1. Introduction

Non-destructive testing (NDT) plays a crucial role in ensuring the safety and reliability of engineering structures across various sectors, including automotive, aerospace, and civil engineering. A critical component in the railway system is the railway track, which is susceptible to various types of cracks. Current standards for railway inspection predominantly rely on visual testing (VT) methods, which are time-consuming, qualitative, and the VT remain limited by top surface inspection and the need for expertise. Monitoring surface and sub-surface defects, including burns, squat-like rail cracks, and others type of local damages costs for the millions of pounds every year in U.K. [

1] railway inspection and capability of real-time inspection of these defects presents significant challenges, with only a limited array of NDT techniques available. Among these, Ultrasonic Testing (UT) is frequently utilized due to its ability to penetrate the bulk material of the track. However, this technique encounters a notable limitation in identifying both surface and subsurface anomalies [

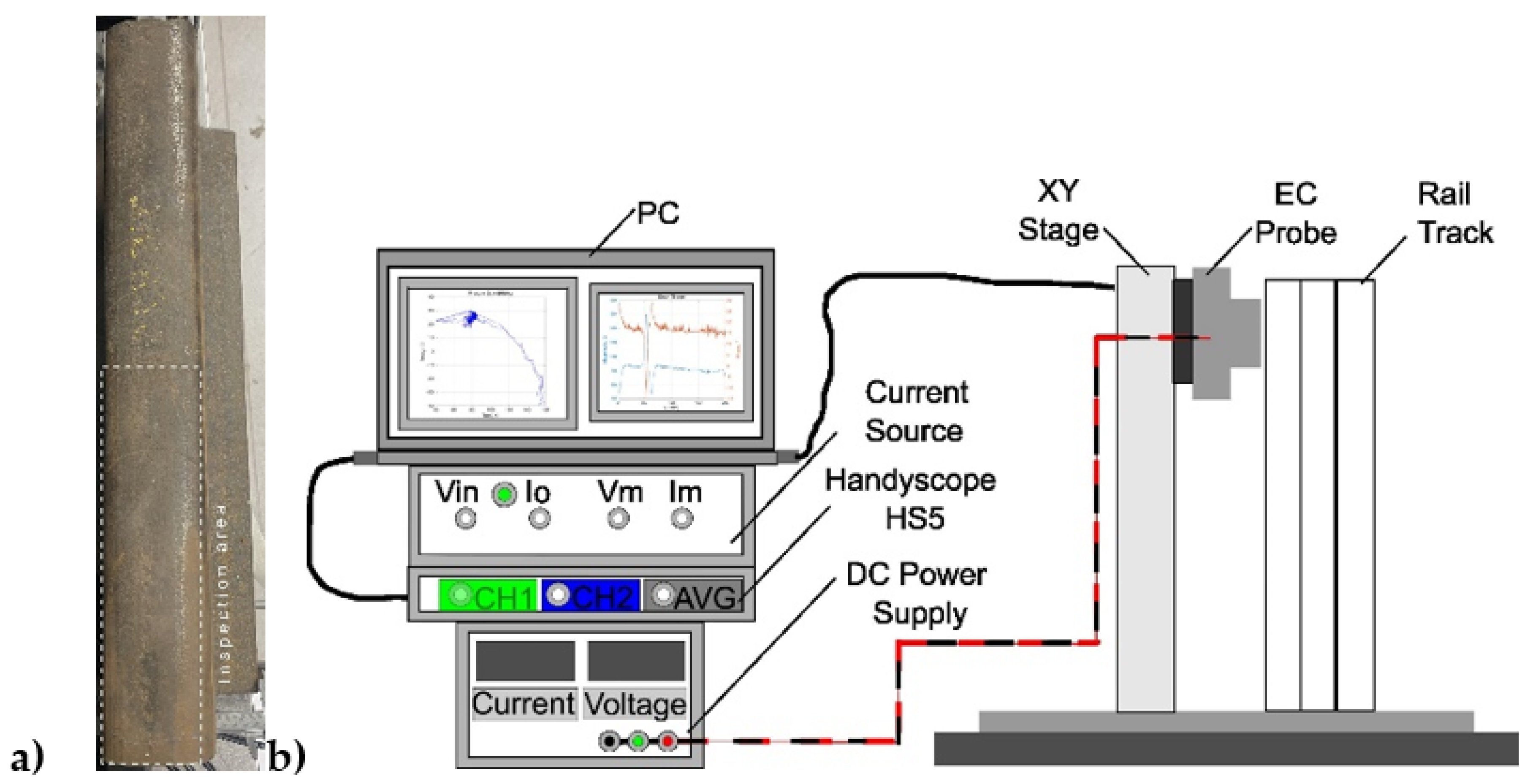

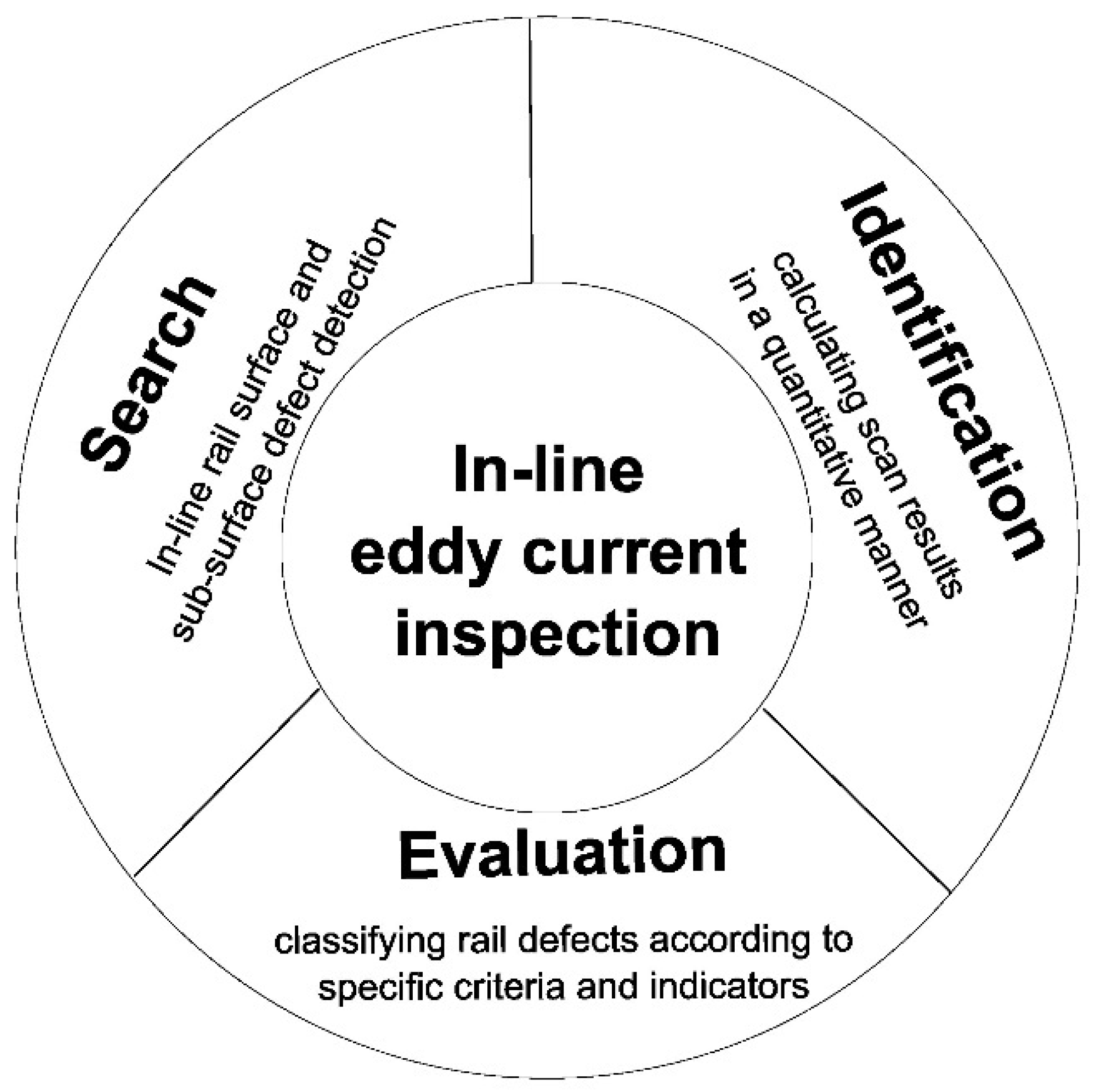

2]. While it is possible to detect surface imperfections through the reflective echoes of ultrasonic waves once they reach a particular size, UT is not capable of assessing the extent of these defects nor can it differentiate among various defect categories. Thus, there is an urgent need for a more efficient and reliable surface and sub-surface inspection method to ensure structural integrity of rail tracks. Consequently, Eddy Current Testing (ECT) has been identified as an appropriate NDT technique for in-line railway inspection. To realize this application and facilitate full automation of the inspection process, the integration of various distinct technologies is imperative. This integration is essential to address the complex requirements of real-time, efficient, and accurate railway inspection. This project aims to substantially enhance the efficiency of real-time railroad inspection, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The primary challenge in measurements of this nature is not inherently linked to the limitations of sensor technology but rather pertains to the management and processing of the data collected [

3]. There were many attempts to embed the similar ECT systems for online detection and location of rails defects published before [

4,

5,

6]. However, the lack of available EC probe optimization studies for real-time inspection [

7] of rail tracks motivated to current project. Specific online data processing algorithm is provided to manage with the huge amount of data effectively associated with the nature of this type of inspection. During each inspection, the system aboard the train accumulates a substantial volume of data, within which only a fraction is of significant relevance. Identifying and extracting these pertinent data segments is crucial for determining their precise locations along the track. Typically, specialized research groups are dedicated to the management of such data, employing strategies that involve either transmitting the data for remote analysis or conducting local analysis onboard to detect anomalies that surpass predefined thresholds. Despite the fact that based on the proposed improved system as is shown in

Figure 1 this project needs to characterize the different types of actual types of railroads damages this initial research is limited to search and identification parts.

This initial research aims to optimize the proposed ECT probe designs to develop inspection system integrated within train systems, capable for a real-time inspection in dynamic conditions. Further studies will be more focused on investigation the characterization of localized rail track defects, particularly quats. The goal is to optimize the sensor design, enhancing its sensitivity to these specific defects under varying inspection conditions, including factors like speed and vibration. In response to these operational challenges, the study has developed a new hybrid ECT probe, tailored to fulfill the unique requirements of real-time, accurate rail track inspection.

A substantial body of research has been dedicated to the optimization of eddy current probes, with various studies focusing on enhancing their efficacy in diverse applications. In an exploration of the efficacy of ECT for in-plane fiber waviness detection in unidirectional carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP), [

8] employed a diverse set of probes: circular driving, symmetrical driving, and uniform driving. This study is distinguished by its methodical comparative analysis and the integration of sophisticated image processing techniques, including the Canny filter and Hough transform, to ascertain the probes’ precision and accuracy against X-ray CT imaging benchmarks. The research notably identifies the uniform driving probe as superior in accurately detecting fiber waviness angles above 2° in unidirectional CFRP, evidenced by a root mean square error of 1.90° and a standard deviation of 4.49°. However, the study’s applicability may be constrained by its focused examination of specific waviness angles and CFRP types.

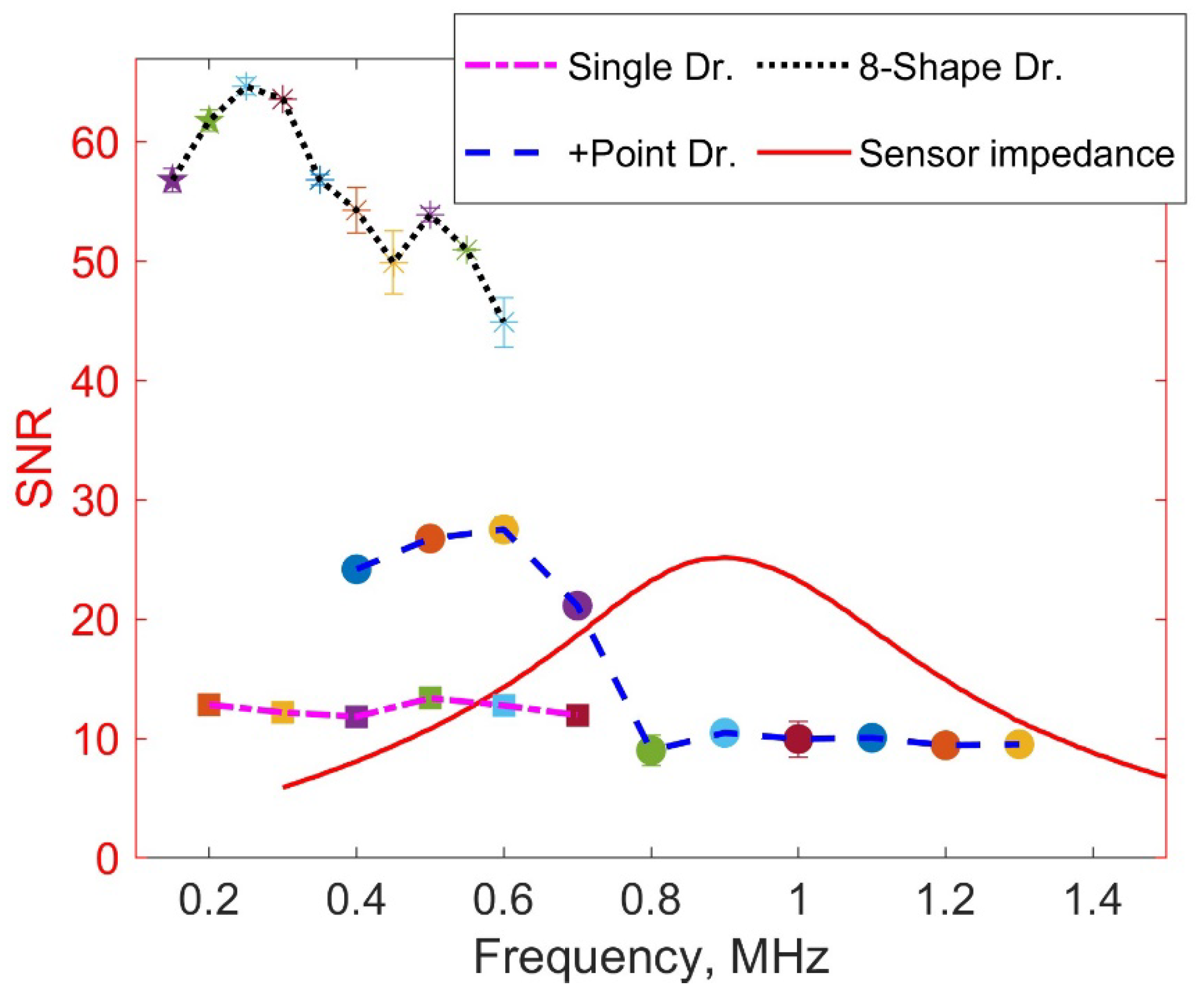

Expanding on ECT probe optimization, [

9] investigates the Near Electrical Resonance Signal Enhancement (NERSE) phenomenon. This study reveals that operating an absolute EC probe near its electrical resonance, particularly in the 1 to 5 MHz frequency range, significantly amplifies defect signals in aerospace superalloy Titanium 6Al-4V. The research reports Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) peaks up to 3.7 times higher near resonance frequencies, attributed to defect-induced resonant frequency shifts. This finding posits a straightforward yet efficacious approach to enhancing the sensitivity of standard industrial EC testing through the NERSE frequency band.

The investigation in [

10] introduces a novel sensor design aimed at advancing nondestructive testing methods, with a specific focus on delamination detection in CFRP. Experimental validation on cross-ply CFRP laminates supports the method’s effectiveness, though its broad applicability may be limited by certain conditions and assumptions inherent in the study.

In the realm of real-time EC inspection, [

11] focuses on giant magnetoresistive (GMR) field sensors, juxtaposing finite-element model (FEM) predictions with experimental findings to underscore the development of a swift and flexible inspection system. Concurrently, [

12] details the optimization of a low-frequency EC technique for internal defect detection in steel structures, analyzing a custom-designed magnetic sensor system in tandem with FEM results. This study explores the fine-tuning of probes using magnetoresistive sensors, supported by simulations with CIVA software.

In [

13] delineates the development of a flexible planar EC sensor array, targeting microcrack inspection in critical airplane components. The study details the sensor design, measurement mechanics, and correlates these with FEM outcomes.

In a significant advancement, in [

14] present a differential coupling double-layer coil for eddy current testing, achieving notable improvements in sensitivity and lift-off tolerance. This coil’s innovative double-layer structure and differential coupling energy mechanism demonstrate the potential of strategic coil design and frequency optimization in overcoming traditional limitations of eddy current probe sensitivity, especially in scenarios with high lift-off. An extended literature review about applications and advantages of planar rectangular receiver in ECT provided in this study.

Further progress is reported in [

15], which proposes a novel figure 8-shaped coil for transmitter-receiver (T-R) probes. This unique design effectively counters signal distortion due to lift-off variation and maintains consistent output when aligned with the CFRP’s fiber orientation. The probe is characterized by its insensitivity to lift-off variations and enhanced sensitivity to defects in CFRPs.

Lastly, authors in [

16] present an analytical model for a figure 8-shaped coil comprising two oblique elliptical coils. This model enables the manipulation of the electromagnetic concentrative region and the eddy current density. Adjustments in the elliptical shape or the spread angle between the coils lead to intensified and expanded eddy currents, concentrating under the coil’s symmetric center. This innovative design and analytical methodology significantly elevate the accuracy in detecting conductive material defects, marking a pivotal development in nondestructive testing methods.

While each study substantially enriches the field of ECT probe optimization and nondestructive testing, their practical application varies based on specific conditions, material types, and defect characteristics. These advancements lay the groundwork for exploring the applicability of novel EC probes in railroad inspection.

The objective of this paper is the development of ECT sensors tailored for real-time surface inspection of rail tracks, exploring design parameters of a novel directional ECT probe for detecting surface-breaking cracks and common railway flaws. This research, aimed at optimizing eddy current probes presented in [

17], seeks to significantly enhance real-time inspection effectiveness, potentially marking a breakthrough in railroad inspection methodologies.

2. Methodology

The development of the proposed inspection system, as depicted in

Figure 1, necessitates comprehensive studies to verify the feasibility and reliability of integrating the probe into the inspection train. This integration must account for variations in speed and vibrations from both the train and rail tracks, necessitating probe optimization. However, the current experimental setup is primarily aimed at optimizing the probe design for heightened sensitivity to common defects in ferromagnetic materials, rather than replicating the exact operational environment.

The directional probe design previously outlined in references [

8] has not yet been tested on metallic components. Studies in [

8,

17,

18] have demonstrated optimum sensitivity beyond the receiver’s resonance for CFRP materials, which now requires validation for ferromagnetic materials. Therefore, our methodology involves multiple studies focusing on real-time eddy current (EC) probe optimization.

This research utilizes the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for quantitative evaluation, comparing the sensitivity of the best probe configuration from earlier research [

17] with the two novel sensor designs proposed in this study. Investigating the optimal frequency is crucial for boosting sensitivity to specific defects. This study delves into the proximity frequency range, resonating the receiver coil to elevate SNR levels. Similar research [

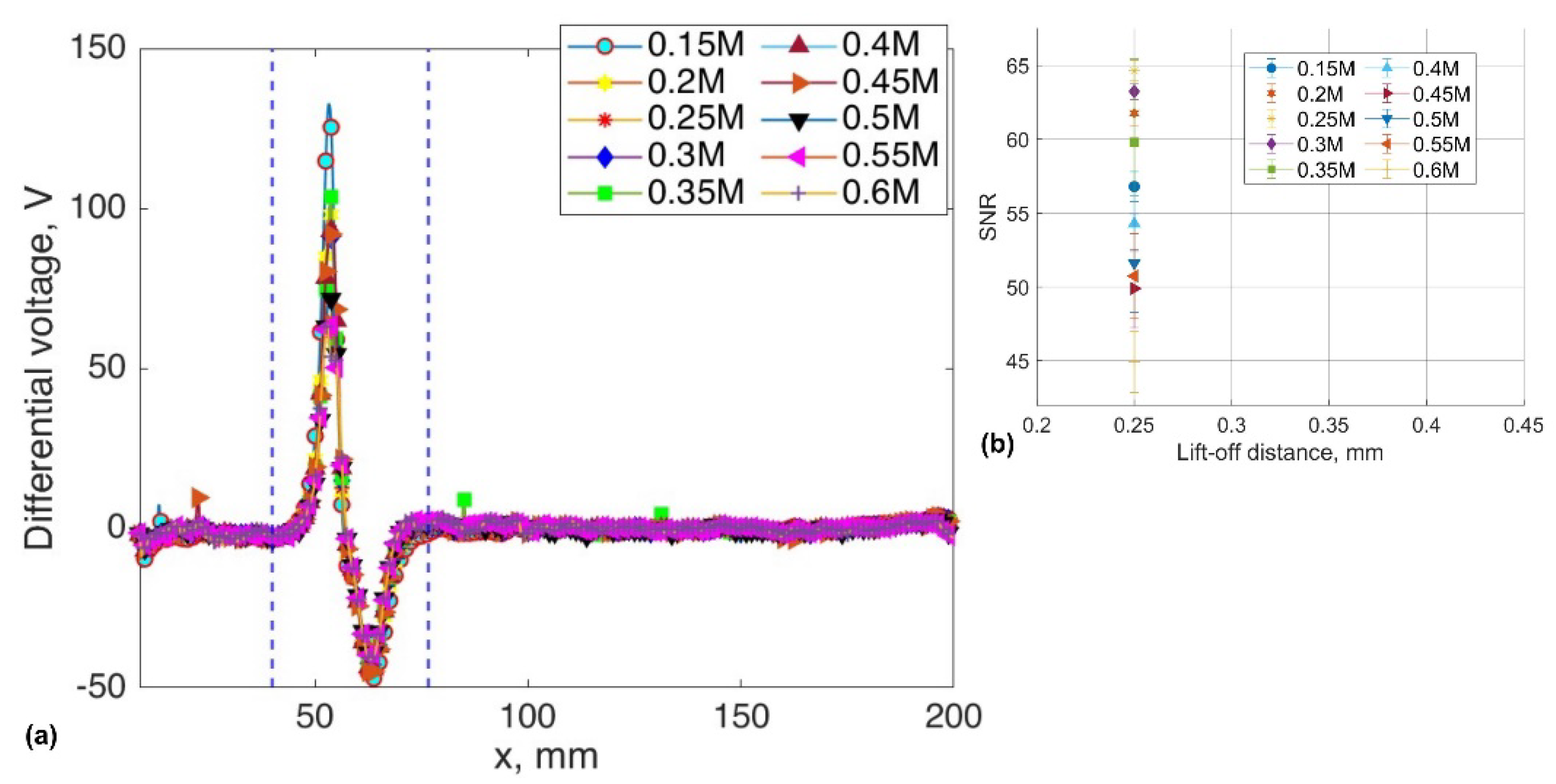

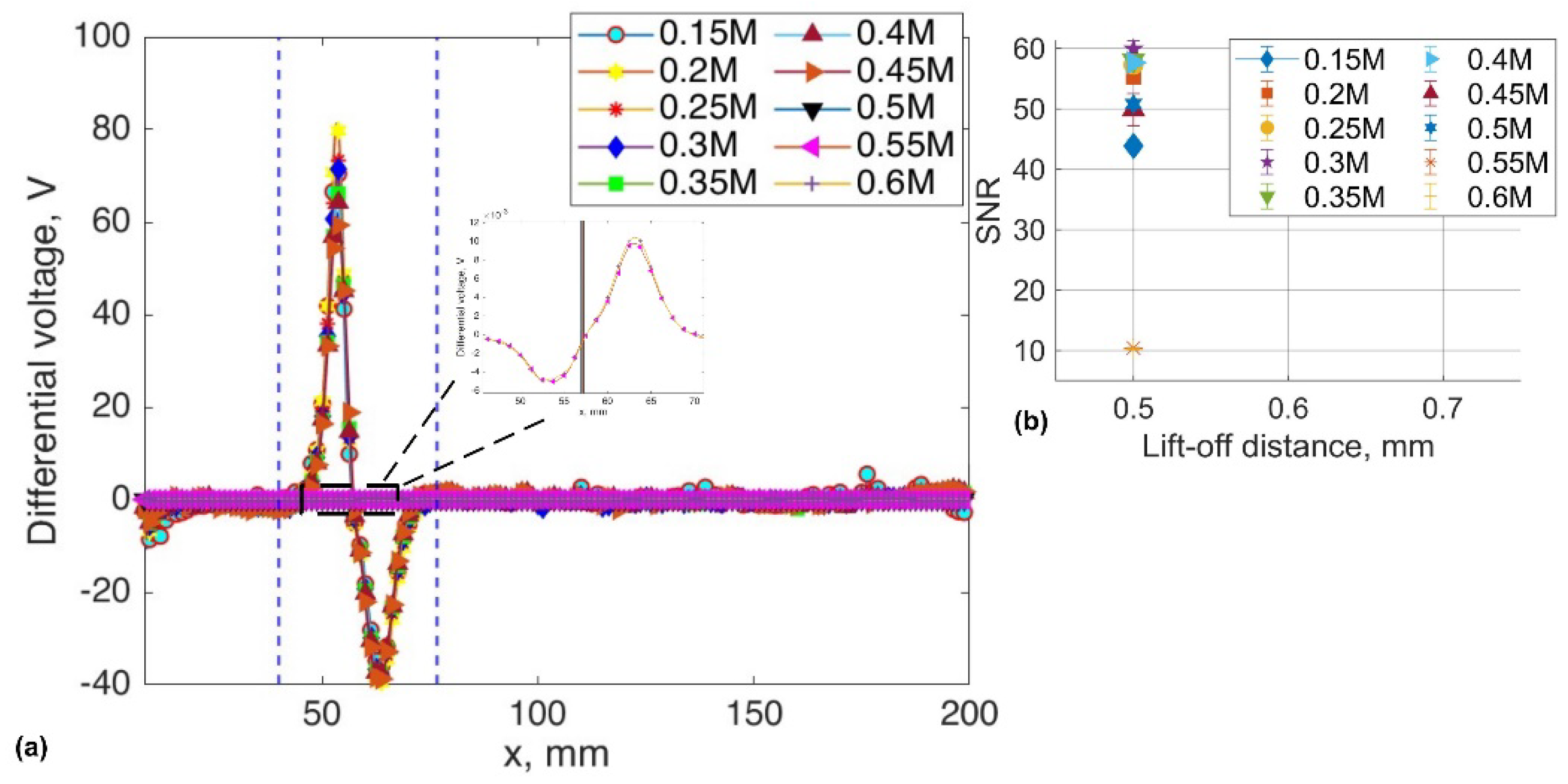

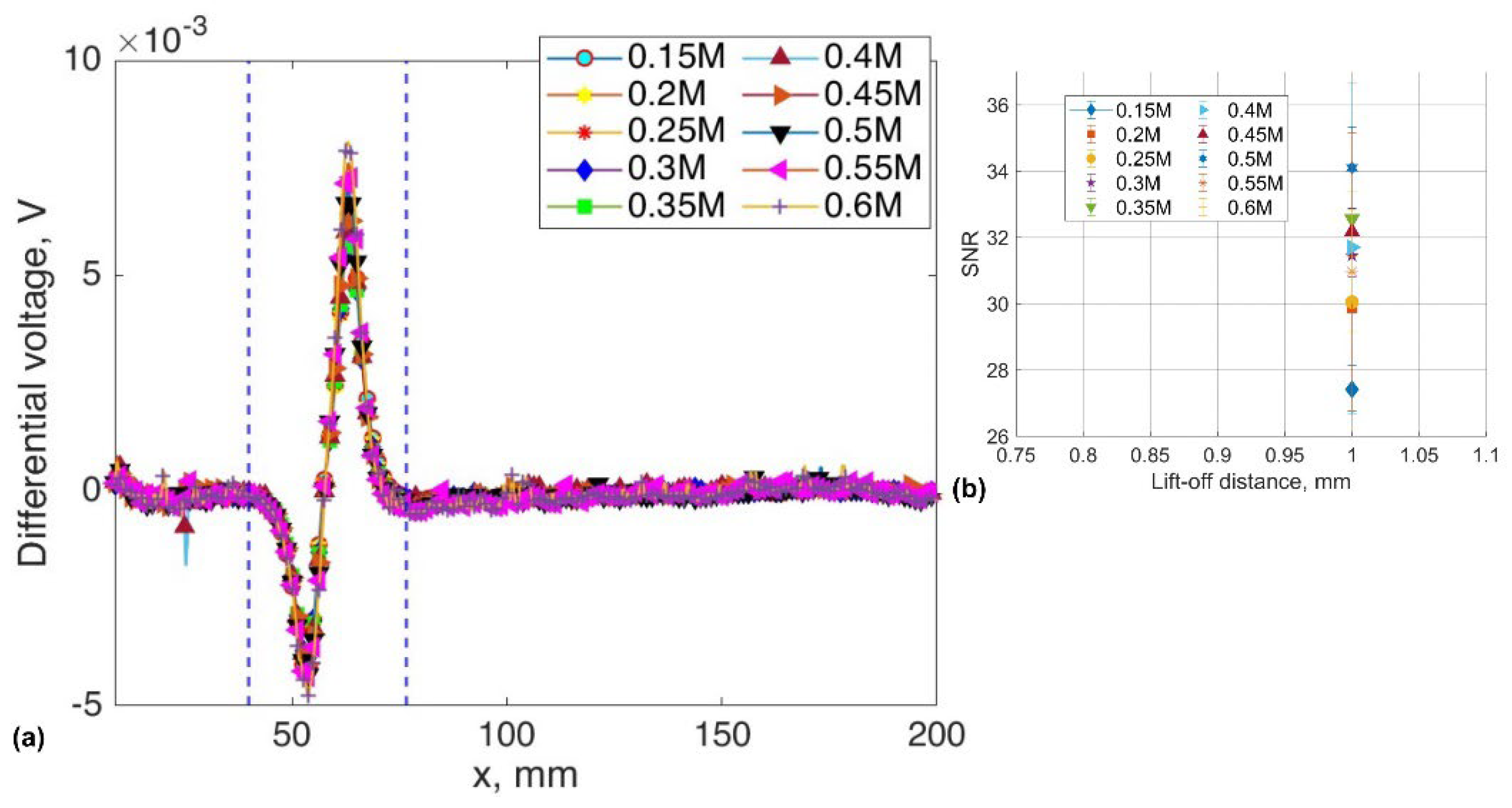

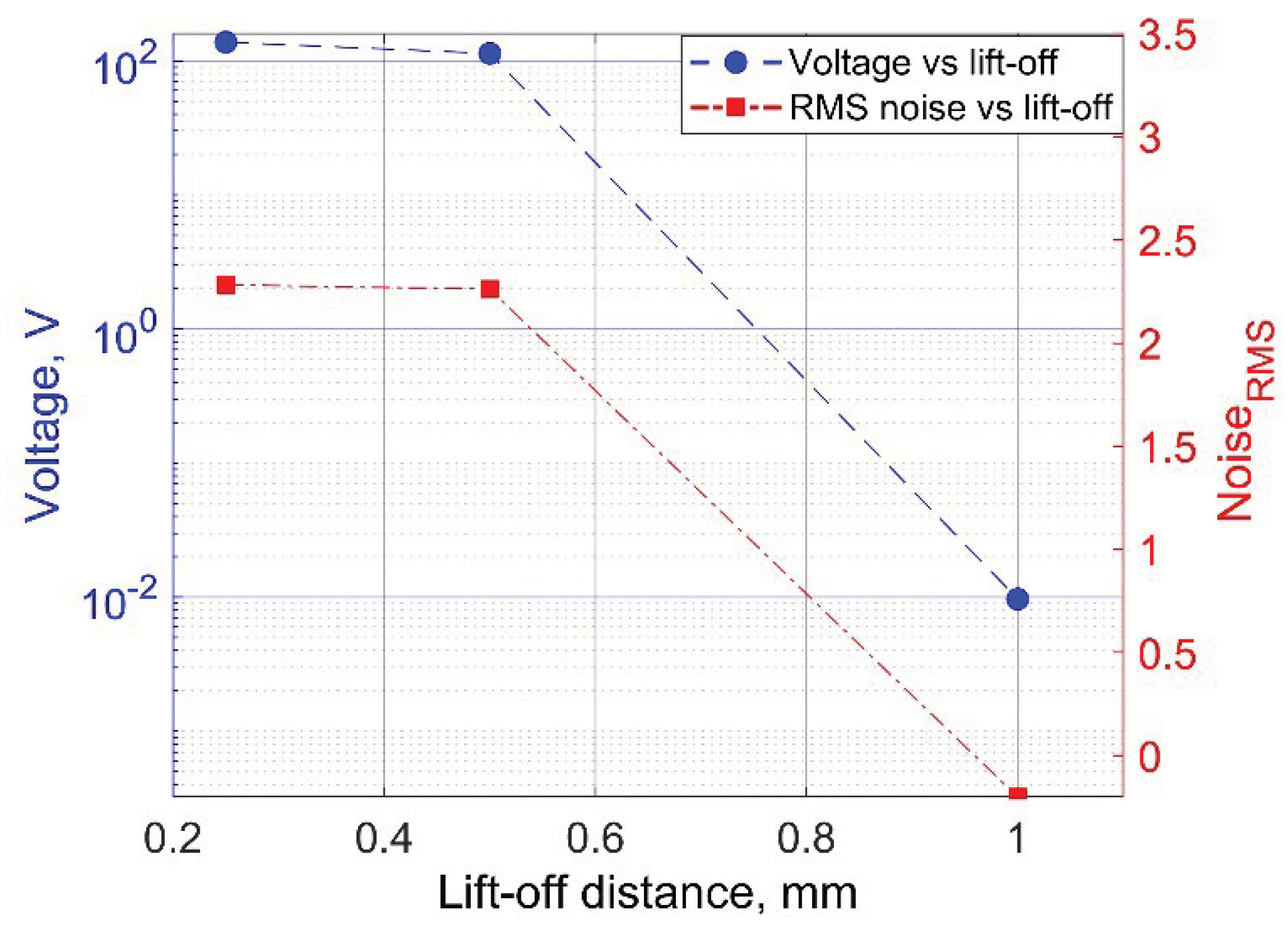

3] analyzed phase shifts with frequency variations to identify the optimal operational frequency, noting that increased phase shifts improve defect depth resolution and decrease detection errors. Another critical aspect of this research is determining the optimal lift-off distance, ranging from 0.25 to 1 mm, as lift-off variation is a key parameter before in-situ inspection. This involves balancing sensitivity against lift-off distance, an essential factor in eddy current probe optimization. Related research [

4] conducted fixed-distance (1 mm) inspections from the rail track surface by integrating EC instrumentation into a grinding train for early detection of surface damages. This highlights the importance of understanding the trade-offs between sensitivity and lift-off distance for effective EC probe deployment in real-world applications.

2.1. Sensor Design

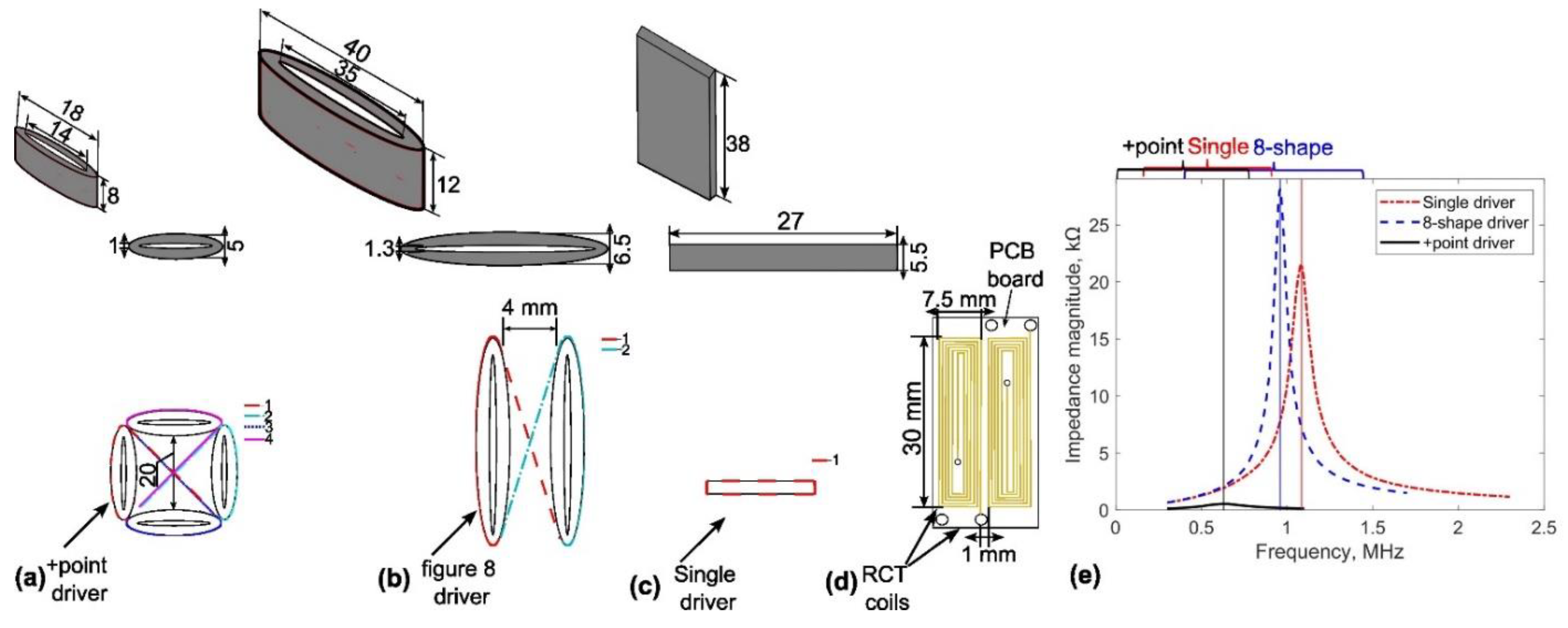

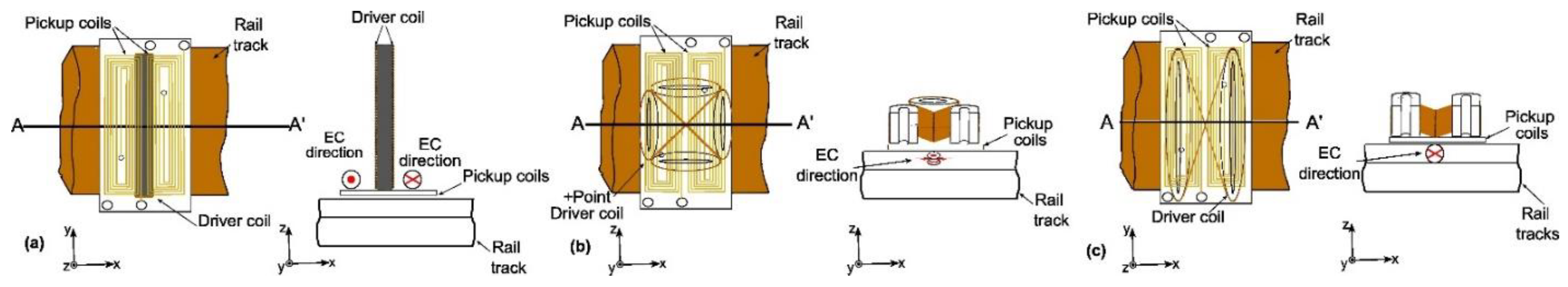

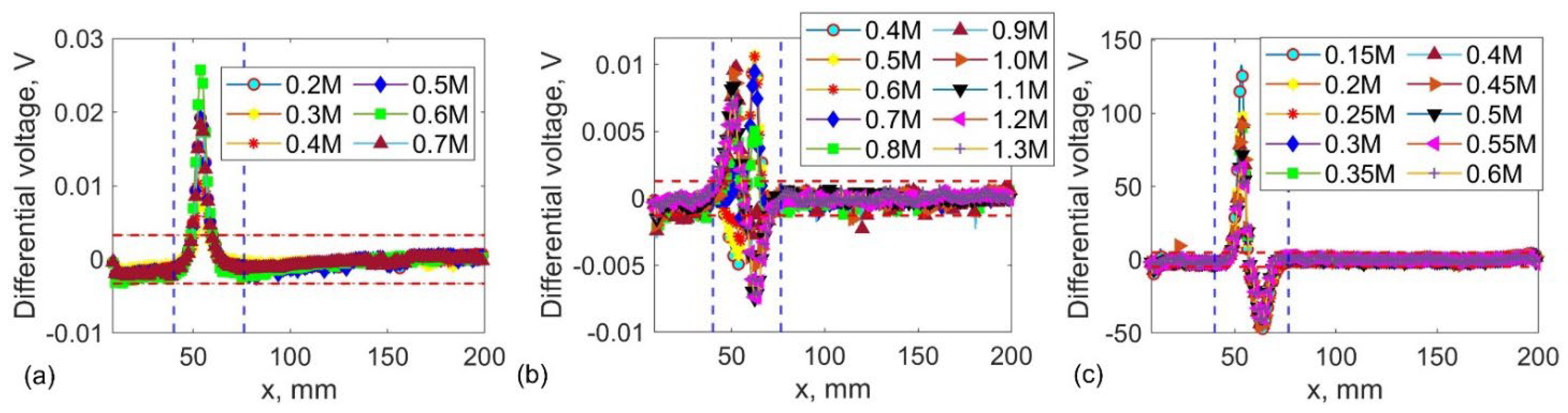

The paper presents a frequency selection study focusing on three sensor designs, depicted in

Figure 2. To minimise the lift off noise differentially winded two adjacent rectangular sensors and to increase the induced eddy currents (ECs) density and concentrative area within the material single driver, special figure 8-shape elliptical and four figure 8-shape (+point) driver coils were designed and manufactured. The initial design utilizes singular excitation driver coils, while subsequent modifications involve altering the aspect ratio of the previous non-uniform configuration [

17], as depicted in

Figure 2(a), tailored for the inspection requirements of railroad infrastructure. Drawing upon principles from eddy current (EC) theory, the inclusion of winding +point [

3] and 8-shape [

15] configurations aims to amplify the sensitivity of pickup signals. However, it is noteworthy that similar driver designs have not been previously manufactured to address the specific needs of the targeted application.

2.2. Driver Coil Design

To optimize performance under the distributed magnetic field of the driver coil, the width of the coil recommended to be equal or exceed the length of the pickup coil. Increasing the number of turns in the driver coil strengthens the magnetic field but raises inductance, consequently lowering resonance frequency. The fabrication of driver coils with 62, 72, and 66 turns on ferrite, corresponding to single, +point, and 8-shape configurations, respectively, ensures the generation of a suitably robust magnetic field to produce the desired excitation frequency signal.

Table 1 provides driver and pickup coils parameters.

Peak frequencies of the driver coil vary based on winding quality and turn count.

Figure 3 shows three driver winding methods along with their dimensions and resonance frequencies. The driver coils’ impedance spectra were assessed employing a Network Analyzer (TE3001, Trewmac Systems, Australia). Resonant frequencies of approximately 1.1, 0.6, and 1 MHz were observed for the single, +point, and figure 8-shape drivers, respectively.

2.3. Planar Rectangular Pickup Coils

The planar rectangular pickup coils advantages and some limitations along with its application challenges is reviewed by study in [

14]. The consistency of detected signals and the flexibility to manufacture with various dimensions to accommodate for different track widths make printed PCB-based technology ideal candidate for manufacturing. The sensor parameters and dimensions are presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 3 respectively.

Figure 3.

Directional EC probe design: (a) winding method of the +Point, (b) figure 8-shape, (c) rectangular single drivers d) rectangular (RCT) pickup coil dimensions (top-down view) and resonant frequencies of different driver coils.

Figure 3.

Directional EC probe design: (a) winding method of the +Point, (b) figure 8-shape, (c) rectangular single drivers d) rectangular (RCT) pickup coil dimensions (top-down view) and resonant frequencies of different driver coils.

2.4. Amplifier

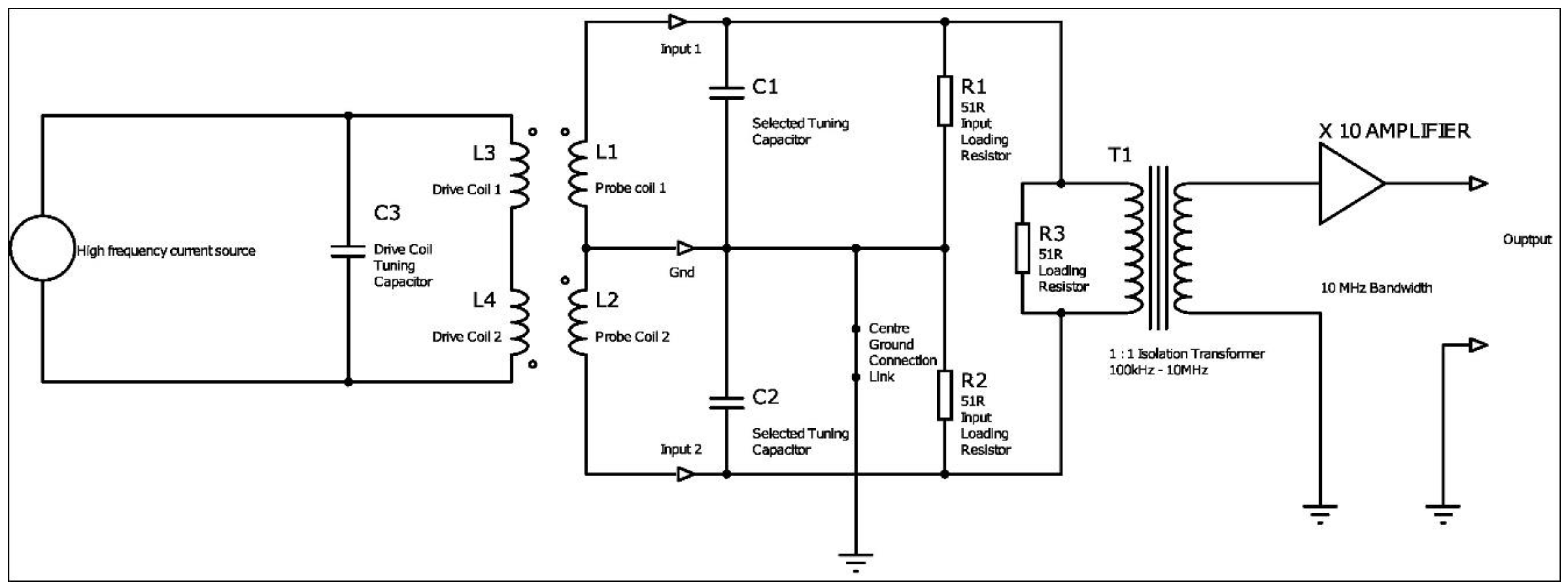

In eddy current testing (ECT) non-destructive evaluation (NDE), limitations arise from noise sources like sample electromagnetic property variations, vibration, temperature changes, and probe lift-off and tilt. Utilizing signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) as a metric for probe performance evaluation is advisable. The low-pass filtering effect of the feedback amplifiers is characterized by the closed-loop bandwidth, which is the unity gain-bandwidth product divided by the closed-loop gain. While further reducing bandwidth at a specific gain value is feasible, it introduces phase lags at target frequencies, impacting gain.

Figure 4 illustrates the fundamental components of the amplifier and the coil input circuits. In the simplified circuit diagram, all external circuitry is situated left of the “Input 1” & “Input 2” terminals, with onboard components to their right. Coils L1 & L2 function as pickup coils, inducing emfs in series opposition, yielding a differential voltage output. L3 and L4, the drive coils, wound in a “figure of eight” pattern around ferrite bar cores, generate opposing AC fields at adjacent poles. The drive coil tuning capacitor, chosen for resonance, amplifies coil currents and voltages, enhancing sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio. The combined output of the pickup coils serves as a differential input signal for the amplifier, connected to Input 1 & 2 terminals. The input circuit features switch-selectable capacitors for coil tuning and various loading resistors, with the option to disconnect the center ground connection. Implementing a non-earth referenced input via a signal isolation transformer is preferred, offering cost-effective common mode rejection. The amplifier circuit, inclusive of the isolation transformer, delivers a gain of 10 (or +20dB) into an infinite resistance load, with a flat frequency response between 100kHz and 2MHz. Beyond 5MHz, gain reduces to 19.3 dB with a 40° phase lag, with a 3dB drop at 11.25MHz. For remote signal transmission, 50 ohm coaxial cable is advised, with a 50 ohm termination for cables longer than approximately 3 meters, typically reducing gain by 6dB. Capacitor switchers were integrated into the amplifier board to adjust the receiver coil’s resonant frequency within a specified range. Equation 1 provides a formula for calculating the required capacitance for desired resonance based on probe coil inductance and target frequency.

where ω₀ = 2πf₀. Here, f₀ represents the desired resonant frequency (1.5 MHz), C is the tuning capacitance in farads, and L denotes the probe inductance (1.0

× 10⁻

⁶ H).

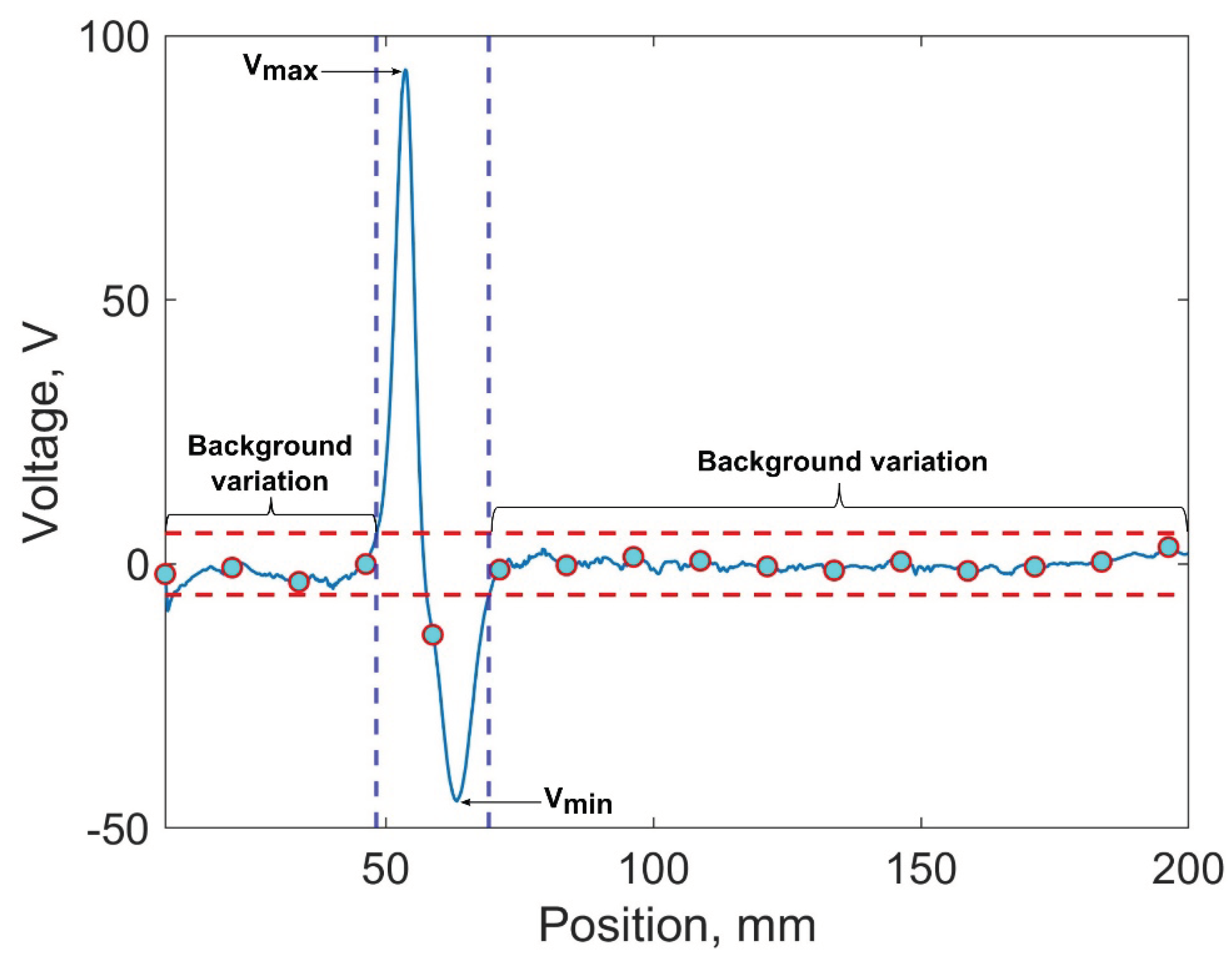

2.5. Methodology for Estimating SNR

The evaluation of three probe design sensitivities and identification section in

Figure 1 is quantitatively assessed using SNR.

Figure 5 depicts the proposed methodology for identification based on a 0.4MHz exemplar sensor signal using an EC probe with a figure 8-shaped driver coil. Data collection begins from 0 to 50 mm over a large non-damaged area of the rail track (as shown in

Figure 5). This data is utilized for automatic calculation of twice the root-mean-squared (RMS) value of background structural noise as a threshold to distinguish sensor signals (indicated by the horizontal dashed line in

Figure 5). Any signal exceeding twice the mean RMS noise voltage is considered a sensor signal and undergoes peak value detection. Upon passing the defective zone, the algorithm automatically provides information about the estimated SNR calculated using the equation: