Introduction

Species distribution refers to the spatial arrangement of various species throughout the world. It is a key concept in ecology and biogeography, and is influenced by a variety of factors, such as climate, topography, resource availability, competition with other species, and the dispersal ability of each organism (Chuine, 2010; Kissling et al., 2018; Bakx et al., 2019). Understanding species distribution is fundamental for biodiversity conservation, as it helps to identify priority areas for ecosystem protection and management (Da Silva et al., 2020; Piccolo et al., 2020; Srinivasulu et al., 2021). Thus, the study of these patterns can provide valuable information on the ecological mechanisms that govern the spatial distribution of threatened species.

Species distribution models (SDM) are tools and approaches used in biodiversity conservation to predict and understand the potential spatial distribution of species as a function of environmental and geographic variables (Peterson and Soberón, 2012; Piccolo et al., 2020; Srinivasulu et al., 2021). These models are based on the idea that the presence or absence of a particular species within a given region is closely linked to specific environmental variables (Phillips and Dudík, 2008). However, acquiring such data can pose logistical and costly challenges for some species. Consequently, MDS allows leveraging existing data, such as observational records, to extrapolate and make inferences about distribution in areas where direct information may be limited (Gaubert et al., 2002; Meza-joya et al., 2018; Da Silva et al., 2020).

The long-tailed rattlesnake

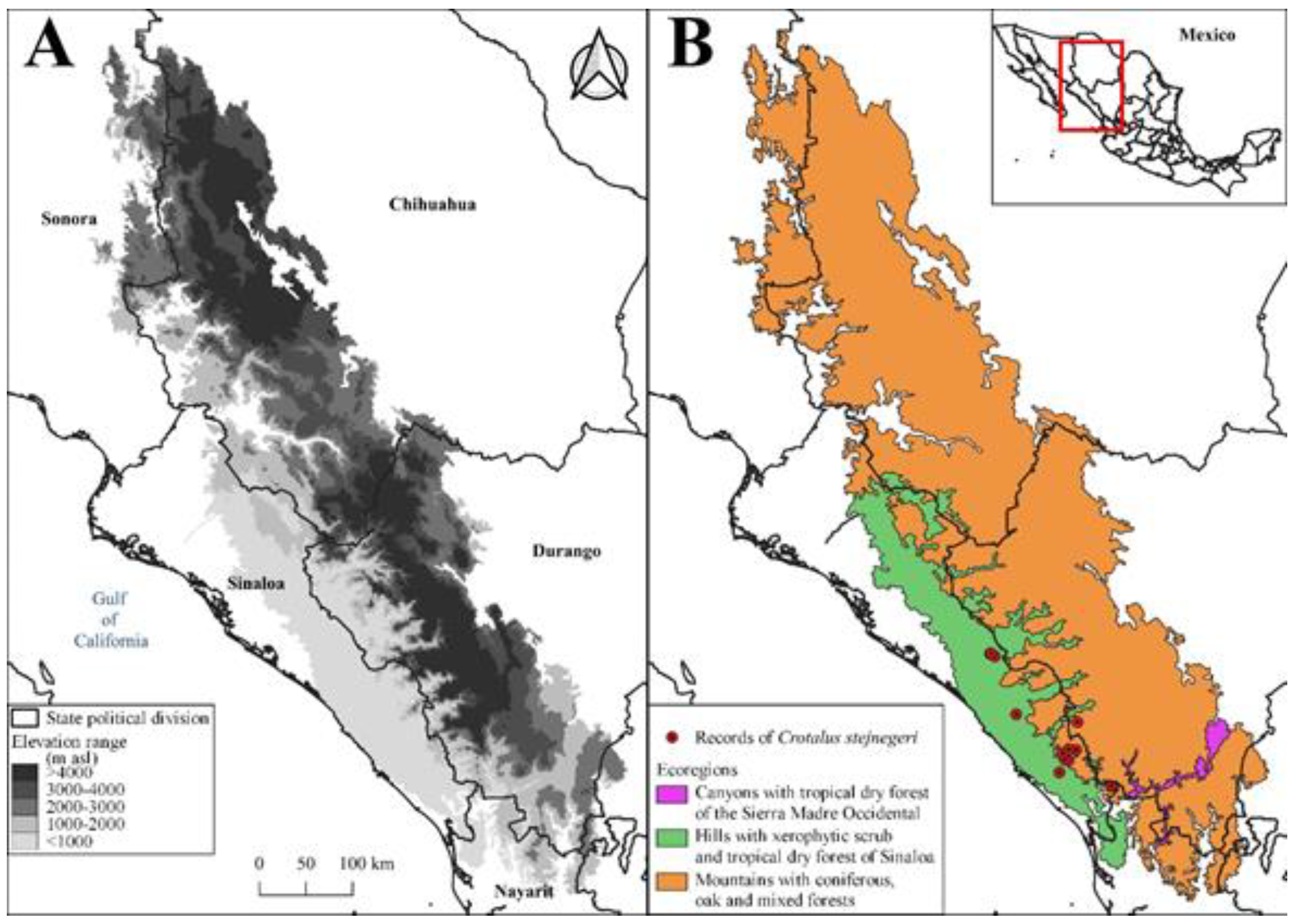

Crotalus stejnegeri (Dunn, 1919) is a species endemic to Mexico (

Figure 1). It is classified as vulnerable (VU) by the IUCN and threatened (A) by the Mexican species protection standard (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010). This species is considered rare because it has not been collected since 1976 and has a restricted distribution (Armstrong and Murphy, 1979). Van der Heiden and Flores-Villela (2013) provided a geographic review of

C. stejnegeri collections to clarify its distribution in Sinaloa and Durango, states where records of the species exist. The authors acknowledge that

C. stejnegeri is present in southern Sinaloa and southwestern Durango (only in the locality of Ventanas). However, they dispute the record in Durango’s Yamoriba area, citing an elevation range (1780 m asl) deemed too high for the species, as noted by Robert Meidinger (pers. comm., 31 July 2011 in Uetz et al., 2023). Interestingly, Van der Heiden and Flores-Villela (2013) did not address the historical records of the species in Nayarit. In the herpetofauna listing of Nayarit, Woolrich-Piña et al. (2015) omitted

C. stejnegeri due to a lack of photographic evidence and supporting documentation its presence in the state. It is noteworthy that also failed to mention that the ENCB-IPN 8307 collection record near San Blas is a juvenile

Crotalus basiliscus (pers. comm., Jesús Alberto Loc Barragán, after examining collection records from Nayarit).

Reyes-Velasco et al. (2010) proposed that the range of C. stejnegeri may be much larger than currently known. The authors provide several explanations supporting this assertion, including the existence of illicit operations and the limited availability of passable routes, particularly challenging to traverse during the wet season in these regions. Additionally, anthropogenic factors with the potential to impact its habitat, such as agriculture, livestock grazing, deforestation, and mining, are identified (Castro-Bastidas et al., 2022; Jacobo-González et al., 2023; unpublished data; HACB). The presence of C. stejnegeri in southern Sinaloa and the neighboring states of Durango and Nayarit is believed to be probably greatly underestimated (Van der Heiden and Flores-Villela, 2013).

Presently, there is a 70% increase in C. stejnegeri records, facilitated by the contributions of citizen science in the state of Sinaloa (45 records from GBIF, 2024, compared to 13 collections in Van der Heiden and Flores-Villela, 2013). Additionally, recent information on the biology and ecology of the species is now available (Van der Heiden, 2019; 2021). Here, we present a SMD for C. stejnegeri, a species with limited data, to predict its potential distribution.

Methodology

Data source. Records of C. stejnegeri were obtained after a review of records in scientific collection databases (Global Biodiversity Information Facility, Vertnet), citizen science observations (iNaturalist) and literature records (Van de Heiden and Flores-Villela, 2013; Van der Heiden, 2019). Each record underwent verification, and those lacking coordinates were assigned one if a reference locality was provided via Google Earth. Records without coordinates or a reference locality were excluded. To mitigate spatial bias, a nearest neighbor analysis was conducted (expected mean distance 0.145, index 22042.762, and observed mean distance 3209.109). Duplicate records were eliminated because clustering of the data was obtained (Abdelaal et al., 2019). Records from Yamoriba in Durango and San Blas in Nayarit were not considered due to geographic and misidentification concerns associated with these records.

On the other hand, the selection of environmental variables was obtained from the climatological database CHELSA v2.1 (Brun et al., 2022). This database encompasses 19 traditional bioclimatic variables with a 30-second resolution (~1 km), and its data span from 1980 to 2018 (

Table 1). These variables were chosen primarily because the majority of

C. stejnegeri records are post-2000. Additionally, an elevation raster file (

Figure 2A) with the same resolution was integrated into the model generation (INEGI, 2023). Moreover, Mexico’s ecoregions at level IV (CONABIO, 2020) served as the geographic boundary for the model. These ecoregions share similar ecological and biogeographic characteristics, including various vegetation types that may influence the distribution of

C. stejnegeri (Bakx et al., 2019). The raster files were cropped according to the ecoregions that intersected with nearby records of the species: Canyons with tropical dry forest of the Sierra Madre Occidental (SMO), Hills with xerophytic scrub and tropical dry forest of Sinaloa, and Mountains with coniferous, oak, and mixed forests (

Figure 2B).

Data analysis and model validation. Initially addressed multicollinearity and selected the most relevant predictors demonstrating a higher contribution to the model, the Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) of all environmental variables were tested (Abdalaal et al., 2019). This analysis was performed with the “sdm” package in R where the VIF index was obtained for each variable. A VIF index >5 is considered a high multicollinearity among the variables, therefore, it is recommended to discard these variables for the generation of the model (Abdalaal et al., 2019). Five bioclimatic variables were obtained with a VIF index <10, Bio9 (3.002), Bio11 (6.500), Bio14 (2.650), Bio15 (6.300) and Bio19 (1.488). However, the variables Bio11 and Bio15 presented a high multicollinearity index (

Table 1) and a positive linear correlation coefficient (0.813).

Following a reassessment of multicollinearity, the variable Bio11 was excluded, but Bio15 (

Table 1) was retained due to its representation of seasonality data. Despite its high multicollinearity, we decided not to exclude this variable because Sinaloa exhibits pronounced seasonality (Serrano et al., 2014), and it contains the majority of C. stejnegeri records. Therefore, it is plausible that this bioclimatic variable plays a role in influencing the species’ distribution. In this second analysis, none of the variables (Bio9, Bio14, Bio15, and Bio19) displayed a significant VIF index (<3), and there was no evidence of a positive linear correlation coefficient ≤0.5 between them.

Utilized MaxEnt v3.4.4 software (Phillips et al., 2006) to generate the SMD due to its efficiency in yielding acceptable results even with limited data (Abdalaal et al., 2019; Da Silva et al., 2020). Automation of linear L, quadratic Q, and P product features was implemented to simplify the response curves for ease of interpretation. To enhance model robustness, we employed a bootstrap-type model fit, randomizing 40% of the test records while using the remaining data for training. A total of 27 replicates were generated, corresponding to the number of records of C. stejnegeri, with a maximum of 5000 iterations (Dai et al., 2022). The test of equality between sensitivity and specificity served as the threshold rule. Furthermore, the jackknife test, recognized as the best index for small sample sizes (Phillips et al., 2006), was employed to evaluate the percentage contribution of each variable.

To assess the accuracy of the resulting models, we calculated the area under the curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC). The AUC score stands out as a key metric for measuring model performance, primarily due to its independence from the choice of thresholds (Abdalaal et al., 2019; Dai et al., 2022). A higher AUC value, closer to 1, indicates superior model performance (Phillips et al., 2006). The AUC plot is generated by plotting true positive predictions (sensitivity) against false positive predictions (1-specificity) (Fielding and Bell, 1997).

Finally, the output from MaxEnt was in logistic format, representing a habitat suitability map for the species with values ranging from 0 (unsuitable) to 1 (optimal). For additional analysis, the MaxEnt results were imported into QGIS 3.34.3, where three classes of potential habitats were defined: low potential (0-0.30), moderate potential (0.31-0.69), and high potential (≥0.77-1).

Results and Discussion

The MaxEnt model with the average value of the replicates showed an AUC of 0.879, with a standard deviation of 0.065. For this reason, the estimation of the environmental suitability of can be considered to have a good degree of reliability (Phillips et al., 2006).

Figure 3 shows the potential distribution for

C. stejneger. Low probability zones of species presence are represented by blue shades, while reddish colors indicate high habitat suitability, predominantly concentrated in the foothills of the SMO spanning from Sinaloa to the northern part of Nayarit. These regions exhibit high habitat suitability possibly due to the dominance of tropical dry forest (Serrano et al., 2014; Woolrich-Piña et al., 2015), the prevalent vegetation type where the majority of the species’ records have been documented (

Figure 2B; GBIF, 2024). In the state of Durango, elevated levels of habitat suitability for

C. stejnegeri are observed in the SMO, particularly in the municipalities of Tamazula and Otáez, adjacent to the municipality of Cosalá in Sinaloa. This heightened suitability may be attributed to the proximity of these Durango municipalities to Cosalá in Sinaloa, where a significant number of

C. stejnegeri records have been documented.

In the same region, particularly in the municipality of San Dimas in Durango, a small area with high habitat suitability for

C. stejnegeri is depicted in

Figure 3. This observation aligns with Robert Meidinger’s comment (in Uetz et al., 2023), questioning the altitudinal range of 1780 m asl as being too high for

C. stejnegeri, as evident by the low habitat suitability around Yamiroba in the municipality of San Dimas, Durango (

Figure 2A and 3). On the other hand, Reyes-Velasco et al. (2013) suggested that

C. stejnegeri could also be found in Nayarit, Sonora and Chihuahua, although

Figure 3 shows a high suitability of the habitat for the species in the north of Nayarit and southwest of Sonora, the state of Chihuahua does not present a marked suitability environment for the species. This discrepancy might be attributed to

C. stejnegeri’s neotropical biogeographic affinity, asince northeast Sinaloa may be the northernmost limit for neotropical flora and fauna (Gentry, 1946; Morrone et al., 2017; Castro-Bastidas, 2022; Pío-León et al., 2023; Castro-Bastidas et al., 2024). Furthermore, this could also apply to southwest Sonora, although

Figure 3 shows an area of high suitability, this result is probably due to the fact that this is a transitional region from the Sonoran desert to the dry forests at the foot of the SMO (Bezy et al., 2017; unpublished data, HACB).

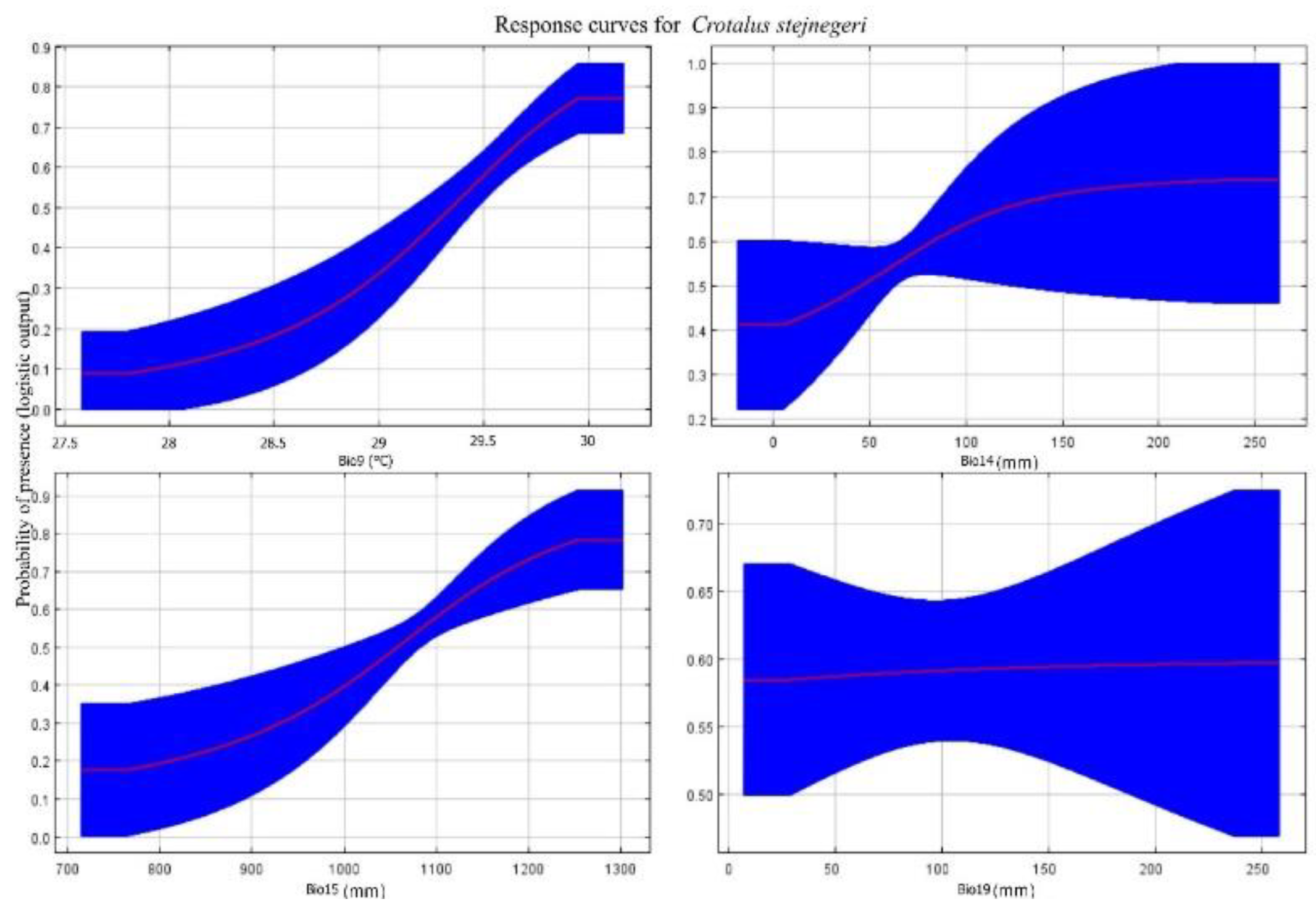

The variables making the most substantial contributions to the habitat suitability model for C. stejnegeri are detailed below: Air temperature during the driest quarter (Bio9) (April, May, and June) stands out as the most influential factor in the model, accounting for a significant 74.5%. This high percentage suggests that alterations in this variable exert a noteworthy impact on the potential distribution of C. stejnegeri. The precipitation seasonality (Bio15) makes a significant contribution, though to a lesser degree compared to the temperature of the driest quarter, representing 15.3% of the model’s influence. This outcome implies that variations in the amount and distribution of precipitation throughout the year play a crucial role in shaping the potential distribution of the species. The amount of reception during the driest month (Bio14) (April) is another relevant factor (9.4%), although its contribution is smaller than the two variables mentioned above. This outcome underscores the significance of water availability during the driest period in the modeling process. The influence of these variables is likely attributed to the fact that most rattlesnakes exhibit heightened activity levels in mid-spring to late summer, corresponding to their reproductive periods (Armstrong and Murphy, 1979; Schuett et al., 2002). This behavior could potentially align with the distribution patterns observed in C. stejnegeri. Moreover, the warm and humid conditions in south-central Sinaloa, attributed to the tropical dry forest of this region (Serrano et al., 2014), could also contribute to shaping the distribution of the species. Conversely, monthly precipitation during the coldest quarter (Bio19) (December, January, and February) makes the smallest contribution to the model at 0.8%, possibly due to variations observed between replicates.

For a more comprehensive analysis,

Figure 4 illustrates the response curves of the variables with the most substantial contributions. According to these curves, C. stejnegeri exhibits a higher probability of occurrence in areas with air temperatures ranging between 29-30°C during the driest quarter (Bio9) (April, May, and June) and precipitation seasonality (Bio15) coefficients between 1000-1200 mm. On the other hand, the species demonstrates probability ranges for occurrence in areas where precipitation during the driest month (Bio14) (April) falls between 25-100 mm. However, there is a low probability of occurrence in areas with monthly precipitation during the coldest quarter (Bio19) (December, January, and February) ranging between 50-150 mm. Notably, this variable exhibits significant variability, evident from the blue standard deviation bands in

Figure 4. This indicates that the relationship between

C. stejnegeri and precipitation during the coldest quarter (Bio19) is less consistent or more variable in specific areas. Therefore, the highlighted variability emphasizes the importance of considering uncertainty in model predictions, potentially indicating areas for future research or improvements in data collection.

Conclusions

The MaxEnt model delivers a reliable estimate of habitat suitability for C. stejnegeri. The potential distribution of the species is prominently observed in the foothills region of the SMO, particularly in the municipalities of Sinaloa and Durango, characterized by a prevalence of tropical dry forest. These results align with previous observations regarding the species’ preference for specific altitudes. The absence of distinct environmental suitability in Chihuahua may be linked to the neotropical biogeographic affinity of the species. Biolimatic variables, notably the temperature of the driest quarter (April, May, and June) and precipitation seasonality, play crucial roles in the modeling, with water availability during the driest month (April) identified as a key factor. However, the variability highlighted by the blue standard deviation bands in the response curves, particularly in precipitation during the coldest quarter (December, January, and February), underscores the necessity of considering uncertainty in model predictions. Additionally, it directs attention to specific areas that warrant further research and efforts to enhance records of the species’ presence.

Acknowledgments

To the curators of the herpetological collection at the Natural History Museum, London for the availability of the photograph of C. stejnegeri (NHMUK: 1883.4.16.64). Also, to Jesús Alberto Loc Barragán for providing information on the alleged records of the species in Nayarit, Mexico.

References

- Abdelaal, M., M. Fois, G. Fenu and G. Bacchetta. 2019. Using MaxEnt modeling to predict the potential distribution of the endemic plant Rosa arabica Crép. in Egypt. Ecological Informatics 50: 68-75. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, BL and JB Murphy. 1979. The natural history of Mexican rattlesnakes. University of Kansas, Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas, Lawrence.

- Bakx, TRM, Z. Koma, AC Seijmonsbergen and WD Kissling. 2019. Use and categorization of Light Detection and Ranging vegetation metrics in avian diversity and species distribution research. Diversity and Distributions 25: 1045-1059. [CrossRef]

- Bezy, RL, PC Rosen, TR Van Devender and EF. Enderson. 2017. Southern distributional limits of the Sonoran Desert herpetofauna along the mainland coast of northwestern Mexico. Mesoamerican Herpetology 4: 138-167.

- Brun, P., NE Zimmermann, C. Hari, L. Pellisier and DN Karger. 2022. Global climate-related predictors at kilometre resolution for the past and future. Earth System Science Data 14: 5573-5603. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Bastidas, HA and JM Serrano. 2022. La plataforma naturalista como herramienta de ciencia ciudadana para documentar la diversidad de anfibios en el estado de Sinaloa, México. Revista Latinoamericana de Herpetología 5: 156-178. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Bastidas, HA. 2022. Nuevos registros del sapo chihuahuense Incilius mccoyi (Anura: Bufonidae) y ampliación de distribución de la rana esmeralda Exerodonta smaragdina (Anura: Hylidae) para Sinaloa, México. Revista Latinoamericana de Herpetología 5: 15-19. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Bastidas, HA, H. Velarde-Urías, JD Jacobo-González and JM Serrano. 2014 The amphibians and reptiles of Sierra Surutato, Sinaloa, Mexico. Sonoran Herpetologist 37.

- CONABIO. 2023. Ecorregiones terrestres de México. http://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/region/ecorregiones.

- Chuine, I. 2010. Why does phenology drive species distribution? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 365: 3149-3160. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, FP, H. Fernandes-Ferreira, MA Montes and LG da Silva. 2020. Distribution modeling applied to deficient data species assessment: A case study with Pithecopus nordestinus (Anura, Phyllomedusidae). Neotropical Biology and Conservation 15: 165-175. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X., W. Wu, L. Ji, S. Tian, B. Yang, B. Guan and D. Wu. 2022. MaxEnt model-based prediction of potential distributions of Parnassia wightiana (Celastraceae) in China. Biodiversity Data Journal 10: e81073. [CrossRef]

- Fielding, HA and JF Bell. 1997. A review of methods for the assessment of prediction error in conservation presence/ausence models. Environment Conservation 24:38-39. [CrossRef]

- Fois, M., A. Cuena-Lombraña, G. Fenu and G. Bacchetta. 2018. Using species distribution models at local scale to guide the search of poorly known species: Review, methodological issues and future directions. Ecological Modelling 385: 124-132. [CrossRef]

- Gaubert, P., G. Veron, M. Colyn, A. Dunham, S. Shul and M. Tranier. 2002. A reassessment of the distributional range of the rare Genetta johnstoni (Viverridae, Carnivora), with some newly discovered specimens. Mammal Review 32: 132-144. [CrossRef]

- GBIF. 2024. GBIF Occurrence Download: Crotalus stejegeri. [CrossRef]

- Gentry, HS. 1946. Notes on the vegetation of Sierra Surotato in northern Sinaloa. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 73: 451-462.

- INEGI. 2023. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/geo2/elevacionesmex/.

- Jacobo-González, JD, DS Chan-Chon, A. Razo-Pérez, A. Leal-Orduño, E. Centenero-Alcalá and RA Lara-Resendiz. 2023. Herpetofauna of the “El mineral de nuestra señora de la candelaria” reserve: a biological treasure in Sinaloa. Revista Latinoamericana de Herpetología 6: e801. [CrossRef]

- Kissling, WD, JA Ahumada, A. Bowser, M. Fernandez, N. Fernández, EA García et al. 2018. Building essential biodiversity variables (EBVs) of species distribution and abundance at a global scale. Biological Reviews 93: 600-625. [CrossRef]

- Meza-Joya, FL, E. Ramos, F. Cediel, V. Martínez-Arias, J. Colmenares and D. Cardona. 2018. Predicted distributions of two poorly known small carnivores in Colombia: the Greater Grison and Striped Hog-nosed Skunk. Mastozoología Neotropical 25: 89-105. [CrossRef]

- Morrone, JJ, T. Escalante and G. Rodríguez-Tapia. 2017. Mexican biogeographic provinces: Map and shapefiles. Zootaxa 4277: 277-279. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, AT and J. Soberón. 2012. Species distribution modeling and ecological niche modeling: getting the concepts right. Natureza and Conservação 10: 102-107. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, SJ, RP Anderson and RE chapire. 2006. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecological Modelling 190: 231-259. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, SJ and M. Dudík. 2008. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 31: 161-175. [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, RL, J. Warnken, ALM Chauvenet and JG Castley 2020. Location biases in ecological research on Australian terrestrial reptiles. Scientific Reports 10: 9691. [CrossRef]

- Pío-León, JF, M. González-Elizondo, R. Vega-Aviña, MS González-Elizondo, JG González-Gallegos, B. Salomón-Montijo, MG Millán-Otero and CA Lim-Vega. 2023. Las plantas vasculares endémicas del estado de Sinaloa, México. Botanical Sciences 101:243-269. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Velasco, J., CI Grünwald, JM Jones and GN Weatherman. 2010. Rediscovery of the rare Autlán longtailed rattlesnake, Crotalus lannomi. Herpetological Review 41: 19-25.

- Reyes-Velasco, J., JM Meik, EN Smith and TA Castoe. 2013. Phylogenetic relationships of the enigmatic longtailed rattlesnakes (Crotalus ericsmithi, C. lannomi, and C. stejnegeri). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 69: 524-534. [CrossRef]

- Schuett, GW, SL Carlisle, AT Holycross, JK O’Leile, DL Hardy, EA van Kirk and WJ Murdoch. 2002. Mating system of male Mojave rattlesnakes (Crotalus scutulatus): seasonal timing of mating, agonistic behavior, spermatogenesis, sexual segment of the kidney, and plasma sex steroids, pp. 515-532. In: GW Schuett, M. Höggren, ME Douglas and HW Greene (eds.), Biology of the vipers. Eagle Mountain Publishing. USA.

- Serrano, JM, CA Berlanga-Robles and A. Ruiz-Luna. 2014. High amphibian diversity related to unexpected values in a biogeographic transitional area in north-western Mexico. Contributions to Zoology 83: 151-166. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasulu, A., B. Srinivasulu and C. Srinivasulu. 2021. Ecological niche modelling for the conservation of endemic threatened squamates (lizards and snakes) in the Western Ghats. Global Ecology and Conservation 28: e01700. [CrossRef]

- Uetz, P., P. Freed, R. Aguilar, F. Reyes and J. Hošek (eds.). 2023. The Reptile Database. http://www.reptile-database.org.

- Van der Heiden, AM and OA Flores-Villela. 2013. New records of the rare Sinaloan Long-tailed Rattlesnake, Crotalus stejnegeri, from southern Sinaloa, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 84: 1343-1348. [CrossRef]

- Van der Heiden, AM. 2019. Crotalus stejnegeri (Sinaloan Long-tailed Rattlesnake). Reproduction in captivity. Herpetological Review 50: 742-743.

- Van der Heiden, A.M. 2021. Crotalus stejnegeri (Sinaloan Long-tailed Rattlesnake). Arboreal behavior. Herpetological Review 52: 868-869.

- Warren, DL and SN Seifert. 2011. Ecological niche modeling in Maxent: the importance of model complexity and the performance of model selection criteria. Ecological Applications 21: 335-342. [CrossRef]

- Woolrich-Piña, GA, P. Ponce-Campos, JA Loc-Barragán, JP Ramírez-Silva, V. Mata-Silva, JD Johnson, E. García-Padilla and LD Wilson. 2016. The herpetofauna of Nayarit, Mexico: composition, distribution, and conservation. Mesoamerican Herpetology 3: 376-448.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).