Submitted:

06 February 2024

Posted:

07 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cell Culture

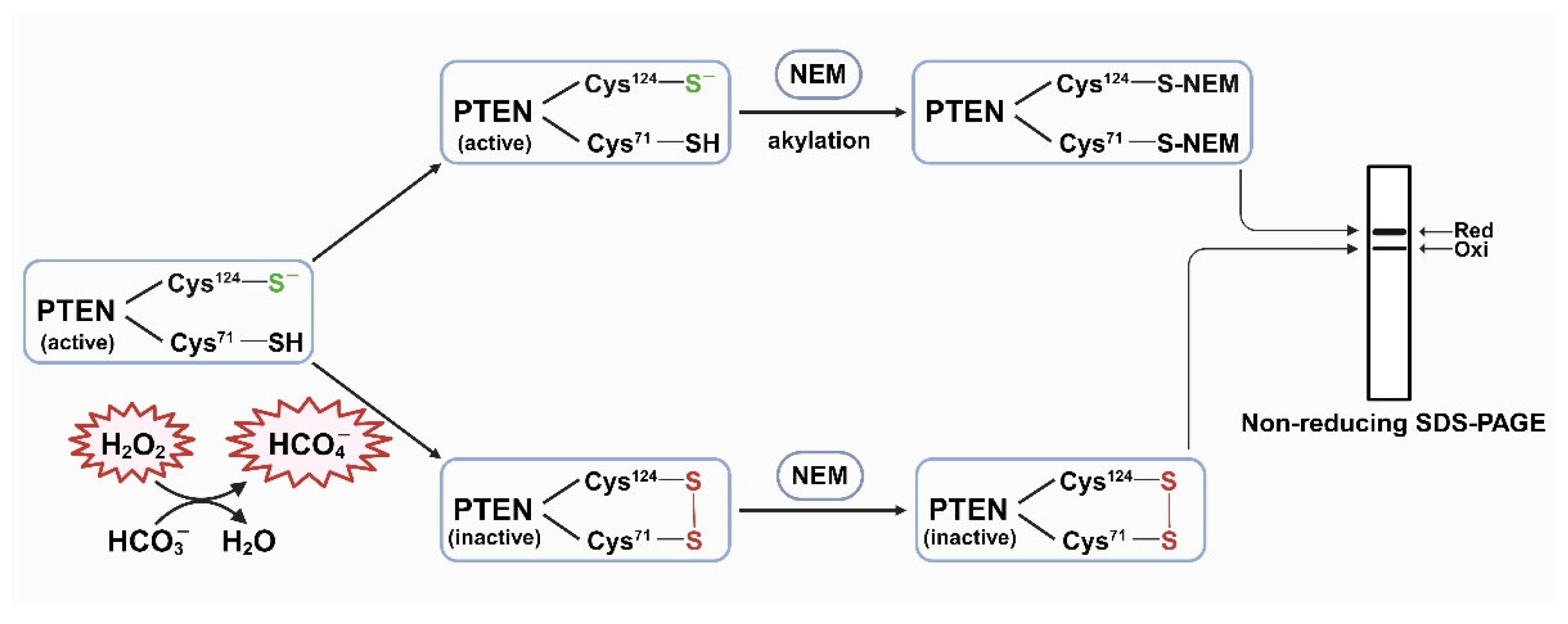

2.3. Immunoblot Analysis of H2O2-Induced Oxidation of PTEN

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

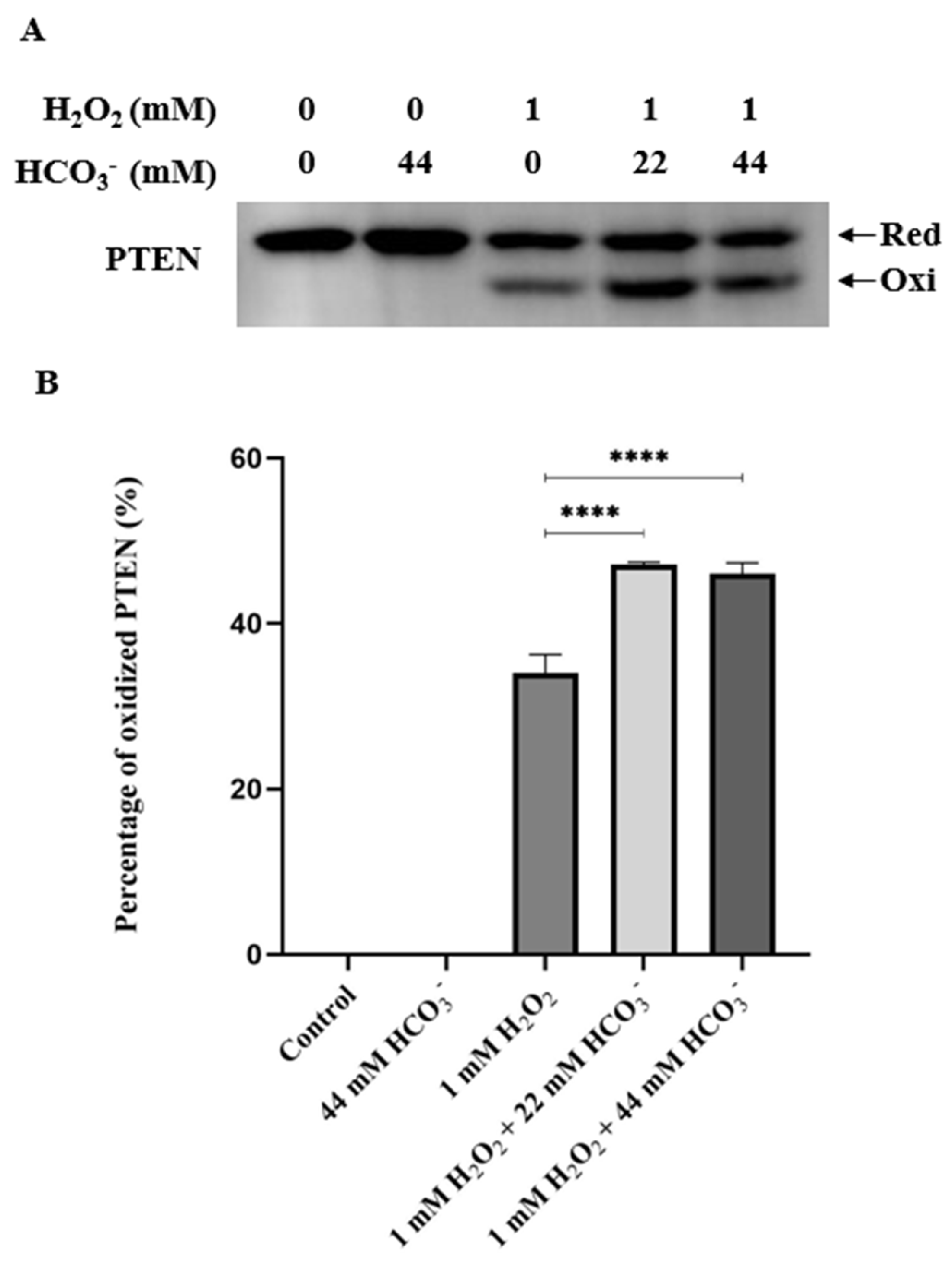

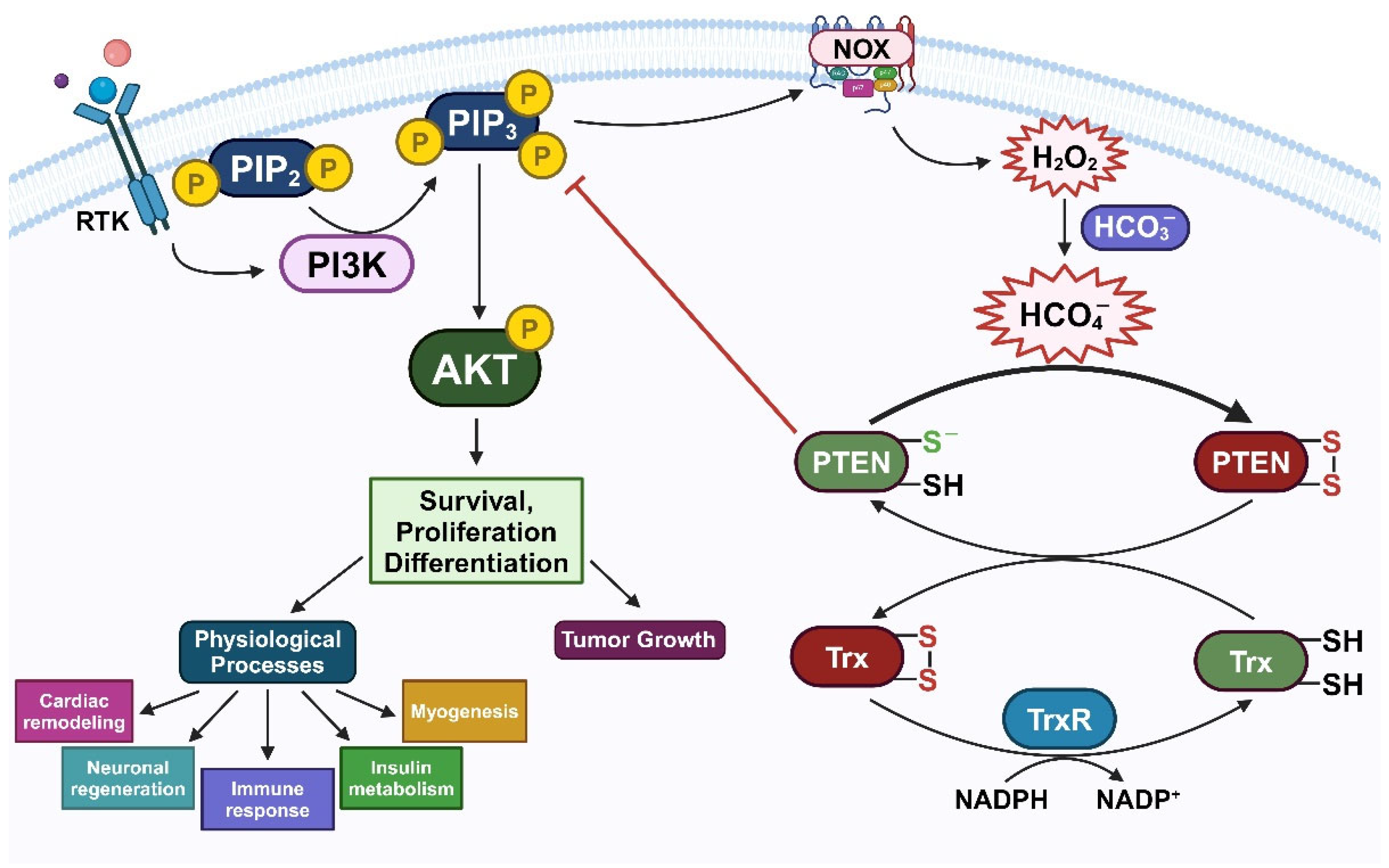

The Presence of HCO3- Potentiates the PTEN Oxidation by H2O2

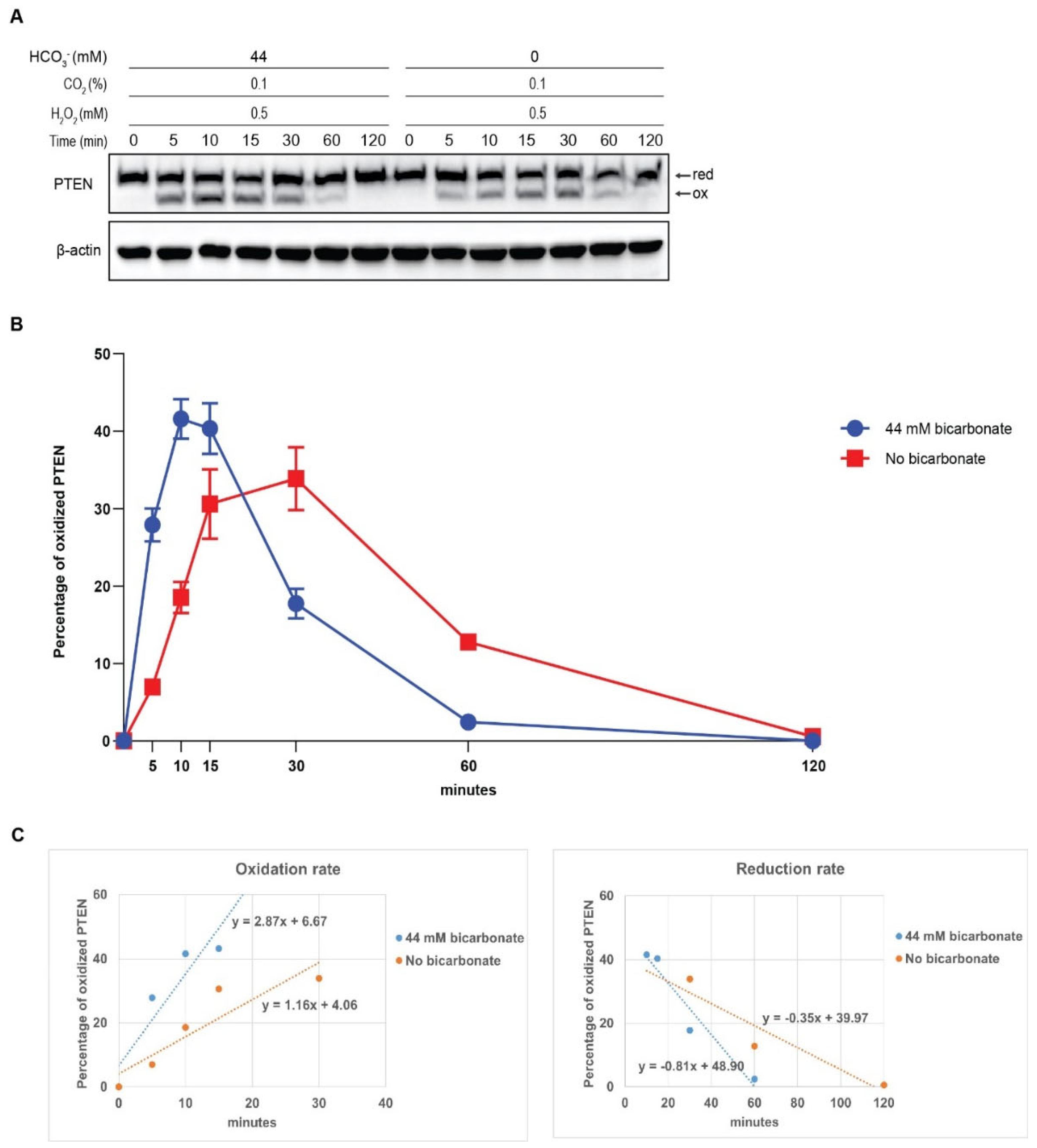

The Presence of HCO3- Accelerates the Redox Regulation of PTEN by H2O2

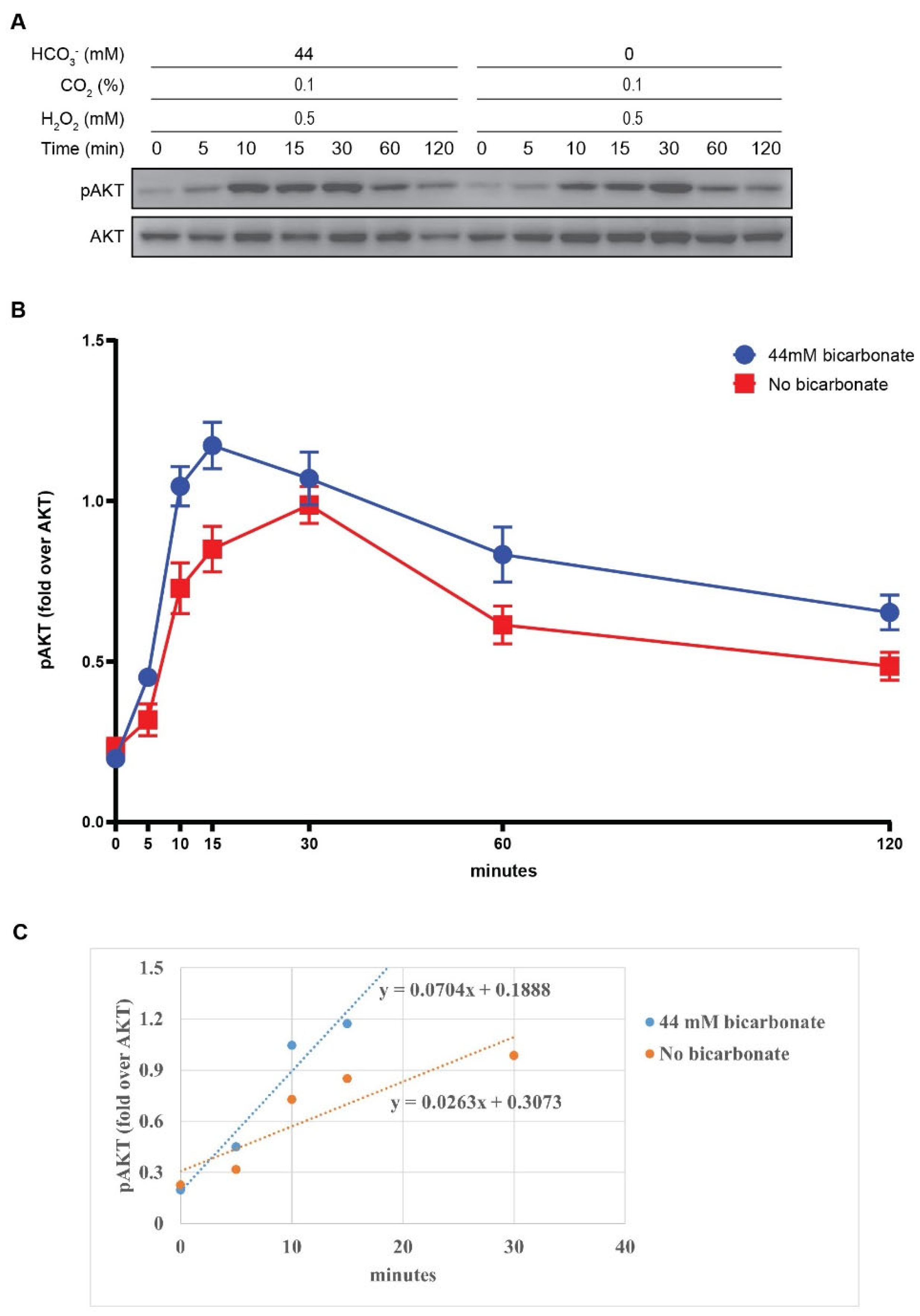

The Activation of PI3K/AKT Pathway via PTEN Oxidation by H2O2 and HCO3-

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rhee, S.G.; Bae, Y.S.; Lee, S.-R.; Kwon, J. Hydrogen peroxide: a key messenger that modulates protein phosphorylation through cysteine oxidation. Science’s STKE 2000, 2000, pe1-pe1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, H.J.; Maiorino, M.; Ursini, F. Signaling functions of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.G. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science 2006, 312, 1882–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Geer, P.; Hunter, T.; Lindberg, R.A. Receptor protein-tyrosine kinases and their signal transduction pathways. Annual review of cell biology 1994, 10, 251–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denu, J.M.; Dixon, J.E. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: mechanisms of catalysis and regulation. Curr Opin Chem Biol 1998, 2, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denu, J.M.; Tanner, K.G. Specific and reversible inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases by hydrogen peroxide: evidence for a sulfenic acid intermediate and implications for redox regulation. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 5633–5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-R.; Chen, M.; Pandolfi, P.P. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor: new modes and prospects. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2018, 19, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-O.; Yang, H.; Georgescu, M.-M.; Di Cristofano, A.; Maehama, T.; Shi, Y.; Dixon, J.E.; Pandolfi, P.; Pavletich, N.P. Crystal structure of the PTEN tumor suppressor: implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity and membrane association. Cell 1999, 99, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambolic, V.; Suzuki, A.; De La Pompa, J.L.; Brothers, G.M.; Mirtsos, C.; Sasaki, T.; Ruland, J.; Penninger, J.M.; Siderovski, D.P.; Mak, T.W. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell 1998, 95, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, N.R.; Bennett, D.; Lindsay, Y.E.; Stewart, H.; Gray, A.; Downes, C.P. Redox regulation of PI 3-kinase signalling via inactivation of PTEN. The EMBO journal 2003, 22, 5501–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, R. PTEN inhibition in human disease therapy. Molecules 2018, 23, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-R.; Yang, K.-S.; Kwon, J.; Lee, C.; Jeong, W.; Rhee, S.G. Reversible inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by H2O2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 20336–20342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.G.; Chae, H.Z.; Kim, K. Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free radical biology and Medicine 2005, 38, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.G.; Woo, H.A.; Kil, I.S.; Bae, S.H. Peroxiredoxin functions as a peroxidase and a regulator and sensor of local peroxides. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 4403–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, A.; Nelson, K.J.; Parsonage, D.; Poole, L.B.; Karplus, P.A. Peroxiredoxins: guardians against oxidative stress and modulators of peroxide signaling. Trends in biochemical sciences 2015, 40, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flangan, J.; Jones, D.P.; Griffith, W.P.; Skapski, A.C.; West, A.P. On the existence of peroxocarbonates in aqueous solution. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications 1986, 20–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhmutova-Albert, E.V.; Yao, H.; Denevan, D.E.; Richardson, D.E. Kinetics and mechanism of peroxymonocarbonate formation. Inorganic chemistry 2010, 49, 11287–11296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radi, R. Interplay of carbon dioxide and peroxide metabolism in mammalian cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2022, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, D.E.; Yao, H.; Frank, K.M.; Bennett, D.A. Equilibria, kinetics, and mechanism in the bicarbonate activation of hydrogen peroxide: oxidation of sulfides by peroxymonocarbonate. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2000, 122, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, D.F.; Cerchiaro, G.; Augusto, O. A role for peroxymonocarbonate in the stimulation of biothiol peroxidation by the bicarbonate/carbon dioxide pair. Chem Res Toxicol 2006, 19, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Singh, H.; Parsons, Z.D.; Lewis, S.M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Seiner, D.R.; LaButti, J.N.; Reilly, T.J.; Tanner, J.J.; Gates, K.S. The biological buffer bicarbonate/CO2 potentiates H2O2-mediated inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2011, 133, 15803–15805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnell, M.; Cheng, Q.; Rizvi, S.H.M.; Pace, P.E.; Boivin, B.; Winterbourn, C.C.; Arnér, E.S. Bicarbonate is essential for protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) oxidation and cellular signaling through EGF-triggered phosphorylation cascades. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2019, 294, 12330–12338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.; Chen, Y.; Hernandez, C.M.; Forster, F.; Dagnell, M.; Cheng, Q.; Saei, A.A.; Gharibi, H.; Lahore, G.F.; Åstrand, A. Redox regulation of PTPN22 affects the severity of T-cell-dependent autoimmune inflammation. Elife 2022, 11, e74549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorai, T.; Sawczuk, I.S.; Pastorek, J.; Wiernik, P.H.; Dutcher, J.P. The role of carbonic anhydrase IX overexpression in kidney cancer. European journal of cancer 2005, 41, 2935–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-J.; Ahn, Y.; Park, I.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, I.; Kim, H.W.; Ku, C.-S.; Chay, K.-O.; Yang, S.Y.; Ahn, B.W. Assay of the redox state of the tumor suppressor PTEN by mobility shift. Methods 2015, 77, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonks, N.K. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: from genes, to function, to disease. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2006, 7, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeth, J.D. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nature Reviews Immunology 2004, 4, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, N.R. The redox regulation of PI 3-kinase-dependent signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 2006, 8, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downes, C.P.; Ross, S.; Maccario, H.; Perera, N.; Davidson, L.; Leslie, N.R. Stimulation of PI 3-kinase signaling via inhibition of the tumor suppressor phosphatase, PTEN. Adv Enzyme Regul 2007, 47, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cully, M.; You, H.; Levine, A.J.; Mak, T.W. Beyond PTEN mutations: the PI3K pathway as an integrator of multiple inputs during tumorigenesis. Nature Reviews Cancer 2006, 6, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Semenza, G.L. PTEN activity is modulated during ischemia and reperfusion: involvement in the induction and decay of preconditioning. Circulation research 2005, 97, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervera, A.; De Virgiliis, F.; Palmisano, I.; Zhou, L.; Tantardini, E.; Kong, G.; Hutson, T.; Danzi, M.C.; Perry, R.B.; Santos, C.X.C.; et al. Reactive oxygen species regulate axonal regeneration through the release of exosomal NADPH oxidase 2 complexes into injured axons. Nat Cell Biol 2018, 20, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, H.-J.; Liu, P.; Bajrami, B.; Xu, Y.; Park, S.-Y.; Nombela-Arrieta, C.; Mondal, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chai, L. Myeloid cell-derived reactive oxygen species externally regulate the proliferation of myeloid progenitors in emergency granulopoiesis. Immunity 2015, 42, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, K.; Deng, H.; Fukushima, A.; Cai, X.; Boivin, B.; Galic, S.; Bruce, C.; Shields, B.J.; Skiba, B.; Ooms, L.M. Reactive oxygen species enhance insulin sensitivity. Cell metabolism 2009, 10, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, T.G.; Park, S.; Yun, H.R.; Nguyen, N.N.Y.; Jo, Y.H.; Jang, M.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kang, I.; et al. Mitochondrial ROS-derived PTEN oxidation activates PI3K pathway for mTOR-induced myogenic autophagy. Cell Death Differ 2018, 25, 1921–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Huu, T.; Park, J.; Zhang, Y.; Park, I.; Yoon, H.J.; Woo, H.A.; Lee, S.R. Redox Regulation of PTEN by Peroxiredoxins. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Schulte, J.; Knight, A.; Leslie, N.R.; Zagozdzon, A.; Bronson, R.; Manevich, Y.; Beeson, C.; Neumann, C.A. Prdx1 inhibits tumorigenesis via regulating PTEN/AKT activity. Embo j 2009, 28, 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Park, J.; Han, S.-J.; Yang, S.Y.; Yoon, H.J.; Park, I.; Woo, H.A.; Lee, S.-R. Redox regulation of tumor suppressor PTEN in cell signaling. Redox biology 2020, 34, 101553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadev, K.; Zilbering, A.; Zhu, L.; Goldstein, B.J. Insulin-stimulated hydrogen peroxide reversibly inhibits protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1b in vivo and enhances the early insulin action cascade. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 21938–21942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.-C.; Buckley, D.A.; Galic, S.; Tiganis, T.; Tonks, N.K. Regulation of insulin signaling through reversible oxidation of the protein-tyrosine phosphatases TC45 and PTP1B. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 37716–37725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boosani, C.S.; Gunasekar, P.; Agrawal, D.K. An update on PTEN modulators–a patent review. Expert opinion on therapeutic patents 2019, 29, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).