Submitted:

22 February 2024

Posted:

22 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.1. Materials

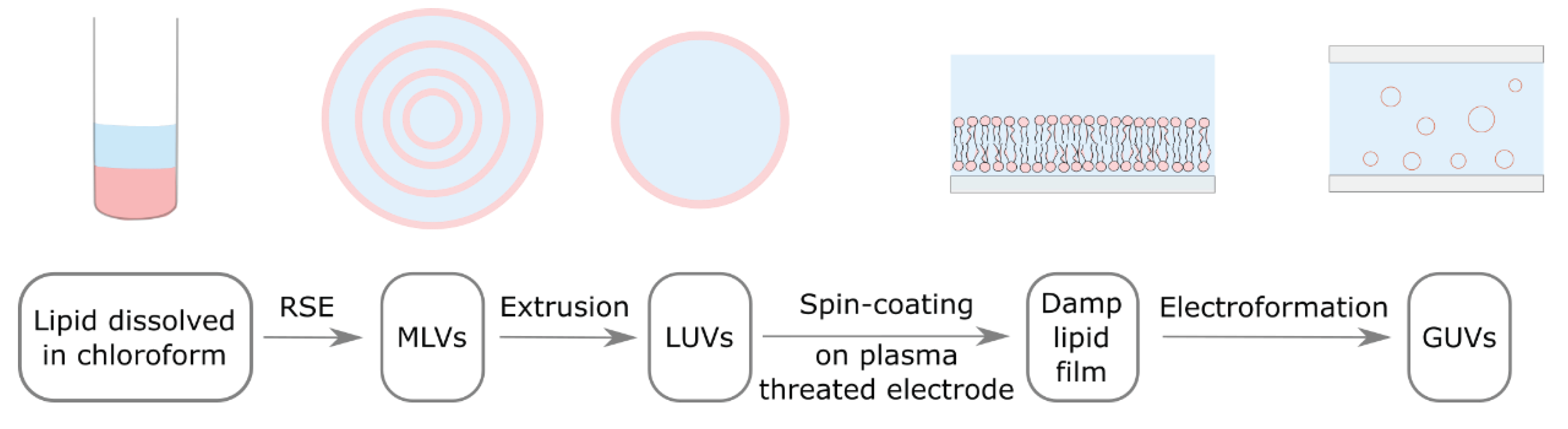

2.2. Preparation of Multilamellar Vesicels Using the Rapid Solvent Exchange Method

2.3. Preparation of Large Unilamellar Vesicles

2.4. Preparation of the Damp Lipid Film

2.5. Electroformation Protocol

2.6. Dynamic light scattering

2.7. Fluorescence Imaging and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Optimization of the protocol

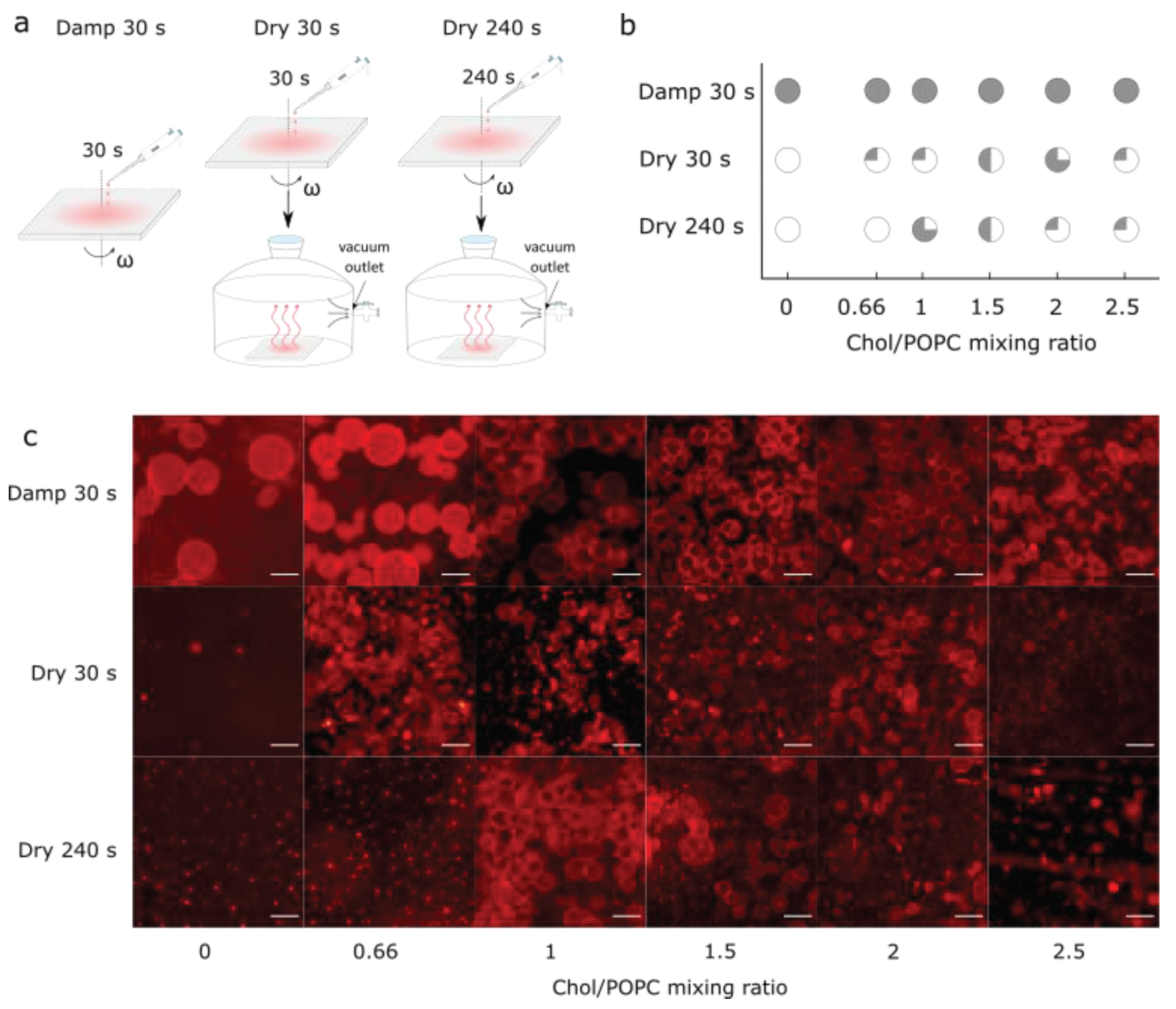

3.1.1. The spin-coating duration for formation of damp lipid film

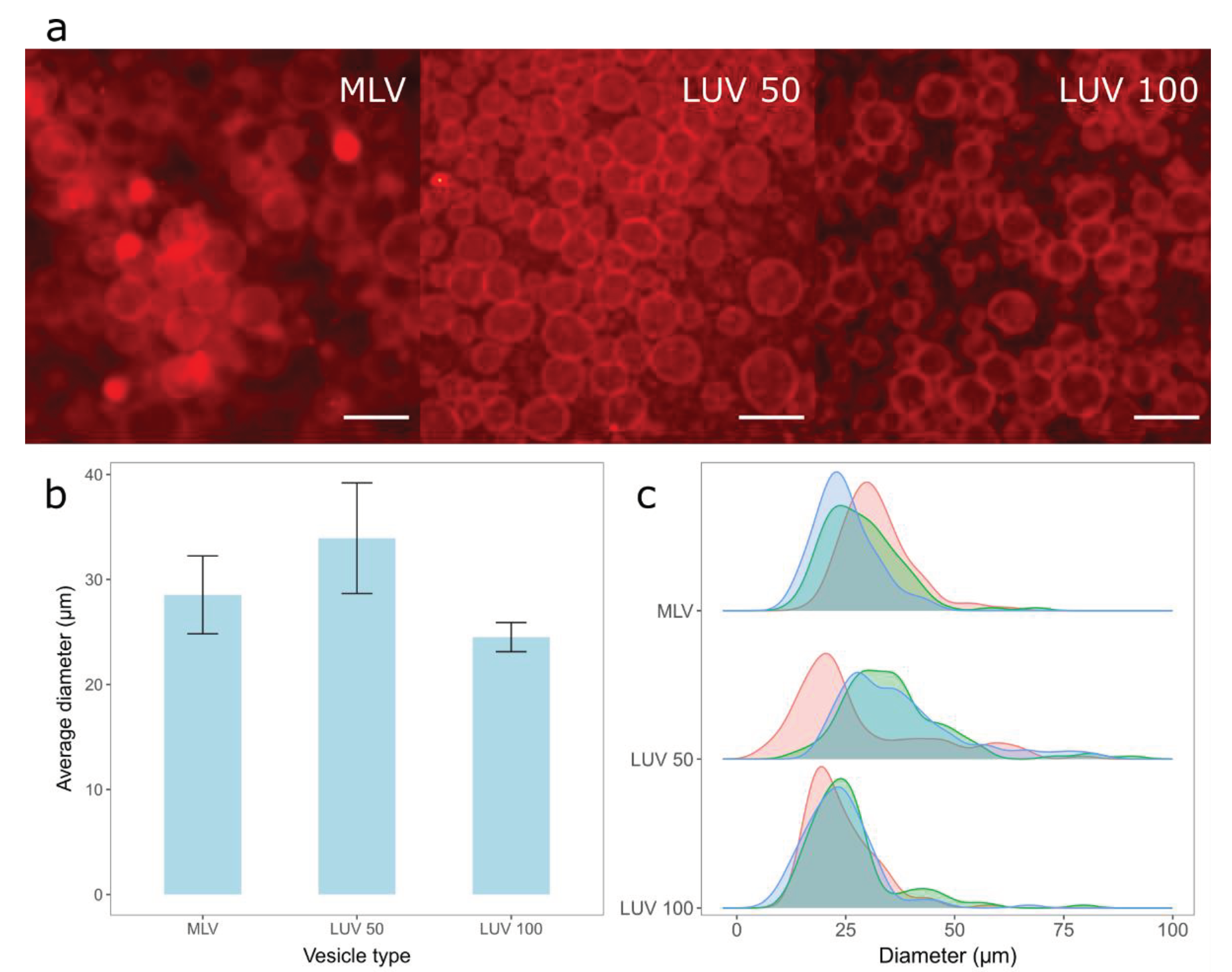

3.1.2. Comparison of the MLVs and LUVs Deposition on the Electrode

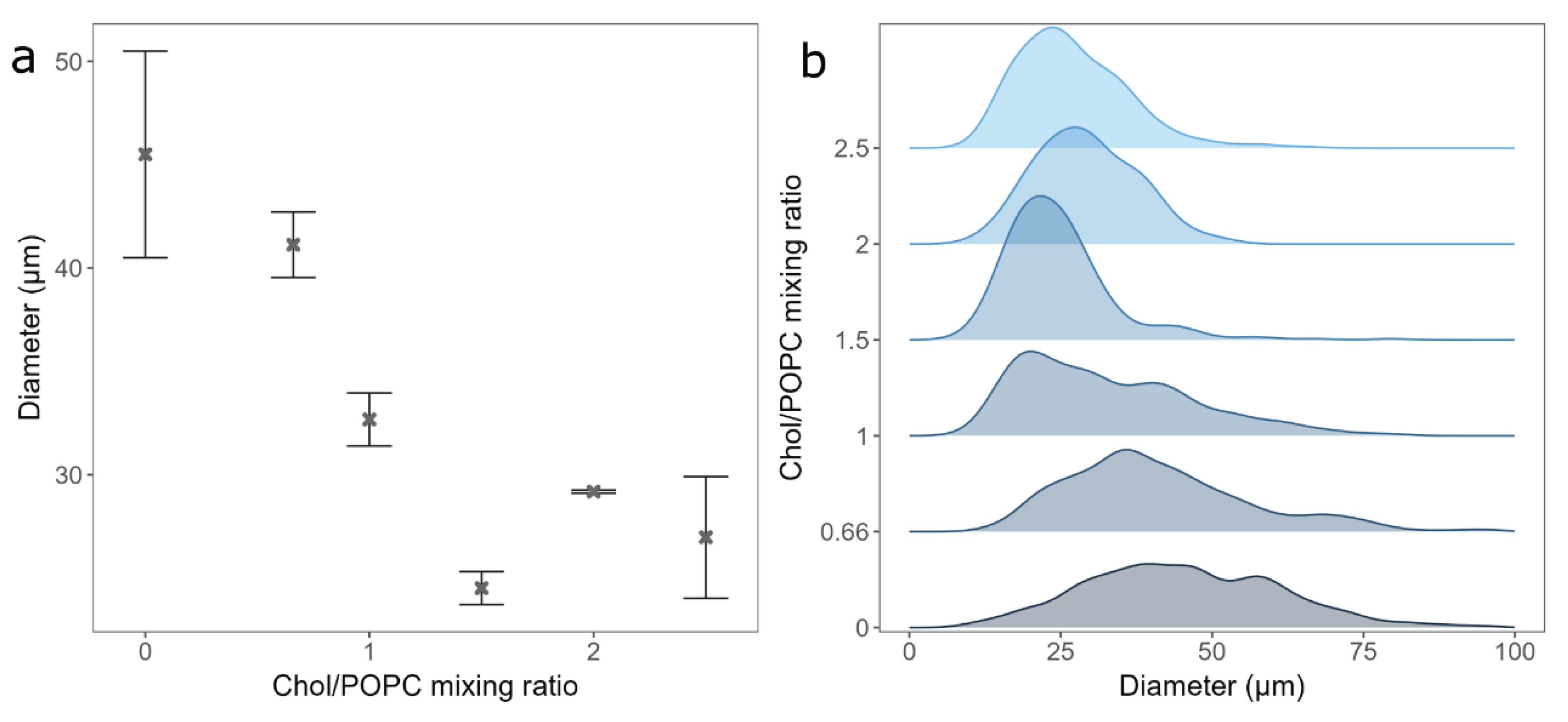

3.2. The Effect of Chol Content

3.3. Comparison with Samples Obtained from Completely Dry Lipid Films

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ertel, A.; Marangoni, A.G.; Marsh, J.; Hallett, F.R.; Wood, J.M. Mechanical Properties of Vesicles. I. Coordinated Analysis of Osmotic Swelling and Lysis. Biophys. J. 1993, 64, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J.P.; Dowben, R.M. Formation and Properties of Thin-Walled Phospholipid Vesicles. J. Cell. Physiol. 1969, 73, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykal-Caglar, E.; Hassan-Zadeh, E.; Saremi, B.; Huang, J. Preparation of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles from Damp Lipid Film for Better Lipid Compositional Uniformity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2012, 1818, 2598–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, T.K.; Cárdenas, M. Understanding the Formation of Supported Lipid Bilayers via Vesicle Fusion—A Case That Exemplifies the Need for the Complementary Method Approach (Review). Biointerphases 2016, 11, 020801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, N.; Pincet, F.; Cribier, S. Giant Vesicles Formed by Gentle Hydration and Electroformation: A Comparison by Fluorescence Microscopy. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2005, 42, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelova, M.I.; Dimitrov, D.S. Liposome Electro Formation. Faraday discussions of the Chemical Society 1986, 81, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.S.; Angelova, M.I. Lipid Swelling and Liposome Formation on Solid Surfaces in External Electric Fields. In New Trends in Colloid Science; Steinkopff: Darmstadt, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Boban, Z.; Mardešić, I.; Subczynski, W.K.; Raguz, M. Giant Unilamellar Vesicle Electroformation: What to Use, What to Avoid, and How to Quantify the Results. Membranes 2021, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veatch, S.L. Electro-Formation and Fluorescence Microscopy of Giant Vesicles With Coexisting Liquid Phases. In; 2007; Vol. 398, pp. 59–72.

- Morales-Penningston, N.F.; Wu, J.; Farkas, E.R.; Goh, S.L.; Konyakhina, T.M.; Zheng, J.Y.; Webb, W.W.; Feigenson, G.W. GUV Preparation and Imaging: Minimizing Artifacts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 2010, 1798, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pott, T.; Bouvrais, H.; Méléard, P. Giant Unilamellar Vesicle Formation under Physiologically Relevant Conditions. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2008, 154, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, P.; Pécréaux, J.; Lenoir, G.; Falson, P.; Rigaud, J.L.; Bassereau, P. A New Method for the Reconstitution of Membrane Proteins into Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. Biophys. J. 2004, 87, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, A.; Jablonski, L.; Jahn, R. A Convenient Protocol for Generating Giant Unilamellar Vesicles Containing SNARE Proteins Using Electroformation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oropeza-Guzman, E.; Riós-Ramírez, M.; Ruiz-Suárez, J.C. Leveraging the Coffee Ring Effect for a Defect-Free Electroformation of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. Langmuir 2019, 35, 16528–16535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, D.J.; Mayer, M. Electroformation of Giant Liposomes from Spin-Coated Films of Lipids. 2005, 42, 115–123. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2005, 42, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Berre, M.; Chen, Y.; Baigl, D. From Convective Assembly to Landau−Levich Deposition of Multilayered Phospholipid Films of Controlled Thickness. Langmuir 2009, 25, 2554–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boban, Z.; Puljas, A.; Kovač, D.; Subczynski, W.K.; Raguz, M. Effect of Electrical Parameters and Cholesterol Concentration on Giant Unilamellar Vesicles Electroformation. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 78, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boban, Z.; Mardešić, I.; Subczynski, W.K.; Jozić, D.; Raguz, M. Optimization of Giant Unilamellar Vesicle Electroformation for Phosphatidylcholine/Sphingomyelin/Cholesterol Ternary Mixtures. Membranes (Basel). 2022, 12, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politano, T.J.; Froude, V.E.; Jing, B.; Zhu, Y. AC-Electric Field Dependent Electroformation of Giant Lipid Vesicles. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2010, 79, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billerit, C.; Jeffries, G.D.M.; Orwar, O.; Jesorka, A. Formation of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles from Spin-Coated Lipid Films by Localized IR Heating. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 10823–10826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguz, M.; Kumar, S.N.; Zareba, M.; Ilic, N.; Mainali, L.; Subczynski, W.K. Confocal Microscopy Confirmed That in Phosphatidylcholine Giant Unilamellar Vesicles with Very High Cholesterol Content Pure Cholesterol Bilayer Domains Form. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 77, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buboltz, J.T.; Feigenson, G.W. A Novel Strategy for the Preparation of Liposomes : Rapid Solvent Exchange. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 1999, 1417, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buboltz, J.T. A More Efficient Device for Preparing Model-Membrane Liposomes by the Rapid Solvent Exchange Method. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2009, 80, 124301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X. Electroformation of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles in Saline Solution. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2016, 147, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boban, Z.; Mardešić, I.; Jozić, S.P.; Šumanovac, J.; Subczynski, W.K.; Raguz, M. Electroformation of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles from Damp Lipid Films Formed by Vesicle Fusion. Membranes 2023, 13, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, E.; Frey, S.; Tamm, L.K. Formation of Supported Planar Bilayers by Fusion of Vesicles to Supported Phospholipid Monolayers. BBA - Biomembr. 1992, 1103, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, T.K.; Cárdenas, M. Understanding the Formation of Supported Lipid Bilayers via Vesicle Fusion—A Case That Exemplifies the Need for the Complementary Method Approach (Review). Biointerphases 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaei, S.R.; Jackman, J.A.; Kim, M.; Yorulmaz, S.; Vafaei, S.; Cho, N.J. Biomembrane Fabrication by the Solvent-Assisted Lipid Bilayer (SALB) Method. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 2015, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, L.; Raguz, M.; Subczynski, W.K. Formation of Cholesterol Bilayer Domains Precedes Formation of Cholesterol Crystals in Cholesterol/Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine Membranes: EPR and DSC Studies. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 8994–9003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguz, M.; Mainali, L.; Widomska, J.; Subczynski, W.K. The Immiscible Cholesterol Bilayer Domain Exists as an Integral Part of Phospholipid Bilayer Membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2011, 1808, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguz, M.; Mainali, L.; O’Brien, W.J.; Subczynski, W.K. Lipid Domains in Intact Fiber-Cell Plasma Membranes Isolated from Cortical and Nuclear Regions of Human Eye Lenses of Donors from Different Age Groups. Exp. Eye Res. 2015, 132, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulenko, T.N.; Chen, M.; Mason, P.E.; Mason, R.P. Physical Effects of Cholesterol on Arterial Smooth Muscle Membranes: Evidence of Immiscible Cholesterol Domains and Alterations in Bilayer Width during Atherogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 1998, 39, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herold, C.; Chwastek, G.; Schwille, P.; Petrov, E.P. Efficient Electroformation of Supergiant Unilamellar Vesicles Containing Cationic Lipids on ITO-Coated Electrodes. Langmuir 2012, 28, 5518–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Development Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, R.P.; Bérat, R.; Brisson, A.R. Formation of Solid-Supported Lipid Bilayers: An Integrated View. Langmuir 2006, 22, 3497–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, T.K.; Cárdenas, M.; Wacklin, H.P. Formation of Supported Lipid Bilayers by Vesicle Fusion: Effect of Deposition Temperature. Langmuir 2014, 30, 7259–7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Trefna, H.; Persson, M.; Kasemo, B.; Svedhem, S. Formation of Supported Lipid Bilayers on Silica: Relation to Lipid Phase Transition Temperature and Liposome Size. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).