Submitted:

19 February 2024

Posted:

19 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

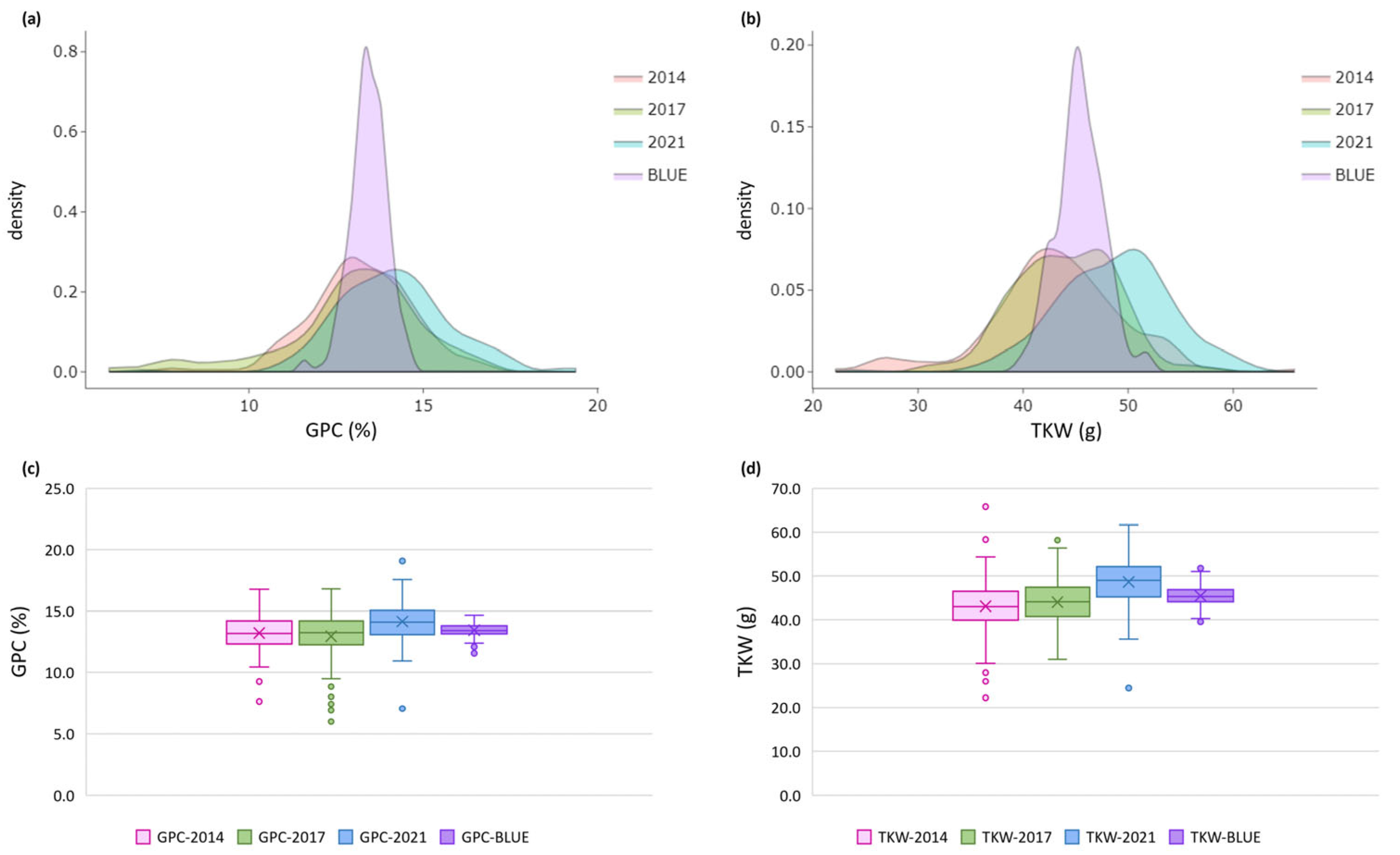

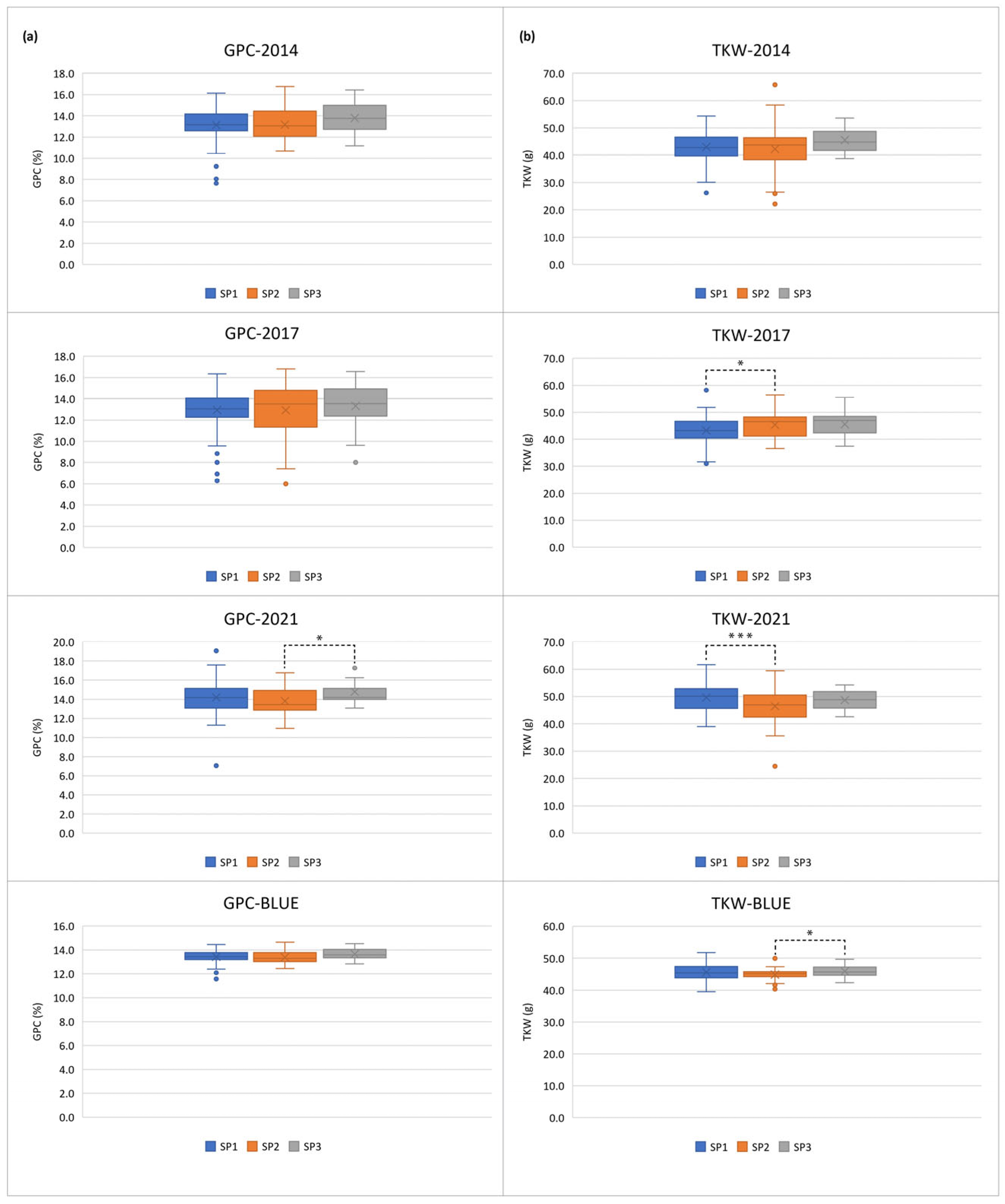

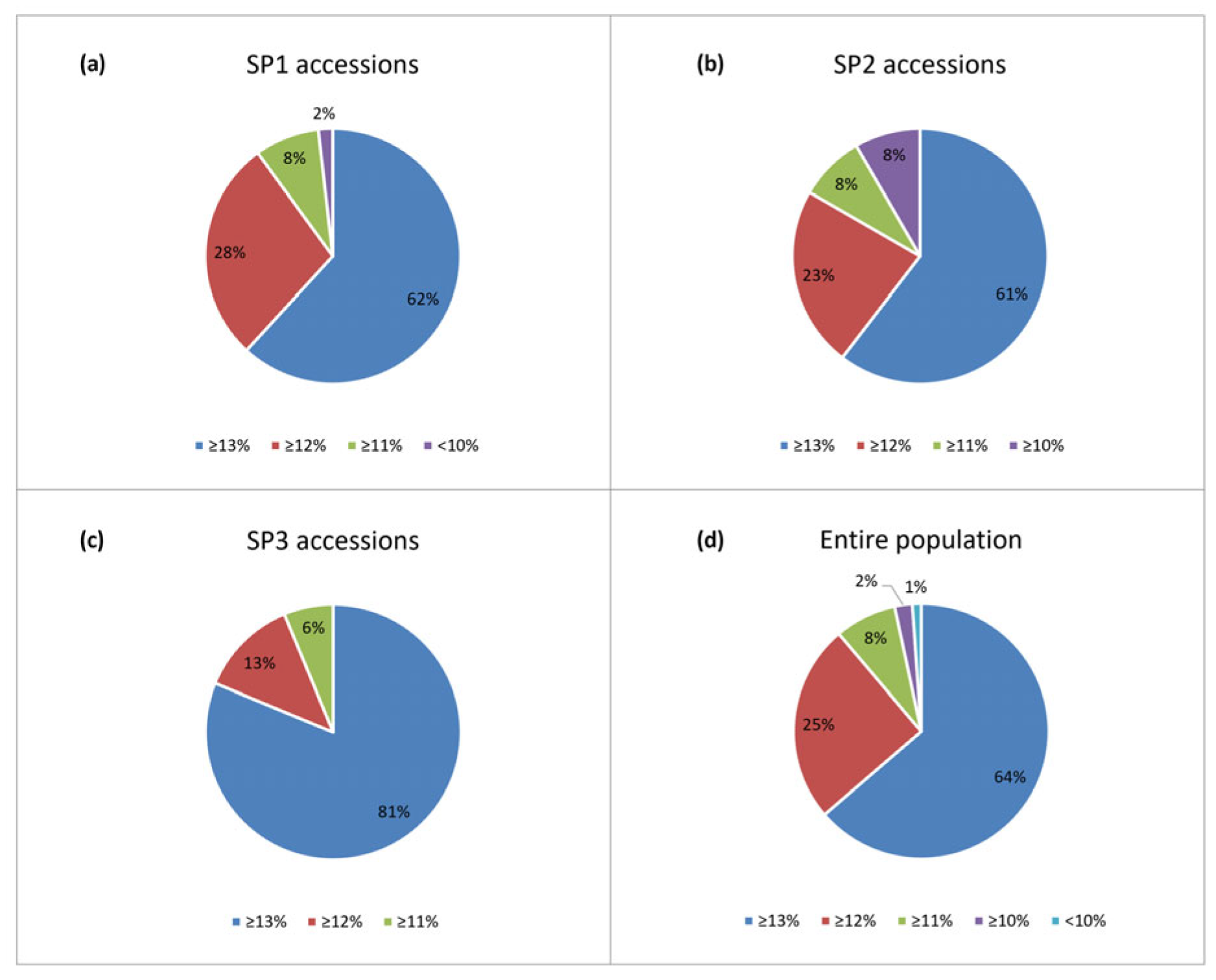

2.1. Phenotypic Variation

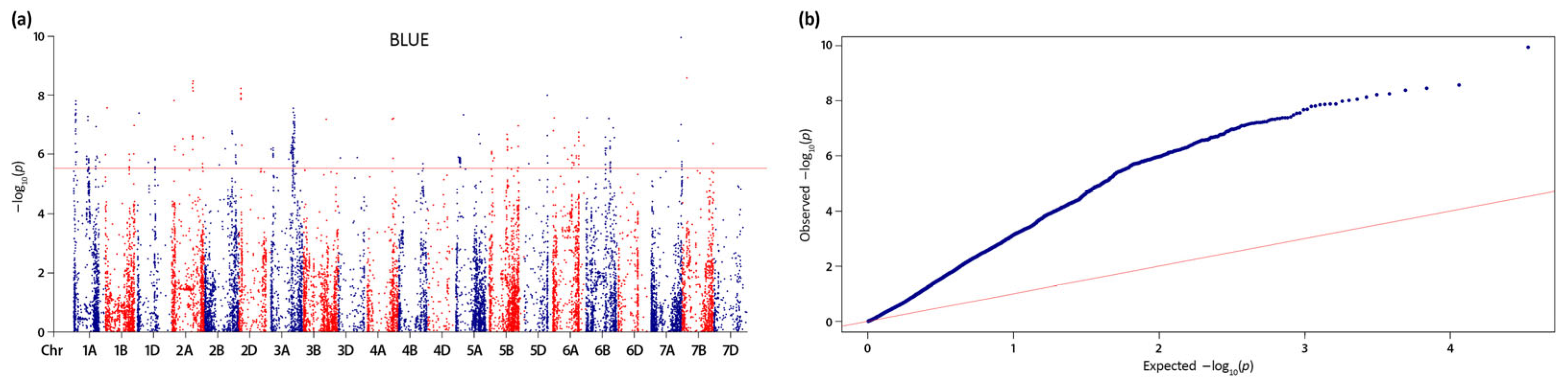

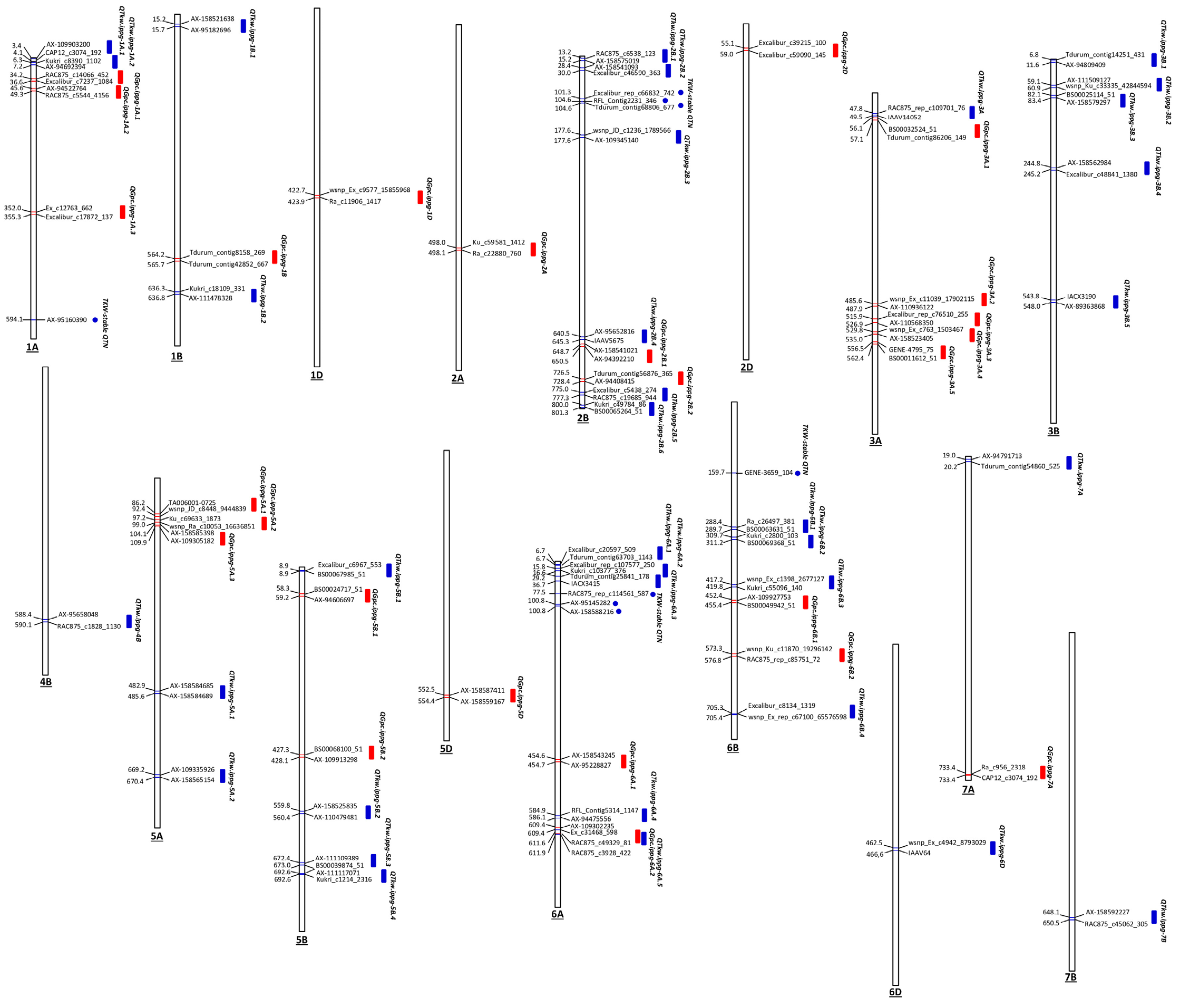

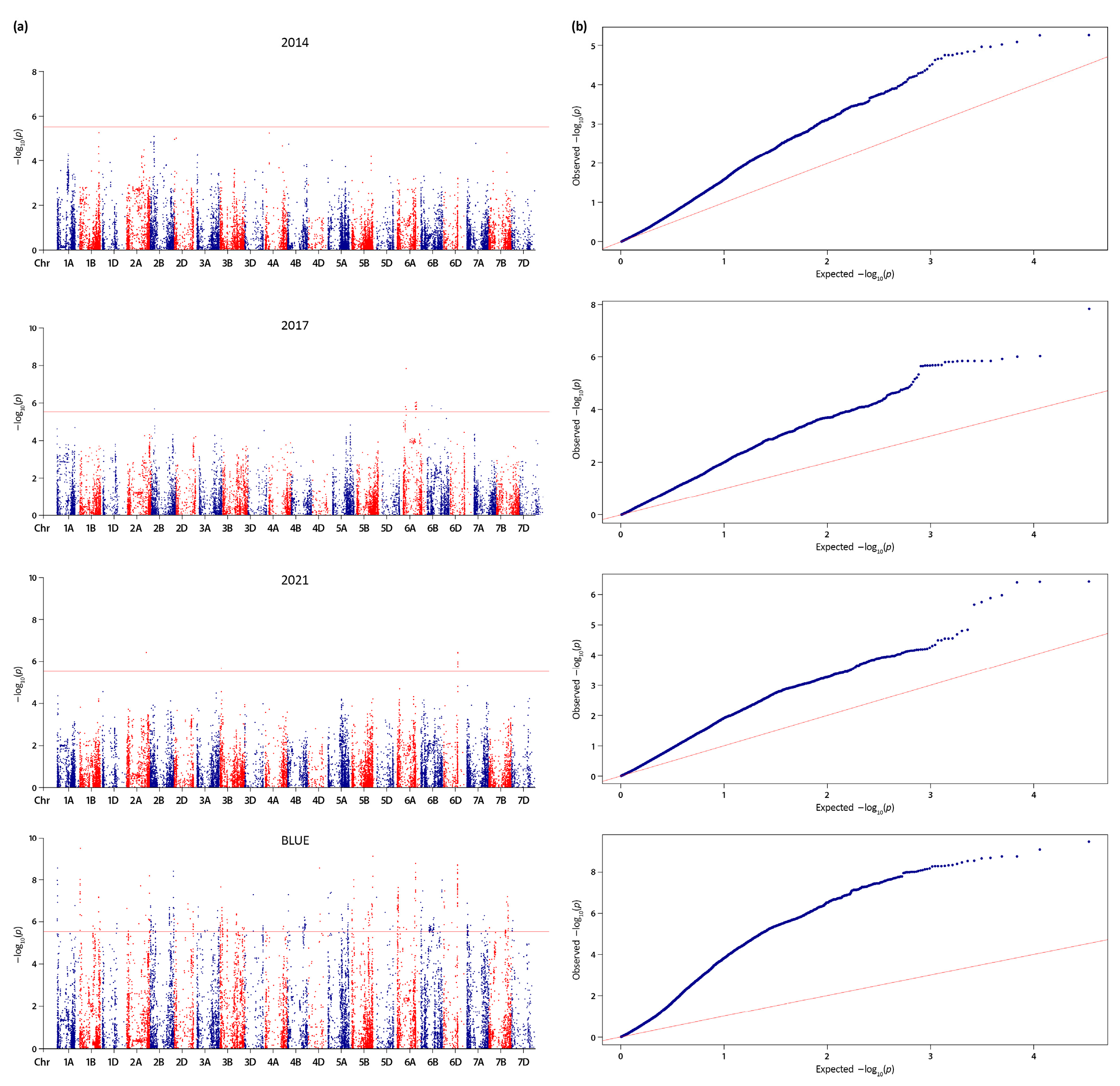

2.2. Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) Estimation, Significant Quantitative Trait Nucleotides (QTNs) and Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL)

2.3. Potential Candidate Genes

3. Discussion

3.1. Phenotypic Variation

3.2. Genomic Regions Associated with Grain Protein Content (GPC) and Thousand Kernel Weight (TKW)

3.3. Putative Candidate Genes Related to Grain Protein Content (GPC) and Thousand Kernel Weight (TKW)

3.3.1. Genes Related to Senescence-Associated Proteolysis, Nutrient Remobilization and Allocation from Source to Sink

3.3.2. Genes Coding for Storage Proteins

3.3.3. Genes Related to Sugar Transport and Starch Metabolism

3.3.4. Regulatory Genes

3.3.5. Genes Related to Early Seed Germination

3.3.6. Genes Related to the Regulation of Grain Size and Weight

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Phenotyping

4.3. Statistical Analyses

4.4. Association Mapping and Candidate Gene Search

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Veraverbeke, W.S.; Delcour, J.A. Wheat protein composition and properties of wheat glutenin in relation to breadmaking functionality. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 42, 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, R.J. Wheat for bread and other foods. In Bread Wheat. Improvement and Production. FAO Plant Production and Protection Series No. 30; Curtis, B.S.; Rajaram, S.; Gómez Macpherson, H., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2002. (https://www.fao.org/3/y4011e/y4011e0w.htm#bm32).

- Barneix, A.J. Physiology and biochemistry of source-regulated protein accumulation in the wheat grain. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 164, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewry, P.R.; Hassall, K.L.; Grausgruber, H.; Andersson, A.A.M.; Lampi, A.-M.; Piironen, V.; Rakszegi, M.; Ward, J.L.; Lovegrove, A. Do modern types of wheat have lower quality for human health? Nutrition Bulletin 2020, 45, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.; Woodruff, D.R.; Philips, I.G.; Basford, K.E.; Gilmour, A.R. Genotype-by-management interactions for grain yield and grain protein concentration of wheat. Field Crop. Res. 2001, 70, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oury, F.X.; Godin, C. Yield and grain protein concentration in bread wheat: how to use the negative relationship between the two characters to identify favourable genotypes? Euphytica 2007, 157, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidig, F.; Piepho, H.P.; Rentel, D.; Drobek, T.; Meyer, U.; Huesken, A. Breeding progress, environmental variation and correlation of winter wheat yield and quality traits in german official variety trials and on-farm during 1983–2014. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, M.; Mohler, V.; Hartl, L. Genetics of the inverse relationship between grain yield and grain protein content in common wheat. Plants 2022, 11, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, R.; Bhinderwala, F.; Morton, M.; Powers, R.; Rose, D.J. Metabolic profiling of historical and modern wheat cultivars using proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdrakov, P. For wheat from Pavlikeni. Seed Prod. 1945, 4, 132–141. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Ganeva, G.; Korzun, V.; Landjeva, S.; Tsenov, N.; Atanasova, M. Identification, distribution and effects on agronomic traits of the semi-dwarfing Rht alleles in Bulgarian bread wheat cultivars. Euphytica 2005, 145, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, A.; Landjeva, S.; Nagel, M.; Rehman Arif, M.A.; Allam, M.; Agacka, M.; Doroszewska, T.; Lohwasser, U. Plant genetic resources for food and agriculture (PGRFA) – maintenance and research. Genet. Plant Physiol. 2014, 4, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.; Eckermann, P.; Haefele, S.; Satija, S.; Sznajder, B.; Timmins, A.; Baumann, U.; Wolters, P.; Mather, D.E.; Fleury, D. Genome-wide association mapping of grain yield in a diverse collection of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) evaluated in southern Australia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paina, C.; Gregersen, P.L. Recent advances in the genetics underlying wheat grain protein content and grain protein deviation in hexaploid wheat. Plant Biol. 2023, 25, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, N.; Hennequet, C.; Berard, P. Dry matter and nitrogen accumulation in wheat kernel: genetic variation in rate and duration of grain filling. J. Genet. Breed. 2001, 55, 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Alqudah, A.M.; Sallam, A.; Baenziger, P.S.; Börner, A. GWAS: Fast-forwarding gene identification and characterization in temperate cereals: Lessons from barley—A review. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 22, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daba, S.D.; Tyagi, P.; Brown-Guedira, G.; Mohammadi, M. Genome-wide association studies to identify loci and candidate genes controlling kernel weight and length in a historical United States wheat population. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, A.; Hu, W.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Xie, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. Appraising the genetic architecture of kernel traits in hexaploid wheat using GWAS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muqaddasi, Q.H.; Brassac, J.; Ebmeyer, E.; Kollers, S.; Korzun, V.; Argillier, O.; Stiewe, G.; Plieske, J.; Ganal, M.W.; Röder, M.S. Prospects of GWAS and predictive breeding for European winter wheat’s grain protein content, grain starch content, and grain hardness. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemu, A.; El Baouchi, A.; El Hanafi, S.; Kehel, Z.; Eddakhir, K.; Tadesse, W. Genetic analysis of grain protein content and dough quality traits in elite spring bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) lines through association study. J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 100, 103214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufo, R.; López, A.; Lopes, M.S.; Bellvert, J.; Soriano, J.M. Identification of quantitative trait loci hotspots affecting agronomic traits and high-throughput vegetation indices in rainfed wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 735192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, S.; Alemu, A.; Abdelmula, A.A.; Badawi, G.H.; Al-Abdallat, A.; Tadesse, W. Genome-wide association analysis uncovers stable QTLs for yield and quality traits of spring bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) across contrasting environments. Plant Gene 2021, 25C, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonova, I.N.; Kiseleva, A.A.; Berezhnaya, A.A.; Stasyuk, A.I.; Likhenko, I.E.; Salina, E.A. Identification of QTLs for grain protein content in Russian spring wheat varieties. Plants 2022, 11, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Sharma, R.; Balding, D.; Cockram, J.; Mackay, I.J. Genome-wide association mapping of Hagberg falling number, protein content, test weight, and grain yield in U.K. wheat. Crop Sci. 2022, 62, 965–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomari, D.Z.; Schierenbeck, M.; Alqudah, A.M.; Alqahtani, M.D.; Wagner, S.; Rolletschek, H.; Borisjuk, L.; Röder, M.S. Wheat grains as a sustainable source of protein for health. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, G.; Guo, X.; Chi, S.; Yu, H.; Jin, K.; Huang, H.; Wang, D.; Wu, C.; Tian, J.; Chen, J.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Deng, Z. Genetic dissection of protein and starch during wheat grain development using QTL mapping and GWAS. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1189887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kartseva, T.; Alqudah, A.M.; Aleksandrov, V.; Alomari, D.Z.; Doneva, D.; Arif, M.A.R.; Börner, A.; Misheva, S. Nutritional genomic approach for improving grain protein content in wheat. Foods 2023, 12, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnappa, G.; Khan, H.; Krishna, H.; Devate, N.B.; Kumar, S.; Mishra, C.N.; Parkash, O.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, M.; Mamrutha, H.M.; Singh, G.P.; Singh, G. Genome-wide association study for grain protein, thousand kernel weight, and normalized difference vegetation index in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Genes 2023, 14, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Arif, M.A.R.; Shamshad, M.; Rawale, K.S.; Brar, A.; Burgueño, J.; Shokat, S.; Ravinder Kaur, R.; Vikram, P.; Srivastava, P.; Sandhu, N.; Singh, J.; Kaur, S.; Chhuneja, P.; Singh, S. Preliminary dissection of grain yield and related traits at differential nitrogen levels in diverse pre-breeding wheat germplasm through association mapping. Mol. Biotechnol. 2023, 65, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrka, M.; Krajewski, P.; Bednarek, P.T.; Rączka, K.; Drzazga, T.; Matysik, P.; Martofel, R.; Woźna-Pawlak, U.; Jasińska, D.; Niewińska, M.; Ługowska, B.; Ratajczak, D.; Sikora, T.; Witkowski, E.; Dorczyk, A.; Tyrka, D. Genome-wide association mapping in elite winter wheat breeding for yield improvement. J. Appl. Genet. 2023, 64, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannam, V.R.R.; Lopes, M.; Guzman, C.; Soriano, J.M. Uncovering the genetic basis for quality traits in the Mediterranean old wheat germplasm and phenotypic and genomic prediction assessment by cross-validation test. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 4, 1127357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrov, V.; Kartseva, T.; Alqudah, A.M.; Kocheva, K.; Tasheva, K.; Börner, A.; Misheva, S. Genetic diversity, linkage disequilibrium and population structure of Bulgarian bread wheat assessed by genome-wide distributed SNP markers: from old germplasm to semi-dwarf cultivars. Plants 2021, 10, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.M.; Pettersson, M.E.; Carlborg, O. A century after Fisher: Time for a new paradigm in quantitative genetics. Trends Genet. 2013, 29, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, M.A.R.; Waheed, M.Q.; Lohwasser, U.; Shokat, S.; Alquddah, A.M.; Volkmar, C.; Börner, A. Genetic insight into the insect resistance in bread wheat exploiting the untapped natural diversity. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 898905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathan, N.D.; Krishnappa, G.; Singh, A.-M.; Govindan, V. Mapping QTL for phenological and grain-related traits in a mapping population derived from high-zinc-biofortified wheat. Plants 2023, 12, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, B.; Tesfaye, K.; Ortiz, R.; Johansson, E.; Hailesilassie, T.; Hammenhag, C.; Hailu, F.; Geleta, M. Marker-trait association analyses revealed major novel QTLs for grain yield and related traits in durum wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1009244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathan, N.D.; Krishna, H.; Ellur, R.K.; Sehgal, D.; Govindan, V.; Ahlawat, A.K.; Krishnappa, G.; Jaiswal, J.P.; Singh, J.B.; Saiprasad, S.V.; Ambati, D.; Singh, S.M.; Bajpai, K.; Mahendru-Singh, A. Genome-wide association study identifies loci and candidate genes for grain micronutrients and quality traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Wei, D.; Chen, L.; Hu, Y.-G. Multi-locus GWAS of quality traits in bread wheat: mining more candidate genes and possible regulatory Network. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, S.; Arif, M.A.R.; Hameed, A. A GBS-based GWAS analysis of adaptability and yield traits in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Appl. Genet. 2020, 62, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, C.; Dang, P.; Gao, L.; Wang, J.; Tao, J.; Qin, X.; Feng, B.; Gao, J. How does the environment affect wheat yield and protein content response to drought? A meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 896985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Meng, S.; Duan, M.; Ye, N.; Zhang, J. Environmental stimuli: A major challenge during grain filling in cereals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Hou, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W.; Fan, Y.; Huang, Z. Post-flowering soil waterlogging curtails grain yield formation by restricting assimilates supplies to developing grains. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 944308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, M.; Striker, G.G.; Colmer, T.D.; Pedersen, O. Mechanisms of waterlogging tolerance in wheat – a review of root and shoot physiology. Plant, Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1068–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooding, M.J.; Ellis, R.H.; Shewry, P.R.; Schofield, J.D. Effects of restricted water availability and increased temperature on the grain filling, drying and quality of winter wheat. J. Cereal Sci. 2003, 37, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, D.; Mondal, S.; Guzman, C.; Garcia Barrios, G.; Franco, C.; Singh, R.; Dreisigacker, S. Validation of candidate gene-based markers and identification of novel loci for thousand-grain weight in spring bread wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Liu, B.; Fedak, G.; Liu, Z. Genomic constitution and variation in five partial amphiploids of wheat—Thinopyrum intermedium as revealed by GISH, multicolor GISH and seed storage protein analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgieva, M.; Sepsi, A.; Tyankova, N.; Molnár-Láng, M. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of two high protein wheat-Thinopyrum intermedium partial amphiploids. J. Appl. Gen. 2011, 52, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatiukha, A.; Filler, N.; Lupo, I.; Lidzbarsky, G.; Klymiuk, V.; Korol, A.B.; Pozniak, C.; Fahima, T.; Krugman, T. Grain protein content and thousand kernel weight QTLs identified in a durum × wild emmer wheat mapping population tested in five environments. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xiang, L.; Zhong, X.; Gong, F.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Genome-wide association study reveals novel genomic regions associated with high grain protein content in wheat lines derived from wild emmer wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeque, R.C.; van Biljon, A.; Labuschagne, M.T. Defining associations between grain yield and protein quantity and quality in wheat from the three primary production regions of South Africa. J. Cereal Sci. 2018, 79, 294e302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cseh, A.; Poczai, P.; Kiss, T.; Balla, K.; Berki, Z.; Horváth, A.; Kuti, C.; Karsai, I. Exploring the legacy of Central European historical winter wheat landraces. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, M.; Pascual, L.; Faci, I.; Fernández, M.; Ruiz, M.; Benavente, E.; Giraldo, P. Exploring the end-use quality potential of a collection of spanish bread wheat landraces. Plants 2021, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Xu, D.; Hanif, M.; Xia, X.; He, Z. Genetic architecture underpinning yield component traits in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 33, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Mullan, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, A.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yan, G. Major genomic regions responsible for wheat yield and its components as revealed by meta-QTL and genotype–phenotype association analyses. Planta 2020, 252, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, P.; Sheikh, I.; Saini, D.K.; Mir, R.R.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Tyagi, V. Consensus genomic regions associated with grain protein content in hexaploid and tetraploid wheat. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1021180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, H.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Guo, D.; Zhai, S.; Chen, A.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, C.; You, M.; Peng, H.; Liang, R.; Ni, Z.; Sun, Q.; Li, B. Genome-wide association study of six quality-related traits in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under two sowing conditions. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, K.S.; Mihalyov, P.D.; Lewien, M.J.; Pumphrey, M.O.; Carter, A.H. Genomic selection and genome-wide association studies for grain protein content stability in a nested association mapping population of wheat. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, M.; García-Abadillo, J.; Uauy, C.; Ruiz, M.; Giraldo, P.; Pascual, L. Genome wide association in Spanish bread wheat landraces identifies six key genomic regions that constitute potential targets for improving grain yield related traits. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltaher, S.; Sallam, A.; Emara, H.A.; Nower, A.A.; Salem, K.F.M.; Börner, A.; Baenziger, P.S.; Mourad, A.M.I. Genome-wide association mapping revealed SNP alleles associated with spike traits in wheat. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, F.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Z.; Cui, D.; Chen, F. Genome-wide association study for 13 agronomic traits reveals distribution of superior alleles in bread wheat from the Yellow and Huai Valley of China. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017, 15, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, A.M.; Haile, J.K.; Alomari, D.Z.; Pozniak, C.J.; Kobiljski, B.; Börner, A. Genome-wide and SNP network analyses reveal genetic control of spikelet sterility and yield-related traits in wheat. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumari, J.; Bhusal, N.; Pradhan, A.K.; Budhlakoti, N.; Mishra, D.C.; Chauhan, D.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.K.; Reynolds, M.; Singh, G.P.; Singh, K.; Sareen, S. Genome-wide association study reveals genomic regions associated with ten agronomical traits in wheat under late-sown conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 549743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chidzanga, C.; Daniel Mullan, D.; Roy, S.; Baumann, U.; Garcia, M. Nested association mapping-based GWAS for grain yield and related traits in wheat grown under diverse Australian environments. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 4437–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrill, P.; Harrington, S.A.; Simmonds, J.; Uauy, C. Identification of transcription factors regulating senescence in wheat through gene regulatory network modelling. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 1740–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, N.; Islam, S.; Juhasz, A.; Ma, W. Wheat leaf senescence and its regulatory gene network. Crop J. 2021, 9, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Hao, C.; Wang, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, X. Identification and development of a functional marker of TaGW2 associated with grain weight in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2011, 122, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puccio, G.; Ingraffia, R.; Giambalvo, D.; Frenda, A.S.; Harkess, A.; Sunseri, F.; Mercati, F. Exploring the genetic landscape of nitrogen uptake in durum wheat: genome-wide characterization and expression profiling of NPF and NRT2 gene families. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1302337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadaleta, A.; Nigro, D.; Giancaspro, A.; Blanco, A. The glutamine synthetase (GS2) genes in relation to grain protein content of durum wheat. Funct. Integr. Genomics 2011, 11, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Kong, F.; Zhao, Y.; Sishen Li, S. Haplotype, molecular marker and phenotype effects associated with mineral nutrient and grain size traits of TaGS1a in wheat. Field Crops Res. 2013, 154, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Halford, N.G. Cereal seed storage proteins: Structures, properties and role in grain utilization. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Singh, N.K. Wheat triticin: A potential target for nutritional quality improvement. Asian J. Biotech. 2011, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancaspro, A.; Giove, S.L.; Zacheo, S.A.; Blanco, A.; Gadaleta, A. Genetic variation for protein content and yield-related traits in a durum population derived from an inter-specific cross between hexaploid and tetraploid wheat cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schierenbeck, M.; Alqudah, A.M.; Ulrike Lohwasser, U.; Tarawneh, R.A.; Simón, M.R.; Börner, A. Genetic dissection of grain architecture related traits in a winter wheat population. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, E.N.C.; Johnson, P.E.; Alexeev, Y. Food Antigens. In Food Allergy: Expert Consult Basic; James, J.M., Burks, B., Eigenmann, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Edinburgh, London, New York, Oxford, Philadelphia, St Louis, Sydney, Toronto, 2012; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, J.; Liu, H.; Li, T.; Wang, K.; Hao, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. TaBT1, affecting starch synthesis and thousand kernel weight, underwent strong selection during wheat improvement. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 1497–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Han, S.; Chen, L.; Mu, J.; Duan, L.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Li, X. Expression and regulation of genes involved in the reserve starch biosynthesis pathway in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Crop J. 2021, 9, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Kumar, J.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, S. Multi-locus genome-wide association mapping for spike-related traits in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Hao, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase genes, associated with kernel weight, underwent selection during wheat domestication and breeding. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Li, L.; Lv, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. TaGW2-6A allelic variation contributes to grain size possibly by regulating the expression of cytokinins and starch-related genes in wheat. Planta 2017, 246, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibarat, Z.; Saidi, A. Senescence-associated proteins and nitrogen remobilization in grain filling under drought stress condition. J. Genet. Engin. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uauy, C.; Distelfeld, A.; Fahima, T.; Blechl, A.; Dubkovsky, J.A. NAC gene regulating senescence improves grain protein, zinc, and iron content in wheat. Science 2006, 314, 1298–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andleeb, T.; Borrill, P. Wheat NAM genes regulate the majority of early monocarpic senescence transcriptional changes including nitrogen remobilisation genes. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2023, 13, jkac275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; An, K.; Guo, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Chang, S.; Rossi, V.; Jin, F.; Cao, X.; Xin, M.; Peng, H.; Hu, Z.; Guo, W.; Du, J.; Ni, Z.; Sun, Q.; Yao, Y. The endosperm-specific transcription factor TaNAC019 regulates glutenin and starch accumulation and its elite allele improves wheat grain quality. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, U.; Hou, J.; Hao, C.; Zhang, X. TaNAC020 homoeologous genes are associated with higher thousand kernel weight and kernel length in Chinese wheat. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 956921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, L.; Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Gong, H.; Luo, J.; Hou, Q.; Zhou, T.; Lu, T.; Zhu, J.; Shangguan, Y.; Chen, E.; Gong, C.; Zhao, Q.; Jing, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Cui, L.; Fan, D.; Lu, Y.; Weng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Liu, K.; Wei, X.; An, K.; An, G.; Han, B. OsSPL13 controls grain size in cultivated rice. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, K.; Li, A.; Mao, L. SQUAMOSA promoter-binding protein-like transcription factors: star players for plant growth and development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010, 52, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Mendoza, M.; Diaz, I.; Martinez, M. Insights on the proteases involved in barley and wheat grain germination. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.A.R.; Börner, A. An SNP based GWAS analysis of seed longevity in wheat. Cereal Res. Comm. 2020, 48, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whan, A.; Dielen, A.-S.; Mieog, J.; Bowerman, A.F.; Robinson, H.M.; Byrne, K.; Colgrave, M.; Larkin, P.J.; Howitt, C.A.; Morell, M.K.; Ral, J.-P. Engineering α-amylase levels in wheat grain suggests a highly sophisticated level of carbohydrate regulation during development. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 5443–5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Wang, S.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Ren, J.; Wang, X.; Niu, H.; Yin, J. The role of thioredoxin h in protein metabolism during wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed germination. Plant Physiol. Biochem 2013, 67, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, F.O.; Berna, A. Germins and germin-like proteins: plant do-all proteins. But what do they do exactly? Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2001, 39, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.Y.; Yan, J.; He, Z.H.; Wu, L.; Xia, X.C. Characterization of a cell wall invertase gene TaCwi-A1 on common wheat chromosome 2A and development of functional markers. Mol. Breed. 2012, 29, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Pu, A.; Dong, Z.; Wei, X.; Wan, X. Molecular mechanisms controlling grain size and weight and their biotechnological breeding applications in maize and other cereal crops. J. Adv. Res. 2023, S2090-1232(23)00265-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Fan, C.C.; Xing, Y.Z.; Jiang, Y.H.; Luo, L.J.; Sun, L.; Shao, D.; Xu, C.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, O. Natural variation in GS5 plays an important role in regulating grain size and yield in rice. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 1266–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, T.; Hao, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X. TaGS5-3A, a grain size gene selected during wheat improvement for larger kernel and yield. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillett, B.J.; Hale, C.O.; Martin, J.M.; Giroux, M.J. Genes impacting grain weight and number in wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ssp. aestivum). Plants 2022, 11, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossé, J.; Huet, J.C.; Baudet, J. The amino acid composition of wheat grain as a function of nitrogen content. J. Cereal Sci. 1985, 3, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STATISTICA, version 14; StatSoft Inc.: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2020.

- Yu, J.; Buckler, E.S. Genetic association mapping and genome organization of maize. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2006, 17, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Yu, J. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling corrects for population structure in association mapping with different sample types. Genetics 2009, 182, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Shah, T.; Warburton, M.L.; Li, Q.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Chai, Y.; Fu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, S.; Bai, G.; Meng, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, J. Genetic analysis and characterization of a new maize association mapping panel for quantitative trait loci dissection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S. qqman: an R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and manhattan plots. J. Open Source Software 2018, 3, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaux, M.; Rogers, G.; Letellier, T.; Flores, R.; Alfama, F.; Pommier, C.; Mohellibi, N.; Durand, S.; Kimmel, E.; Michotey, C.; et al. Linking the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium bread wheat reference genome sequence to wheat genetic and phenomic data. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trait | Env. | Mean* | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. | CV % | h2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPC (%) | Sofia 2014 | 13.2b | 1.46 | 7.6 | 16.8 | 11.09 | 0.64 |

| Sofia 2017 | 12.9b | 2.06 | 6.0 | 16.8 | 15.90 | 0.78 | |

| Sofia 2021 | 14.2a | 1.62 | 7.1 | 19.4 | 11.43 | 0.69 | |

| Average | 13.4 | 1.34 | 9.4 | 16.8 | 10.00 | 0.82 | |

| BLUE | 13.4 | 0.51 | 11.6 | 14.7 | 3.81 | ||

| TKW (g) | Sofia 2014 | 43.1b | 6.43 | 22.2 | 65.8 | 14.92 | 0.77 |

| Sofia 2017 | 44.0b | 4.72 | 31.0 | 58.2 | 10.73 | 0.64 | |

| Sofia 2021 | 48.6a | 5.42 | 24.4 | 61.6 | 11.14 | 0.70 | |

| Average | 45.2 | 4.28 | 33.7 | 55.0 | 9.46 | 0.81 | |

| BLUE | 45.4 | 2.25 | 39.6 | 51.8 | 4.94 |

| (a) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of Variation | SS | df | MS | F | P-value | F crit |

| Genotype (G) | 962.685 | 178 | 5.408 | 3.010 | 0.0000 | 1.233 |

| Environment (E) | 145.483 | 2 | 72.741 | 40.485 | 0.0000 | 3.021 |

| G × E | 639.638 | 356 | 1.797 | 7.210 | 0.0000 | 3.320 |

| Total | 1747.805 | 536 | ||||

| (b) | ||||||

| Source of Variation | SS | df | MS | F | P-value | F crit |

| Genotype (G) | 9792.257 | 178 | 55.013 | 2.897 | 0.0000 | 1.233 |

| Environment (E) | 3128.650 | 2 | 1564.325 | 82.375 | 0.0000 | 3.021 |

| G × E | 6760.582 | 356 | 18.990 | 4.3643 | 0.0000 | 4.092 |

| Total | 19681.49 | 536 | ||||

| GPC-2017 | GPC-2021 | GPC-BLUE | TKW-2014 | TKW-2017 | TKW-2021 | TKW-BLUE | |

| GPC-2014 | 0.69*** | 0.50*** | 0.93*** | 0.00 | -0.09 | -0.08 | -0.05 |

| GPC-2017 | 0.10 | 0.61*** | 0.04 | 0.01 | -0.01 | -0.02 | |

| GPC-2021 | 0.47*** | 0.16* | -0.01 | 0.12 | 0.06 | ||

| GPC-BLUE | -0.01 | -0.10 | -0.07 | 0.02 | |||

| TKW-2014 | 0.39*** | 0.30*** | 0.60*** | ||||

| TKW-2017 | 0.53*** | 0.42*** | |||||

| TKW-2021 | 0.38*** |

| QTL | Position range (Mbp)a | SNPs | Peak SNP | Peak SNP -log10(p) | Allele | Total QTL effect | R2 range | High confidence genes | Co- located locib |

| QGpc.ippg-1A.1 | 32.17 – 38.57 | 4 | Excalibur_c7237_1084 | 7.36 | A/G | 16.10 | 17-19% | 81 | |

| QGpc.ippg-1A.2 | 43.58 – 51.29 | 15 | AX-94522764 | 7.79 | A/G | 49.26 | 14-20% | 59 | [28,57] |

| QGpc.ippg-1A.3 | 350.01 – 357.34 | 7 | wsnp_JD_c40990_29127031 | 5.85 | A/G | -18.06 | 13-14% | 55 | [37] |

| QGpc.ippg-1B | 562.66 – 567.17 | 3 | Tdurum_contig8158_269 | 6.00 | A/G | 17.22 | 13-15% | 37 | |

| QGpc.ippg-1D | 420.18 – 426.36 | 5 | wsnp_Ex_c9577_15855968 | 5.84 | T/C | -5.74 | 13-14% | 74 | |

| QGpc.ippg-2A | 496.54 – 499.61 | 5 | Ra_c22880_760 | 8.38 | A/G | 22.58 | 16-22% | 16 | |

| QGpc.ippg-2B.1 | 646.95 – 652.19 | 5 | Kukri_c4294_371 | 6.78 | A/G | -18.69 | 17% | 44 | [19] |

| QGpc.ippg-2B.2 | 724.85 – 730.10 | 3 | Tdurum_contig56876_365 | 5.96 | T/C | -5.81 | 14% | 10 | |

| QGpc.ippg-2D | 52.54 – 61.61 | 7 | D_contig28346_467 | 8.22 | T/C | -40.52 | 20-22% | 111 | |

| QGpc.ippg-3A.1 | 54.14 – 59.01 | 10 | BS00032524_51 | 6.21 | T/C | 25.95 | 14-15% | 88 | |

| QGpc.ippg-3A.2 | 483.60 – 489.86 | 6 | wsnp_Ex_c11039_17902115 | 6.31 | A/G | -13.00 | 15% | 46 | [56] |

| QGpc.ippg-3A.3 | 513.89 – 521.21 | 15 | BobWhite_c9468_453 | 6.58 | A/G | -7.27 | 14-16% | 62 | [27] |

| QGpc.ippg-3A.4 | 519.31 – 537.00 | 27 | AX-158523405 | 7.55 | T/C | -4.95 | 13-19% | 120 | |

| QGpc.ippg-3A.5 | 554.46 – 564.35 | 16 | BS00011612_51 | 7.33 | A/G | 12.44 | 15-18% | 69 | |

| QGpc.ippg-5A.1 | 84.17 – 94.44 | 10 | Tdurum_contig81753_70 | 5.87 | A/G | 12.05 | 14% | 46 | |

| QGpc.ippg-5A.2 | 95.23 – 101.02 | 3 | wsnp_Ex_rep_c110023_92574403 | 5.89 | T/C | 17.72 | 14% | 25 | |

| QGpc.ippg-5A.3 | 102.15 – 111.94 | 13 | wsnp_Ku_c328_679106 | 5.86 | A/G | 6.45 | 14% | 47 | |

| QGpc.ippg-5B.1 | 56.83 – 60.66 | 5 | BS00024717_51 | 6.08 | T/C | -5.90 | 15% | 29 | |

| QGpc.ippg-5B.2 | 425.77 – 429.63 | 5 | BS00068100_51 | 6.25 | A/G | -6.40 | 15% | 35 | [57] |

| QGpc.ippg-5D | 550.49 – 556.35 | 4 | Kukri_c15823_196 | 7.99 | T/C | -0.91 | 14-23% | 107 | [28] |

| QGpc.ippg-6A.1 | 453.14 – 456.16 | 3 | Tdurum_contig78006_158 | 5.96 | A/G | 5.28 | 13-14% | 32 | |

| QGpc.ippg-6A.2 | 607.88 – 613.01 | 8 | wsnp_Ex_c1153_2213588 | 6.74 | T/C | -12.62 | 14-17% | 136 | |

| QGpc.ippg-6B.1 | 450.41 – 457.45 | 4 | AX-158552532 | 6.57 | A/G | -12.03 | 14-16% | 33 | |

| QGpc.ippg-6B.2 | 571.32 – 578.81 | 8 | wsnp_Ku_c11870_19296142 | 6.45 | T/C | 23.87 | 13-16% | 57 | |

| QGpc.ippg-7A | 732.36 – 734.37 | 3 | AX-158589978 | 5.75 | T/C | 5.63 | 13-14% | 41 | |

| In total: | 1,460 | ||||||||

| (a) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QTL | Position range (Mbp)a | SNPs | Peak SNP | Peak SNP -log10 (p) |

Allele | Total QTL effect | R2 range | High confidence genes | Co- located locib |

| QTkw.ippg-1A.1 | 1.38 - 6.06 | 3 | CAP12_c3074_192 | 7.96 | A/G | 1.31 | 14-19% | 70 | |

| QTkw.ippg-1A.2 | 4.32 – 9.19 | 4 | AX-94692394 | 8.54 | T/C | 3.11 | 11-21% | 91 | [53] |

| QTkw.ippg-1B.1 | 13.74 – 17.25 | 11 | BS00108057_51 | 8.01 | T/C | -1.76 | 14-22% | 74 | |

| QTkw.ippg-1B.2 | 634.73 – 638.30 | 4 | BS00039135_51 | 7.17 | A/C | -3.55 | 9-17% | 47 | [21] |

| QTkw.ippg-2B.1 | 11.47 – 16.91 | 4 | BobWhite_c26803_89 | 6.75 | T/C | 0.17 | 14-16% | 99 | [53] |

| QTkw.ippg-2B.2 | 26.67 – 31.69 | 9 | Excalibur_c46590_363 | 6.29 | T/C | -2.00 | 13-15% | 104 | |

| QTkw.ippg-2B.3 | 175.95 – 180.40 | 3 | wsnp_Ex_c51461_55394646 | 5.88 | A/G | -4.70 | 12-13% | 23 | |

| QTkw.ippg-2B.4 | 638.79 – 647.01 | 16 | AX-95652816 | 6.67 | A/G | -5.76 | 13-16% | 73 | |

| QTkw.ippg-2B.5 | 773.26 – 779.03 | 7 | Excalibur_c5438_274 | 8.40 | T/C | 2.39 | 15-21% | 76 | |

| QTkw.ippg-2B.6 | 798.33 – 802.95 | 4 | BS00065264_51 | 6.62 | T/G | -3.38 | 13-16% | 45 | |

| QTkw.ippg-3A | 45.83 – 51.48 | 3 | BS00011111_51 | 6.70 | T/G | -1.57 | 14-16% | 61 | [53] |

| QTkw.ippg-3B.1 | 4. 54 -13.40 | 6 | AX-94783816 | 5.93 | A/T | 0.71 | 13-16% | 186 | [59] |

| QTkw.ippg-3B.2 | 58.06 – 62.67 | 5 | RAC875_c34484_67 | 6.67 | A/G | -4.47 | 13-16% | 49 | [36] |

| QTkw.ippg-3B.3 | 80.27 – 85.23 | 4 | wsnp_Ex_c1097_2105209 | 6.03 | A/G | 2.88 | 13-14% | 41 | |

| QTkw.ippg-3B.4 | 242.98– 246.79 | 4 | CAP8_rep_c4453_136 | 5.94 | T/C | 0.04 | 13-14% | 28 | [58] |

| QTkw.ippg-3B.5 | 542.04 – 549.85 | 4 | BS00062734_51 | 6.38 | A/G | -0.10 | 13-15% | 69 | |

| QTkw.ippg-4B | 586.73 – 592.55 | 6 | Ex_c25467_851 | 6.07 | T/C | 0.01 | 13-14% | 39 | [63] |

| QTkw.ippg-5A.1 | 480.95 – 487.60 | 4 | AX-158584685 | 6.18 | A/G | -0.09 | 13-14% | 69 | [30] |

| QTkw.ippg-5A.2 | 667.20 – 672.45 | 6 | AX-109335926 | 6.83 | T/G | 3.89 | 13-16% | 57 | [58,63] |

| QTkw.ippg-5B.1 | 7.41 – 10.45 | 4 | BS00067985_51 | 6.12 | T/C | -3.91 | 14% | 45 | |

| QTkw.ippg-5B.2 | 558.27 – 561.94 | 5 | AX-110484654 | 6.45 | A/G | 4.57 | 14-15% | 28 | |

| QTkw.ippg-5B.3 | 670.94 – 674.45 | 3 | CAP12_c2231_114 | 6.84 | A/C | 5.33 | 8-16% | 42 | [63] |

| QTkw.ippg-5B.4 | 691.13 – 694.14 | 3 | Kukri_c1214_2316 | 6.75 | T/C | -5.44 | 14-16% | 37 | [53,63] |

| QTkw.ippg-6A.1 | 5.23 – 8.23 | 4 | Tdurum_contig63703_1143 | 6.75 | T/C | 6.49 | 15-16% | 56 | [60] |

| QTkw.ippg-6A.2 | 14.27 – 18.07 | 4 | RAC875_c2253_2011 | 5.99 | T/C | 0.61 | 11-14% | 91 | [59] |

| QTkw.ippg-6A.3 | 27.71 – 38.19 | 38 | BS00023140_51 | 7.62 | T/C | -16.71 | 14-18% | 165 | |

| QTkw.ippg-6A.4 | 583.44 – 587.60 | 5 | AX-94475556 | 7.11 | T/C | 4.28 | 13-17% | 51 | [53,58] |

| QTkw.ippg-6A.5 | 607.93 – 613.36 | 11 | Kukri_c11902_580 | 8.76 | T/C | 1.50 | 17-22% | 163 | [53,61,63] |

| QTkw.ippg-6B.1 | 286.42 – 291.69 | 4 | Kukri_c26279_503 | 5.71 | T/C | -0.04 | 13% | 23 | |

| QTkw.ippg-6B.2 | 307.75 – 313.20 | 4 | RAC875_c41604_1001 | 5.75 | T/C | -0.11 | 13% | 10 | |

| QTkw.ippg-6B.3 | 415.23 – 421.77 | 3 | Kukri_c55096_140 | 5.69 | A/C | -1.54 | 13% | 19 | |

| QTkw.ippg-6B.4 | 703.28 – 707.38 | 3 | wsnp_Ex_rep_c67100_65576598 | 7.50 | A/G | -1.69 | 17-18% | 112 | [53] |

| QTkw.ippg-6D | 459.54 – 469.55 | 40 | AX-158600736 | 8.70 | T/C | 26.55 | 16-22% | 211 | |

| QTkw.ippg-7A | 18.01 – 21.17 | 9 | AX-94791713 | 5.80 | T/C | 10.51 | 13% | 70 | [53] |

| QTkw.ippg-7B | 646.65 – 652.04 | 8 | AX-158592437 | 6.75 | A/G | 0.15 | 13% | 53 | [62] |

| In total: | 2,477 | ||||||||

| (b) | |||||||||

| QTL/Chr. | Position (Mbp) | Env. | SNP | -log10 (p) | Allele | Effect | R2 | High confidence genes |

Co- located locib |

| Stable QTNs within a LD blockc | |||||||||

| QTkw.ippg-1A.2 | 6.32 | 2017, BLUE | Kukri_c8390_1102 | 6.92 | A/G | -5.01 | 11% | ||

| QTkw.ippg-1B.2 | 636.75 | 2021, BLUE | BS00039135_51 | 7.17 | A/C | -2.00 | 17% | [21] | |

| QTkw.ippg-1B.2 | 636.75 | 2021, BLUE | BobWhite_c2844_569 | 7.15 | A/C | -2.00 | 17% | [21] | |

| QTkw.ippg-1B.2 | 636.80 | 2021, BLUE | AX-111478328 | 7.14 | A/G | -1.99 | 17% | [21] | |

| QTkw.ippg-6A.2 | 16.57 | 2017, BLUE | RAC875_c2253_2011 | 5.99 | T/C | -1.49 | 14% | ||

| QTkw.ippg-6A.2 | 16.57 | 2017, BLUE | Kukri_c10377_376 | 5.74 | A/G | -1.45 | 13% | ||

| Stable QTNs not in a LD block | |||||||||

| 1A | 594.10 | 2017, BLUE | AX-95160390 | 6.77 | C/G | 1.56 | 17% | 21 | |

| 2B | 101.30 | 2017, BLUE | Excalibur_rep_c66832_742 | 5.68 | T/G | 4.10 | 13% | 27 | [53] |

| 2B | 104.57 | 2017, BLUE | RFL_Contig2231_346* | 5.57 | A/G | 1.94 | 13% | 38 | [53] |

| 2B | 104.58 | 2017, BLUE | Tdurum_contig68806_677* | 5.74 | T/C | -1.95 | 13% | [53] | |

| 6A | 77.53 | 2017, 2021, BLUE | RAC875_rep_c114561_587 | 5.81 | A/G | 4.24 | 14% | 29 | [58] |

| 6A | 100.77 | 2017, BLUE | AX-95145282** | 7.84 | A/G | 4.78 | 20% | 49 | |

| 6A | 100.80 | 2017, BLUE | AX-158588216** | 5.65 | A/G | 4.09 | 13% | ||

| 6B | 159.70 | 2017, BLUE | GENE-3659_104 | 5.84 | T/C | -4.24 | 14% | 51 | |

| In total: | 215 | ||||||||

| QTL | Gene ID | Anotation function |

|---|---|---|

| QGpc.ippg-1A.1 | TraesCS1A01G052600 | Germin-like protein |

| TraesCS1A01G052700 | Germin-like protein | |

| TraesCS1A01G052900 | Germin-like protein | |

| TraesCS1A01G053000 | Germin-like protein | |

| TraesCS1A01G053100 | Germin-like protein | |

| TraesCS1A01G053700 | Ubiquitin activating enzyme E1 | |

| QGpc.ippg-1A.2 | TraesCS1A01G063600 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 |

| TraesCS1A01G066100 | 11S globulin seed storage protein | |

| TraesCS1A01G069000 | bZIP transcription factor family protein | |

| QGpc.ippg-1A.3 | TraesCS1A01G196300 | 26S proteasome regulatory subunit family protein |

| TraesCS1A01G197400 | WRKY family transcription factor | |

| TraesCS1A01G197600 | Peptide transporter | |

| TraesCS1A01G197700 | Peptide transporter | |

| QGpc.ippg-1B | TraesCS1B01G338500 | Cysteine protease family protein |

| TraesCS1B01G338800 | Thioredoxin | |

| TraesCS1B01G339000 | Thioredoxin | |

| QGpc.ippg-1D | TraesCS1D01G330800 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase MARCH6 |

| TraesCS1D01G331800 | Bifunctional inhibitor/lipid-transfer protein/seed storage 2S albumin superfamily | |

| TraesCS1D01G331900 | Bifunctional inhibitor/lipid-transfer protein/seed storage 2S albumin superfamily | |

| TraesCS1D01G332200 | Basic-leucine zipper (BZIP) transcription factor family | |

| TraesCS1D01G332500 | Thioredoxin | |

| TraesCS1D01G333100 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| QGpc.ippg-2A | TraesCS2A01G289800 | Alpha-amylase |

| TraesCS2A01G289800 | Alpha-amylase | |

| QGpc.ippg-2B.1 | TraesCS2B01G453000 | Ubiquitin-specific protease family C19-related protein |

| TraesCS2B01G453100 | Ubiquitin-specific protease family C19 protein | |

| TraesCS2B01G454300 | WRKY transcription factor | |

| QGpc.ippg-2B.2 | TraesCS2B01G533300 | Sucrose transporter |

| QGpc.ippg-2D | TraesCS2D01G100500 | Thioredoxin, putative |

| TraesCS2D01G100600 | NAC domain protein | |

| TraesCS2D01G100900 | NAC domain protein, | |

| TraesCS2D01G100700 | NAC domain protein, | |

| TraesCS2D01G100800 | NAC domain protein, | |

| TraesCS2D01G101300 | NAC domain protein | |

| TraesCS2D01G101400 | NAC domain protein | |

| TraesCS2D01G102300 | Cysteine protease | |

| TraesCS2D01G104400 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase SHPRH | |

| TraesCS2D01G104500 | WRKY transcription factor | |

| TraesCS2D01G104600 | WRKY transcription factor | |

| TraesCS2D01G104700 | WRKY transcription factor | |

| TraesCS2D01G105400 | Basic-leucine zipper domain | |

| TraesCS2D01G106200 | Cysteine proteinase | |

| TraesCS2D01G109300 | Germin-like protein 1 | |

| QGpc.ippg-3A.1 | TraesCS3A01G085500 | bZIP transcription factor, putative (DUF1664) |

| TraesCS3A01G090700 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase SINA-like 10 | |

| QGpc.ippg-3A.3 | TraesCS3A01G285600 | Proteasome subunit alpha type |

| TraesCS3A01G287800 | Eukaryotic aspartyl protease family protein | |

| TraesCS3A01G289000 | Senescence-associated family protein (DUF581) | |

| TraesCS3A01G289700 | WRKY transcription factor | |

| TraesCS3A01G289800 | PROTEIN TARGETING TO STARCH (PTST) | |

| QGpc.ippg-3A.4 | TraesCS3A01G293700 | BZIP transcription factor family protein, putative |

| TraesCS3A01G297600 | Subtilisin-like protease | |

| TraesCS3A01G299400 | NAM-like protein | |

| QGpc.ippg-3A.5 | TraesCS3A01G318700 | 26S proteasome regulatory subunit S2 1B |

| TraesCS3A01G319300 | Cysteine protease | |

| TraesCS3A01G319800 | Eukaryotic aspartyl protease family protein | |

| QGpc.ippg-5A.1 | TraesCS5A01G073000 | Amino acid transporter, putative |

| TraesCS5A01G076000 | Cysteine protease | |

| QGpc.ippg-5A.3 | TraesCS5A01G081500 | Amino acid transporter family protein, putative |

| QGpc.ippg-5B.1 | TraesCS5B01G054200 | NAC domain-containing protein |

| TraesCS5B01G054600 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS5B01G054700 | Serine-protease HtrA-like | |

| QGpc.ippg-5B.2 | TraesCS5B01G245300 | Peptide transporter |

| QGpc.ippg-5D | TraesCS5D01G543600 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit |

| QGpc.ippg-6A.1 | TraesCS6A01G242000 | WRKY transcription factor |

| TraesCS6A01G243100 | bZIP transcription factor (DUF630 and DUF632) | |

| QGpc.ippg-6A.2 | TraesCS6A01G394200 | Thioredoxin |

| TraesCS6A01G402200 | Mitochondrial metalloendopeptidase OMA1 | |

| TraesCS6A01G402300 | Mitochondrial metalloendopeptidase OMA1 | |

| TraesCS6A01G406700 | NAC domain protein | |

| QGpc.ippg-6B.1 | TraesCS6B01G253400 | Oligopeptide transporter, putative |

| QGpc.ippg-6B.2 | TraesCS6B01G325700 | Senescence-associated family protein, putative (DUF581) |

| TraesCS6B01G325800 | Senescence-associated family protein, putative (DUF581) | |

| TraesCS6B01G327400 | Mitochondrial metalloendopeptidase OMA1 | |

| TraesCS6B01G327500 | Glutamine synthetase | |

| TraesCS6B01G329200 | NAC domain-containing protein | |

| TraesCS6B01G329400 | NAC domain-containing protein 29 | |

| QGpc.ippg-7A | TraesCS7A01G561400 | Cysteine protease, putative |

| TraesCS7A01G562100 | Thioredoxin | |

| TraesCS7A01G563600 | Thioredoxin |

| QTL/stable QTN | Gene ID | Annotation function |

|---|---|---|

| QTkw.ippg-1A.1 | TraesCS1A01G005700 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase ORTHRUS 2 |

| TraesCS1A01G007200 | Gamma-gliadin | |

| TraesCS1A01G007300 | Gamma-gliadin | |

| TraesCS1A01G007400 | Gamma-gliadin | |

| TraesCS1A01G007700 | Gamma-gliadin | |

| TraesCS1A01G008000 | Low molecular weight glutenin subunit | |

| QTkw.ippg-1A.2 | TraesCS1A01G010900 | Low molecular weight glutenin subunit |

| QTkw.ippg-1B.1 | TraesCS1B01G029300 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase pellino homolog 3 |

| QTkw.ippg-1B.2 | TraesCS1B01G407700 | Protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein family |

| TraesCS1B01G407800 | Protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein family | |

| TraesCS1B01G407900 | Protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein family | |

| TraesCS1B01G408000 | Protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein family | |

| QTkw.ippg-2B.1 | TraesCS2B01G025900 | Subtilisin-like protease 6 |

| QTkw.ippg-2B.2 | TraesCS2B01G057600 | NRT1/PTR family protein 2.2 |

| TraesCS2B01G057700 | NRT1/PTR family protein 2.2 | |

| TraesCS2B01G058400 | Serine carboxypeptidase family protein, expressed | |

| TraesCS2B01G062700 | Sucrose transporter-like protein | |

| TraesCS2B01G055700 | Bidirectional sugar transporter SWEET | |

| TraesCS2B01G055800 | Bidirectional sugar transporter SWEET | |

| TraesCS2B01G055900 | Bidirectional sugar transporter SWEET | |

| TraesCS2B01G056000 | Bidirectional sugar transporter SWEET | |

| TraesCS2B01G056100 | Bidirectional sugar transporter SWEET | |

| QTkw.ippg-2B.6 | TraesCS2B01G626000 | Protein NRT1/ PTR FAMILY 5.5 |

| TraesCS2B01G626100 | Protein NRT1/ PTR FAMILY 5.5 | |

| TraesCS2B01G626600 | Protein NRT1/ PTR FAMILY 5.5 | |

| TraesCS2B01G626700 | Protein NRT1/ PTR FAMILY 5.5 | |

| TraesCS2B01G627000 | NAC domain-containing protein, putative | |

| TraesCS2B01G627100 | NAC domain-containing protein, putative | |

| TraesCS2B01G627200 | NAC domain-containing protein, putative | |

| TraesCS2B01G629700 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase SINA-like 10 | |

| QTkw.ippg-3A | TraesCS3A01G077900 | NAC domain-containing protein |

| TraesCS3A01G078400 | NAC domain protein | |

| TraesCS3A01G078500 | E3 ubiquitin ligase family protein | |

| QTkw.ippg-3B.1 | TraesCS3B01G018000 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| TraesCS3B01G018100 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS3B01G018200 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS3B01G019600 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS3B01G026900 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS3B01G027000 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS3B01G027400 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS3B01G027500 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS3B01G028000 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS3B01G028800 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS3B01G028900 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS3B01G014300 | Expansin protein | |

| TraesCS3B01G014400 | Expansin protein | |

| TraesCS3B01G028100 | Cell wall invertase | |

| TraesCS3B01G028500 | Cell wall invertase | |

| QTkw.ippg-3B.2 | TraesCS3B01G092800 | NAC domain-containing protein |

| TraesCS3B01G092900 | NAC domain-containing protein | |

| TraesCS3B01G093300 | NAC domain protein | |

| TraesCS3B01G093400 | E3 ubiquitin ligase family protein | |

| QTkw.ippg-3B.3 | TraesCS3B01G116800 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| TraesCS3B01G116200 | Serine carboxypeptidase, putative | |

| TraesCS3B01G116300 | Serine carboxypeptidase, putative | |

| TraesCS3B01G116400 | Serine carboxypeptidase, putative | |

| QTkw.ippg-3B.4 | TraesCS3B01G208300 | NAC domain-containing protein |

| TraesCS3B01G209300 | Sucrose synthase 3 | |

| QTkw.ippg-3B.5 | TraesCS3B01G336200 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| TraesCS3B01G336900 | ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase small subunit 2 | |

| TraesCS3B01G339100 | Subtilisin-like protease | |

| QTkw.ippg-5A.1 | TraesCS5A01G271500 | NAC domain protein |

| TraesCS5A01G275900 | NAC domain-containing protein | |

| QTkw.ippg-5A.2 | TraesCS5A01G507500 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase SINA-like 10 |

| QTkw.ippg-5B.1 | TraesCS5B01G007600 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| QTkw.ippg-5B.2 | TraesCS5B01G382100 | E3 ubiquitin protein ligase DRIP2 |

| QTkw.ippg-6A.2 | TraesCS6A01G030700 | High affinity nitrate transporter |

| TraesCS6A01G030800 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G030900 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G031000 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G031100 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G031200 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G032400 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G032500 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G032800 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G032900 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G033000 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G033100 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G033200 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| TraesCS6A01G028800 | Subtilisin-like protease | |

| TraesCS6A01G036800 | Subtilisin-like protease | |

| TraesCS6A01G032700 | Expansin protein | |

| QTkw.ippg-6A.3 | TraesCS6A01G057400 | NAC domain-containing protein, putative |

| TraesCS6A01G065600 | NAC domain | |

| TraesCS6A01G065700 | NAC domain | |

| QTkw.ippg-6A.5 | TraesCS6A01G406700 | NAC domain protein |

| QTkw.ippg-6B.1 | TraesCS6B01G214700 | Cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase |

| QTkw.ippg-6B.3 | TraesCS6B01G238700 | High affinity nitrate transporter |

| TraesCS6B01G238800 | High affinity nitrate transporter | |

| QTkw.ippg-6D | TraesCS6D01G390200 | NAC domain protein |

| TraesCS6D01G396300 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| TraesCS6D01G393600 | Sucrose transporter | |

| QTkw.ippg-7A | TraesCS7A01G040900 | Sucrose synthase |

| Stable QTN not in a LD block | ||

| Excalibur_rep_c66832_742 | TraesCS2B01G136000 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| RFL_Contig2231_346* | TraesCS2B01G136200 | Subtilisin-like protease |

| Tdurum_contig68806_677* | TraesCS2B01G137200 | Subtilisin-like protease |

| RAC875_rep_c114561_587 | TraesCS6A01G108300 | NAC domain-containing protein, putative |

| TraesCS6A01G110100 | Squamosa promoter-binding-like protein | |

| AX-95145282**AX-158588216** | TraesCS6A01G125900 | Squamosa promoter-binding protein-like transcription factor |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).