1. Introduction

The CSV files are a special kind of tabulated plain text data container widely used in data exchange, currently there is no defined standard for CSV file’s structure and a multitude of implementations and variants. Notwithstanding the foregoing, there are specifications such as RFC-4180 that define the basic structure of these files, while a useful addendum to this is defined in the specifications of the USA Library of Congress (LOC) [

1]. According to the LOC specifications the CSV simple format is intended for representing a rectangular array (matrix) of numeric and textual values. “It is a delimited data format that has fields/columns separated by the comma character %x2C (Hex 2C) and records/rows/lines separated by characters indicating a line break. RFC 4180 stipulates the use of CRLF pairs to denote line breaks, where CR is %x0D (Hex 0D) and LF is %x0A (Hex 0A). Each line should contain the same number of fields. Fields that contain a special character (comma, CR, LF, or double quote), must be "escaped" by enclosing them in double quotes (Hex 22). An optional header line may appear as the first line of the file with the same format as normal record lines. This header will contain names corresponding to the fields in the file and should contain the same number of fields as the records in the rest of the file. CSV commonly employs US-ASCII as character set, but other character sets are permitted” [

2]. Furthermore, so far to the specifications, in a file may exist: commented or empty records; the tab character (\t) or semicolon (;) as field delimiter; one or more, in exceptional cases, of the characters CRLF, CR, and LF as a record delimiter; quote character escaped by preceding it with a backslash (Unix style).

Given that many public administration portals use CSV files to share information of public interest

1, coupled with the reality that the process of manipulating the information contained in them requires structuring the data in tables and correcting data quality errors, it is necessary to automate tasks as much as possible to reduce the time and effort required to deal with messy CSV data [

3,

4]. The automation problem focuses on seeking the delimiters (also called dialect sniffing) of a given file. Dialect sniffing requires that the field delimiter, record delimiter and escape character be determined [

5].

This problem seems straightforward, but it is by no means simple. If one opts to implement a simple field delimiter counter to choose the one with the most occurrences in the entire file, it is very likely that disambiguation will become impossible if the algorithm is confronted with data that have two or more delimiters with the same number of matches.

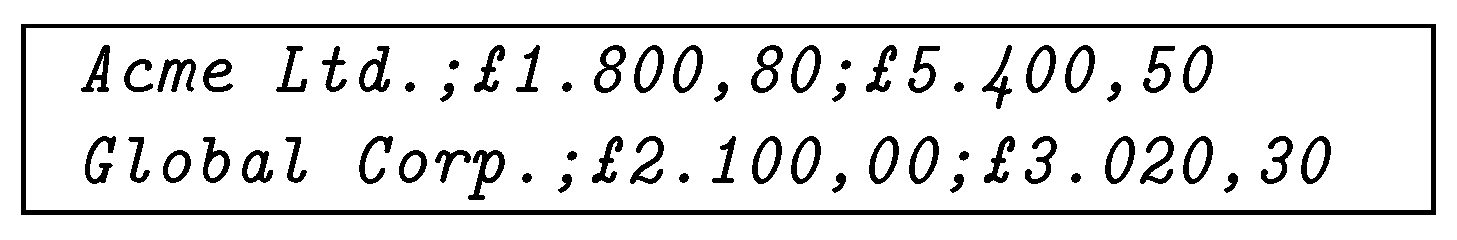

A CSV file with a structure as shown in

Figure 1 is at risk of being misinterpreted, this is illustrated in [

6]. If delimiters are counted, the period or space will be selected as field delimiters because of their three constant occurrences, generating four fields, in the records, as opposed to the two occurrences and three fields generated by the comma and semicolon. Although a well-defined file should have a header row, there are many files on the Internet that do not [

3].

It is a fact that systems that work with CSV files may require the user to set the configuration with which they want the file to be processed, however, when the intention is to analyze data coming from different sources, it is very beneficial to implement a methodology that allows to automatically infer CSV dialects with minimal user intervention.

In this sense, CSV file dialect inference is a fundamental part of data mining, data wrangling and data cleansing environments [

3]. Moreover, dialect detection has the potential to be embedded in systems designed for the new paradigm with the NoDB philosophy, under which it is proposed to make databases systems more accessible to users [

7,

8]. These trends suggest that the traditional practice of considering CSV files outside of database systems is tending to change [

9].

2. Related Work

Dialect detection in CSV files is an understudied field, and there are few sources on the subject. In 2017, T. Döhmen proposed the ranking decision method based on quality hypotheses for parsing CSV files. A similar method is implemented in the DuckDB system [

10]. Another treatment, based on the discovery of the table structures once the information is loaded into the RAM, is ad-dressed by C. Christodoulakis et. al. [

11]. This latter methodology uses the classification of records present in CSV files with a specific heuristic applied to discover and interpret each line of data.

In 2019, G. van den Burg et al, developed the CleverCSV system as a culmination of his research, in which he demonstrated that the methodology significantly improved the accuracy for dialects determination problem compared to tools such as Python’s csv module, or the intrinsic functions of the Pandas package, also in the Python programming language. The implementation of CleverCSV is based on detection of patterns in the structure of CSV records, in addition to data types inference over the fields that compose each record. In this way, the utility applies necessary heuristics to seek the potential dialect for a given CSV file through mathematical and logical operations devised to discern between possible dialects [

5].

In 2023, Leonardo Hübscher et al, presented a research project that led to the development of a software application capable of detecting tables in text files. This research considers the dialect determination of CSV files as a subproblem to be solved in order to seek the dialect that produces the best table [

12].

3. Problem Formulation

Properly formulating the dialect detection problem requires establishing certain fundamental definitions.

Definition 1. (CSV content). Given a CSV file Υ, its content is defined as ξ, where ϵΩ and Ω represents a character set encoded using a given encoder.

As per the CSV content definition, there is a real possibility that a single CSV file contains characters encoded in more than one encoder. For the purposes of this document, it is assumed that all characters share the same encoding.

Given that each file originates from a table to which a format (, ) and the helper function have been applied to produce and write a sequence of human readable characters separated by lines; then from each CSV content is possible to obtain a table so that we can verify .

Definition 2. (CSV table). A table is defined as a set of records composed of a given set of fields, which share data types between corresponding fields across their records. This table can be represented as a data array of fields and records. Thus, its records are defined as ; i.e. a set of fields ; i ϵ. Then, the table can be expressed as ; i.e. a set of records ; i ϵ.

The function is in charge of reading content from the file , while the function parses and transforms the CSV content into a table . The parsing and transformation processes is clearly out of this study scope, so in the following it is assumed that the selected implementation is able to process the tables obtained by parsing a CSV file with the selected tool.

Definition 3.

(CSV dialect). Let Γ be the data table from which the content of file Υ is generated, the dialect ρ is defined as the formatting rule to be applied to produce the output data stream.

So that, by the dialect definition, the following statement is verified:

ϵ Ω.

Definition 4. (CSV dialect determination). Given a CSV file Υ determining the dialect is the act of seeking the dialect that satisfies the statement .

Thus, it can be concluded that for a CSV file , created using a dialect , there exists a dialect that verifies the condition . Therefore, it is verifiable that the content of a CSV file is a function of its dialect.

3.1. Potential Dialect Boundaries

It should be noted that multiple potential dialects can produce similar table outputs that are equal or approximately equal to the source table . Furthermore, shares the same character set as the contents for the CSV file . That is, an element from can be practically any character within domain. Thus, it is necessary to reduce the range of candidate characters involved in dialect detection to streamline the process.

For the purposes of this research, the potential dialect is restricted to

2

4. Table Uniformity

The table uniformity approach is proposed to solve the problem of dialect determination. The method is based on consistency measurement over a table , which has been returned by parsing a CSV file with a dialect , and the dispersion of records along with the inference of raw data types from fields.

Definition 5. (Table consistency). Let be a table generated when parsing a CSV file Υ, using a dialect , the table consistency, denoted by , is a ratio that describes how uniform a table is across its k fields and its n records.

Definition 6.

(Records dispersion). Let Φ be the sets of records from table , generated when parsing a CSV file Υ using a dialect , the records dispersion, denoted by , is a measure describing the magnitude of the change in the records composition throughout the table.

These definitions are based on the fact that tables, in general, have a defined structure with persistent k fields in its n records.

The two measurements that define the table uniformity parameter

are related to the structure of records

from a table

. Where

is a direct function of the standard deviation of fields, and

is a function measuring the weighted dispersion in records structures as a factor of the statistical segmented mode

3.

Where, for a given table , is the number of fields standard deviation across records; represents the count of times number of fields changes between records; R is the statistical range for the number of fields over records; M is the segmented mode, describing the largest number of times the record structure is sequentially preserved within the table, and is the records variability factor.

The definitions provided propose a concept diametrically opposed to that used in most solutions, since it discourages data dispersion, i.e. records with a higher number of fields/columns are only favored if their record structure is uniform.The parameter indicates the degree of consistency for the records in a table, while is a fine-grained measure of the dispersion and inconsistency within the records. This quality allows the new method to discern between data tables by inferring uniformity in two senses: consistent and invariant records with little dispersion in their structure. The parameter ranges from , being 1 for those tables with consistent records; while ranges from , being 0 for those tables with invariant record structure and without dispersion.

5. Type Detection

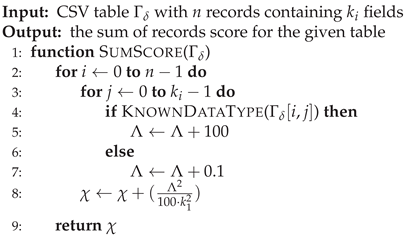

Data type detection is the core basis of the implemented methodology. Recognition of data types over fields from each record allows us to collect information about the contents of a given table. In this context, the records scoring, denoted as , is computed as

Where is a score for the ith field in from the table . If the type of the ith field is known, , otherwise.

For the purposes of this paper, the following field types are generally considered to be known:

Time and date: matching regular dates and time format, as well stamped ones like MM/DD/YYYY[YYYY/MM/DD] HH:MM: SS +/- HH:MM.

Numeric: matching all numeric data supported by the implementation language selected.

Percentage.

Alphanumeric: matching numbers, ASCII letters and underscore.

Currency.

Especial data: like “n/a” or empty strings.

Email.

System paths.

Structured scripts data types: matching JSON arrays and data delimited by parentheses, curly and square brackets.

Numeric lists: matching fields with numeric values delimited with common separator character.

URLs.

IPv4.

Al other fields will be scored as unknown type.

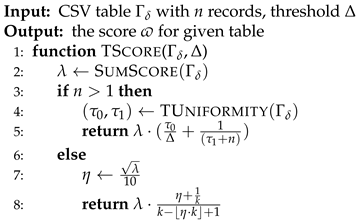

6. Table Scoring

Once table uniformity for records from the table , which has been generated by reading a CSV file using a dialect , and the score are computed, the table score, denoted as , is computed as

Where is a threshold indicating the expected number of records to be imported from the CSV file which contains a number of records m. For , and an appropriate selection of , will generate a table where ; therefore, by the definition stated, the table score is in the range .

In the case we have

Where is a discriminant to ensure the exclusion of false positives with a single record.

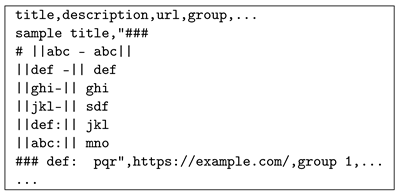

7. Determining CSV File Dialects

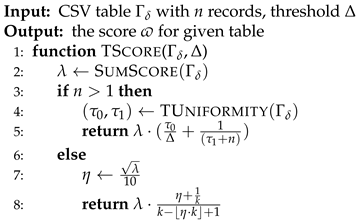

This section shows the core algorithms on which the methodology presented in this research is based, complementary algorithms are listed in the

Appendix A.

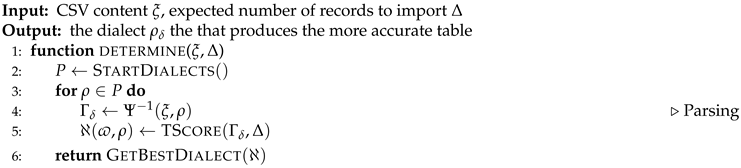

The main pseudocode for dialect determination is listed in Algorithm 1. At line 2 the set of predefined dialects are initialized; then, in line 4, a table

is created by parsing the CSV content

with each

dialect.

|

Algorithm 1 Dialect Determination |

|

At this point, it becomes clear that the selection of a robust parser is of utmost importance in order to obtain the best results even on messy files. In line 5, the output table is scored and this result is saved within the current dialect in the collection ℵ. At line 9, the dialect that gets the highest scored table is selected.

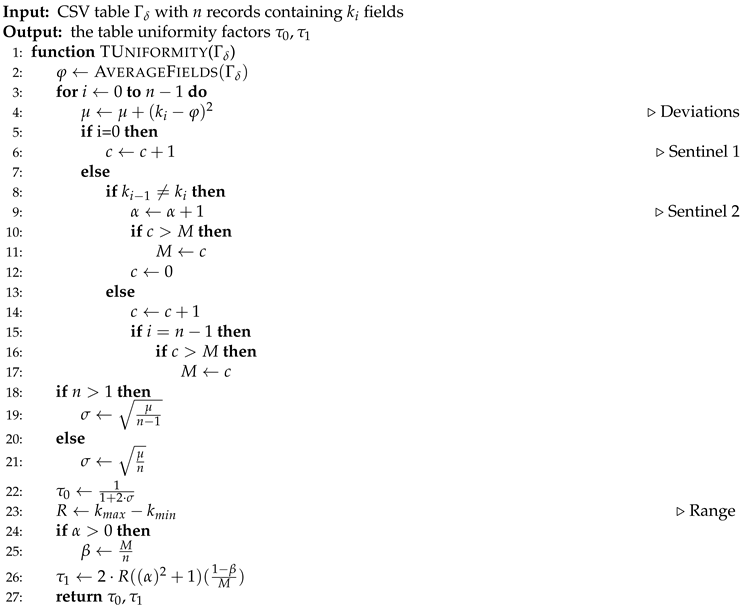

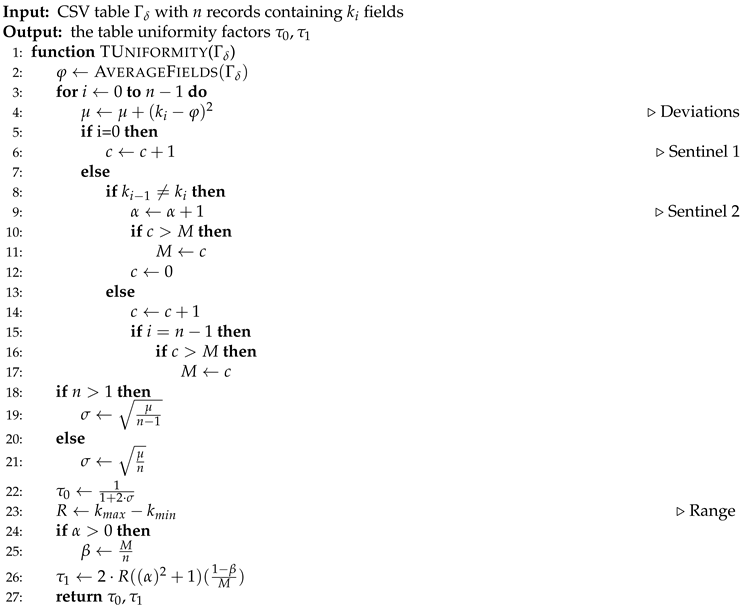

The table uniformity procedure is outlined in Algorithm 2 pseudocode. The method uses a set of sentinels to measure table inconsistency through monitoring table changes over parsed records.

The parameter

is derived from the standard deviation that indicates how uniformly the fields count are grouped around the average number of fields contained in the parsed records, resulting in an appropriate measure to qualify the structure of a table [

13]. However, when there are two or more dialects with a small variance, the

parameter is not decisive. It is in this situation where the

parameter provides support by penalizing tables with variations in its records structures, and whose structure resembles sparse data that do not maintain consistency.

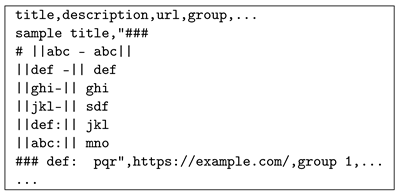

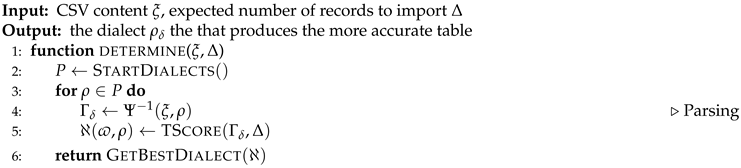

The following illustration shows a preview from the modified content of one file used during the testing phase. It was published in the CleverCSV repository on GitHub

4. The star character has been replaced by the vertical bar “|” to include in the detection a potential dialect with this character. As the author points out, the CSV file is comma delimited, using double quotes as the quote and escape character, then this file is compliant with RFC-4180 specifications. When running dialect detection, CleverCSV gets the vertical bar “|” as the delimiter because this field pattern gets a

score vs a

from patterns with the “,” character as delimiter. This behavior is because the implemented logic heavily weights the delimiter count over the detected data types, where dialects containing the comma as delimiter obtain a type score of

against the type score of

obtained by dialects with the vertical bar as delimiter.

By executing the algorithms presented in this research, we get the following for dialects with the vertical bar as the delimiter

,

,

, and

. For the comma we get

,

,

, and

. Then the comma “,” character is selected as delimiter.

|

Algorithm 2 Table Uniformity |

|

8. Experiments

It was decided to code the new method and integrate it with CSV Interface

5, a VBA CSV file parser. Thus, the new CSV dialect determination method will be available in a widespread programming language without over-investing efforts. Additionally Python code has been written to run the tests for CleverCSV. The code repository is currently available on GitHub

6.

The new solution was tested on two datasets, both on GitHub: the one provided by Gerardo Vitagliano et al, and available in the Pollock framework repository; the other provided by G. van den Burg in the CleverCSV repository. For the first dataset, one or two polluted CSV file per pollution case are included for testing, all the 99 survey having at least one pollution case as described in the aforementioned study (excluding empty ones by the fact infinite dialects can be produce no payload files [

14]). In addition, the dataset was enriched with data from the OpenRefine

7 testing, CleverCSV failure cases and other files used at development phase serves as testing samples. In total, the solution was tested against 148 CSV files (104 MB of data) for the simple Pollock testing.

The second dataset is composed of the 256 CSV files that CleverCSV could not accurately determine when conducting the research that led to the tool development [

15]. At the time of this research, 244 of these files were available online. A filter was applied to exclude from the dataset all files with a structure that did not visually look like a CSV. After filtering, the dataset ended up with 179 CSV files (79 MB of data), which were used as a ground truth of our dialect detection method. Additionally, these files were subdivided to extract from them a set of CSVs that we can call "messy"; the structure of these being unconventional and whose dialect is much more difficult to infer. This last step is required since the dataset contains files that fall under the “normal forms” classification implemented in CleverCSV, which refers to CSV files with such a simple structure that they allow the determination of their dialects using only data inference

8.

To set up the tests, all files were manually annotated, using a separated set of annotation files, in order to verify the validity of detected dialects. In this context, we define the accuracy of dialect detection as the ratio of correctly detected dialects to the total number of test files with no error after execution.

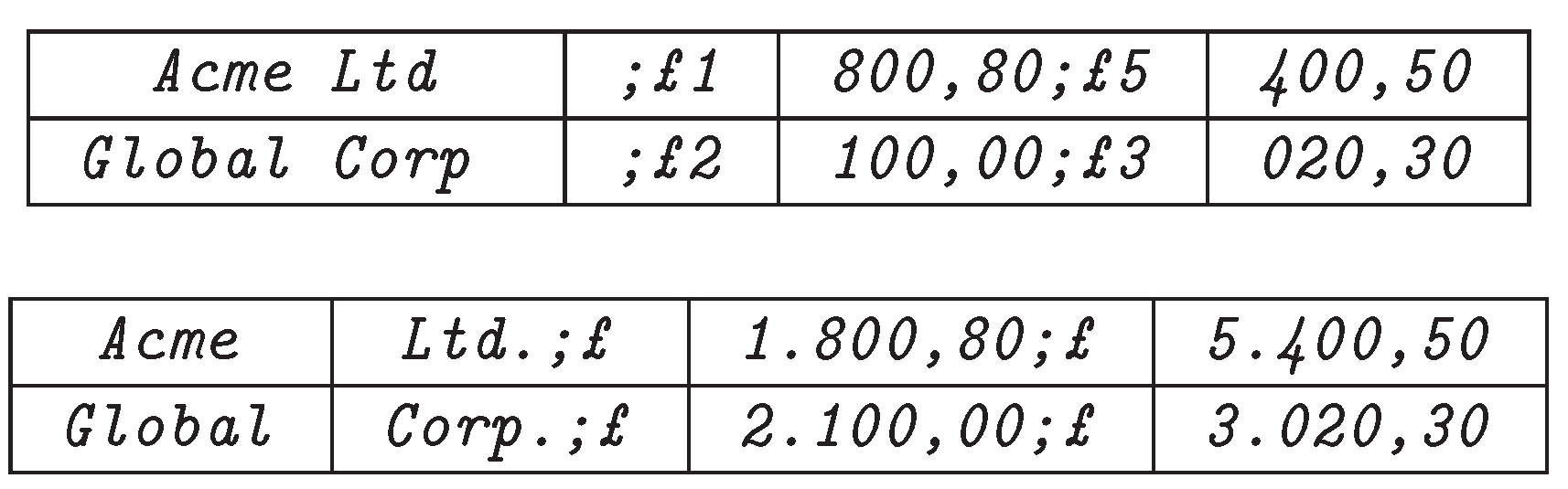

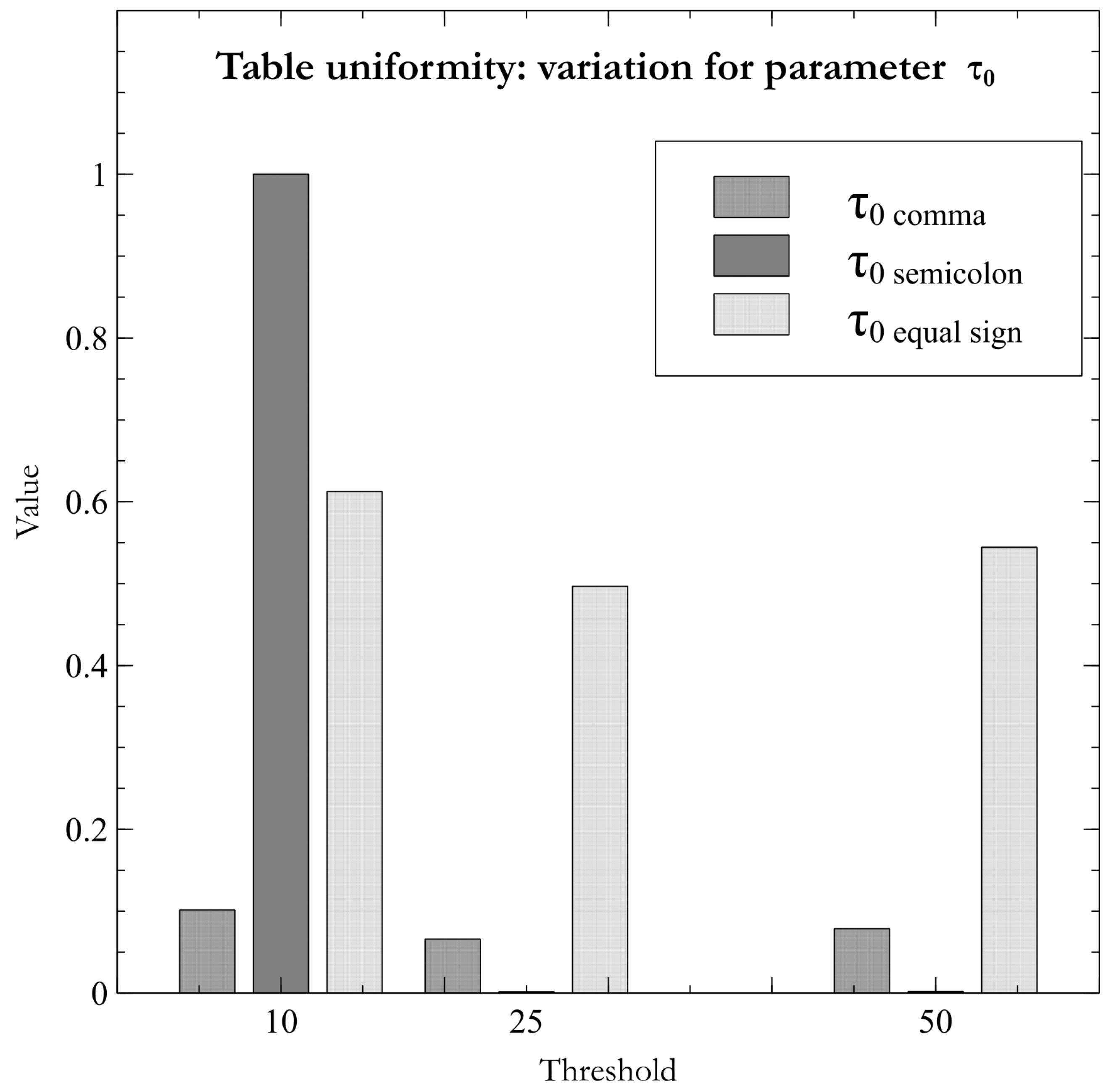

8.1. Dialect Detection Accuracy

The

Table 1 shows the results after running the dialect detection tests over the simple Pollock testing dataset. It can be seen that the new proposed heuristic gets a perfect score when using a table with a threshold of fifty records (50R) to be imported from the target CSV file.

When using tables of ten or twenty-five records (10R, 25R) for dialect determination, the proposed method was not able to determine dialect of the

“dd_Wickenburg_nobmp_623.csv” file for the testing dataset. This file has been selected to show the variation of certainty as the considered table size increases across computations. As can be seen in the

Figure 3, when the proposed heuristic is applied, it is settled that delimiter is the equal sign “=”, since the dialects containing it divide each record into known data types: an alphanumeric field/column and a field with structured data delimited by square brackets. Increasing the table size to twenty-five (25R) induces the heuristic begins to highlight the semicolon “;” as a possible field delimiter character. Finally, the semicolon is correctly detected as a delimiter when the threshold of fifty records (50R) in the table is specified. This behavior demonstrates that the proposed methodology is strongly related to changes in the structure of tables used in dialect inference.

The results obtained after running the tests over dataset from CleverCSV are shown in

Table 2. In this dataset the percentage of incorrectly detected dialects became approximately 10%. This metric indicates the presence of CSV files with unconventional structures. Notwithstanding the foregoing, dialect detection improves by 9.81% compared to CleverCSV.

CleverCSV running in verbose mode indicates that the tool failed to read 37 of the test files with errors related to the file encoding. These files, along with ones listed as “normal forms”, were excluded from the dataset, producing a really messy subset of CSV files. Executing the tests over this selective filtered subset yields the results shown in

Table 3. For this subset of files there is a slight increase in the rate of incorrect detections, preserving the 10% improvement of the new methodology over CleverCSV. On average, the heuristic proposed in this research shows an improvement of 7.51% compared to CleverCSV, outperforming the latter with 10% when handling messy CSV files.

9. Discussion

By looking closely at the results obtained, it can be deduced that there are two main categories that influence the certainty of determined dialects: the type of heuristics used, the CSV file parser behavior while producing tables using a certain dialect. In this section both categories are discussed in order to briefly qualify the experiments results.

9.1. Heuristic

In contrast to CleverCSV, in whose heuristic the detection of data types serves as a factor to scale down the score obtained by a certain pattern; the table consistency method uses data detection as a base score to be narrowed using the table consistency and data dispersion parameters. The results therefore indicate that the factors obtained are not commutative.

Since data type detection is a fundamental part of both methods, it is necessary to include a wide range of known data typologies. This factor is undoubtedly determining in dialect detection. According to Mitlohner’s research [

4], with a base of 104,826 CSV files, the vast majority of data commonly stored in this type of files are numeric, tokens (words separated by spaces), entities, URLs, dates, alphanumeric fields and general text, so these data types must be recognized. Additionally, in the field of programming, there are other types of data frequently dumped in CSV files, namely: structured data with the Regex pattern

, numerical lists, tuples, arrays among others.

It is worth mentioning that dialect detection is prone to failure when the CSV file is composed of unknown data types. In these cases, the table uniformity tends to select dialects that produce registers with a single field. When reviewing the cases where CleverCSV was not able to determine the dialect, it has been observed that the common denominator has been the high count of a potential delimiter with more occurrences than the expected delimiter. In this sense, both solutions have poor performance when the space character appears in the list of potential delimiters.

There are files where the threshold of records in the target table is decisive; however, tests have found that the dialect of some files is determined incorrectly as the value of this parameter is increased and more records are loaded into the table. This peculiarity allows us to conclude that the first records can adequately describe the structure of CSV files, avoiding, to a certain extent, the need to read the whole file. In this particular, it was found that CleverCSV had a running time of approximately 19 minutes before completing the tests it was subjected to. The results obtained lead to conclude that the default option when detecting dialects in CSV files should be to read only a sample of the file instead of reading its entire contents.

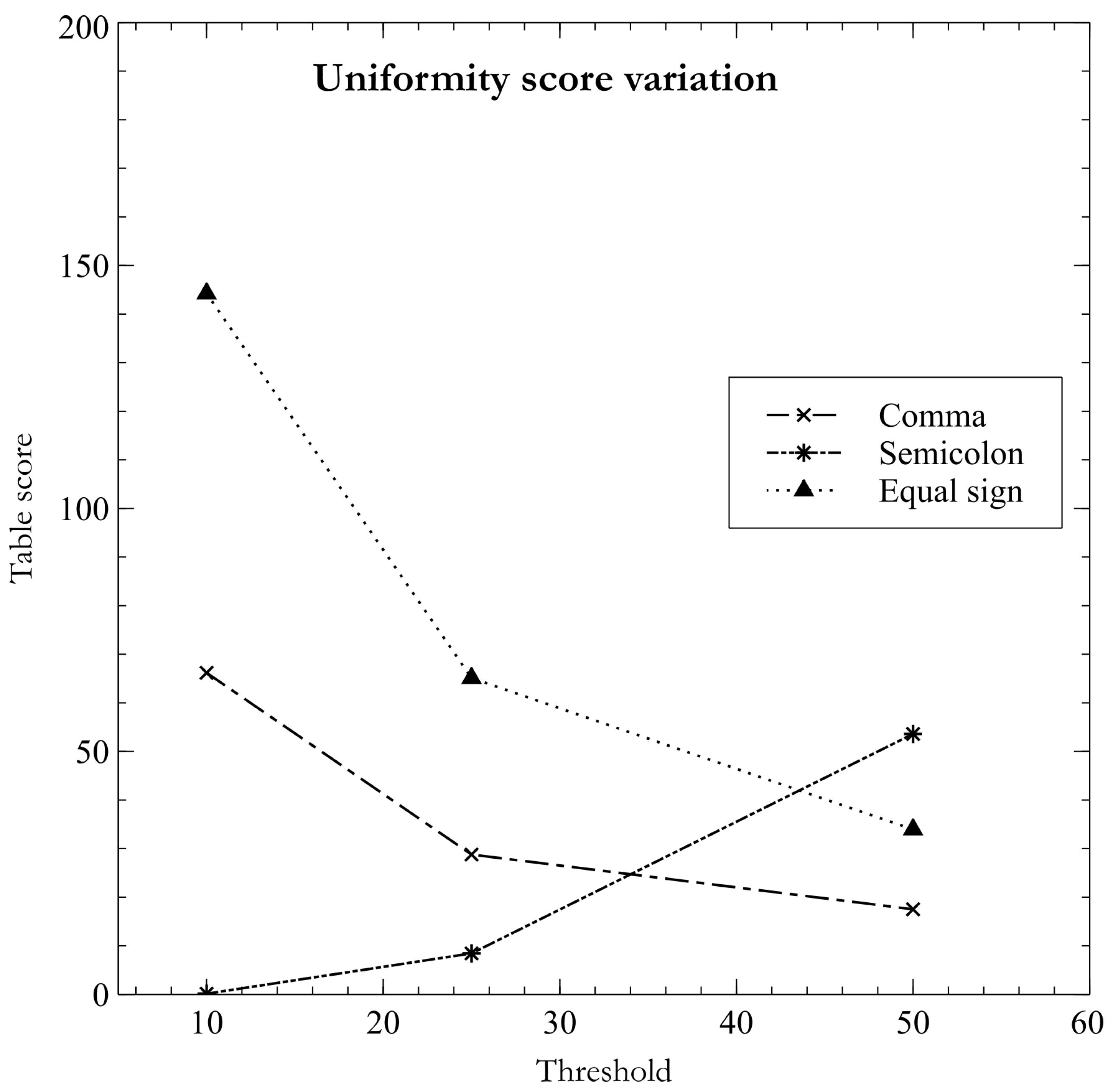

As pointed out earlier, the table uniformity method prefers grouped data over those that appear to be sparse data. In these cases, detection tends to depend exclusively on the data types detected in the records. This fact is evidenced by plotting the values of the uniformity parameter .

Looking at

Figure 4, it can be seen that, even though the score obtained by the semicolon dialect is very close to zero, the value of

is maximum. In contrast, this value fluctuates to nearly zero for the dialect containing semicolon; it remains almost unchanged among the dialects using other fields delimiters characters. In these cases, the dialect determination is relegated to data type detection and fine-grained monitoring of changes in table structures through the

parameter. It is noted that the parameters

and

work together for well-defined tables, selectively overriding each other when processing tables with poorly defined data structures.

9.2. CSV Parser Basis

The accuracy of dialect determination is intimately related to the way CSV parsers behave when confronted with atypical situations. This is because heuristics use these results to infer the configuration that returns the most suitable data structures.

One of the capabilities required for dialect determination is the recovery of data after the occurrence of a critical error. This is the case when import CSV files where there is no balanced quotation count. This situation breaks the RFC-4180 specifications and causes an import error in almost all solutions intended to work with CSV files. In this sense, the recovery of this error should include a specific message after which the loading of information should continue until the whole file is processed.

Since the determination of dialects can be done with a few records received from a CSV file, there is a probability that some of the parameters that compose the dialect cannot be determined properly. Given this reality, it is preferable that CSV parsers be able to convert between one escaping mechanism and another instead of making the escape character mutually exclusive as established in the most relevant proposals on these topics [

16]. This results in the correct interpretation of escape sequences that use the “∖” for those files in which a quote character has been detected as part of their dialect.

Appendix A. Algorithms Pseudocode

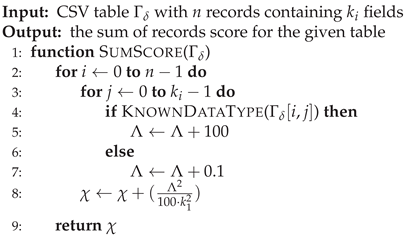

|

Algorithm 3 Table Score |

|

|

Algorithm 4 Sum of Records Score |

|

References

- Yakov Shafranovich. Common Format and MIME Type for Comma-Separated Values (CSV) Files. IETF. 2005. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc4180/ (visited on 07/23/2021).

- Library of Congress.CSV, Comma Separated Values (RFC 4180). LOC. Feb. 11, 2020. https://www.loc.gov/preservation/digital/formats/fdd/fdd000323.shtml.

- Sutton, C.; Hobson, T.; Geddes, J.; Caruana, R. Data Diff: Interpretable, Executable Summaries of Changes in Distributions for Data Wrangling. Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. ACM, pp. 2279–2288. [CrossRef]

- Mitlohner, J.; Neumaier, S.; Umbrich, J.; Polleres, A. Characteristics of Open Data CSV Files. 2016 2nd International Conference on Open and Big Data (OBD). IEEE, pp. 72–79. [CrossRef]

- van den Burg, G.J.J.; Nazábal, A.; Sutton, C. Wrangling messy CSV files by detecting row and type patterns. 33, 1799–1820. [CrossRef]

- Döhmen, T.; Mühleisen, H.; Boncz, P. Multi-Hypothesis CSV Parsing. Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Scientific and Statistical Database Management. ACM, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Alagiannis, I.; Borovica-Gajic, R.; Branco, M.; Idreos, S.; Ailamaki, A. NoDB: efficient query execution on raw data files. 58, 112–121. [CrossRef]

- Karpathiotakis, M.; Branco, M.; Alagiannis, I.; Ailamaki, A. Adaptive query processing on RAW data. 7, 1119–1130. [CrossRef]

- Idreos, S.; Alagiannis, I.; Johnson, R.; Ailamaki, A. Here are my data files. Here are my queries. Where are my results? Proceedings of 5th Biennial Conference on Innovative Data Systems Research, pp. 57–68.

- Dutch Stichting DuckDB Foundation. DUCKDB. Version 0.9.2. Amsterdam NL, 2023. https://duckdb.org/docs/archive/0.9.2/ (visited on 02/04/2024).

- Christodoulakis, C.; Munson, E.B.; Gabel, M.; Brown, A.D.; Miller, R.J. Pytheas: pattern-based table discovery in CSV files. 13, 2075–2089. [CrossRef]

- Hübscher, L.; Jiang, L.; Naumann, F. ExtracTable: Extracting Tables from Raw Data Files. ISBN: 9783885797258 Publisher: Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V. [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, M.F.; Yousif, A.E. Properties of the Standard Deviation that are Rarely Mentioned in Classrooms. 38. [CrossRef]

- Vitagliano, G.; Hameed, M.; Jiang, L.; Reisener, L.; Wu, E.; Naumann, F. Pollock: A Data Loading Benchmark. 16, 1870–1882. [CrossRef]

- Petricek, T.; Burg, G.J.J.V.D.; Nazábal, A.; Ceritli, T.; Jiménez-Ruiz, E.; Williams, C.K.I. AI Assistants: A Framework for Semi-Automated Data Wrangling. 35, 9295–9306. [CrossRef]

- Rufus Pollock. Data Package (v1). CSV Dialect. Feb. 20, 2013. url: https://specs.frictionlessdata.io/csv-dialect/ (visited on 05/10/2023).

| 1 |

An analysis of a 413 GB data body found CSV files available for download on 232 portals. |

| 2 |

In most applications the record delimiter is not considered, as modern systems handle new lines discrepancies internally. |

| 3 |

Segmented mode refers to the use of sample segments, which are defined as the data undergoes dispersion. |

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).