Submitted:

06 February 2024

Posted:

07 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

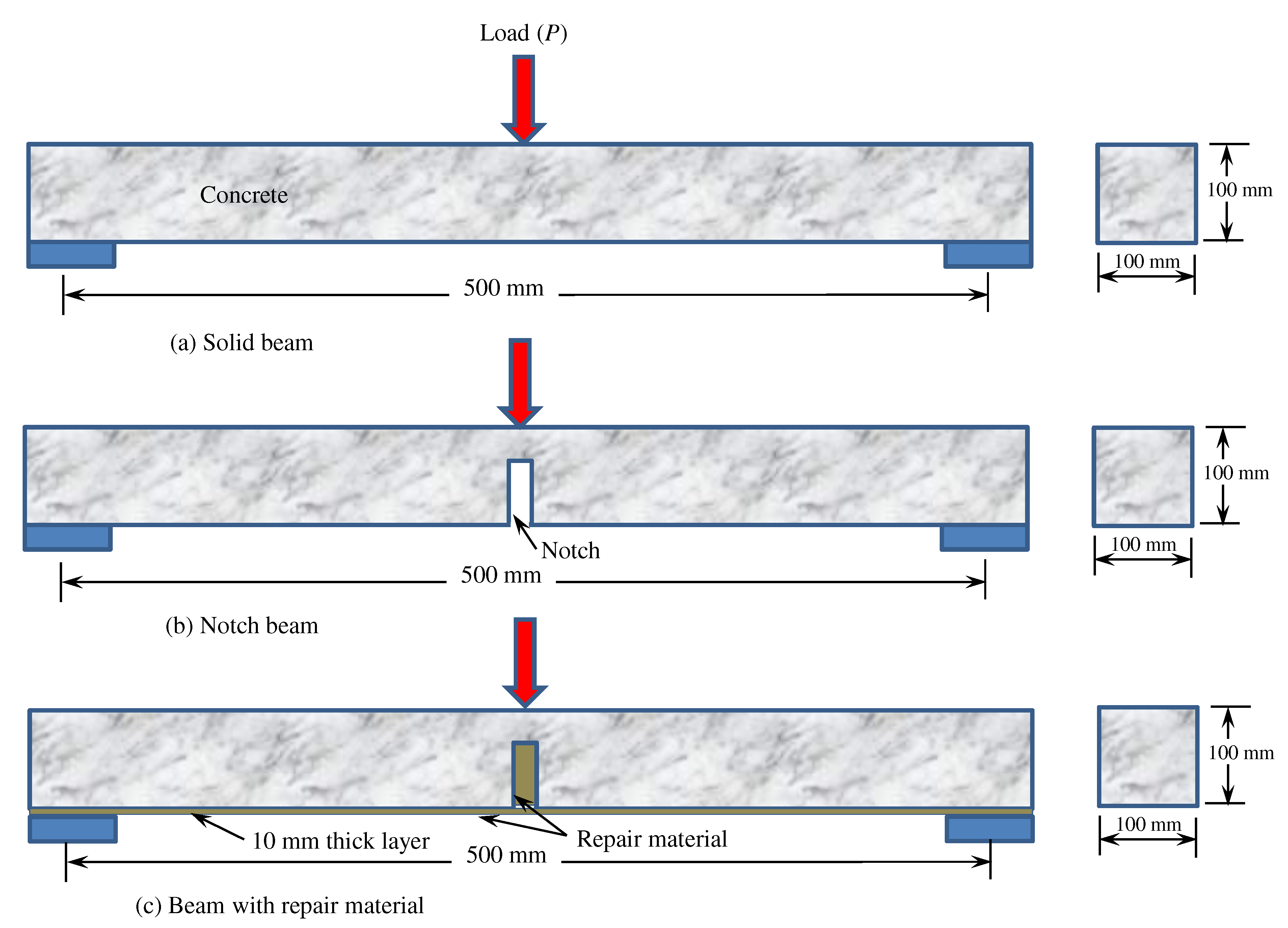

2. Experimental study

3. Numerical study

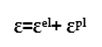

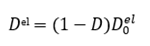

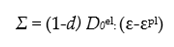

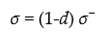

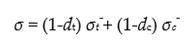

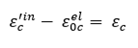

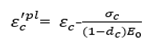

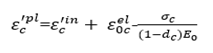

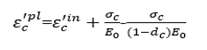

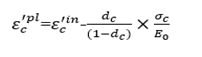

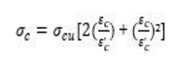

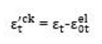

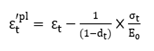

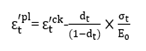

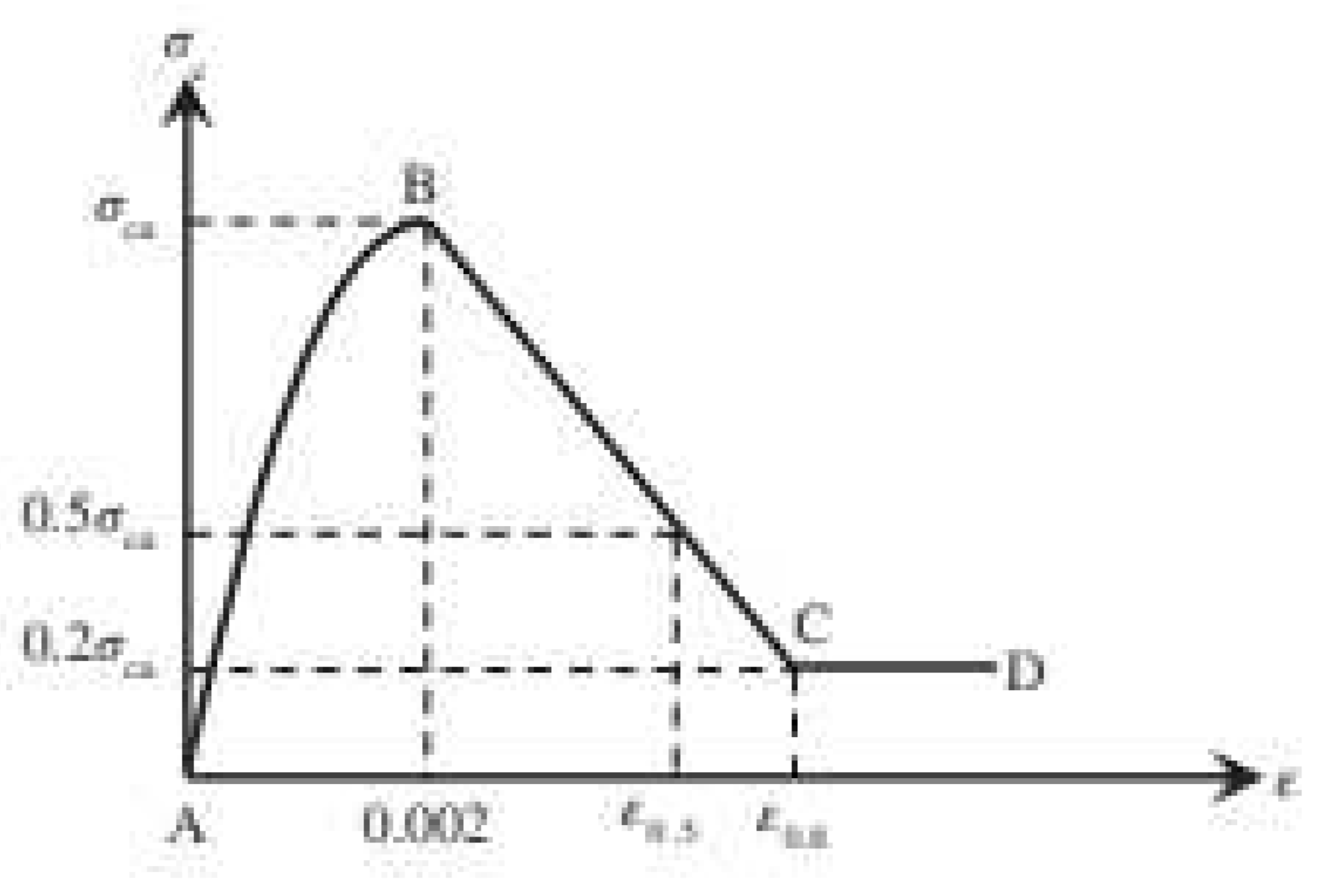

define in Figure 5

define in Figure 5

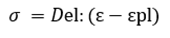

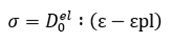

as shown in Figure 5

as shown in Figure 5

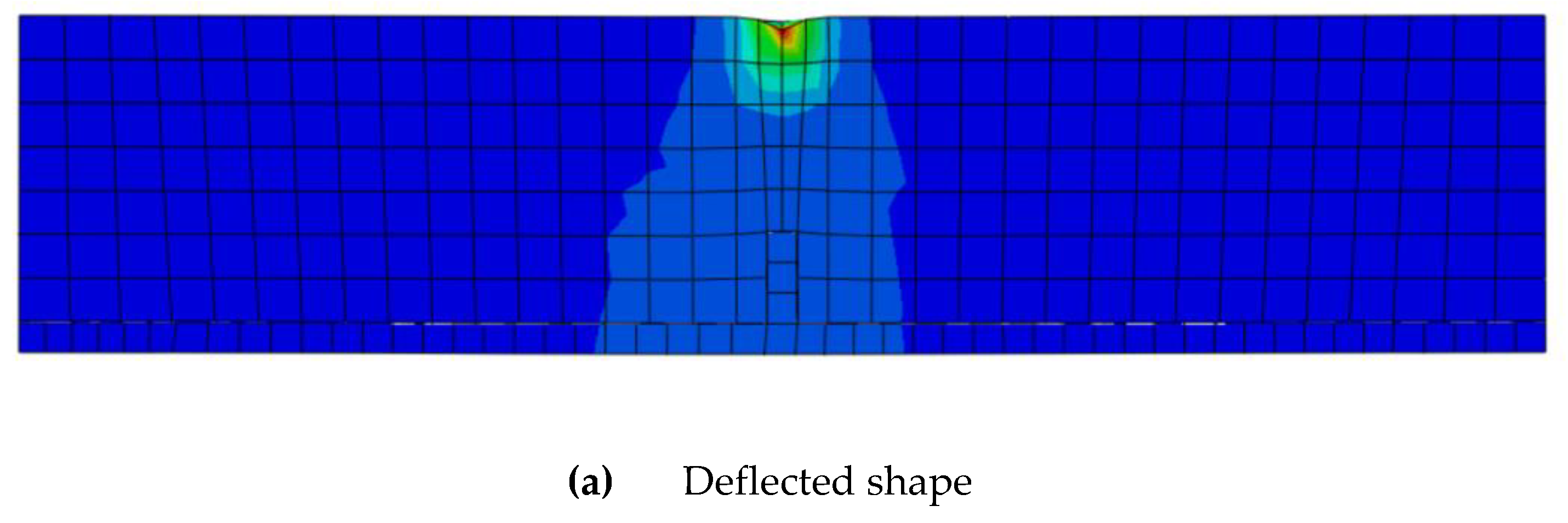

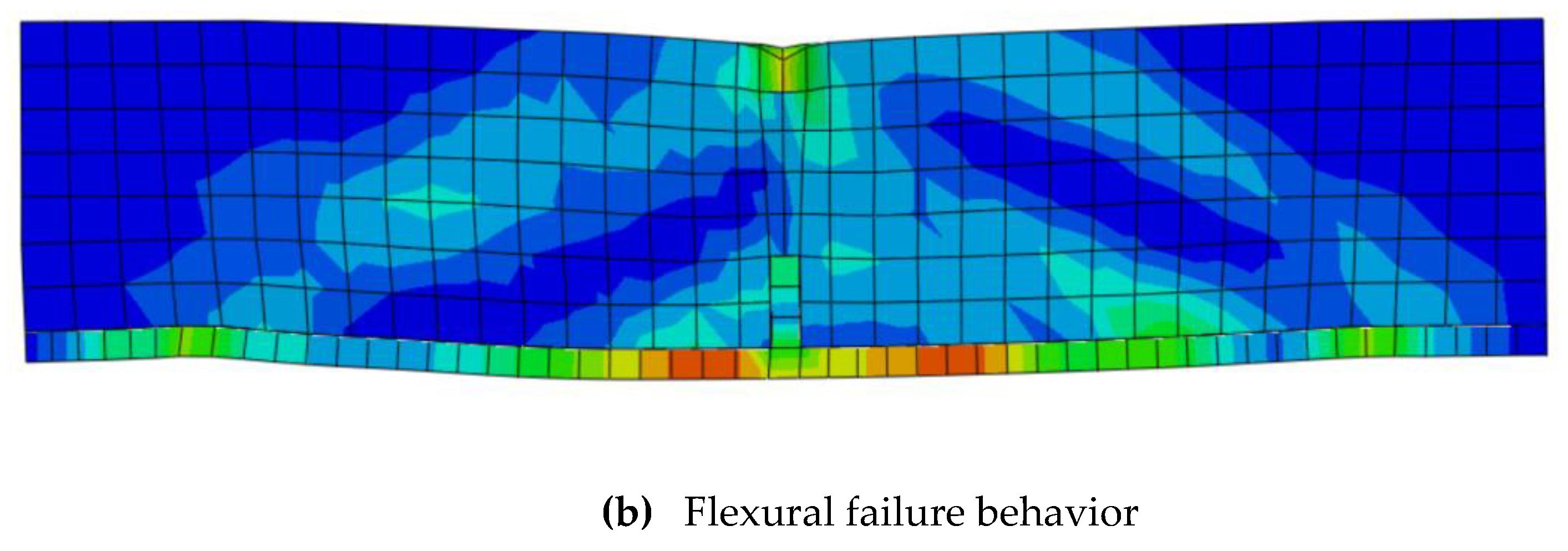

3.1. Validation of the numerical model

3.2. Present Numerical Study

4. Results and Discussions

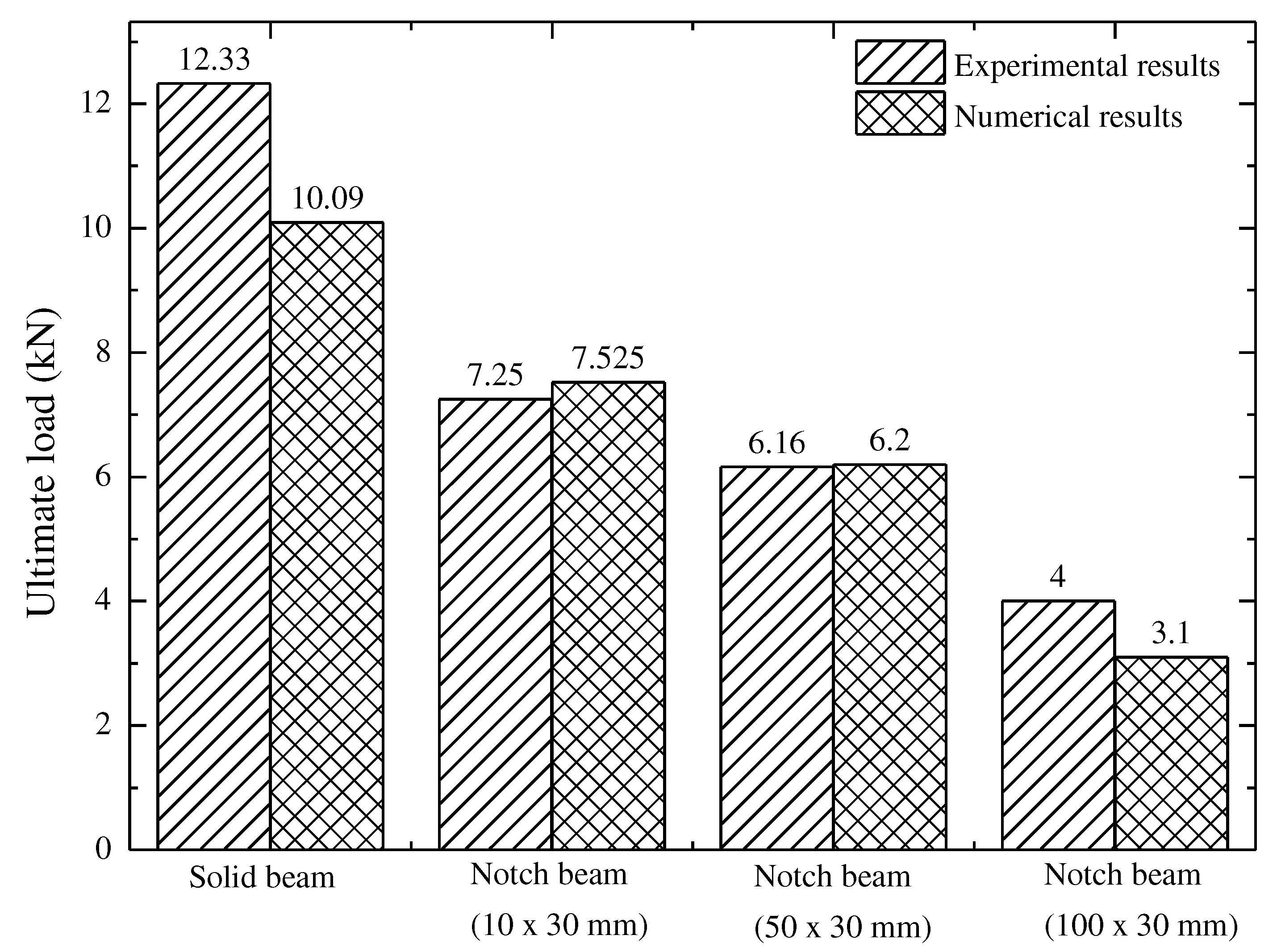

4.1. Effect of notch

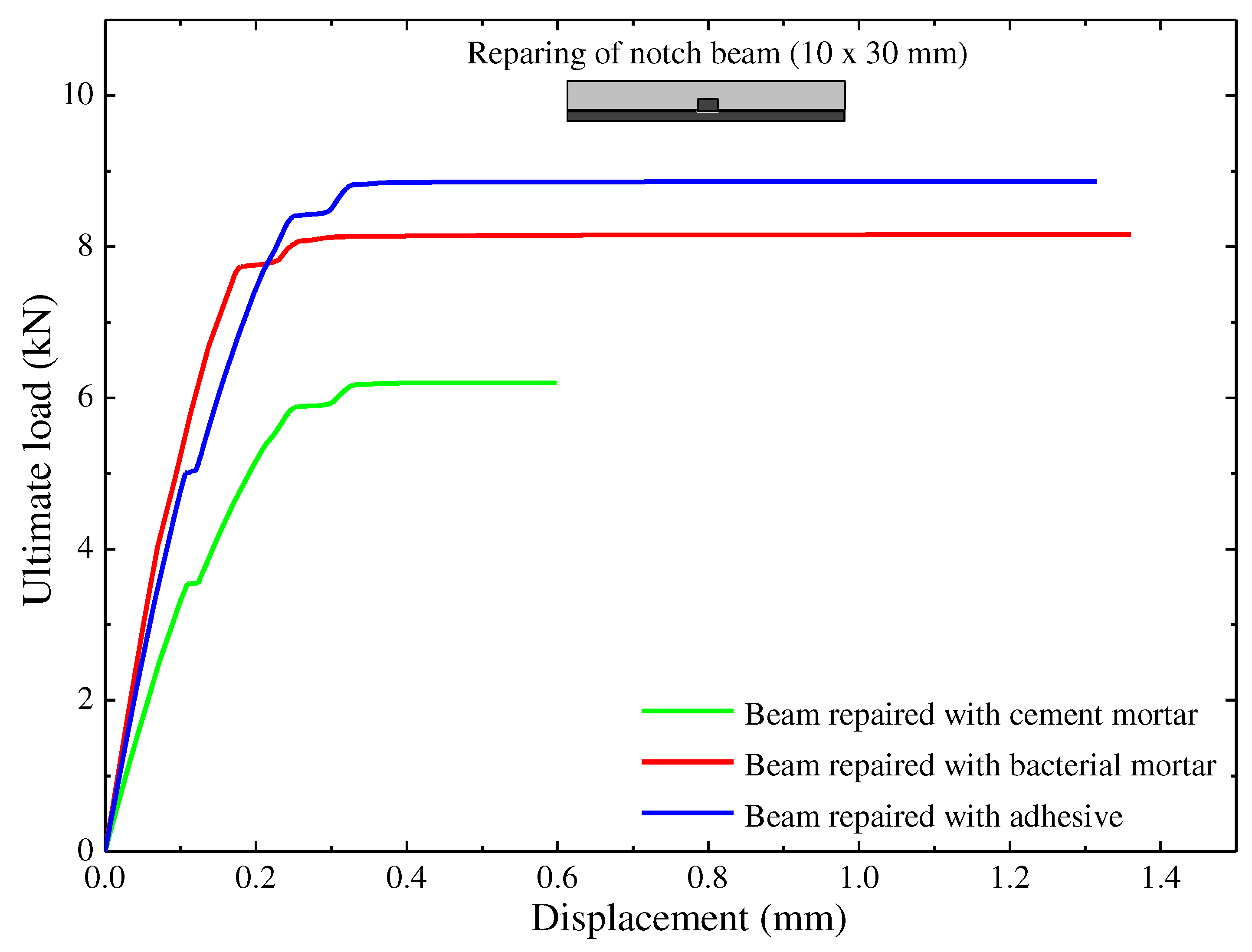

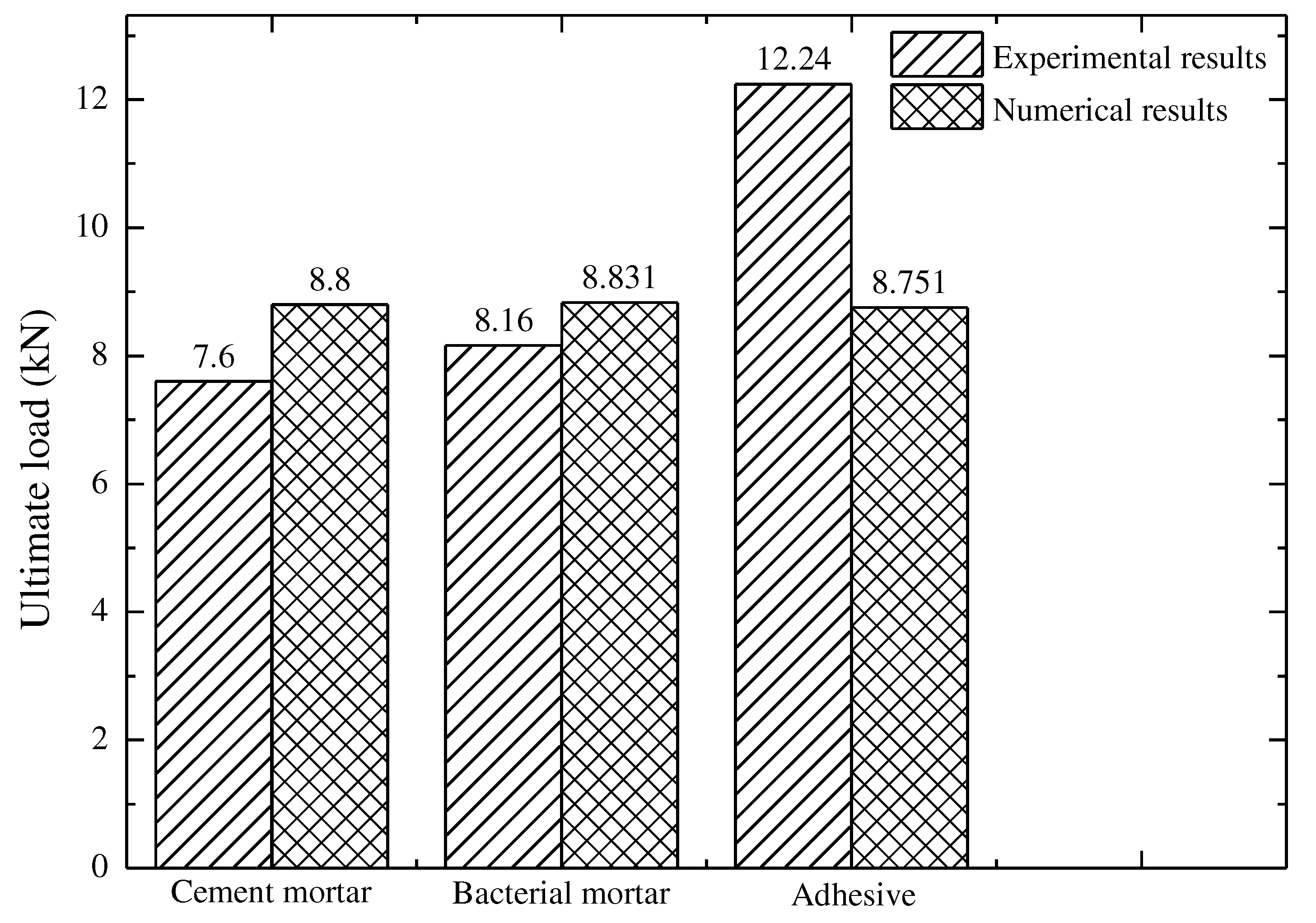

4.2. Effect of repairing materials

5. Conclusions

- There is an excellent correlation between the experimental and finite element numerical results at every loading stage to failure to predicate the flexural behavior of the concrete beam. Also the FE numerical platform can overcome the drawback of experimental testing.

- The differences in numerical and experimental measured results ranges from 0.65 - 22.20 % for the ultimate load carrying capacity.

- As the notch size increases the ultimate load carrying capacity of beam was reduced. The notch volume from 0.6% - 6% for which the percentage reduction in load carrying capacity was observed to be in a range of 41.20% - 67.56%.

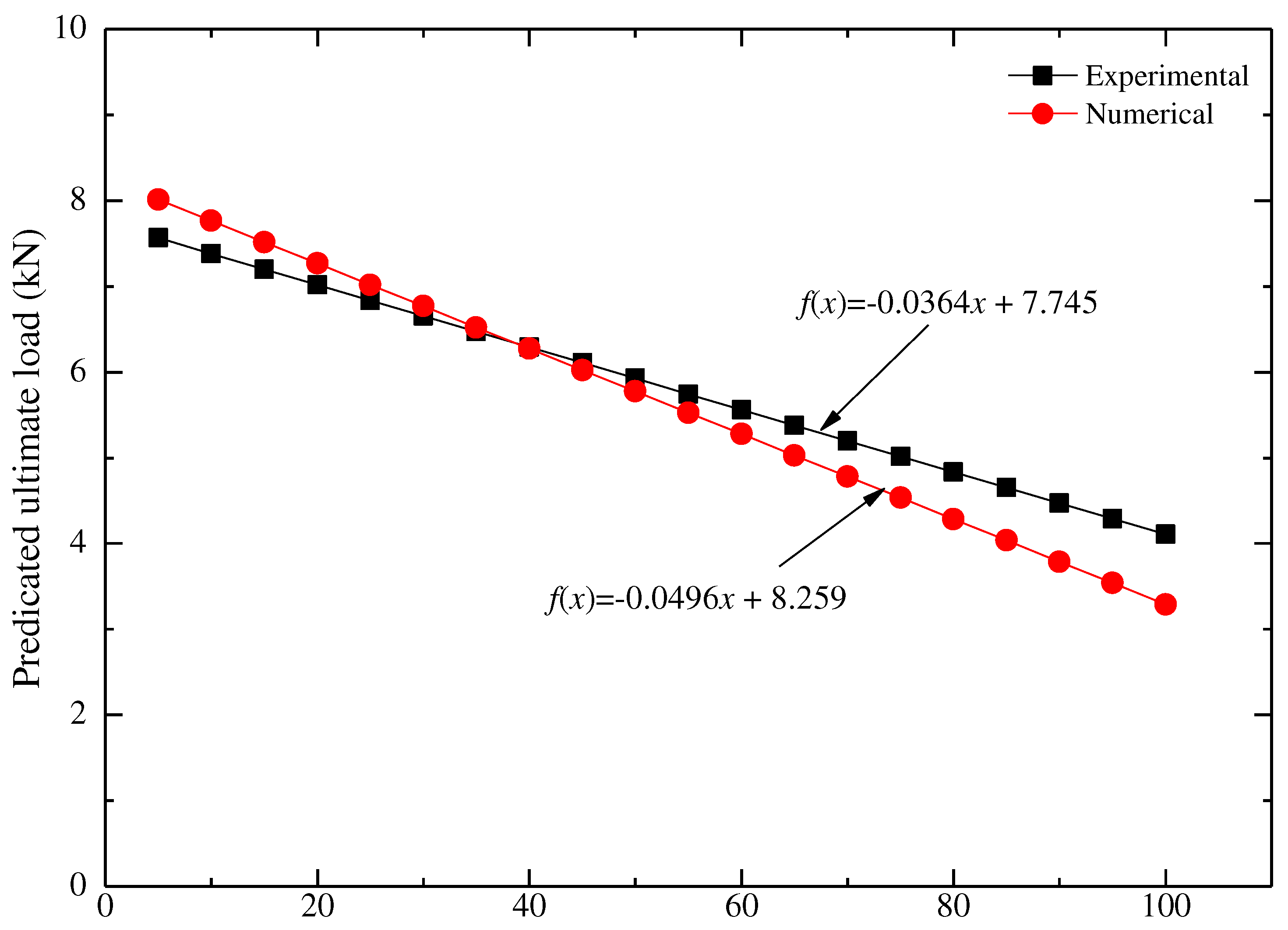

- A linear regression (LR) model is proposed to predict the ultimate load values at an interval of 5 mm notch width up to maximum width of notch 100 mm. It can be observed that the ultimate load capacity for repaired beam is increased as compared to the notch beam for all the three repairing materials under consideration.

- It can be seen that the correlation coefficient R2 with experimental and numerical results shows a difference of nearly 1.12%. The root mean square errors (RMSE) for experimental and numerical results are 0.288 and 0.522, respectively.

- The maximum ultimate load was increased in case of notch beam repaired using adhesive. Also the FE numerical platform can be used to simulate the repair materials and can study their performance. As compared to the cement mortar the performance of the bacterial mortar in terms of the ultimate load was more. The bacterial mortar is more sustainable and more durable as a repair material for the concrete structures.

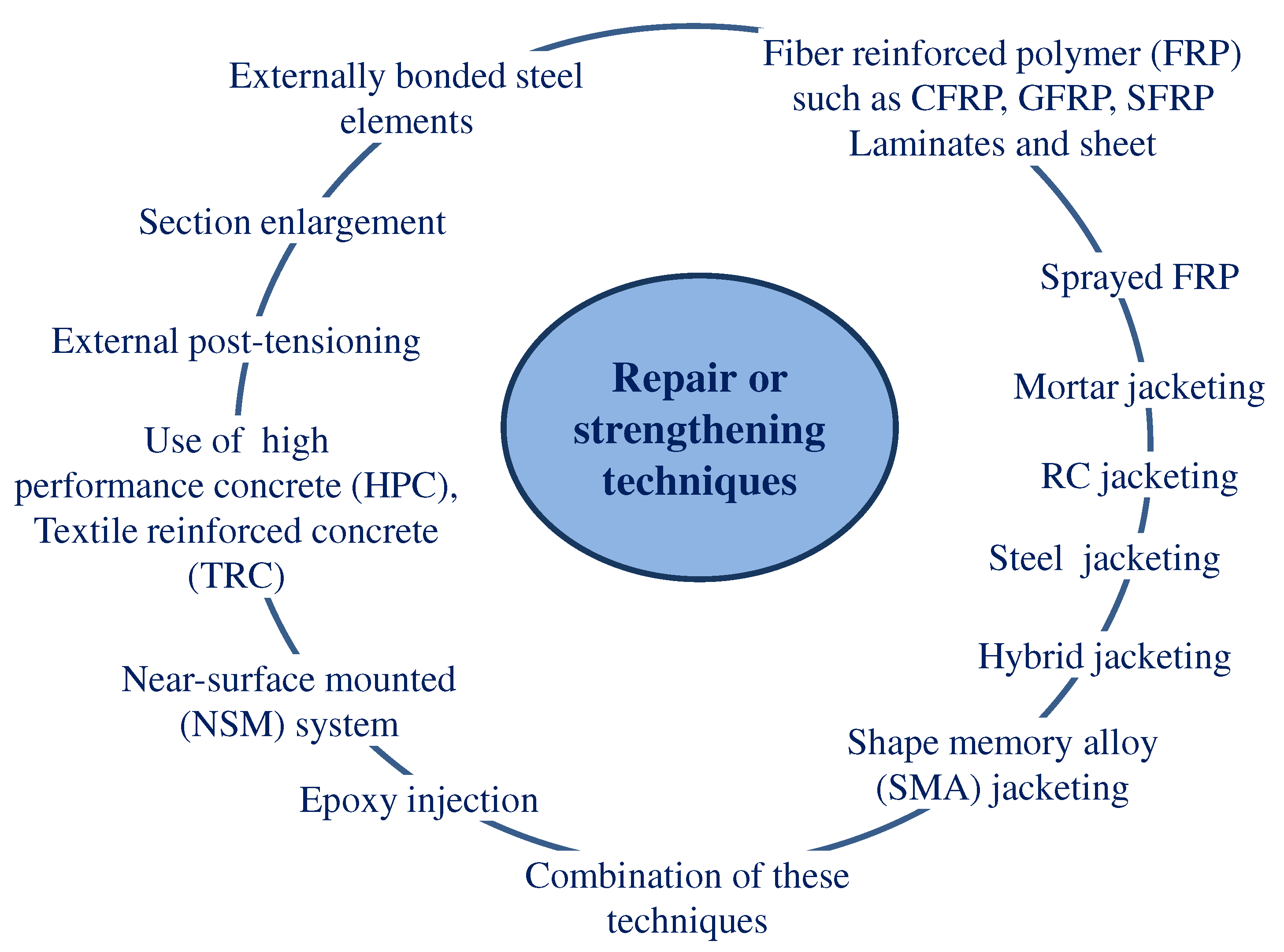

- While selecting any repair and/or strengthening material depends on repair time, localized changes in the stiffness of the member, strength, ductility, durability, cost, and work safety.

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Raza, S.; Khan, M.K.I.; Menegon, S.J.; Tsang, H.H.; Wilson, J.L. Strengthening and repair of reinforced concrete columns by jacketing: State-of-the-art review, Sustainability. 2019, 11, 3208. [CrossRef]

- Obaid, W.A.; AL-asadi, A.K.; Shaia, H. Repair and strengthening of concrete beam materials using different CFRP laminates configuration, Materials Today: Proceedings. 2022, 49(7), 2806-2810,. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.F.; Latief, A.F. Repairing and strengthening techniques of RC beams: A review, 3rd International Conference for Civil Engineering Science (ICCES 2023), IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2023, 1232, 012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinola, G.; Meda, A.; Plizzari, G.A.; Rinaldi, Z. Strengthening and repair of RC beams with fiber reinforced concrete. Cement and Concrete Composites. 2010, 32, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pešić, N.; Pilakoutas, K. Flexural analysis and design of reinforced concrete beams with externally bonded FRP reinforcement, Materials and Structures/ Materiaux et Constructions. 2005, 38, 183–92. [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, A.; Nardone, F.; Iovinella, I.; Ceroni, F.; Pecce, M. Flexural strengthening of concrete beams with EB-FRP, SRP and SRCM: Experimental investigation, Composites Part B: Engineering. 2013, 46, 91–101. [CrossRef]

- Słowik, M. The analysis of failure in concrete and reinforced concrete beams with different reinforcement ratio, Archive of Applied Mechanics. 2019, 89, 885–895. [CrossRef]

- Sharaky, I.A.; Ahmed, S.E.; Alharthi, Y.M. Flexural response and failure analysis of solid and hollow core concrete beams with additional opening at different locations, Materials. 2021, 14(23). [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Ming, Z.; Ansari, F. Failure characteristics of reinforced concrete beams repaired with CFRP composites, Proceedings of the third International Conference on Composites in Infrastructure (ICCI’02). 2002, 51-65.

- Rahim, N.I.; Mohammed, B.S.; Al-Fakih, A.; Wahab, M.M.A.; Liew, M.S.; Anwar, A.; Amran, Y.H.M. Strengthening the structural behavior of web openings in RC deep beam using CFRP, Materials. 2020, 13, 2804. [CrossRef]

- Maraq, M.A.A.; Tayeh, B.A.; Ziara, M.M.; Alyousef, R. Flexural behavior of RC beams strengthened with steel wire mesh and self-compacting concrete jacketing- Experimental investigation and test results, Journal of Materials Research and Technology. 2021, 10, 1002-1019. [CrossRef]

- Chalioris, C.E.; Pourzitidis, C.N. Rehabilitation of shear-damaged reinforced concrete beams using self-compacting concrete jacketing, ISRN Civil Engineering. 2012, 816107. [CrossRef]

- Mostofinejad, D.; Shameli, S.M. Externally bonded reinforcement in grooves (EBRIG) technique to postpone debonding of FRP sheets in strengthened concrete beams, Construction and Building Materials. 2013, 38, 751–58. [CrossRef]

- Sirisonthi, A.; Julphunthong, P.; Joyklad, P.; Suparp, S.; Ali, N.; Javid, M.A.; Chaiyasarn, K.; Hussain, Q. Structural behavior of large-scale hollow section RC beams and strength enhancement using carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites, Polymers. 2022, 14, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, D.; Rojas-Solano, L.B.; Pijaudier-Cabot, G. Failure and size effect for notched and unnotched concrete beams. International Journal for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics. 2013, 37, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, Z.; Rahman, M.M.; Carloni, C. Largest experimental investigation on size effect of concrete notched beams, Journal of Engineering Mechanics ASCE. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.C.S.; Reis, J.M.L. Experimental investigation of mixed-mode-I/II fracture in polymer mortars using digital image correlation method, Latin American Journal of Solids and Structures. 2014, 11(2), 330-343. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Niu, S.; Ding, J. An experimental investigation on the failure behavior of a notched concrete beam strengthened with carbon fiber-reinforced polymer, International Journal of Polymer Science. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadela, M.; Cińcio, A.; Kozlowski, M. Degradation analysis of notched foam concrete beam, Applied Mechanics and Materials. 2015, 797, 96-100. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.A.; Jaini, Z.M.; Rahim, N.A.A.; Razak, S.A.A. An experimental study on the fracture energy of foamed concrete using V-notched beams. In: Hassan, R., Yusoff, M., Alisibramulisi, A., Mohd Amin, N., Ismail, Z. (eds) InCIEC 2014. Springer, Singapore. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Benarbia, D.; Benguediab, M. Propagation of cracks in reinforced concrete beams cracked and repaired by composite materials. Mechanics and Mechanical Engineering. 2017, 21, 591–601. [Google Scholar]

- Lacidogna G. Piana G. ,Accornero F. , Carpinteri A. Experimental investigation on crack growth in prenotched concrete beams. Proceedings 2018, 2, 429. [CrossRef]

- Valdez Aguilar, J.; Juárez-Alvarado, C.A.; Mendoza-Rangel, J.M.; Terán-Torres, B.T. Effect of the notch-to-depth ratio on the post-cracking behavior of steel-fiber-reinforced concrete, Materials. 2021, 14, 445. [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Qian, C.; Li, R. Factors affecting crack repairing capacity of bacteria-based self-healing concrete. Construction and Building Materials. 2015, 87, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunamineni, V.; Murmu, M.; Deo, S.V. Bacteria based self healing concrete- A review, Construction and Building Materials. 2017, 152, 1008–1014. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, C.; Das, B.; Jayabalan, R.; Davis, R.; Sarkar, P. Effect of nonureolytic bacteria on engineering properties of cement mortar, Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, ASCE. 2017. 29, 06016024. [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Beltran, M.G.; Jonkers, H.M.; Schlangen, E. Characterization of sustainable bio-based mortar for concrete repair, Construction and Building Materials. 2014, 67 (Part C), 344-352. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, C.; Das, B.; Jayabalan, R.; Davis, R.; Sarkar, P. Effect of nonureolytic bacteria on engineering properties of cement mortar, Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, ASCE. 2017. 29, 06016024. [CrossRef]

- Kunamineni, V.; Murmu, M. Effect of calcium lactate on compressive strength and self-healing of cracks in microbial concrete, Frontiers of Structural and Civil Engineering. 2019, 13, 515–525. [CrossRef]

- Abo-El-Enein, S.A.; Ali, A.H.; Talkhan, F.N.; Abdel-Gawwad, H.A. Application of microbial bio cementation to improve the physical mechanical properties of cement mortar. HBRC Journal. 2019, 9, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Belie, N. Application of bacteria in concrete: A critical evaluation of the current status, RILEM Technical Letters. 2016, 1, 56–61. [CrossRef]

- Tziviloglou, E.; Wiktor, V.; Jonkers, H.M.; Schlangen, E. Bacteria-based self-healing concrete to increase liquid tightness of cracks, Construction and Building Materials. 2016, 122, 118–125. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Dai, P.S.; Wei, K.H. Autonomous healing in concrete by bio-based healing agents – A review, Construction and Building Materials. 2017, 146, 419–428. [CrossRef]

- Alazhari, M.; Sharma, T.; Heath, A.; Cooper, R.; Paine, K. Application of expanded perlite encapsulated bacteria and growth media for self-healing concrete, Construction and Building Materials. 2018, 160, 610–619. [CrossRef]

- Morsali, S.; Isildar, G.Y.; Zar gari, Z.H.; Tahni, A. The application of bacteria as a main factor in self-healing concrete technology, Journal of Building Pathology and Rehabilitation. 2019, 4, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Priyom, S.N.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, G.M.S.; Islam, M.S.; Rahman, M.A.; Zawad, M.F.S.; Shumi, W. Efficacy of Bacillus Cereus Bacteria in Improving Concrete Properties through Bio-precipitation. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering. 2023, 47, 3309–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IS 10262 (2019), Concrete Mix Proportioning – Guidelines, Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi.

- IS 383 (2016), Coarse and fine aggregates for concrete-Specifications, Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi.

- IS 516 (1959), Methods of Tests for Strength of Concrete, Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi.

- ABAQUS Analysis User’s Manual, 2021.

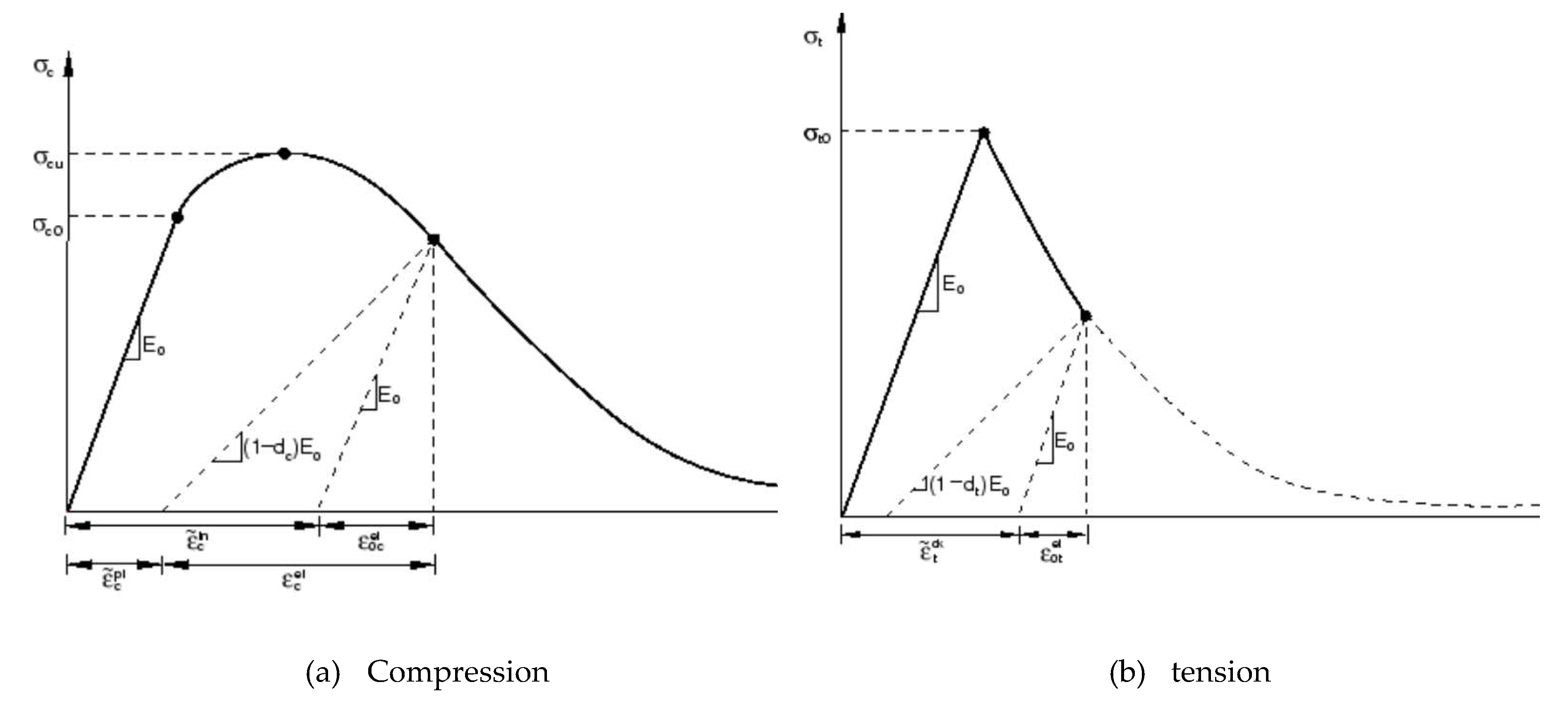

- Lee, J.; Fenves, G.L. Plastic-damage model for cyclic loading of concrete structures, Journal of Engineering Mechanics. 2018, 124, 892–900. [CrossRef]

- Lubliner, J.; Oliver, J.; Oller, S.; Onate, E. A plastic-damage model, International Journal of Solids and Structures. 1989, 25, 299–326. [CrossRef]

- Hafezolghorani, M.; Farzad, H.; Ramin, V.; Jaafar, M.S.B.; Karimzade, K. Simplified damage plasticity model for concrete. Structural Engineering International. 2017, 27, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhu, J.C.; Li, Y. A finite element analysis on compressive properties of ECC with PVA fibers. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 544, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hognestad, E. Study of combined bending and axial load in reinforced concrete members. Engineering Experiment Station, Illinois: University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, College of Engineering. 1951.

- Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Niu, S.; Ding, J. An experimental investigation on the failure behavior of a notched concrete beam strengthened with carbon fiber-reinforced polymer, International Journal of Polymer Science. 2015, Article ID 729320. [CrossRef]

- Tejaswini, T.; Raju, D.M.V.R. Analysis of RCC Beams using ABAQUS. Int. J. Innov. Eng. Technol. 2015, 5, 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Isa, M. Flexural Improvement of Plain Concrete Beams Strengthened With High Performance Fibre Reinforced Concrete. Niger. J. Technol. 2017, 36, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusallam, T.H. Analytical prediction of flexural behavior of concrete beams reinforced by FRP bars, Journal of Composite Materials. 1997, 31, 640–657. [CrossRef]

- Murad, Y.; Tarawneh, A.; Arar, F.; Al-Zu'bi, A.; Al-Ghwairi, A.; Al-Jaafreh, A.; Tarawneh, M. Flexural strength prediction for concrete beams reinforced with FRP bars using gene expression programming, Structures. 2021, 33, 3163–3172. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, A.; Sofi, M.; Lumantarna, E.; Zhou, Z.; Mendis, P. Flexural Capacity prediction model for steel fibre-reinforced concrete beams. International Journal of Concrete Structures and Materials. 2021, 15, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sr no. | Types of material | Specification | Applications |

| A. Concrete repair | |||

| 1 | Bonding primer | epoxy resin | used as bonding agent between old and new concrete structures |

| 2 | Crack repair | low viscosity injection resin | moisture incentive for sealing cracks> 5 mm |

| 3 | Site batch mortars | synthetic rubber emulsion | used for good adhesion and water resistance. |

| 4 | Smoothing mortars | epoxy modified cementitious, thixotropic, fine textured mortar | used for levelling and finishing of concrete, mortar or stone surfaces. |

| 5 | Structural injection material | low viscosity injection resin | moisture incentive for sealing cracks> 5 mm |

| B. Structural strengthening | |||

| 1 | Prefabricated CFRP plates | pultruded carbon fibre reinforced polymer (CFRP) laminates | strengthening concrete, timber, masonry, steel and fiber reinforced polymer structures. |

| 2 | FRP fabrics | uni-directional woven carbon fiber fabric | strengthening concrete, timber, masonry, steel and fiber reinforced polymer structures. |

| 3 | Structural adhesives | epoxy impregnation resin | structural strengthening application |

| C. Repairing Mortar | |||

| 1 | Cementitious mortars | polymer modified | repair mortar |

| 2 | Epoxy mortar | epoxy resin | for surface sealing, patch repair / filling mortar |

| 3 | Additives for mortars | synthetic rubber emulsion | for waterproofing and repair |

| Authors | Type of material | Specimen size | Loading | Properties of material | Remarks |

| [17] | Polymer mortars | 250 mm × 60 mm ×30 mm. and having notch 2 mm thick at different position 0, 24 mm, 48 mm and 72 mm towards the support. | Three-point load | - | Crack mouth opening displacement, crack tip opening displacement and values of energy release rate |

| [18] | Concrete and CFRP plate | 100mm×100mm×500mm Beam with notch at center which having depth 10mm, 20 mm & 30 mm, and wrapped with CFRP plates having length 100 mm, 200mm & 350 mm. Thickness of CFRP 1 mm and Adhesive 0.5 mm |

Three-point load |

fck=41.4 MPa EC=32.89 GPa ECFRP= 150 GPa Adhesive=4.3 GPa MIConcrete=8.3×106 mm4 |

with and without CFRP laminated plates, visually analysis the brittle failure, shear failures and delaminate failure. |

| [19] | Foamed concrete | Foamed concrete beam 840 mm×100mm×100mm having notch (5 mm thick 42 mm height ) at center. | Three-point load test of Beam |

EFoamed Concrete=1000 GPa µFoamed Concrete= 0.2, ε = 0.2, φ = 15° |

XFEM model of foamed concrete |

| [20] | Foamed concrete | Foamed concrete beam 750 mm×150mm×150mm having V-notch 30 mm long at center. | Cube compressive strength and three point load test | ρconcrete =2400 kg/ m3 , ρfoamed concrete=1400-1600 kg/ m3 | compressive strength of cube and fracture energy of foam concrete is lower |

| [21] | RCC Beam, CFRP & Adhesive | RCC beam 3000 mm ×200 mm×300 mm with notch at center of beam and CFRP plates 4 mm thick apply with 2 mm thick layer of adhesive. | Three-point load | EC=30 GPa ECFRP=140 GPa EAdhisieve=3 GPa µc=0.18 µCFRP=0.28 µAdhesive=0.35 |

CFRP plates bonding with surface of Beam and significantly enhance the stiffness and ultimate load |

| [22] | PCC beam | 1640 mm × 200 mm × 400 mm with notch at center (a/d = 0.5). | Three point load bending test |

EC=30,570MPa fck=21.9 MPa ftk=2.4 MPa |

Acoustic Emission (AE) and Digital Image Correlation (DIC) techniques. |

| [23] | PCC beam with steel fiber hook | 600 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm plain concrete beam with different notch depth 13 mm, 25 mm and 50 mm at center and a/d ratio is 0.08, 0.16 and 0.33. | Three point load | Size of steel fiber 50 mm length and diameter 1 mm and tensile strength 1130 MPa. water cement ratio is 0.55 and cement :sand: aggregate ratio is 1:2.93:2.31 |

a/d ratio notch is increase 0.08., 0.16 & 0.33 load carrying capacity decrease. Due to presence of high volume of steel fiber fracture energy increases with increases a/d ratio |

| Authors | Materials | Name of bacteria | Preparation of specimen and curing | Test method | Result and discussion |

| [31] | Cement, sand, aggregate, bacteria liquid, Cyclic En riched Ureolytic powder (CERUP), and activated compact denitrifying Core (ACDC) granules | B.Cohni | Specimens cured in water for 28 days | Compressive strength , water absorption and recovery of water tightness | Compressive strength increase by 25%, water absorption decrease, due to aerobic oxidation of organic carbon O2 consumption by bacteria so it will reduce the rebar corrosion |

| [32] | Cement, sand, aggregate, with ratio of 1:2.5 water Bacterial Liquid Clay ball. |

Genus. Bacillus | Specimens cured in water and wet/dry cycle 28 and 56 days. | Crack water permeability Recovery of water-tightness Oxygen consumption measurements and ESEM analysis |

Cracked permeability lower than normal concrete |

| [28] | Portland slag cement and fine sand ratio of 1:6, Bacterial solution w/c 0.55 |

B.Cohni | Specimen cured in water for 28 days | Standard consistency, Setting time, soundness cement, compressive strength, sorptivity, drying shrinkage, microstructure and morphology, field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques | 28 days compressive strength increased by 49.8% and sorpvity decrease |

| [29] | Portland cement, sand fly ash, silica fume, calcium lactate, calcium acetate and encapsulated material. | S. Pastteurii and others ureolytic bacteria. | Specimen cured for 28 days. | setting time of concrete, Compressive strength, permeability, Chloride ion permeability, and microstructure Calcite. | Compressive strength increase and permeability decreases. |

| [33] | Cement send bacteria liquid encapsulated material | Ureolytic bacteria | Specimen cured in buffer solution for 7 and 28 days. | Scanning electron microscope, Compressive strength, permeability |

Permeability decrease |

| [34] | Portland flyash cement sand with ratio 1:3 bacteria perlite, sodium silicate, water, calcium acetate, yeast extract and w/c 0.5. | B.pseudoformu | Specimens cured in controlled environment then after demoulding specimen cured in water at 20 °C until 28 days. Cracked sample cured in moist and humid environment for 165 days |

Surface water absorption and visualisation of crack healing | water absorption decreases |

| [30] | OPC, sand w/c 0.46 and buffer solution | B.Pasturi | Specimen cured in humidity chamber with relative humidity 100% for 24 h. After demolding bacterial specimen were cured in buffer solution for 28 days | Compressive strength and water absorption | 28 days compressive strength increased by 33% and water absorption |

| [35] | Portland cement, sand water, encapsulation | Ureolytic bacteria | Specimen cured for 28, 60, 90, 365, 730 days | Compressive strength, flexural strength and water absorption | Compressive strength and flexural strength increases, Construction cost increase but maintenance cost decrease |

| [36] | Portland cement, sand water, encapsulation | Bacillus Cereus | Specimen cured for 180 days | compressive and split tensile strength, ultrasonic pulse velocity and water absorption capacity | compressive and split tensile strength were improved and reducing water absorption capacity |

| References | Material properties | Dimensions | One-point maximum failure load (N) | % difference | |

| Published results | Present study results | ||||

| [46] | E= 32.89 GPa and fck=41.2 MPa | 500mm×100mm×100mm, notch 10 mm ×10 mm× 100 mm. |

6933.3 | 6606 | 4.72 |

| [47] | fck=38.24 MPa | L=1200mm, d=200 and b=100mm. | 11200 | 10770 | 3.83 |

| [48] | fck=54MPa, ftk=3.16 | L=1400 mm, d=230 mm and b=140 mm. | 16000 | 15963 | 0.23 |

| Material | fck (MPa) | ftk (MPa) | Modulus of elasticity (MPa) | Density (kg/m3) | Poisson’s ratio | Dilation Angle | Viscosity |

| Concrete | 40 | 4.6 | 32890 | 2400 | 0.2 | 31⁰ | 0.00001 |

| Repairing material | Density | Compressive strength (N/mm2) | Modulus of elasticity (MPa) | Poisson’s ratio |

| Cement mortar | 2200 (kg/m3) | 36.22 in 28 days | 14108.08 [44] | 0.2 |

| Bacterial mortar | 2200 (kg/m3) | 63.43 in 28 days | 30387.43 | 0.2 |

| Adhesive | 1.8 (kg/L) | 65 in 15 days | 11000 | 0.25 |

| Parameters | Experimental | Numerical |

| Coefficients | p1 = -0.0364, p2 = 7.745 | p1 = -0.0496, p2 = 8.259 |

| R2 | 0.984 | 0.973 |

| RMSE | 0.288 | 0.522 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).