Submitted:

23 February 2024

Posted:

26 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Reference | Country | Plot | Area | Model | RS source$ | Regression | RMSE## | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ha | Aproach& | Model# | kg ha-1 | |||||

| [10] | China | 355 | - | CV/RS | Modis/Sentinel | LSTM, SVM, RF | 375 | 0.65 |

| [42] | EUA | 12 | 150 | CM/RS | Spectroradiometer | 468 | - | |

| [13] | USA | 3 | 188 | RS | Modis/Landsat | LR | 673 | 0.52 |

| [14] | USA | - | - | RS | Modis | LR | - | 0.16 |

| [11] | India | - | - | CV, RS | Modis | RF | 157 | 0.69 |

| [12] | Australia | 253 | - | CV, RS | Landsat | RF | 976 | - |

| [17] | USA | 1 | 5 | RS | UAV | MLR | 261 | 0.87 |

| [36] | USA | 805 | 0,65 | RS | UAV | ANN, RF | - | 0.72 |

| [39] | USA | 1 | 57 | RS | Modis/Landsat | 463 | 0.84 | |

| [43] | USA | - | - | EM/RS | Sentinel | - | - | |

| [18] | USA | 2550 | 6 | RS | UAV | LR | 550 | 0.92 |

| [37] | Brazil | 1 | 90 | RS | Optical sensor | decision trees | - | 0.81 |

| [40] | USA | - | 73 | RS | Landsat | ANN | 375-470 | 0.71 |

| [38] | USA | 2 | 120 | RS | Landsat | exponential | 481 | 0.81 |

| [19] | Australia | 90 | 7 | RS | UAV | LR and quadradic | - | 0.75 |

| [15] | USA | 949 | - | RS | Modis | LR | - | 0.48 |

| [16] | USA | 24 | 0,2 | RS | NASA data | LR | - | 0.85 |

| [21] | USA | 48 | 1,5 | RS | Airborne | LR | - | 0.47 |

| [22] | USA | 44 | 5,3 | RS | Spectroradiometer | LR | - | 0.89 |

| &CV: Climate Variables, RS: Remote Sensing, CM: Crop Model, EM: Ecosystem Model; %RS: Remote Sensing; | ||||||||

| UAV: Unmanned Aerial Vehicle; #LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory; SVM: Support Vector Machine; RF: Random Forest; | ||||||||

| LR: Linear Regression, MLR: Multiple Linear Regression, ANN: Artificial Neural, Network; | ||||||||

| ##Root Mean Square Error of seed cotton yield. | ||||||||

2. Materials and Methods

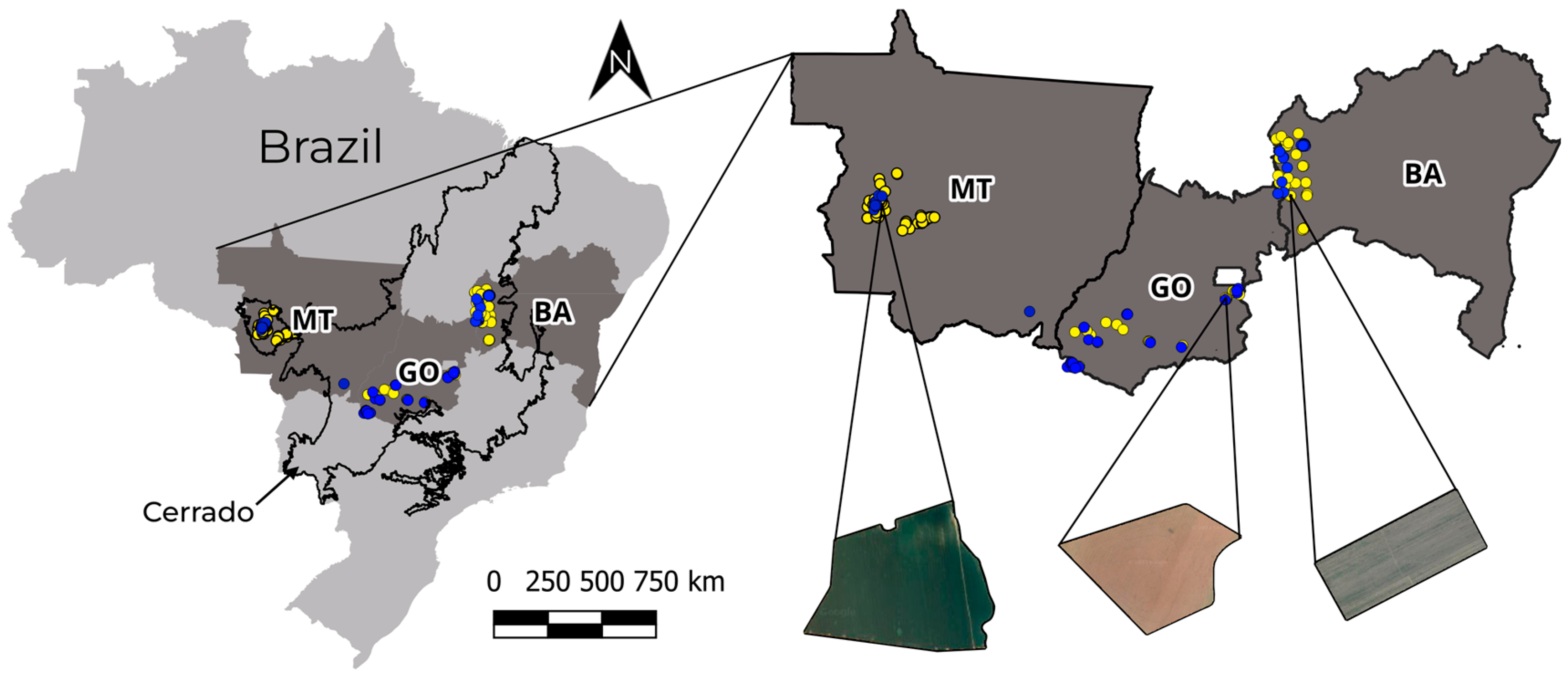

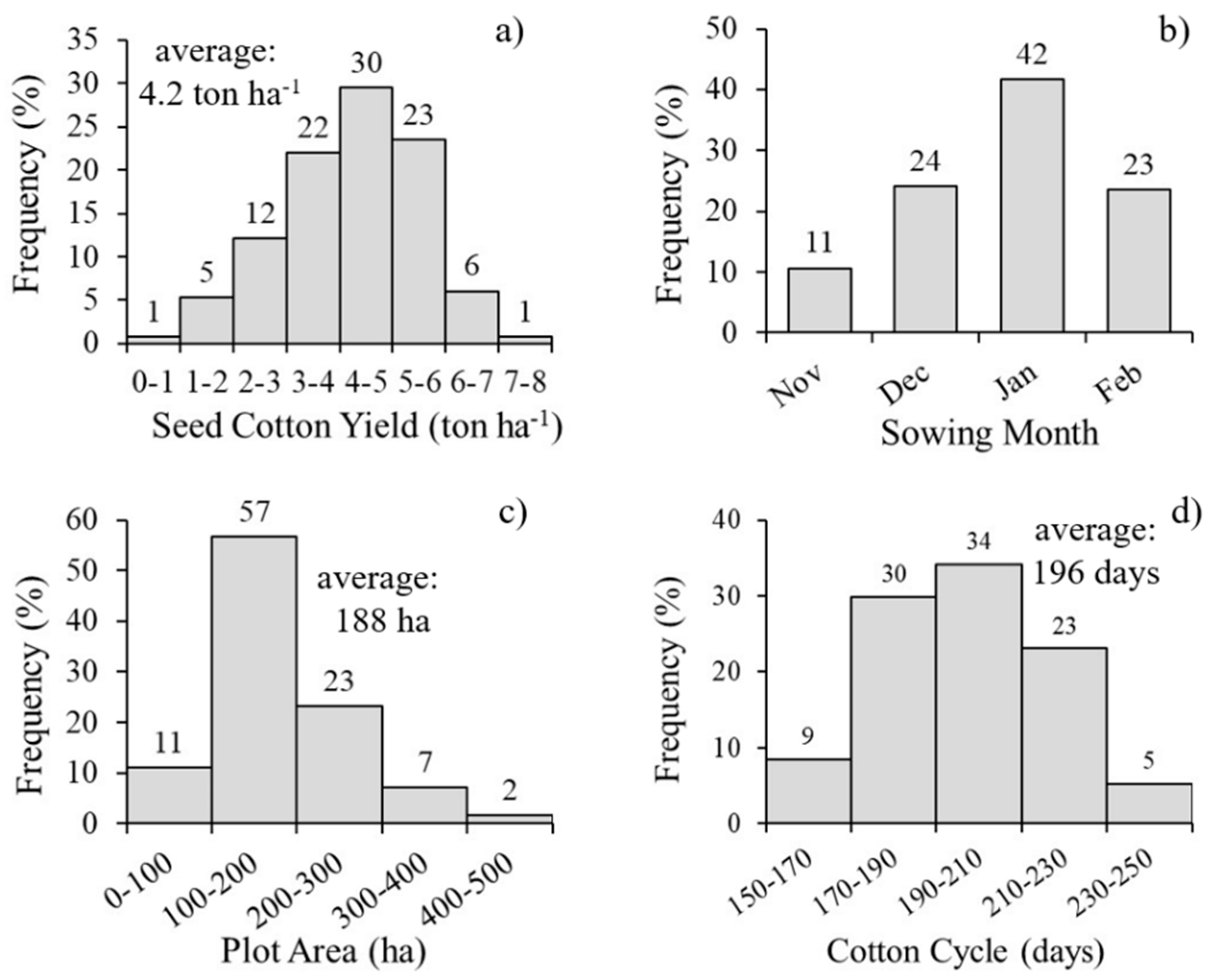

2.1. Experimental areas and dataset

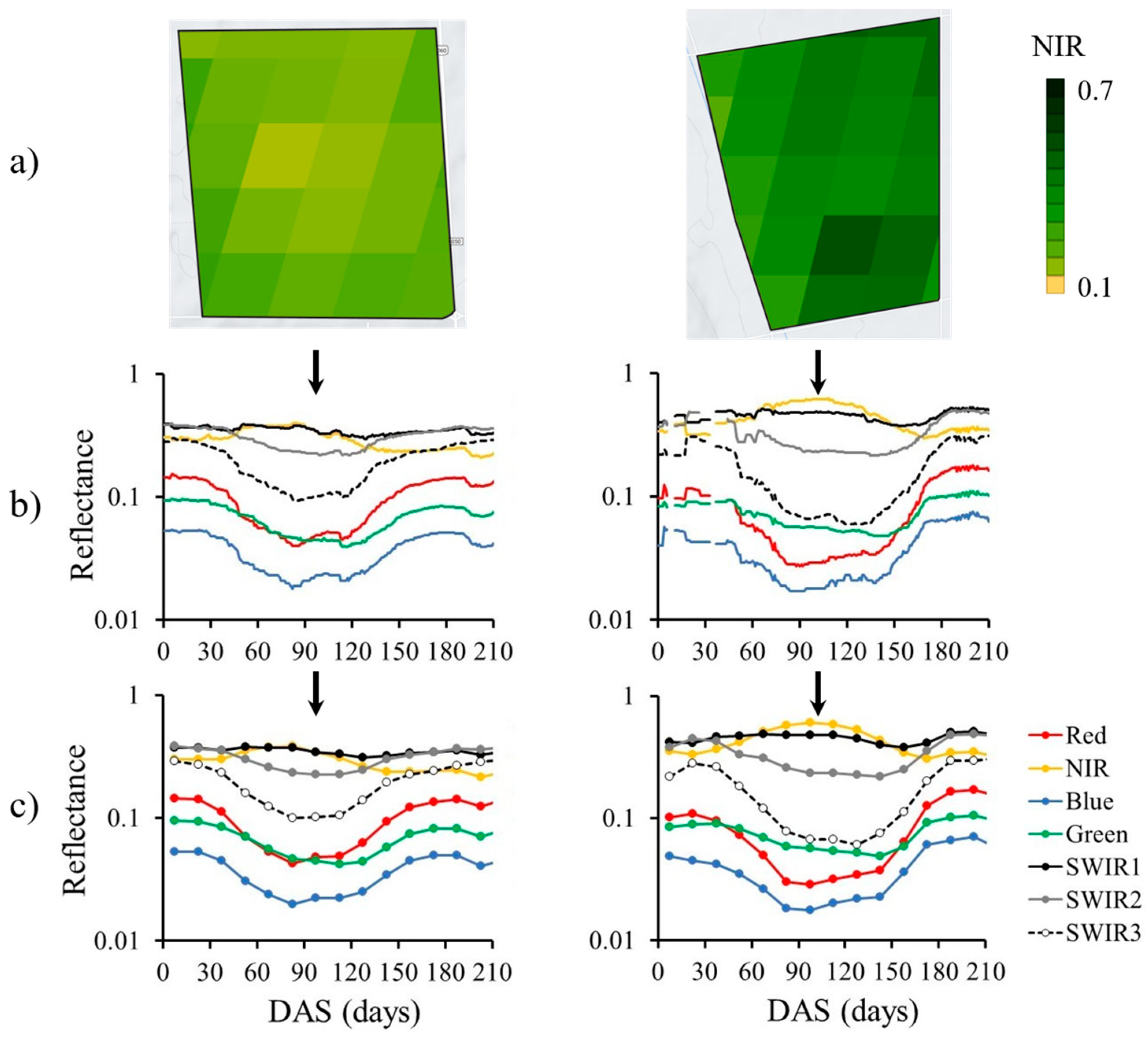

2.2. Satellite data acquisition and preprocessing

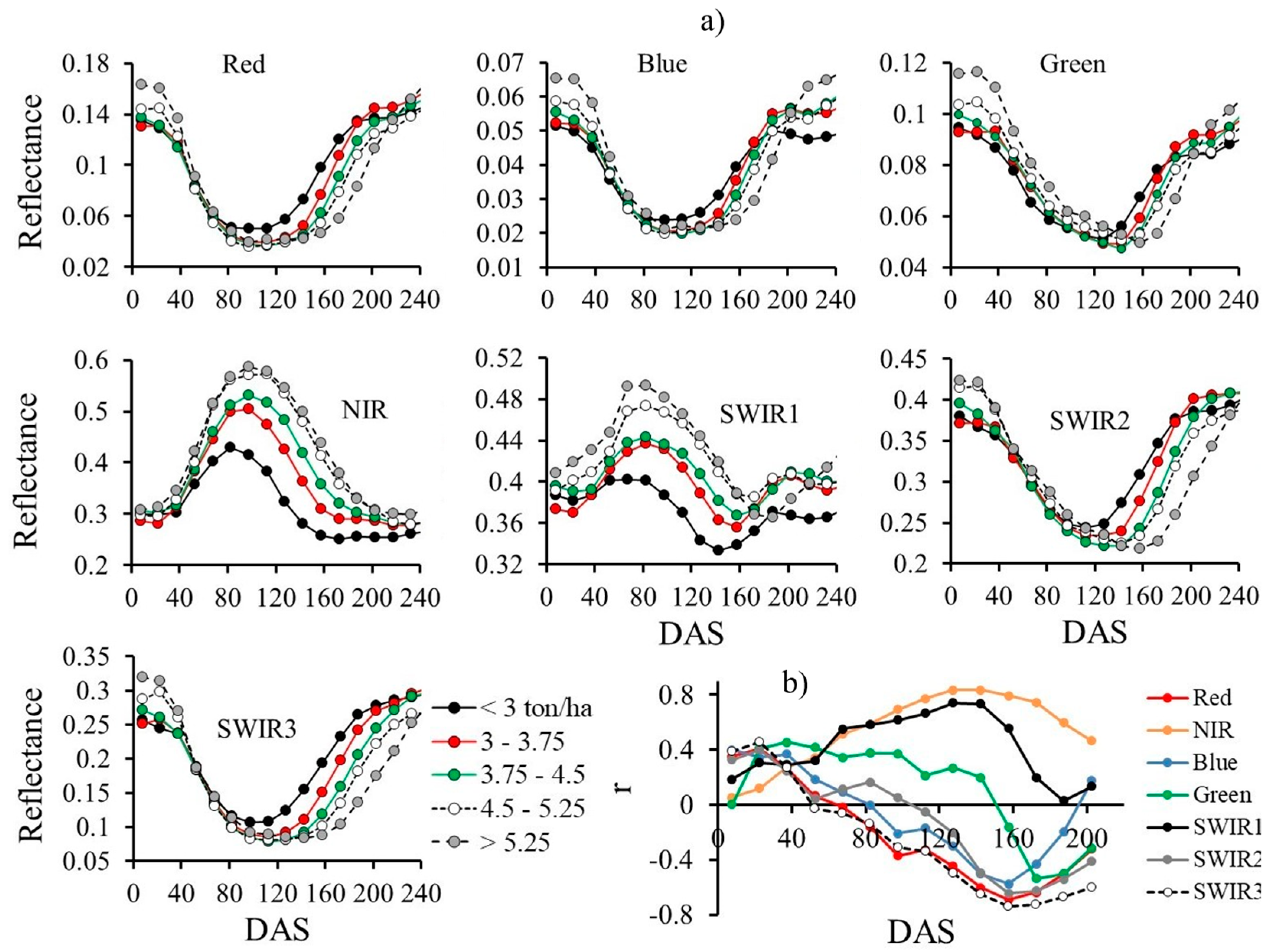

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments and Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ABRAPA. Safra Brasil. 2024. Available online: https://abrapa.com.br/dados/ (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Eiten, G. Cerrado vegetation: vegetation and climate in Brazil. In Pinto, M.N. (Org). Cerrado: characterization, occupation and perspectives (in Portuguese); UNB: Brasília, Brazil, 1993; pp. 17–73. [Google Scholar]

- COTTON BRAZIL, 2024. Market Report, January 19, 2024. Available online: file:///C:/Users/carlos.vaz/Downloads/ABRAPA_COTTON_BRAZIL_REPORT_-_2024_01-1.pdf . (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Echer, F.R.; Mello, P.R.; Rosolem, C.A. Management of plant growth regulators. In J.L. Belot and P.M.C.A. Vilela (ed.), Best Management Practices for Cotton in Mato Grosso State (in Portuguese), 4th ed.; IMAmt-AMPA: Cuiabá, MT, Brazil, 2020; pp. 312–319. [Google Scholar]

- CONAB. Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento. 2024. Available online: https://www.conab.gov.br/info-agro/safras/serie-historica-das-safras/itemlist/category/898-algodao (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Basso, B.; Liu, L. Seasonal crop yield forecast: Methods, applications, and accuracies. Adv. Agron. 2019, 154, 201–255. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Miao, Y.; Chen, X.; Sun, Z.; Stueve, K.; Yuan, F. In-season prediction of corn grain yield through PlanetScope and Sentinel-2 images. Agronomy, 2022, 12, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S.; Kushal, K.C.; Fulton, J.P.; Shearer, S.; Ozkan, E. Remote sensing in agriculture - Accomplishments, limitations, and opportunities. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskiner, T.; Bilgen, B. Optimization models for harvest and production planning in agri-food supply chain: A systematic review. Logistics 2021, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.; Zhang, L.; Huang, C.; Chen, J.; Kang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tong, Q. Integrating environmental and satellite data to estimate county-level cotton yield in Xinjiang Province. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1048479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, N.R.; Patel, N.R.; Danodia, A. Crop yield prediction in cotton for regional level using Random Forest approach. Spat. Inf. Res. 2020, 29, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, P.; Whelan, M.B.; Vervoort, R.W.; Bishop, T.F.A. Mid-season empirical cotton yield forecasts at fine resolutions using large yield mapping datasets and diverse spatial covariates. Agric. Syst. 2020, 184, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Ustin, S.L.; Zhang, X. Assessment of FSDAF accuracy on cotton yield estimation using different Modis products and Landsat based on the mixed degree index with different surroundings. Sensors 2021, 21, 5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.M.; Rosales, A.; Mueller, R.; Reynolds, C.; Frantz, R.; Anyamba, A.; Pak, E.; Tucker, C. USA crop yield estimation with MODIS NDVI: Are remotely sensed models better than simple trend analyses? Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.M. A comprehensive assessment of the correlations between field crop yields and commonly used MODIS products. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2016, 52, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Read, J.; Whisler, D. Using remote sensing and soil physical properties for predicting the spatial distribution of cotton lint yield. Turkish J. Field Crop. 2013, 18, 158–165. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, A.; Zhou, J.; Vories, E.D.; Sudduth, K.A.; Zhang, M. Yield estimation in cotton using UAV-based multi-sensor imagery. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 193, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A.; Zhang, M.; Sudduth, K.A.; Vories, E.D.; Zhou, J. Cotton yield estimation from UAV-based plant height. Trans. ASABE 2019, 62, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, C.; Hornbuckle, J.; Brinkhoff, J.; Smith, J.; Quayle, W. Assessment of in-season cotton nitrogen status and lint yield prediction from Unmanned Aerial System imagery. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Brand, H.J.; Sui, R.; Thomson, S.J.; Furukawa, T.; Ebelhar, M.W. Cotton yield estimation using very high-resolution digital images acquired with a low-cost Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Trans. ASABE 2016, 59, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Sui, R.; Thomson, J.S.; Fisher, D.K. Estimation of cotton yield with varied irrigation and nitrogen treatments using aerial multispectral imagery. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2013, 6, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Reddy, K.R.; Kakani, V.G.; Read, J.J.; Koti, S. Canopy reflectance in cotton for growth assessment and lint yield prediction. Eur. J. Agron. 2007, 26, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Qiu, B.; Cheng, F.; Chen, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D.; Lin, L.; Xu, A. National scale maize yield Estimation by integrating multiple spectral indexes and temporal aggregation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Huang, J.; Shen, Y.; Liu, S.; Huang, Y.; Dong, J. , Han, W.; Ye, T.; Zhao, W.; Yuan, W. A satellite-based method for national winter wheat yield estimating in China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbieri, R.; Vaz, C.M.P.; Pessatto-Filho, D.; Crestana, S.; Chitarra, L.G.; Lobo-Junior, M.; Lanças, F.M.; Silva, J.F.V.; Faleiro, V.O.; Sarques, B. Cotton production in Goiás: White mold, fusarium wilt, cultivation system and soil physical attributes (In Portuguese). Circular Técnica, Goiás, AGOPA, Brazil, 2018, 20p.

- Galbieri, R.; Vaz, C.M.P.; Silva, J.F.V.; Amus, G.L.A.; Crestana, S.; Matos, E.S.; Magalhaes, C.A.S. Influence of soil parameters on the occurrence of phytonematodes. In Rafel Galbieri; Jean Louis Belot. (Org.). Phytoparasitic nematodes of cotton in Brazilian cerrados: Biology and control measures (In Portuguese). 1ed. IMAmt Cuiabá, MT, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia., 2022. Boletim de Monitoramento Agrícola - Culturas de Verão 21/22, 11(5):1-19. Available online: https://portal.inmet.gov.br/ (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Perina, F.J.; Bogiani, J.C.; Ribeiro, G.C.; Breda, C.E.; Fabris, A.; dos Santos, I.A.; Seibel, D.P. Survey and management of phytonematodes in cotton in western Bahia, results for season 2016/17. Fundação BA, Bahia, Brazil, Circular Técnica, 2017, 8p.

- AGRITEMPO, 2024. Agrometeorological Monitoring System. Available online: http://www.agritempo.gov.br/agritempo/sobre.jsp?lang=en (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- QGIS Development Team. 2022. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. Available online: http://qgis.osgeo.org.

- Chattopadhyay, N.; Shukla, K.K.; Birah, A.; Khokhar, M.K.; Kanojia, A.K.; Nigam, R.; Roy, A.; Bhattacharya, B.K. Identification of spectral bands to discriminate wheat Spot Blotch using in situ hyperspectral data. J. Indian Soc. Remote. Sens. 2023, 51, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipling, E.B. Physical and physiological basis for the reflectance of visible and near-infrared radiation from vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1970, 1, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenkabail, P.S.; Smith, R.B.; De Pauw, E. Hyperspectral vegetation indices and their relationships with agricultural crop characteristics. Remote Sens. Environ. 2000, 71, 158–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, A.A.; Awoke, B.G. Evaluation of the saturation property of vegetation indices derived from sentinel-2 in mixed crop-forest ecosystem. Spat. Inf. Res. 2020, 1, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, N.; Huang, W.; Xie, Q.; Shi, Y.; Ye, H.; Dong, Y.; Wu, M.; Sun, G.; Jiao, Q. A transformed triangular vegetation index for estimating winter wheat leaf area index. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shammi, S.A.; Meng, Q. Use time series NDVI and EVI to develop dynamic crop growth metrics for yield modeling. Ecological Indicators, 2021, 121, 107124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashapure, A.; Jung, J.; Chang, A.; Oh, S.; Yeom, J.; Maeda, M.; Maeda, A.; Dube, N.; Landivar, J.; Hague, S.; Smith, W. Developing a machine learning based cotton yield estimation framework using multi-temporal UAS data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 169, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baio, F.H.R.; da Silva, E.E.; Martins, P.H.A.; da Silva-Júnior, C.A.; Teodoro, P.E. 2019. In situ remote sensing as a strategy to predict cotton seed yield. J. Biosci. 2019, 35, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, X.; Huanjun, L.; Guo, D.; Yan, Y.; Qin, L. , Pan, Y. Estimation of cotton yield using the reconstructed time-series vegetation index of Landsat data. Can. J. Remote. Sens. 2017, 43, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Ren, C.; Ustin, S.; Qiu, Z.; Xu, M.; Guo, D. Assessment of the effectiveness of spatiotemporal fusion of multi-source satellite images for cotton yield estimation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 162, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghverdi, A.; Washington-Allen, R.A.; Leib, B.G. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 152, 186–197. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.C.S.; Ferreira, G.B. Cotton liming and fertilization in the cerrado (in Portuguese). Circular Técnica 92, Embrapa, Campina Grande, PB, Brazil, 2006, 16p.

- Jeong, S.; Shin, T.; Ban, J.; Ko, K.J. Simulation of spatiotemporal variations in cotton lint yield in the Texas high plains. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Mostovoy, G. Cotton yield estimate using Sentinel-2 data and an ecosystem model over the southern US. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Gritz, Y.; Merzlyak, M.N. Relationships between leaf chlorophyll content and spectral reflectance and algorithms for non-destructive chlorophyll assessment in higher plant leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.F. Derivation of leaf-area index from quality of light on the forest floor. Ecology 1969, 50, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincini, M.; Frazzi, E.; D’Alessio, P. A broad-band leaf chlorophyll vegetation index at the canopy scale. Precis. Agric. 2008, 9, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broge, N.H.; Leblanc, E. Comparing prediction power and stability of broadband and hyperspectral vegetation indices for estimation of green leaf area index and canopy chlorophyll density. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 76, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the great plains with ERTS: Proceedings of the Third Earth Resources Technology Satellite-1 Symposium- Volume I: Technical Presentations. NASA SP-351 1974, 309-317.

| Vegetation Indices | Formulation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Green Index (GI) | GI = G/R | [44] |

| Ratio Vegetation Index (RVI) | RVI = NIR/R | [45] |

| Chlorophyll Vegetation Index (CVI) | CVI = (NIR*R)/G2 | [46] |

| Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) | SAVI = 1.5*(NIR-R)/(0.5*NIR+R) | [47] |

| Chlorophyll index - green (CIG) | CIG = (NIR/G)-1 | [44] |

| Triangular Chlorophyll Absorption Ratio Index (TVI) | TVI = 60*NIR-G-100*(R-G) | [48] |

| Green NDVI (GNDVI) | GNDVI = (NIR-G)/(NIR+G) | [49] |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) | EVI = 2.5*(NIR-R)/(1+NIR+6*R-7.5*B) | [50] |

| Normalized Differential Vegetation Index (NDVI) | NDVI = (NIR-R)/(NIR+R) | [51] |

| G: Green, R: Red, NIR: Near Infrared, B: Blue |

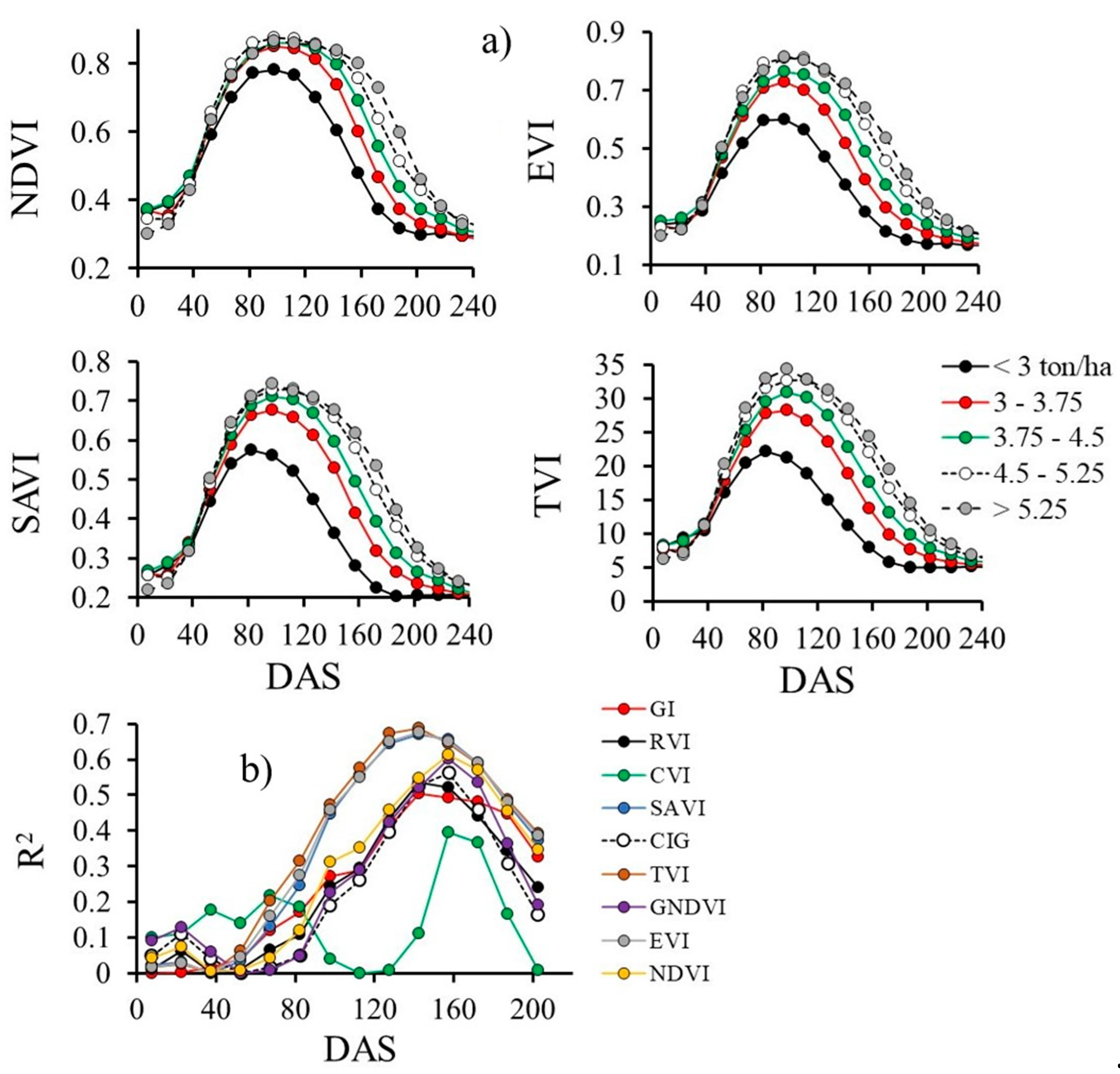

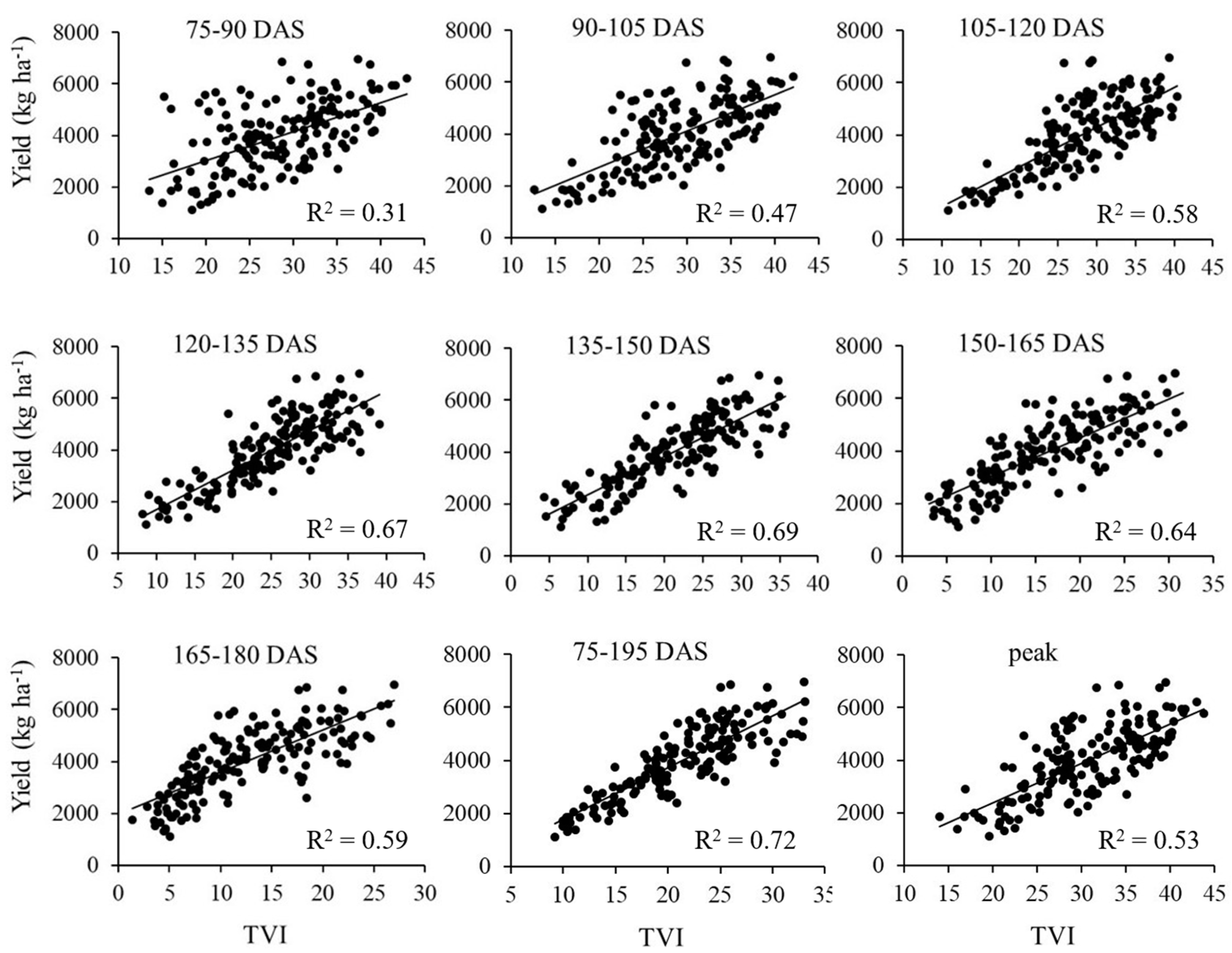

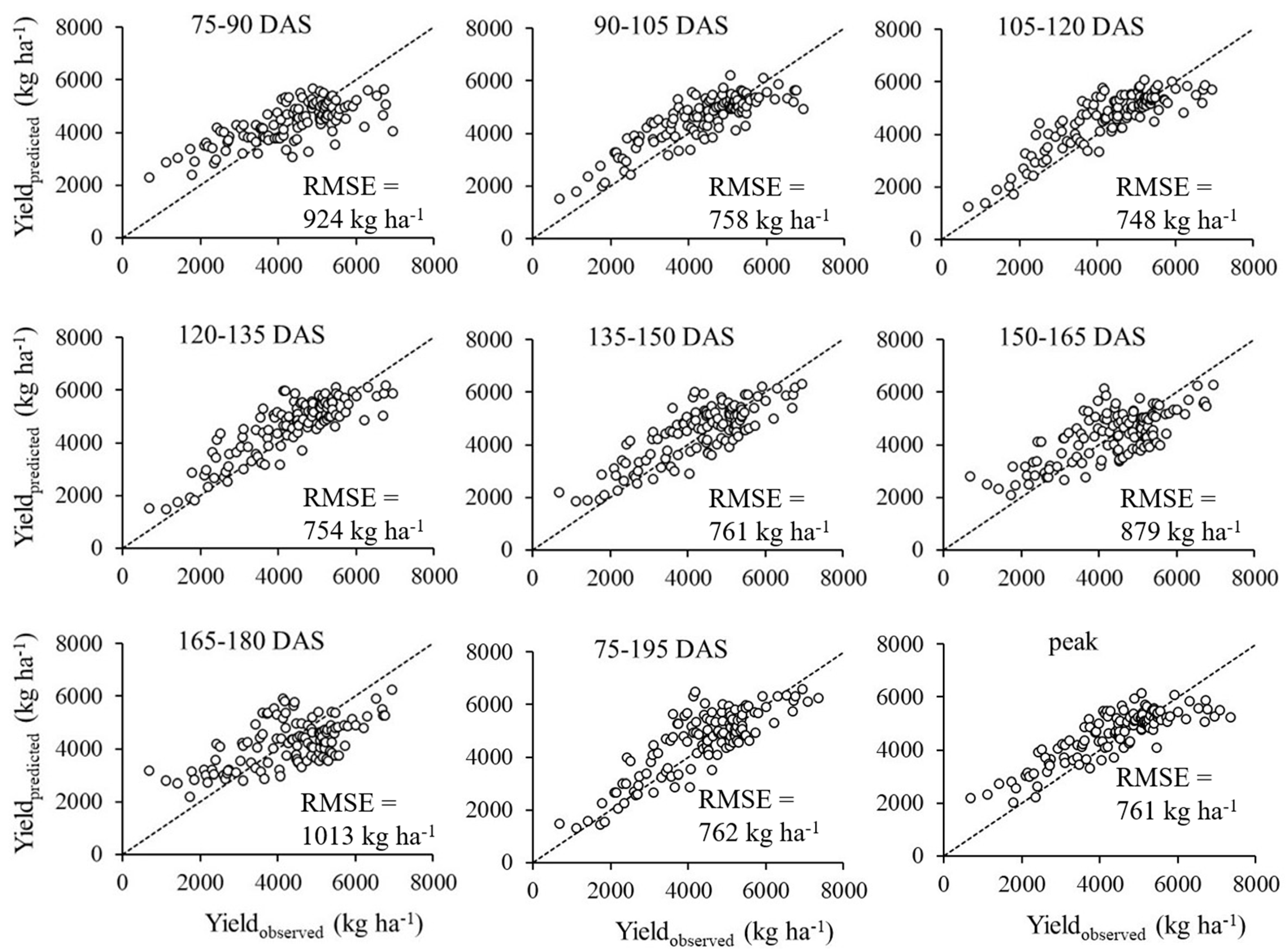

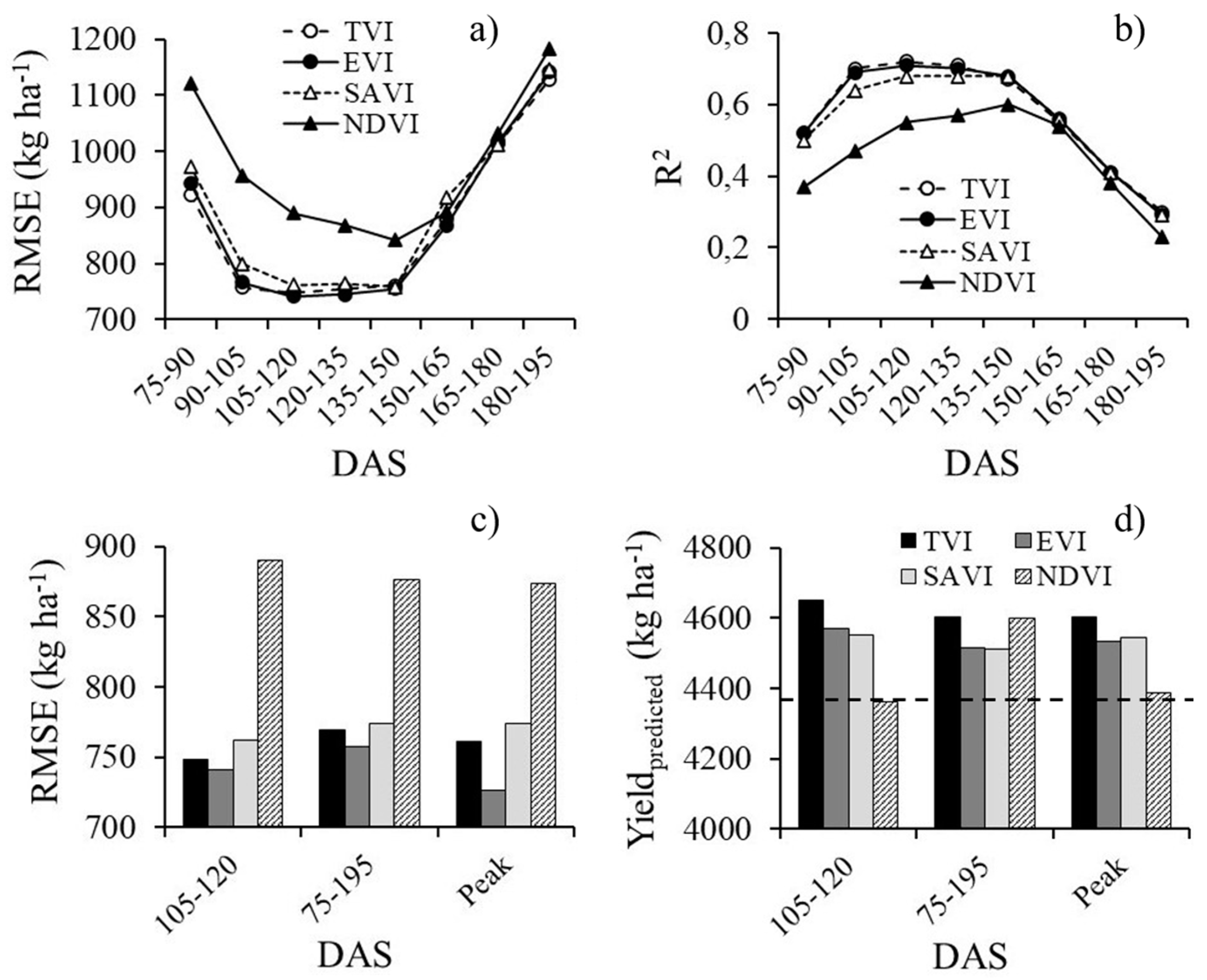

| DAS | Linear Model (TVI) | r2 | RMSE | DAS | Linear Model (EVI) | r2 | RMSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75-90 | Y = 111.96 TVI + 794.22 | 0.31 | 1088 | 75-90 | Y = 5133.1 EVI + 315.9 | 0.28 | 1119 | |

| 90-105 | Y = 139.78 TVI - 90.918 | 0.47 | 953 | 90-105 | Y = 6863.1 EVI - 1066.8 | 0.46 | 966 | |

| 105-120 | Y = 152.11 TVI - 269.52 | 0.58 | 856 | 105-120 | Y = 7316.1 EVI - 1249.5 | 0.55 | 879 | |

| 120-135 | Y = 152.87TVI + 166.22 | 0.67 | 752 | 120-135 | Y = 7013.0 EVI - 608.5 | 0.65 | 778 | |

| 135-150 | Y = 148.0 TVI + 878.89 | 0.69 | 735 | 135-150 | Y = 6484.9 EVI + 292.1 | 0.68 | 778 | |

| 150-165 | Y = 147.88 TVI + 1553.7 | 0.64 | 783 | 150-165 | Y = 6170.2 EVI + 1127.9 | 0.65 | 776 | |

| 165-180 | Y = 162.65 TVI + 1957.8 | 0.59 | 843 | 165-180 | Y = 6456.5 EVI + 1636.5 | 0.59 | 842 | |

| 180-195 | Y = 195.06 TVI + 2130.5 | 0.49 | 941 | 180-195 | Y = 7602.2 EVI + 1801.6 | 0.48 | 947 | |

| 75-195 | Y = 196.28 TVI - 189.77 | 0.72 | 690 | 75-195 | Y = 8891.9 EVI - 1026.2 | 0.73 | 688 | |

| Peak | Y = 150.52 TVI - 634.87 | 0.53 | 900 | Peak | Y = 7813.9 EVI - 1996.1 | 0.53 | 901 | |

| DAS | Linear Model (SAVI) | r2 | RMSE | DAS | Linear Model (NDVI) | r2 | RMSE | |

| 75-90 | Y = 6804.1 SAVI - 543.3 | 0.25 | 1140 | 75-90 | Y = 6111.6 NDVI - 1057.4 | 0.12 | 1232 | |

| 90-105 | Y = 9495.4 SAVI - 2479.4 | 0.45 | 977 | 90-105 | Y = 11059 NDVI - 5334.6 | 0.31 | 1089 | |

| 105-120 | Y = 10008 SAVI - 2696 | 0.55 | 1132 | 105-120 | Y = 11093 NDVI - 5287.1 | 0.35 | 1058 | |

| 120-135 | Y = 9164.3 SAVI - 1712.5 | 0.64 | 784 | 120-135 | Y = 9500.8 NDVI - 3674.2 | 0.46 | 966 | |

| 135-150 | Y = 7937.6 SAVI - 415.88 | 0.67 | 753 | 135-150 | Y = 7473.6 NDVI - 1618 | 0.55 | 884 | |

| 150-165 | Y = 7729.7 SAVI + 624.53 | 0.66 | 809 | 150-165 | Y = 6243.6 NDVI - 80.36 | 0.61 | 816 | |

| 165-180 | Y = 7244.4 SAVI + 1251.7 | 0.59 | 840 | 165-180 | Y = 5550.8 NDVI + 1002 | 0.57 | 861 | |

| 180-195 | Y = 8316.9 SAVI + 1422.3 | 0.47 | 952 | 180-195 | Y = 5922.8 NDVI + 1386.4 | 0.46 | 970 | |

| 75-195 | Y = 11152 SAVI - 2066.5 | 0.73 | 688 | 75-195 | Y = 11230 NDVI + 4003.9 | 0.67 | 752 | |

| Peak | Y = 11045 SAVI - 3770 | 0.51 | 919 | Peak | Y = 15470 SAVI – 9331.6 | 0.39 | 1029 | |

| Y: seed cotton yield (kg ha-1); Peak: maximum value of the VI in the time-series | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).