Submitted:

07 February 2024

Posted:

07 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design, Database, and Population

2.2. Definitions and Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. RESULTS

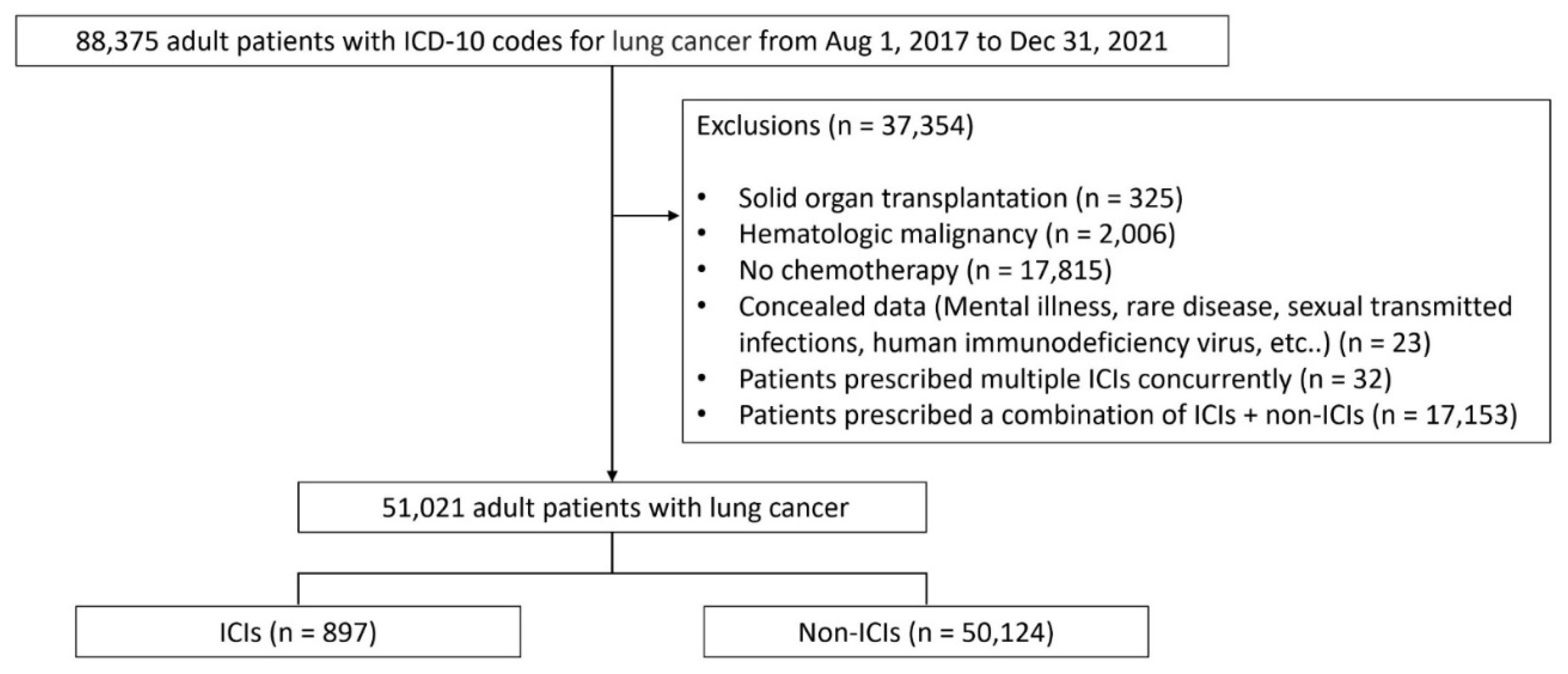

3.1. Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Incidence Rate and Standardized Incidence Ratio of HZ in the ICIs and Non-ICIs Groups

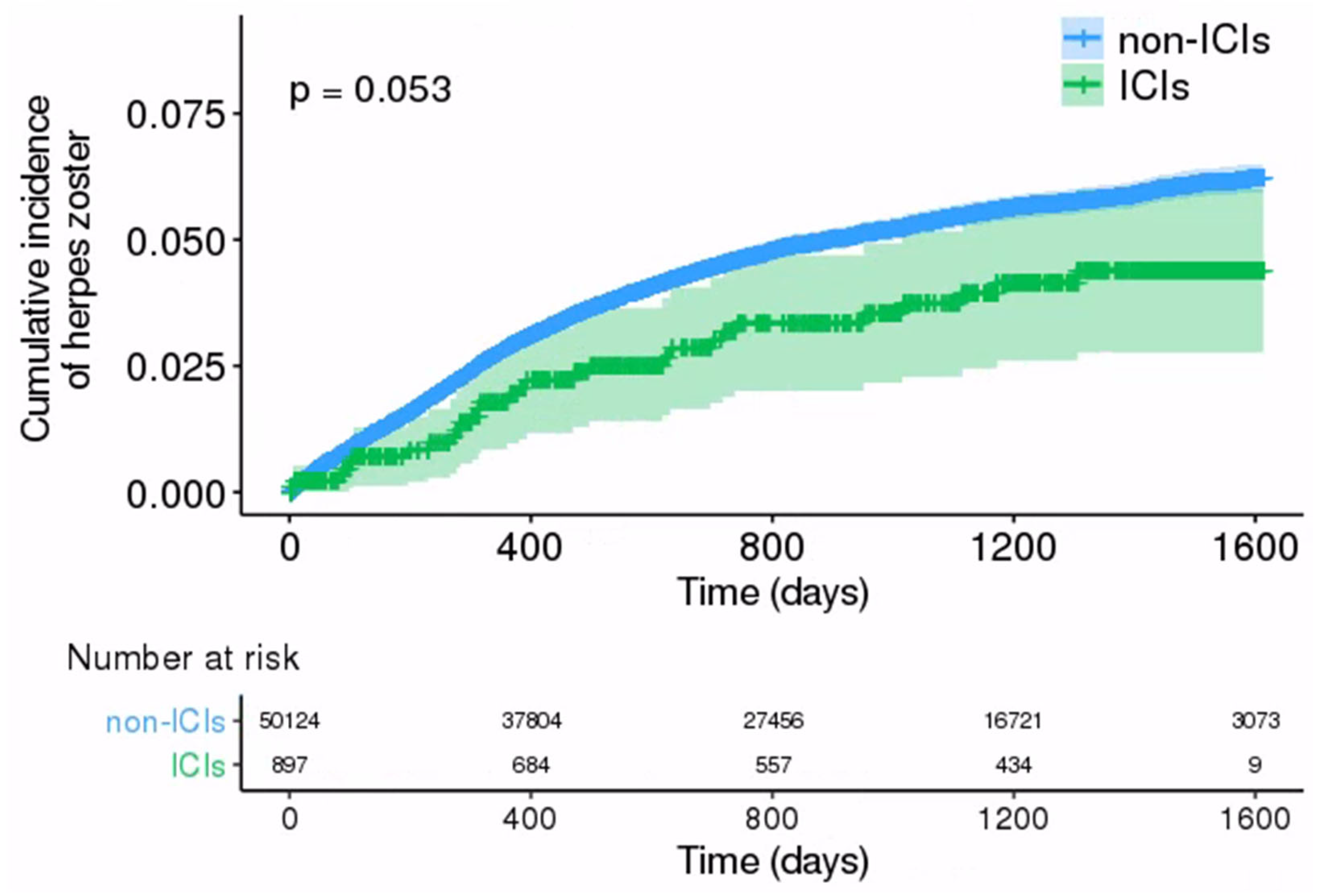

3.3. Comparison of HZ Incidence between ICIs and Non-ICIs Groups

3.4. Risk Factors for Development of HZ in Patients with Lung Cancer

4. DISCUSSION

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Consent for publication

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen JI. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 2013, 369, 1766–7. [CrossRef]

- Gershon AA, Gershon MD, Breuer J, Levin MJ, Oaklander AL, Griffiths PD. Advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis and epidemiology of herpes zoster. J Clin Virol. 2010, 48 (Suppl 1), S2–7. [CrossRef]

- Oxman MN. Immunization to reduce the frequency and severity of herpes zoster and its complications. Neurology. 1995, 45 (Suppl 8), S41–6. [CrossRef]

- Arvin AM, Moffat JF, Redman R. Varicella-zoster virus: aspects of pathogenesis and host response to natural infection and varicella vaccine. Adv Virus Res. 1996, 46, 263–309. [CrossRef]

- Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, Platt R. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1995, 155, 1605–9.

- McKay SL, Guo A, Pergam SA, Dooling K. Herpes Zoster Risk in Immunocompromised Adults in the United States: A Systematic Review. Clin Infect Dis. 2020, 71, e125–e134. [CrossRef]

- Lin YH, Huang LM, Chang IS, et al. Disease burden and epidemiology of herpes zoster in pre-vaccine Taiwan. Vaccine. 2010, 28, 1217–20. [CrossRef]

- 8. Yenikomshian MA, Guignard AP, Haguinet F, et al. The epidemiology of herpes zoster and its complications in Medicare cancer patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2015, 15, 106. [CrossRef]

- Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018, 359, 1350–1355. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dine J, Gordon R, Shames Y, Kasler MK, Barton-Burke M. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: An Innovation in Immunotherapy for the Treatment and Management of Patients with Cancer. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2017, 4, 127–135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe Y, Kikuchi R, Iwai Y, et al. Varicella zoster virus encephalitis mimicking nivolumab-induced autoimmune neuropathy in a patient with lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2019, 14, e163–e165. [CrossRef]

- Sakoh T, Kanzaki M, Miyamoto A, et al. Ramsay-Hunt syndrome and subsequent sensory neuropathy as potential immune-related adverse events of nivolumab: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2019, 19, 1220. [CrossRef]

- Gozzi E, Rossi L, Angelini F, et al. Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis in metastatic lung cancer treated with nivolumab: A case report. Thorac Cancer. 2020, 11, 1330–1333. [CrossRef]

- Taoka M, Ochi N, Yamane H, et al. Herpes zoster in lung cancer patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Transl Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 456–462. [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo M, Romero FA, Argüello E, Kyi C, Postow MA, Redelman-Sidi G. The spectrum of serious infections among patients receiving immune checkpoint blockade for the treatment of melanoma. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2016, 63, 1490–1493. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita K, Terashima T, Mio T. Anti-PD1 Antibody Treatment and the Development of Acute Pulmonary Tuberculosis. J Thorac Oncol. 2016, 11, 2238–2240. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim HR, Keam B, Park YS, et al. Pneumocystis Pneumonia Developing during Treatment of Recurrent Renal Cell Cancer with Nivolumab. The Korean Journal of Medicine. 2018, 93, 571–574. [CrossRef]

- Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012, 366, 2443–54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012, 366, 2455–65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eigentler TK, Hassel JC, Berking C, et al. Diagnosis, monitoring and management of immune-related adverse drug reactions of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016, 45, 7–18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016, 387, 1837–46. [CrossRef]

- Petrelli F, Morelli AM, Luciani A, Ghidini A, Solinas C. Risk of Infection with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Target Oncol. 2021, 16, 553–568. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah NJ, Al-Shbool G, Blackburn M, et al. Safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in cancer patients with HIV, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C viral infection. J Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7, 353. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010, 342, 341–57. [CrossRef]

- Abendroth A, Lin I, Slobedman B, Ploegh H, Arvin AM. Varicella-zoster virus retains major histocompatibility complex class I proteins in the Golgi compartment of infected cells. J Virol. 2001, 75, 4878–88. [CrossRef]

- Laing KJ, Ouwendijk WJD, Koelle DM, Verjans G. Immunobiology of Varicella-Zoster Virus Infection. J Infect Dis. 2018, 218 (suppl_2), S68–S74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zangeneh Z, Golmoghaddam H, Emad M, Erfani N, Doroudchi M. Elevated PD-1 expression and decreased telomerase activity in memory T cells of patients with symptomatic Herpes Zoster infection. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2014, 60, 13–21.

- Channappanavar R, Twardy BS, Suvas S. Blocking of PDL-1 interaction enhances primary and secondary CD8 T cell response to herpes simplex virus-1 infection. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e39757. [CrossRef]

- Hamashima R, Uchino J, Morimoto Y, et al. Association of immune checkpoint inhibitors with respiratory infections: A review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020, 90, 102109. [CrossRef]

- Delanoy N, Michot JM, Comont T, et al. Haematological immune-related adverse events induced by anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy: a descriptive observational study. Lancet Haematol. 2019, 6, e48–e57. [CrossRef]

- Anastasopoulou A, Ziogas DC, Samarkos M, Kirkwood JM, Gogas H. Reactivation of tuberculosis in cancer patients following administration of immune checkpoint inhibitors: current evidence and clinical practice recommendations. J Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7, 239. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe Y, Kikuchi R, Iwai Y, et al. Varicella Zoster Virus Encephalitis Mimicking Nivolumab-Induced Autoimmune Neuropathy in a Patient with Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019, 14, e163–e165. [CrossRef]

- Lasagna A, Arlunno B, Imarisio I. A case report of pulmonary nocardiosis during pembrolizumab: the emerging challenge of the infections on immunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2022, 14, 1369–1375. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar-Molnar E, Chen B, Sweeney KA, et al. Programmed death-1 (PD-1)-deficient mice are extraordinarily sensitive to tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107, 13402–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousif S, Singh Y, Prasad DV, Sharma P, Van Kaer L, Das G. T cells from Programmed Death-1 deficient mice respond poorly to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e19864. [CrossRef]

- Sakai S, Kauffman KD, Sallin MA, et al. CD4 T Cell-Derived IFN-gamma Plays a Minimal Role in Control of Pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection and Must Be Actively Repressed by PD-1 to Prevent Lethal Disease. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005667. [CrossRef]

- Price P, Murdoch DM, Agarwal U, Lewin SR, Elliott JH, French MA. Immune restoration diseases reflect diverse immunopathological mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009, 22, 651–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Z, Liu T, Zhang X, et al. Opportunistic infections complicating immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2020, 11, 1689–1694. [CrossRef]

- Thompson JA, Schneider BJ, Brahmer J, et al. Management of Immunotherapy-Related Toxicities, Version 1.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019, 17, 255–289. [CrossRef]

| ICIs | Non-ICIs (n = 50,124) |

p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atezolizumab (n = 126) |

Durvalumab (n = 2) |

Nivolumab (n = 309) |

Pembrolizumab (n = 460) |

Total (n = 897) |

|||

| Age (year), n (%) | 0.008 | ||||||

| < 40 (%) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (0.9) | 6 (0.7) | 475 (0.9) | |

| 40–50 (%) | 10 (7.9) | 0 (0) | 18 (5.8) | 16 (3.5) | 44 (4.9) | 2,019 (4.0) | |

| 50–60 (%) | 22 (17.5) | 0 (0) | 55 (17.8) | 79 (17.2) | 156 (17.4) | 8,040 (16.0) | |

| 60–70 (%) | 42 (33.3) | 2 (100) | 116 (37.5) | 143 (31.1) | 303 (33.8) | 18,395 (36.7) | |

| 70–80 (%) | 43 (34.1) | 0 (0) | 96 (31.1) | 159 (34.6) | 298 (33.2) | 17,555 (35.0) | |

| ≥ 80 (%) | 8 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 23 (7.4) | 59 (12.8) | 90 (10.0) | 3,640 (7.3) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.3112 | ||||||

| Male | 89 (70.6) | 2 (100) | 253 (81.9) | 334 (72.6) | 678 (75.6) | 37,109 (74.0) | |

| Female | 37 (29.4) | 0 (0) | 56 (18.1) | 126 (27.4) | 219 (24.4) | 13,015 (26.0) | |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||||||

| Diabetes | 51 (40.5) | 0 (0) | 106 (34.3) | 193 (42.0) | 350 (39.0) | 21,708 (43.3) | 0.011 |

| Cardiovascular disease* | 51 (40.5) | 0 (0) | 81 (26.2) | 169 (36.7) | 301 (33.6) | 20,791 (41.5) | <0.001 |

| Chronic lung diseases | 94 (74.6) | 1 (50) | 199 (64.4) | 307 (66.7) | 601 (67.0) | 36,234 (72.3) | 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney diseases | 12 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 18 (5.8) | 29 (6.3) | 59 (6.6) | 2,751 (5.5) | 0.179 |

| Chronic liver diseases | 6 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 10 (3.2) | 9 (2.0) | 25 (2.8) | 1,404 (2.8) | 1.000 |

| Rheumatic diseases | 9 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.3) | 32 (7.0) | 48 (5.4) | 3,221(6.4) | 0.217 |

|

Concomitant use of immunosuppressive drugs, n (%) |

|||||||

| Immunosuppressant | 10 (7.9) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.9) | 15 (3.3) | 31 (3.5) | 2,428 (4.8) | 0.065 |

| Steroid** | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 12 (3.9) | 18 (3.9) | 34 (3.8) | 3,386 (6.8) | 0.001 |

| ICIs | Non-ICIs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event (n) | Person-years | Incidence* (95% CI) | Event (n) | Person-years | Incidence* (95% CI) | |

| Total | 29 | 2,395.45 | 1,210.63 (844.97–1689.36) | 2,233 | 119,537.78 | 1,868.03 (1791.34–1945.44) |

| Age, n (%) | ||||||

| < 40 | 0 | 13.92 | 0 (0–0) | 19 | 1,166.73 | 1,628.48 (1047.07–2438.24) |

| 40–49 | 0 | 131.22 | 0 (0–0) | 74 | 5,042.06 | 1,467.65 (1170.00–1820.42) |

| 50–59 | 4 | 446.80 | 895.25 (363.36–1962.22) | 410 | 20,084.68 | 2,041.36 (1853.26–2243.62) |

| 60–69 | 11 | 849.69 | 1,294.60 (729.75–2164.36) | 921 | 43,870.17 | 2,099.38 (1968.17–2237.11) |

| 70–79 | 12 | 784.60 | 1,529.44 (882.22–2508.54) | 716 | 41,251.46 | 1,735.70 (1610.87–1862.60) |

| ≥ 80 | 2 | 169.22 | 1,181.90 (365.61–3292.58) | 93 | 8,122.67 | 1,144.94 (935.18–1389.07) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 23 | 1,810.25 | 1,270.54 (849.45–1839.98) | 1,471 | 89,520.82 | 1,643.19 (1561.37–1728.22) |

| Female | 6 | 585.20 | 1,025.29 (480.92–1993.90) | 762 | 30,016.96 | 2,538.56 (2364.71–2721.94) |

| ICIs | Non-ICIs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed event (n) | Expected event (n) | SIR (95% CI) | p-value | Observed event (n) | Expected event (n) | SIR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Male | ||||||||

| < 40 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 (0–0) | 1.00 | 11 | 0.36 | 30.22 (16.74–54.57) | < 0.01 |

| 40–49 | 0 | 0.10 | 0 (0–0) | 1.00 | 37 | 3.16 | 11.69 (8.47–16.13) | < 0.01 |

| 50–59 | 2 | 0.47 | 4.26 (1.07–17.05) | 0.04 | 224 | 21.01 | 10.66 (9.35–12.15) | < 0.01 |

| 60–69 | 18 | 1.49 | 5.37 (2.69–10.75) | < 0.01 | 609 | 78.64 | 7.74 (7.15–8.38) | < 0.01 |

| 70–79 | 11 | 1.91 | 5.75 (3.19–10.39) | < 0.01 | 521 | 98.19 | 5.32 (4.88–5.79) | < 0.01 |

| ≥ 80 | 2 | 1.98 | 1.01 (0.25–4.04) | 0.99 | 68 | 88.02 | 0.77 (0.61–0.98) | 0.03 |

| Female | ||||||||

| < 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 1.00 | 8 | 0.41 | 19.45 (9.73–38.90) | < 0.01 |

| 40–49 | 0 | 0.08 | 0 (0–0) | 1.00 | 37 | 4.12 | 8.99 (6.51–12.40) | < 0.01 |

| 50–59 | 2 | 0.43 | 4.68 (1.17–18.72) | 0.03 | 186 | 19.34 | 9.62 (8.33–11.10) | < 0.01 |

| 60–69 | 3 | 0.75 | 3.99 (1.29–12.37) | 0.02 | 312 | 36.09 | 8.65 (7.74–9.66) | < 0.01 |

| 70–79 | 1 | 0.51 | 1.96 (0.28–13.9) | 0.50 | 194 | 29.60 | 6.55 (5.69–7.54) | < 0.01 |

| ≥ 80 | 0 | 0.43 | 0 (0–0) | 1.00 | 25 | 27.43 | 0.91 (0.62–1.35) | 0.64 |

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Total | 0.70 (0.48–1.01) | 0.05 | 0.69 (0.48–1.00) | 0.05 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.84 (0.55–1.26) | 0.39 | 0.84 (0.55–1.26) | 0.40 |

| Female | 0.43 (0.19–0.96) | 0.04 | 0.42 (0.19–0.94) | 0.04 |

| Age | ||||

| < 68 years | 0.59 (0.35–0.99) | 0.05 | 0.58 (0.34–0.99) | 0.05 |

| ≥ 68 years | 0.84 (0.51–1.40) | 0.51 | 0.84 (0.50–1.40) | 0.50 |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 0.81 (0.53–1.23) | 0.32 | 0.84 (0.55–1.28) | 0.41 |

| Yes | 0.49 (0.23–1.03) | 0.06 | 0.48 (0.23–1.01) | 0.05 |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||

| No | 0.65 (0.42–1.01) | 0.06 | 0.65 (0.41–1.01) | 0.05 |

| Yes | 0.80 (0.42–1.55) | 0.52 | 0.85 (0.44–1.64) | 0.63 |

| Chronic lung diseases | ||||

| No | 0.59 (0.32–1.11) | 0.10 | 0.58 (0.31–1.09) | 0.09 |

| Yes | 0.76 (0.48–1.19) | 0.23 | 0.76 (0.48–1.20) | 0.24 |

| Chronic kidney diseases | ||||

| No | 0.71 (0.49–1.03) | 0.07 | 0.70 (0.48–1.02) | 0.07 |

| Yes | 0.52 (0.07–3.74) | 0.52 | 0.52 (0.07–3.89) | 0.53 |

| Chronic liver diseases | ||||

| No | 0.68 (0.47–0.99) | 0.05 | 0.68 (0.47–0.99) | 0.05 |

| Yes | 1.57 (0.22–11.41) | 0.65 | 1.18 (0.13–10.91) | 0.88 |

| Rheumatic diseases | ||||

| No | 0.66 (0.45–0.97) | 0.03 | 0.65 (0.44–0.97) | 0.03 |

| Yes | 1.52 (0.48–4.78) | 0.47 | 1.76 (0.52–5.93) | 0.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).