Submitted:

22 February 2024

Posted:

27 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and methods

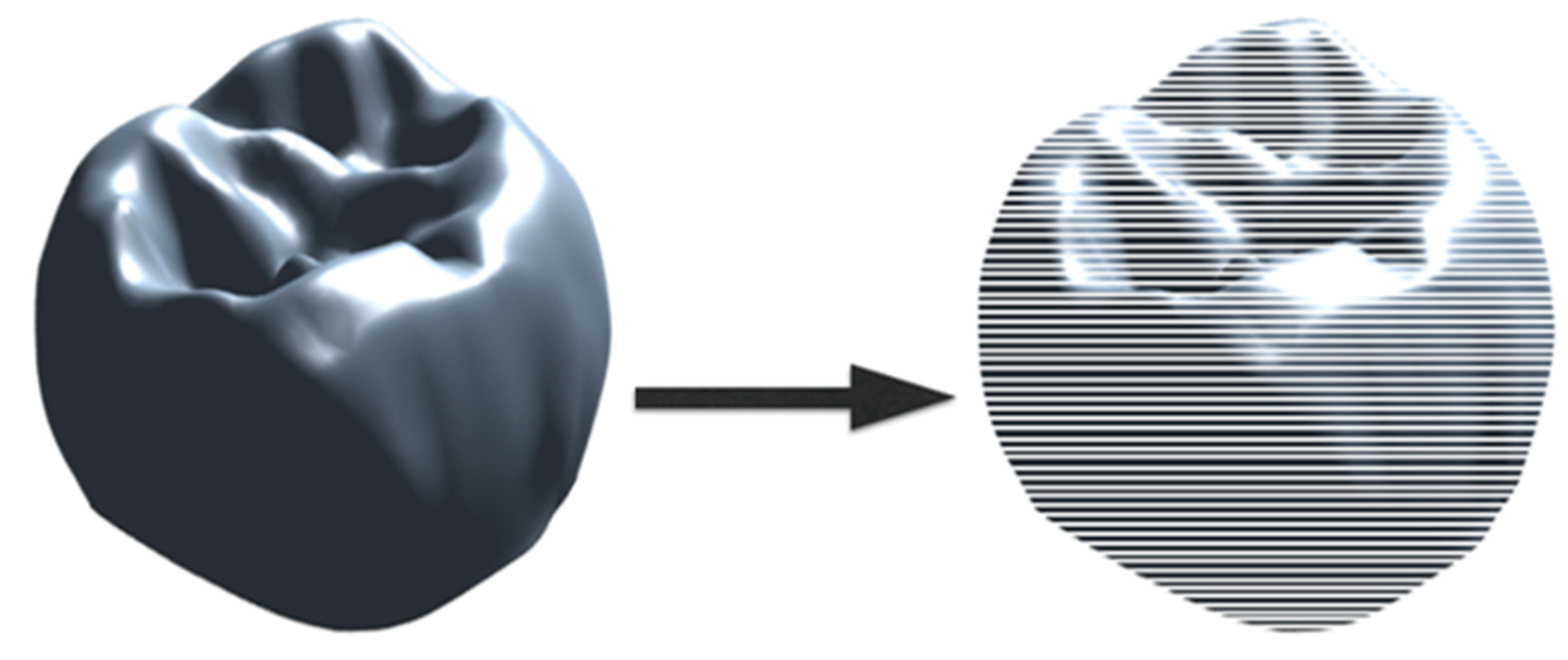

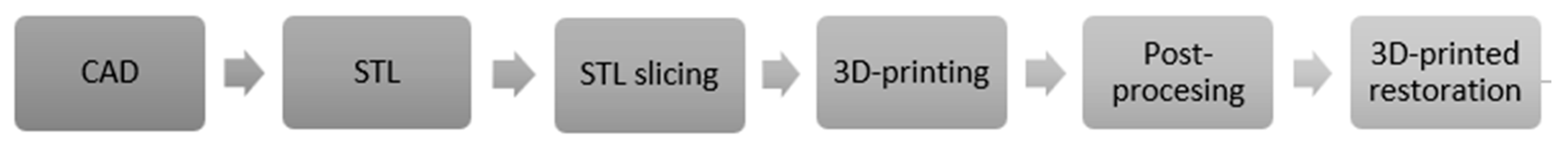

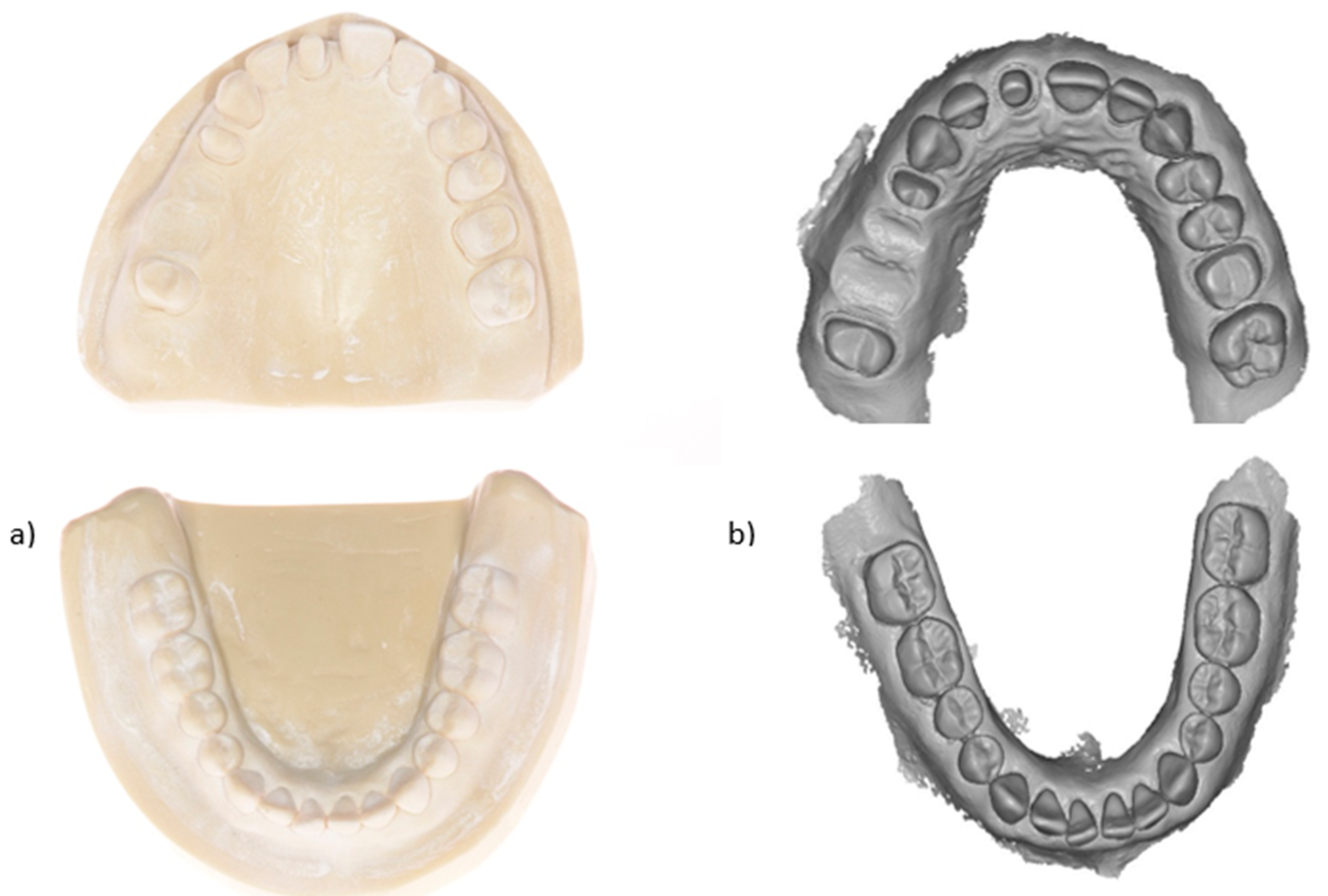

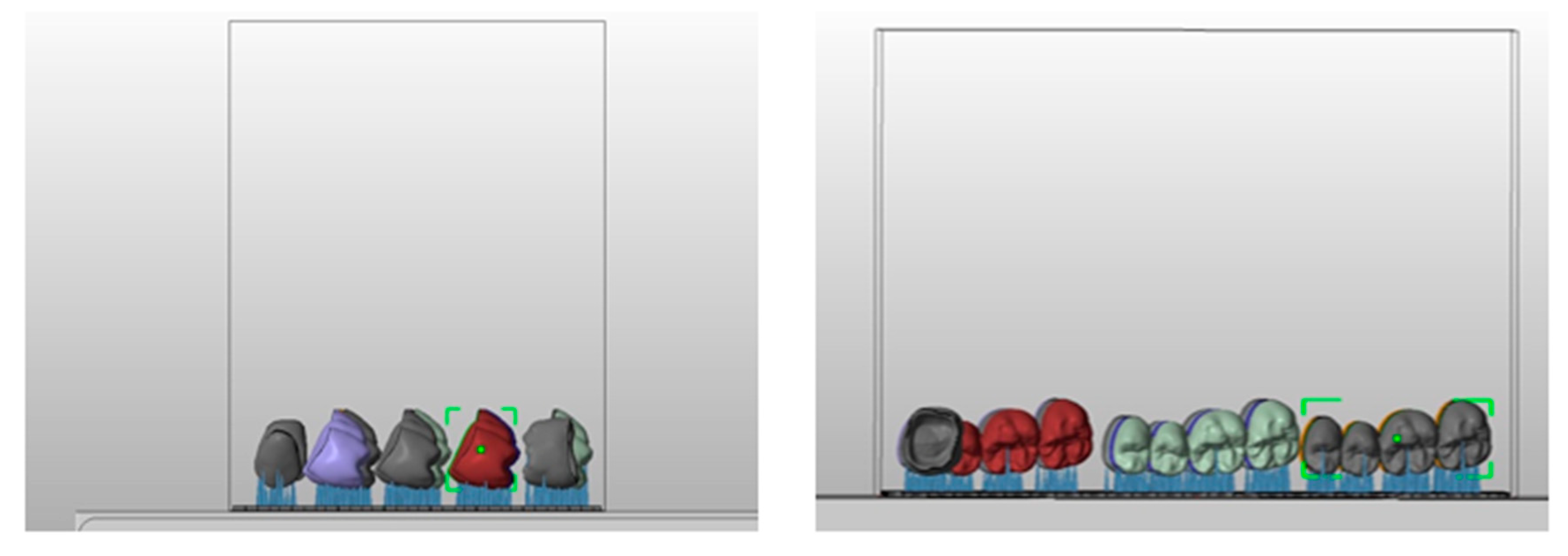

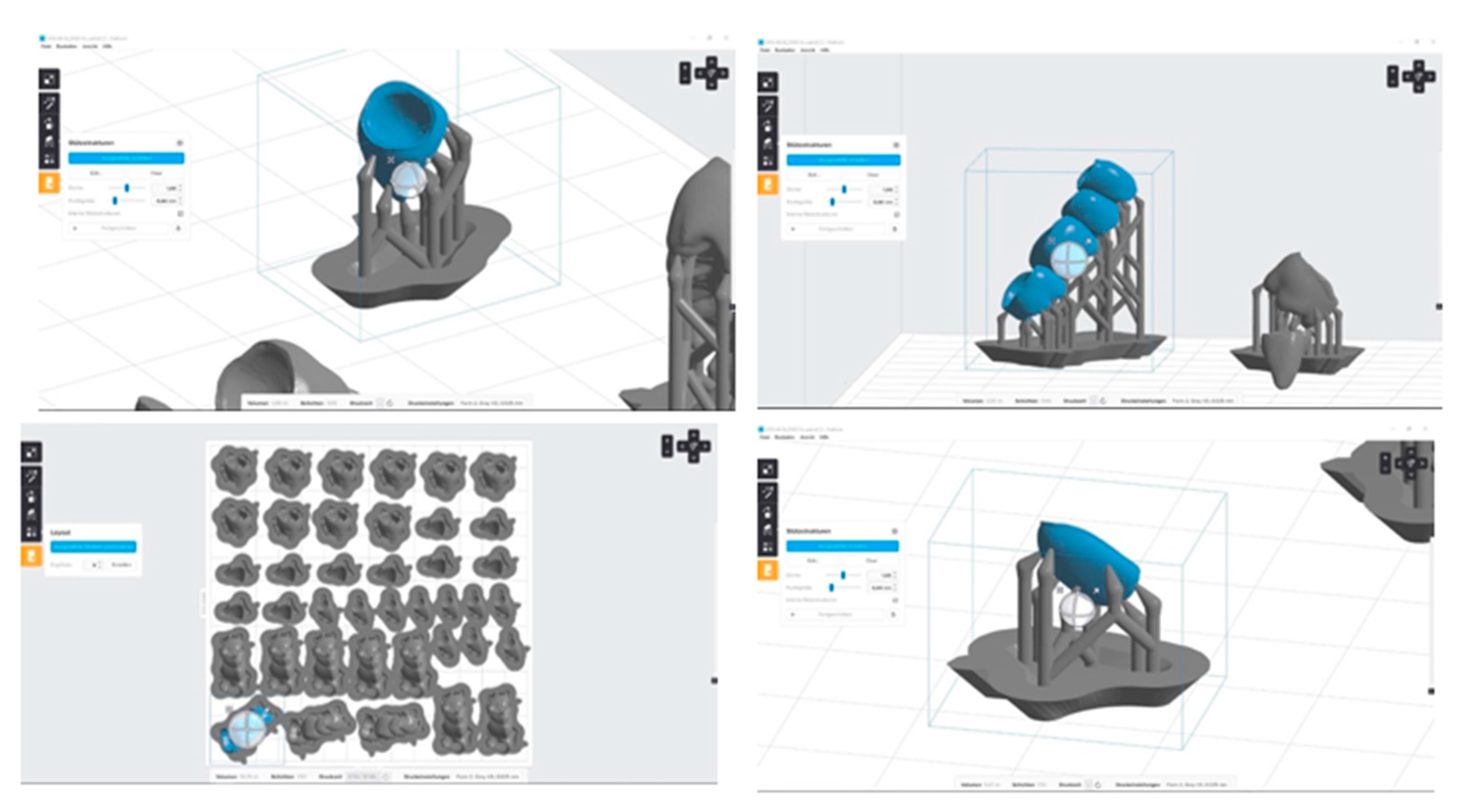

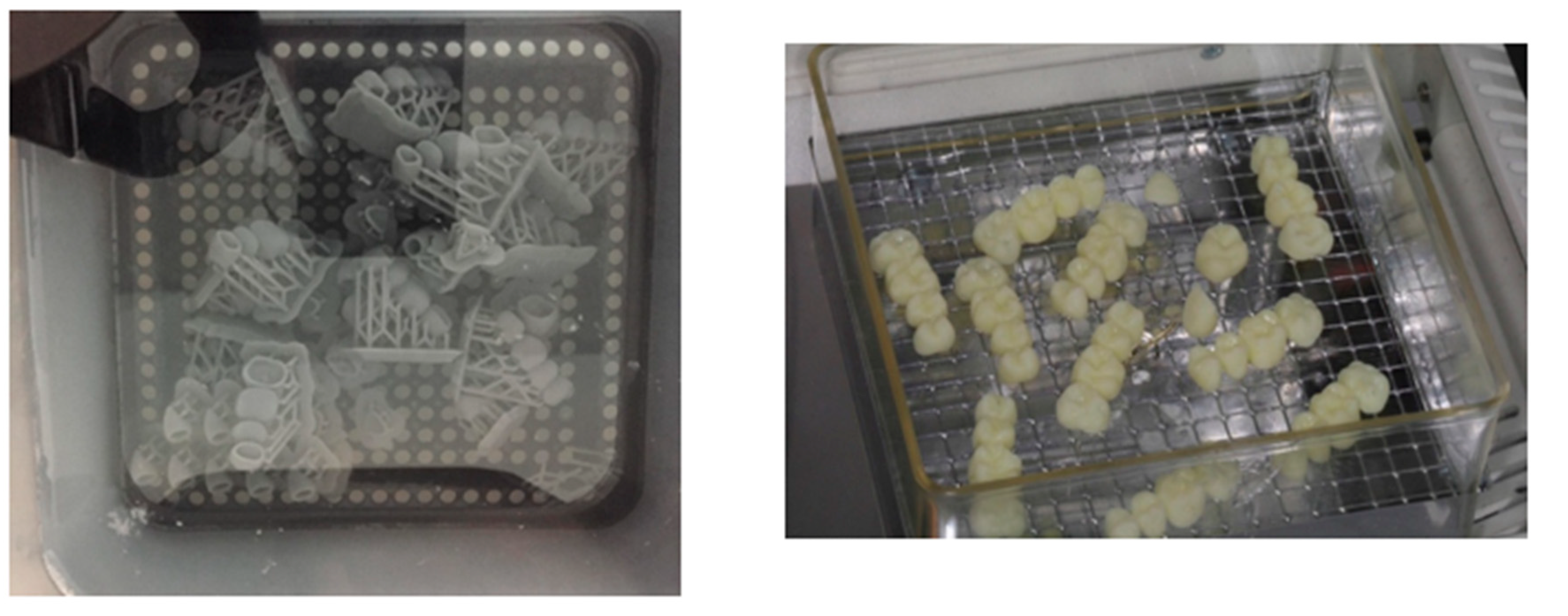

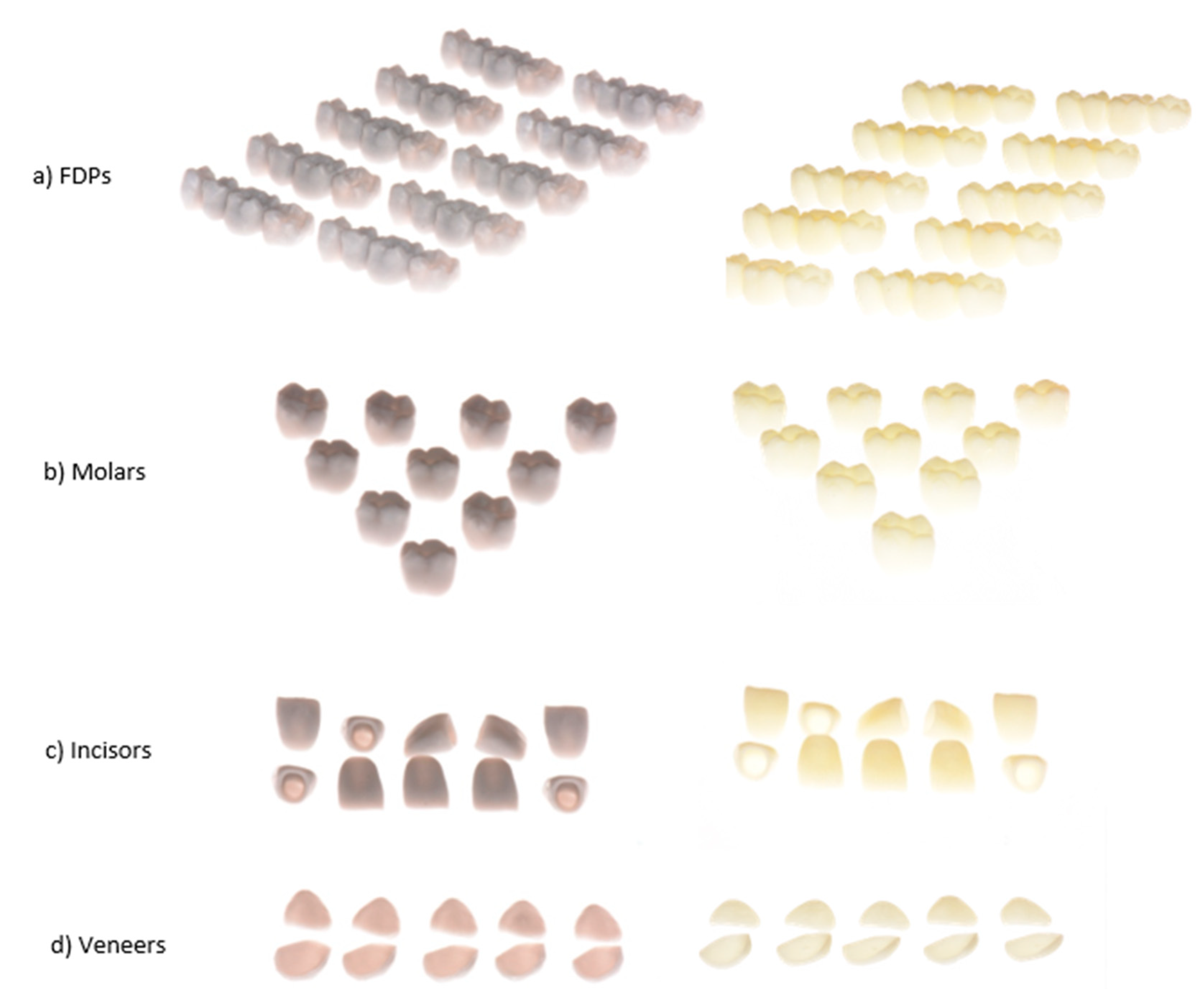

2.13. D-Printing Process

2.2. Data Analysis

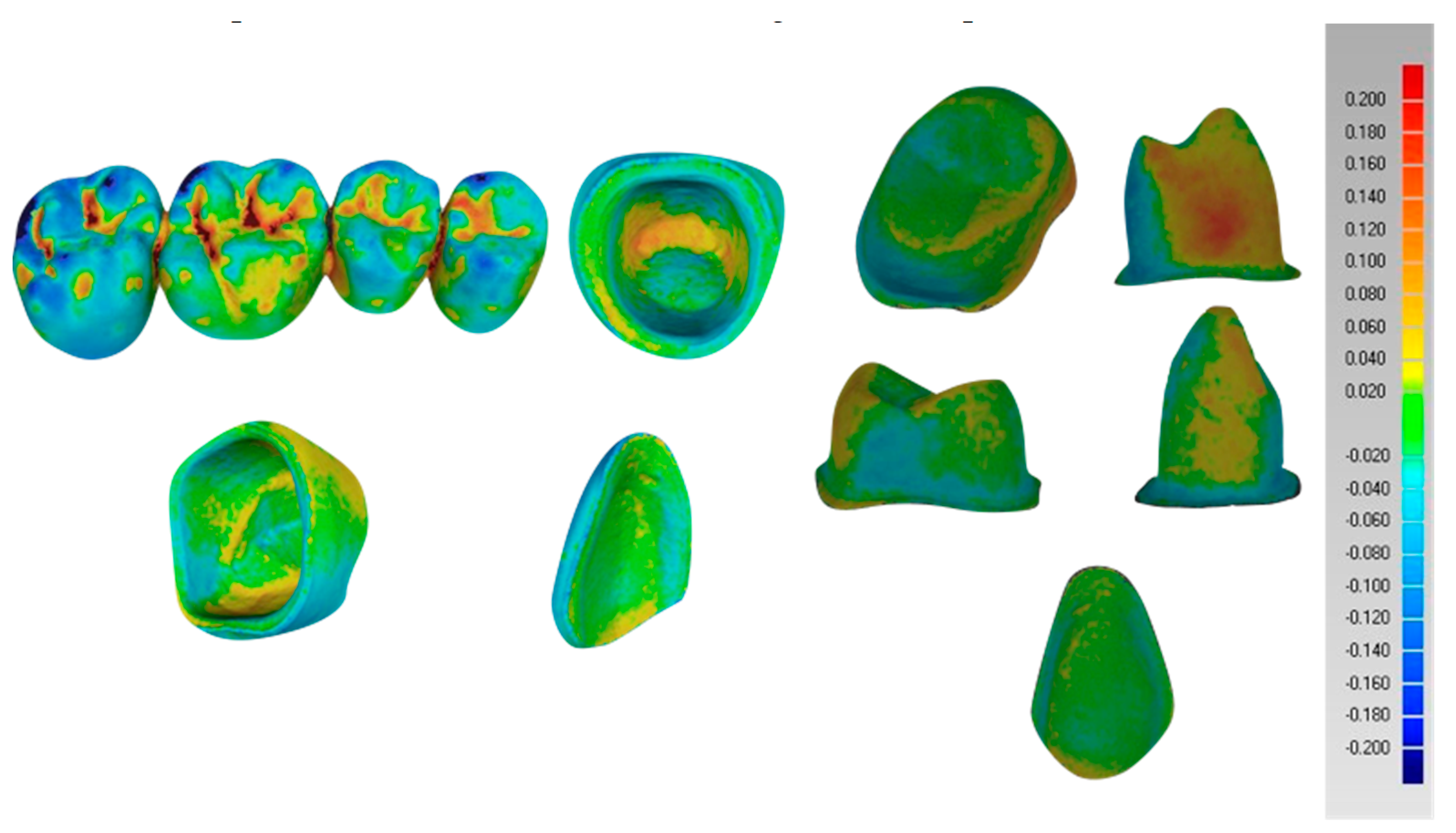

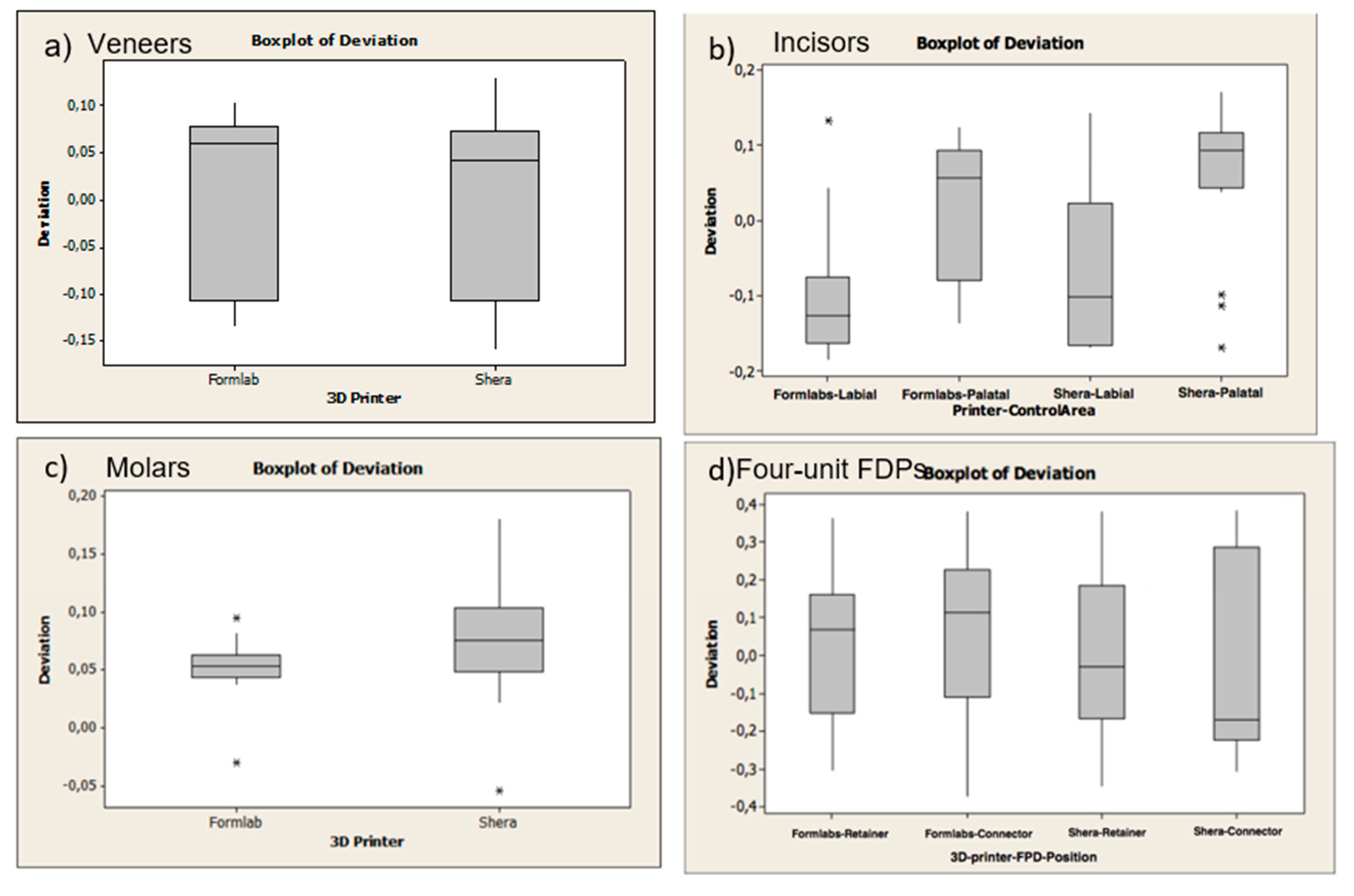

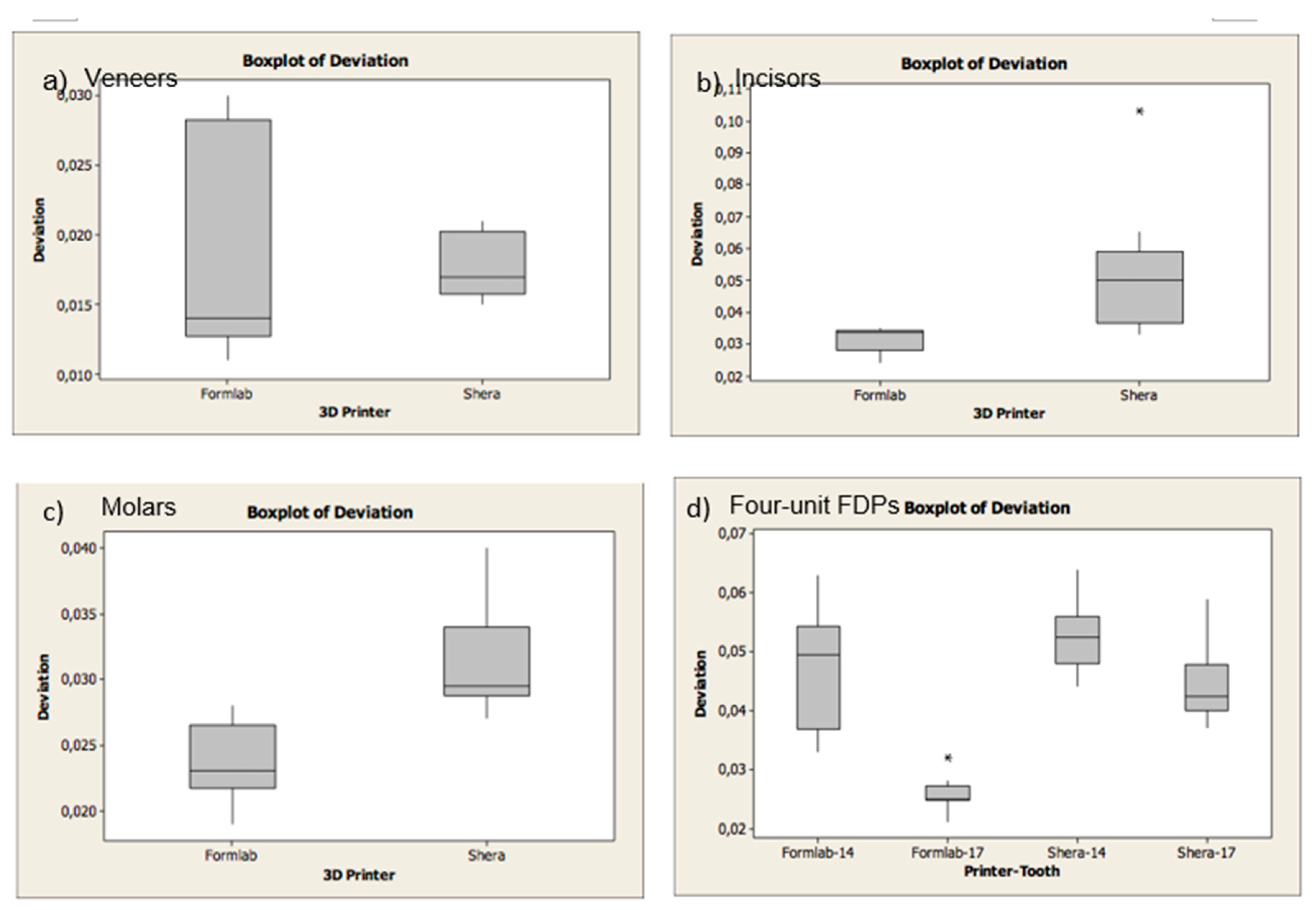

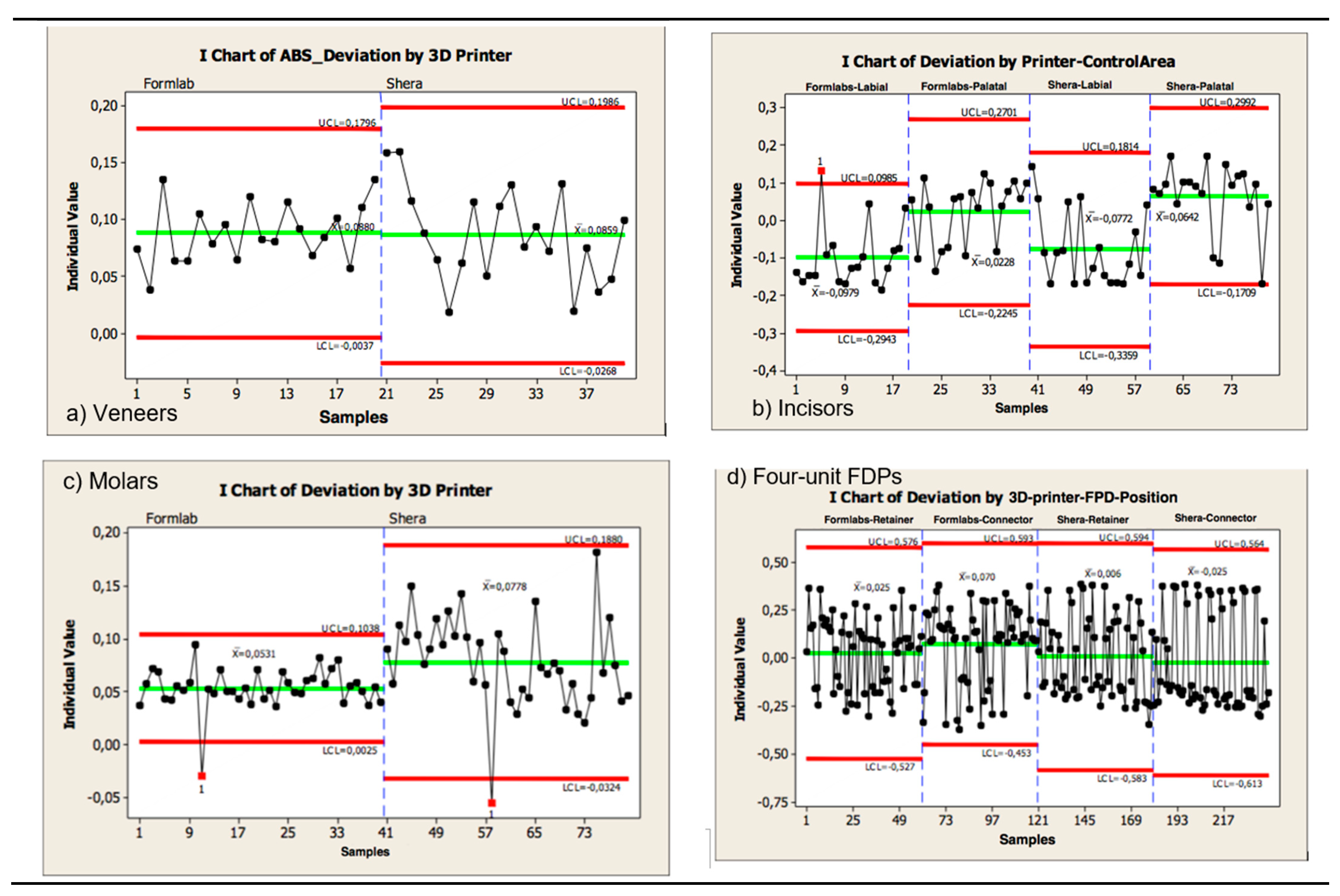

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Ahmed, K. E. We're going digital: the current state of CAD/CAM dentistry in prosthodontics. Primary Dental Journal 2018, 7, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenghi, L.; Barenghi, A.; Garagiola, U.; Di Blasio, A.; Giannì, A. B.; Spadari, F. Pros and cons of CAD/CAM technology for infection prevention in dental settings during COVID-19 outbreak. Sensors 2021, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suese, K. Progress in digital dentistry: The practical use of intraoral scanners. Dental Materials Journal 2020, 39, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R. S.; Hoye, L. N.; Elnagar, M. H.; Atsawasuwan, P.; Galang-Boquiren, M. T.; Caplin, J.; Viana, G. C.; Obrez, A.; Kusnoto, B. Accuracy of Dental Monitoring 3D digital dental models using photograph and video mode. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2019, 156, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Hotta, Y.; Kunii, J.; Kuriyama, S.; Tamaki, Y. A review of dental CAD/CAM: current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience. Dental materials journal 2009, 28, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, K. J.; Morgano, S. M.; Driscoll, C. F.; Freilich, M. A.; Guckes, A. D.; Knoernschild, K. L.; McGarry, T. J.; Twain, M. The glossary of prosthodontic terms. 2017.

- Beuer, F.; Schweiger, J.; Edelhoff, D. Digital dentistry: an overview of recent developments for CAD/CAM generated restorations. British dental journal 2008, 204, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, J.; Edelhoff, D.; Güth, J.-F. 3D printing in digital prosthetic dentistry: an overview of recent developments in additive manufacturing. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noort, R. The future of dental devices is digital. Dental materials 2012, 28, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joerg, R. Computer-aided design and fabrication of dental restorations. Journal of American dental association 2006, 137, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, M. The use of cutting temperature to evaluate the machinability of titanium alloys. Acta biomaterialia 2009, 5, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samra, A. P. B.; Morais, E.; Mazur, R. F.; Vieira, S. R.; Rached, R. N. CAD/CAM in dentistry–a critical review. Revista Odonto Ciência 2016, 31, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braian, M.; Jönsson, D.; Kevci, M.; Wennerberg, A. Geometrical accuracy of metallic objects produced with additive or subtractive manufacturing: A comparative in vitro study. Dental Materials 2018, 34, 978–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glossary of Digital Dental Terms. 2nd Edition. Journal of Prosthodontics 2021, 30, 172–181.

- Torii, M.; Nakata, T.; Takahashi, K.; Kawamura, N.; Shimpo, H.; Ohkubo, C. Fitness and retentive force of cobalt-chromium alloy clasps fabricated with repeated laser sintering and milling. journal of prosthodontic research 2018, 62, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, T.; Shimpo, H.; Ohkubo, C. Clasp fabrication using one-process molding by repeated laser sintering and high-speed milling. Journal of prosthodontic research 2017, 61, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, T.; Zheng, E. History of 3D printing. 2016.

- Huang, Y.; Leu, M. C.; Mazumder, J.; Donmez, A. Additive manufacturing: current state, future potential, gaps and needs, and recommendations. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering 2015, 137, 014001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International organization for standardization. ISO/ASTM 52900:2015 (ASTM F2792). 2019.

- Kruth, J.-P.; Leu, M.-C.; Nakagawa, T. Progress in additive manufacturing and rapid prototyping. Cirp Annals 1998, 47, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-León, M.; Özcan, M. Additive manufacturing technologies used for processing polymers: current status and potential application in prosthetic dentistry. Journal of Prosthodontics 2019, 28, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-León, M.; Sadeghpour, M.; Özcan, M. An update on applications of 3D printing technologies used for processing polymers used in implant dentistry. Odontology 2020, 108, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-León, M.; Meyer, M. J.; Özcan, M. Metal additive manufacturing technologies: literature review of current status and prosthodontic applications. Int. J. Comput. Dent 2019, 22, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Revilla-León, M.; Meyer, M. J.; Zandinejad, A.; Özcan, M. Additive manufacturing technologies for processing zirconia in dental applications. Int J Comput Dent 2020, 23, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, P. F. Stereolithography and other RP&M technologies: from rapid prototyping to rapid tooling. Society of Manufacturing Engineers: 1995.

- Ian Gibson, I. G. Additive manufacturing technologies 3D printing, rapid prototyping, and direct digital manufacturing. Springer: 2015.

- Alammar, A.; Kois, J. C.; Revilla-León, M.; Att, W. Additive manufacturing technologies: current status and future perspectives. Journal of Prosthodontics 2022, 31, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, N.; Alharbi, S.; Cuijpers, V. M.; Osman, R. B.; Wismeijer, D. Three-dimensional evaluation of marginal and internal fit of 3D-printed interim restorations fabricated on different finish line designs. Journal of prosthodontic research 2018, 62, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahayeri, A.; Morgan, M.; Fugolin, A. P.; Bompolaki, D.; Athirasala, A.; Pfeifer, C. S.; Ferracane, J. L.; Bertassoni, L. E. 3D printed versus conventionally cured provisional crown and bridge dental materials. Dental materials 2018, 34, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.; Sim, J.-Y.; Park, J.-K.; Kim, W.-C.; Kim, H.-Y.; Kim, J.-H. Accuracy of 3-unit fixed dental prostheses fabricated on 3D-printed casts. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry 2020, 123, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rungrojwittayakul, O.; Kan, J. Y.; Shiozaki, K.; Swamidass, R. S.; Goodacre, B. J.; Goodacre, C. J.; Lozada, J. L. Accuracy of 3D printed models created by two technologies of printers with different designs of model base. Journal of Prosthodontics 2020, 29, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joda, T.; Matthisson, L.; Zitzmann, N. U. Impact of aging on the accuracy of 3D-printed dental models: an in vitro investigation. Journal of clinical medicine 2020, 9, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantea, M.; Ciocoiu, R. C.; Greabu, M.; Ripszky Totan, A.; Imre, M.; Țâncu, A. M. C.; Sfeatcu, R.; Spînu, T. C.; Ilinca, R.; Petre, A. E. Compressive and flexural strength of 3D-printed and conventional resins designated for interim fixed dental prostheses: An in vitro comparison. Materials 2022, 15, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellakany, P.; Fouda, S. M.; Mahrous, A. A.; AlGhamdi, M. A.; Aly, N. M. Influence of CAD/CAM milling and 3d-printing fabrication methods on the mechanical properties of 3-unit interim fixed dental prosthesis after thermo-mechanical aging process. Polymers 2022, 14, 4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-M.; Park, J.-M.; Kim, S.-K.; Heo, S.-J.; Koak, J.-Y. Flexural strength of 3D-printing resin materials for provisional fixed dental prostheses. Materials 2020, 13, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Wadei, M. H. D.; Sayed, M. E.; Jain, S.; Aggarwal, A.; Alqarni, H.; Gupta, S. G.; Alqahtani, S. M.; Alahmari, N. M.; Alshehri, A. H.; Jain, M. Marginal Adaptation and Internal Fit of 3D-Printed Provisional Crowns and Fixed Dental Prosthesis Resins Compared to CAD/CAM-Milled and Conventional Provisional Resins: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Coatings 2022, 12, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güth, J.-F.; Edelhoff, D.; Schweiger, J.; Keul, C. A new method for the evaluation of the accuracy of full-arch digital impressions in vitro. Clinical oral investigations 2016, 20, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, H.; Hatakeyama, W.; Komine, F.; Takafuji, K.; Takahashi, T.; Yokota, J.; Oriso, K.; Kondo, H. Accuracy and practicality of intraoral scanner in dentistry: A literature review. Journal of prosthodontic research 2020, 64, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patzelt, S. B.; Bishti, S.; Stampf, S.; Att, W. Accuracy of computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing–generated dental casts based on intraoral scanner data. The Journal of the American Dental Association 2014, 145, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patzelt, S. B.; Emmanouilidi, A.; Stampf, S.; Strub, J. R.; Att, W. Accuracy of full-arch scans using intraoral scanners. Clinical oral investigations 2014, 18, 1687–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacher, M.; Schulz, G.; Deyhle, H.; Jäger, K.; Müller, B. Accuracy of commercial intraoral scanners. Journal of Medical Imaging 2021, 8, 035501–035501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hack, G. D.; Patzelt, S. Evaluation of the accuracy of six intraoral scanning devices: an in-vitro investigation. ADA Prof Prod Rev 2015, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Vandeweghe, S.; Vervack, V.; Dierens, M.; De Bruyn, H. Accuracy of digital impressions of multiple dental implants: an in vitro study. Clinical oral implants research 2017, 28, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattamavilai, S.; Ongthiemsak, C. Accuracy of intraoral scanners in different complete arch scan patterns. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornvit, P.; Rokaya, D.; Sanohkan, S. Comparison of accuracy of current ten intraoral scanners. BioMed Research International 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Bona, A.; Cantelli, V.; Britto, V. T.; Collares, K. F.; Stansbury, J. W. 3D printing restorative materials using a stereolithographic technique: A systematic review. Dental Materials 2021, 37, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.; Osman, R. B.; Wismeijer, D. Factors Influencing the Dimensional Accuracy of 3D-Printed Full-Coverage Dental Restorations Using Stereolithography Technology. The International journal of prosthodontics 2016, 29, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. B.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Yang, D. H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kyung, Y. S.; Kim, C.-S.; Choi, S. H.; Kim, B. J.; Ha, H. Three-dimensional printing: basic principles and applications in medicine and radiology. Korean journal of radiology 2016, 17, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contrepois, M.; Soenen, A.; Bartala, M.; Laviole, O. Marginal adaptation of ceramic crowns: a systematic review. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry 2013, 110, 447–454.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R. C.; Liu, P.-R.; Reddy, M. S. An Advanced Fiber-Reinforced Composite Solution for Gingival Inflammation and Bone Loss Related to Restorative Crowns. EC dental science 2020, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Att, W.; Komine, F.; Gerds, T.; Strub, J. R. Marginal adaptation of three different zirconium dioxide three-unit fixed dental prostheses. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry 2009, 101, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rifaiy, M. Evaluation of vertical marginal adaptation of provisional crowns by digital microscope. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice 2017, 20, 1610–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, J. The estimation of cement film thickness by an in vivo technique. British dental journal 1971, 131, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikova, T.; Dzhendov, D.; Katreva, I.; Pavlova, D. Accuracy of polymeric dental bridges manufactured by stereolithography. Arch Mater Sci Eng 2016, 78, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Miyasaka, T. Dimensional accuracy of dental casting patterns created by 3D printers. Dental materials journal 2016, 35, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Son, J.-W.; Jang, J.-H.; Choi, S.-H.; Jang, W.-H.; Lee, B.-N.; Park, C. Comparing volumetric and biological aspects of 3D-printed interim restorations under various post-curing modes. The Journal of Advanced Prosthodontics 2021, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G. K.; Gallucci, G. O.; Lee, S. J. Accuracy in the digital workflow: from data acquisition to the digitally milled cast. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry 2016, 115, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badanova, N.; Perveen, A.; Talamona, D. Study of SLA Printing Parameters Affecting the Dimensional Accuracy of the Pattern and Casting in Rapid Investment Casting. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2022, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Monsees, D.; Hey, J.; Schweyen, R. Surface quality of 3D-printed models as a function of various printing parameters. Materials 2019, 12, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.-S.; Kim, S.-K.; Heo, S.-J.; Koak, J.-Y.; Seo, D.-G. Effects of printing parameters on the fit of implant-supported 3D printing resin prosthetics. Materials 2019, 12, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unkovskiy, A.; Bui, P. H.-B.; Schille, C.; Geis-Gerstorfer, J.; Huettig, F.; Spintzyk, S. Objects build orientation, positioning, and curing influence dimensional accuracy and flexural properties of stereolithographically printed resin. Dental Materials 2018, 34, e324–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hada, T.; Kanazawa, M.; Iwaki, M.; Arakida, T.; Soeda, Y.; Katheng, A.; Otake, R.; Minakuchi, S. Effect of printing direction on the accuracy of 3D-printed dentures using stereolithography technology. Materials 2020, 13, 3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P.; Allen, S.; Dutta, D. Part orientation and build cost determination in layered manufacturing. Computer-Aided Design 1998, 30, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Bloomstein, R. D.; Briss, D.; Holland, J. N.; Morsy, H. M.; Kasper, F. K.; Huang, W. Effect of build angle and layer height on the accuracy of 3-dimensional printed dental models. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2021, 160, 451–458.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-M.; Park, J.-M.; Kim, S.-K.; Heo, S.-J.; Koak, J.-Y. Comparison of flexural strength of three-dimensional printed three-unit provisional fixed dental prostheses according to build directions. Journal of Korean Dental Science 2019, 12, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Çakmak, G.; Cuellar, A. R.; Donmez, M. B.; Abou-Ayash, S.; Lu, W.-E.; Schimmel, M.; Yilmaz, B. Effect of printing layer thickness on the trueness of 3-unit interim fixed partial dentures. The journal of prosthetic dentistry 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharat, S. S.; Tatikonda, A.; Raina, S.; Gubrellay, P.; Gupta, N.; Asopa, S. J. In vitro evaluation of the accuracy of seating cast metal fixed partial denture on the abutment teeth with varying degree of convergence angle. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, 2015; 9, ZC56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.-c.; Li, P.-l.; Chu, F.-t.; Shen, G. Influence of the three-dimensional printing technique and printing layer thickness on model accuracy. Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics/Fortschritte der Kieferorthopadie.

- You, S.-M.; You, S.-G.; Kang, S.-Y.; Bae, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-H. Evaluation of the accuracy (trueness and precision) of a maxillary trial denture according to the layer thickness: An in vitro study. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry 2021, 125, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, A. A.; Raju, R.; Ellakwa, A. Effect of printing layer thickness and postprinting conditions on the flexural strength and hardness of a 3D-printed resin. BioMed Research International 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Donmez, M. B.; Kahveci, Ç.; Cuellar, A. R.; de Paula, M. S.; Schimmel, M.; Abou-Ayash, S.; Çakmak, G. Effect of printing layer thickness on the trueness and fit of additively manufactured removable dies. The journal of prosthetic dentistry 2022, 128, 1318.e1–1318.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favero, C. S.; English, J. D.; Cozad, B. E.; Wirthlin, J. O.; Short, M. M.; Kasper, F. K. Effect of print layer height and printer type on the accuracy of 3-dimensional printed orthodontic models. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2017, 152, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaleli, N.; Ural, Ç.; Özköylü, G.; Duran, İ. Effect of layer thickness on the marginal and internal adaptation of laser-sintered metal frameworks. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2019, 121, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasan, D.; Legaz, J.; Boitelle, P.; Mojon, P.; Fehmer, V.; Sailer, I. Accuracy of Additively Manufactured and Milled Interim 3-Unit Fixed Dental Prostheses. Journal of Prosthodontics 2022, 31, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

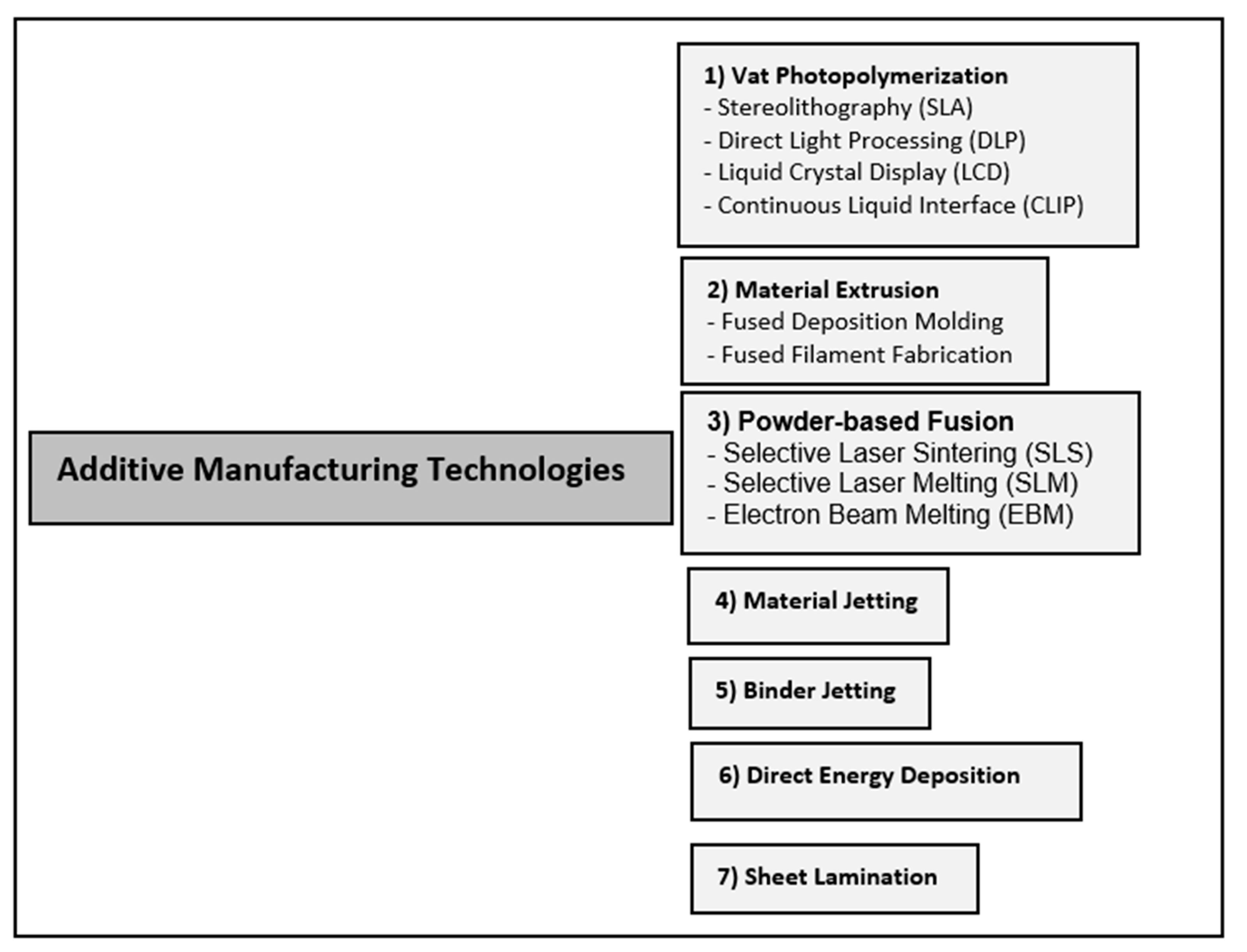

| Material | 3D-printing Technology | Dental Applications |

|---|---|---|

|

Polymer-based: - Castable Resins - Hard Polymer - Clear Hard Polymers - Resin Composite Tooth Shade - Resin Composite Gingiva Elastic Shade - Waxes - Polyethylene - Polylactic Acid - Polycarbonate - Polysulfide - Polycaprolactone - ABS - PEEK* - PEKK* |

Vat-polymerization SLA Vat-polymerization DLP Vat-polymerization CLIP Vat-polymerization LCD Material Jetting Powder-based Fusion SLS Material Extrusion FDM |

Casts, casted metal frameworks, pressed lithium disilicate wax restorations, surgical diagnosis, surgical guides, occlusal devices, deprogrammers, silicone indices, custom trays, interim restorations, denture teeth, mock-up restorations, denture bases, bone analogs, orthodontic aligners. |

|

Metal-based - Co-Cr Alloys - Titanium - Gold |

Powder-based Fusion SLS Powder-based Fusion SLM Powder-based Fusion EBM |

Surgical guides, splinting frameworks for complete arch impression techniques, frameworks for removable partial dentures, frameworks for tooth- and implant-supported prostheses, crowns, dental implants, and maxillofacial prosthetic parts. |

|

Ceramic-based - Zirconia* - Lithium Disilicate* - Hybrid Ceramics* |

Vat-polymerization SLA Vat-polymerization DLP Material Jetting Material Extrusion FDM Powder-based Fusion SLS |

Tooth-supported Restorations |

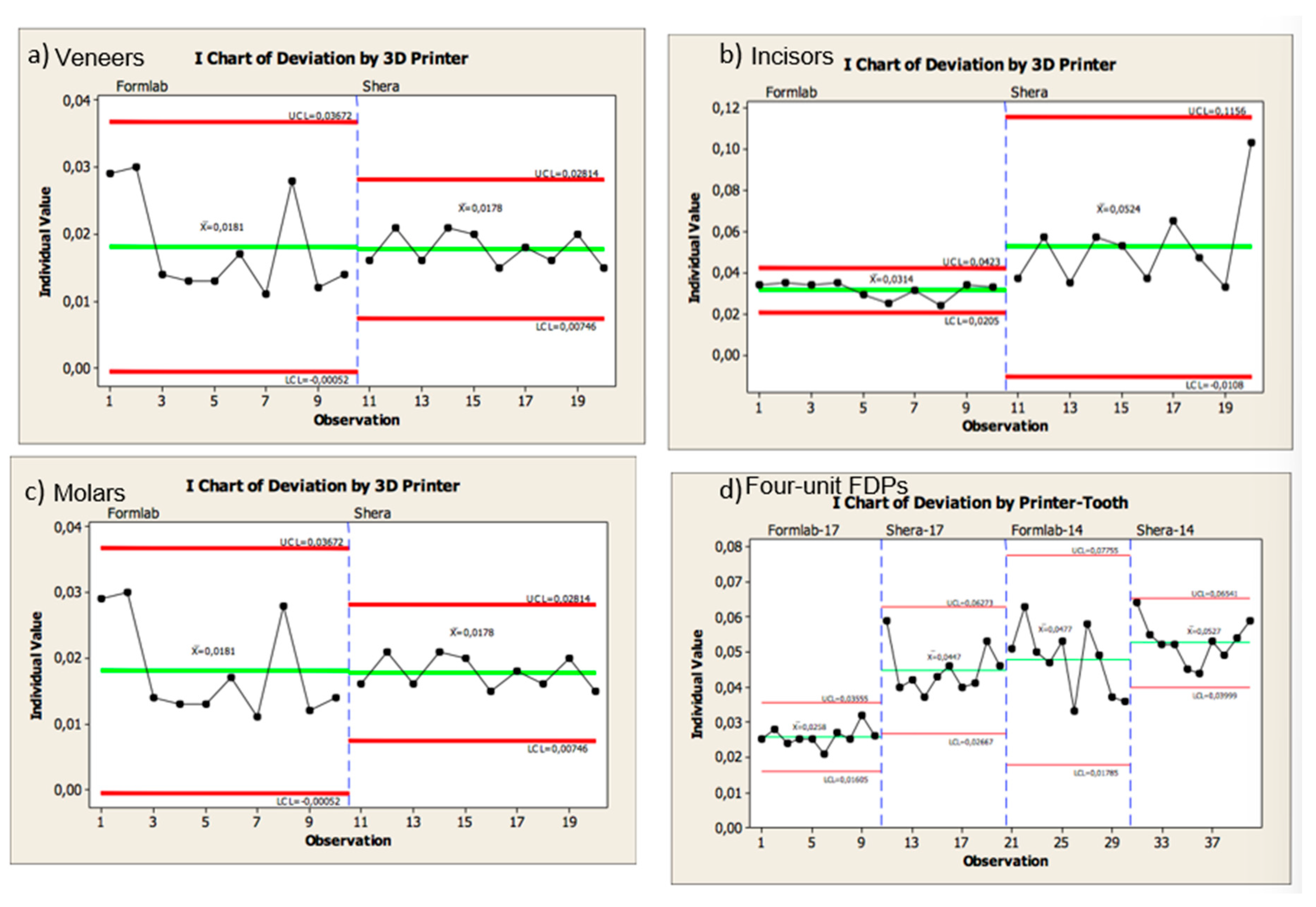

| Trueness | |||

| Volumetric Changes | P-Value |

Formlabs (Castable) |

Shera (Provisional) |

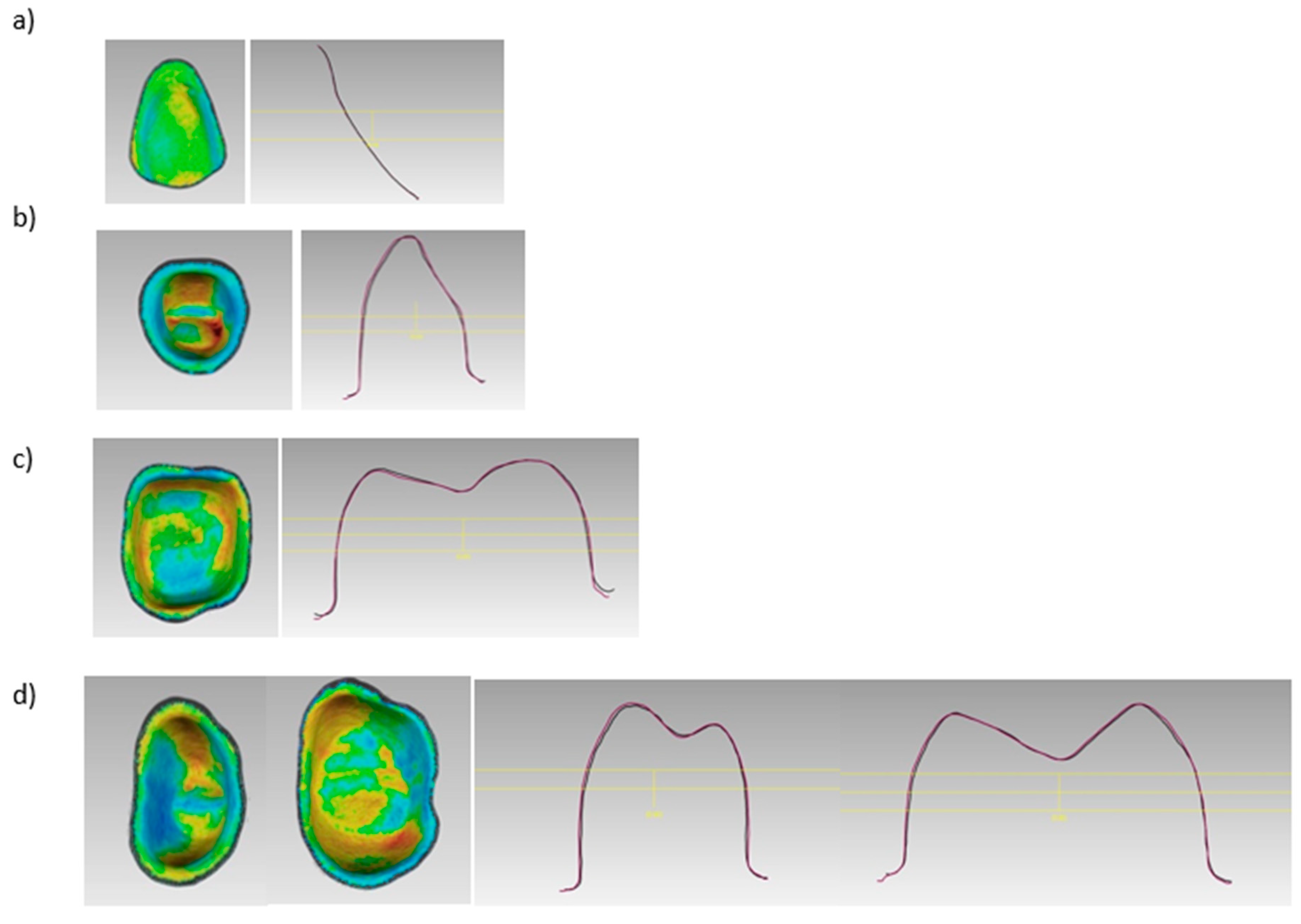

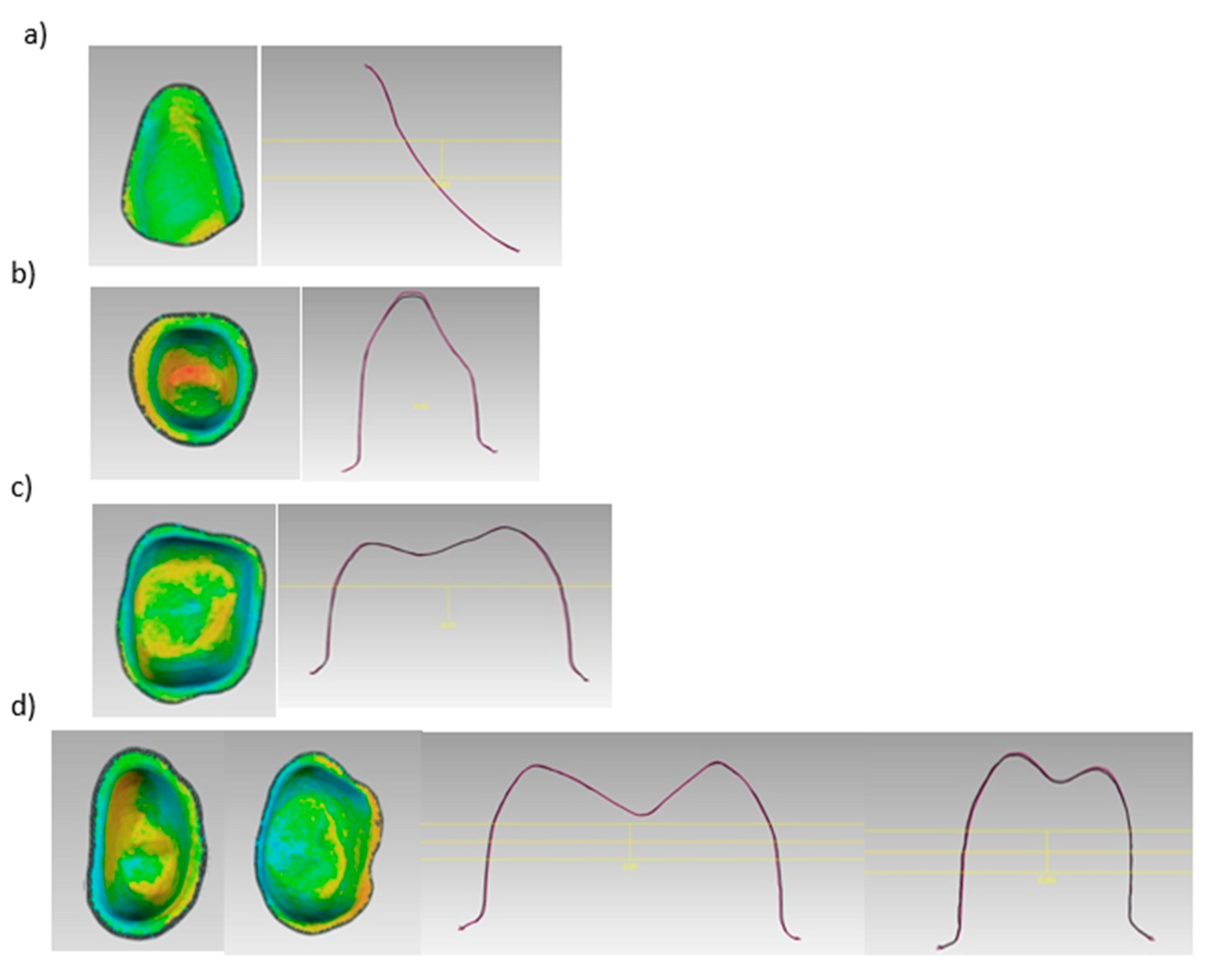

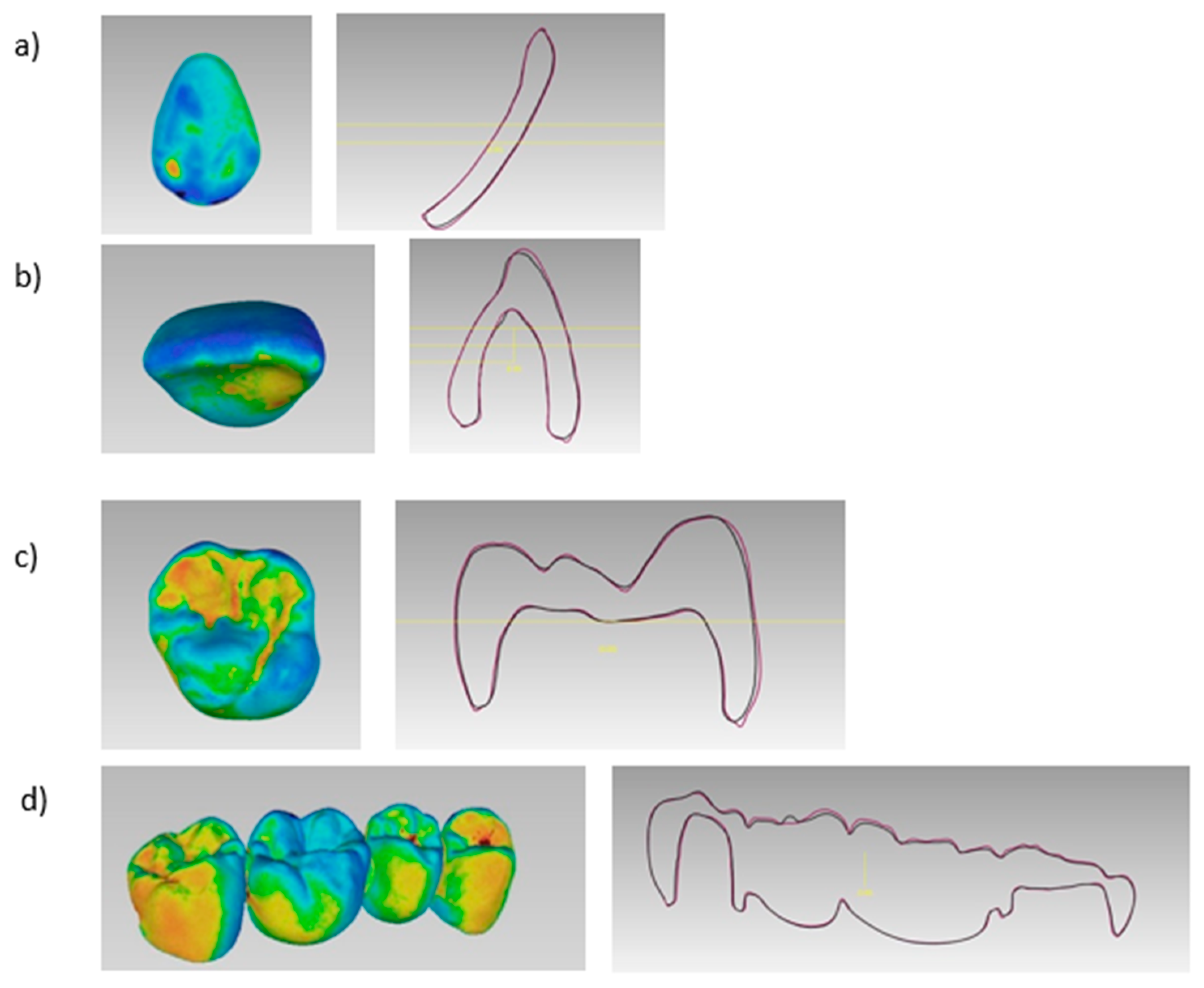

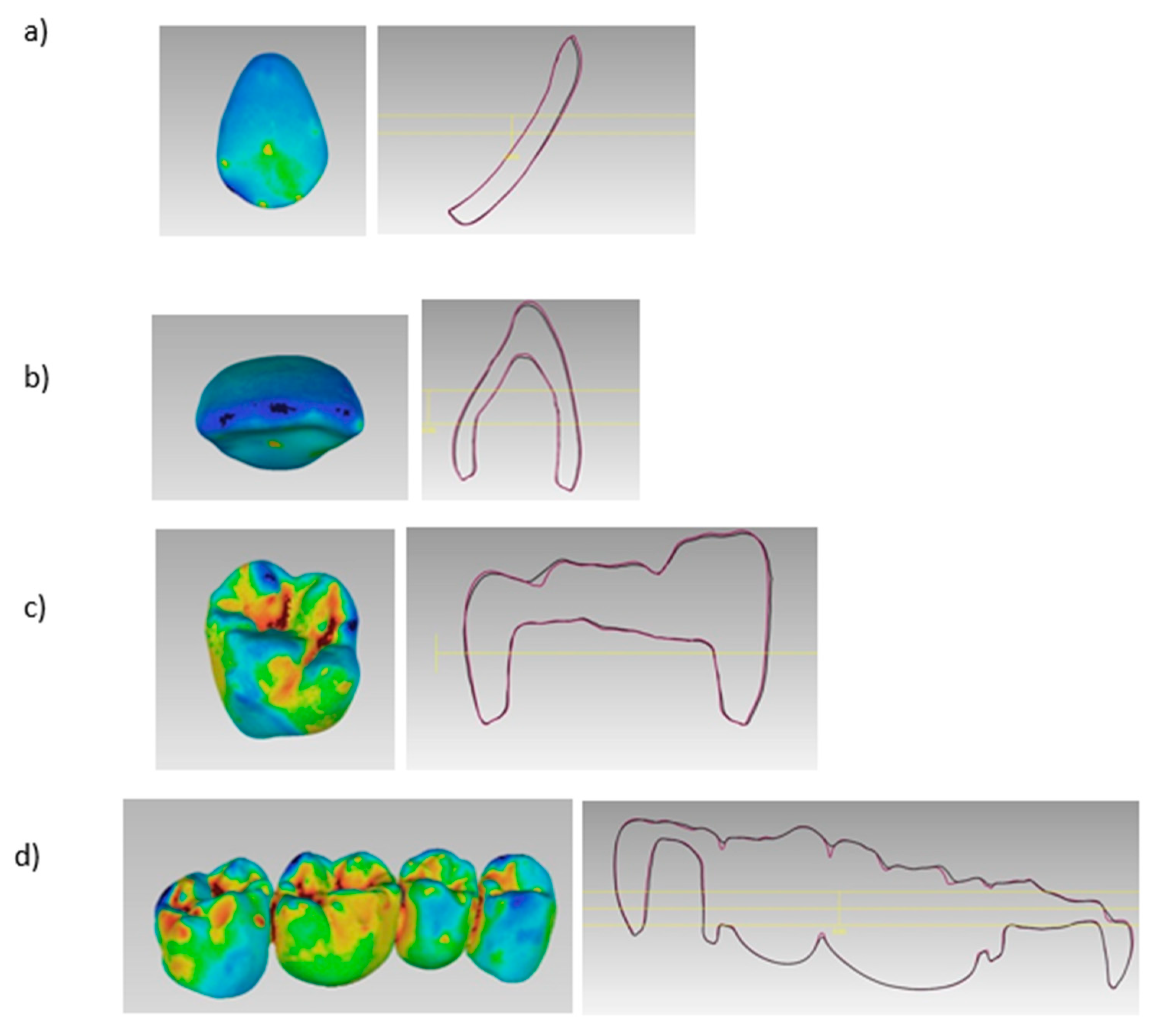

| Veneers | 0.854 | 88 ± 26 µm | 85 ± 41 µm |

| Incisors Labial | 0.001 | -97 ± 84 µm | -77 ± 98 µm |

| Incisors Palatal | 22 ± 83 µm | 64 ± 91 µm | |

| Molars | 0.002 | 53 ± 19 µm | 77 ± 42 µm |

| FPDs | 0.004 | 181 ± 91 µm | 214 ± 89 µm |

| Copings | p-Value |

Formlabs (castable) |

Shera (provisional) |

| Veneers | 0.909 | 18 ±7 µm | 17 ± 2 µm |

| Incisors | 0.012 | 31 ± 4 µm | 52 ± 20 µm |

| Molars | 0.001 | 23 ± 2 µm | 31 ± 4 µm |

| FPDs # 14 |

0.001 |

47 ± 9 µm | 52 ± 6 µm |

| FPDs # 17 | 25 ± 2 µm | 44 ± 6 µm | |

| Precision | |||

| External dimensional changes | p-Value |

Formlabs (LCL–UCL)* (castable) |

Shera (LCL-UCL)* (provisional) |

| Veneers | 0.054 | -3- 179 µm | -26- 198 µm |

| Incisors labial |

0.892 |

59- 139 µm | 69- 160 µm |

| Incisors palatal | 59- 137 µm | 64- 149 µm | |

| Molars | ≦ 0.001 | 2- 103 µm | -32- 188 µm |

| FPDs | 0.101 | 169 – 270 µm | 206 – 328 µm |

| Internal dimensional changes | p-Value |

Formlabs (LCL–UCL)* (castable) |

Shera (LCL-UCL)* (provisional) |

| Veneers | 0.002 | 0.5 – 36 µm | 7 – 28 µm |

| Incisors | ≦ 0.001 | 2 – 4 µm | 1 – 11 µm |

| Molars | 0.305 | 1 -5 µm | 2- 8 µm |

| FDPs # 14 |

0.012 |

6 – 12 µm | 3 – 13 µm |

| FDPs # 17 | 1 – 6 µm | 4 – 14 µm | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).