1. Introduction

Zeolites are lightweight materials because they have a crystalline lattice particularly reach of cavities [

1,

2,

3]. The crystalline lattice of zeolites consists of a three-dimensional aluminosilicate network, composed of SiO

4 and AlO

4 tetrahedra connected together by the oxygen atoms [

4]. Since negative charges are present in the aluminosilicate framework, extra-framework cations are required for the electroneutrality condition. Monovalent metal cations are located close to the aluminum atoms in order to balance their negative charges, while bivalent metal cations are positioned halfway between two neighbors negatively charged sites. In particular the extra-framework ions, typically present in the nature-made zeolites, are alkali (K

+, Na

+) and alkaline-earth (Ca

2+, Mg

2+) metal cations. Since mineral zeolites have mostly aluminous nature, i.e., they are characterized by a low value of the Si/Al ratio, which usually ranges from 4 to 7 [

5], a large amount of charge balancing metal cations is contained. Many natural zeolites contain iron, that causes a reddish coloration in the mineral. Iron can be present both in the covalent framework (isomorph substitution of silicon, like in the aluminum case) and/or in the extra-framework, as charge balancing cations (ferric cations, Fe

3+) [

6].

Zeolites are microporous crystalline materials due to the presence of large and small reticular cavities (α and β cages, respectively). These cages are connected each other to form regular arrays of channels. Extra-framework cations and adsorbed water molecules are located inside these channels close to the aluminum atoms. Owing to the strong electrostatics interaction (Coulomb’s forces) between the extra-framework cations and the negatively charged aluminum atoms, such cations cannot move under the effect of an electric field at room temperature. Actually, the negative charge is not completely localized on the aluminum atoms, but it resonates in a ‘nucleophilic area’, including the aluminum atom and the four neighbor oxygen atoms [

7]. Differently, at high temperature, cations with single electric charge (i.e., K

+ or Na

+) have enough kinetic energy for hopping among empty neighbor nucleophilic areas [

8]. Empty nucleophilic areas are present in the zeolite framework because of the contained bivalent cations, whose presence leaves some unbalanced negative sites in the framework. Electrical transport in the dehydrated zeolites has been investigated by different authors [

9,

10]. They have formulated a conduction model based on the presence of a ‘free ionic conduction zone’ in the crystalline lattice [

11,

12,

13], that consists of free cationic conduction bands located just in the middle of the largest channels (that is those containing the super-cages). According to this model, zeolites have negative temperature coefficient behavior, indeed their resistivity decreases with the increasing of the temperature [

14,

15]. This phenomenon can be advantageously exploited for several technological applications, like for examples the fabrication of new thermistors [

16], thermal switches, temperature sensors, and other temperature-related devices. Clinoptilolite is one of the most common types of natural zeolite [

17,

18], widely available on the market at a very low cost. In addition, clinoptilolite has very good thermal stability and mechanical proprieties due to the high compact organization of lamellar crystals in the inner structure [

19]. These characteristics allow to use clinoptilolite for fabricating very resistant functional devices.

Here, the negative temperature coefficient properties of a natural clinoptilolite sample have been investigated. The sample has been first morphologically and chemically characterized, in order to establish its exact nature. In particular, the sample morphology has been investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) has been used to determine the mineral chemical composition and to investigate the thermal stability. XPS tests have been performed on the powdered sample for achieving optimal results. The clinoptilolite specific surface area and the pore size have been also accurately measured by using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis, since the electrical transport mechanism takes place just in the microporosity.

2. Materials and Methods

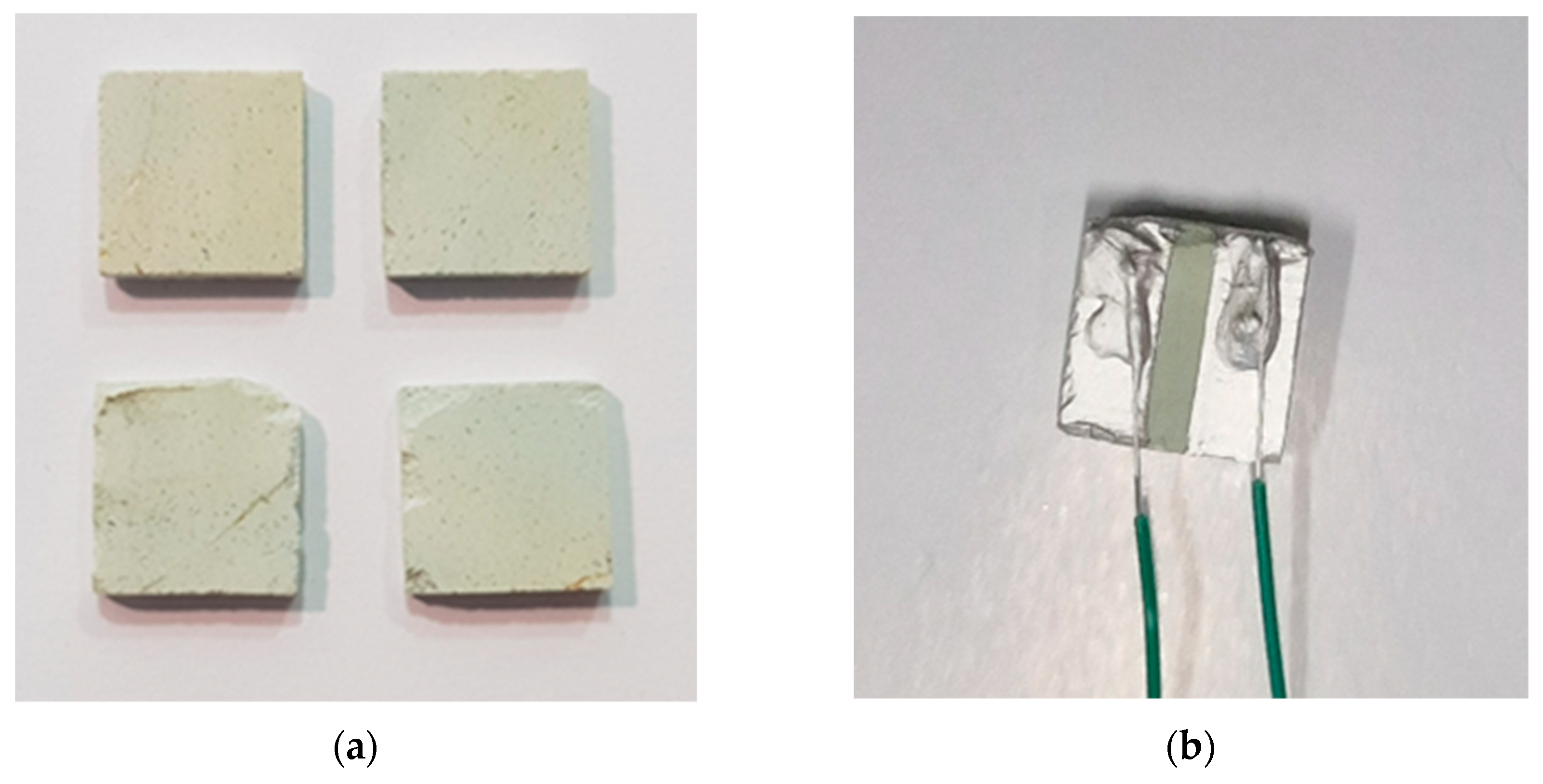

The clinoptilolite mineral was supplied by T.I.P. (Technische Industrie Produkte, GmbH, Waibstadt, Germany). The natural zeolite stone has been mechanically shaped in order to obtain squared monoliths with a thickness of only a few millimeters (see

Figure 1a). The squared monoliths have been obtained by using a 3-axis computer numerical control (CNC) vertical milling machine (Super proLIGHT 1000, Vertical Machining Center). The irregularly shaped stone has been blocked in a press and successively cut by using a mini metal hacksaw. Then the sample glued on a wooden support has been successively clamped in the milling machine vice and machined. The processing cycle included an initial roughing stage to obtain samples with a programmed thickness of ca. 4 mm, subsequently reduced to 2.5 mm. In the second stage the square-shaped samples of 10 mm have been produced, and excess of surface material has been removed up to reach the desired thickness. The electrodes for characterizing the NTC behavior have been prepared by using a ceramic conductive paste (XeredEx, XD-120, SGS) and a copper wire with a diameter of 0.6 mm was used for the electrical connections (see

Figure 1b).

The morphological characterizations have been performed by using a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM, Quanta 200 FEG microscope, FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA). The surface of the mineral has been polished, chemically etched and observed at very high magnification by SEM, in order to investigate the nano-sized clinoptilolite texture, made of lamellas with an identical thickness of 40nm. In particular, the sample was first grained and then polished by silicon carbide paper with a grit size of 4,000 (P4000, Microcut Silicon Carbide grinding paper, U.S.A, Buehler). Owing to the larger number of Si atoms contained in clinoptilolite compared to the Al atoms (5.4:1 for our zeolite sample), chemical etching was based on the desilication reaction (dissolution of the silica framework with formation of soluble sodium silicate). In particular, a sodium hydroxide (NaOH) aqueous solution (2.65M) was used for the clinoptilolite mineral etching and a treatment time of 3h at room temperature was used. It must be pointed out an etching treatment based on the dealumination reaction cannot be effective since it causes only the formation of lattice defects.

The mineral’s surface chemical composition has been studied by means of X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) on samples of clinoptilolite in the ‘as received’ and powdered form. XPS measurements have been carried out in an ultra-high-vacuum (UHV) chamber equipped with a non-monochromatized X-ray source (Mg Kα photon at 1253.6 eV) and a VSW HA100 hemispherical analyzer (with PSP electronic power supply and control), leading to a total energy resolution of 0.86 eV. The binding energy (BE) scale of XPS spectra was calibrated using the Au 4f peak at 84.0 eV as a reference. Quantitative analysis has been performed on core levels by Voigt line-shape deconvolution after background subtraction of a Shirley function (the atomic percentages are determined with an error of ±0.25 %). The zeolite in powdered form is the preferential choice for surface analysis, due to low outgas in UHV; however, several annealing at temperatures up to 150°C were necessary on the natural bulk stone, to check its thermal stability, in order to obtain the same results, like in the powder case.

Nitrogen adsorption analysis was performed on clinoptilolite by means of a 3Flex adsorption analyzer (Micromeritics, Norcross). N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms were recorded at 77 K and SSA was determined by nitrogen from the linear part of the Brunauner−Emmett−Teller (BET) equation. The pore volume of clinoptilolite was calculated from the N2 adsorption isotherm at a 0.85 p/p0. Nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT) was applied to the N2 adsorption isotherm to evaluate the micro/mesopore size distributions. Before the analysis, the sample was degassed at 120 °C under vacuum (P < 10−7 mbar). The adsorption measurements were performed by using high-purity gases (>99.999%).

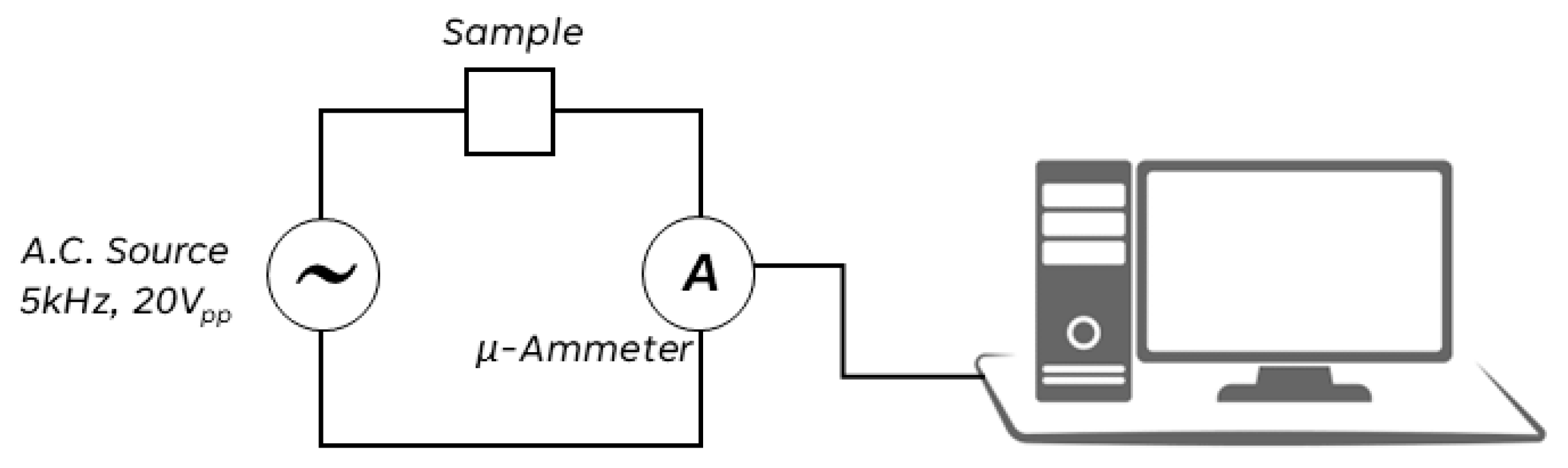

Electrical transport in high impedance ionic conductors (MΩ magnitude order) can be easily investigated. Indeed, a sinusoidal voltage, produced by a function generator, can be applied to this high impedance conductor without the risk of overloading the equipment, since the resulting electrical current has very low intensity (µA magnitude order) for the high impedance value. Owing to the very high signal stability, a direct digital synthesis (DDS) function generator is the most adequate sigmoidal voltage source. The intensity of such microcurrent can be measured (effective value, RMQ) by using a large bandwidth A.C. microammeter of a digital multimeter (DMM). The bandwidth should be high enough for allowing the use of voltage signals with frequency higher than 1kHz, as re-quired to avoid the electrode polarization phenomena. Such device may also include a datalogger system, that allows to record the current intensity measurements. Zeolites are ionic conductors with single charge-carrier, characterized by a very high impedance value; this physical characteristic allows to study these materials by such a simple approach. Two electrodes were placed on the surface of the square-shaped clinoptilolite monolith, in order to test the electric behavior under a fast uncontrolled heating; successively, the system was put in contact with the light bulb surface. The electric current intensity was measured by a true-RMS digital multimeter (DMM) placed in series with a sinusoidal signal generator (see

Figure 2). The square-shaped clinoptilolite sample was connected to an A.C. voltage source (sinusoidal voltage signal of 20V

pp, 5kHz) and the current intensity flowing in it was measured by connecting a wide-band true-RMS digital multimeter (DMM), set as A.C. microammeter, in series with the sample. Electric signals were measured and recorded during the time by using the devoted DMM datalogger software.

A direct digital synthesis (DDS) function generator (Gratten, ATF20B+) was used as voltage source and a true-RMS, 10kHz bandwidth, DMM (Uni-Trend, UT61E) was used as an A.C. microammeter. The effective current intensity value (Ieff) was recorded on a PC connected with a devoted datalogging software. A fast specimen heating was achieved by placing its bottom surface in contact with the glass bulb surface of a high-power halogen lamp (NT U H4, 12V, 60/55W, P43T), powered up by a D.C. power supply (Velleman, LABPS 3005D, 30V/5A). The clinoptilolite sample was prepared with a reduced thickness in order to facilitate heat transfer from the heat source (i.e. the bulb) to the sample, and in addition, a silver conductive paste was placed between the sample and the light bulb. Successively, the following test was performed: the sample was heated slowly and in a calibrated manner by using an aluminum block containing a ceramic heating cartridge. The sample was thermally insulated by a layer of Kapton/cotton wadding; for this purpose, the heating block set of a 3D printer was used. A digital datalogger thermometer (Uni-Trend, UT-325) was used to measure and record the temperature over time.

3. Results

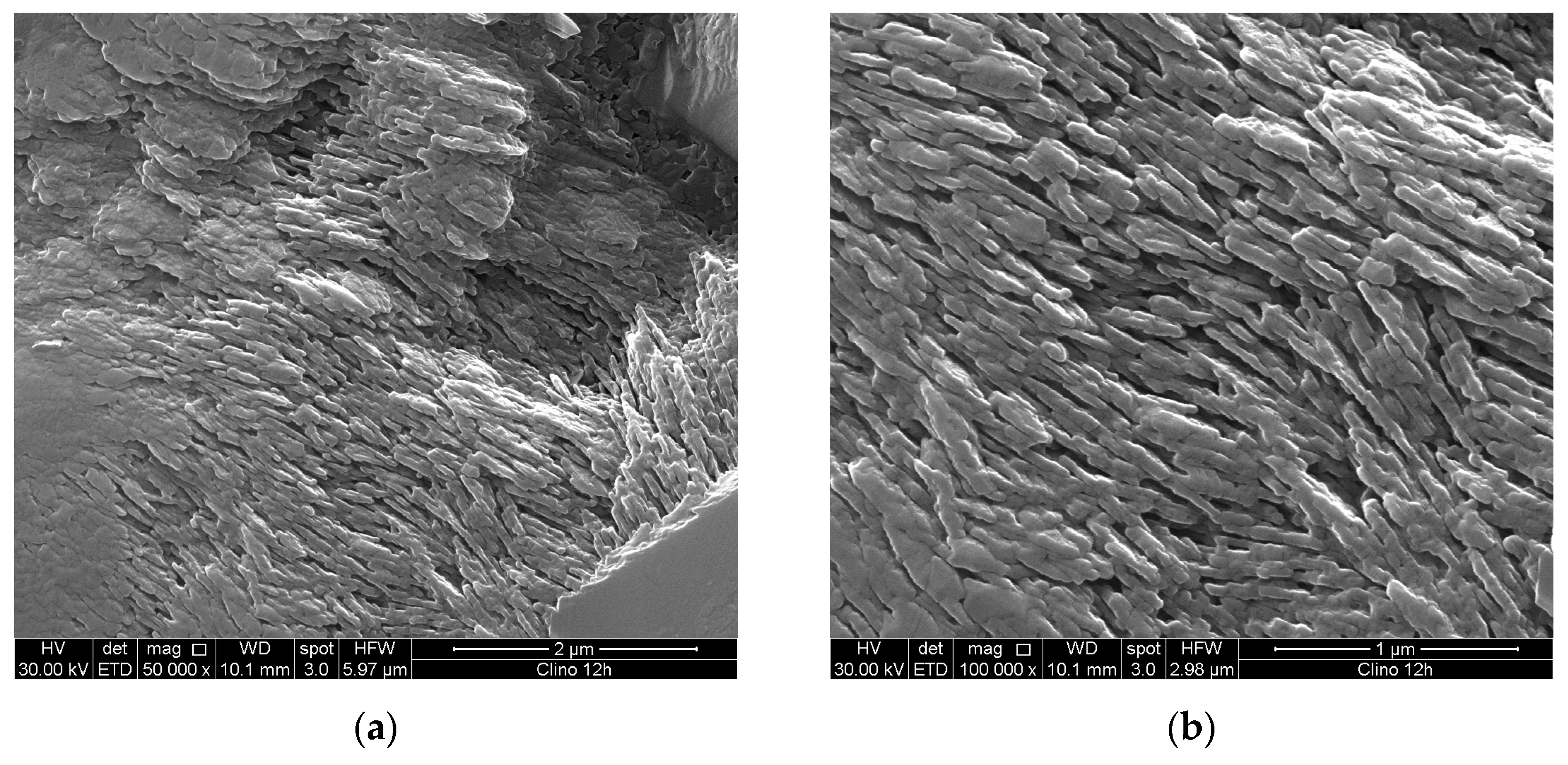

The SEM micrographs of the etched clinoptilolite sample surface (see

Figure 3a,b) clearly show that the mineral is made of tendentially isoriented stacks of lamellar crystals. All lamellas have the same thickness (40nm), while the other two sizes are of a few hundred microns. Such morphology is a characteristic of the clinoptilolite [

10,

20]; however, many other nature-made materials show a similar microstructure [

21]. The good mechanical performance can be ascribed just to this special morphology. Owing to the high clinoptilolite content, the electrically conductive zeolite lamellar crystals are interconnected and form percolation networks, with paths crossing the full solid structure.

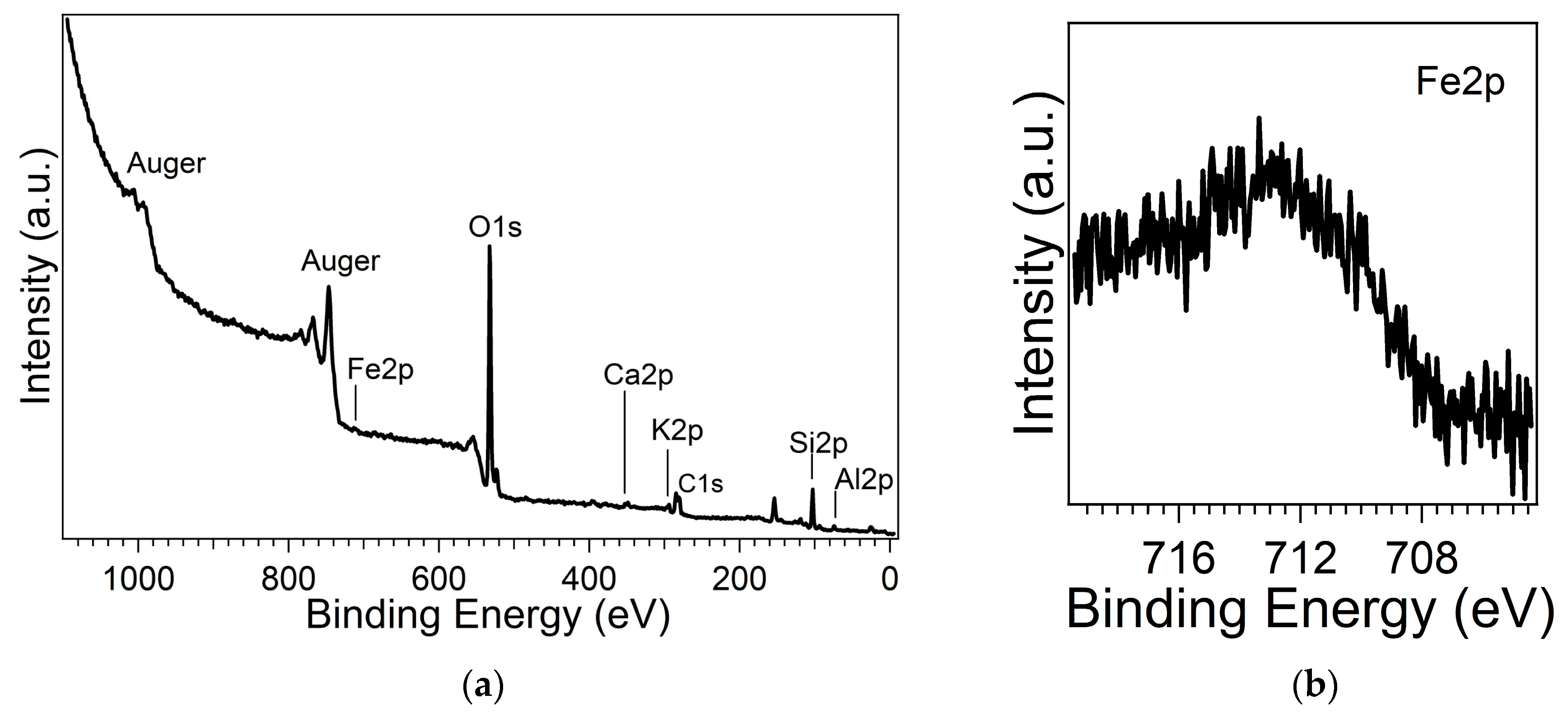

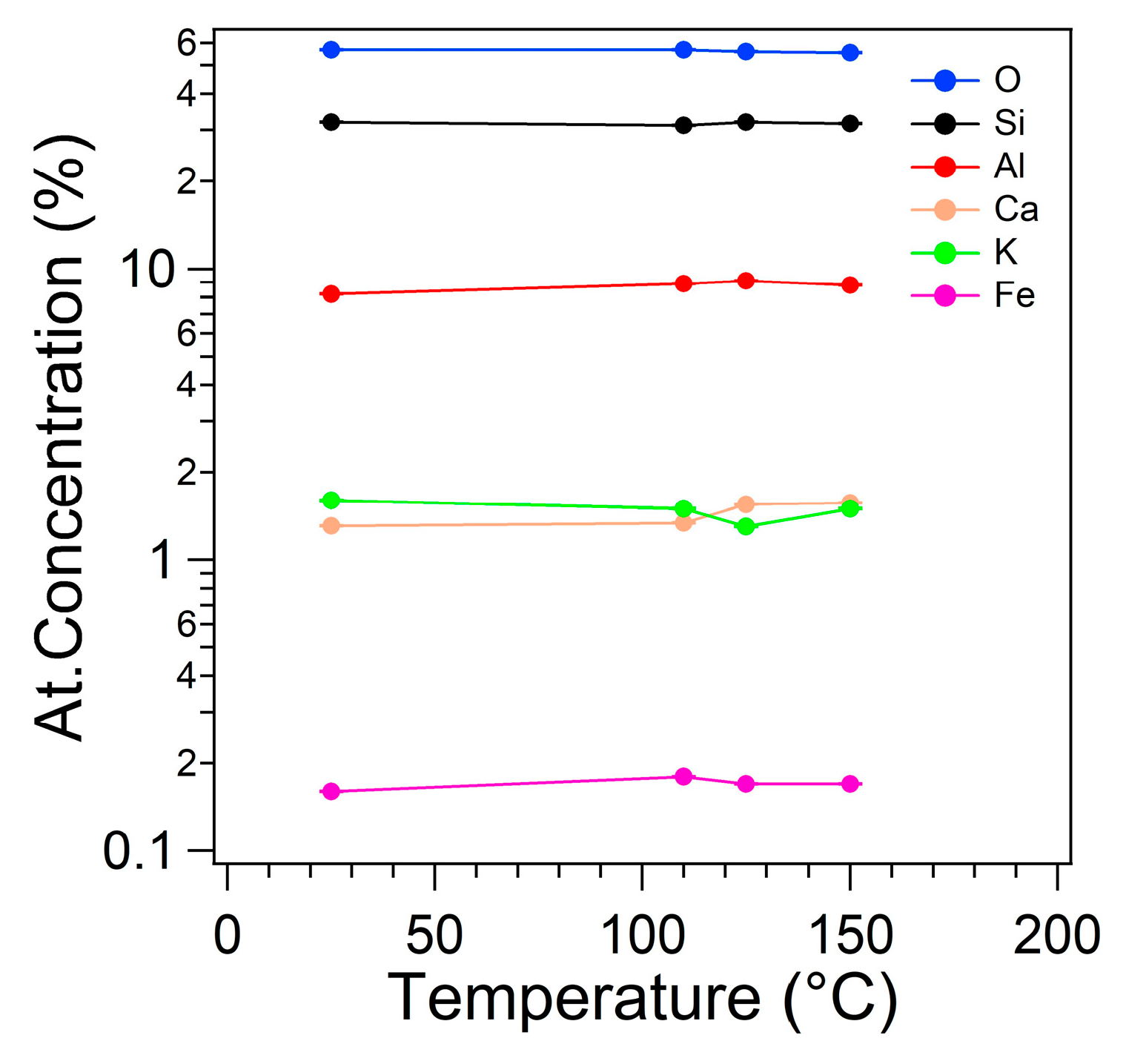

The chemical composition obtained by XPS analysis (

Figure 4a) revealed the presence of Si (Si2p), Al(Al2p), O(O1s) as framework elements, and Ca (Ca2p), K (K2p) as ex-tra-framework elements. Fe (Fe2p) has also been identified (

Figure 4b); it shows a broad and complex core level lineshape, suggesting the presence of iron in different chemical configurations, likely Fe both in framework and extra-framework positions.

It is observed a BE shift of all core levels due to charging phenomena of about 5.6 eV (taking into account the energy reference from adventitious carbon at 285 eV). Al2p and Si2p BE positions are 74.5 eV and 102.9 eV (main), respectively, in agreement with the literature [

22,

23].

Table 1 reports the chemical composition in surface atomic percentages. K and Ca elements are the most abundant types of charge compensating cations and there-fore the mineral sample can be classified as clinoptilolite-K,Ca.

Chemical composition vs. temperature is shown in

Figure 5. As visible, the chemical composition is substantially constant with the increasing of the temperature up to 150°C. Therefore, the clinoptilolite sample does not modify its structure in the temperature range involved in the electrical measurements.

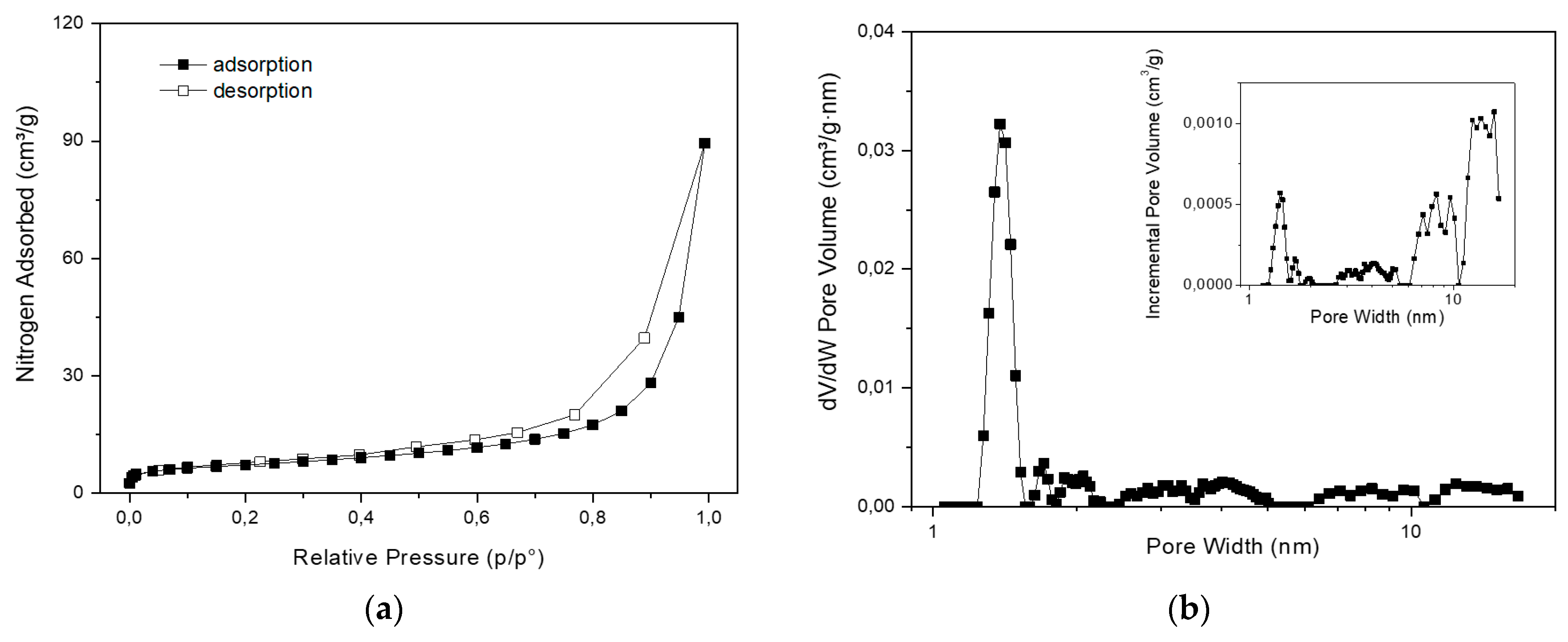

Nitrogen adsorption/desorption analysis showed that clinoptilolite powder has a BET specific surface area of 25 ± 0.1 m²/g and a total pore volume of 0.032 cm³/g. NLDFT pore distribution analysis shows microporous and mesoporous fractions: a significant portion of porosity (about 16%) is narrowly centered at 1.4 nm, being compatible with zeolite crystalline microporosity; the remaining (meso)porosity extends mainly from 3 nm to 20 nm and it is ascribable to interlamellar space. These results are in line with several specimen of natural clinoptilolite of different origins that have not undergone acid or high-temperature calcination treatments [

24,

25,

26,

27].

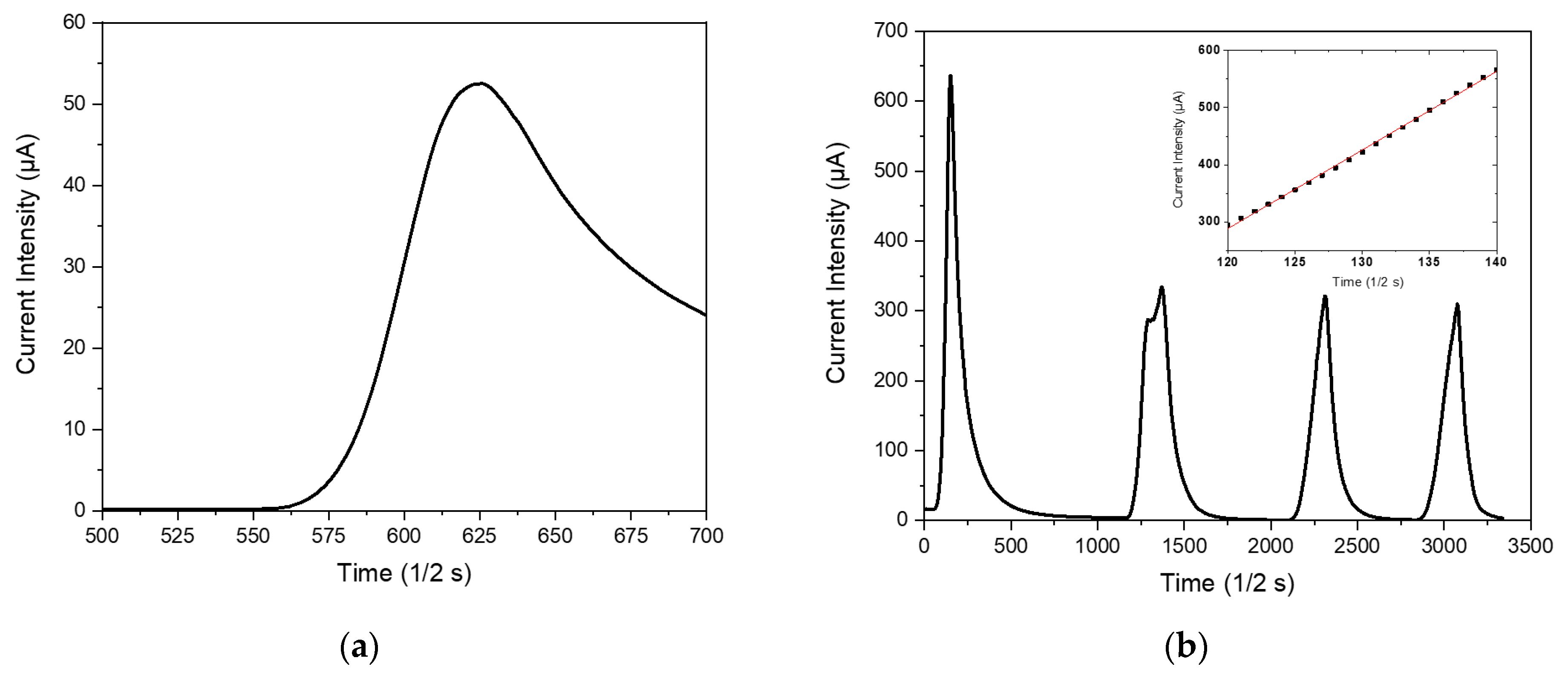

The effect of a fast increase of temperature on the mobility of the extra-framework cations (actually, K+ is the only involved charge carrier) has been investigated by monitoring, under a constant sinusoidal voltage, the variation of the effective current intensity flowing in the sample, during a rapid heating process.

As visible in

Figure 7a, the application of a thermal pulse to the clinoptilolite monolith promptly generates an electrical micro-current in the ceramic sample. Such micro-current grew up with the turning on of the lamp. During the successive cooling step in air (i.e., the turning off of the incandescent lamp), the micro-current intensity readily de-creased until to reach the starting negligible value. The resulting peak in the current intensity had a slightly asymmetric profile since the process of sample cooling in air resulted slower than the previous heating process. In particular, the heating step followed a linear trend (see inset in

Figure 7b) with a rate of (13.8±0.1) µA/s, while the cooling step followed a parabolic law.

Figure 7b shows the sample behavior under repeated heating/cooling cycles; as visible, four re-peated cycles were unable to modify the electric behavior of such NTC materials.

Since during the experiments the sinusoidal generator provides a constant voltage value of 20V

pp, the sample impedance can be calculated by using the measured current intensity values. The temporal evolution of the calculated sample impedance is shown in

Figure 8a. As visible, the heating process produces a significant decrease in the sample impedance value, that can be conveniently represented by using the logarithmic scale; in-deed, the impedance value changes of 2-3 magnitude orders during the heating/cooling process. In particular, like for the current intensity, the impedance value varies quite linearly during the heating stage, while it decreases non-linearly (hyperbolically) during the cooling back at room temperature. According to the slope of the linear temporal behavior of impedance, this quantity changes very quickly with time increase and the switching process results fully reversible. However, as visible in

Figure 8b, some hysteresis is observed during repeated heating/cooling cycles.

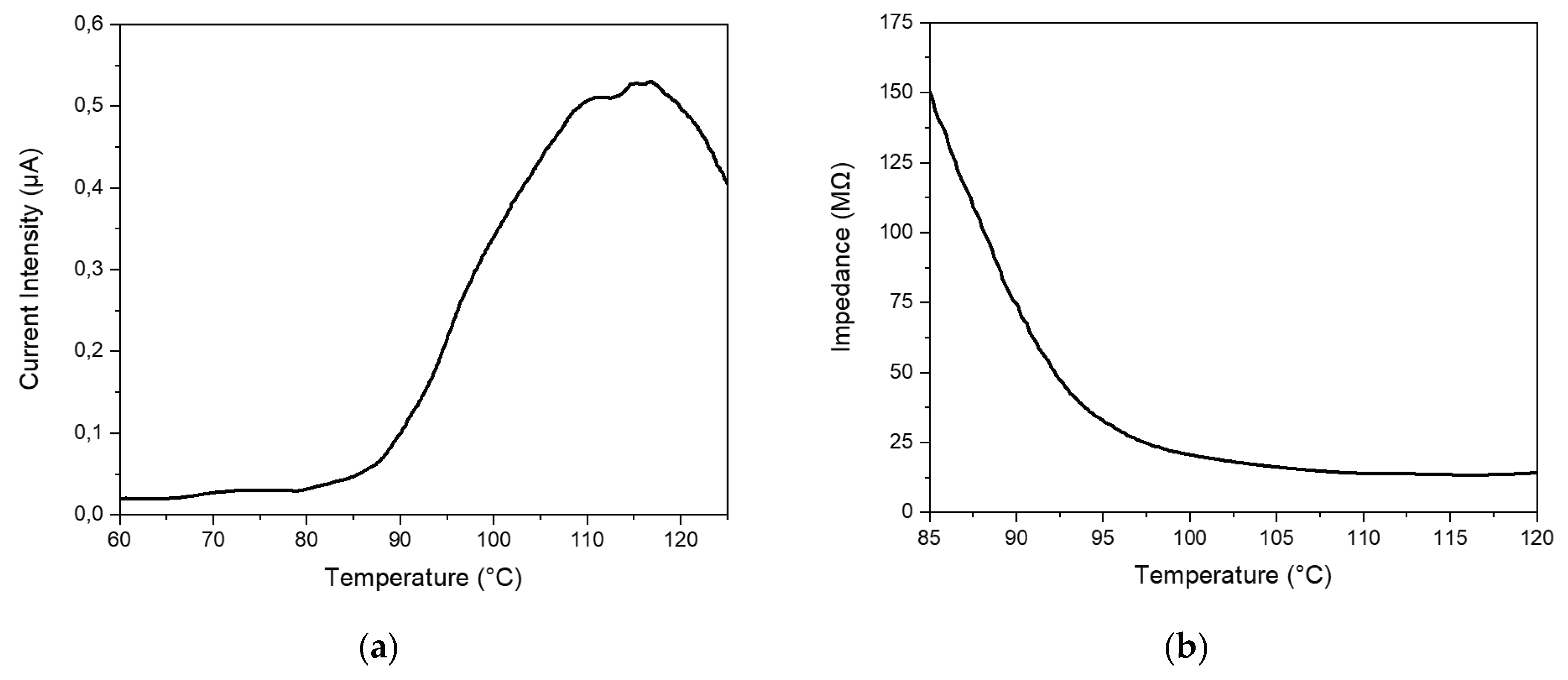

Heating tests at known temperature values were similarly performed by using time-resolved effective current intensity measurements (see

Figure 9). Both current intensity and calculated impedance curves are given; however, in this case, also temperature was measured during the time. As visible in

Figure 9a slow/controlled heating process was capable to give a quite asymmetric I

eff-T peak, just like in the case of a thermal pulse.

4. Discussion

Zeolites are low-density crystalline aluminosilicates. They have a covalent crystalline structure with extra-framework positive charges (charge balancing cations). Vučelić de-fined this particular structure as a ‘reverse’ metal lattice [

11]. According to the electrical conduction model of Vučelić [

12,

13], only those extra-framework charges moving in a ‘free ionic conduction zone’ (i.e., the free cationic conduction band located in the middle of channels) can promote electrical conduction. Indeed, ions at the centers of cavities are carrier of current and move through the zeolite with a low activation energy. The Vučelić model is analogous to the behavior of electrons in a fixed cation electromagnetic field (i.e., the metallic crystal structure) and to their conduction through the conduction zones.

The electrical properties of zeolites are mainly depending on the contained monovalent metal ions because they are less strongly held by the negatively charged lattice and can easily migrate between two neighboring negative sites. In more detail, the clinoptilolite electrical conductivity, σ(T), depends only on the following three factors: (i) charge of the electrical carriers: Z∙e

-, where e

- is the elementary charge (e

- =1.602∙10-19 C), (ii) concentration of the electrical carriers: [MeZ

+], and (iii) mobility of the electrical carriers: μ, according to the following physical law: σ(T)= Σ

i[Z

i∙e

-∙[Me

z+]

i∙μ

i], where the summatory is formally extended to all extra-framework cations present in the substance. However, since the tested sample is clinoptilolite-K,Ca, potassium ions located in the super-cages are principally involved in the migration under the applied sinusoidal field (5kHz, 20V

pp). Indeed, the contribution of Ca

2+ cations is negligible because they have a larger electrical charge and are present in the clinoptilolite sample at concentrations lower than K

+. Iron atoms do not participate to the electrical transport mechanism because some of them are located in the framework (isomorphous substitution), just like the aluminum atoms, and the others have a large electrical charge. Finally, it is possible to approximately write:

where [K

+] * is the concentration of excited K

+ cations. Each K

+ ions is located in a potential well, whose walls are represented by the four negatively-charged oxygen atoms of the nucleophilic site [

10], and the concentration of excited K

+ present at zeolite cage center is temperature-dependent, indeed it increases with raising up of temperature, thus determining an increase in the material electrical conductivity.

5. Conclusions

Clinoptilolite is an electrically conductive material (single charge-carrier ionic conductor), that has shown a strict dependence of its impedance value on temperature. In particular, impedance changes promptly and linearly with the heating in the temperature range of 25 – 120°C. Such a physical characteristic allows to propose this material has an alternative to the traditionally available NTC semiconductors. According to the SEM investigation, the sample is made of single lamellar crystals closely compacted together. Such a microstructure allows both good mechanical properties and the presence of percolative paths in the sample, which is essential for the electrical conduction properties. Since the electrical transport takes place on the clinoptilolite surface, the specific surface area and porosity have been measured by BET analysis. In particular, it has been found that the sample is characterized also by the surface area of 25 ± 0.1 m²/g and pores with an average size ranging from 1.4 to 20 nm. The clinoptilolite sample has been accurately characterized by XPS analysis, in order to establish the exact framework composition (Si/Al = 4.6) and the types/quantity of extra-framework cations. According to this analysis the monovalent K+ cation is the only available charge-carrier for the electrical transport. In addition, XPS analysis has provided information on the contained iron cations, that is present both in the framework and extra-framework regions and the thermal stability of samples.

Supplementary Materials

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C.; methodology, G.C.; validation, G.C., L.S., L.A., R.V., R.C., G.G.; formal analysis, G.C., L.S., L.A., R.V., R.C., G.G.; investigation, G.C., L.S., L.A., R.V., R.C., G.G.; resources, G.C. and L.S.; data curation, G.C., L.S., L.A., R.V., R.C., G.G..; writing—original draft preparation, G.C., L.S., L.A., R.V., R.C., G.G.; writing—review and editing, G.C., L.S., L.A., R.V., R.C., G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external founding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Maria Cristina Del Barone of LAMEST laboratory (IPCB-CNR) for SEM analysis, to Docimo Fabio of (IPCB-CNR) for his technical support in the square monolith realization and useful discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- P. Misaelides. Application of natural zeolites in environmental remediation: A short review. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2011, 144, 15–18. [CrossRef]

- Jha, B.; Singh, D. N. Basics of Zeolites. In: Fly Ash Zeolite: Innovations, Applications, and Directions. Part of the book series: Advanced Structured Materials; Springer Verlag, Singapore, 2016, 78, 5 –13. [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, S. M.; Carrado, K. A.; Dutta, P. K. Handbook of Zeolite Science and Technology. 1st Ed.; Boca Raton; CRC Press; 2003; p. 1204. [CrossRef]

- Koohsaryan, E.; Anbia, M. Nanosized and Hierarchical Zeolites: A Short Review. Chinese J. Catal. 2016, 4, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Leng, S.; Guo, H.; Yu, J.; Li, W.; Cao, L.; Huang, J. Quantitative Arrangement of Si/Al Ratio of Natural Zeolite Using Acid Treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 498, 143874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, R.; Nagy, J. B.; Giordano, G.; Katovic, A.; Testa, F. Isomorphous Substitution in Zeolites. C. R. Chim. 2005, 8, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunova, E. L.; Mikosch, H. Cation Site Preference in Zeolite Clinoptilolite: A Density Functional Study. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 177, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohgushi, T.; Ishimaru, K.; Adachi, Y. Movements and Hydration of Potassium Ion in K-a Zeolite. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009, 113, 2468–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäf, O.; Ghobarkar, H.; Adolf, F.; Knauth, P. Influence of Ions and Molecules on Single Crystal Zeolite Conductivity under in Situ Conditions. Solid State Ion. 2001, 143, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, G.; Schön, G. Ionic Conductivity in Dehydrated Zeolites. J Mater. Sci. 1992, 27, 6036–6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuc̆elić, D., Juranič, N.; Macura, S.; Šušič, M. (1975). Electrical conductivity of dehydrated zeolites. J. Inorg, Nucl. Chem. 1975, 37, 1277-1281.

- Vuc̆elić, D. Ionic Conduction Bands at Zeolite Interfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 1977, 66, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučelić, D.; Juranić, N. The effect of sorption on the ionic conductivity of zeolites. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 1976, 38, 2091–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, K. E., Etu, I. A., Nwangwu, E. O., & Osuagwu, E. U. A simple thermistor design for industrial temperature measurement. IOSR J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2016, 11, 57 – 66. [CrossRef]

- Becker, J. A.; Green, C. B.; Pearson, G. L. Properties and Uses of Thermistors—Thermally Sensitive Resistors. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1947, 26, 170–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, R. K.; Naik, G. M. Thermistors - In Search of New Applications, Manufacturers Cultivate Advanced NTC Techniques. Sens. Rev. 2002, 22, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M. Á.; Hernández, G. I.; Portillo, R. I.; Velasco, M. de los Á.; Santamaría-Juárez, J. D.; Rubio, E.; Petranovskii, V. Influence of Chemical Pretreatment on the Adsorption of N2 and O2 in Ca-Clinoptilolite. Sep. 2023, 10 (2), 130. [CrossRef]

- Mastinu, A.; Kumar, A.; Maccarinelli, G.; Bonini, S. A.; Premoli, M.; Aria, F.; Gianoncelli, A.; Memo, M. Zeolite Clinoptilolite: Therapeutic Virtues of an Ancient Mineral. Mol. 2019, 24, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, P.; Sprynskyy, M.; Terzyk, A. P.; Lebedynets, M.; Namieśnik, J.; Buszewski, B. Porous Structure of Natural and Modified Clinoptilolites. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 297, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavo L., Cammarano A., Carotenuto G., Longo A., Palomba M., Nicolais L., An overview of the advanced nanomaterials science. Inorganica Chim. Acta. 2024, 559, 121802. [CrossRef]

- Jiao D., Liu Z.Q., Qu R.T., Zhang Z.F. Anisotropic mechanical behaviors and their structural dependences of crossed-lamellar structure in a bivalve shell. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 59, 828–837. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grüenert, W.; Muhler, M.; Schröder, K. P.; Sauer, J.; Schlögl, R. Investigations of Zeolites by Photoelectron and Ion Scattering Spectroscopy. 2. A New Interpretation of XPS Binding Energy Shifts in Zeolites. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 10920–10929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavo L., Boccia V., Aversa L., Verucchi R., Carotenuto G., Valente T. Natural Clinoptilolite Nanoplatelets Production by a Friction-Based Technology. Mater. Proc. 2023, Proceedings of IOCN 2023, MDPI, Conference Online, 5–19 May 2023. 5–19 May. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Basabe, Y., Rodriguez-Iznaga, I., de Menorval, L. C., Llewellyn, P., Maurin, G., Lewis, D. W., Binions R., Autie M.,Ruiz-Salvador, A. R. Step-wise dealumination of natural clinoptilolite: Structural and physicochemical characterization. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 135(1-3), 187–196. [CrossRef]

- Favvas E.P., Tsanaktsidis C.G., Sapalidis A.A., Tzilantonis G.T., Papageorgiou S.K., Mitropoulos A.C., Clinoptilolite, a natural zeolite material: Structural characterization and performance evaluation on its dehydration properties of hydrocarbon-based fuels. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 225, 385–391. [CrossRef]

- Korkuna O., Leboda R., Skubiszewska-Ziȩba J., Vrublevs’ka T., Gun’ko V.M., Ryczkowski J. Structural and physicochemical properties of natural zeolites: Clinoptilolite and mordenite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 87, 243–254. [CrossRef]

- Wahono, S.K.; Prasetyo, D.J.; Jatmiko, T.H.; Suwanto, A.; Pratiwi, D.; Hernawan; Vasilev, K. Transformation of Mordenite-Clinoptilolite Natural Zeolite at Different Calcination Temperatures. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Tangerang, Indonesia, 1–2 November 2018; Volume 251, p. 012009. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).