Submitted:

15 February 2024

Posted:

15 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

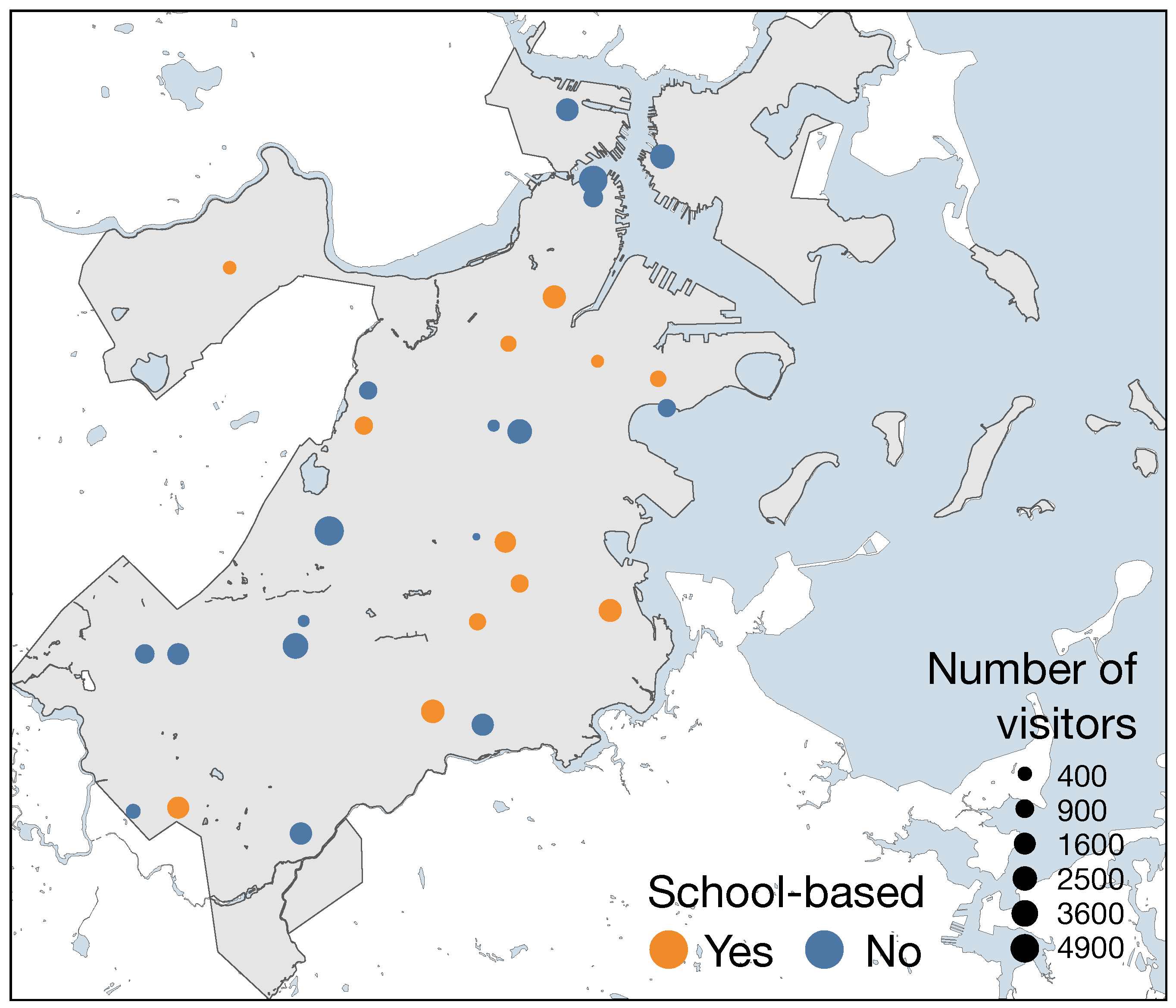

2.1. Data

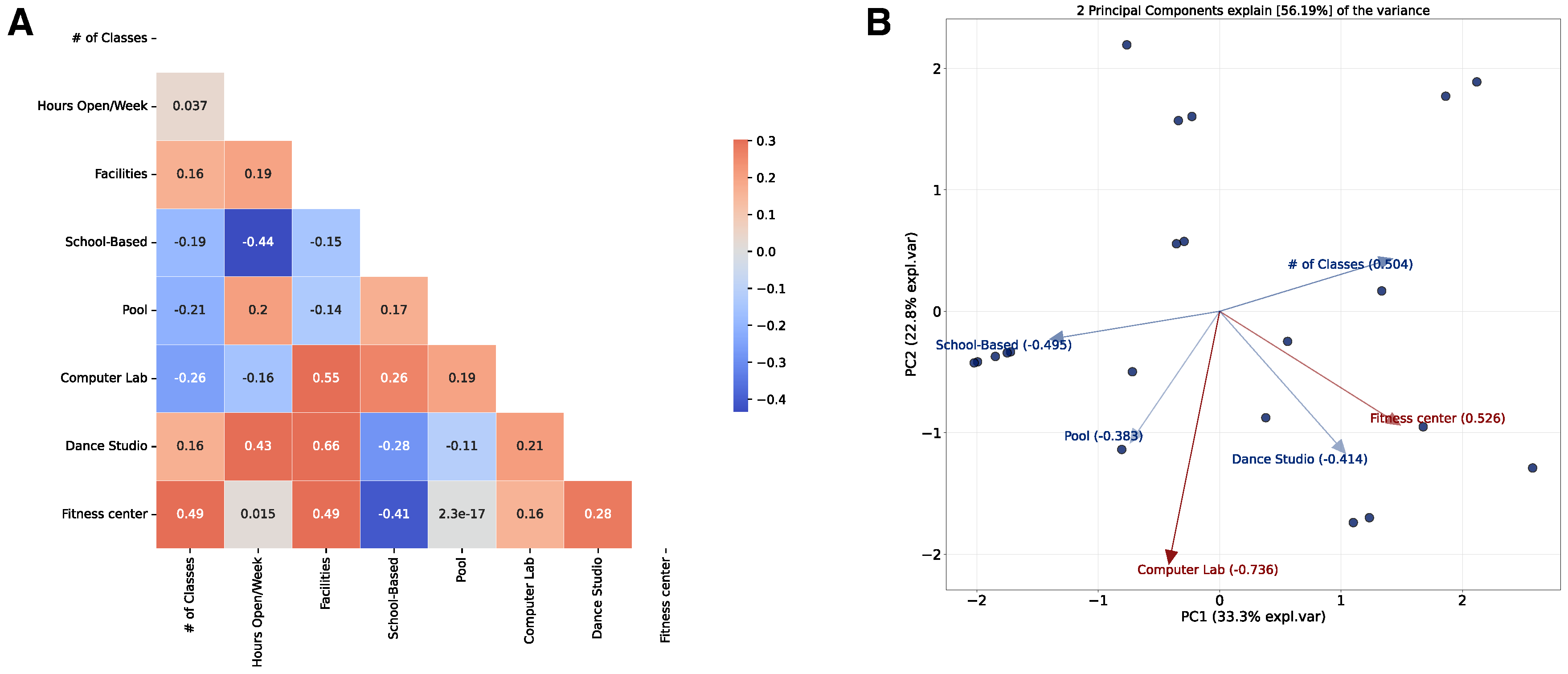

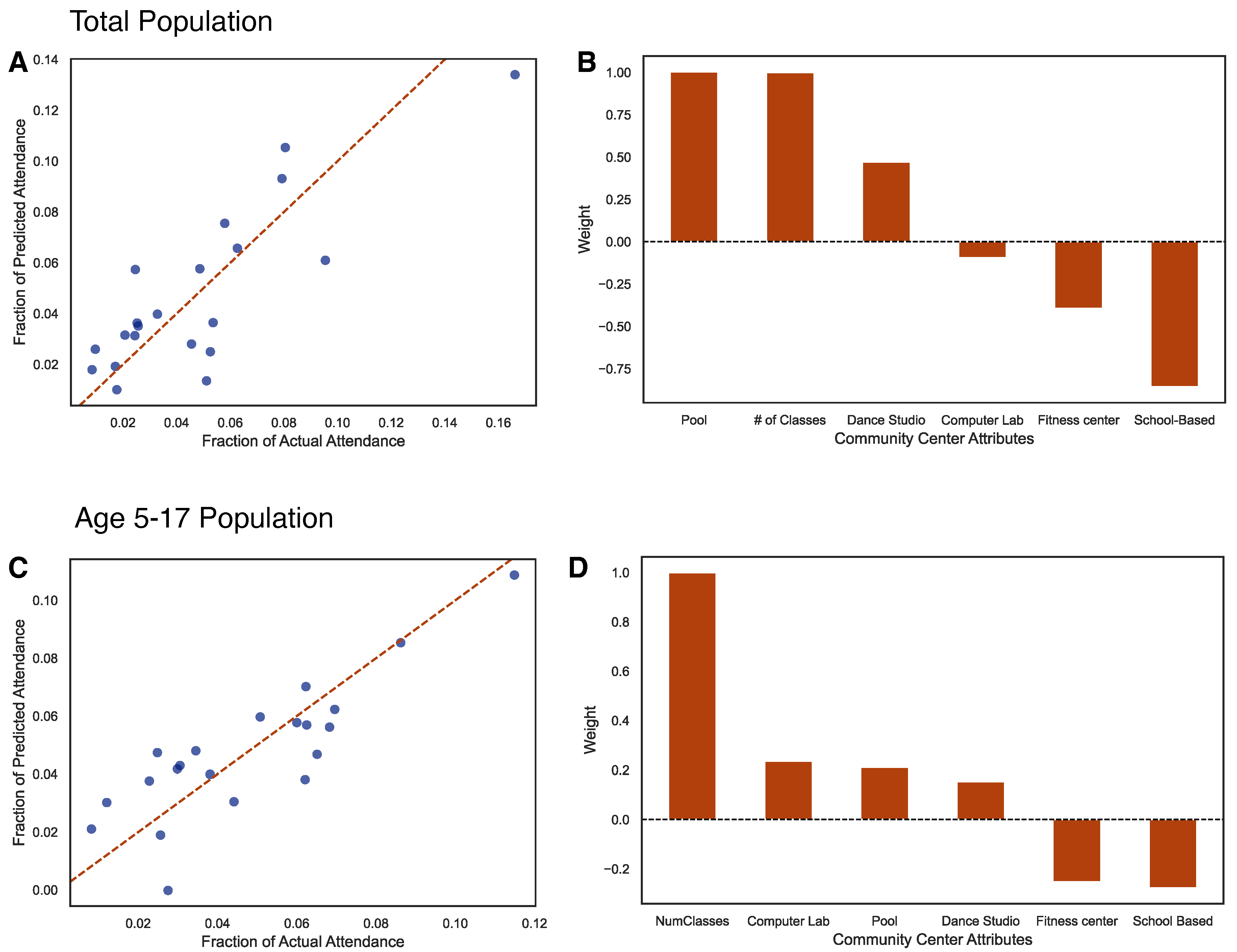

2.2. Model

2.3. Optimization of the Model

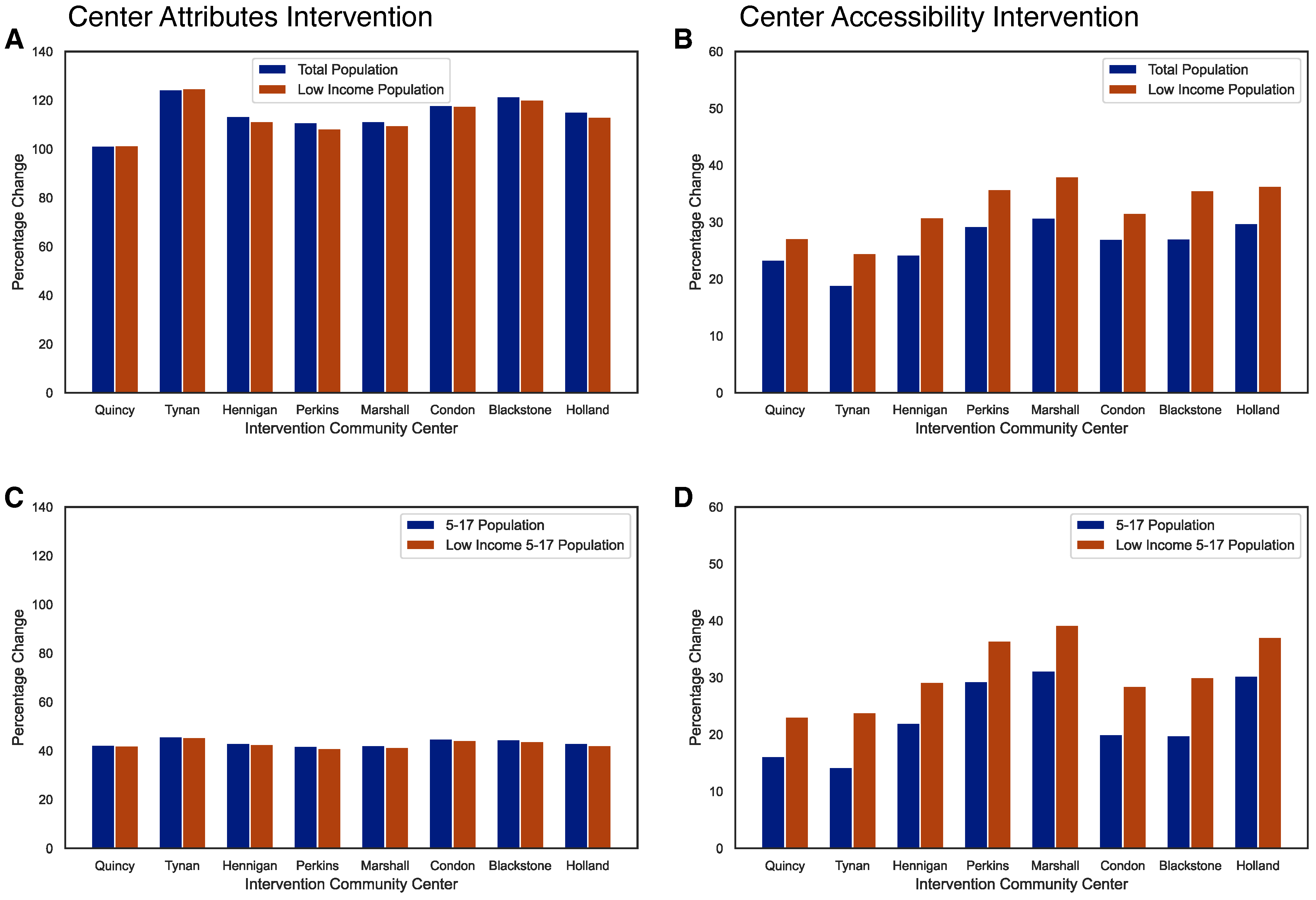

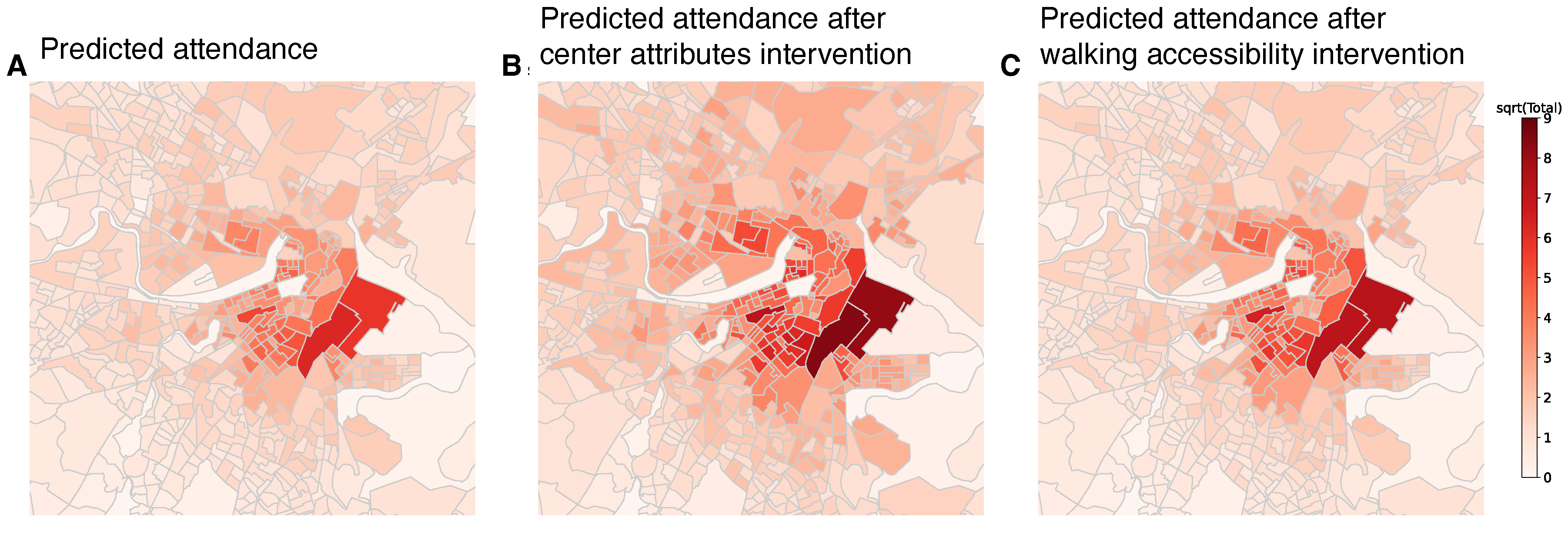

3. Interventions

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Acknowledgments

References

- Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. 21st Century Community Learning Centers (CCLC) Grant Program, Summer Reports. Available online: https://www.doe.mass.edu/21cclc/ (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Afterschool Alliance. What does the research say about 21st Century Community Learning Centers? Available online: http://afterschoolalliance.org//documents/What_Does_the_Research_Say_About_21stCCLC.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- of Boston, C. of Boston, C. Boston Centers for Youth and Families. Available online: https://www.boston.gov/departments/boston-centers-youth-families (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Huff, D.L. Parameter estimation in the Huff model. Esri, ArcUser 2003, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sevtsuk, A.; Kalvo, R. Patronage of urban commercial clusters: A network-based extension of the Huff model for balancing location and size. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2018, 45, 508–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R.J. Principles of urban retail planning and development; John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- Doorley, R.; Noyman, A.; Sakai, Y.; Larson, K. What’s Your MoCho? Real-time Mode Choice Prediction Using Discrete Choice Models and a HCI Platform. Proceedings of the UrbComp 2019, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, D.; Azzato, S.; Elkatsha, M.; Defrain, E.m.; Alonso Pastor, L.; Larson, K. Predicting Behavioral Changes as a result of land-use Modifications in Auto-Centric Communities: Data Driven Discrete Mode Choice Modeling for Dallas TX. Proceedings of SUPTM 2024 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, L.; Zhang, Y.R.; Grignard, A.; Noyman, A.; Sakai, Y.; ElKatsha, M.; Doorley, R.; Larson, K. Cityscope: A data-driven interactive simulation tool for urban design. Use case volpe. Unifying Themes in Complex Systems IX: Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Complex Systems 9. Springer, 2018, pp. 253–261.

- Grignard, A.; Alonso, L.; Taillandier, P.; Gaudou, B.; Nguyen-Huu, T.; Gruel, W.; Larson, K. The impact of new mobility modes on a city: A generic approach using abm. Unifying Themes in Complex Systems IX: Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Complex Systems 9. Springer, 2018, pp. 272–280.

- Barbosa, H.; Barthelemy, M.; Ghoshal, G.; James, C.R.; Lenormand, M.; Louail, T.; Menezes, R.; Ramasco, J.J.; Simini, F.; Tomasini, M. Human mobility: Models and applications. Physics Reports 2018, 734, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grignard, A.; Macià, N.; Alonso Pastor, L.; Noyman, A.; Zhang, Y.; Larson, K. Cityscope andorra: A multi-level interactive and tangible agent-based visualization. Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Systems, 2018, pp. 1939–1940.

- United States Census Bureau. 2015-2019 American Community Survey 5-year Estimates. 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Ibargoyen, T.M.; Barrenechea, P.; Elkatsha, M.; Alonso Pastor, L.; Larson, K. A Methodology To Quantify Demands And Space Requirements Of Amenities And Services For A Given Community. Use Case: Volpe Development, Kendall Sq. Proceedings of SUPTM 2024 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, C.A.; Castañer, E.; Sevtsuk, A. The amenity mix of urban neighborhoods. Habitat International 2020, 106, 102205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Brett, M.; Wilson, J.; Millman, K.J.; Mayorov, N.; Nelson, A.R.J.; Jones, E.; Kern, R.; Larson, E.; Carey, C.J.; Polat, İ.; Feng, Y.; Moore, E.W.; VanderPlas, J.; Laxalde, D.; Perktold, J.; Cimrman, R.; Henriksen, I.; Quintero, E.A.; Harris, C.R.; Archibald, A.M.; Ribeiro, A.H.; Pedregosa, F.; van Mulbregt, P.; SciPy 1.0 Contributors. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [CrossRef]

| Community | # of | Hours | School- | Computer | Dance | Fitness | ||

| Center | Classes | Open/Week | Facilities | Based | Pool | Lab | Studio | Center |

| Quincy | 84 | 58 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Blackstone | 21 | 58 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Nazzaro | 183 | 60 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Condon | 22 | 58 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Tobin | 61 | 73 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mason Pool | 82 | 66 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Charlestown | 59 | 40 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Tynan | 73 | 50 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Curley | 54 | 78.5 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Paris Street | 73 | 68 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hennigan | 61 | 70 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Curtis Hall | 266 | 78 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Holland | 18 | 58 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Marshall | 43 | 50 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Perkins | 57 | 68 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Gallivan | 47 | 68 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Menino | 38 | 55 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Flaherty Pool | 66 | 78 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Roche | 198 | 73 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Hyde Park | 61 | 60 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ohrenberger | 264 | 40 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).