Submitted:

19 February 2024

Posted:

19 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

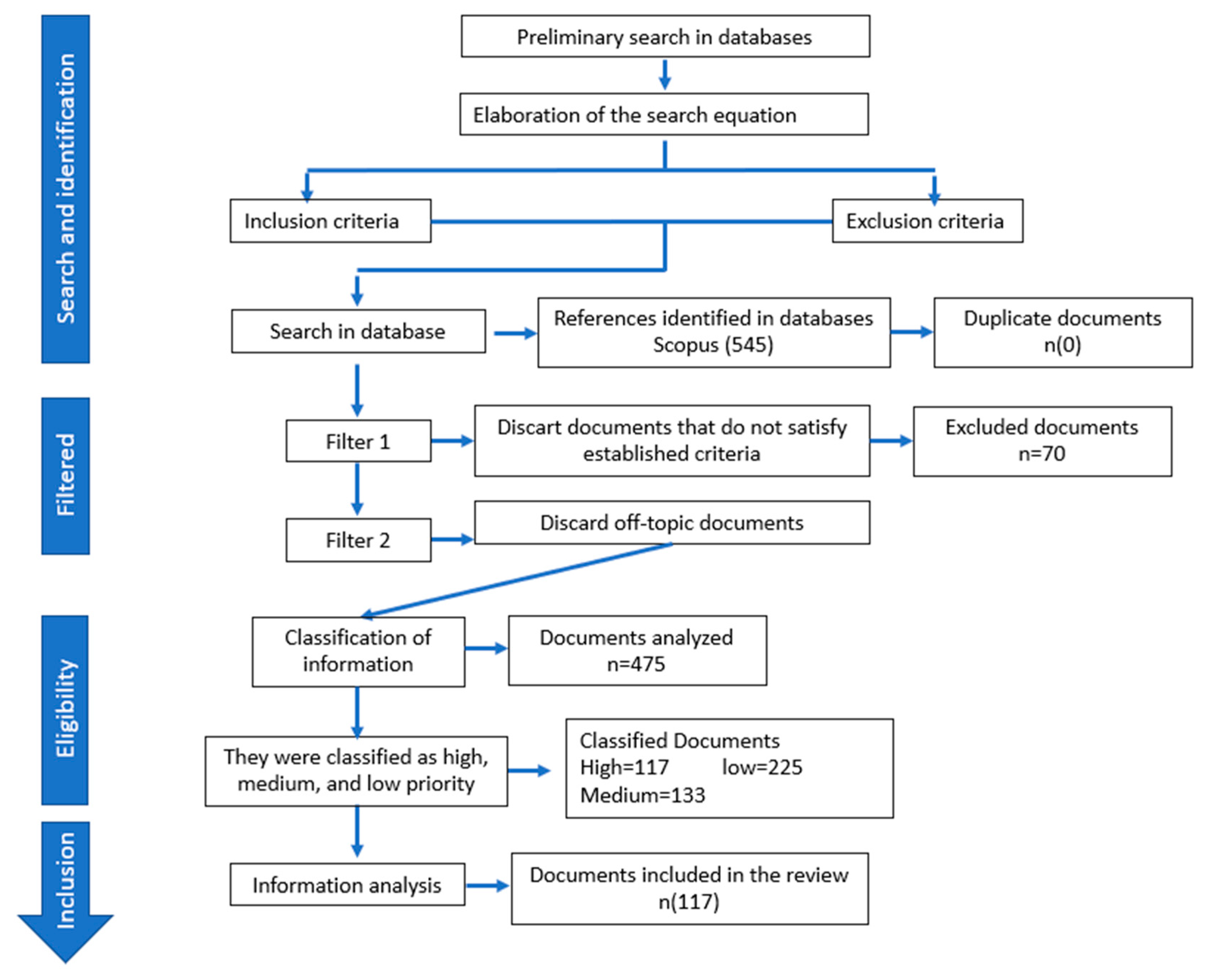

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

1.1. Microbiological characteristics and virulence factors of Acinetobacter baumannii

| Virulence factor | Activity in pathogenesis | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Outer membrane proteins: (OmpA, Omp 33-36, Omp 22) | Adherence and invasion, apoptosis induction, biofilm formation, persistence, and serum resistance. | (17,18) |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Serum resistance, survival during tissue infection, evasion of immune system response. | (18,19) |

| Micronutrient Acquisition System (iron, manganese and zinc) | Competition, and survival, cause the death of host cells | (20) |

| Capsular polysaccharide | Serum resistance, survival during tissue infection, evasion of antimicrobial action | (18,19) |

| Phospholipases (PLC y PLD) | Serum resistance, cytolytic activity, invasion, in vivo survival. | (18) |

| Secretion system type II, V and VI | Adherence and colonization, in vivo survival, bacterial competition, biofilm formation. | (18,19,21) |

| Biofilm | Adherence, survival in environments and resistance to antibiotics | (18,21,22) |

| Quórum sensing | Biofilm formation. | (17) |

| Pili type IV | Motility, adherence, biofilm formation | (13,17) |

| Outer membrane vesicles | Release of virulence factors, horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes. | (17,21) |

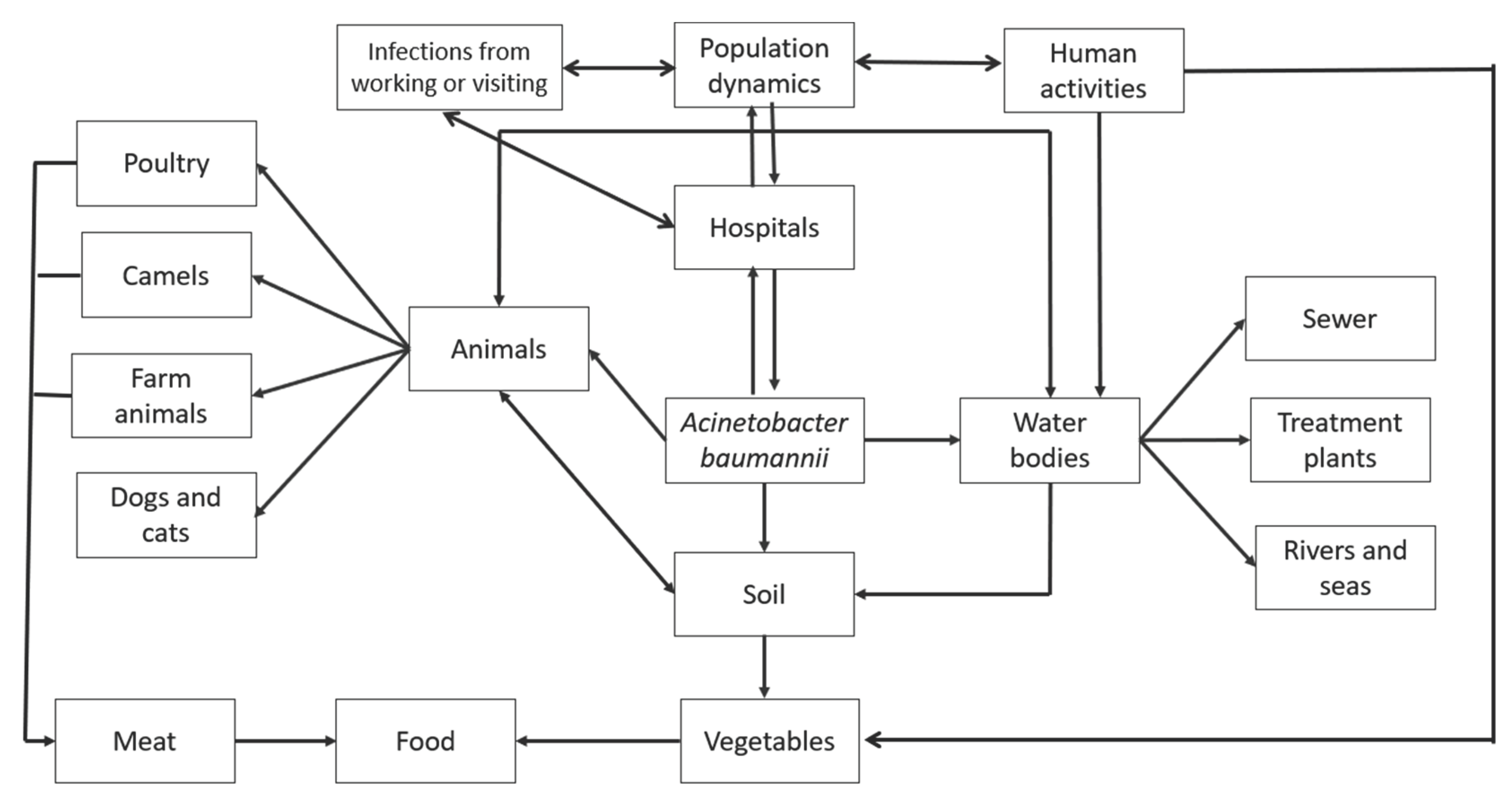

3.2. Natural reservoirs of Acinetobacter baumannii

3.3. Hospital habitats of Acinetobacter baumannii

3.4. Out-of-hospital habitats for Acinetobacter baumannii

3.4.1. Water bodies

3.4.2. Soil, vegetables, and food

3.4.3. Products of animal origin for human consumption

| Animals for consumption | Isolations | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Sheep | Meat | (36,44,46) |

| Goat | Meat | (44,46) |

| Cow | Meat | (44,46,55) |

| Camels | Meat | (36,37,44,46) |

| Pork | Meat, manure | (29,44,56) |

| Chicken/ turkey |

Meat | (36,37,40) |

| Cats | Wounds, Pus, urine, skin | (44,57) |

| Dogs | Wounds, Pus, urine, skin | (44,57) |

| Turkey | Meat | (37,44) |

| Horse | Wounds, pus, catheter | (37,44) |

3.4.4. Domestic animals

3.4.5. Other sites

3.5. Antimicrobial resistance of A. baumannii from out-of-hospital isolates

| Antibiotic group | Gen | Isolates | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ß -lactamases class A |

|

Adjej.- environmental and hospital Anane.- Slaughterhouses, water (from a dam) Shamsizadeh.- Air, water and nearby places hospitals |

(26,63–65) |

| ß -lactamases class B |

|

Adjej.- environmental and hospital Anane.- Slaughterhouses, water (from a dam) |

(26,35,63) |

| Quinolone | abaQ | Clinical samples | (66) |

| Sulfonamide |

sul1 sul2 |

Clinical samples | (67) |

| Tetracyclines |

Tet (A) Tet (B) |

Clinical samples |

(67,68) |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Medina MJ, Legido-Quigley H, Hsu LY. Antimicrobial Resistance in One Health. In: Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications. Springer; 2020. p. 209–29.

- WHO. Resistencia a los antibióticos [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/resistencia-a-los-antibi%C3%B3ticos.

- Abdulhussein TM, Abed AS, Al-Mousawi HM, Abdallah JM, Sattar RJ. Molecular genotyping survey for Bla Tem virulence gene of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates, Iraq. Plant Arch [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Sep 17];20(2):413–5. Available from: http://www.plantarchives.org/SPL%20ISSUE%2020-2/69__413-415_.pdf.

- Hayajneh WA, Al-Azzam S, Yusef D, Lattyak WJ, Lattyak EA, Gould I, et al. Identification of thresholds in relationships between specific antibiotic use and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAb) incidence rates in hospitalized patients in Jordan. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2021 Feb 1;76(2):524–30. [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. https://www.who.int/es/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed#:~:text=Entre%20tales%20bacterias%20se%20incluyen,la%20corriente%20sangu%C3%ADnea%20y%20neumon%C3%ADas. 2017. La OMS publica la lista de las bacterias para las que se necesitan urgentemente nuevos antibióticos.

- Al-Hassan LL, Al- Madboly LA. Molecular characterisation of an Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak. Infection Prevention in Practice. 2020 Jun 1;2(2). [CrossRef]

- Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007 Dec;5(12):939–51. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi S, Raoufi Z, Fakoor MH. Physicochemical and structural characterization, epitope mapping and vaccine potential investigation of a new protein containing Tetratrico Peptide Repeats of Acinetobacter baumannii: An in-silico and in-vivo approach. Mol Immunol. 2021 Dec 1;140:22–34. [CrossRef]

- Baran Aİ, Çelik M, Arslan Y, Demirkıran H, Sünnetçioğlu M, Sünnetçioğlu A. Evaluation of risk factors in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by acinetobacter baumannii. Bali Medical Journal. 2020;9(1):253–8. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien N, Barboza-Palomino M, Ventura-León J, Caycho-Rodríguez T, Sandoval-Díaz JS, López-López W, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). A bibliometric analysis. Revista Chilena de Anestesia. 2020;49(3):408–15. [CrossRef]

- Sahu RR, Parabhoi L. Bibliometric Study of Library and Information Science Journal Articles during 2014 2018. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology. 2020 Dec 3;40(06):390–5. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elnasser R, Hussein M, Rahim A, Mahmoud MA, Elkhawaga AA, Hassnein KM. Bulletin of Pharmaceutical Sciences ـــ Antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii: An urgent need for new therapy and infection control [Internet]. Vol. 43, Bull. Pharm. Sci., Assiut University. 2020. Available from: http://bpsa.journals.ekb.eg/.

- Gedefie A, Demsis W, Ashagrie M, Kassa Y, Tesfaye M, Tilahun M, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii biofilm formation and its role in disease pathogenesis: A review. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:3711–9. [CrossRef]

- Smith MG, Gianoulis TA, Pukatzki S, Mekalanos JJ, Ornston LN, Gerstein M, et al. New insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis revealed by high-density pyrosequencing and transposon mutagenesis. Genes Dev [Internet]. 2007 Mar 1 [cited 2023 Dec 21];21(5):601–14. Available from: https://genesdev.cshlp.org/content/21/5/601.abstract.

- Pongparit S, Bunchaleamchai A, Watthanakul N, Boonma N, Massarotti K, Khamuan S, et al. Prevalence of blaoxa genes in carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii isolates from clinical specimens from nopparatrajathanee hospital. J Curr Sci Technol. 2021 Sep 1;11(3):367–74.

- Vanegas-Múnera JM, Roncancio-Villamil G, Jiménez-Quiceno JN. Acinetobacter baumannii: importancia clínica, mecanismos de resistencia y diagnóstico. Revista CES MEDICINA [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2022 Sep 24];28(2):233–46. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/cesm/v28n2/v28n2a08.pdf.

- Moubareck CA, Halat DH. Insights into Acinetobacter baumannii: A review of microbiological, virulence, and resistance traits in a threatening nosocomial pathogen. Vol. 9, Antibiotics. MDPI AG; 2020.

- Ridha DJ, Ali MR, Jassim KA. Occurrence of Metallo-β-lactamase Genes among Acinetobacter baumannii Isolated from Different Clinical samples. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2019;13(2):1111–9. [CrossRef]

- Harding CM, Hennon SW, Feldman MF. Uncovering the mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. Vol. 16, Nature Reviews Microbiology. Nature Publishing Group; 2018. p. 91–102. [CrossRef]

- Lee CR, Lee JH, Park M, Park KS, Bae IK, Kim YB, et al. Biology of Acinetobacter baumannii: Pathogenesis, antibiotic resistance mechanisms, and prospective treatment options. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017 Mar 13;7(MAR). [CrossRef]

- Morris FC, Dexter C, Kostoulias X, Uddin MI, Peleg AY. The Mechanisms of Disease Caused by Acinetobacter baumannii. Front Microbiol. 2019;10(JULY). [CrossRef]

- Saipriya K, Swathi CH, Ratnakar KS, Sritharan V. Quorum-sensing system in Acinetobacter baumannii: a potential target for new drug development. J Appl Microbiol [Internet]. 2020 Jan 26 [cited 2023 Dec 21];128(1):15–27. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jambio/article-abstract/128/1/15/6714869?login=false.

- Doughari HJ, Ndakidemi PA, Human IS, Benade S. The ecology, biology and pathogenesis of acinetobacter spp.: An overview. Microbes Environ. 2011;26(2):101–12. [CrossRef]

- Jung J, Park W. Acinetobacter species as model microorganisms in environmental microbiology: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol [Internet]. 2015 Mar 19 [cited 2023 Dec 20];99(6):2533–48. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00253-015-6439-y. 1007.

- Almasaudi SB. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: Epidemiology and resistance features. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2018 Mar;25(3):586–96. [CrossRef]

- Anane A Y, Apalata T, Vasaikar S, Okuthe GE, Songca S. Prevalence and molecular analysis of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in the extra-hospital environment in Mthatha, South Africa. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2019 Nov 1;23(6):371–80. [CrossRef]

- Carvalheira A, Casquete R, Silva J, Teixeira P. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Acinetobacter spp. isolated from meat. Int J Food Microbiol [Internet]. 2017 Feb [cited 2023 Dec 20];243:58–63. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168160516306493?casa_token=iyeoArAWEw0AAAAA:ZfsGwGNQe2At94J9iZPRYKdc_tkjlcA3RQRgwcXktcpC5fklSQ6Pxsw88EWZJj8rz4I_oU6ZhQ4.

- Ramirez MS, Bonomo RA, Tolmasky ME. Carbapenemases: Transforming Acinetobacter baumannii into a Yet More Dangerous Menace. Biomolecules [Internet]. 2020 May 6 [cited 2023 Dec 20];10(5):720. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2218-273X/10/5/720.

- Hrenovic J, Durn G, Goic-Barisic I, Kovacic A. Occurrence of an Environmental Acinetobacter baumannii Strain Similar to a Clinical Isolate in Paleosol from Croatia. Appl Environ Microbiol [Internet]. 2014 May [cited 2023 Dec 20];80(9):2860–6. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/full/10.1128/aem.00312-14?casa_token=8b5-m53MQm8AAAAA%3AUcicBEM_DrfvXg6710xYlakIt1_Z3DrRrAeuCmgIkj7DF26TiVkjOSqcIhziFAJT22vVw1_nuUtL9Ws.

- Galarde-López M, Velazquez-Meza ME, Bobadilla-del-Valle M, Cornejo-Juárez P, Carrillo-Quiroz BA, Ponce-de-León A, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Clonal Distribution of E. coli, Enterobacter spp. and Acinetobacter spp. Strains Isolated from Two Hospital Wastewater Plants. Antibiotics [Internet]. 2022 Apr 29 [cited 2023 Dec 20];11(5):601. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/11/5/601.

- Jovcic B, Novovic K, Dekic S, Hrenovic J. Colistin Resistance in Environmental Isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Microbial Drug Resistance [Internet]. 2021 Mar 1 [cited 2023 Dec 20];27(3):328–36. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32762604/.

- Furlan JPR, Pitondo-Silva A, Stehling EG. New STs in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii harbouring β-lactamases encoding genes isolated from Brazilian soils. J Appl Microbiol [Internet]. 2018 Aug 31 [cited 2023 Dec 20];125(2):506–12. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jambio/article-abstract/125/2/506/6714378?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false.

- Suresh S, Aditya V, Deekshit VK, Manipura R, Premanath R. A rare occurrence of multidrug-resistant environmental Acinetobacter baumannii strains from the soil of Mangaluru, India. Arch Microbiol [Internet]. 2022 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Dec 20];204(7). Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00203-022-03035-0.

- Bitar I, Medvecky M, Gelbicova T, Jakubu V, Hrabak J, Zemlickova H, et al. Complete Nucleotide Sequences of mcr-4.3 -Carrying Plasmids in Acinetobacter baumannii Sequence Type 345 of Human and Food Origin from the Czech Republic, the First Case in Europe. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet]. 2019 Oct [cited 2023 Dec 20];63(10). Available from: chrome-https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6761559/pdf/AAC.01166-19.pdf.

- Cho GS, Li B, Rostalsky A, Fiedler G, Rösch N, Igbinosa E, et al. Diversity and antibiotic susceptibility of Acinetobacter strains from milk powder produced in Germany. Front Microbiol. 2018 Mar 27;9(MAR). [CrossRef]

- Elbehiry A, Marzouk E, Moussa IM, Dawoud TM, Mubarak AS, Al-Sarar D, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii as a community foodborne pathogen: Peptide mass fingerprinting analysis, genotypic of biofilm formation and phenotypic pattern of antimicrobial resistance. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021 Jan 1;28(1):1158–66. [CrossRef]

- Tavakol M, Momtaz H, Mohajeri P, Shokoohizadeh L, Tajbakhsh E. Genotyping and distribution of putative virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genes of Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from raw meat. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018 Oct 4;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Berlau J, Aucken HM, Houang E, Pitt TL. Isolation of Acinetobacter spp including A. baumannii from vegetables: implications for hospital-acquired infections. Journal of Hospital Infection [Internet]. 1999 Jul [cited 2023 Dec 20];42(3):201–4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10439992/.

- Malta RCR, Ramos GL de PA, Nascimento J dos S. From food to hospital: we need to talk about Acinetobacter spp. Germs [Internet]. 2020 Sep [cited 2023 Dec 20];10(3):210–7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7572206/.

- Ghaffoori Kanaan MH, Al-Shadeedi SMJ, Al-Massody AJ, Ghasemian A. Drug resistance and virulence traits of Acinetobacter baumannii from Turkey and chicken raw meat. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Jun [cited 2023 Dec 20];70:101451. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0147957120300400?via%3Dihub.

- Francey T, Gaschen F, Nicolet J, Burnens AP. The Role of Acinetobacter baumannii as a Nosocomial Pathogen for Dogs and Cats in an Intensive Care Unit. J Vet Intern Med [Internet]. 2000 Mar 28 [cited 2023 Dec 20];14(2):177–83. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2000.tb02233.x.

- Kimura Y, Harada K, Shimizu T, Sato T, Kajino A, Usui M, et al. Species distribution, virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance of Acinetobacter spp. isolates from dogs and cats: a preliminary study. Microbiol Immunol [Internet]. 2018 Jul 16 [cited 2023 Dec 20];62(7):462–6. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1348-0421.12601.

- Lysitsas M, Triantafillou E, Chatzipanagiotidou I, Antoniou K, Valiakos G. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles of Acinetobacter baumannii Strains, Isolated from Clinical Cases of Companion Animals in Greece. Vet Sci [Internet]. 2023 Oct 29 [cited 2023 Dec 20];10(11):635. Available from: Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles of Acinetobacter baumannii Strains, Isolated from Clinical Cases of Companion Animals in Greece.

- Nocera FP, Attili AR, De Martino L. Acinetobacter baumannii: Its clinical significance in human and veterinary medicine. Vol. 10, Pathogens. MDPI AG; 2021. p. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Wareth G, Abdel-Glil MY, Schmoock G, Steinacker U, Kaspar H, Neubauer H, et al. Draft Genome Sequence of an Acinetobacter baumannii Isolate Recovered from a Horse with Conjunctivitis in Germany. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2019 Nov 27;8(48). [CrossRef]

- Askari N, Momtaz H, Tajbakhsh E. Acinetobacter baumannii in sheep, goat, and camel raw meat: Virulence and antibiotic resistance pattern. AIMS Microbiol. 2019;5(3):272–84. [CrossRef]

- Deng Y, Du H, Tang M, Wang Q, Huang Q, He Y, et al. Biosafety assessment of Acinetobacter strains isolated from the Three Gorges Reservoir region in nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2021 Oct 5 [cited 2023 Dec 20];11(1):19721. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-99274-0#citeas.

- Ly TDA, Amanzougaghene N, Hoang VT, Dao TL, Louni M, Mediannikov O, et al. Molecular Evidence of Bacteria in Clothes Lice Collected from Homeless People Living in Shelters in Marseille. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases [Internet]. 2020 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Dec 20];20(11):872–4. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/vbz.2019.2603.

- Martinez J, Liu C, Rodman N, Fernandez JS, Barberis C, Sieira R, et al. Human fluids alter DNA-acquisition in Acinetobacter baumannii. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis [Internet]. 2019 Mar [cited 2023 Dec 21];93(3):183–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30420211/.

- Milligan EG, Calarco J, Davis BC, Keenum IM, Liguori K, Pruden A, et al. A Systematic Review of Culture-Based Methods for Monitoring Antibiotic-Resistant Acinetobacter, Aeromonas, and Pseudomonas as Environmentally Relevant Pathogens in Wastewater and Surface Water. Curr Environ Health Rep [Internet]. 2023 Feb 23 [cited 2023 Dec 21];10(2):154–71. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40572-023-00393-9#citeas.

- Kovacic A, Music MS, Dekic S, Tonkic M, Novak A, Rubic Z, et al. Transmission and survival of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outside hospital setting. International Microbiology. 2017;20(4):165–9. [CrossRef]

- Stenström TA, Okoh AI, University of Uyo AA. Antibiogram of environmental isolates of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus from Nkonkobe Municipality, South Africa. Fresenius Environ Bull [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2023 Dec 20];25(8):93–7. Available from: https://openscholar.dut.ac.za/handle/10321/2545.

- Kanafani Z, Kanj S. UpToDate. 2015 [cited 2023 Dec 20]. Acinetobacter infection: Treatment and prevention. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acinetobacter-infection-treatment-and-prevention.

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ. Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. Vol. 42, FEMS Microbiology Reviews. Oxford University Press; 2018. p. 68–80.

- Klotz P, Higgins PG, Schaubmar AR, Failing K, Leidner U, Seifert H, et al. Seasonal occurrence and carbapenem susceptibility of bovine Acinetobacter baumannii in Germany. Front Microbiol. 2019;10(FEB). [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Estrada V, Vali L, Hamouda A, Evans BA, Castillo-Ramírez S. Acinetobacter baumannii Sampled from Cattle and Pigs Represent Novel Clones. Microbiol Spectr. 2022 Aug 31;10(4). [CrossRef]

- van der Kolk JH, Endimiani A, Graubner C, Gerber V, Perreten V. Acinetobacter in veterinary medicine, with an emphasis on Acinetobacter baumannii. Vol. 16, Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. Elsevier Ltd; 2019. p. 59–71. [CrossRef]

- Gentilini F, Turba ME, Pasquali F, Mion D, Romagnoli N, Zambon E, et al. Hospitalized Pets as a Source of Carbapenem-Resistance. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2018 Dec 6 [cited 2023 Dec 20];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02872/full.

- Mitchell KE, Turton JF, Lloyd DH. Isolation and identification of Acinetobacter spp. from healthy canine skin. Vet Dermatol [Internet]. 2018 Jun 11 [cited 2023 Dec 21];29(3):240. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/vde.12528.

- Unger F, Eisenberg T, Prenger-Berninghoff E, Leidner U, Semmler T, Ewers C. Imported Pet Reptiles and Their “Blind Passengers”—In-Depth Characterization of 80 Acinetobacter Species Isolates. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2022 May 1 [cited 2024 Feb 10];10(5). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/10/5/893.

- Townsend J, Park AN, Gander R, Orr K, Arocha D, Zhang S, et al. Acinetobacter Infections and Outcomes at an Academic Medical Center: A Disease of Long-Term Care. Open Forum Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Dec 21];2(1). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article/2/1/ofv023/2337943.

- Ababneh Q, Abu Laila S, Jaradat Z. Prevalence, genetic diversity, antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from urban environments. J Appl Microbiol [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Feb 10];133(6):3617–33. Available from: https://ami-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jam.15795.

- Adjei AY, Vasaikar SD, Apalata T, Okuthe EG, Songca SP. Phylogenetic analysis of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from different sources using Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2021 Dec;96:105132. [CrossRef]

- Genteluci GL, Gomes DBC, Pereira D, Neves M de C, de Souza MJ, Rangel K, et al. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: differential adherence to HEp-2 and A-549 cells. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2020 Jun 1;51(2):657–64. [CrossRef]

- Shamsizadeh Z, Nikaeen M, Esfahani BN, Mirhoseini SH, Hatamzadeh M, Hassanzadeh A. Detection of antibiotic resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in various hospital environments: Potential sources for transmission of acinetobacter infections. Environ Health Prev Med. 2017;22(1). [CrossRef]

- Attia NM, Elbaradei A. Fluoroquinolone resistance conferred by gyrA, parC mutations, and AbaQ efflux pump among Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates causing ventilator-associated pneumonia. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2020 Dec 1;67(4):234–8. [CrossRef]

- Chan AP, Choi Y, Clarke TH, Brinkac LM, White RC, Jacobs MR, et al. AbGRI4, a novel antibiotic resistance island in multiply antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2020 Oct 1;75(10):2760–8. [CrossRef]

- Ghajavand H, Esfahani BN, Havaei A, Fazeli H, Jafari R, Moghim S. Isolation of bacteriophages against multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Vol. 12, Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2017. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).