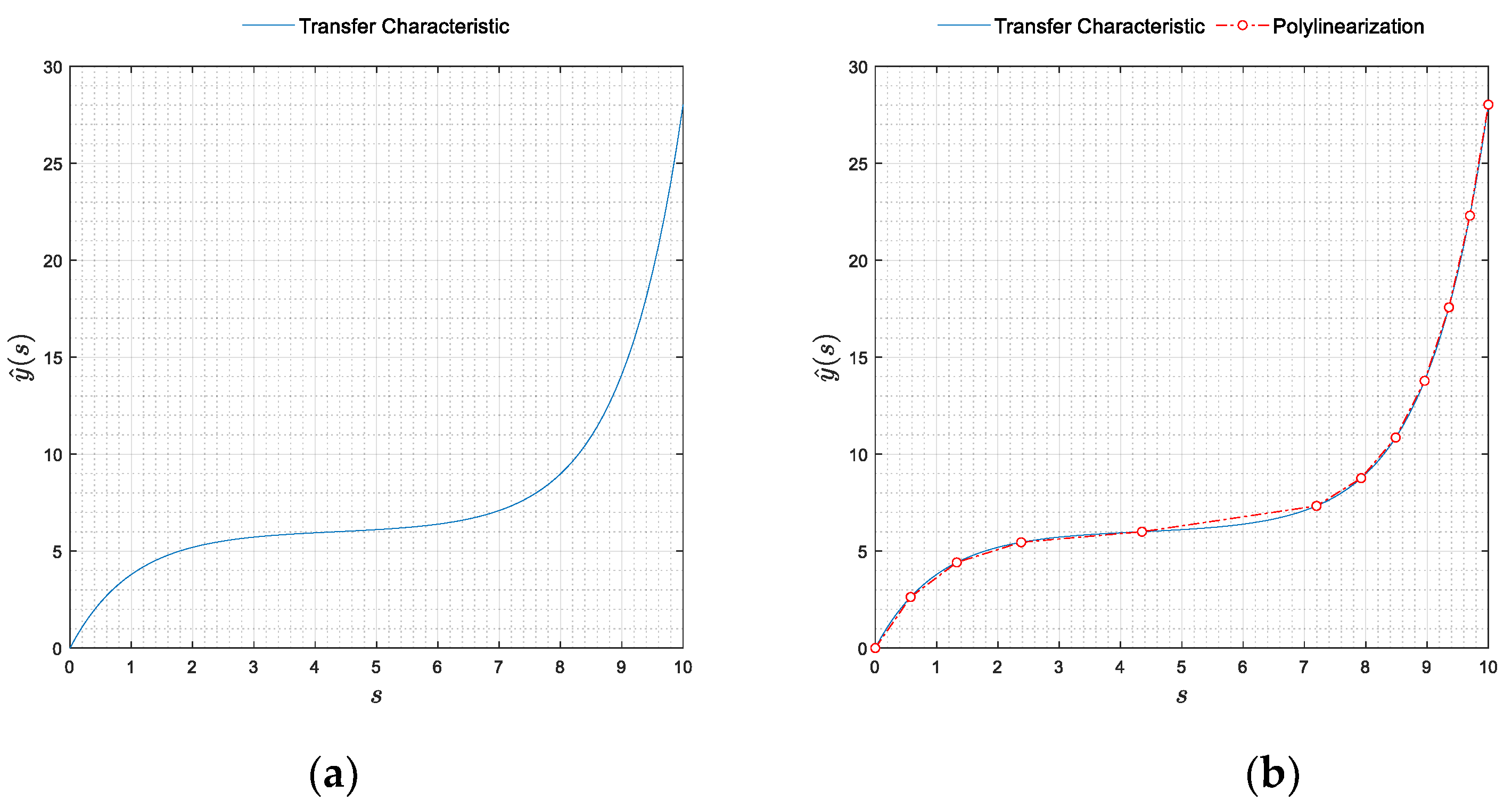

The approximation of given sensor transfer functions by polylines called in the following polylinearization, rests upon three central concepts: the curve segment, the (poly)line segment, and the measure of the remoteness between them. While the curve segment is a differential geometric concept, the polyline segment arises from a much more mundane issue: the need to approximate “in the best possible way” the curve segment by a compact straight line. Conceptually the process of polylinearization of a given sensor characteristic consists of three algebraic stages. The first (not a subject of the present work) is the representation of the sensor transfer function, i.e. the derivation of its algebraic equations from the physical principles. The second stage is the quantification of the remoteness between the curve and each of its approximating polyline segments. Finally, the third, and in many ways the most important one, is how to construct the polyline best fitting the entire curve, based on the measurement of the remoteness between the curve and the line segments building that polyline.

In this context, this section is an introduction to the instrumentation we will use later on with the following key notions and procedures covered:

2.1. Linearization and Polylinearization Costs

The position (point) in space is indicated by bold lowercase italic letters, such as , etc.

Let's start with the concepts of curve and curve segment: also, given the subset and the natural number, . For , we call the vector-valued map,

a parametrized curve immersed in

and write

for the points

on the curve. A curve,

is called simple if it does not intersect itself, and rectifiable if it has a finite length. Furthermore, if

is rectifiable then it is at least of class

and hence regular. In the following, we deal with simple, rectifiable curves. Set next

and focus on a particular segment

with

. The image,

is called the curve segment, starting at

and ending at

. Let’s clarify next what we mean by a line segment, attached to a curve segment

. For this purpose, we introduce the affine map,

with domain

and image

. Clearly at

,

, and at

we have

.

The line segment,

, attached to

at

and

is defined by,

where

How close are

and

to each other on

? To estimate their proximity we introduce the measure,

and refer to it as the linearization cost on

. In this expression, the

-norm, of the difference,

is,

with

, for

.

The notion of linearization cost - essentially localized in

- allows easy extension to the entire domain

. Accordingly, let

be an ascendant partition of

, furnished by the nodes

, and such that

for

. We call mesh the union,

of subdomains,

, i.e. the union of bounded, closed sets, with nonempty interior. Extending, the concept of linearization cost from a single line to a polyline we introduce the

-norm,

on

, which shall be referred to in the following as the polylinearization cost. Here,

In other words, is the polyline on , consisting of an open chain of line segments, , with the end of each previous segment serving as the beginning of the next.

Consider further the question of the existence of an optimal polylinearization. Focus first on the case of fixed

(and hence

). To answer that question, beginning from the observation,

and notice, that

with

called the characteristic size of the mesh. On another side, the inequality

implies the estimate

Hence, the area error is constrained to lie between the following two bounds:

,

expressed in terms of the polylinearization cost the fixed number of line segments and the characteristic mesh size . Since the curve is simple and rectifiable, this inequality expresses mathematically the two conditions for the existence of an optimal polylinearization, viz:

- a)

For a fixed domain there exists such that and the total area error attain their minima.

- b)

For a fixed domain there exists such that and the total area error attain their minima.

Regarding a), indeed, an increase of decreases and which in turn, due to the above inequality, implies a decrease in the total area error Analogously, for b), a decrease of increases and decreases which in turn implies a decrease in the total area error

Therefore, among all admissible nodal locations

, and their associated meshes

there exists at least one, which we designate by

, which minimizes the polylinearization cost

and consequently reduces the total area error. Designate next, the mesh associated with this partitioning by

, and notice that if

minimizes

it will be also the minimizer of the squared polylinearization cost

which constitutes a quadratic objective function in the nonlinear problem for optimal polylinearization of rectifiable, planar curves, formulated in the next section. Furthermore, for the range of the total area error we now have the estimate

Alternatively, let

and

be the partition and the associated mesh minimizing the total squared area error

In general,

, and hence

. Furthermore, for the range of the associated polylinearization cost we analogously have the estimate,

In other words, whichever error we choose to minimize, the other one will be minimized too.

2.2. Remoteness Measures

If is fixed, we will not get controllably close to the polyline by node reallocation alone, as we also need a mechanism to introduce ("inject") more nodes where it is most necessary. For that to happen, we need one more concept, or more precisely, an -dependent, generalized measure of distance, which we call remoteness measure. Why introduce yet another measure? The reason is primarily epistemological. The optimal polylinearization of a curve consists of two sub-problems: the first is related to "injecting" nodes where they are needed, and the second is related to reallocating these nodes to the positions where they are needed. The latter of these problems has already been addressed. Below we discuss the former.

Intuitively, an object is as close to another object as its farthest parts are. When the objects are a curve and a polyline, it is natural to ask whether there is a way to estimate how close the farthest segments of the curve and polyline are to each other. The answer to this question is affirmative, and below we present (with its purpose and merits) a quantitative measure of the distance between a curve and a polyline based on the largest distance between their building components. As it will become also clear, the remoteness is an upper bound on , and depends on the number of nodes, . The latter is crucial as it provides us with the tool to directly influence by modifying its upper bound, or equivalently, by modifying . Furthermore, since the remoteness operates on the line segments furthest from the curve, it will also serve as an identifier of these in which it is feasible to "inject" more nodes.

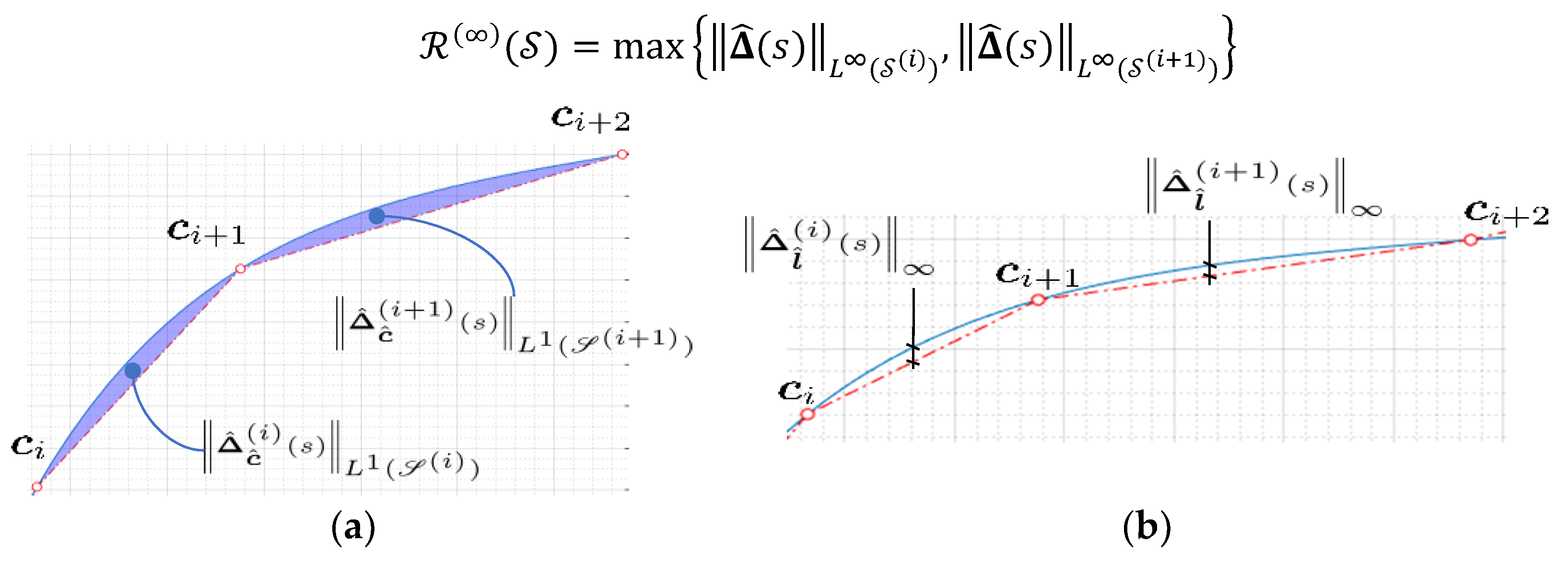

Under remoteness measure of order

, associated with the mesh

, we will understand the limit

and shall be interested in calculating it for two particular choices of

, corresponding to:

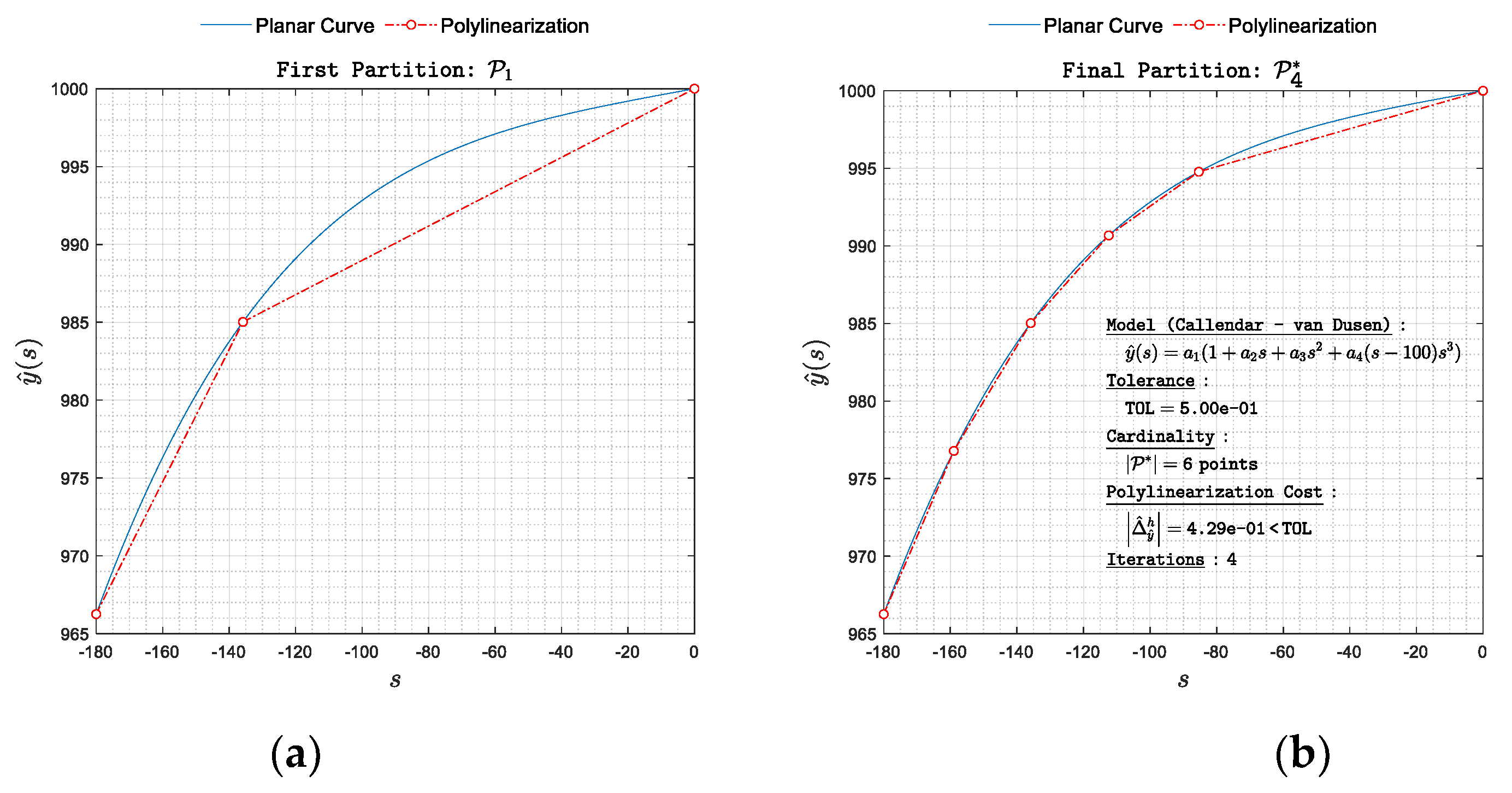

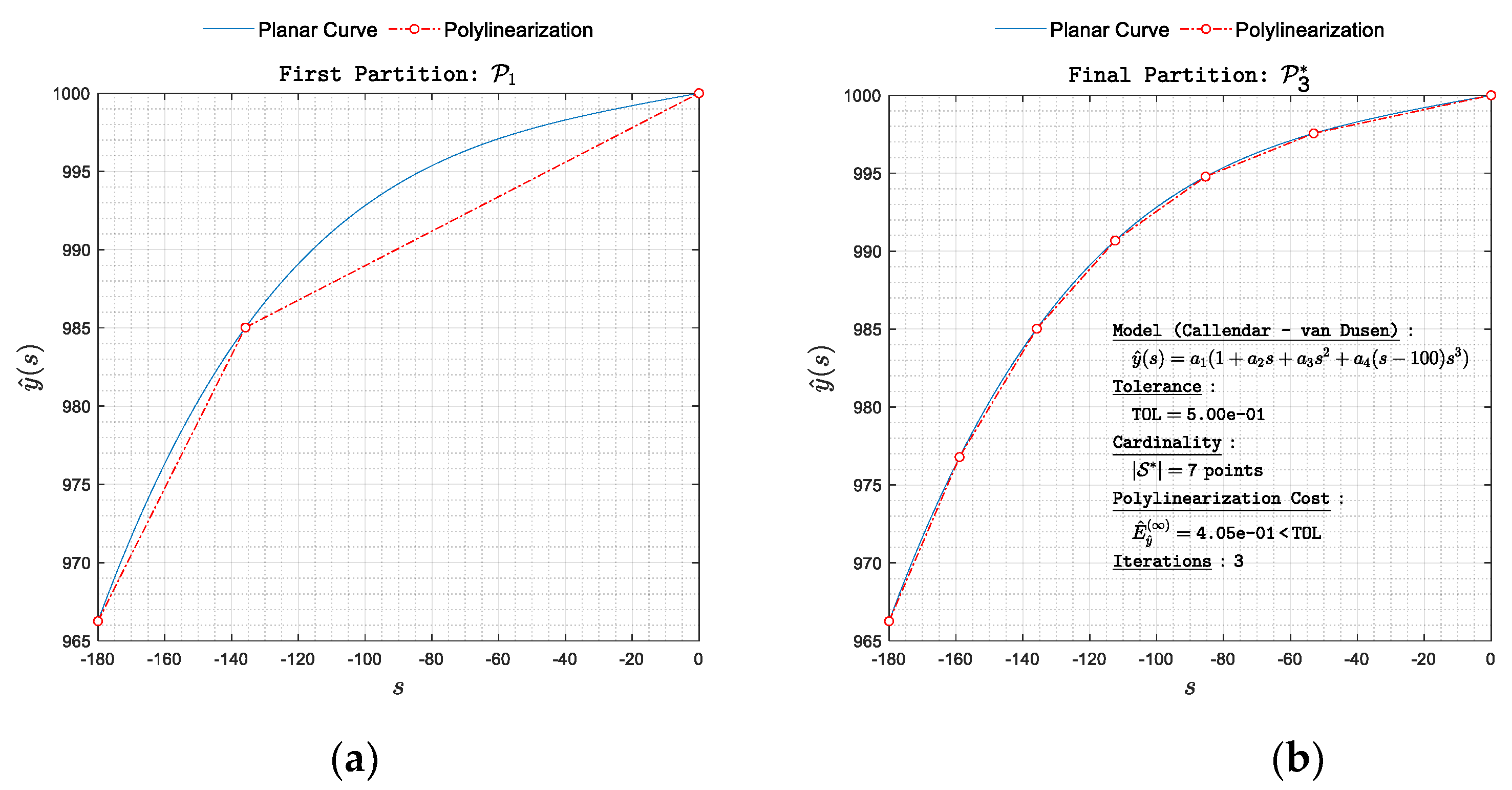

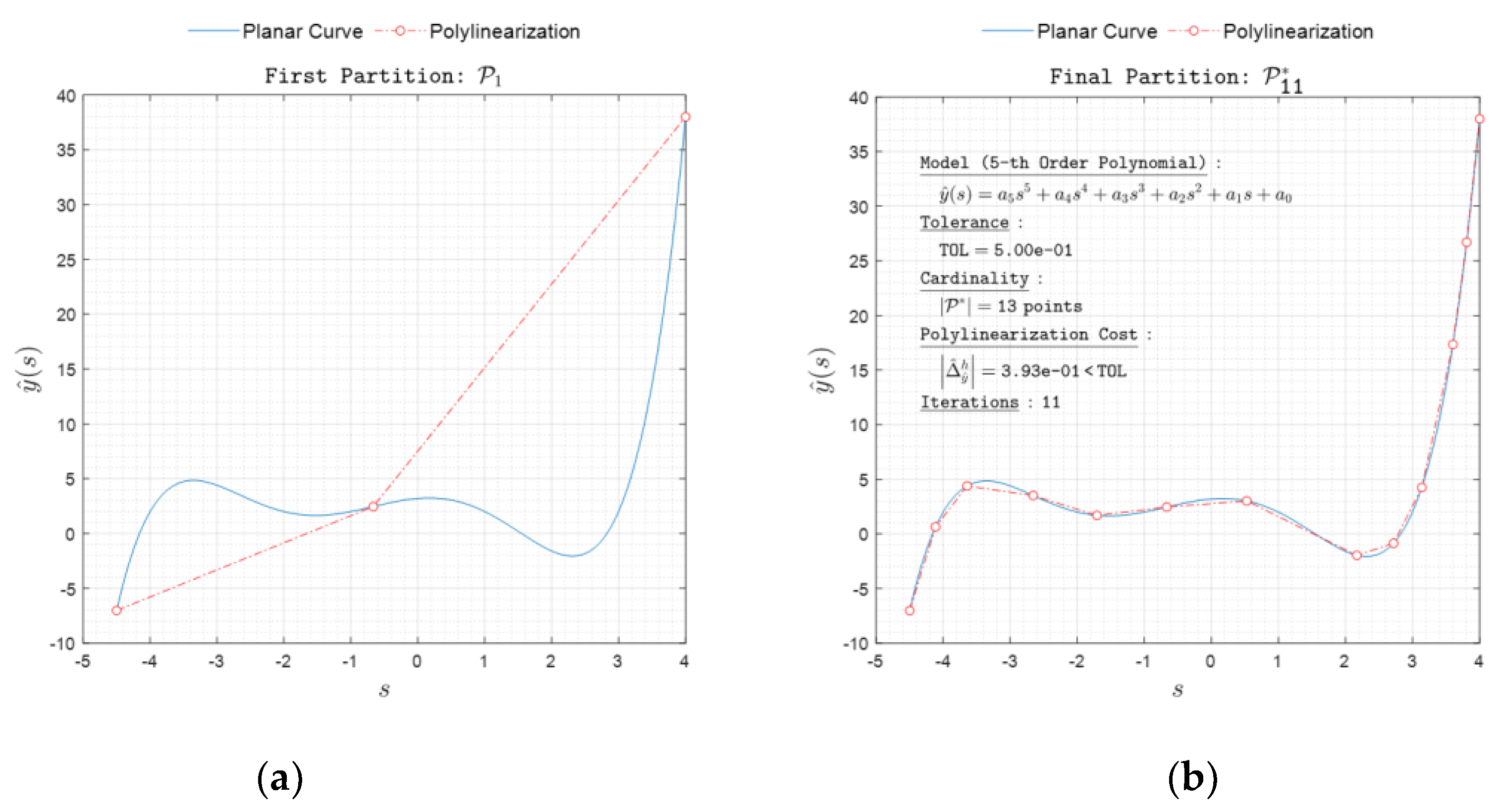

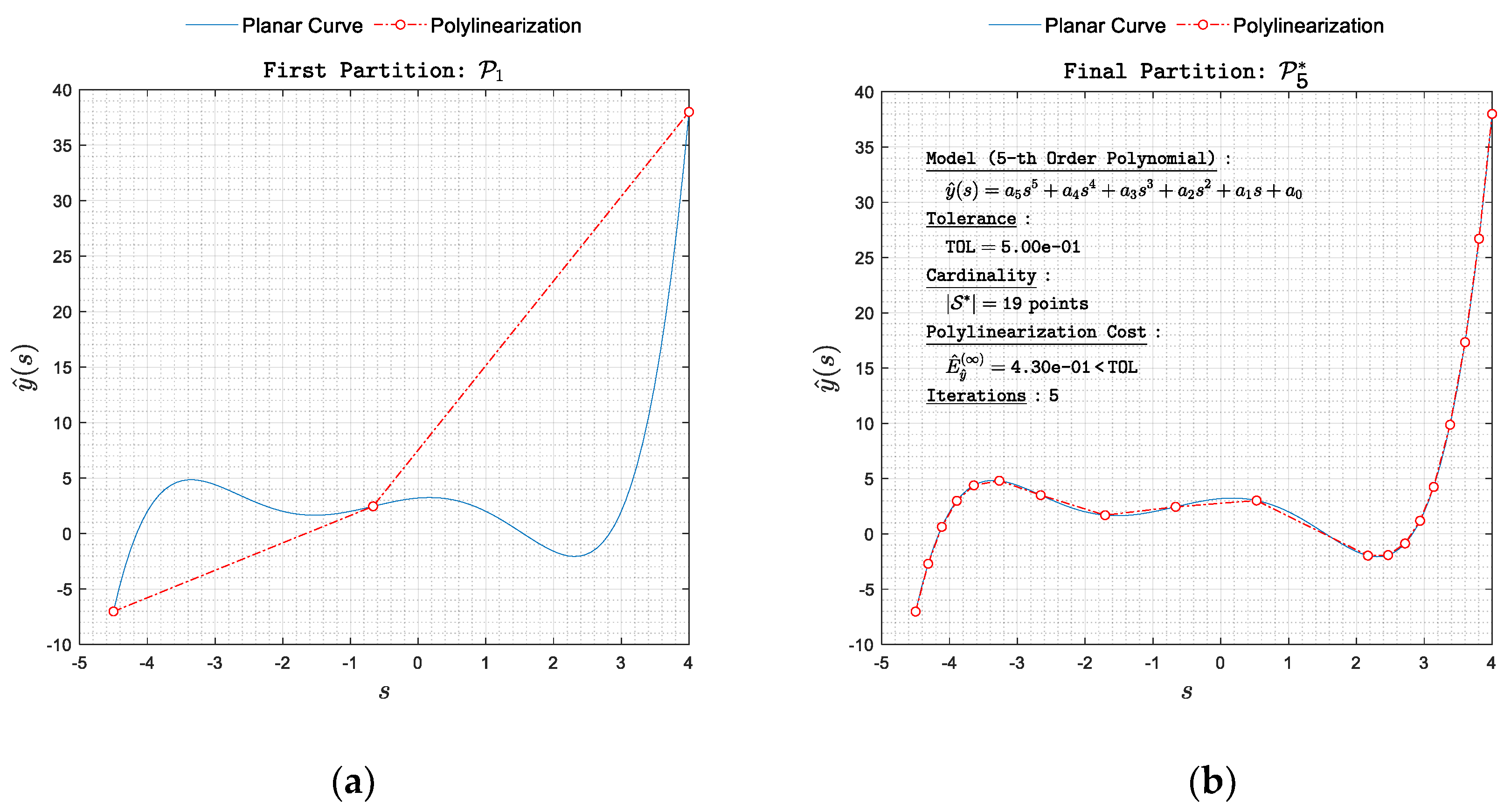

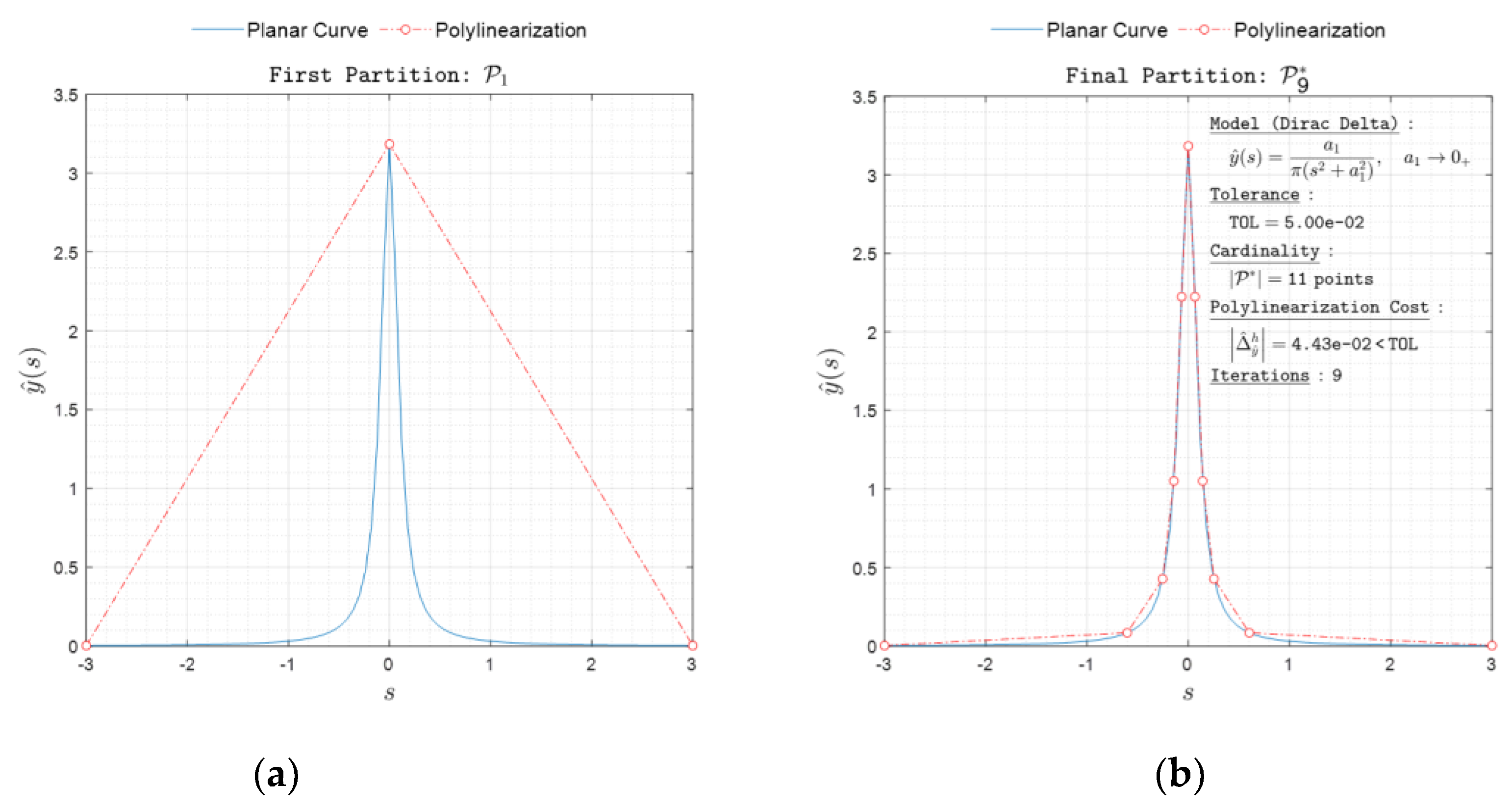

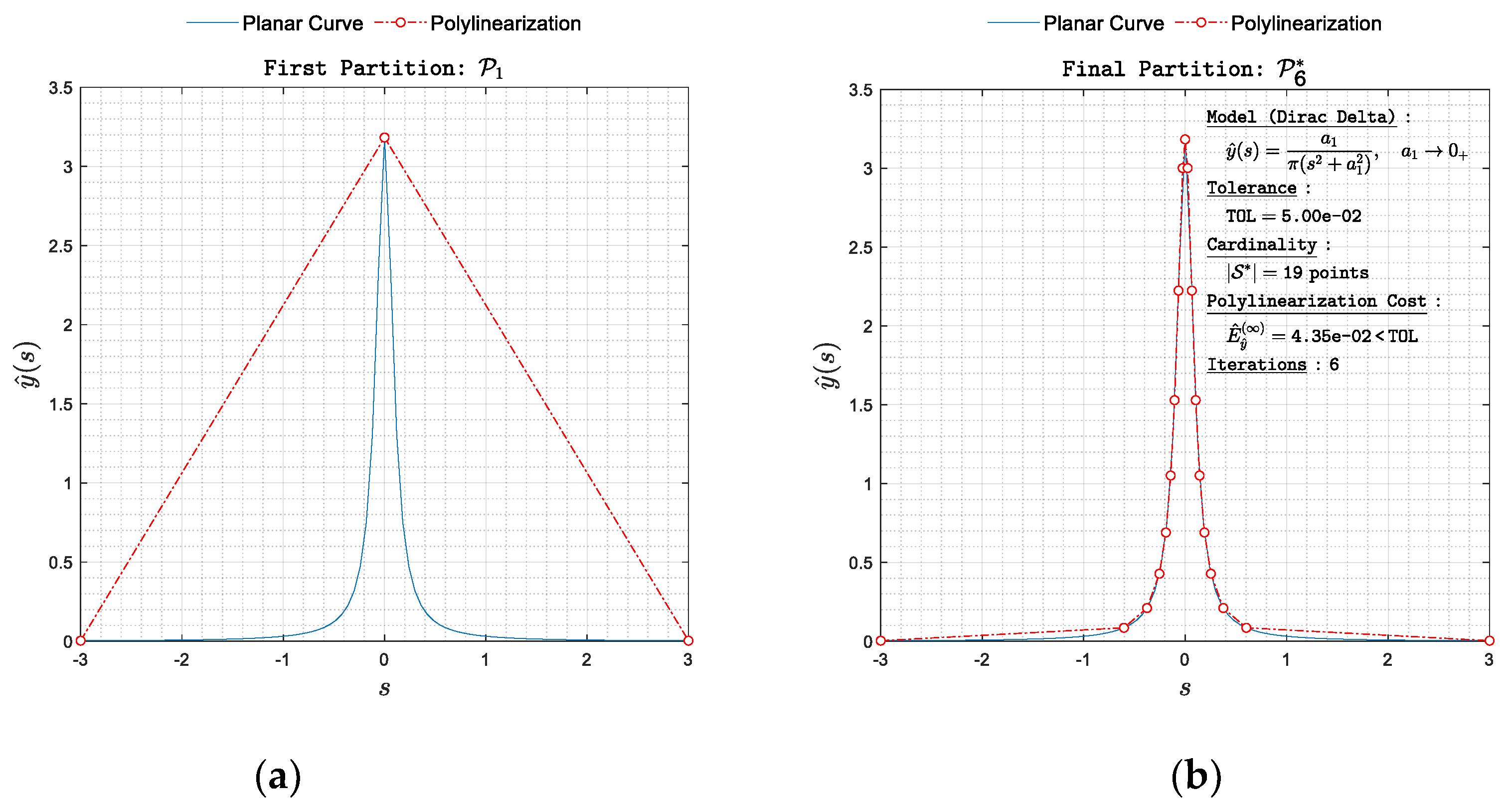

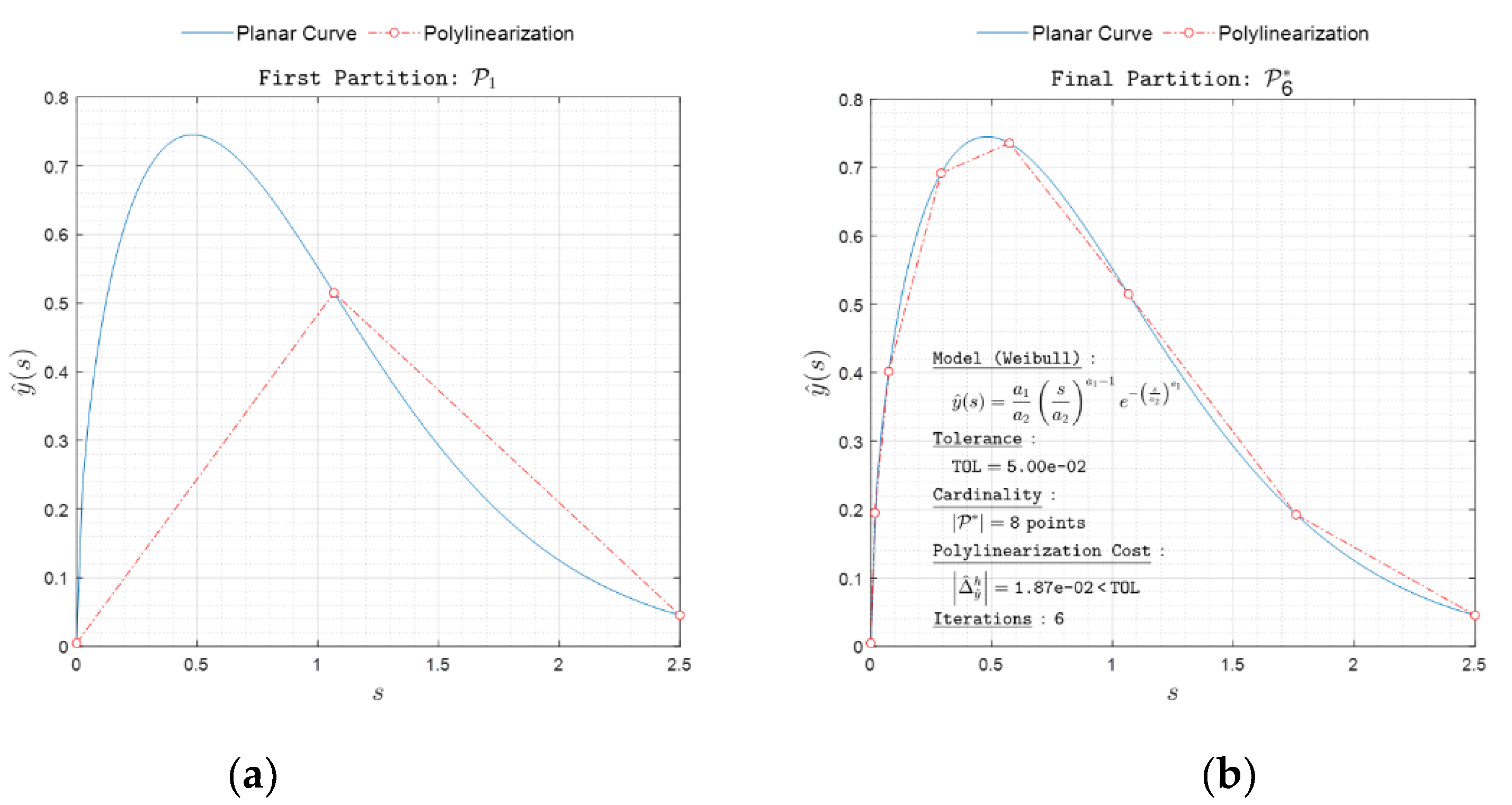

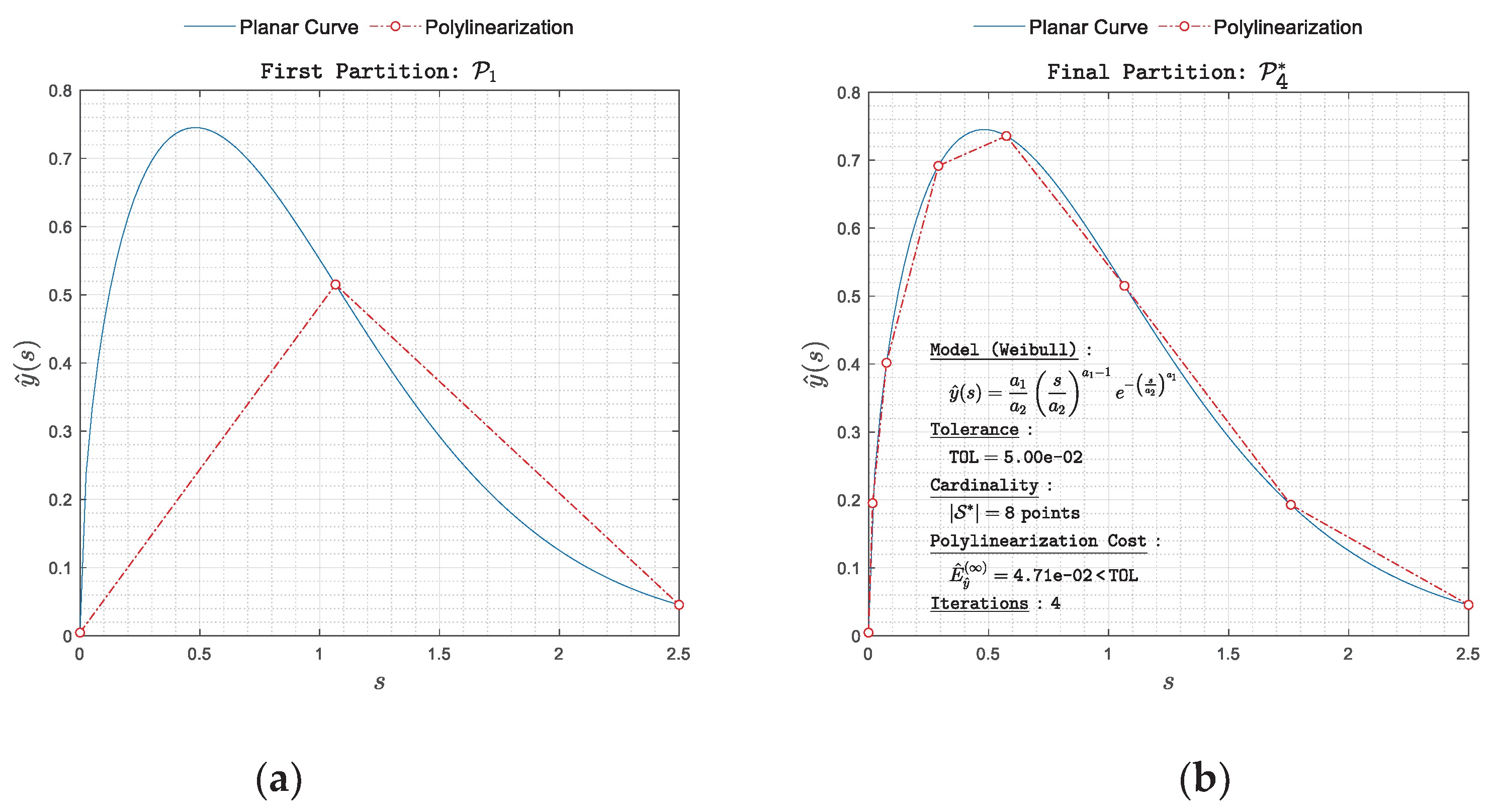

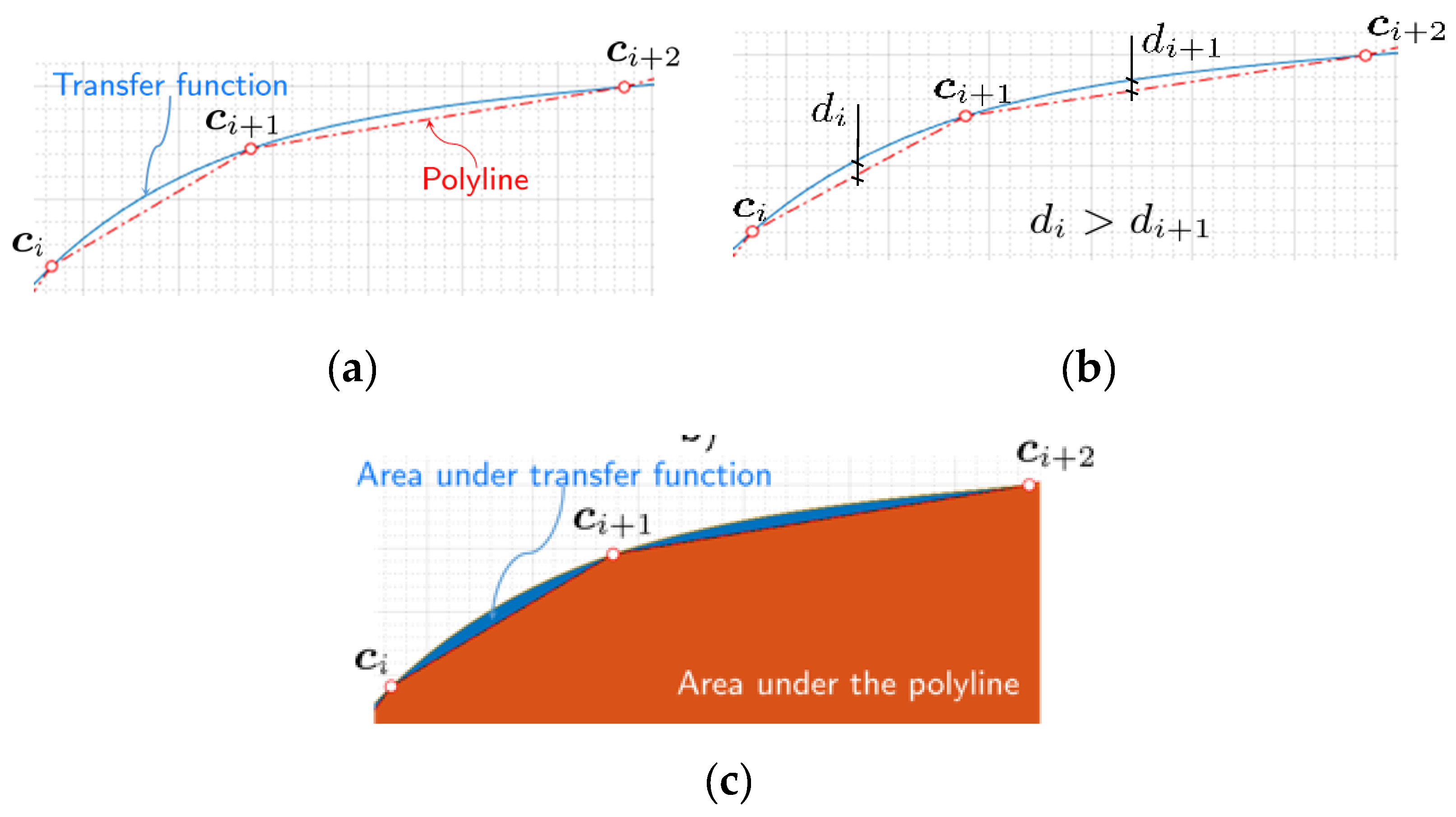

- the surface remoteness, determined for

, as the least upper bound,

with geometric interpretation assisted by

Figure 3a, and

.

the gap, determined for

, and calculated as the largest distance,

with geometric interpretation assisted by

Figure 3b, and

.

For the mesh path

in

Figure 3, the surface remoteness is

Alternatively, the gap satisfies

Whatever the choice of

, however, the behavior of either

or

is always the same, namely: the smaller the remoteness measure for a given mesh

, the closer

is to

. Locally Euclidean manifolds, to which our rectifiable simple curves belong, are better polylinearizable by finer meshes. In the following, we justify this intuitive understanding as deductively correct and show that the remoteness measures (objects inversely proportional to the number of nodes

) provide upper bounds on,

(an object dependent on node locations). Increasing

will decrease the remoteness between

and

. In turn, since the remoteness is an upper bound on

, by increasing

we will further reduce the cost of polylinearization. Let us show this for

. Analogous argumentation can be followed for

. Recall from the previous section that

but

and hence,

Since tends to at a rate proportional to and it therefore follows, that tends to 0 at a rate proportional to , and hence increasing decreases as well, which was necessary to show.

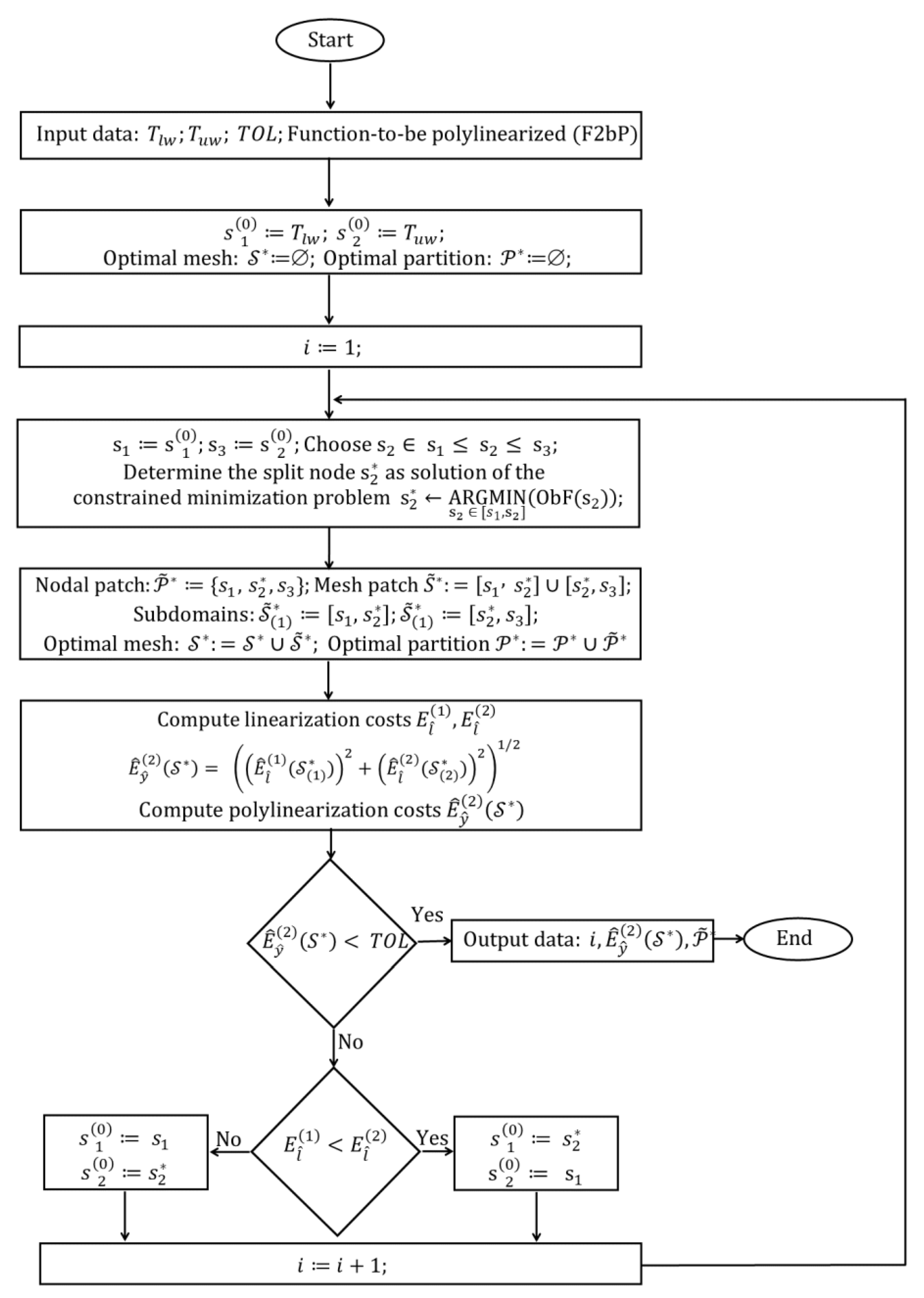

2.3. Optimal Polylinearization of Curves

From all possible meshes , we are interested in calculating the one, say , which minimizes the squared polylinearization cost and decreases , below certain user-defined, tolerance, . Such an objective is therefore twofold: on the one hand, it is related to computing the optimal node locations (topology) in , and on the other hand, it is related to determining the optimal number of nodes, in . A possible formulation of the problem targeting this objective is:

Given

on

and the initial mesh

, determine the optimal mesh

by solving the minimization problem,

Subject to the remoteness-control,

, with

for

or

.

Remarks:

- a)

This problem will be denoted as the optimal polylinearization.

- b)

Control over the nodal locations is enforced by an essential minimization problem for the polylinearization cost, while control over the number of nodes is realized by the corresponding remoteness measure.

- c)

The minimization problem is quadratic, while the remoteness control is not, defined by the corresponding -norm, in which is not equal to . Although qualitatively the remoteness measures behave in the same way - the larger the measure, the more distant the polyline and the curve - quantitatively they differ. Thus, different choices for , will result in different optimal solutions .

- d)

We, therefore, propose the polyline to be always calculated by minimization of polylinearization cost but to interpret particular solutions as optimal only in the context of the imposed remoteness measure.

- e)

The constrained minimization problem admits vectorial interpretation, because which corresponds to , is a vector, whose cardinality and nodal locations, are its solutions, as well.

There are cases where solving the vector minimization problem from the previous section can be effectively reduced to solving a sequence of scalar minimization problems. In this subsection, we consider just such a situation - the polylinearization of rectifiable planar curves. At the onset, fix the origin

and introduce the canonical basis

in

. Let

be the equation of the curve for . Set next, and , with known. For naturally parametrized planar curves alike, the minimization problem from the previous section reads.

Given

on

and the initial mesh

, determine the optimal mesh

by solving the optimization problem of planar polylinearization,

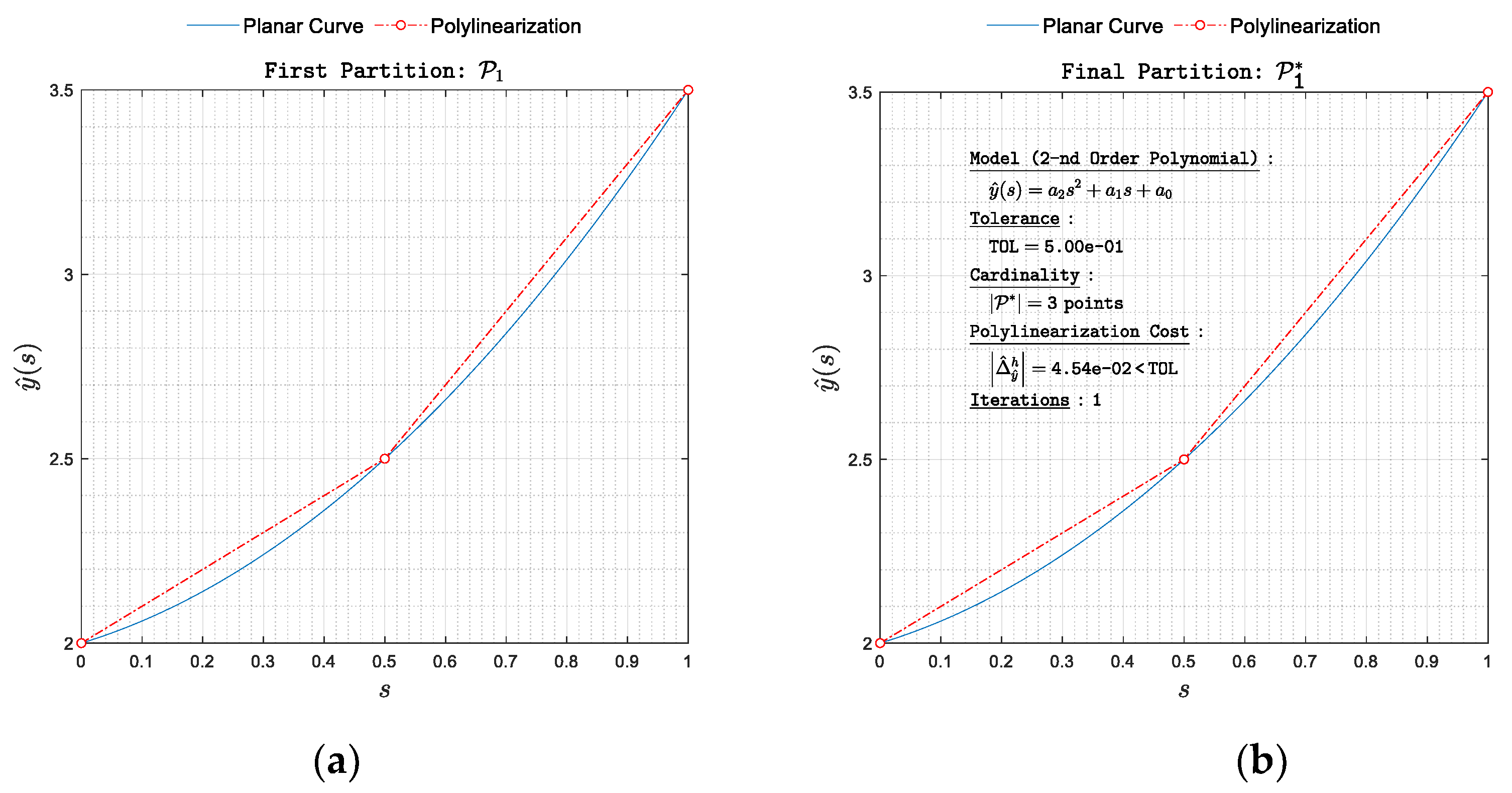

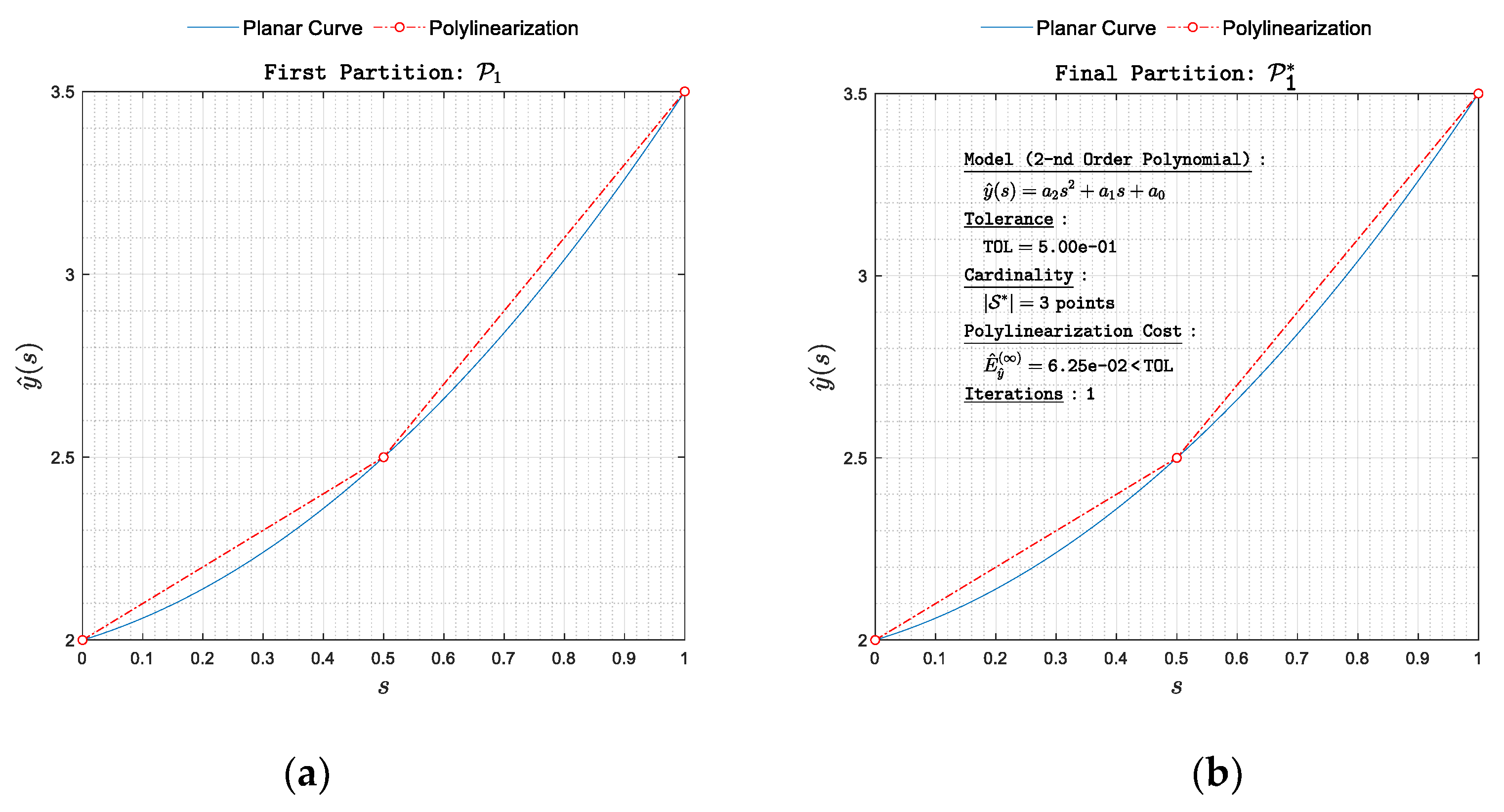

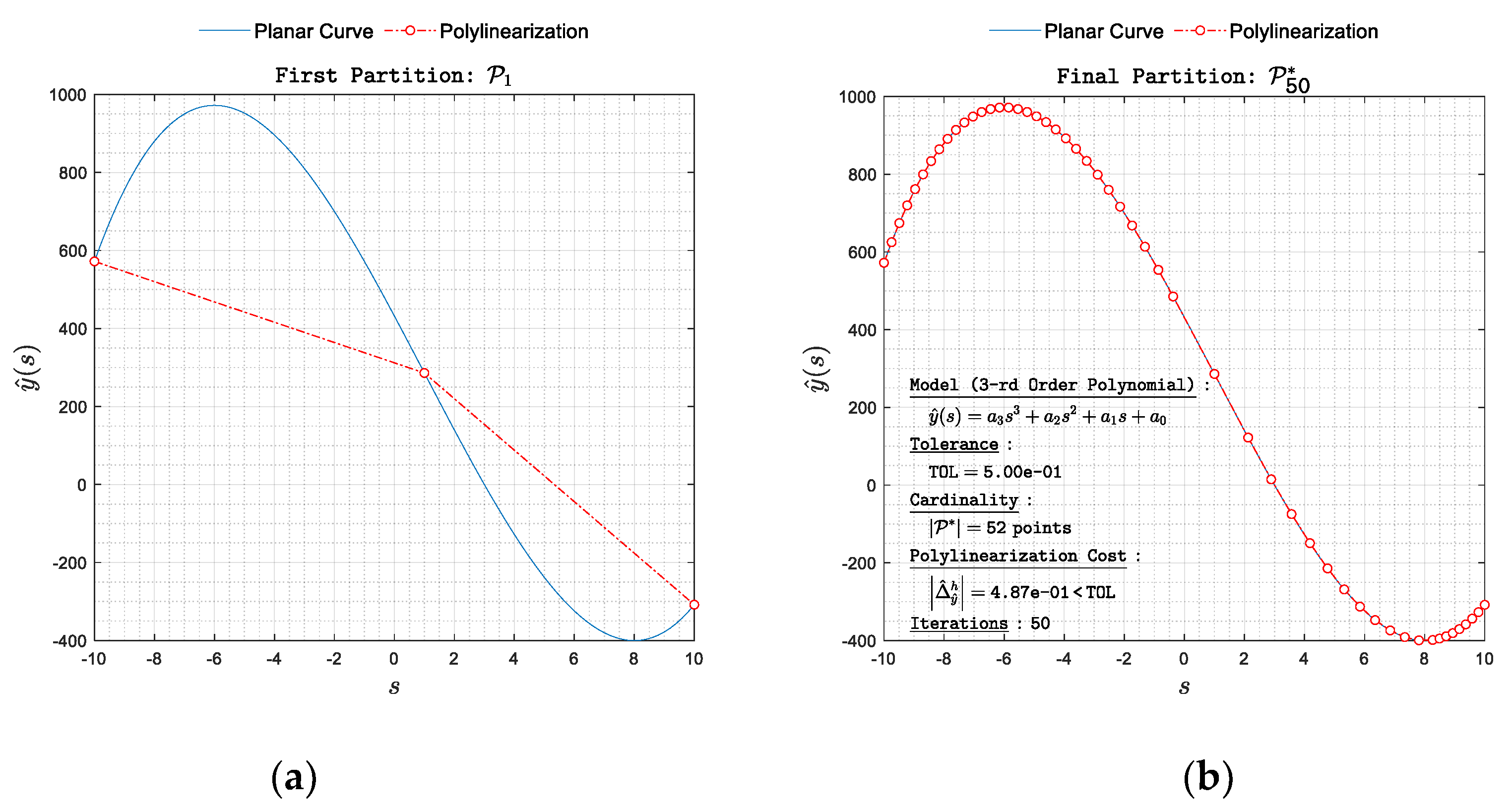

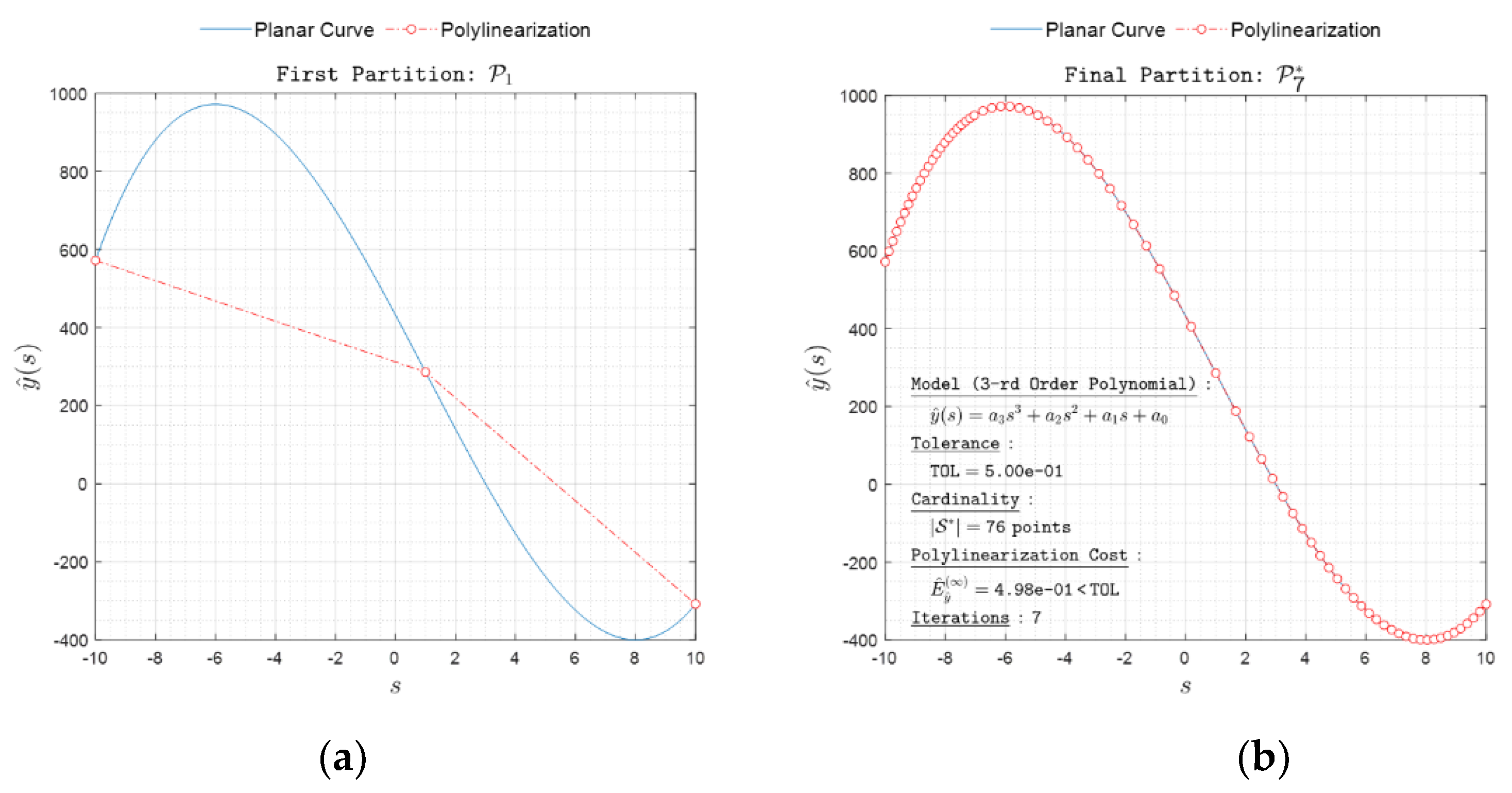

In what follows, we will be interested in calculating for .

The separate contributions to this minimization problem are as follows,

- -

typical, planar line segment,

, on

, has the representation

- -

the linearization cost of

, denoted by

, is

the polylinearization cost,

, is

the surface remoteness is, .

Instead of readily using Lagrangian multiplier to enforce the proximity control on we will approach the solution in a slightly different way. Initialize first the optimal partition and the optimal mesh by accordingly setting: , . The initial partition, with, and is known and fixed. Consider next a nodal patch, , obtained from by adding a node, , of yet unknown location, but between and so that, , and . With the mesh patch, , instilled by , the vector minimization problem with the objective function, , transforms into a scalar minimization problem for with objective function , and constraints, .

Designate the solution of this minimization problem by and the corresponding optimal nodal patch by . The optimal partition, , is next updated with this patch so that, . The split node, , now divides into two subdomains: and , so that the current mesh instilled by is analogously calculated through the update , and consists of . Furthermore, once determined, the mesh allows us to compute and compare it with TOL. If , we are done, otherwise if , we need to add more nodes between and , and compute their location by constrained minimization. Suppose the latter happened.

In which of the subdomains

or

to add new split node(s)? On the one hand, we do not want to add unnecessarily many nodes, on the other we do not want to add too few. The former requires more storage space while the latter requires more computational time. Let’s agree to add no more than one node per interval and focus on how to select the appropriate interval. The reliable selection criterion is provided by the largest surface remoteness, determined over the current set of subdomains in the mesh, i.e. the candidate subdomains for splitting are those whose surface remoteness is the largest, or

In our particular case,

splits

into two subdomains with surface remotenesses

Assume for the sake of clarity that the whose is the largest corresponds to , and overwrite , by and .

Analogous to what we did before, construct

from

by allocating a node,

between

and

so that for

, we again have

,

, and

. Consider

unknown and determine it by constrained minimization of

, thus updating the optimal nodal patch

and the mesh patch,

Further, with

and

yet updated, we update the optimal partition and the optimal mesh:

,

, so that

Once we have , we compute again and compare it with . If we stop the computation, otherwise we repeat again the surface-remoteness-based approach for the selection of the next candidate subdomain for splitting. In the above procedure, it is easy to notice that: first, the sequence of points is generated as a solution to the corresponding sequence of constrained minimization problems for the unknown ; and second, each minimization problem in this sequence is solved over a subdomain with fixed ends.

The main steps of the developed algorithm are shown in

Figure 4.