Introduction

The term “autopsy” has a Greek origin and is derived from the combination of two words such as “Auto” (αὐτό), meaning “self” or “from oneself,” and “Opsis” (ὄψις), meaning “vision” or “observation”; so literally “to observe from oneself” or “to see from oneself”.

Autopsy is divided into two types: the “hospital autopsy” is the examination of the corpse carried out by the Pathologist to ascertain the cause of death and to check or verify the diagnosis made in life on behalf of the Health Authority, and the “forensic autopsy” is the examination of the corpse carried out by the forensic Pathologist to ascertain the time, cause, means, and manner of death for the purposes of justice when a crime is presumed, on behalf of the Magistrate.

The first law authorising human dissection dates back to 1231, attributed to Federico II, emperor of the Sacred Roman Empire. During the Renaissance, human dissections became popular in the universities of northern Italy. In the 16th century, Andreas Vesalius from Brussels ushered in the modern era of the study of anatomy, advancing the anatomical concept of disease following the recognition of abnormal findings during anatomical dissections. In June 1543, Vesalius published the “De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body)” [

1]. Giovanni Morgagni was among the first to correlate clinical symptoms with organic changes, introducing the anatomical-clinical concept in medicine [

2]. His autopsy reports, published in 1761, “De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis (The Seats and Causes of Diseases Investigated by Anatomy)”, numbered more than 700 cases and included descriptions of coronary arteriosclerosis, aneurysms, endocarditis, pneumonia, cirrhosis of the liver, fatty liver, kidney stones, hydronephrosis related to urethral stricture and various types of cancer.

Karl von Rokitansky performed more than 30,000 autopsies, and with his “Handbook of Pathological Anatomy”, autopsy became an important and integral part of medicine during the first half of the 19th century [

3]; and introduced the autopsy study of organs in situ.

At the same time, Rudolph Ludwig Carl Virchow also applied microscopic examination to diseased tissues and became known as the founder of modern pathology [

4].

In 1876, Virchow published a book on autopsy techniques in which he introduced a detailed post-mortem technique to identify organ abnormalities. Specifically, after examining organs in situ, Virchow proceeded to extract individual organs and perform further dissection (“one by one”); in opposition to the technique developed earlier by Rokitansky. Maurice Letulle described the autopsy technique on mass removal (“en masse”) [

5]; the thoracic, cervical, abdominal, and pelvic organs were removed as a single organ block and then dissected into organ blocks. In 1901, Albrecht Ghon described the autopsy technique on bulk removal (“en bloc”); Thoracic and cervical organs, abdominal organs, and the urogenital system are removed as organ blocks.

There is a slow decline in hospital autopsy [

6] and an increased interest in forensic autopsy. This underlines how our society has an interest in the legal aspect rather than in knowing the cause of death.

For this purpose, in our study, we aimed to analyze 645 hospital autopsy cases from 2006 to 2021 retrieved from the digital archive of the Pathology Unit, Department of Precision and Regenerative Medicine and Ionian Area, Polyclinic of Bari, to study the rate of concordance between clinical and autopsy diagnosis and evaluating whether the execution of hospital autopsies is helpful in the modern age.

Material and Methods

In our retrospective observational study, we analyzed the autopsy case history of the Pathology Unit, Department of Precision and Regenerative Medicine and Ionian Area, Polyclinic of Bari.

We used the digitalized archive of autopsy reports between 2006 and 2021 for a total of 645 case and all cases in the archive were included in the study.

The 645 cases were divided into groups of four years: group A: 2006-2009 of 174 cases, group B: 2010-2013 of 119 cases,group C: 2014-2017 of 168 cases, and group D: 2018-2021 of 184 cases.

Each subgroups was divided by age: fetus < 180 days or < 6 months gestational age, infant/ newborn 1 year of age, child/adolescent 1-16 years of age, and adult >16 years of age.

Divided into subgroups: gender, age, specialty, autopsy diagnosis, and correlation between clinical and autopsy diagnosis.

Analysing the pathological diagnosis, we grouped the cause of death into: cardiovascular, infectious, miscellaneous, neoplastic, placental, pulmonary, and syndromes/malformations.

Finally, we analyzed the discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses.

Results

Group A

In group A, it was observed that out of 174 cases, 58% were male, 41% female, and 1% undefined, of which 58% were adults, 1% children, 29% infants, and 12% fetuses.

Out of these 174, th specialty were: neonatology 55%, gynecology 19%, internal medicine 10%, external 7%, and other departments 9%.

The cause of death was classified as pulmonary disease in 23%, syndromes and/or malformations 10%, infections 8%, cardiovascular diseases 6%, placental disease 4%, neoplasms 4%, and miscellaneous 45%.

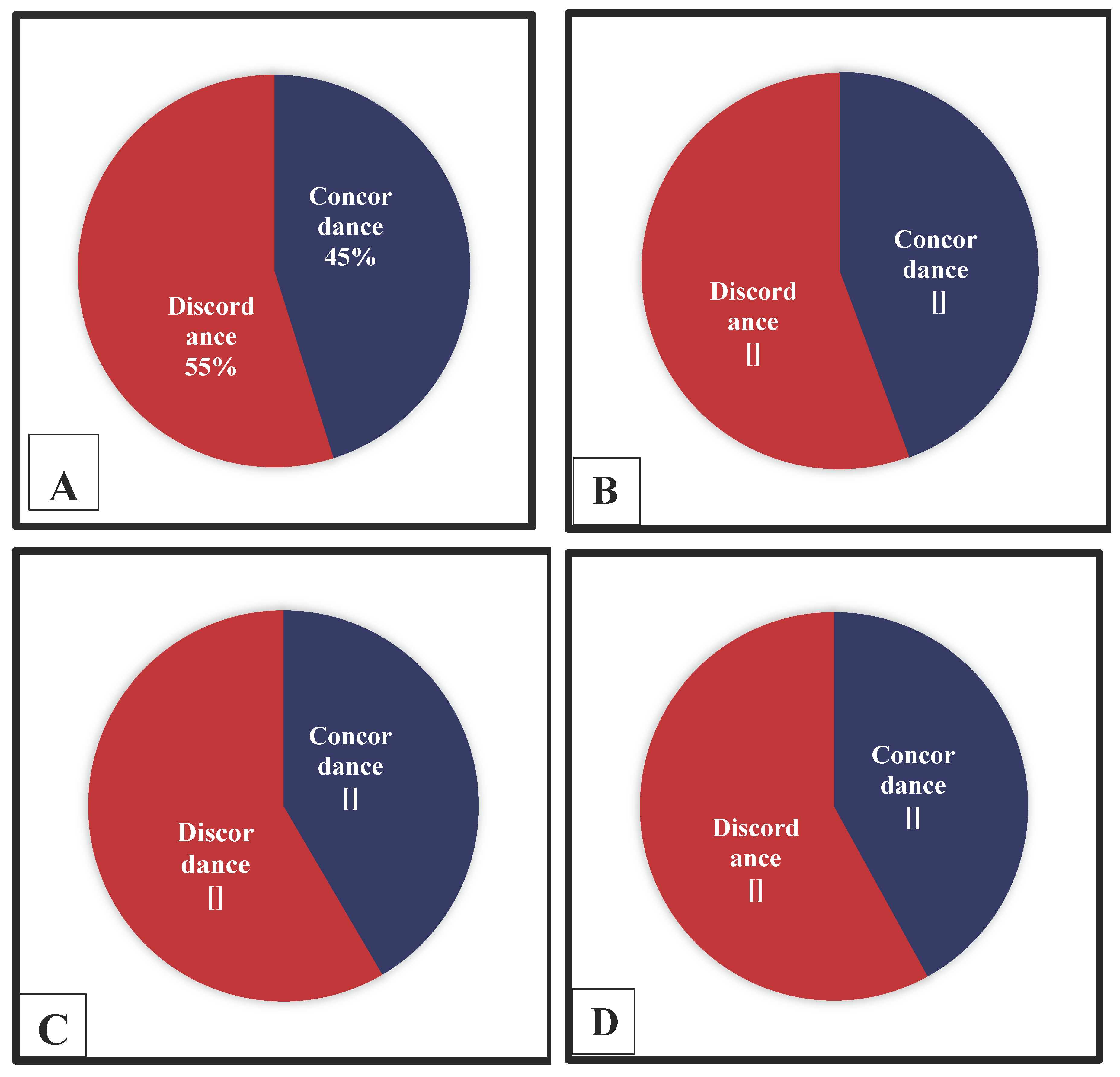

In 55% of the analyzed cases there was discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses (

Figure 1 – A).

Group B

In group B comprised 119 cases; 51% male, 48% female, and 1% undefined; of which 31% were adults, 6% children, 46% infants, and 17% fetuses.

The specialty of the origin of the deceased was 48% neonatology, 19% gynecology, 10% cardiac surgery, 12% general surgery, 4% neurology, and 7% others.

The cause of death was categorized as 25% pulmonary diseases, 15% cardiovascular diseases, 11% syndromes and/or malformations, 9% infectious diseases, 3% neoplasms, 1% placental pathology, and finally with 36% miscellaneous.

In 56% of the cases a discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses was observed (

Figure 1 – B).

Group C

In group C comprised 168 cases, out of which 50% were male and 50% female; 26% were adults, 1% were children, 37% infants, and 36% fetuses. The origin of the deceased was 30% gynecology, 25% neonatology, 17% cardiac surgery, 6% emergency room, 5% general surgery, 4% from other regional hospitals, and 13% others.

The cause of death was classified as 24% pulmonary diseases, 15% cardiovascular diseases, 11% syndromes and/or malformations, 6% placental pathology, 3% infections, 2% neoplasms, and finally 39% as miscellaneous.

In 58% of the cases there was a discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses (

Figure 1 – C).

Group D

In group D comprised 184 cases; 56% male, 43% female, and 1% undefined; 38% were adults, 3% children, 26% infants, and 33% fetuses.

Of these 184 cases, the specialty of origin was 32% gynecology, 21% other regional hospitals, 21% neonatology, 14% emergency department, and 12% others.

In most patients, the cause of death involved pulmonary diseases 27%, 23% cardiovascular diseases, 6% syndromes and/or malformations, 5% placental disease, 4% infections, 2% neoplasms, and 33% miscellaneous.

In 58% of the cases there was discrepancy between clinical and pathological diagnoses (

Figure 1 – D).

Discussion and Literature Review

Analyzing the 645 hospital autopsies, we observed a clear predominance of males, especially among infants and fetuses, and the most frequent specialty of origin was neonatology. The cause of death in our study was primarily pulmonary diseases followed by cardiovascular diseases, and the discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses was over 56.75%.

Our study highlights that hospital autopsies were performed mainly in fetuses and infants, and the requirement of autopsy in adults was reduced.

The reduction in hospital autopsies in adult patients is probably due to the excessive trust in medical diagnostic technology, whereby it is believed that the autopsy does not provide any additional information that is not already known at the time of death [

7].

Although some studies have underlined the importance of carrying out a hospital autopsy [

6,

7,

8], very often the medical doctors do not recognize the importance and therefore do not explain the advantages to the deceased’s relatives.

Autopsy is a fundamental tool for understanding pathological processes, the effectiveness of treatments, the correct diagnostic approaches, and for preventing medical errors and supporting public health [

9,

10].

In a study conducted in Sweden by N. Friberg et al. on 2410 hospital autopsies of adult patients they observed an overall reduction in the request for autopsy examination with prevalence of cardiovascular disease as the cause of death, and with a discrepancy of > 30% between clinical diagnosis and autopsy [

11]. They highlighted how the hospital autopsy provides information about the disease and cause of death that is likely unknown to the doctor and presumably to the relatives of the deceased, and how this can have a negative impact on public health [

11,

12].

B. G. H. Latten et al. in a prospective cohort study investigated the relationship between clinical cause of death, a history of cancer, and the rate of medical autopsies, and observed that the autopsy rate was positively correlated with the number of causes of death suggesting a higher value of interest in autopsies in complex medical cases [

13]. According to the authors, healthcare and individuals would benefit from an increase in post-mortem investigations [

13].

In their study M. O’Rahelly et al. observed a 40% reduction in the autopsy rate [

14] and other studies in the literature [

15,

16,

17].

One factor that can have a positive influence on the phenomenon of reducing the performance of hospital autopsies is the communication by the doctor of the importance of the autopsy to provide clarification of the cause of death [

18], especially in sudden death in foetuses, infants and young people, from cardiac or non-cardiac causes and from genetic or non-cardiac causes.

In addition, it is important to underline that stillbirth represents a dramatic experience, not only for parents, but also for professionals, especially if it occurs in the last weeks of gestation.

Therefore it is clear that the hospital autopsy is still useful in the modern age, to evaluate the clinical diagnostic accuracy, and above all for fetuses and newborns to be able to examine the various causes of death, both genetic and otherwise, and to be able to help future parents for the subsequent pregnancies [

19].

From a public health perspective, the autopsy can become a preventive tool for family members and the community, and play a role in grieving [

20].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study of hospital autopsies at the Polyclinic of Bari shows that the discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnosis is 56.75%.

Moreover, the hospital autopsy is still useful in the modern age, especially for the diagnosis of fetal and neonatal pathology, so that genetic and non-genetic diagnoses can be studied to help future parents for subsequent pregnancies.

Focusing on the problems of stillbirth means ensuring adequate support for mothers and relatives, who are all too often left alone to face this dramatic event.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S. and R.B.; methodology, C.S. and R.B.; investigation, C.S.and G.C.; data curation, C.S. and GC; writing—original draft preparation, C.S. and R.B.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and G.I.; supervision, A.M. and G.I.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The project was approved by an institutional ethics committee. For human subjects, the investigation was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all family members of the subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cambiaghi M. Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564). J Neurol. 2017 Aug;264(8):1828-1830. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh SK. Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771): father of pathologic anatomy and pioneer of modern medicine. Anat Sci Int. 2017 Jun;92(3):305-312. [CrossRef]

- Prichard R. Selected items from the history of pathology: karl von rokitansky (1804-1878). Am J Pathol. 1979 Nov;97(2):276.

- Tan SY, Brown J. Rudolph Virchow (1821-1902): “pope of pathology”. Singapore Med J. 2006 Jul;47(7):567-8.

- Magnon R. Maurice Letulle (1853-1929) [Maurice Letulle (1853-1929]. Rev Infirm. 2009 Jan-Feb;(147):45. French.

- Sblano S, Arpaio A, Zotti F, Marzullo A, Bonsignore A, Dell’Erba A. Discrepancies between clinical and autoptic diagnoses in Italy: evaluation of 879 consecutive cases at the “Policlinico of Bari” teaching hospital in the period 1990-2009. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2014;50(1):44-8. [CrossRef]

- Scarl R, Parkinson B, Arole V, Hardy T, Allenby P. The hospital autopsy: the importance in keeping autopsy an option. Autops Case Rep. 2022 Feb 17;12:e2021333. [CrossRef]

- Hamza A. Perception of pathology residents about autopsies: results of a mini survey. Autops Case Rep. 2018 Apr 18;8(2):e2018016. [CrossRef]

- Esteban A, Fernández-Segoviano P. The autopsy as a tool to monitor diagnostic error. Intensive Care Med. 1999 Apr;25(4):343-4. [CrossRef]

- Xiao J, Krueger GR, Buja LM, Covinsky M. The impact of declining clinical autopsy: need for revised healthcare policy. Am J Med Sci. 2009 Jan;337(1):41-6. [CrossRef]

- Friberg N, Ljungberg O, Berglund E, Berglund D, Ljungberg R, Alafuzoff I, Englund E. Cause of death and significant disease found at autopsy. Virchows Arch. 2019 Dec;475(6):781-788. [CrossRef]

- Veress B, Alafuzoff I (1994) A retrospective analysis of clinical diagnoses and autopsy findings in 3,042 cases during two different time periods. Human Pathology 25(2):140–145. [CrossRef]

- Latten BGH, Kubat B, van den Brandt PA, Zur Hausen A, Schouten LJ. Cause of death and the autopsy rate in an elderly population. Virchows Arch. 2023 Dec;483(6):865-872. [CrossRef]

- O’Rahelly M, McDermott M, Healy M. Autopsy and pre-mortem diagnostic discrepancy review in an Irish tertiary PICU. Eur J Pediatr. 2021 Dec;180(12):3519-3524. Erratum in: Eur J Pediatr. 2021 Jul 27. [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom P, Janzon L, Sternby NH (1997) Declining autopsy ratein Sweden: a study of causes and consequences in Malmo. Sweden J Intern Med 242(2):157–165.

- Latten BGH, Overbeek LIH, Kubat B, ZurHausen A, Schouten LJ (2019) A quarter century of decline of autopsies in the Netherlands. Eur J Epidemiol 34(12):1171–1174.

- Turnbull A, Osborn M, Nicholas N (2015) Hospital autopsy: endangered or extinct? J Clin Pathol 68(8):601–604.

- Vignau A, Milikowski C. The autopsy is not dead: ongoing relevance of the autopsy. Autops Case Rep [Internet]. 2023;13:e2023425. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Cheng C, Zheng F, Saiyin H, Zhang P, Zeng W, Liu X, Liu G. An audit of autopsy-confirmed diagnostic errors in perinatal deaths: What are the most common major missed diagnoses. Heliyon. 2023 Sep 9;9(9):e19984. [CrossRef]

- McPhee SJ, Bottles K, Lo B, et al. To redeem them from death. Reactions of family members to autopsy. Am J Med. 1986;80(4):665-71. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).