Submitted:

23 February 2024

Posted:

26 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Patients and ECP

Sample collection

Flow cytometric analysis

Statistical analyses

Results

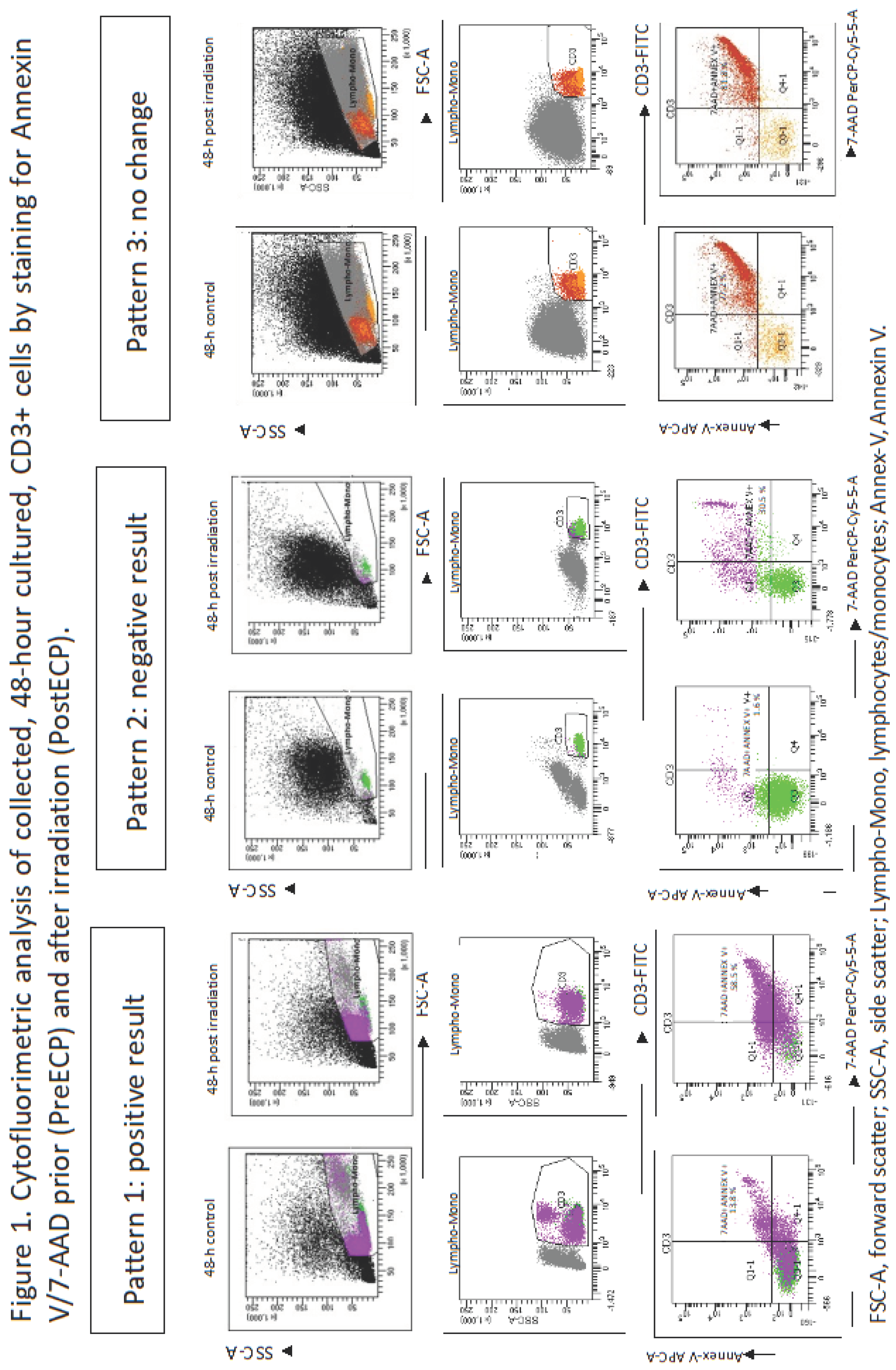

) on CD3+ cells, prior and after irradiation; Table 1) at the time of first ECP procedure. We observed a parallel increase in Annexin V and 7-AAD fluorescence even though, in 4 cases out of 21, positivity for Annexin V paralleled a border-line 7-AAD staining (increase of 7-AAD staining was around 40 %). In eight cases we observed 3 “negative result” and 5 “no change”. Table 1 shows that lymphocyte count/μL in collected buffy coat was extremely variable, ranging from 360 to 23,100. We didn’t find a significant correlation between the lymphocyte count in the buffy coat and a “positive result” of Annexin V/7-AADΔ (R2=0.027; p= 0.393). No correlations were found between age, gender, disease, aGVHD grade and time from transplant to first ECP and Annexin V/7-AAD Δ (p>0.05 in all cases). We built a score, ranging from 0 to 2 (see methods), which combines survival on aGVHD and the number of ECP procedures performed in each patient (< 21 procedures, > 21 procedures); this score was challenged at linear regression analysis with a “positive result” for Annexin V/7-AADΔ and we found a weak, albeit significant, correlation (R= 0.395; p=0.033). This score correlated neither with lymphocyte count in the buffy coat, nor with gender , disease, age, aGVHD grade and the number of days between transplant and the first ECP. To ascertain the influence of possible confounding effects, we performed a multiple regression analysis between score and Annexin V/7-AAD lymphocyte count in the buffy coat, gender, disease, age, aGVHD grade and the number of days from transplant to the first ECP. By this additional analysis Annexin V/7-AADΔ maintained its statistical significance (Coefficient 0.952, p=0.004; Table 2).

) on CD3+ cells, prior and after irradiation; Table 1) at the time of first ECP procedure. We observed a parallel increase in Annexin V and 7-AAD fluorescence even though, in 4 cases out of 21, positivity for Annexin V paralleled a border-line 7-AAD staining (increase of 7-AAD staining was around 40 %). In eight cases we observed 3 “negative result” and 5 “no change”. Table 1 shows that lymphocyte count/μL in collected buffy coat was extremely variable, ranging from 360 to 23,100. We didn’t find a significant correlation between the lymphocyte count in the buffy coat and a “positive result” of Annexin V/7-AADΔ (R2=0.027; p= 0.393). No correlations were found between age, gender, disease, aGVHD grade and time from transplant to first ECP and Annexin V/7-AAD Δ (p>0.05 in all cases). We built a score, ranging from 0 to 2 (see methods), which combines survival on aGVHD and the number of ECP procedures performed in each patient (< 21 procedures, > 21 procedures); this score was challenged at linear regression analysis with a “positive result” for Annexin V/7-AADΔ and we found a weak, albeit significant, correlation (R= 0.395; p=0.033). This score correlated neither with lymphocyte count in the buffy coat, nor with gender , disease, age, aGVHD grade and the number of days between transplant and the first ECP. To ascertain the influence of possible confounding effects, we performed a multiple regression analysis between score and Annexin V/7-AAD lymphocyte count in the buffy coat, gender, disease, age, aGVHD grade and the number of days from transplant to the first ECP. By this additional analysis Annexin V/7-AADΔ maintained its statistical significance (Coefficient 0.952, p=0.004; Table 2). | |

Age at ECP (years) | Gender | Disease | Days from transplant to 1st ECP | aGVHD grade | aGVHD Treatment |

ECP procedures n° | CD3+ Ann V Δ>40%* | CD3+ 7AA-D Δ>40%* | Lymph count/μL in the BC at 1stECP |

A/D | Score ° |

| A. | 21 | F | HD | 45 | 3 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 19 | + | + | 360 | A | 2 |

| B. | 56 | F | MM | 70 | 3 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 22 | + | + | 680 | D | 0 |

| C. | 71 | M | NHL | 65 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 29 | + | + | 5,180 | A | 1 |

| D. | 8 | F | B-Tal | 40 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 30 | + | +/- | 2,000 | A | 1 |

| E. | 51 | M | AML | 45 | 3 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 21 | - | - | 1,900 | D | 0 |

| F. | 46 | M | AML | 80 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 67 | + | + | 23,100 | A | 1 |

| G. | 49 | F | AML | 64 | 3 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 42 | - | - | 15,000 | A | 1 |

| H. | 55 | M | NHL | 63 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 34 | + | + | 12,700 | A | 1 |

| I. | 63 | M | AML | 47 | 3 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 11 | + | + | 5,870 | A | 2 |

| J. | 29 | F | HD | 82 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 57 | - | - | 1,040 | A | 1 |

| K. | 27 | M | AML | 90 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 30 | + | + | 4,880 | A | 1 |

| L. | 48 | M | AML | 87 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 35 | + | + | 4,830 | A | 1 |

| M. | 34 | F | AML | 28 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 17 | - | - | 10,100 | A | 2 |

| N. | 46 | M | AML | 73 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 21 | - | - | 9,450 | D | 0 |

| O. | 54 | M | AML | 100 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 46 | + | + | 650 | D | 0 |

| P. | 63 | M | AML | 100 | 3 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 30 | + | +/- | 9,760 | A | 1 |

| Q. | 51 | F | AML | 90 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 14 | + | + | 10,000 | A | 2 |

| R. | 43 | M | AML | 44 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 10 | + | + | 6,750 | A | 2 |

| S. | 49 | M | NHL | 44 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 7 | + | +/- | 7,340 | A | 2 |

| T. | 44 | M | NHL | 99 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 9 | + | + | 8,460 | A | 2 |

| U. | 58 | F | NHL | 84 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 4 | - | - | 10,150 | D | 1 |

| V. | 21 | F | AML | 86 | 3 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 19 | + | + | 1,100 | A | 2 |

| W. | 40 | F | NHL | 91 | 3 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 12 | + | + | 6,500 | A | 2 |

| X. | 53 | F | NHL | 84 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 28 | - | - | 2,100 | D | 0 |

| Y. | 47 | M | AML | 43 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 15 | - | - | 11,340 | D | 1 |

| Z. | 38 | M | AML | 62 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 5 | + | + | 850 | A | 2 |

| AA. | 55 | M | NHL | 48 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 46 | + | +/- | 2,300 | A | 1 |

| BB. | 49 | F | MM | 94 | 3 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 27 | + | + | 6,200 | A | 1 |

| CC. | 53 | F | AML | 71 | 4 | MetPredn 2mg/kg | 18 | + | + | 490 | A | 2 |

| n° 29 | Median 49 ( 8-71) | M=16/F= 13 | AML=16 Others= 13 | Median 71 (28-100) |

Median 4 ( 3-4) |

Total= 725 Median 21 (4-67) |

Median 5,870 ( 360-23,100) |

A= 22 D= 7 |

Mean 1.20 Median 1 ( 0-2) |

| Coefficient | p | |

| Age | -0.006 | 0.504 |

| Disease | 0.264 | 0.334 |

| Gender | 0.523 | 0.114 |

| Days from transplant to ECP | -0.010 | 0.094 |

| aGVHD grade | 0.146 | 0.611 |

Lymph/ L in the buffy coat L in the buffy coat |

0.029 | 0.243 |

| Annexin V/7-AAD Δ* | 0.952 | 0.004 |

Discussion

- 1)

- the quality control by the evaluation of Annexin V/7-AAD Δ consents to ascertain the in vitro effect of ECP in most patients

- 2)

- few patients showed an unexpected result, with in vitro resistance to ECP action (lack of apoptosis/death induction or no change as compared to controls) which deserves further investigations

- 3)

- the lymphocyte behavior described for point 2) correlates with a worse outcome during ECP

Author contribution

References

- Greinix, H.T.; Eikema, D.-J.; Koster, L.; Penack, O.; Yakoub-Agha, I.; Montoto, S.; Chabannon, C.; Styczynski, J.; Nagler, A.; Robin, M.; et al. Improved outcome of patients with graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies over time: an EBMT mega-file study. Haematologica 2022, 107, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiser, R.; Blazar, B.R. Pathophysiology of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease and Therapeutic Targets. N Engl J Medn 2017, 377, 2565–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greinix, H.T.; Ayuk, F.; Zeiser, R. Extracorporeal photopheresis in acute and chronic steroid refractory graft-versus-host disease: an envolving treatment landscape. Leukemia 2022, 11, 2558–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Dalle, I.; Reljic, T.; Nishihori, T.; Antar, A.; Bazarbachi, A.; Djulbegovic, B.; Kumar, A.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A. Extracorporeal photopheresis in steroid-refractory acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease: results of a systematic review of prospective studies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014, 20, 1677–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierelli, L.; Perseghin, P.; Marchetti, M.; Messina, C.; Perotti, C.; Mazzoni, A.; Bacigalupo, A.; Locatelli, F.; Carlier, P.; Bosi, A. Società Italiana di Emaferesi and Manipolazione Cellulare (SIdEM); Gruppo Italiano Trapianto Midollo Osseo (GITMO). Extracorporeal photopheresis for the treatment of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease in adults and children: best practice recommendations from an Italian Society of Hemapheresis and Cell Manipulation (SIdEM) and Italian Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation (GITMO) consensus process. Transfusion 2013, 53, 2340–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygaard, M.; Wichert, S.; Berlin, G.; Toss, F. Extracorporeal photopheresis for graft-vs-host disease: A literature review and treatment guidelines proposed by the Nordic ECP Quality Group. Eur J Haematol 2020, 104, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieyra-Garcia, P.A.; Wolf, P. Extracorporeal Photopheresis: A Case of Immunotherapy Ahead of Its Time. Transfus Med Hemother 2020, 47, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taverna, F.; Coluccia, P.; Arienti, F.; Birolini, A.; Terranova, L.; Mazzocchi, A.; Rini, F.; Mariani, L.; Melani, C.; Ravagnani, F. Biological quality control for extracorporeal photochemotherapy: Assessing mononuclear cell apoptosis levels in ECP bags of chronic GvHD patients. J Clin Apher 2015, 30, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, A.; Tarbunova, M.; Despotis, G.; Grossman, BJ. The CELLEX is comparable to the UVAR-XTS for the treatment of acute and chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD). Transfusion 2020, 60, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worel, N.; Lehner, E.; Führer, H.; Kalhs, P.; Rabitsch, W.; Mitterbauer, M.; Hopfinger, G.; Greinix, HT. Extracorporeal photopheresis as second-line therapy for patients with acute graft-versus-host disease: does the number cells treated matter? Transfusion 2018, 58, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierelli, L.; Bosi, A.; Olivieri, A. "Best practice" for extracorporeal photopheresis in acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease by Societa' Italiana di Emaferesi and Manipolazione Cellulare and Gruppo Italiano Trapianto Midollo Osseo: a national survey to ascertain its degree of application in Italian transplant centers. Transfusion 2018, 58, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).