1. Introduction

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) a global pandemic in December 2019 in Wuhan, China [

1,

2]. This declaration impacted public health, with figures of more than 649 million confirmed cases and more than 6.6 million deaths globally by December 2022 [

3]. Data indicate that certain groups, such as older people and those with pre-existing medical conditions, were at higher risk of developing severe forms of the disease.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a massive reorganization of health services worldwide [

4]. This restructuring, while necessary to address the health crisis, generated difficulties and serious consequences globally. The suspension of routine hospital care, the transformation of services to care for the infected, and containment measures had a significant impact, affecting not only patients with COVID-19, but also those with other medical conditions. One of the groups where the impact of pandemic effects has been demonstrated is people with lung cancer [

5].

Malignant neoplasm occupies a position of great relevance at the global health level due to its high incidence and mortality rate. This group, due to its primarily respiratory nature, age and compromised immune system [

6,

7,

8], has emerged as a group particularly vulnerable to contracting COVID-19 and experiencing significant complications [

8,

9]. On the other hand, integrated health management during the pandemic has comprehensively affected both those already diagnosed with lung cancer [

10,

11] and new diagnoses.

On the one hand, the population with diagnosed lung cancer has faced setbacks and changes in their treatment [

12], which has negatively affected their symptom management and quality of life. Redeployment of staff and shortages of medical resources have directly impacted the care of lung cancer patients. A cross-sectional study of 356 cancer centres worldwide found that 88% of cancer centres faced difficulties in providing care, due to the burden on the healthcare system, lack of protective equipment, reduced staffing and limited access to drugs [

13].

On the other hand, it has had a significant impact on the incidence of new diagnoses, leading to substantial problems in early detection and comprehensive patient management [

14]. A decrease in diagnoses has been observed, possibly attributed to a reduction in screening tests and medical visits [

15]. In addition, diagnoses tend to be made at later stages due to delays in medical care and barriers to access [

16]. This scenario raises concerns about the effectiveness of interventions and patient prognosis. In addition, the risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 while seeking care for lung cancer diagnosis and treatment represents another challenge [

17]. Recommendations for lung nodule detection and assessment have changed during the pandemic, highlighting the need for reallocation of resources and additional considerations for exposure to COVID-19 [

4]. An expert group has proposed specific guidelines, such as deferral of initial and annual lung cancer screening, as well as differentiated management according to the size and likelihood of malignancy of detected nodules [

2]. These measures aim to mitigate the risks associated with the pandemic and ensure the safety of lung cancer patients [

18], however, they add to a worsening prognosis that grows as diagnosis or treatment is delayed. On the other hand, a handicap is added to the diagnosis of cancer due to the similarity of symptoms between COVID-19 and cancer [

1,

2].

The aim of this study was to retrospectively analyses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis, mortality rates and survival period of malignant neoplasm of the bronchus and lung in the region of Burgos. This study will support strategies to improve the management of cancer care during health crises, thus contributing to the optimization of public health [

17].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Prospective, longitudinal, single-centre study, carried out in the town of Burgos during 2019, 2020 and 2021, with the aim of analysing the incidence of malignant neoplasms of the bronchus and lung, as well as the characteristics of the disease and the mortality and survival rates.

2.2. Participants

The sample consisted of all patients diagnosed with malignant lung and bronchial neoplasia by the Pneumology unit of the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Burgos, Spain, during the year immediately prior to 31 March 2020, the date on which the pandemic was officially declared, and during the year immediately after that date. This two-stage sampling approach allowed us to capture the variability in incidence between the two periods.

Inclusion criteria for the study included patients diagnosed by histological or clinicoradiological methods.

Patients participated voluntarily, providing the necessary information for the collection of demographic data. Ethical and privacy principles were respected, and all participants gave informed consent for their inclusion in this study. The study adhered to ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the University of Burgos with reference IO-06/2024.

2.3. Procedure

Data collection was carried out systematically, using a template specifically designed for this study. In this way, all relevant patient data were collected, ensuring a homogeneous collection of data, and guaranteeing the consistency of the information collected. The template included the following information:

Gender: Each patient was classified as male or female.

Age: Ages were categorized into age ranges or intervals, to which patients were assigned. The age groups were defined as follows: <30 years, 30-39 years, 40- 49 years, 50-59 years, 60-69 years, 70-79 years, 80-89 years or ≥90 years.

Disease stage: the stage of the disease was recorded for each patient at the time of diagnosis, using the classification of stage I, II, III or IV.

Death: patients who died as a result of the disease were followed up during the three years mentioned above, and the date of those who died as a result of the disease was recorded.

Survival time: For deceased patients, the number of days of survival from the date of diagnosis to the date of death was calculated.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 28 statistical software (IBM-Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Descriptive methods were used, including the presentation of a table with the main clinical and socio-demographic data. Data were presented as number of cases and percentage of the total for categorical variables, and as mean ± standard deviation of the mean for continuous variables.

Although the data for the survival time variable were not normally distributed, it was decided to perform parametric tests on those analyses that included this variable. Some studies have shown empirical evidence of the robustness of the ANOVA test to other non-parametric analyses, even in contexts involving non-normal distributions [

19].

Therefore, to analyses whether there were statistically significant differences in the number of days of survival between the two periods, parametric ANOVA tests were used.

In addition, chi-square tests were also carried out to assess the possible associations between the different categorical variables. To determine whether there were significant differences between expected frequencies and observed frequencies, absolute values greater than 1.96 or -1.96 in the corrected residuals were considered.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample

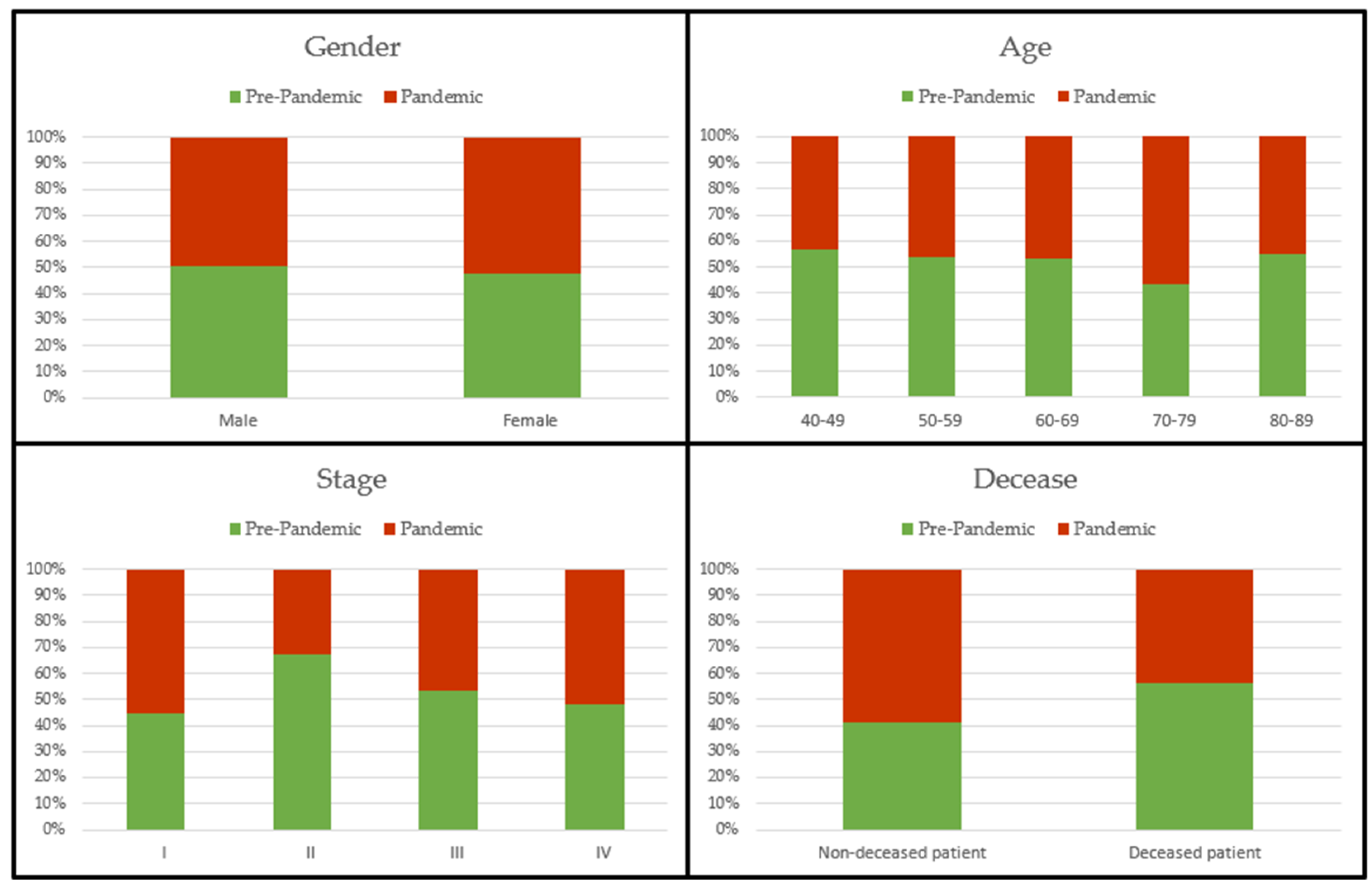

Table 1 and

Figure 1 show the main socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included in the study.

The total study sample consisted of 259 patients, of whom 154 were diagnosed before the pandemic and 105 after the declaration of the pandemic. Of these, 203 (78.4%) were men and 56 (21.6%) were women. As can be seen in

Table 1, males represented a much higher percentage both pre-pandemic and during the pandemic.

The total mean age of the diagnosed patients was 68.77 ± 8.89 years. During these two periods, no cases of malignant neoplasm of the bronchus and lung were diagnosed in persons younger than 40 years or older than 89 years. In both periods the majority of cases were diagnosed in patients aged 60-79 years.

Almost one third (62.9%) of the total cases diagnosed during these periods were already in stage IV, 21.6% in stage III, 6.2% in stage II, and 9.3% still in stage I.

Of the total number of patients diagnosed, 105 (40.5%) were still surviving at the time of the end of follow-up of this study, while 154 (59.5%) died during follow-up. Among all these deceased patients, the mean number of days from diagnosis to death was 229.12 ± 202.36 days.

3.2. Association between Pandemic and Age

Table 2 below shows the inferential results obtained after associating the age groups with the two time periods analysed. As can be seen, the p-value is greater than .05, which means that there were no statistically significant differences between the expected frequencies and the observed frequencies according to the age of the patients.

3.3. Association between Pandemic and Gender

Table 3 below shows the inferential results obtained after associating the gender of the patients with the time periods analysed. As can be seen, the p-value is also greater than .05, which means that there were also no statistically significant differences between the expected frequencies and the observed frequencies according to the age of the patients diagnosed with malignant neoplasm of the bronchus and lung.

3.4. Association between Pandemic and Cancer Stage

Table 4 below shows the inferential results obtained after associating cancer stage with two periods analysed. As can be seen, the p-value is greater than .05, which means that there were also no statistically significant differences between the expected and observed frequencies according to stage.

3.5. Association between Pandemic and Mortality

Table 5 below shows the inferential results obtained after associating mortality with the two time periods analysed. As can be seen, there was a statistically significant association (p=.015) between the two variables. After analysing the corrected residuals, the number of patients who died during the pre-pandemic period was higher than expected, and, on the contrary, it was lower than expected during the pandemic period.

3.6. Association between Pandemic and Years of Survival

Table 6 below shows the differences in survival years between the two years analysed. As can be seen, there were statistically significant differences between the two groups (p=.038). The mean number of days of survival was higher during the pre-pandemic period than during the pandemic.

3.7. Association between Pandemic, Cancer Stage, and Years of Survival

Table 7 below shows the differences in survival years between the two years analysed, considering the different stages of the disease.

As can be seen, there were statistically significant differences between the groups (p=.004). After analysing multiple comparisons between the different groups, statistically significant differences (p<.05) were found between those patients diagnosed with stage I cancer before the pandemic versus the rest of the patients, regardless of their stage of disease and whether they were diagnosed before or after the pandemic. The pre-pandemic stage I diagnosis showed a much longer survival period compared to the others.

In addition, there were also significant differences (p=.026) between those patients diagnosed with stage IV cancer before and after the pandemic. Pre-pandemic stage IV diagnosis showed a longer survival time compared to stage IV diagnosis in the pandemic period.

4. Discussion

Malignant neoplasm of the bronchus and lung is a very significant challenge worldwide, due to its high incidence and mortality rates [

6,

7,

8]. Patients affected by this disease are particularly vulnerable to developing COVID-19 and related complications [

8,

9]. In addition, the pandemic has placed an obvious burden on the healthcare system, and probably also delays in the diagnosis of new cases of lung cancer [

10,

11]. This is an obvious problem, and it is essential to detect the disease in its early stages, as disease progression can lead to a fatal outcome. Furthermore, knowing the diagnosis and stage of the disease is vital to provide the necessary care to manage the symptoms of the disease and to improve the quality of life of affected patients. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on diagnosis, mortality rates and survival time in patients diagnosed with this disease in the region of Burgos.

As in other studies, the results showed a decrease in the number of patients diagnosed during the pandemic period [

14,

15], which could lead to delays in detection as a result of overloading the entire healthcare system, redeployment, and even reduction of various resources. This presents a major problem, as detection of late-stage disease reduces the chances of survival. In this study, most cases were detected at advanced stages, both in the pre-pandemic period and during the pandemic.

Contrary to expectations, there was a higher mortality rate during the pre-pandemic period compared to the pandemic period. It is very likely that these damages do not reflect reality, and are justified by the fact that those patients diagnosed during the pandemic have had a shorter longitudinal follow-up period. It is very likely that the disease has progressed in many of them, and death has occurred after the end of their follow-up in the study.

In terms of survival time, the results showed that patients diagnosed during the pandemic had a shorter survival time from diagnosis to the date of death. Specifically, those patients diagnosed with early stage I cancer before the pandemic had much longer survival times than other patients, regardless of their stage of disease and whether they were diagnosed before or after the pandemic. This indicates that both late detection and detection at the time of the pandemic reduced the survival time of patients.

Moreover, those patients diagnosed with advanced stage IV cancer after the pandemic also showed shorter survival times compared to those diagnosed before the pandemic at the same stage of the disease. This suggests that, although they had little chance of survival at such advanced stages, the COVID-19 health crisis may have caused not only delays in diagnosis, but also difficulties in their management, thus hastening their demise.

The main limitation of this study was the small number of diagnosed patients that made up the sample analysed, as a consequence of it being a single-centre study.

As a future line of research, it is proposed to increase the sample of the study, including data collected in other areas, in order to generalise the results obtained to the whole population.

5. Conclusions

The main results of this study reveal a decrease in cases of malignant neoplasm of the bronchus and lung diagnosed during the COVID-19 pandemic, as a consequence of the overburdening of the health care system during this period. Furthermore, they also show that diagnosis during the pandemic, especially in stages I and IV, considerably reduced the survival time of patients.

Therefore, these data demonstrate the need for further research in this area. This study supports strategies to improve the management of cancer care during health crises, thus contributing to the optimization of public health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G-H.; methodology, G.G-H.; formal analysis, G.G-H.; and Á.G-B.; investigation, G.G-H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N-R.; C.C-R.; and Á.G-B.; writing—review and editing, S.N-R.; C.C-R.; Á.G-B.; M.S-P.; J.J.G-B.; and J.G-S.; visualization, G.G-H.; S.N-R.; C.C-R.; Á.G-B.; M.S-P.; J.J.G-B.; and J.G-S.; supervision, J.J.G-B.; and J.G-S.; project administration, G.G-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Burgos (reference IO-06/2024), for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article are very grateful to all the patients who participated in this longitudinal observational study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Round, T.; Esperance, V.; Bayly, J.; Brain, K.; Dallas, L.; Edwards, J.G.; et al. COVID-19 and the multidisciplinary care of patients with lung cancer: an evidence-based review and commentary. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moubarak, S.; Merheb, D.; Basbous, L.; Chamseddine, N.; Bou Zerdan, M.; Assi, H.I. COVID-19 and lung cancer: update on the latest screening, diagnosis, management and challenges. J. Int. Med. Res. 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojsak, D.; Dębczyński, M.; Kuklińska, B.; Minarowski, Ł.; Kasiukiewicz, A.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 in Patients with Lung Cancer: A Descriptive Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9866646/. 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariniello, D.F.; Aronne, L.; Vitale, M.; Schiattarella, A.; Pagliaro, R.; Komici, K. Current challenges and perspectives in lung cancer care during COVID-19 waves. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2023, 29, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhribah, H.; Zeitouni, M.; Daghistani, R.A.; Almaghraby, H.Q.; Khankan, A.A.; Alkattan, K.M.; et al. Implications of COVID-19 pandemic on lung cancer management: A multidisciplinary perspective. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020, 156, 103120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krist, A.H.; Davidson, K.W.; Mangione, C.M.; Barry, M.J.; Cabana, M.; Caughey, A.B.; et al. Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2021, 325, 962–970. [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher, A.N.; Hammoud, D.A.; Weinberg, J.B.; Agarwal, P.; Mendiratta-Lala, M.; Luker, G.D. Cancer Imaging and Patient Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboueshia, M.; Hussein, M.H.; Attia, A.S.; Swinford, A.; Miller, P.; Omar, M.; et al. Cancer and COVID-19: analysis of patient outcomes. Future Oncology 2021, 17, 3499–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, P.J.; Gould, M.K.; Arenberg, D.A.; Chen, A.C.; Choi, H.K.; Detterbeck, F.C.; et al. Management of Lung Nodules and Lung Cancer Screening During the COVID-19 Pandemic: CHEST Expert Panel Report. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haineala, B.; Zgura, A.; Badiu, D.C.; Iliescu, L.; Anghel, R.M.; Bacinschi, X.E. Lung Cancer, Covid-19 Infections and Chemotherapy. In Vivo (Brooklyn) 2021, 35, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, J.A.J.; Chhor, A.D.; Begum, H.; Akhtar-Danesh, N.; Finley, C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on non–small-cell lung cancer pathologic stage and presentation. Canadian Journal of Surgery 2022, 65, E496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivanović, D.; Peršurić, Ž.; Agaj, A.; Jakopović, M.; Samaržija, M.; Bitar, L.; et al. The Interplay of Lung Cancer, COVID-19, and Vaccines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasymjanova, G.; Anwar, A.; Cohen, V.; Sultanem, K.; Pepe, C.; Sakr, L.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Lung Cancer at a Canadian Academic Center: A Retrospective Chart Review. Current Oncology 2021, 28, 4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maringe, C.; Spicer, J.; Morris, M.; Purushotham, A.; Nolte, E.; Sullivan, R.; et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça e Silva, D.R.; Fernandes, G.A.; França e Silva, I.L.A.; Curado, M.P. Cancer stage and time from cancer diagnosis to first treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Semin. Oncol. 2023, 50, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.J.X.; Purshouse, K. COVID-19 and cancer registries: learning from the first peak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ost, D.E.; Chauhan, S.; Ramdhanie, L.; Fein, A. Editorial: COVID pandemic and Lung cancer: challenges lead to opportunities. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2021, 27, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conibear, J.; Nossiter, J.; Foster, C.; West, D.; Cromwell, D.; Navani, N. The National Lung Cancer Audit: The Impact of COVID-19. Clin. Oncol. (R Coll. Radiol.) 2022, 34, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanca, M.; Alarcón, R.; Arnau, J.; Bono, R.; Bendayan, R. Non-normal data: Is ANOVA still a valid option? Psicothema 2017, 29, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).