1. Introduction

In the study of housing markets,

understanding the determinants of housing prices is of paramount importance for

policymakers, investors, and researchers alike. Traditionally, many studies

have approached this issue by considering housing demand and supply as separate

entities, estimating their effects on prices independently. However, this

approach overlooks the intricate interplay between these factors and may yield

inconsistent or unreliable results. For example, common proxies for demand

include income levels, population growth, and interest rates. These variables

provide insights into the purchasing power of potential homebuyers. The impact

of the variables however, does very much depend on the inventory or number of

vacant units. Similarly, indicators such as housing units-constructed,

building permits or land availability are considered as proxies for housing

supply. But the developers’ decisions on new developments are

shaped by the level of inventory within the market.

It is understandable that treating

demand and supply factors as separate entities is a practical solution to

maintain model simplicity and estimation viability. However, some previous

studies using separate demand-supply variables have found unexpectedly contradictory

effects of supply, resulting in misinterpretations of the true drivers of

housing price fluctuations.

To address these limitations, this

study proposes a novel approach by utilising number of vacant units as a proxy

for the net effect of supply and demand interactions on housing prices. By

incorporating the number of vacant units as a determinant of

housing prices, this study aims to analyse the net impact of the interplaying dynamics

between housing supply and demand on housing prices. Specifically, the study

hypothesises that changes in the number of vacant units will reflect

the equilibrium between housing supply and demand, thus exerting a significant

influence on housing prices.

It is well recognised that

frequent housing vacancy data is often hardly available. Vacancy data is

usually collected once every five years during the census, and

accuracy of the data is hard to ascertain. This may explain why vacancy

rates are not commonly used in studies of housing prices determinants. This

study uses the annual data series of the numbers of vacant units

of five different classes of housing in Hong Kong to examine the validity of

the proposed hypothesis.

The preliminary findings suggest

that changes of the number of vacant units impose a negative effect on

changes of real housing prices, aligning with theoretical predictions. This

underscores the importance of considering vacancy as a crucial determinant of

housing prices, as vacancy encapsulates the outcome of the intricate

interplay between the housing supply and demand dynamics. Through this

innovative approach, the study aims to provide a more comprehensive

understanding of the determinants of housing prices and contribute to more

robust policymaking and investment strategies in the housing sector.

The paper is organised as follows: Section 2 is a literature review on existing studies

of the determinants of housing prices and vacancy rates. Section 3 outlines the research materials and

methods used. Section 4 reports the

results of the empirical tests. Section 5

discusses the findings and implications. Section

6 concludes.

2. Literature Review

Supply-side Determinants of Housing Prices

The broad and diverse nature of

residential housing markets means that there are various demand and supply side

factors that interact to achieve an equilibrium and result in market housing

prices (Xu and Tang, 2014). Sirmans et al. (2006), however, found the existing

literature failed to reach a common consensus on the effect of different

determinants on housing prices through hedonic pricing models. It implies that

the outcomes of the studies can vary greatly depending on the model

specifications. This variation can challenge the robustness of the findings.

The results of housing supply

determinants are particularly confusing. There have been studies finding that

housing supply is positively associated with housing prices which contradicts

the prediction of the Law of Supply. The results are posited to support that

housing supply change is determined by housing price change, instead of its

determinant. For example, both Glindro et al. (2007) and Belke & Keil

(2017) found a positive and significant association between land or housing

supply and housing prices. Glindro et al. (2007: 186) studied determinants of

house prices in nine Asia-Pacific economies. They concluded that “the

coefficient of the land supply index is positive, which contradicts the

theoretical prediction that increases in land supply have a dampening effect on

house prices.” They tried to explain the contradictory results by contending

that “higher house prices provide an incentive for developers to build up new

residential property projects.” Similarly, Belke & Keil (2017: 14) analysed

a panel dataset of nearly 100 German cities, with both supply-side and

demand-side factors. They found that, among others, “The positive relation

between construction activity and real estate prices could reflect a supply side

reaction of increasing construction in cities with strong demand.” Many other

studies found no significant results of housing supply. For example, Taghizadeh-Hesary,

Yoshino & Chiu (2019: 18) of ADBI analysed a time series dataset in

1999–2018 of macroeconomic variables and housing prices in Hong Kong, and they also

found that, among others, “housing supply has never been statistically

significant; housing supply is not responsible for or affected by, or does it

respond to price changes”.

In contrast, there are studies

that claimed to find a negative association between housing supply and prices.

Geng (2018), for instance, studied determinants of house prices of 20 advanced

economies by a cross-country panel model and found a negative effect of housing

supply on house prices. Yet, the proxy of supply is housing stock per capita.

Similarly, Dröes & van de Minne (2017) also found a negative

relationship between housing supply and prices by using the total number of

housing units in Amsterdam as the proxy of supply.

Demand-side Determinants of Housing Prices

Studies on demand-side

determinants of housing prices do have consistent results, especially on investment

demand proxies, such as interest rates and GDP. Égert & Mihaljek (2007)

studied the determinants of house prices in eight transition economies of

Europe and 19 OECD countries and found that real interest rates and GDP per

capita are two strong demand-side price determinant. These two demand-side

price determinants are echoed through other studies that often use interest

rates, GDP or a subsidiary of GDP as a means to understand the demand side

pressures impacting upon house prices. (Glindro et al., 2007; Xu & Tang,

2014; Dröes & van de Minne, 2017; Taghizadeh-Hesary,

Yoshino & Chiu, 2019; Yiu, 2021).

Studies on Housing Vacancy

Instead of including separate

proxies of housing demand and supply, Égert & Mihaljek (2007: 3) contended

that “both the supply and demand for housing interact to determine an

equilibrium level for real house prices”. But they did not identify any proxies

of the interaction results.

Theoretically, Wheaton (1990: 1290)

developed one of the first housing vacancy model which “suggests that small

changes in supply or demand, as they alter vacancy, can have very profound

impacts on market prices.” Understanding the intricate relationship between

housing prices and vacancy rates is crucial for policymakers, real estate investors,

and analysts alike. However, as reviewed above, very few studies on house

prices determinants would include vacancy as a determinant, probably due to the

unavailability of vacancy time series. Previous studies on housing vacancy often

relied on cross-sectional data, such as Lerbs & Teske (2016), which are

hard to control all spatial differences and could not capture the temporal

dynamics adequately. Furthermore, such cross-sectional studies are susceptible

to endogeneity and omission biases, casting doubts on the reliability of their

findings. Thus, this study attempts to analyse the temporal effects of vacancy

changes on housing price changes, ceterus paribus.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

The dataset for this study is collected from Rating

and Valuation Department (RVD, 2024) which provides yearly

vacancy rates and housing prices for five distinct classes of housing units, categorised

by their floor areas, in Hong Kong. Other demographic and macroeconomic data

are collected from Census and Statistics Department (C&SD, 2024). Both time

series and panel analysis methods are employed to investigate the relationship

between housing vacancies and prices over time, controlling for various housing

sizes and temporal factors.

Housing data in Hong Kong are reported in five

classes, based on the saleable area of housing units, viz. (a) Class A – less

than 40 sq. m.; (b) Class B – from 40 to 69.9 sq. m.; (c) Class C – from 70 to

99.9 sq. m.; (d) Class D – from 100 to 159.9 sq. m.; and (e) Class E – from 160

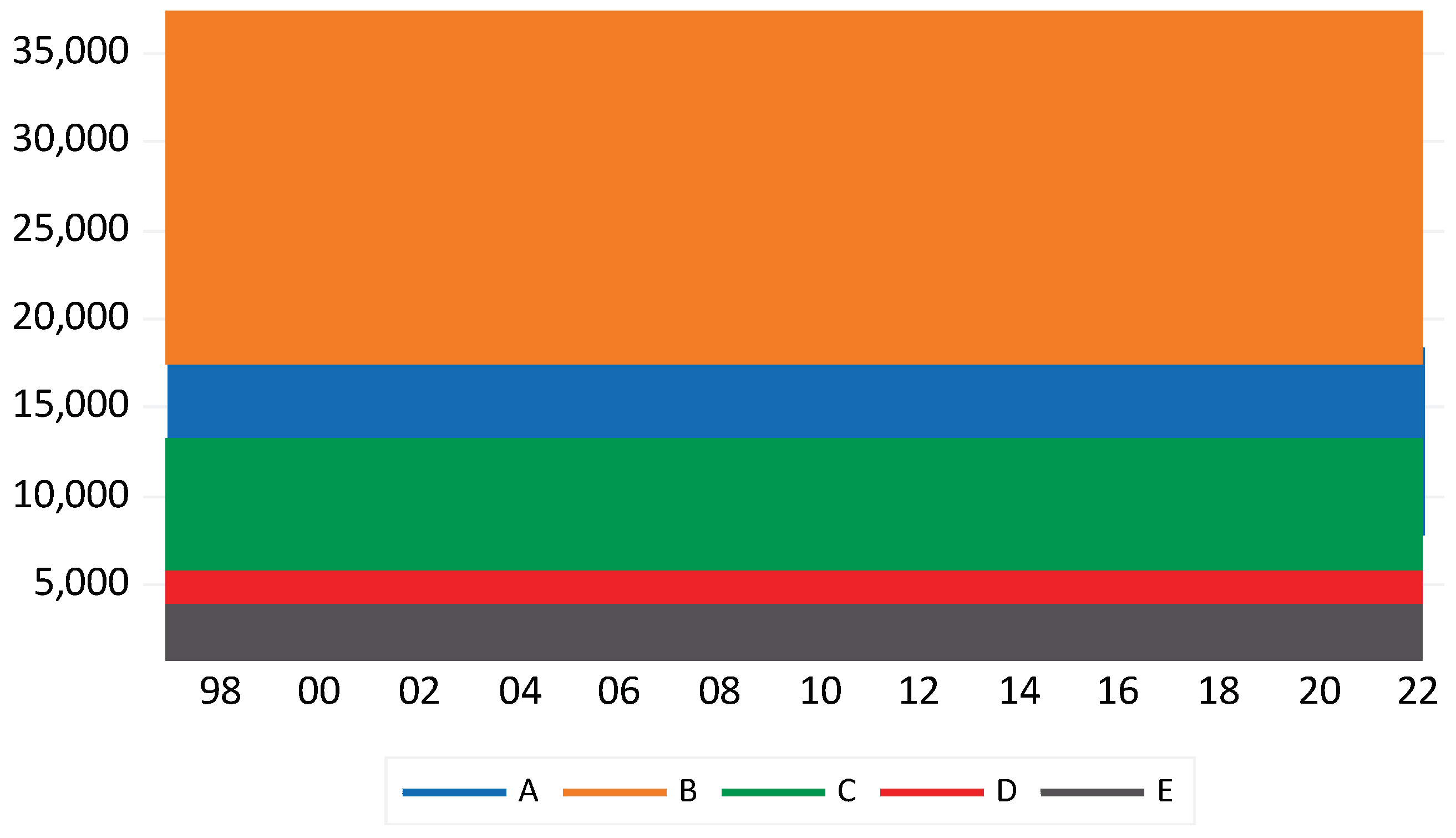

sq. m. and above. Figure 1 shows the vacancies of the five classes of

housing in Hong Kong from 1997 to 2022. Classes A and B are the dominant sizes

as they account for 80% (A: 32% and B: 48%) of total housing stock (1,256,772)

in 2022. Classes C, D and E account for 12%, 6%, and 2% respectively (RVD, 2024).

Figure 1.

Vacancies of the five classes of housing in Hong Kong from 1997 to 2022. Source: RVD (2024). Legends: Classes of housing are categorised based on the saleable area of housing units, viz. (a) Class A – less than 40 sq. m.; (b) Class B – from 40 to 69.9 sq. m.; (c) Class C – from 70 to 99.9 sq. m.; (d) Class D – from 100 to 159.9 sq. m.; and (e) Class E – from 160 sq. m. and above.

Figure 1.

Vacancies of the five classes of housing in Hong Kong from 1997 to 2022. Source: RVD (2024). Legends: Classes of housing are categorised based on the saleable area of housing units, viz. (a) Class A – less than 40 sq. m.; (b) Class B – from 40 to 69.9 sq. m.; (c) Class C – from 70 to 99.9 sq. m.; (d) Class D – from 100 to 159.9 sq. m.; and (e) Class E – from 160 sq. m. and above.

The vacancy of small-sized residential units (Class

A) shows a recent increasing trend, while the vacancies of medium-sized

residential units (Classes B and C) rose to the peak in around 2002-2003 and

then fell afterwards. The vacancies of large units have remained relatively

steady.

Similarly, the yearly series of housing completion rate

of each housing class is collected from the RVD (2024). Demand proxies,

including population, real GDP, interest rate, are common to all housing

classes. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables, and Table 2 shows their stationarities by the Levin, Lin & Chu test and the Im,

Peasaran and Shin test. They show that all series are stationary in their first

differences.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables, 1997–2022. Sources: RVD (2024) & C&SD (2024).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables, 1997–2022. Sources: RVD (2024) & C&SD (2024).

| Variable |

Class |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Minimum |

Maximum |

| Natural logarithm of the real housing price index of class i in year t, ln(RHPt) |

A |

0.75 |

0.53 |

-0.10 |

1.46 |

| B |

0.70 |

0.46 |

-0.08 |

1.32 |

| C |

0.73 |

0.40 |

-0.01 |

1.24 |

| D |

0.77 |

0.37 |

0.06 |

1.20 |

| E |

0.83 |

0.36 |

0.15 |

1.21 |

| Combined |

0.73 |

0.47 |

-0.07 |

1.36 |

| Natural logarithm of the number of vacant housing units of class i in year t, ln(VACt) |

A |

9.34 |

0.26 |

9.00 |

9.80 |

| B |

10.11 |

0.24 |

9.79 |

10.53 |

| C |

8.98 |

0.24 |

8.47 |

9.49 |

| D |

8.40 |

0.22 |

7.74 |

8.64 |

| E |

7.80 |

0.30 |

6.99 |

8.25 |

| Combined |

10.85 |

0.17 |

10.49 |

11.21 |

| Natural logarithm of the number of class i housing units completed in year t, ln(COMt) |

A |

7.81 |

0.90 |

5.92 |

9.20 |

| B |

9.06 |

0.55 |

8.01 |

9.95 |

| C |

7.87 |

0.48 |

7.10 |

8.89 |

| D |

6.92 |

0.51 |

5.52 |

7.66 |

| E |

5.98 |

0.44 |

4.80 |

6.79 |

| Combined |

9.70 |

0.44 |

8.88 |

10.47 |

| Natural logarithm of the population in year t, ln(POPt) |

- |

15.77 |

0.04 |

15.69 |

15.83 |

| Natural logarithm of real gross domestic products in year t, ln(RGDPt) |

- |

10.05 |

0.17 |

9.74 |

10.29 |

| Interbank 3-month offer interest rate of Hong Kong in year t, IRt

|

- |

0.86 |

3.94 |

-4.87 |

10.11 |

| Period |

1997–2022 |

| Number of Observations |

130 Obs (26 periods × 5 classes) |

Table 2.

Unit Root Tests of Variables, 1997–2022.

Table 2.

Unit Root Tests of Variables, 1997–2022.

| Variable |

Level |

First-Difference |

| Time Series |

ADF |

PP |

ADF |

PP |

|

ln(RHPt) |

-0.30 |

-0.35 |

-4.56 *** |

-4.56 *** |

|

ln(VACt) |

-2.49 |

-2.51 |

-5.36 *** |

-5.36 *** |

|

ln(COMt) |

-1.28 |

-1.93 |

-7.87 *** |

-7.78 *** |

|

ln(POPt) |

-1.64 |

-1.57 |

-5.73 *** |

-6.10 *** |

|

ln(RGDPt) |

-1.20 |

-1.28 |

-5.16 *** |

-5.27 *** |

| IRt |

-2.79 * |

-1.69 |

- |

- |

| Panel |

Levin, Lin & Chu t* |

Im, Peasaran and Shin W-stat |

Levin, Lin & Chu t* |

Im, Peasaran and Shin W-stat |

|

ln(RHPt) |

0.87 |

2.11 |

-6.03 *** |

−5.31 *** |

|

ln(VACt) |

-1.90 ** |

-1.84 ** |

-4.84 *** |

-7.39 *** |

|

ln(COMt) |

-1.41 * |

-2.68 *** |

-9.14 *** |

-10.00 *** |

|

ln(POPt) |

-1.90 ** |

1.02 |

-8.60 *** |

-9.70 *** |

|

ln(RGDPt) |

-1.85 ** |

0.82 |

-8.58 *** |

−8.03 *** |

| IRt |

-3.53 *** |

-3.06 *** |

- |

- |

3.2. Research Design

A time series regression model and a five-class panel regression model (Equation (1)) use the traditional approach of separated variables for housing demand and supply are conducted as the baseline models. Population, real GDP and interest rate are incorporated to estimate demand effects, whereas housing completion is taken as the proxy of housing supply. Corresponding models (Equation (2)) uses the number of vacant housing units as an indicator of net demand which is then exploited to test the vacancy hypothesis. Interest rate variable is retained to estimate investment demand, which is less affected by vacancy rate.

where

RHPit,

POPt,

RGDPt,

IRt,

COMit, and

VACit, are real house price indices, population, real gross domestic products, interest rates, number of housing units completed and number of vacant units (of class

i in panel models or of the combined series in time series models) at time

t.

control cross-class fixed effects in the panel model,

caters for the autoregressive effect of house price changes in a one-year lag.

are coefficients to be estimated.

is the error term.

In the time series models, the combined series of real house price index, vacancies and completions are directly provided by RVD (2024). The Autoregressive Moving Averages (ARMA) model is applied to analyse the time series variables, using the Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) method to estimate the coefficients of the ARMA models. The BFGS algorithm is a numerical optimisation technique commonly used to maximise the likelihood function in Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE).

The panel models control class-specific factors by a cross-sectional fixed effect such as the policy changes in stamp duty and mortgage lending. The Panel Error Components Generalised Least Squares (EGLS) method. Since we found a significant cross-section dependence (correlation) between price changes of different housing classes, as shown in the Breusch-Pagan Lagrange Multiplier test (statistic=239.5, df=10, p=0.000), a cross-section seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) is used as generalised least squares (GLS) weights in the panel models to estimate the parameters. Furthermore, a Panel-Corrected Standard Errors (PCSE) technique is applied to correct the standard errors and covariance matrix of the estimated coefficients to address heteroscedasticity issue.

4. Results

Utilising both time series and panel regression models, Models 1a and 1b in Table 3 show the results of the temporal impacts of separate demand and supply factors as well as net demand factor proxied by changes of number of vacant units on housing price changes, with housing size effects fixed in the panel analysis. In the baseline models, the results show a negative effect of population size change in both models, which contradicts theoretical prediction. Also, a 1% increase in real GDP is found to have a positive (about 2% increase) and significant impact on housing prices in both models. Interest rate effect is negative as expected, however, it is insignificant in the time series model, and marginally significant in the panel model. Housing supply proxied by changes of housing completion is found to impose a negative effect on housing prices, but statistically insignificant in both models. The results of parameters in contradictory sign and of weak significance in most of the demand and supply variables agree with that of many previous studies and indicate a potential model misspecification.

However, housing supply is commonly agreed to be inelastic and takes time to complete. Model 2b of Table 3 shows a stronger and significant negative effect of housing supply if a 3-year lead is considered. Yet, how long being the lagging period is an empirical question and can vary over time. Due to the lagging nature of supply responses, it supports the use of vacancy data to estimate the net demand effect, as it represents the actual dynamics of demand and supply at any point of time.

Models 3a and 3b of Table 3, showed a consistently negative and significant effect of vacancy on housing prices, no matter in time series or in panel models. These findings suggest that housing vacancy is a price determinant, reflecting the net result of a dynamic interplay between housing demand and supply. The panel analysis allows us to disentangle the temporal trends from housing size factors, providing a more accurate depiction of the housing vacancy price relationship. The results highlight the importance of considering both temporal and spatial dimensions in understanding the complex dynamics of the real estate market.

Models 4a and 4b of Table 3 further divide housing demand into investment demand and accommodation demand, vacancy is assumed to be the net demand of accommodation and interest rate is considered as a proxy of investment demand which is independent of accommodation demand. The effect of vacancies on housing prices is quite similar to Models 3a and 3b. The interest rate effect is found, as expected, to be negative and significant and the magnitude is about the same as in Models 2a and 2b, supporting the use of vacancy variable as a proxy of net accommodation demand.

Table 3.

Results of the time series and panel regression models on the determinants of house price change.

Table 3.

Results of the time series and panel regression models on the determinants of house price change.

| Dependent Variable |

dln(RHPt) |

dln(RHPit) |

| Variables |

Time Series Model 1a |

Time Series Model 2a |

Time Series Model 3a |

Time Series Model 4a |

Panel

Model 1b

|

Panel

Model 2b

|

Panel

Model 2b

|

Panel

Model 3b

|

|

dln(POPt) |

-3.272

(-0.52) |

-14.609

(-1.61) |

- |

- |

-6.999

(-1.91) *

|

-16.134

(-3.56) ***

|

- |

- |

|

dln(COMit) |

-0.004

(-0.05) |

- |

- |

- |

-0.002

(-0.66) |

- |

- |

- |

|

dln(COMit+3) |

- |

-0.047

(-0.73) |

- |

- |

- |

-0.008

(-2.67) ***

|

- |

- |

|

dln(RGDPt) |

2.131

(3.67) **

|

2.907

(6.58) ***

|

- |

- |

2.241

(5.47) ***

|

3.033

(7.94) ***

|

- |

- |

|

dln(VACit) |

- |

- |

-0.795

(-3.18) **

|

-0.630

(-2.15) **

|

- |

- |

-0.024

(-2.89) ***

|

-0.022

(-3.04) ***

|

| IRt |

-0.018

(-1.45) |

-0.017

(-0.94) |

- |

-0.013

(-1.04) |

-0.014

(-1.67) *

|

-0.025

(-2.40) **

|

- |

-0.026

(-2.53) **

|

|

AR(1) |

0.187

(0.78) |

0.598

(1.96) *

|

-0.505

(-2.88) ***

|

-0.538

(-2.23) **

|

0.208

(2.40) **

|

0.435

(4.80) ***

|

0.185

(1.58) |

0.121

(1.29) |

| Constant |

0.056

(1.21) |

0.129

(1.57) |

0.041

(2.29) **

|

-1.216

(-1.01) |

0.059

(1.86) *

|

0.124

(2.82) ***

|

0.026

(0.74) |

0.086

(2.56) **

|

| Fixed Effect |

NA |

Yes (on housing classes) |

| Model |

ARMA Maximum Likelihood (BFGS) |

Panel EGLS (Cross-section SUR) with cross-section weights (PCSE) std errors & covariance |

| Sample (year) |

1997-2022 |

| No. of Obs. |

26 |

23 |

26 |

26 |

130 (26x5) |

115 (23x5) |

130 (26x5) |

130 (26x5) |

| Adj. R-Squared |

0.34 |

0.50 |

0.16 |

0.22 |

0.20 |

0.43 |

0.04 |

0.11 |

5. Discussion

The use of separate variables to estimate housing demand and supply effects on prices can be shown to be biased by a simple thinking experiment. Imagine whenever housing demand increases/decreases, housing supply increases/decreases at the same time but with 50% quantity. In other words, net demand will be positive/negative when demand increases/decreases. However, in a traditional regression model with separate proxies for demand and supply, since both of them always move in the same direction as in this case, their effects on prices would be of the same sign, which is contradictory to the Laws of Supply and Demand. It is because they are assumed to be independent in the regression model, but in reality, they are inextricably intertwined. It can be rectified by using net demand, that is the resultant of the interplay of housing demand and supply, which reflect the actual lagging nature and inelasticity of housing supply of the housing markets.

The availability and accuracy of vacancy data are crucial for understanding and predicting housing market dynamics, including the determinants of housing prices. However, traditional methods of collecting vacancy data, such as those conducted during the census once every five years, present challenges due to their infrequency and varying definitions across different jurisdictions. Fortunately, advancements in technology, particularly the digitalisation of utility meters, offer a promising solution to these challenges. By leveraging the data from digital electricity and water meters, cities can standardise the definition of vacant homes and collect meaningful vacancy data for housing price analysis.

In recent years, the digitalisation of utility meters, particularly electricity and water meters, has transformed the way utility consumption data is collected and analysed (Razavo, et al., 2019; Newing et al., 2023). Digital meters provide real-time monitoring of energy and water usage in homes, offering a wealth of data that can be leveraged to identify vacant properties. By setting a threshold for electricity and/or water consumption below which a property is considered vacant, cities can establish a standardised definition of vacant homes, overcoming the inconsistencies associated with traditional vacancy data collection methods.

Leveraging digital utility meters for vacancy data collection offers several advantages. First and foremost, it enables real-time monitoring of vacancy rates, allowing policymakers and researchers to track changes in housing market dynamics more accurately and promptly. Second, by standardising the definition of vacant homes based on utility consumption thresholds, cities can ensure consistency and comparability in vacancy data across different jurisdictions. This enhances the reliability and usefulness of vacancy data for housing price analysis and policymaking. Additionally, the use of digital utility meters reduces the burden and cost associated with traditional vacancy surveys, as data collection can be automated and conducted remotely.

The availability of standardised vacancy data collected through digital utility meters opens up new possibilities for analysing the determinants of housing prices. Researchers can incorporate vacancy data as an important explanatory variable in econometric models of housing prices, providing insights into the relationship between housing supply and demand dynamics. By leveraging real-time vacancy data, policymakers can develop more effective strategies to address housing market imbalances and promote housing affordability. Furthermore, the standardised nature of vacancy data collected through digital utility meters facilitates cross-city and cross-country comparisons, enabling researchers to identify trends and best practices in housing market regulation and policy implementation.

6. Conclusions

This is probably the first time series and panel analysis study of housing vacancies effect on prices. One of the major implications of the study is on identifying net demand determinants of housing prices. Traditionally, studies on price determinants treated housing supply and demand as separate independent variables in regression models, overlooking their interdependence. However, market prices emerge from the intricate interplay between supply and demand forces. Meaning they could not be independent. Also, finding appropriate proxies of housing demand can be challenging, as it is an economic construct rather than a directly observable information. Many previous studies considered population size and gross domestic products as demand proxies, without considering housing supply responses. Even if the studies incorporate proxies of supply, insignificant results or even contradictory results are often estimated. This study challenges the conventional approach by considering housing vacancy changes as outcomes of the interactions between supply and demand, i.e. net demand of accommodation. It can reflect accurately the dynamics of demand and supply of accommodation. A higher vacancy signifies an increased number of housing units that are neither utilised for owner-occupation nor rented out. The underlying reasons for such vacancies are diverse, including potential over-supply of building units in the market or an economic downturn leading to diminished accommodation demand for housing, or both. Conversely, a decrease in the vacancy may indicate a surge in net housing demand for accommodation, thereby exerting upward pressure on property prices.

By leveraging a panel analysis on a unique dataset from Hong Kong, this study advances our understanding of the housing vacancy - price relationship. The approach allows for a more accurate assessment of temporal trends, addressing the limitations of previous cross-sectional studies. The findings contribute to both academic research and practical applications in the real estate market, emphasising the importance of considering temporal interactions between housing demand and supply attributes in housing market analyses.

The previous lack of use of the housing vacancy variable as a determinant of housing prices could have arguably occurred due to its data unavailability. Currently, vacancy data is surveyed once every census, and different countries define housing vacancy differently. Hence the digitalisation of utility meters presents a transformative opportunity to modernise vacancy data collection for housing price analysis. Utilising data gathered from digital electricity and water meters, establishing a standardised definition for vacant properties, and collecting real-time vacancy information can help to address the constraints posed by conventional vacancy surveys.

Researchers can incorporate vacancy data more frequently as an important explanatory variable in econometric models of housing prices, providing insights into the relationship between housing supply and demand dynamics. By leveraging real-time vacancy data, policymakers can develop more effective strategies to address housing market imbalances and promote housing affordability. Furthermore, the standardised nature of vacancy data collected through digital utility meters facilitates cross-city and cross-country comparisons, enabling researchers to identify trends and best practices in housing market regulation and policy implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.-Y.Y.; methodology, C.-Y.Y.; software, C.-Y.Y.; validation, T.M. and C.-Y.Y.; formal analysis, C.-Y.Y.; investigation, T.M. and C.-Y.Y.; resources, C.-Y.Y.; data curation, T.M. and C.-Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, T.M. and C.-Y.Y.; project administration, C.-Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets used in this study are publicly available. They can be found at RVD (2024) and C&SD (2024).

Acknowledgments

The project is financially supported by the University of Auckland Faculty Research Development Fund (Ref no: 3729664),

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Belke, A. & Keil, J. (2017). Fundamental determinants of real estate prices: A panel study of German regions, Ruhr Economic Papers, №731, ISBN 978–3–86788–851–6, RWI — Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, Essen. [CrossRef]

- C&SD (2024). Statistics by subject. Census and Statistics Department, HKSAR Government. Available online: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/page_8000.html. Accessed on 18 January 2024.

- Dröes, M.I. & van de Minne, A. (2017). Do the Determinants of House Prices Change over Time? Evidence from 200 Years of Transactions Data, American Economic Association. https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2017/preliminary/paper/7NHnQiSz.

- Égert, B. & Mihaljek, D. (2007). Determinants of house prices in central and eastern Europe, BIS Working Papers no. 236, https://www.bis.org/publ/work236.pdf.

- Feng, Y. Examining the determinants of housing prices and the influence of the spatial–temporal interaction effect: The case of China during 2003–2016. Chinese Journal of Population, Resources and Environment 2020, 18, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, N. (2018). Fundamental Drivers of House Prices in Advanced Economies, IMF Working Paper, WP/18/164.

- Glindro, E.T.; Subhanij, T.; Szeto, J.; Zhu, H. Determinants of house prices in nine Asia-Pacific economies. In Research and Policy Analysis; Bank for International Settlements: Basel, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lerbs, O. and Teske, M. (2016). The House Price-Vacancy Curve, Discussion Paper No. 16-082, Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW). Available online at http://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/dp/dp16082.pdf. Retrieved on 18 January 2024.

- Newing, A.; Hibbert, O.; Van-Alwon, J.; Ellaway, S.; Smith, A. Smart water metering as a non-invasive tool to infer dwelling type and occupancy – Implications for the collection of neighbourhood-level housing and tourism statistics. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2023, 105, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, R.; Gharipour, A.; Fleury, M.; Akpan, I.J. Occupancy detection of residential buildings using smart meter data: A large-scale study. Energy and Buildings, 2019, 183, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RVD (2024) Property Market Statistics, Publications. Rating and Valuation Department, HKSAR Government. Available online: https://www.rvd.gov.hk/en/publications/property_market_statistics.html. Accessed on 18 January 2024.

- Sirman, G. The Value of Housing Characteristics: A Meta Analysis. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 2006, 33, 215-240. Taghizadeh-Hesary, F., Yoshino, N. & Chiu, A. (2019). Internal and External Determinants of Housing Price Booms in Hong Kong, China, ADBI Working Paper Series, № 948, May. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/503436/adbi-wp948.pdf.

- Wheaton, W.C. Vacancy, Search, and Prices in a Housing Market Matching Model. Journal of Political Economy 1990, 98, 1270–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. & Tang, B. On the Determinants of UK House Prices. International Journal of Economic Research 2014, 5, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yiu, C.Y. Why House Prices Increase in the COVID-19 Recession: A Five-Country Empirical Study on the Real Interest Rate Hypothesis. Urban Science 2021, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).