Submitted:

16 February 2024

Posted:

19 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

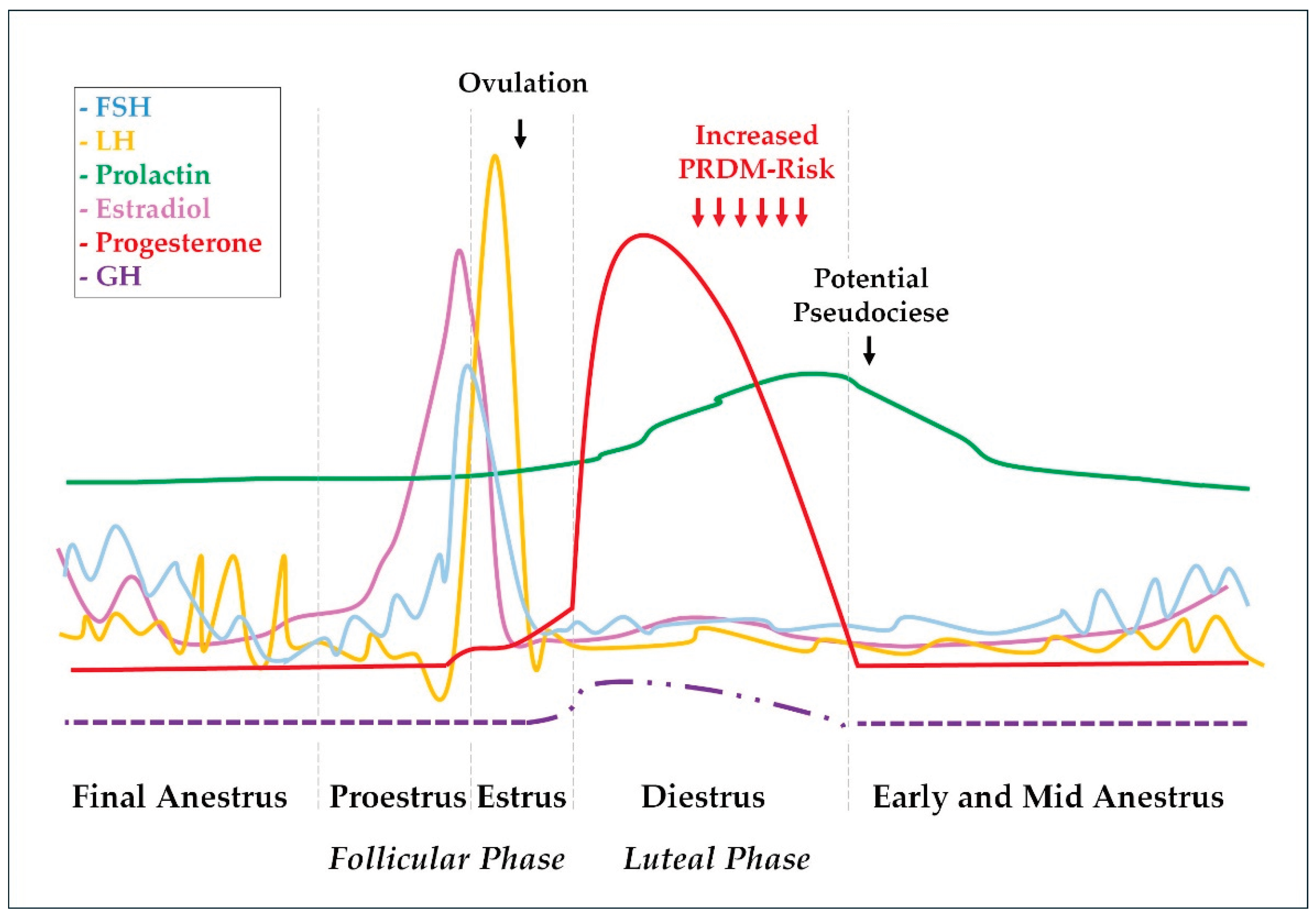

2. Canine Estrus Cycle: The Progesterone Perspective

Estrus’ cycle effects on mammary glands

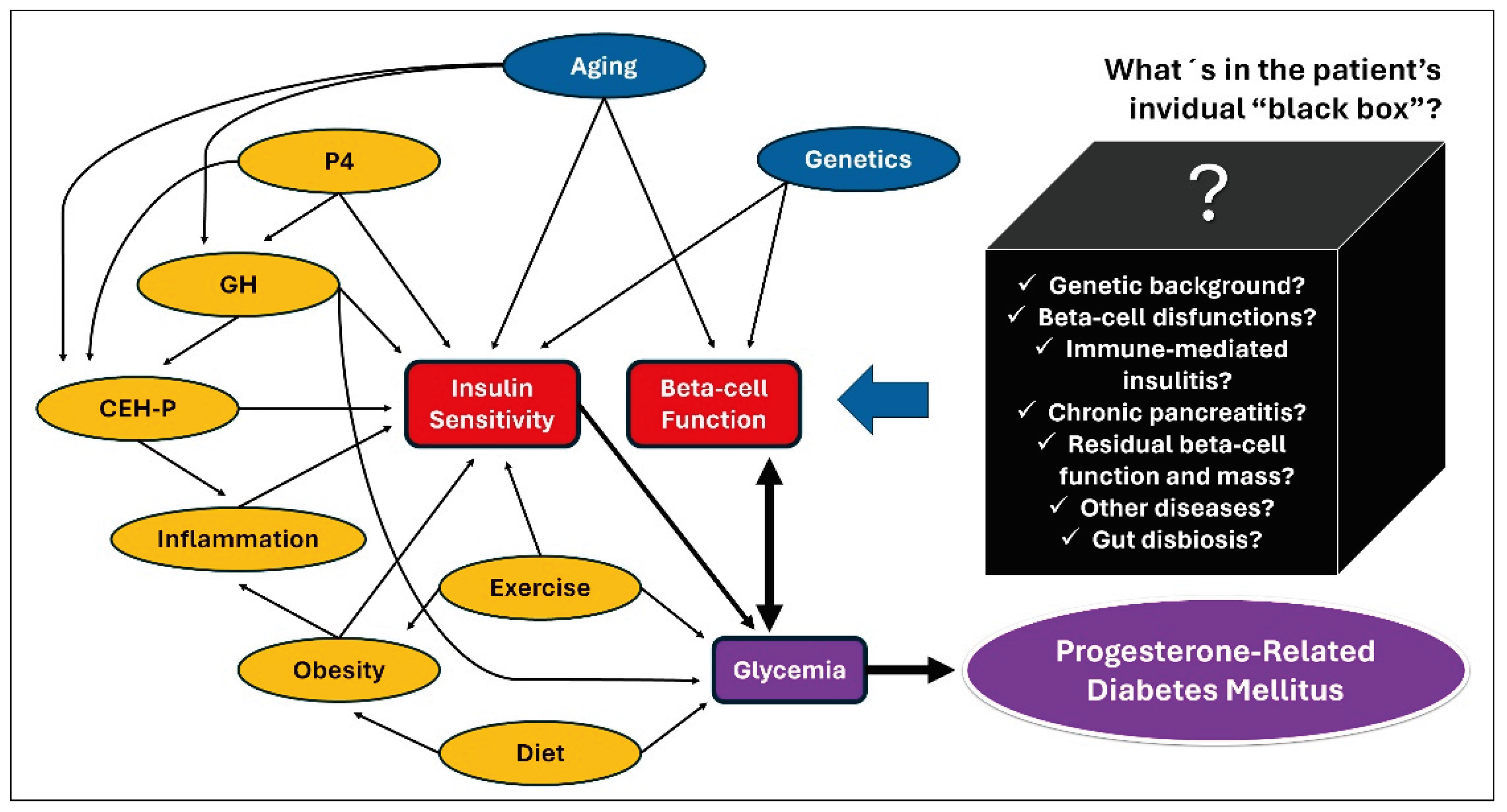

3. Diabetes Mellitus and the Estrus cycle effects on Insulin Sensitivity

3.1. Progesterone: The evil one?

3.2. How Growth Hormone Causes Insulin Resistance?

3.3. Do estrogens play a role in insulin sensitivity?

3.4. Estrus cycle effects on markers of insulin sensitivity.

4. Pyometra and its impact on insulin sensitivity

5. How to Best Manage Progesterone-Related CDM?

5.1. Initial patient evaluation

5.2. Treatment goals and recommendations

5.3. When surgery is indicated?

5.4. What are the next steps after surgery?

5.5. What to do when spaying is not an option?

5.6. Appliable Preventive Measures

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilor, C.; Niessen, S.J.M.; Furrow, E.; DiBartola, S.P. What’s in a name? Classification of diabetes mellitus in veterinary medicine and why it matters. J Vet Intern Med 2016, 30, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O´Kell, A.L.; Davison, L.J. Etiology and pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus in dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2023, 53, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.A. The treatment and control of diabetes in the dog. Aust Vet J 1958, 34, 222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.S. Spontaneous diabetes mellitus. Vet Rec 1960, 72, 548–554. [Google Scholar]

- Pöppl, A.G.; de Carvalho, G.L.C.; Vivian, I.F.; Corbellini, L.G.; González, F.H.D. Canine diabetes mellitus risk factors: A matched case-control study. Res Vet Sci 2017, 114, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeley, A.M.; Brodbelt, D.C.; O'Neill, D.G.; Church, D.B.; Davison, L.J. Assessment of glucocorticoid and antibiotic exposure as risk factors for diabetes mellitus in selected dog breeds attending UK primary-care clinics. Vet Rec 2023, 192, e2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pöppl, A.G.; González, F.H.D. Epidemiologic and clinical-pathological features of canine diabetes mellitus. Acta Scien Veterin 2005, 33, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Casillas, Y.; Melián, C.; Holder, A.; Wiebe, J.C.; Navarro, A.; Quesada-Canales, O.; Expósito-Montesdeoca, A.B.; Catchpole, B.; Wägner, A.M. Studying the heterogeneous pathogenesis of canine diabetes: Observational characterization of an island population. Vet Med Sci 2021, 7, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleeman, L.; Barrett, R. Cushing’s syndrome and other causes of insulin resistance in dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2023, 53, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fall, T.; Kreuger, S.J.; Juberget, A.; Bergström, A.; Hedhammar, A. Gestational diabetes mellitus in 13 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2008, 22, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fall, T.; Hedhammar, A.; Wallberg, A.; Fall, N.; Ahlgren, K.M.; Hamlin, H.H.; Lindblad-Toh, K.; Andersson, G.; Kämpe, O. Diabetes mellitus in elkhounds is associated with diestrus and pregnancy. J Vet Intern Med 2010, 24, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagman, R. Pyometra in Small Animals 3.0. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2023, 53, 1223–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krook, L.; Larsson, S.; Rooney, J.R. The interrelationship of diabetes mellitus, obesity, and pyometra in the dog. Am J Vet Res 1960, 21, 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Pöppl, A.G.; Mottin, T.S.; González, F.H.D. Diabetes mellitus remission after resolution of inflammatory and progesterone-related conditions in bitches. Res Vet Sci 2013, 94, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöppl, A.G.; Lasta, C.S.; González, F.H.D.; Kucharski, L.C.; Da Silva, R.S.M. Insulin sensitivity indexes in female dogs: Effect of estrus cycle and pyometra. Acta Scien Veterin. 2009, 37, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöppl, A.G.; Valle, S.C.; Mottin, T.S.; Leal, J.S.; González, F.H.D.; Kucharski, L.C.; Da Silva, R.S.M. Pyometra-associated insulin resistance assessment by insulin binding assay and tyrosine kinase activity evaluation in canine muscle tissue. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2021, 76, 106626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöppl, A.G.; Valle, S.C.; González, F.H.D.; Beck, C.A.C.; Kucharski, L.C.; Da Silva, R.S.M. Estrus cycle effect on muscle tyrosine kinase activity in bitches. Vet Res Comm 2012, 36, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöppl, A.G.; Valle, S.C.; González, F.H.D.; Kucharski, L.C.; Da Silva, R.S.M. Insulin binding characteristics in canine muscle tissue: Effects of the estrous cycle phases. Pesq Vet Bras 2016, 36, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concannon, P.W. Reproductive cycles of the domestic bitch. Anim Reprod Sci 2011, 124, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concannon, P.W. Endocrinologic control of normal canine ovarian function. Reprod Dom Anim 2009, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.C.; Nelson, R.W. Canine and Feline Endocrinology and Reproduction, 3rd ed.; Saunders, Missouri, USA, 2004; pp. 752-774.

- Hoffmann, B.; Riesenbeck, A.; Klein, R. Reproductive endocrinology of bitches. Anim Reprod Sci 1996, 42, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinshead, F.K.; Hanlon, D.W. Normal progesterone profiles during estrus in the bitch: A prospective analysis of 1420 estrous cycles. Theriogenology 2019, 125, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, K. Canine vaginal cytology during the estrous cycle. Can Vet J 1985, 26, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Cruchten, S.; Van den Broeck, W.; D’haeseleer, M.; Simoens, P. Proliferation patterns in the canine endometrium during the estrous cycle. Theriogenology 2004, 62, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, P. Progesterone and the progesterone receptor. J Reprod Med 1999, 44, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thompson, F.N. Reprodução em mamíferos do sexo feminino. In Dukes: Fisiologia dos Animais Domésticos, 2nd ed.; Reece, W.O. Ed, Guanabara Koogan; Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2006; volume 1, pp. 644-669.

- Concannon, P.W.; Hansel, W.; Visek, W.J. The ovarian cycle of the bitch: Plasma estrogen, LH and progesterone. Biol Reprod 1975, 13, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooistra, H.S.; Okkens, A.C. Secretion of growth hormone and prolactin during progression of the luteal phase in healthy dogs: a review. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2002, 197, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobello, C. Revisiting canine pseudocyesis. Theriogenology 2021, 167, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, P.J.; Mol, J.A.; Rutterman, G.R.; Rijnberk, A. Progestin-induced growth hormone excess in the dog originates in the mammary gland. Endocrinology 1994, 134, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eingenmann, J.E.; Eingenmann, R.Y.; Rijinberk, A.; Van der Gaag, I.; Zapf, J.; Froesch, E.R. Progesterone-controlled growth hormone overproduction and naturally occurring canine diabetes and acromegaly. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1983, 104, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cock, H.; Ducatelle, R.; Tilmant, K.; De Schepper, J. Possible role for insulin-like growth factor-I in the pathogenesis of cystic endometrial hyperplasia pyometra complex in the bitch. Theriogenology 2002, 57, 2271–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, F.P.; Argentino, D.P.; Muñoz, M.C.; Miquet, J.G.; Sotelo, A.I.; Turyn, D. Influence of the crosstalk between growth hormone and insulin signaling on the modulation of insulin sensitivity. Growth Horm IGF Res 2005, 15, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvêa, F.N.; Pennacchi, C.S.; Assaf, N.D.; Branco, L.O.; Costa, P.B.; Reis, P.A.; Borin-Crivellenti, S. Acromegaly in dogs and cats. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2021, 82, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, S.J.M.; Bjornvad, C.; Church, D.B.; Davison, L.; Esteban-Saltiveri, D.; Fleeman, L.M.; Forcada, Y.; Fracassi, F.; Gilor, C.; Hanson, J.; Herrtage, M.; Lathan, P.; Leal, R.O.; Loste, A.; Reusch, C.; Schermerhorn, T.; Stengel, C.; Thoresen, S.; Thuroczy, J. Agreeing Language in Veterinary Endocrinology (ALIVE): diabetes mellitus – a modified Delphi-method-based system to create consensus disease definitions. Vet J 2022, 105910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Fleeman, L.M.; Wilson, B.J.; Mansfield, C.S.; McGreevy, P. Epidemiological study of dogs with diabetes mellitus attending primary care veterinary clinics in Australia. Vet Rec 2020, 187, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, L.J.; Herrtage, M.E.; Catchpole, B. Study of 253 dogs in the United Kingdom with diabetes mellitus. Vet Rec 2005, 156, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassi, F.; Pietra, M.; Boari, A.; Aste, G.; Giunti, M.; Famigli-Bergamini, P. Breed distribution of canine diabetes mellitus in Italy. Vet Res Commun 2004, 28, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guptill, L.; Glickman, L.; Glickman, N. Time trends and risk factors for diabetes mellitus in dogs: analysis of veterinary medical database records (1970-1999). Vet J 2003, 165, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattin, M.; O'Neill, D.; Church, D.; McGreevy, P.D.; Thomson, P.C.; Brodbelt, D. An epidemiological study of diabetes mellitus in dogs attending first opinion practice in the UK. Vet Rec 2014, 174, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiles, B.M.; Llewellyn-Zaidi, A.M.; Evans, K.M.; O’Neill, D.G.; Lewis, T.W. Large-Scale survey to estimate the prevalence of disorders for 192 Kennel Club registered breeds. Canine Genet Epidemiol 2017, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fall, T.; Hamlin, H.H.; Hedhammar, A.; Kampe, O.; Egenvall, A. Diabetes mellitus in a population of 180,000 insured dogs: incidence, survival, and breed distribution. J Vet Intern Med 2007, 21, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleeman, L.M.; Rand, J.S. Management of canine diabetes. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2001, 31(5), 855–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catchpole, B.; Ristic, J.M.; Fleeman, L.M.; Davison, L.J. Canine diabetes mellitus: can old dogs teach - us new tricks? Diabetologia 2005, 48, 1948–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.W. Canine diabetes mellitus. In: Canine and Feline Endocrinology, 4th ed.; Feldman, E.C.; Nelson, R.W.; Reusch, C.E.; Scott-Moncrieff, J.C.R.; Behrend, E.N. Eds.; Saunders, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 2015. 213-257.

- Mui, M.L.; Famula, T.R.; Henthorn, P.S.; Hess, R.S. Heritability and complex segregation analysis of naturally-occurring diabetes in Australian Terrier Dogs. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.V.; Famula, T.R.; Oberbauer, A.M.; Hess, R.S. Heritability and complex segregation analysis of diabetes mellitus in American Eskimo Dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2019, 33, 1926–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, A.L.; Massey, J.P.; Davison, L.J.; Ollier, W.E.R.; Catchpole, B.; Kennedy, L.J. Dog leucocyte antigen (DLA) class II haplotypes and risk of canine diabetes mellitus in specific dog breeds. Canine Med Genet 2020, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringstad, N.K.; Lingaas, F.; Thoresen, S.I. Breed distributions for diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism in Norwegian dogs. Canine Med Genet 2022, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, T.; Koffler, M.; Helderman, J.H.; Prince, D.; Thirlby, R.; Inman, L.; Unger, R.H. Severe diabetes induced in subtotally depancreatized dogs by sustained hyperglycemia. Diabetes 1988, 37, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.W.; Reusch, C.E. Animal model of disease Classification and etiology of diabetes in dogs and cats. J Endocrinology 2014, 222, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renauld, A.; Sverdlik, R.C.; Von Lawzewitsch, I.; Agüero, A.; Pérez, R.L.; Rodríguez, R.R.; Foglia, V.G. Metabolic and histological pancreatic changes induced by ovariectomy in the female dog. Acta Physiol Pharmacol Latinoam 1987, 37, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sasidharan, J.K.; Patra, M.K.; Singh, L.K.; Saxena, A.C.; De, U.K.; Singh, V.; Mathesh, K.; Kumar, H.; Krishnaswamy, N. Ovarian Cysts in the Bitch: An Update. Top Companion Anim Med 2021, 43, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farges, A.; Crawford, D.; Silva, C.A.; Ramsey, I. Hyperprogesteronism associated with adrenocortical tumours in two dogs. Vet Rec Case Rep 2024, e794, 1–9, (online ahead of print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, C.C.; Aglione, L.N.; Smith, M.S.; Lacy, D.B.; Moore, M.C. Insulin action during late pregnancy in the conscious dog. Am J Physiol, Endocrinol Metab 2004, 286, E909–9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, M.A.; Carpenter, M.W.; Coustan, D.R. Screening and diagnosis of gestacional diabetes mellitus. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2007, 50(4), 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo. G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Gaglia, J.S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Isaacs, D.; Johnson, E.L.; Kahan, S.; Khunti, K.; Leon, J.; Lyons, S.K.; Perry, M.L.; Prahalad, P.; Pratley, R.E.; Seley, J.J.; Stanton, R.C.; Gabbay, R.A. American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46(Suppl. 1):S19–S40. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C.; Ursing, D.; Törn, C.; Aberg, A.; Landin-Olsson, M. Presence of GAD antibodies during gestational diabetes mellitus predicts type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007, 30(8), 1968–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNinni, A.; Hess, R.S. Development of a requirement for exogenous insulin treatment in dogs with hyperglycemia. J Vet Intern Med 2024, 1-7 (online ahead of print). [CrossRef]

- Watanake, R.M.; Black, M.H.; Xiang, A.H.; Allayee, H.; Lawrence, J.M.; Buchanan, T.A. Genetics of gestational diabetes mellitus and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007, 30(2suppl), S134–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beischer, N.A.; Oats, J.N.; Henry, O.A.; Sheedy, M.T.; Walstab, J.E. Incidence and severity of gestational diabetes mellitus according to country of birth in woman living in Australia. Diabetes 1991, 40(2suppl), 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.Y.; Callagan, W.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Schmid, C.H.; Lau, J.; England, L.J.; Dietz, P.M. Maternal obesity and risk of gestacional diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007, 30(8), 2070–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wejdmark, A.K.; Bonnet, B.; Hedhammar, A.; Fall, T. Lifestyle risk factors for progesterone-related diabetes mellitus in Elkhounds – a case-control study. J Small Anim Pract 2011, 52, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampman, U.; Knorr, S.; Fuglsang, J.; Ovesen, P. Determinants of Maternal Insulin Resistance during Pregnancy: An Updated Overview. J Diabetes Res 2019, 5320156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.A. High-risk pregnancy and hypoluteoidism in the bitch. Theriogenology 2008, 70(9), 1424–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.A. Glucose homeostasis during canine pregnancy: insulin resistance, ketosis, and hypoglycemia. Theriogenology 2008, 70(9), 1418–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Berger, D.K.; Chamany, S. Recurrence of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007, 30(5), 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philips, P.J. Gestational diabetes: Worth finding and actively treating. Aust Fam Physician 2006, 35(9), 701–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, E.A.; Enns, L. Role of gestational hormones in the induction of insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrionol Metab 1988, 67(2), 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, T.; Hori, S.; Sugiyama, M.; Fujisawa, E.; Nakano, T.; Tsuneki, H.; Nagira, K.; Saito, S.; Sasaoka, T. Progesterone inhibits glucose uptake by affecting diverse steps of insulin signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010, 298(4), E881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.R.; Choi, W.; Heo, J.H.; Huh, J.; Kim, G.; Lee, K.; Kwun, H.; Shin, H.; Baek, I.; Hong, E. Progesterone increases blood glucose via hepatic progesterone receptor membrane component 1 under limited or impaired action of insulin. Sci Rep 2020, 10(1), 16316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, J.S.; Fleeman, L.M.; Farrow, H.A.; Appleton, D.J.; Lederer, R. Canine and feline diabetes mellitus: nature or nurture? J Nutr 2004, 134(8), 2072S–2080S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mared, M.; Catchpole, B.; Kämpe, O.; Fall, T. Evaluation of circulating concentrations of glucose homeostasis biomarkers, progesterone, and growth hormone in healthy Elkhounds during anestrus and diestrus. Am J Vet Res 2012, 73(2), 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strage, E.M.; Lewitt, M.S.; Hanson, J.M.; Olsson, U.; Norrvik, F.; Lilliehöök, I.; Holst, B.S.; Fall, T. Relationship among Insulin Resistance, Growth Hormone, and Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Concentrations in Diestrous Swedish Elkhounds. J Vet Intern Med 2014, 28, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramal, J.D.; Renauld, A.; Gómez, N.V.; Garrido, D.; Wanke, M.M.; Marquez, A.G. Natural estrous cycle in normal and diabetic bitches in relation to glucose and insulin tests. Medicina (B Aires) 1997, 57, 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Renauld, A.; Sverdlik, R.C.; Agüero, A.; Pérez, R.L. Influence of estrogen-progesterone sequential administration on pancreas cytology. Serum insulin and metabolic adjustments in female dogs. Acta Diabetol Lat 1990, 27(4), 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijnberk, A.D.; Kooistra, H.S.; Mol, J.A. Endocrine diseases in dogs and cats: similarities and differences with endocrine diseases in humans. Growth Horm IGF Res 2003, 13, S158–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kopchick, J.J.; Puri, V.; Sharma, V.M. Effect of growth hormone on insulin signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2020, 1, 518:111038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, D.; Flier, J.S. Insulin resistance. Mechanisms, syndromes, and implications. N Engl J Med 1991, 325(13), 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, A.R.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin signaling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature 2001, 414(6865), 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooistra, H.S.; Den Hertog, E.; Okkens, A.C.; Mol, J.A.; Rijnberk, A. Pulsatile secretion pattern of growth hormone during the luteal phase and mild-anoestrus in beagle bitches. J Reprod Fertil 2000, 119(2), 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Godsland, I.F. Oestrogens and insulin secretion. Diabetologia 2005, 48(11), 2213–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paoli, M.; Zakharia, A.; Werstuck, G.H. The role of estrogen in insulin resistance: A review of clinical and preclinical data. Am J Pathol 2021, 191(9), 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renauld, A.; Von Lawzewitsch, I.; Pérez, R.L.; Sverdlik, R.; Agüero, A.; Foglia, V.G.; Rodríguez, RR. Effect of estrogens on blood sugar, serum insulin and serum free fatty acids, and pancreas cytology in female dogs. Acta Diabetol Lat 1983, 20(1), 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, R.P.A.; Machado, U.F.; Warmer, M.; Gostafsson, J. Muscle GLUT4 regulation by estrogen receptors ERβ and ERα. PNAS 2006, 103(5), 1605–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, H.; Kurachi, H.; Nishio, Y.; Takeda, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Adachi, K.; Morishige, K.; Ohmichi, M.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Murata, Y. Estrogen suppresses transcription of lipoprotein lipase gene. Existence of a unique estrogen response element on the lipoprotein lipase promoter. J Biol Chem 2000, 275(15), 11404–11411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, A.M.; Barros, R.P.A.; Zampieri, R.A.; Okamoto, M.M.; Carvalho Papa, P.; Machado, U.F. Abnormal subcellular distribution of GLUT4 protein in obese and insulin-treated diabetic female dogs. Braz J Med Biol Res 2004, 37(7), 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Roux, P.H.; Van Der Walt, L.A. Ovarian autograft as an alternative to ovariectomy in bitches. J S Afr Vet Assoc 1977, 48(2), 117–123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vendramini, T.H.A.; Amaral, A.R.; Pedrinelli, V.; Zafalon, R.V.A.; Rodrigues, R.B.A.; Brunetto, M.A. Neutering in dogs and cats: current scientific evidence and importance of adequate nutritional management. Nutr Res Rev 2020, 33(1), 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, T.M.; Levy, J.C.; Matthews, D.R. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 2004, 27(6), 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ader, M.; Stefanovski, D.; Richey, J.M.; Kim, S.P.; Kolka, C.M.; Ionut, V.; Kabir, M.; Bergman, R.N. Failure of homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance to detect marked diet-induced insulin resistance in dogs. Diabetes 2014, 63(6), 1914–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, A. Endocrine emergencies in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2013, 43(4), 869–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkest, K.R.; Fleeman, L.M.; Rand, J.S.; Morton, J.M. Basal measures of insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion and simplified glucose tolerance tests in dogs. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2010, 39(3), 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuta, H.; Mori, A.; Urumuhan, N.; Lee, P.; Oda, H.; Saeki, K.; Kurishima, M.; Nozawa, S.; Mizutani, H.; Mishina, S.; Arai, T.; Sako, T. Characterization and comparison of insulin resistance induced by Cushing syndrome or diestrus against healthy control dogs as determined by euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic glucose clamp profile glucose in- fusion rate using an artificial pancreas apparatus. J Vet Med Sci 2012, 74(11), 1527–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailhache, E.; Nguyen, P.; Krempf, M.; Siliart, B.; Magot, T.; Ougueram, K. Lipoproteins abnormalities in obese insulin-resistant dogs. Metabolism 2003, 52(5), 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renauld, A.; Gomez, N.V.; Scaramal, J.D.; Garrido, D.; Wanke, M.M. Natural estrous cycle in normal and diabetic bitches. Basal serum total lipids and cholesterol. Serum tryglicerides profiles during glucose and insulin tests. Acta Physiol Pharmacol Ther Latinoam 1998, 48, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.C.; McKern, N.M.; Ward, C.W. Insulin receptor structure and its implications for the IGF-1 receptor. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2007, 17(6), 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, L.A.; McCurdy, C.E.; Hernandez, T.L.; Kirwan, J.P.; Catalano, P.M.; Friedman, J.E. Cellular mechanisms for insulin resistance in normal pregnancy and gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäffer, L. A model for insulin binding to the insulin receptor. Eur J Biochem 1994, 221(3), 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, V.; Frazzini, V.; Davidheiser, S.; Przybylski, R.J.; Kliegman, R.M. Insulin binding receptor number and binding affinity in newborn dogs. Pediatr Res 1991, 29, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanvitto, G.L.; Marques, M.; Dellacha, J.M.; Turyn, D. Masked insulin receptors in rat hypothalamus microsomes. Horm Metab Res 1994, I, 160–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, M.R.; Smith, M.S.; Snead, W.L.; Connolly, C.C.; Lacy, D.B.; Moore, M.C. Chronic estradiol and progesterone treatment in conscious dogs: ef- fects on insulin sensitivity and response to hypoglycemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2005, 289(4), R1064–R1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, E.N.; Winnick, J.J.; Edgerton, D.S.; Scott, M.F.; Smith, M.S.; Farmer, B.; Williams, P.E.; Cherrington, A.D.; Moore, M.C. Hepatic and whole-body insulin metabolism during proestrus and estrus in mongrel dogs. Comp Med 2016, 66, 235–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hagman, R. Canine pyometra: What is new? Reprod Domest Anim 2017, 52, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.O. Canine pyometra. Theriogenology 2006, 66(3), 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bosschere, H.; Ducatelle, R.; Vermeirsch, H.; Simoens, P.; Coryn, M. Estrogen-αand progesterone receptor expression in cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra in the bitch. Anim Reprod Sci 2002, 70, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagman, R. Pyometra in Small Animals. Vet Clin North Small Anim Pract 2018, 48(4), 639–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Chen, R.; Wang, H.; Liang, F. Mechanisms linking inflammation to insulin resistance. Int J Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, U.N. Current advances in sepsis and septic shock with particular emphasis on the role of insulin. Med Sci Monit 2003, 9, RA181–RA192. [Google Scholar]

- Das, U.N. Insulin in sepsis and septic shock. JAPI 2003, 51, 695–700. [Google Scholar]

- Grimble, R.F. Inflammatory status and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2002, 5, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R. Inflammatory mechanisms in the regulation of insulin resistance. Mol Med 2008, 14, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, A.J.; Hervera, M.; Hunter, L.; Holden, S.L.; Morris, P.J.; Biourge, V.; Trayhurn, P. Improvement in insulin resistance and reduction in plasma inflammatory adipokines after weight loss in obese dogs. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2009, 37, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakshlag, J.J.; Struble, A.M.; Levine, C.B.; Bushey, J.J.; Laflamme, D.P.; Long, G.M. The effects of weight loss on adipokines and markers of inflammation in Dogs. Br J Nutr 2011, 106, S11–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremias, J.T.; Takeara, P.; Vendramini, T.H.A.; Rodrigues, R.B.A.; Perini, M.P.; Pedrinelli, V.; Teixeira, F.A.; Brunetto, M.A.; Pontieri, C.F.F. Markers of inflammation and insulin resistance in dogs before and after weight loss versus lean healthy dogs. Pesq Vet Bras 2020, 40, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, P.H.; Vendramini, T.H.A.; Perini, M.P.; Zafalon, R.V.A.; Amaral, A.R.; Ochamotto, V.A.; Da Silveira, J.C.; Dagli, M.L.Z.; Brunetto, M.A. Obesity, inflammation, and cancer in dogs: Review and perspectives. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöppl, A.G.; Müller, F.; Queiroga, L.; González, F.H.D. Insulin resistance due to periodontal disease in an old diabetic female poodle. Diab Res Treat 2015, 2, 1–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivy, R.; Bar-Am, Y.; Retzkin, H.; Bruchim, Y.; Mazaki-Tovi, M. Preliminary evaluation of the impact of periodontal treatment on markers of glycaemic control in dogs with diabetes mellitus: A prospective, clinical case series. Vet Rec 2023, 194, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loste, A.; Marca, M.C. Study of the effect of total serum protein and albumin concentrations on canine fructosamine concentration. Can J Vet Res 1999, 63, 138–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pöppl, A.G. Canine diabetes mellitus: assessing risk factors to inform preventive measures. Vet Rec 2023, 192, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrend, E.; Holford, A.; Lathan, P.; Rucinsky, R.; Schulman, R. 2018 AAHA Diabetes Management Guidelines for Dogs and Cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2018, 54, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, J.A.; Garderen, E.V.; Selman, P.J.; Wolfswinkel, J.; Rijinberk, A.; Rutteman, G.R. Growth hormone mRNA in mammary gland tumors of dogs and cats. J Clin Invest 1995, 95, 2028–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, A.; Nishii, N.; Morita, T.; Yuki, M. GH-producing mammary tumors in two dogs with acromegaly. J Vet Med Sci 2012, 74, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staroňová, R.; Kožár, M.; Horňáková, L.; Fialkovičová, M. Diestrous diabetes mellitus remission in a Yorkshire terrier bitch. Vet Rec Case Rep 2021, 9, e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Bae, H.; Yu, D. A case of transient diabetes mellitus in a dog managed by ovariohysterectomy. J Biomed Transl Res. 2023, 24, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.M.; Kooistra, H.S.; Mol, J.A.; Dieleman, S.J.; Schaefers-Okkens, A.C. Ovariectomy during the luteal phase influences secretion of prolactin, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor-I in the bitch. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, R.S.; Jones, T. Anesthetic considerations in dogs and cats with diabetes mellitus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2023, 53, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilor, C.; Fleeman, L.M. One hundred years of insulin: Is it time for smart? J Small Anim Pract. 2022, 63, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiel, R.E.; Mooney, C.T. Insulins for the long-term management of diabetes mellitus in dogs: a review. Canine Med Genet 2022, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, F.A.; Brunetto, M.A. Nutritional factors related to glucose and lipid modulation in diabetic dogs: literature review. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci 2017, 54, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, F.A.; Machado, D.P.; Jeremias, J.T.; Queiroz, M.R.; Pontieri, C.F.F.; Brunetto, M.A. Effects of pea with barley and less-processed maize on glycaemic control in diabetic dogs. Br J Nutr 2018, 120, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, F.A.; Machado, D.P.; Jeremias, J.T.; Queiroz, M.R.; Pontieri, C.F.F.; Brunetto, M.A. Starch sources influence lipidaemia of diabetic dogs. BMC Vet Res 2020, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for Comparative Endocrinology. Available online: https://www.veterinaryendocrinology.org/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- van Bokhorst, K.L.; Galac, S.; Kooistra, H.S.; Valtolina, C.; Fracassi, F.; Rosenberg, D.; Meij, B.P. Evaluation of hypophysectomy for treatment of hypersomatotropism in 25 cats. J Vet Intern Med 2021, 35(2), 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, J.; Kenny, P.J.; Scudder, C.J.; Hazuchova, K.; Gostelow, R.; Fowkes, R.C; Forcada, Y.; Church, D.B.; Niessen, S.J.M. Efficacy of hypophysectomy for the treatment of hypersomatotropism-induced diabetes mellitus in 68 cats. J Vet Intern Med 2021, 35(2), 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostelow, R.; Scudder, C.J.; Keyte, S.; Forcada, Y.; Fowkes, R.C; Schmid, D.B.; Church, D.B.; Niessen, S.J.M. Pasireotide long-acting release treatment for diabetic cats with underlying hypersomatotropism. J Vet Inter Med 2017, 31(2), 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, D.D.; García, J.D.; Pompili, G.A.; Amunategui, J.P.R.; Ferraris, S.; Pignataro, O.M.; Guitelman, M. Cabergoline treatment in cats with diabetes mellitus and hypersomatotropism. J Feline Med Surg 2022, 24(12), 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aptekmann, K.P.; Schwartz, D.S. A survey of owner attitudes and experiences in managing diabetic dogs. Vet J 2011, 190, e122–e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aptekmann, K.P.; Armstrong, J.; Coradini, M.; Rand, J. Owner experiences in treating dogs and cats diagnosed with diabetes mellitus in the United States. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2014, 50, 247–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardo, A.M.; Baldo, D.F.; Dondi, F.; Pietra, M.; Chiocchetti, R.; Fracassi, F. Survival estimates and outcome predictors in dogs with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus treated in a veterinary teaching hospital. Vet Rec 2019, 185, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, A.; Odunayo, A. Diabetes Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Syndrome in Companion Animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2023, 53, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradini, S.; Pilosio, B.; Dondi, F.; Linari, G.; Testa, S.; Brugnoli, F.; Gianella, P.; Pietra, M.; Fracassi, F. Accuracy of a flash glucose monitoring system in diabetic dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2016, 30, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldo, D.F.; Fracassi, F. Continuous glucose monitoring in dogs and cats. Application of new technology to an old problem. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2023, 53, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, H.; Herbert, C.; Gilor, C. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of insulin detemir and insulin glargine 300 U/mL in healthy dogs. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2018, 64, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Samson, A.R.; Rand, J.; Ford, S.L. Detemir improves diabetic regulation in poorly controlled diabetic dogs with concurrent diseases. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2023, 261, 237–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, D.D.; Pignataro, O.P.; Castillo, V.A. Concurrent hyperadrenocorticism and diabetes mellitus in dogs. Res Vet Sci 2017, 115, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleeman, L.; Gilor, C. Insulin Therapy in Small Animals, Part 3: Dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2023, 53(3), 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzi, S.; Mazaki-Tovi, M.; Hershkovitz, S.; Yas, E.; Hess, R.S. Long-term field study of lispro and neutral protamine Hagedorn insulins treatment in dogs with diabetes mellitus. Vet Med Sci 2023, 9(2), 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niessen, S.J.M.; Powney, S.; Guitian, J.; Niessen, A.P.M.; Pion, P.D.; Shaw, J.A.M; Church, D.B. Evaluation of a Quality-of-Life Tool for Dogs with Diabetes Mellitus. J Vet Intern Med. 2012, 26, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baan, M.; Taverne, M.A.M.; Kooistra, H.S.; Gier, J.D.; Dieleman, S.J.; Okkens, A.C. Induction of parturition in the bitch with the progesterone-receptor blocker aglépristone. Theriogenology 2005, 63, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galac, S.; Kooistra, H.S.; Butinar, J.; Bevers, M.M.; Dieleman, S.J.; Voorhout, G.; Okkens, A.C. Termination of mid-gestation pregnancy in bitches with aglepristone, a progesterone receptor antagonist. Theriogenology 2000, 53, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binli, F.; Inan, I.; Büyükbudak, F.; Gram, A.; Kaya, D.; Liman, N.; Aslan, S.; Fındık, M.; Ay, S.S. The Efficacy of a 3-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Inhibitor for the Termination of Mid-Term Pregnancies in Dogs. Animals 2022, 12, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galac, S.; Kooistra, H.S.; Dieleman, S.J.; Cestnik, V.; Okkens, A.C. Effects of aglépristone, a progesterone receptor antagonist, administered during the early luteal phase in non-pregnant bitches. Theriogenology 2004, 62, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigliardi, E.; Bresciani, C.; Callegari, D.; Ianni, F.D.; Morini, G.; Parmigiani, E.; Bianchi, E. Use of aglepristone for the treatment of P4 induced insulin resistance in dogs. J Vet Sci 2014, 15, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.F.M.; Duchateau, L.; Okkens, A.C.; Vanham, L.M.L.; Mol, J.A.; Kooistra, H.S. Treatment of growth hormone excess in dogs with the progesterone receptor antagonist aglépristone. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemetayer, J.; Blois, S. Update on the use of trilostane in dogs. Can Vet J 2018, 59, 397–407. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, K.; Kooistra, H.S.; Galac, S. Treating canine Cushing’s syndrome: Current options and future prospects. Vet J 2018, 241, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gier, J.D; Wolthers, C.H.J.; Galac, S.; Okkens, A.C.; Kooistra, H.S. Effects of the 3-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor trilostane on luteal progesterone production in the dog. Theriogenology 2011, 75, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeukenne, P.; Verstegen, J. Termination of dioestrus and induction of oestrus in dioestrous nonpregnant bitches by the prolactin antagonist cabergoline. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 1997, 51, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Romagnoli, S.; Stelletta, C.; Milani, C.; Gelli, D.; Falomo, M.E.; Mollo, A. Clinical use of deslorelin for the control of reproduction in the bitch. Reprod Dom Anim 2009, 44 (Suppl. 2), 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadd, M.J.; Bienhoff, S.E.; Little, S.E.; Geller, S.; Ogne-Stevenson, J.; Dupree, T.J.; Scott-Moncrieff, J.C. Safety and effectiveness of the sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitor bexagliflozin in cats newly diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. J Vet Intern Med 2023, 37, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, M.R.; Graves, T.K. The Future of Diabetes Therapies New Insulins and Insulin Delivery Systems, Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Analogs, Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter Type 2 Inhibitors, and Beta Cell Replacement Therapy. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2023, 53, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauvais, W.; Cardwell, J. M.; Brodbelt, D. C. The effect of neutering on the risk of mammary tumours in dogs – a systematic review. J Small Anim Pract 2012, 53, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmunds, G.; Beck, S.; Kale, U.K.; Spasic, I.; O’Neill, D.; Brodbelt, B.; Smalley, M.J. Associations between dog breed and clinical features of mammary epithelial neoplasia in bitches: an Epidemiological Study of Submissions to a Single Diagnostic Pathology Centre Between 2008–2021. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2023, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundburg, C.R.; Belanger, J.M.; Bannasch, D.L.; Famula, T.R.; Oberbauer, A.M. Gonadectomy effects on the risk of immune disorders in the dog: a retrospective study. BMC Vet Res 2016, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urfer, S.R.; Kaeberlein, M. Desexing dogs: A review of the current literature. Animals 2019, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palestrini, C.; Mazzola, S.; Caione, B.; Groppetti, D.; Pecile, A.; Minero, M.; Cannas, S. Influence of Gonadectomy on Canine Behavior. Animals 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegram, C.; Raffan, E.; White, E.; Ashworth, A.H.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Church, D.B.; O'Neill, D.G. Frequency, breed predisposition and demographic risk factors for overweight status in dogs in the UK. J Small Anim Pract 2021, 62, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.L.; Hart, L.A.; Thigpen, A.P.; Willits, N.H. Assisting decision-making on age of neutering for 35 breeds of dogs: associated joint disorders, cancers, and urinary incontinence. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegram, C.; O’Neill, D.G.; Church†, D. B.; Hall, J.; Owen, L.; Brodbelt, D. C. Spaying and urinary incontinence in bitches under UK primary veterinary care: A case–control study. J Small Anim Pract 2019, 60, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiñeira, I.M.; Vidal, P.N.; Ghersevich, M.C.; Arias, E.A.S.; Bosetti, F.; Blatter, M.F.C.; Miceli, D.D.; Castillo, V.A. Adrenal cortex stimulation with hCG in spayed female dogs with Cushing’s syndrome: Is the LH-dependent variant possible? Open Vet J 2021, 11, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutzler, M.A. Possible relationship between long-term adverse health effects of gonad-removing surgical sterilization and luteinizing hormone in dogs. Animals 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meij, B.P.; Kooistra, H.S.; Rijnberk, A. Hypothalamus-Pituitary System. In Clinical Endocrinology of Dogs and Cats an Illustrated Text, 2nd ed.; Rijnberk, A.; Kooistra, H.S., Eds.; Schlütersche, Hannover, Germany, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 25-34.

- Fracassi, F.; Gandini, G.; Diana, A.; Preziosi, R.; van den Ingh, T.S.G.A.M.; Famigli-Bergamini, P.; Kooistra, H.S. Acromegaly due to a somatroph adenoma in a dog. Domest Anim Endocrinol, 2007, 32(1), 43-54. [CrossRef]

- Steele, M.M.E.; Lawson, J.S.; Scudder, C.; Watson, A.H.; Ho, N.T.Z.; Yaffy, D.; Batchelor, D.; Fenn, J. Transsphenoidal hypophysectomy for the treatment of hypersomatotropism secondary to a pituitary somatotroph adenoma in a dog. J Vet Intern Med 2024, 38(1), 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.M.; Diaz-Espineira, M.; Mol, J.A.; Rijnberk, A.; Kooistra, H.S. Primary hypothyroidism in dogs is associated with elevated GH release. J Endocrinol 2001, 168(1), 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Espiñeira, M.M.; Galac, S.; Mol, J.A.; Rijnberk, A.; Kooistra, H.S. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone-induced growth hormone secretion in dogs with primary hypothyroidism. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2008, 34(2), 176–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, T.; Mooney, C.T. Hypothyroidism associated with acromegaly and insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus in a Samoyed. Aust Vet J 2004, 92(11), 437–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasotto, R.; Berlato, D.; Goldschmidt, M.H.; Zappulli, V. Prognostic Significance of Canine Mammary Tumor Histologic Subtypes: An Observational Cohort Study of 229 Cases. Vet Pathol 2017, 54(4), 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkenberg, H.; Sallander, M.H.; Hedhammar, A. Feeding, exercise and weight identified as risk factors in canine diabetes mellitus. J Nutr 2006, 136, 1985–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipperman, B.S.; German, A.J. The responsibility of veterinarians to address companion animal obesity. Animals, 2018, 8, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rak, M.B.; Gilor, C.; Niessen, S.J.M.; Furrow, E. Spontaneous remission and relapse of diabetes mellitus in a male dog. J Vet Intern Med 2024 (Online ahead of print). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).