Submitted:

23 February 2024

Posted:

26 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

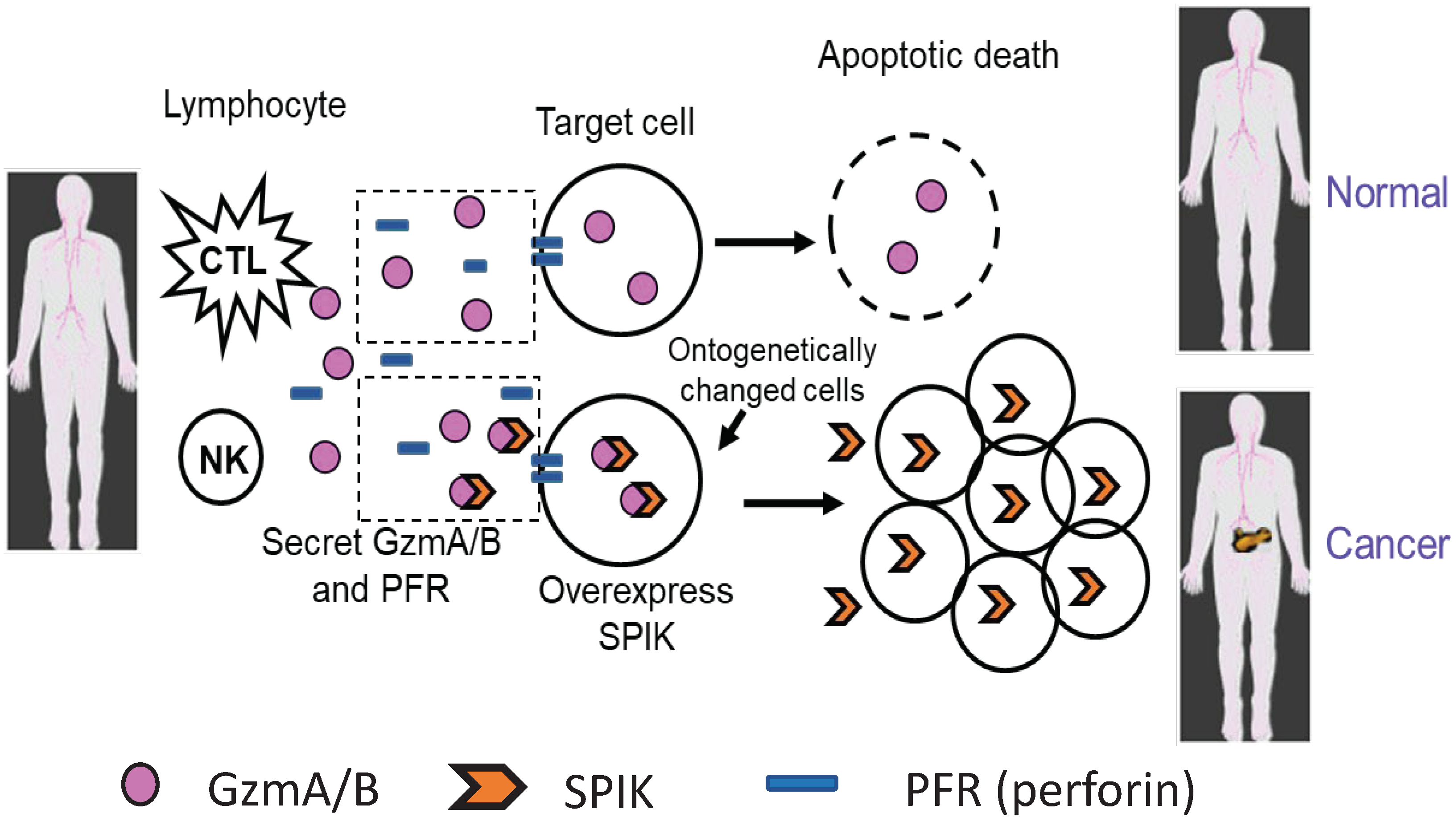

2. SPIK and the development of cancer

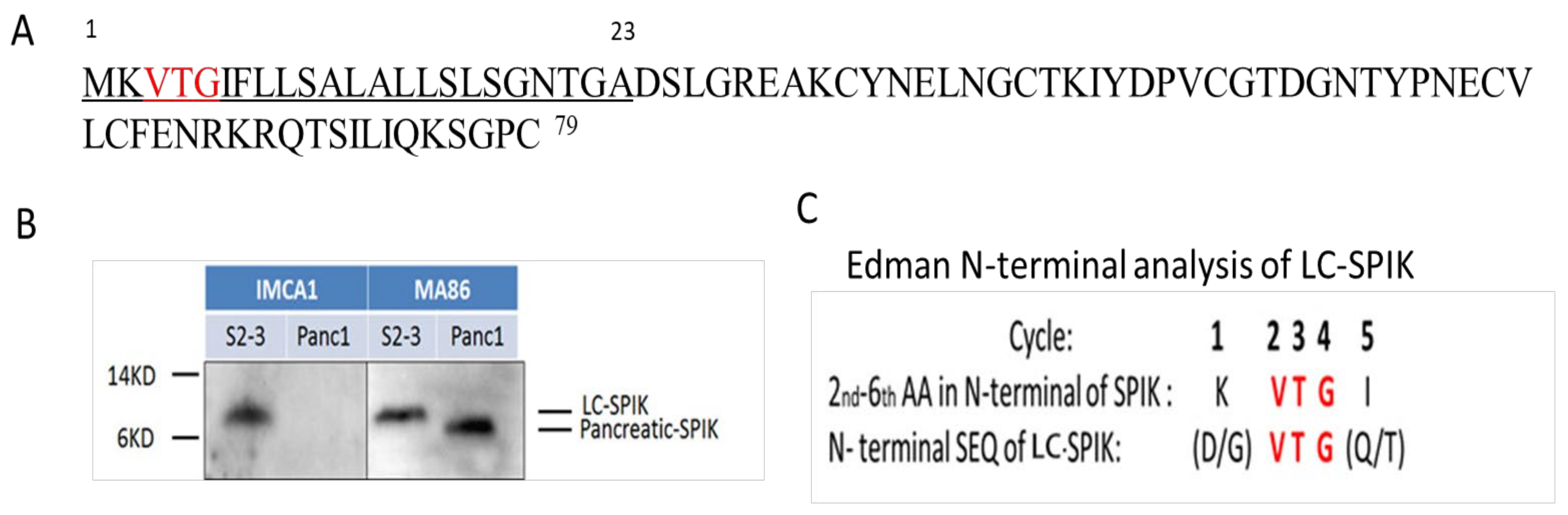

3. The difference between LC-SPIK and normal SPIK

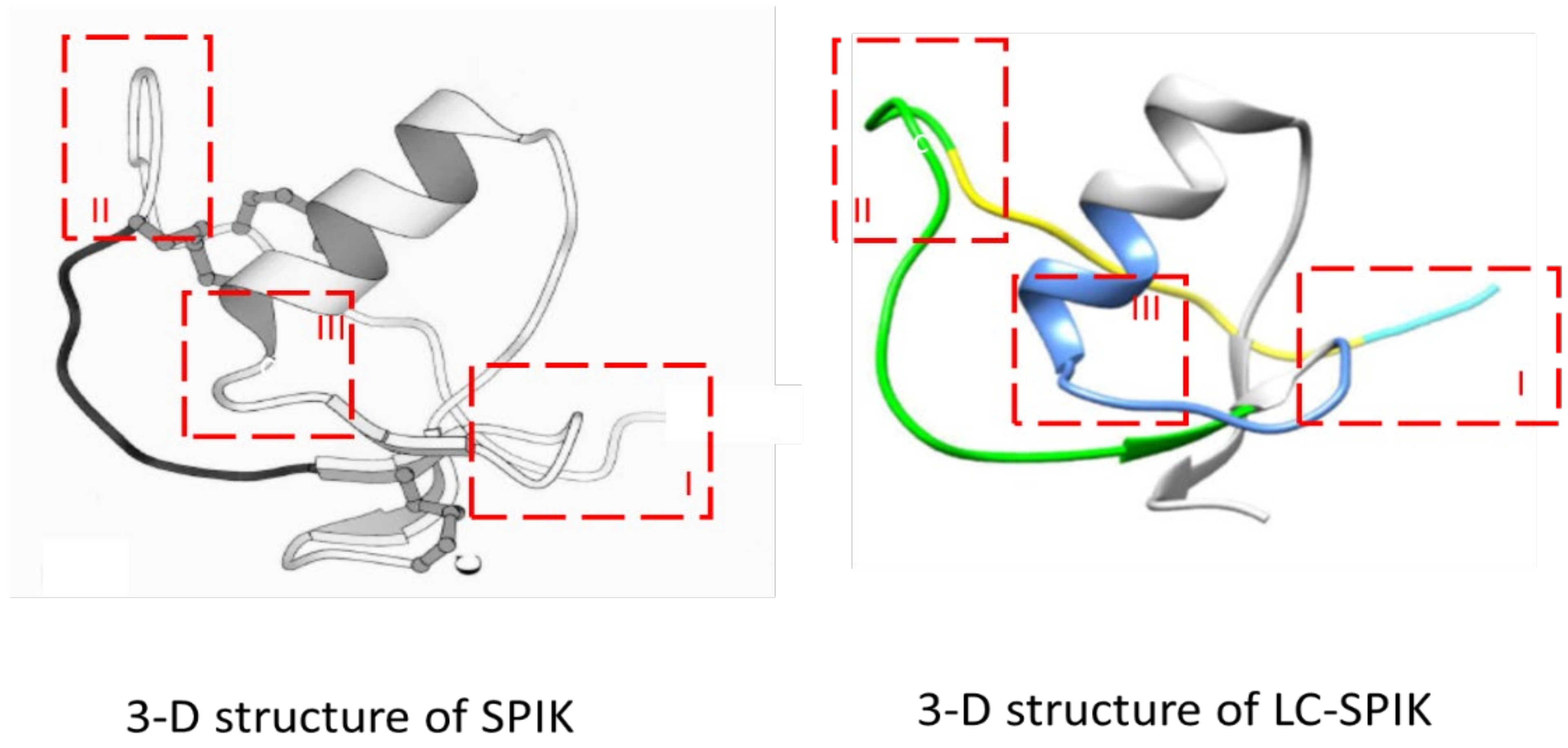

4. 3-D structure of LC-SPIK

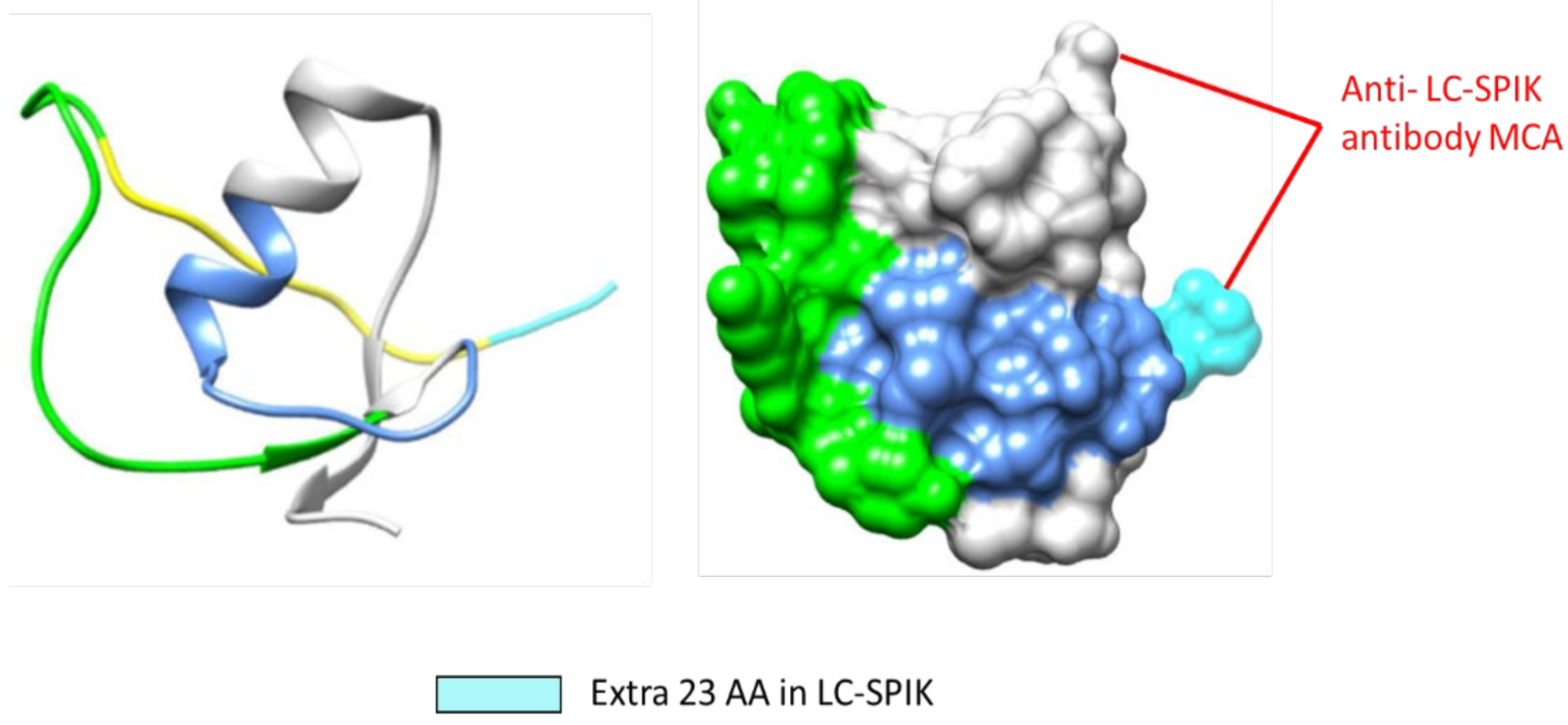

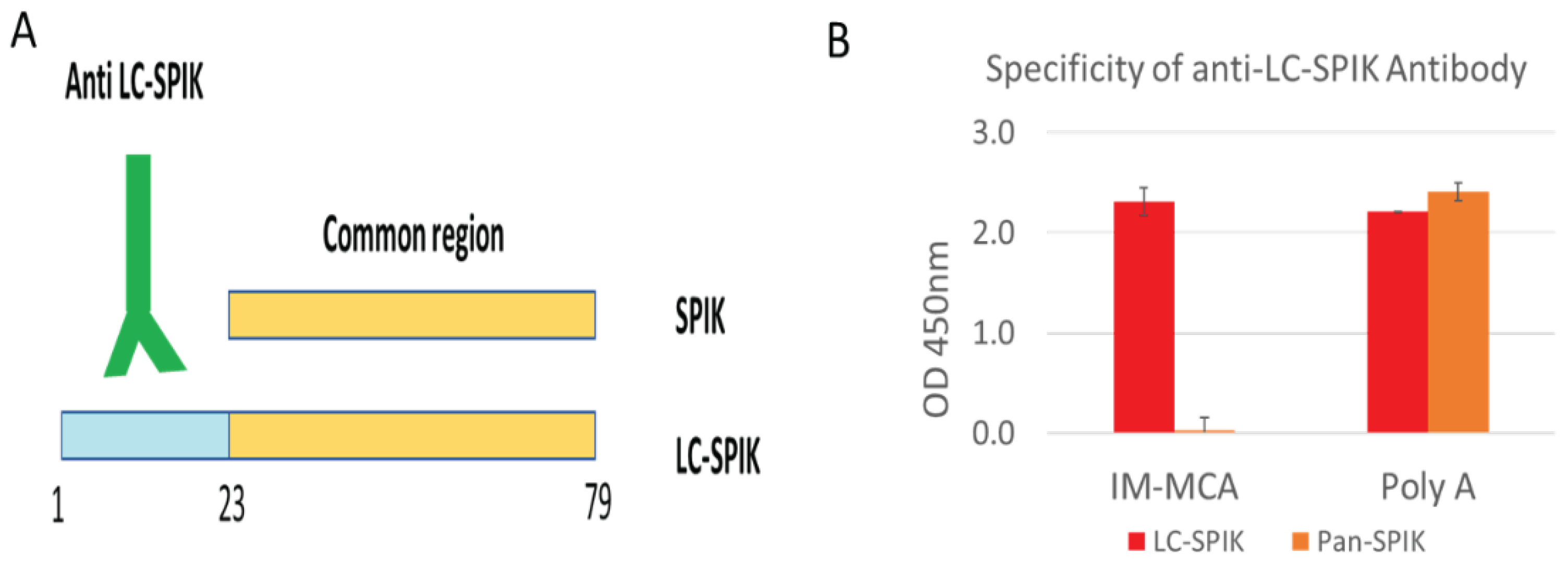

4. Development of anti-LC-SPIK antibody and test kit

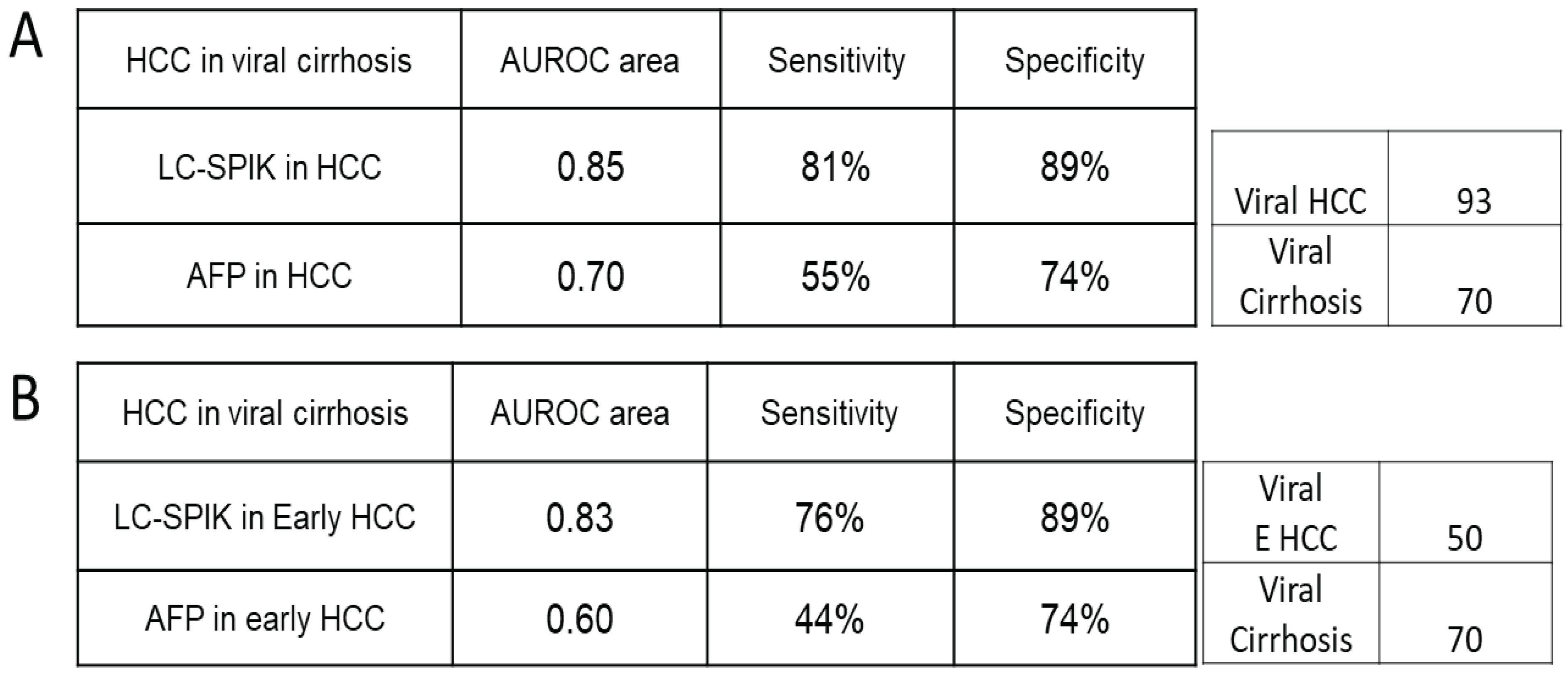

5. LC-SPIK and AFP expression in serum of patients with HCC.

6. Rise of non-viral risk factors for HCC.

7. LC-SPIK and AFP performance in detecting HCC due to non-viral cirrhosis.

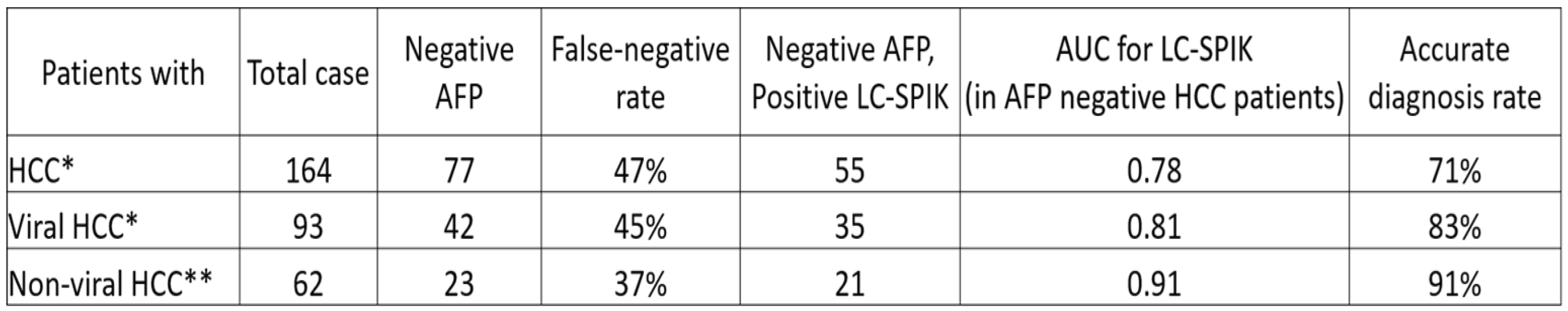

8. Detection of HCC in patients with false-negative AFP test results.

9. Combination of LC-SPIK test with other biomarkers in diagnosis of HCC.

10. Summary.

Author Contributions

Financial support

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest Statement

References

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer 2001;94:153-156. [CrossRef]

- Ricke J, Malfertheiner P. Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) contributes in a significant way to the worldwide burden of neoplastic diseases.. Preface. Dig Dis 2009;27:79. [CrossRef]

- Shiels MS, Engels EA, Yanik EL, McGlynn KA, Pfeiffer RM, O'Brien TR. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma among older Americans attributable to hepatitis C and hepatitis B: 2001 through 2013. Cancer 2019;125:2621-2630. [CrossRef]

- Ramani A, Tapper EB, Griffin C, Shankar N, Parikh ND, Asrani SK. Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Related Mortality in the USA, 1999-2018. Dig Dis Sci 2022;67:4100-4111. [CrossRef]

- Weiyi Wang, Wei C. Advances in the early diagnosis ofhepatocellular carcinoma. Genes & Diseases 2020;Available online.

- Brozzetti S, Bezzi M, De Sanctis GM, Andreoli GM, De Angelis M, Miccini M, Galati F, et al. Elderly and very elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Strategy for a first line treatment. Ann Ital Chir 2013;84.

- Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-1022. [CrossRef]

- Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, et al. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;68:723-750. [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69:182-236. [CrossRef]

- Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:589-604. [CrossRef]

- Nabihah Tayob FK, Abeer Alsarraj, Ruben Hernaez, Hashem B El-Serag. The Performance of AFP, AFP-3, DCP as Biomarkers for Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): A Phase 3 Biomarker Study in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;21:415-423. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Liu Y, Chen J, Shu H, Shen S, Li Y, Lu X, et al. Autoantibody signature in hepatocellular carcinoma using seromics. J Hematol Oncol 2020;13:85. [CrossRef]

- Gerstenmaier JF, Gibson RN. Ultrasound in chronic liver disease. Insights Imaging 2014;5:441-455. [CrossRef]

- Song P, Tang Q, Feng X, Tang W. Biomarkers: evaluation of clinical utility in surveillance and early diagnosis for hepatocellular carcinoma. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl 2016;245:S70-76. [CrossRef]

- Witjes CD, van Aalten SM, Steyerberg EW, Borsboom GJ, de Man RA, Verhoef C, Ijzermans JN. Recently introduced biomarkers for screening of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol Int 2013;7:59-64. [CrossRef]

- Giannini EG, Marenco S, Borgonovo G, Savarino V, Farinati F, Del Poggio P, Rapaccini GL, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein has no prognostic role in small hepatocellular carcinoma identified during surveillance in compensated cirrhosis. Hepatology 2012;56:1371-1379. [CrossRef]

- Aoyagi Y, Suzuki Y, Isemura M, Nomoto M, Sekine C, Igarashi K, Ichida F. The fucosylation index of alpha-fetoprotein and its usefulness in the early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 1988;61:769-774. [CrossRef]

- Malaguarnera G, Giordano M, Paladina I, Berretta M, Cappellani A, Malaguarnera M. Serum Markers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2010;55:2744-2755. [CrossRef]

- Sherman M. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors, and screening. Seminars in Liver Disease 2005;25:143-154.

- El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. alpha-Fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: mend it but do not end it. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:441-443. [CrossRef]

- Bartelt DC, Shapanka R, Greene LJ. The primary structure of the human pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor. Amino acid sequence of the reduced S-aminoethylated protein. Arch Biochem Biophys 1977;179:189-199. [CrossRef]

- Greene LJ, Pubols MH, Bartelt DC. Human pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor. Methods Enzymol 1976;45:813-825. [CrossRef]

- Marshall A, Lukk M, Kutter C, Davies S, Alexander G, Odom DT. Global gene expression profiling reveals SPINK1 as a potential hepatocellular carcinoma marker. PLoS One 2013;8:e59459. [CrossRef]

- Tonouchi A, Ohtsuka M, Ito H, Kimura F, Shimizu H, Kato M, Nimura Y, et al. Relationship between pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor and early recurrence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma following surgical resection. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1601-1610. [CrossRef]

- Lee YC, Pan HW, Peng SY, Lai PL, Kuo WS, Ou YH, Hsu HC. Overexpression of tumour-associated trypsin inhibitor (TATI) enhances tumour growth and is associated with portal vein invasion, early recurrence and a stage-independent prognostic factor of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2007;43:736-744. [CrossRef]

- Lu F, Lamontagne J, Sun A, Pinkerton M, Block T, Lu X. Role of the inflammatory protein serine protease inhibitor Kazal in preventing cytolytic granule granzyme A-mediated apoptosis. Immunology 2011;134:398-408. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Lee M, Tran T, Block T. High level expression of apoptosis inhibitor in hepatoma cell line expressing Hepatitis B virus. Int J Med Sci 2005;2:30-35. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Block T. Study of the early steps of the Hepatitis B Virus life cycle. Int J Med Sci 2004;1:21-33. [CrossRef]

- Ohmachi Y, Murata A, Matsuura N, Yasuda T, Yasuda T, Monden M, Mori T, et al. Specific expression of the pancreatic-secretory-trypsin-inhibitor (PSTI) gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer 1993;55:728-734. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa M, Shibata T, Niinobu T, Uda K, Takata N, Mori T. Serum pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI) in patients with inflammatory diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol 1988;240:505-508. [CrossRef]

- Witt H, Luck W, Hennies HC, Classen M, Kage A, Lass U, Landt O, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the serine protease inhibitor, Kazal type 1 are associated with chronic pancreatitis. Nat Genet 2000;25:213-216. [CrossRef]

- Cavestro GM, Zuppardo RA, Bertolini S, Sereni G, Frulloni L, Okolicsanyi S, Calzolari C, et al. Connections between genetics and clinical data: Role of MCP-1, CFTR, and SPINK-1 in the setting of acute, acute recurrent, and chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:199-206. [CrossRef]

- Uda K, Murata A, Nishijima J, Doi S, Tomita N, Ogawa M, Mori T. Elevation of circulating monitor peptide/pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor-I (PSTI-61) after turpentine-induced inflammation in rats: hepatocytes produce it as an acute phase reactant. J Surg Res 1994;57:563-568. [CrossRef]

- Zhu WW, Guo JJ, Guo L, Jia HL, Zhu M, Zhang JB, Loffredo CA, et al. Evaluation of midkine as a diagnostic serum biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:3944-3954. [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne J, Pinkerton M, Block TM, Lu X. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus replication upregulates serine protease inhibitor Kazal, resulting in cellular resistance to serine protease-dependent apoptosis. J Virol 2010;84:907-917. [CrossRef]

- Wiksten JP, Lundin J, Nordling S, Kokkola A, Stenman UH, Haglund C. High tissue expression of tumour-associated trypsin inhibitor (TATI) associates with a more favourable prognosis in gastric cancer. Histopathology 2005;46:380-388. [CrossRef]

- Gaber A, Nodin B, Hotakainen K, Nilsson E, Stenman UH, Bjartell A, Birgisson H, et al. Increased serum levels of tumour-associated trypsin inhibitor independently predict a poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2010;10:498. [CrossRef]

- Chisari FV. Cytotoxic T cells and viral hepatitis. J Clin Invest 1997;99:1472-1477. [CrossRef]

- Chisari FV, Isogawa M, Wieland SF. Pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus infection. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2010;58:258-266. [CrossRef]

- Guicciardi ME, Malhi H, Mott JL, Gores GJ. Apoptosis and necrosis in the liver. Compr Physiol 2013;3:977-1010. [CrossRef]

- Kerr JF, Winterford CM, Harmon BV. Apoptosis. Its significance in cancer and cancer therapy. Cancer 1994;73:2013-2026. [CrossRef]

- Pardo J, Balkow S, Anel A, Simon MM. Granzymes are essential for natural killer cell-mediated and perf-facilitated tumor control. Eur J Immunol 2002;32:2881-2887. [CrossRef]

- Pardo J, Aguilo JI, Anel A, Martin P, Joeckel L, Borner C, Wallich R, et al. The biology of cytotoxic cell granule exocytosis pathway: granzymes have evolved to induce cell death and inflammation. Microbes Infect 2009;11:452-459. [CrossRef]

- Räsänen K, Itkonen O, Koistinen H, Stenman UH. Emerging Roles of SPINK1 in Cancer. Clin Chem 2016;62:449-457. [CrossRef]

- Tsuzuki S, Kokado Y, Satomi S, Yamasaki Y, Hirayasu H, Iwanaga T, Fushiki T. Purification and identification of a binding protein for pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor: a novel role of the inhibitor as an anti-granzyme A. Biochem J 2003;372:227-233. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman J. Granzyme A activates another way to die. Immunological Reviews 2010;235:93-104. [CrossRef]

- Soon WW, Miller LD, Black MA, Dalmasso C, Chan XB, Pang B, Ong CW, et al. Combined genomic and phenotype screening reveals secretory factor SPINK1 as an invasion and survival factor associated with patient prognosis in breast cancer. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2011;3:451-464. [CrossRef]

- T M, G W, M N-H, RJ. P. Pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor is amajormotogenic and protective factor in human breast milk. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2009;296:G697–703. [CrossRef]

- Frisch S, Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. Journal of Cell Biology 1994;124:619-626. [CrossRef]

- Bladergroen BA, Meijer CJLM, ten Berge RL, Hack CE, Muris JJF, Dukers DF, Chott A, et al. Expression of the granzyme B inhibitor, protease inhibitor 9, by tumor cells in patients with non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma: a novel protective mechanism for tumor cells to circumvent the immune system? Blood 2002;99:232-237. [CrossRef]

- Suminami Y, Nagashima S, Vujanovic NL, Hirabayashi K, Kato H, Whiteside TL. Inhibition of apoptosis in human tumour cells by the tumour-associated serpin, SCC antigen-1. Br J Cancer 2000;82:981-989. [CrossRef]

- Itkonen O, Stenman UH. TATI as a biomarker. Clin Chim Acta 2014;431:260-269. [CrossRef]

- Hirota M, Ohmuraya M, Baba H. The role of trypsin, trypsin inhibitor, and trypsin receptor in the onset and aggravation of pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol 2006;41:832-836. [CrossRef]

- Playford RJ, Hanby AM, Quinn C, Calam J. Influence of inflammation and atrophy on pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor levels within the gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology 1994;106:735-741. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi K, Horiuchi M, Saheki T. Pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor as a diagnostic marker for adult-onset type II citrullinemia. Hepatology 1997;25:1160-1165. [CrossRef]

- Hecht HJ, Szardenings M, Collins J, Schomburg D. Three-dimensional structure of a recombinant variant of human pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (Kazal type). J Mol Biol 1992;225:1095-1103. [CrossRef]

- Graf R, Bimmler D. Biochemistry and biology of SPINK-PSTI and monitor peptide. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2006;35:333-343, ix. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Lamontagne J, Lu F, Block T. Tumor-associated protein SPIK/TATI suppresses serine protease dependent cell apoptosis. Apoptosis 2008;13:483-494. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi N, Nagata K, Yoshida N, Tanaka T, Yamamoto M, Saitoh Y. Purification and complete amino acid sequence of canine pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor. FEBS Letters 1985;191:269-272. [CrossRef]

- Abhishek Rao; Felix Lu, Jason Lamontagne and Xuanyong Lu. A New Biomarker for Early Detection of HCC and ICC. Hepatology International 2013;7 (suppl II):S554.

- Lu F, Shah PA, Rao A, Gifford-Hollingsworth C, Chen A, Trey G, Soryal M, et al. Liver Cancer–Specific Serine Protease Inhibitor Kazal Is a Potentially Novel Biomarker for the Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 2020;11:e00271. [CrossRef]

- Harris PS, Hansen RM, Gray ME, Massoud OI, McGuire BM, Shoreibah MG. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: An evidence-based approach. World J Gastroenterol 2019;25:1550-1559. [CrossRef]

- Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology 2004;127:S35-50. [CrossRef]

- Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, Shoham D, Durazo R, Luke A, Volk ML. The Epidemiology of Cirrhosis in the United States: A Population-based Study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015;49:690-696. [CrossRef]

- Tokushige K, Ikejima K, Ono M, Eguchi Y, Kamada Y, Itoh Y, Akuta N, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis 2020. J Gastroenterol 2021;56:951-963. [CrossRef]

- Simmons O, Fetzer DT, Yokoo T, Marrero JA, Yopp A, Kono Y, Parikh ND, et al. Predictors of adequate ultrasound quality for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:169-177. [CrossRef]

- Della Corte C, Colombo M. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol 2012;39:384-398. [CrossRef]

- Danila M, Sporea I. Ultrasound screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with advanced liver fibrosis. An overview. Med Ultrason 2014;16:139-144. [CrossRef]

- Singal A, Volk ML, Waljee A, Salgia R, Higgins P, Rogers MA, Marrero JA. Meta-analysis: surveillance with ultrasound for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:37-47. [CrossRef]

- Loomba R, Lim JK, Patton H, El-Serag HB. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Screening and Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2020;158:1822-1830. [CrossRef]

- Caviglia GP, Nicolosi A, Abate ML, Carucci P, Rosso C, Rolle E, Armandi A, et al. Liver Cancer-Specific Isoform of Serine Protease Inhibitor Kazal for the Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Results from a Pilot Study in Patients with Dysmetabolic Liver Disease. Curr Oncol 2022;29:5457-5465. [CrossRef]

- Malaguarnera G, Giordano M, Paladina I, Berretta M, Cappellani A, Malaguarnera M. Serum markers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:2744-2755. [CrossRef]

- Mehta N, Kotwani P, Norman J, Shui A, Li PY, Saxena V, Chan W, et al. AFP-L3 and DCP are superior to AFP in predicting waitlist dropout in HCC patients: Results of a prospective study. Liver Transpl 2023. [CrossRef]

- Best J, Bilgi H, Heider D, Schotten C, Manka P, Bedreli S, Gorray M, et al. The GALAD scoring algorithm based on AFP, AFP-L3, and DCP significantly improves detection of BCLC early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Z Gastroenterol 2016;54:1296-1305. [CrossRef]

- Liu XN CD, Li YF, Liu YH, Liu G, Liu L. Multiple "Omics" data-based biomarker screening for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4199-4212. [CrossRef]

| Marker | AUC Alone | LC-SPIK+AFP | LC-SPIK+PIVKA-II | LC-SPIK+AFP+PIVKA-II | |||

| AUC | AUC increase | AUC | AUC increase | AUC | AUC increase | ||

| LC-SPIK | 0.841 | 0.897 | 0.056 | 0.926 | 0.085 | 0.932 | 0.091 |

| AFP | 0.719 | 0.178 | X | 0.213 | |||

| PIVKA-II | 0.853 | X | 0.073 | 0.079 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).