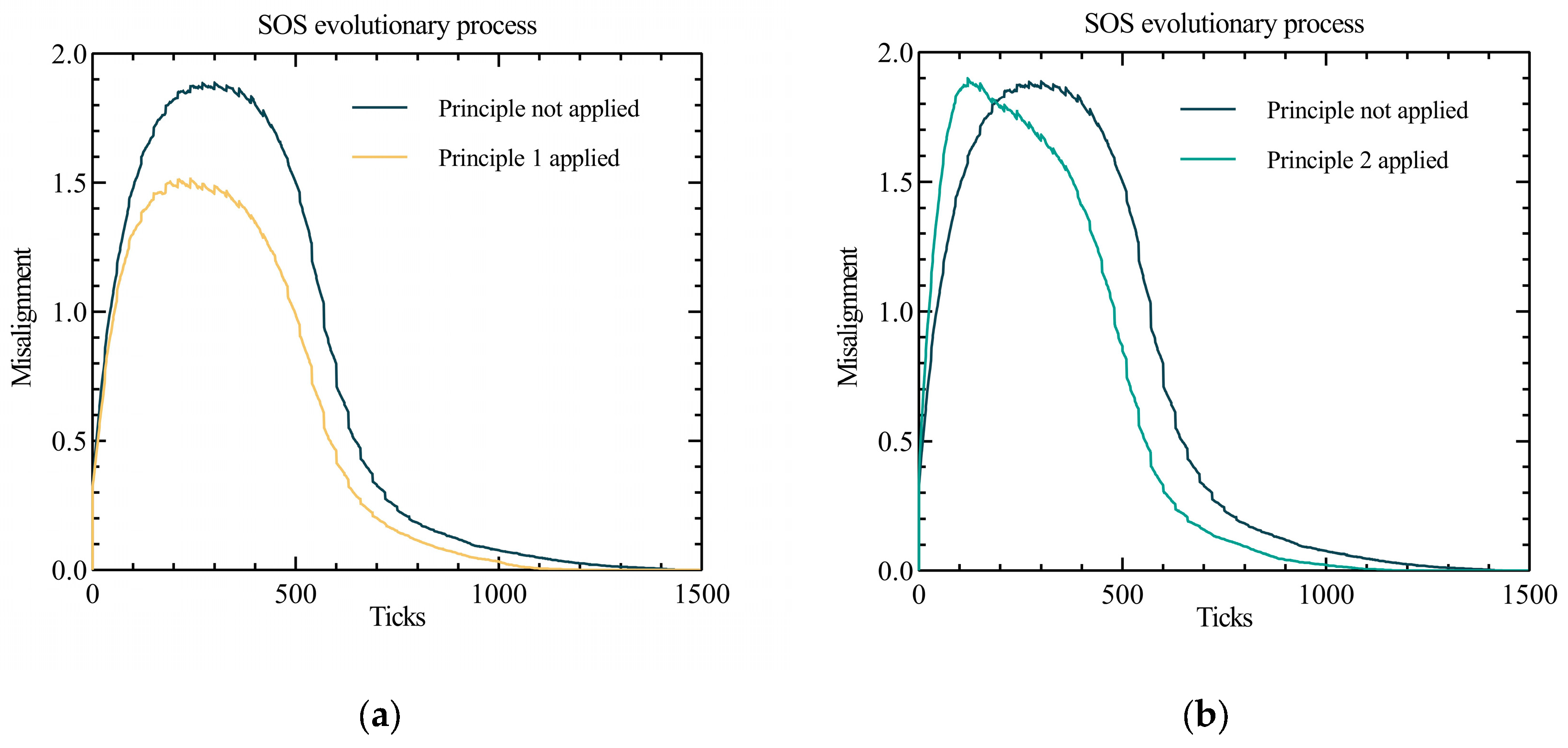

- The misalignment metrics in all four graphs showed an increasing and then decreasing trend. The reason for this phenomenon is that the initial interactions between some of the constituent systems increased the degree of difference between all nodes in the SoS under the influence of the external environment. As the interactions continued, evolution caused the degree of difference between most of the constituent systems to decrease, eventually leading to complete evolution.

- (2)

- The peak misalignment values in the plot for Principle 2 (Implementing Uniform Standards) occurred earlier than those without the application of the principle. The reason for this phenomenon is that the application of this principles increased the overall efficiency of the system at an early stage and different nodes in the installation received more new information in a short period of time, thus creating differences between the self-managed systems. Meanwhile, the peak misalignment values in the plot of principle 1 (Facilitating information exchange) was significantly lower than that without the application of the principle, probably as the exchange of information between nodes somewhat mitigated the degree of difference between the self-managed systems.

- (3)

- Compared to the control group, the misalignment values of the SoS with different principles applied were all improved, in terms of in the rate of decline after reaching the peak. As such, the time to complete SoS evolution was also shorter in all cases. This indicates that the application of different principles can enhance the efficiency of system evolution, to some extent.

- (1)

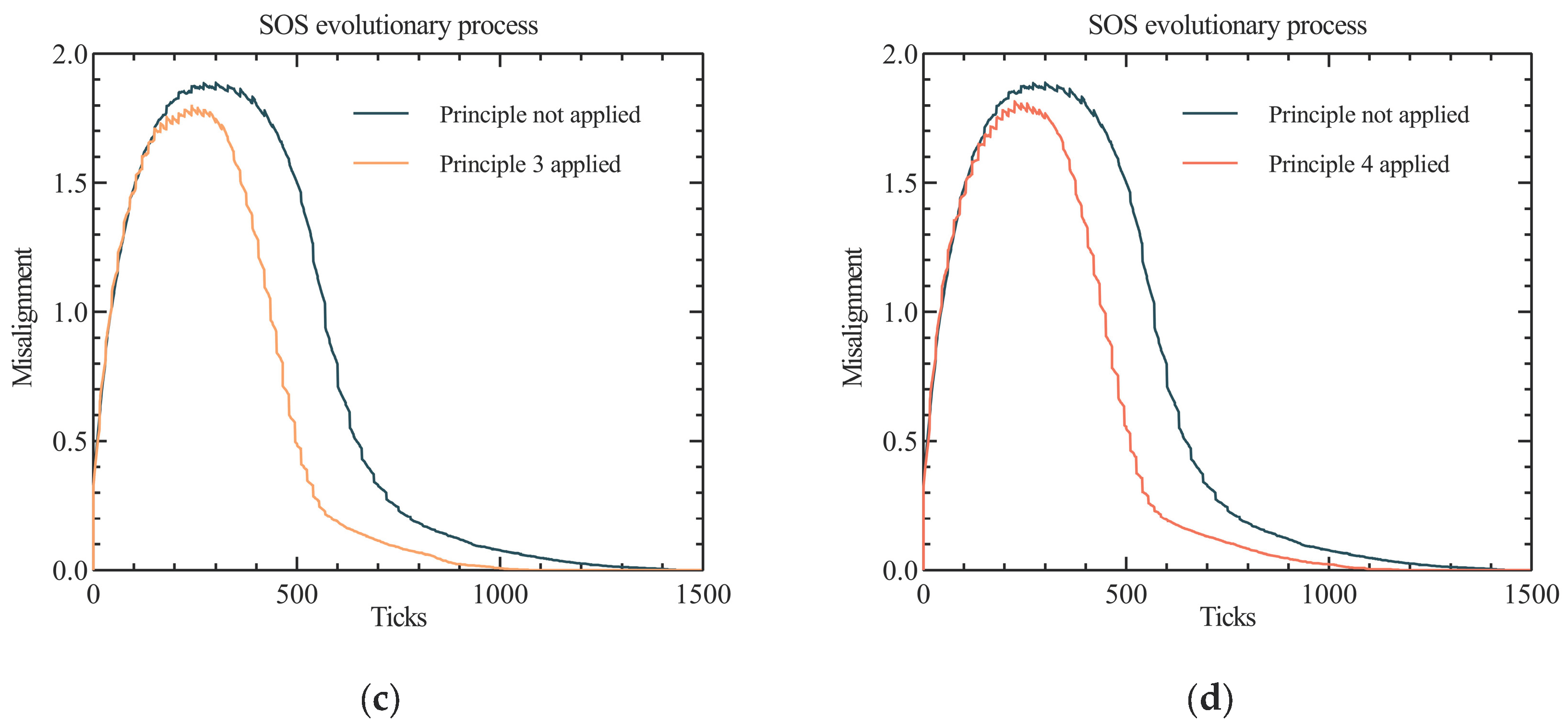

- Figure 6a shows the average evolution time of the SoS with the different principles applied. The evolution time for the SoS without applying any principles was 1181.2 s. The evolution times for the systems with Principle 1 and Principle 2 applied were close, at 989.8 s and 965.0 s, respectively (roughly 82% of the original time). Meanwhile, the average evolution time with Principle 4 applied was 954.8 s (80.8% of the original time), and the lowest evolution time was obtained with Principle 3, which was only 892.8 s (or 75.6% of the original time).

- (2)

- Figure 6b shows the degree of variation accumulated in the evolution of the SoS with the application of the different principles. All four principles reduced the degree of variation to a greater extent. The smallest reduction was obtained with Principle 2 (Implementing Uniform Standards), which was 83.8% of the baseline variance, while the greatest reduction in the degree of variation was achieved with Principle 1 (Facilitating information exchange), which was 72.3% of the baseline degree of variation.

5. Discussion

5.1. Elaboration of Experimental Outcomes

5.2. Evaluating the Efficacy and Limitations of the Model

5.3. Bridging Natural and Social Sciences: A Methodological Discourse

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameters | Values | Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Number of knowledge values contained in a single knowledge set | 30 60 90 |

Evolutionary time increases with the number of knowledge values and has little impact on the overall evolutionary trend. |

| Number of agents in the domain | 20 30 |

The evolution time increases with the number of agents, and the evolution trend is similar. |

| Number of groups of systems with connectivity in the domain | 1 2 4 |

The evolution time decreases with the increase in the number of groups, the evolution performance changes more drastically, and the evolution trend is roughly similar. |

| Number of goal-related changes | 0 2 3 |

Evolutionary time increases with the number of changes and has less impact on the overall evolutionary trend. |

| Number of standard-related changes | 0 2 3 |

Evolutionary time increases with the number of changes and has less impact on the overall evolutionary trend. |

| Number of task-related changes | 0 2 3 |

Evolutionary time increases with the number of changes and has less impact on the overall evolutionary trend. |

| Probability of information correspondence behavior within a group | 0.7 0.9 |

Evolutionary time decreases with increasing probability and has no effect on evolutionary trend. |

| Probability of data-sharing behavior within a group | 0.7 0.9 |

Evolutionary time decreases with increasing probability and has no effect on evolutionary trend. |

| Probability of consensus-seeking behavior within the group | 0.7 0.9 |

Evolutionary time decreases with increasing probability and has no effect on evolutionary trend. |

| Probability of information-correspondence behavior in the domain | 0.3 0.5 |

Evolutionary time decreases with increasing probability and has no effect on evolutionary trend. |

| Probability of data-sharing behavior in the domain | 0.3 0.5 |

Evolutionary time decreases with increasing probability and has no effect on evolutionary trend. |

| Probability of consensus-seeking behavior in the domain | 0.3 0.5 |

Evolutionary time decreases with increasing probability and has no effect on evolutionary trend. |

| Number of simulations per experimental condition | 20 40 |

No effect on evolutionary trends. |

References

- Selberg, S.A.; Austin, M.A. 10.1. 1 toward an evolutionary system-of-systems architecture. In Proceedings of the INCOSE International Symposium, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 15–19 June 2008; Volume 18, pp. 1065–1078. [CrossRef]

- Lock, R. Developing a methodology to support the evolution of system-of-systems using risk analysis. Syst. Eng. 2012, 15, 62–73. [CrossRef]

- Carney, D.; Fisher, D.; Place, P. Topics in Interoperability: System-of-Systems Evolution; Carnegie-Mellon Univ Pittsburgh Pa Software Engineering Inst: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2005.

- Lane, J.A.; Valerdi, R. Accelerating system-of-systems engineering understanding and optimization through lean enterprise principles. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Systems Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 5–8 April 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 196–201.

- Nielsen, C.B.; Larsen, P.G.; Fitzgerald, J.; Woodcock, J.; Peleska, J. Systems of systems engineering: Basic concepts, model-based techniques, and research directions. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2015, 48, 1–41.

- Hildebrandt, N.; Spillmann, C.M.; Algar, W.R.; Pons, T.; Stewart, M.H.; Oh, E.; Susumu, K.; Díaz, S.A.; Delehanty, J.B.; Medintz, I.L. Energy transfer with semiconductor quantum dot bioconjugates: A versatile platform for biosensing, energy harvesting, and other developing applications. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 536–711. [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.A.; Beare, D.; Boutselakis, H.; Bamford, S.; Bindal, N.; Tate, J.; Cole, C.G.; Ward, S.; Dawson, E.; Ponting, L.; et al. COSMIC: Somatic cancer genetics at high-resolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D777–D783. [CrossRef]

- Ott, P.A.; Hu, Z.; Keskin, D.B.; Shukla, S.A.; Sun, J.; Bozym, D.J.; Zhang, W.; Luoma, A.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Peter, L.; et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature, 2017, 547, 217–221. [CrossRef]

- Maier, M.W. Architecting principles for systems-of-systems. In Proceedings of the INCOSE 1996 6th Annual International Symposium of the International Council on Systems Engineering, 7–11 July 1996; INCOSE: Boston, MA, USA.

- Abbott, R. Open at the top; open at the bottom; and continually (but slowly) evolving. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE/SMC International Conference on system-of-systems Engineering, Los Angeles, CA, USA 26–28 April 2006; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; p. 6.

- Bloomfield, R.; Gashi, I. Evaluating the Resilience and Security of Boundaryless, Evolving Socio-Technical Systems of Systems; Technical Report; Centre for Software Reliability, City University: London, UK, 2008.

- Carlock, P.G.; Fenton, R.E. system-of-systems (SoS) enterprise systems engineering for information-intensive organizations. Syst. Eng. 2001, 4, 242–261.

- Crossley, W.A. system-of-systems: An introduction of Purdue University schools of Engineering’s Signature Area. In Engineering Systems Symposium; MIT Engineering Systems Division: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004.

- Despotou, G.; Alexander, R.; Hall-May, M. Key Concepts and Characteristics of Systems of Systems (SoS); DARP-HIRTS; University of York: York, UK, 2003.

- Smith, D.; Lewis, G. Systems of Systems: New challenges for maintenance and evolution. In Proceedings of the 2008 Frontiers of Software Maintenance, Beijing, China, 28 September–4 October 2008; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008: 149-157.

- Clausing, D.P.; Andrade, R. Strategic reusability. In Proceedings of the Engineering Design Conference'98,: Design Reuse, London, UK, 23–25 June 1998; pp. 98–101.

- Vargas, I.G.; Gottardi, T.; Braga, R.T.V. Approaches for integration in system-of-systems: A systematic review[C]//2016 IEEE/ACM 4th International Workshop on Software Engineering for Systems-of-Systems (SESoS), Austin, TX, USA, 16 May 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 32–38.

- Chen, P.; Han, J. Facilitating system-of-systems evolution with architecture support. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Principles of Software Evolution, Vienna, Austria, 10–11 September 2001; pp. 130–133.

- Ackoff, R.L. Towards a system-of-systems concepts. Manag. Sci. 1971, 17, 661–671. [CrossRef]

- Clausing, D. Reusability in Product Development, In Proceedings of the Engineering Design Conference'98,: Design Reuse, London, UK, 23–25 June 1998; pp. 57–66.

- Sahin, F.; Jamshidi, M.; Sridhar, P. A discrete event xml based simulation framework for system-of-systems architectures. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on system-of-systems Engineering, San Antonio, TX, USA, 16–18 September 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 1–7.

- Kazman R, Schmid K, Nielsen C B; et al. Understanding patterns for system-of-systems integration. In Proceedings of the 2013 8th International Conference on system-of-systems Engineering, Maui, HI, USA, 2–6 June 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013: 141-146.

- Baker, J.; Singh, H. The roots of misalignment: Insights from a system dynamics perspective. In Proceedings of the JAIS Theory Development Workshop, Fort Worth, TX, USA, 13 December 2015; pp. 1–37.

- Benbya, H.; McKelvey, B. Using coevolutionary and complexity theories to improve IS alignment: A multi-level approach. J. Inf. Technol. 2006, 21, 284–298. [CrossRef]

- Tanriverdi, H.; Lim, S.Y. How to survive and thrive in complex, hypercompetitive, and disruptive ecosystems? The roles of IS-enabled capabilities. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Information Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 10–13 December 2017; pp. 1–21.

- Besson, P.; Rowe, F. Strategizing information systems-enabled organizational transformation: A transdisciplinary review and new directions. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2012, 21, 103–124. [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The framing decisions and the psychology of choice. In Question Framing and Response Consistency; Hogarth, R., Ed.; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1982.

- Daft, R.L.; Wiginton, J.C. Language and organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 179–191.

- Lind, J. Specifying agent interaction protocols with standard UML. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Agent-Oriented Software Engineering, Montreal, QC, Canada, 29 May 2001; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 136–147.

- Schnackenberg A K, Tomlinson E C. Organizational transparency: A new perspective on managing trust in organization-stakeholder relationships[J]. Journal of management, 2016, 42(7): 1784-1810.

- Akkermans, H.; Bogerd, P.; Van Doremalen, J. Travail, transparency and trust: A case study of computer-supported collaborative supply chain planning in high-tech electronics. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 153, 445–456. [CrossRef]

- Foa, U.G.; Foa, E.B.; Schwarz, L.M. Nonverbal communication: Toward syntax, by way of semantics. J. Nonverbal Behav. 1981, 6, 67–83. [CrossRef]

- Calvaresi, D.; Najjar, A.; Winikoff, M.; Främling, K. Explainable, Transparent Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems; Second International Workshop, EXTRAAMAS 2020, Auckland, New Zealand, May 9–13, 2020, Revised Selected Papers; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020.

- González A, Piel E, Gross H G; et al. Testing challenges of maritime safety and security systems-of-systems. In Proceedings of the Testing: Academic & Industrial Conference-Practice and Research Techniques (Taic Part 2008), Windsor, ON, USA, 29–31 August 2008; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 35–39.

- Cvitanovic, C.; Colvin, R. M.; Reynolds, K. J.; Platow, M. J. Applying an organizational psychology model for developing shared goals in interdisciplinary research teams. One Earth. 2020, 2, 75–83. [CrossRef]

- Ohnuma, S. Consensus building: Process design toward finding a shared recognition of common goal beyond conflicts. In Handbook of Systems Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 645–662.

- de Amorim Silva, R.; Braga, R.T.V. Simulating systems-of-systems with agent-based modeling: A systematic literature review. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 14, 3609–3617. [CrossRef]

- Kinder, A.; Henshaw, M.; Siemieniuch, C. system-of-systems modelling and simulatio—An outlook and open issues. Int. J. Syst. Syst. Eng. 2014, 5, 150–192.

- AMour, A.; Kenley, C.R.; Davendralingam, N.; DeLaurentis, D. Agentbased modeling for systems of systems. In 23nd Annual International Symposium of the International Council of Systems Engineering, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 24–27 June 2013; Volume 1, pp. 250–264.

- Tivnan, B.F. Coevolutionary dynamics and agent-based models in organization science. In Proceedings of the 37th Conference on Winter Simulation Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 4–7 December 2005; pp. 1013–1021.

- Wooldridge, M.; Jennings, N.R. Intelligent agents: theory and practice. The knowledge engineering review. 1995, 10, 115–152. [CrossRef]

- Macal, C. M.; NORTH, M. J. Tutorial on agent-based modelling and simulation. Journal of Simulation. 2010, 4, 151-162. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S. The Origins of Order: Selforganization and Selection in Evolution; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993.

- Nagel, K.; Schreckenberg, M. A cellular automaton model for freeway traffic. Journal de Physique. 1992, 2, 2221-2229. [CrossRef]

- Nagel, K.; Flötteröd, G. Agent-based traffic assignment: going from trips to behavioral travelers. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Travel Behaviour Research IATBR, Jaipur, India, 14-18 November 2009; pp. 261-294.

- Zhu, S; Levinson, D. Do people use the shortest path? An empirical test of Wardrop’s first principle. PloS one, 2015, 10, e0134322. [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Levinson, D. A Multi-Agent Congestion and Pricing Model. Transportmetrica. 2006, 2, 237-249. [CrossRef]

- Levy, N.; Martens, K.; Benenson, I. Exploring cruising using agent-based and analytical models of parking. Transportmetrica A: Transport Science. 2013, 9, 773-797. [CrossRef]

- Bosse S. Self-organising Urban Traffic control on micro-level using Reinforcement Learning and Agent-based Modelling[C]//Intelligent Systems and Applications: Proceedings of the 2020 Intelligent Systems Conference (IntelliSys) Volume 2. Springer International Publishing, 2021: 745-764.

- Bui K H N, Camacho D, Jung J E. Real-time traffic flow management based on inter-object communication: a case study at intersection[J]. Mobile Networks and Applications, 2017, 22: 613-624.

- Wang J, Lv W, Jiang Y, et al. A multi-agent based cellular automata model for intersection traffic control simulation[J]. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 2021, 584: 126356.

- Shang W, Han K, Ochieng W, et al. Agent-based day-to-day traffic network model with information percolation[J]. Transportmetrica A: Transport Science, 2017, 13(1): 38-66.

- Mahdi M A, Hasson S T. Complex agent network approach to model mobility and connectivity in vehicular social networks[J]. J. Eng. Appl. Sci, 2018, 13: 2288-2295.

- Zia K, Shafi M, Farooq U. Improving recommendation accuracy using social network of owners in social internet of vehicles[J]. Future Internet, 2020, 12(4): 69.

- Rathee G, Garg S, Kaddoum G, et al. Trusted computation using ABM and PBM decision models for its[J]. IEEE Access, 2020, 8: 195788-195798.

- Peppard, J.; Breu, K. Beyond alignment: A coevolutionary view of the information systems strategy process. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Information Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 15–17 December 2003; pp. 61–69.

- Baldwin, W.C.; Ben-Zvi, T.; Sauser, B.J. Formation of collaborative system-of-systems through belonging choice mechanisms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Part A Syst. Hum. 2011, 42, 793–801. [CrossRef]

- Sindiy, O.V.; DeLaurentis, D.A.; Stein, W.B. An agent-based dynamic model for analysis of distributed space exploration architectures. J. Astronaut. Sci. 2009, 57, 579–606. [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, I.; Dijkema, G.P.J. Framework for Understanding and Shaping Systems of Systems The case of industry and infrastructure development in seaport regions. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on system-of-systems Engineering, San Antonio, TX, USA, 16–18 September 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 1–6.

- Grimm, V.; Railsback, S.F.; Vincenot, C.E.; Berger, U.; Gallagher, C.; DeAngelis, D.L.; Edmonds, B.; Ge, J.; Giske, J.; Groeneveld, J.; et al. The ODD Protocol for Describing Agent-Based and Other Simulation Models: A Second Update to Improve Clarity, Replication, and Structural Realism. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2020, 23, 7. [CrossRef]

- Alkire, A.A.; Collum, M.E.; Kaswan, J. Information exchange and accuracy of verbal communication under social power conditions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 9, 301. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.L. Information exchange in negotiation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 27, 161–179. [CrossRef]

- Maginnis, M.A. The impact of standardization and systematic problem solving on team member learning and its implications for developing sustainable continuous improvement capabilities. J. Enterp. Transform. 2013, 3, 187–210. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, G.W.; Rutherford, T.F.; Tarr, D.G. Increased competition and completion of the market in the European Union: Static and steady state effects. J. Econ. Integr. 1996, 11, 332–365.

- Tassey, G. Standardization in technology-based markets. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 587–602. [CrossRef]

- Albu, O.B.; Flyverbom, M. Organizational transparency: Conceptualizations, conditions, and consequences. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 268–297. [CrossRef]

- Michener, G. Gauging the impact of transparency policies. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 136–139. [CrossRef]

- Noveck, B.S. Rights-based and tech-driven: Open data, freedom of information, and the future of government transparency. Yale Hum. Rights Dev. Law J. 2017, 19, 1–45.

- Kolleck, N.; Rieck, A.; Yemini, M. Goals aligned: Predictors of common goal identification in educational cross-sectoral collaboration initiatives. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 48, 916–934.

- Thayer-Bacon, B.J.; Brown, S. What “Collaboration” Means: Ethnocultural Diversity’s Impact. United States Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement.: Washington, DC, 1995.

- Weingart, L.R.; Bennett, R.J.; Brett, J.M. The impact of consideration of issues and motivational orientation on group negotiation process and outcome. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 504.

- Shendell-Falik, N. The art of negotiation. Prof. Case Manag. 2002, 7, 228–230.

- Lee, J.-S.; Filatova, T.; Ligmann-Zielinska, A.; Hassani-Mahmooei, B.; Stonedahl, F.; Lorscheid, I.; Voinov, A.; Polhill, G.; Sun, Z.; Parker, D.C. The complexities of agent-based modeling output analysis. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2015, 18. [CrossRef]

- Bruch, E.; Atwell, J. Agent-based models in empirical social research. Sociol. Methods Res. 2015, 44, 186–221. [CrossRef]

- Meluso, J.; Austin-Breneman, J. Gaming the system: An agent-based model of estimation strategies and their effects on system performance. J. Mech. Des. 2018, 140, 121101. [CrossRef]

- Sarjoughian, H.S.; Zeigler, B.P.; Hall, S.B. A layered modeling and simulation architecture for agent-based system development. Proc. IEEE 2001, 89, 201–213. [CrossRef]

- Crowder, R.M.; Robinson, M.A.; Hughes, H.P.N.; Sim, Y.-W. The development of an agent-based modeling framework for simulating engineering team work. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Part A Syst. Hum. 2012, 42, 1425–1439. [CrossRef]

- Fioretti, G. Agent-based simulation models in organization science. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 227–242. [CrossRef]

- Jović M, Tijan E, Žgaljić D, et al. Improving maritime transport sustainability using blockchain-based information exchange[J]. Sustainability, 2020, 12(21): 8866.

- Deng S, Zhou D, Wu G, et al. Evolutionary game analysis of three parties in logistics platforms and freight transportation companies’ behavioral strategies for horizontal collaboration considering vehicle capacity utilization[J]. Complex & Intelligent Systems, 2023, 9(2): 1617-1637.

- Love T E, Ehrenberg N, Sapere Research Group. Addressing unwarranted variation: literature review on methods for influencing practice[M]. New Zealand: Health Quality & Safety Commission, 2014.

- Hinds P J, Mortensen M. Understanding conflict in geographically distributed teams: The moderating effects of shared identity, shared context, and spontaneous communication[J]. Organization science, 2005, 16(3): 290-307. [CrossRef]

- Ray K. One size fits all? Costs and benefits of uniform accounting standards[J]. Journal of International Accounting Research, 2018, 17(1): 1-23.

- Latin H. Ideal versus real regulatory efficiency: Implementation of uniform standards and fine-tuning regulatory reforms[J]. Stan. L. Rev., 1984, 37: 1267.

- Elmer C F. The Economics of Vehicle CO 2 Emissions Standards and Fuel Economy Regulations: Rationale, Design, and the Electrification Challenge[M]. Technische Universitaet Berlin (Germany), 2016.

- Foscht T, Lin Y, Eisingerich A B. Blinds up or down? The influence of transparency, future orientation, and CSR on sustainable and responsible behavior[J]. European Journal of Marketing, 2018, 52(3/4): 476-498.

- Kumar N, Ganguly K K. External diffusion of B2B e-procurement and firm financial performance: Role of information transparency and supply chain coordination[J]. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 2021, 34(4): 1037-1060.

- Cheng M, Liu G, Xu Y, et al. Enhancing trust between PPP partners: The role of contractual functions and information transparency[J]. Sage Open, 2021, 11(3): 21582440211038245.

- Lee U K. The effect of information deception in price comparison site on the consumer reactions: an empirical verification[J]. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, 2015, 11(9): 270685.

- Che T, Wu Z, Wang Y, et al. Impacts of knowledge sourcing on employee innovation: the moderating effect of information transparency[J]. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2019, 23(2): 221-239.

- Wu Y, Zhang K, Xie J. Bad greenwashing, good greenwashing: Corporate social responsibility and information transparency[J]. Management Science, 2020, 66(7): 3095-3112.

- Chen Y H, Lin T P, Yen D C. How to facilitate inter-organizational knowledge sharing: The impact of trust[J]. Information & management, 2014, 51(5): 568-578.

- Verberne F M F, Ham J, Midden C J H. Trust in smart systems: Sharing driving goals and giving information to increase trustworthiness and acceptability of smart systems in cars[J]. Human factors, 2012, 54(5): 799-810.

- Li J J, Poppo L, Zhou K Z. Relational mechanisms, formal contracts, and local knowledge acquisition by international subsidiaries[J]. Strategic Management Journal, 2010, 31(4): 349-370.

- Wang L, Song M, Zhang M, et al. How does contract completeness affect tacit knowledge acquisition?[J]. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2021, 25(5): 989-1005.

- Wang N, Huang Y, Fu Y, et al. Does lead userness matter for electric vehicle adoption? An integrated perspective of social capital and domain-specific innovativeness[J]. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 2022, 21(6): 1405-1419.

- Hayek F A. The counter-revolution of science[J]. Economica, 1941, 8(31): 281-320.

- Popper K. The logic of scientific discovery[M]. Routledge, 2005.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).