Submitted:

05 February 2024

Posted:

06 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Soil Sampling

2.2. Production of extracellular lytic enzymes:

2.2.1. Cellulase:

2.2.2. Amylase:

2.2.3. Lipase:

2.2.4. Protease:

2.2.5. Urease:

2.2.6. Chitinase:

2.3. PGPR features:

2.3.1. Nitrogen fixation:

2.3.2. Solubilization of phosphates:

2.3.3. Production of ammonia (NH3):

2.3.4. Production of hydrogen cyanide (HCN):

2.3.5. Production of indole 3-acetic acid (IAA)

2.4. Molecular identification:

2.5. Antifungal activity

2.5.1. In-vitro tests:

2.5.2. Characterization of bacterial antifungal metabolites:

2.5.3. In-vivo test:

2.6. Plant Growth Stimulation Tests

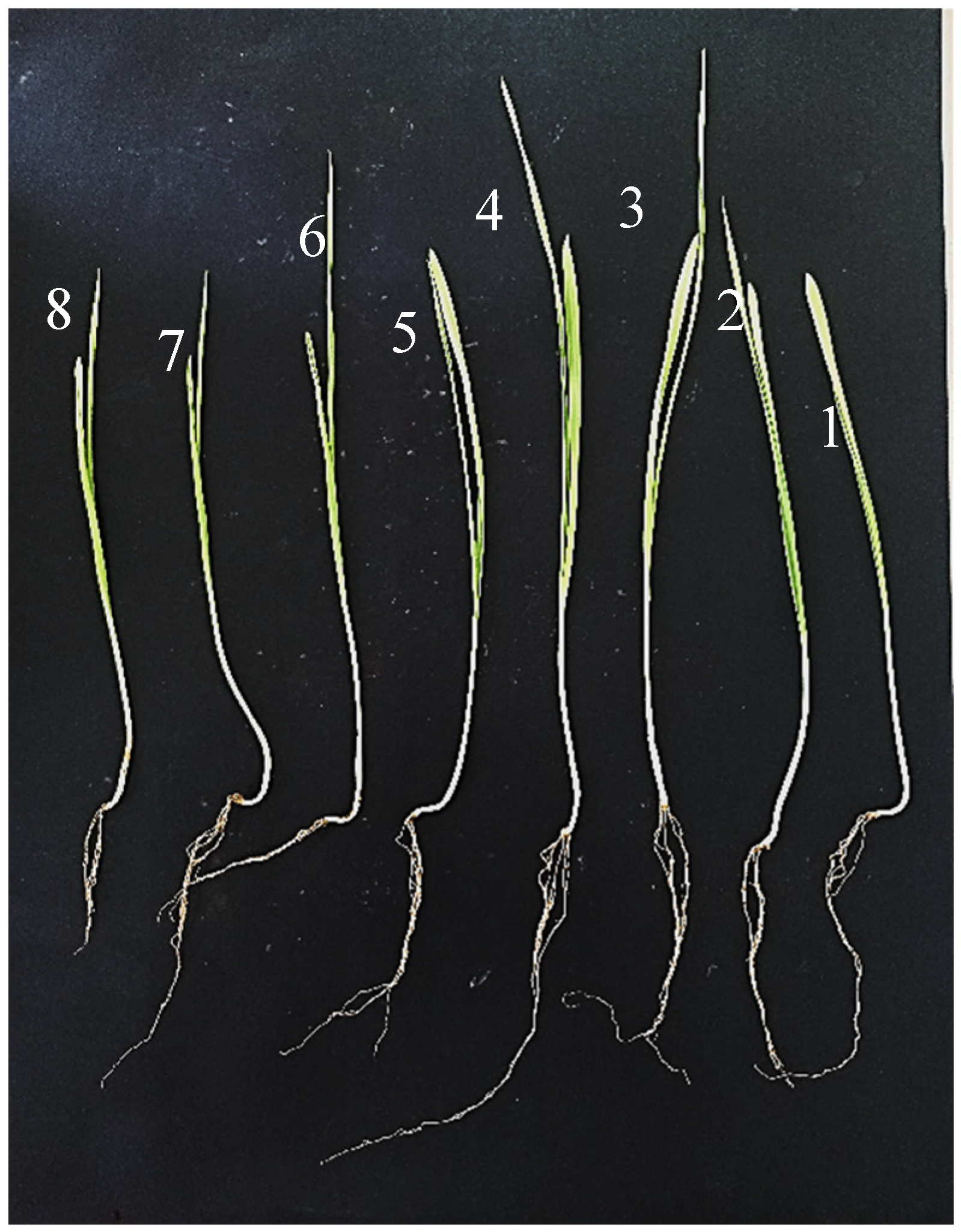

2.6.1. Potting

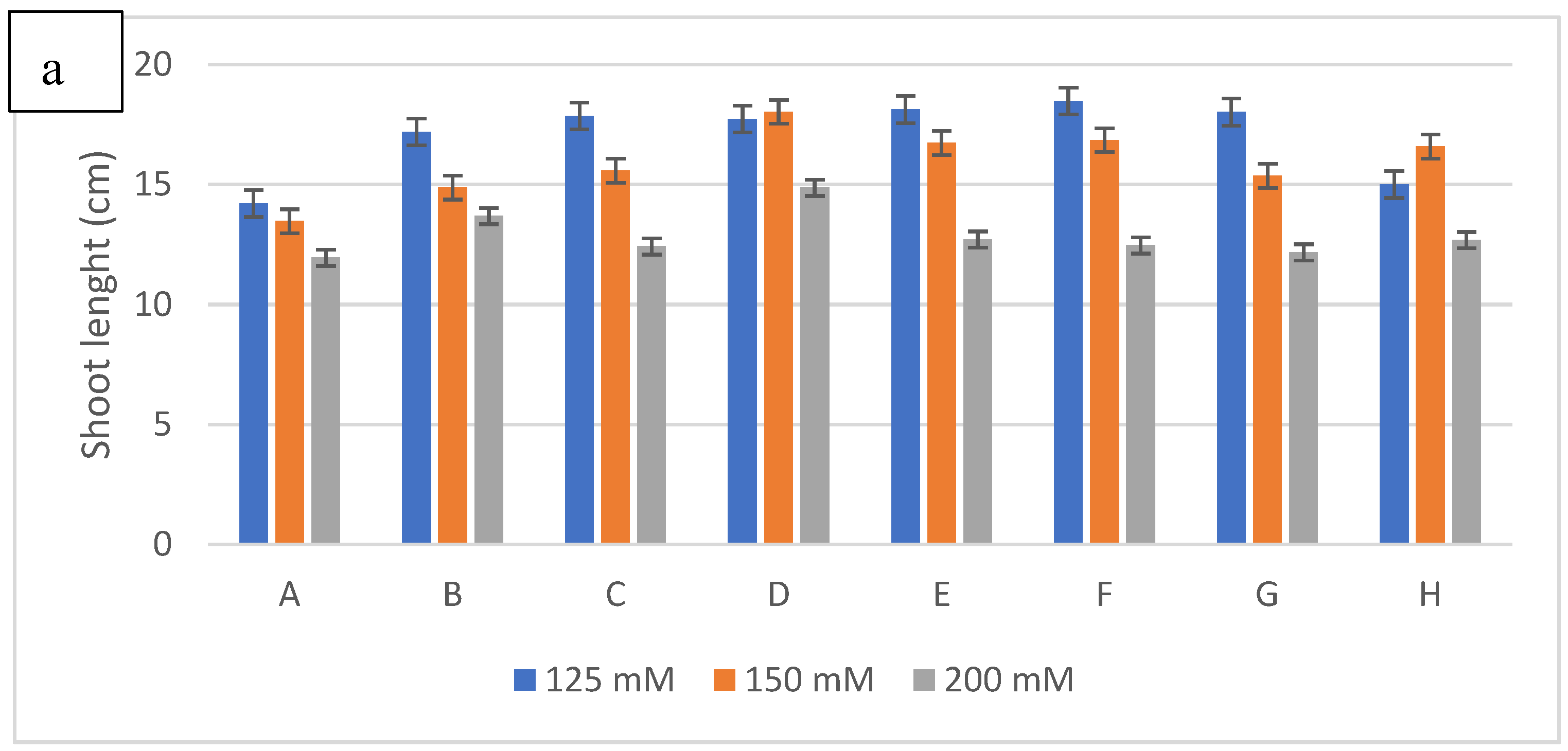

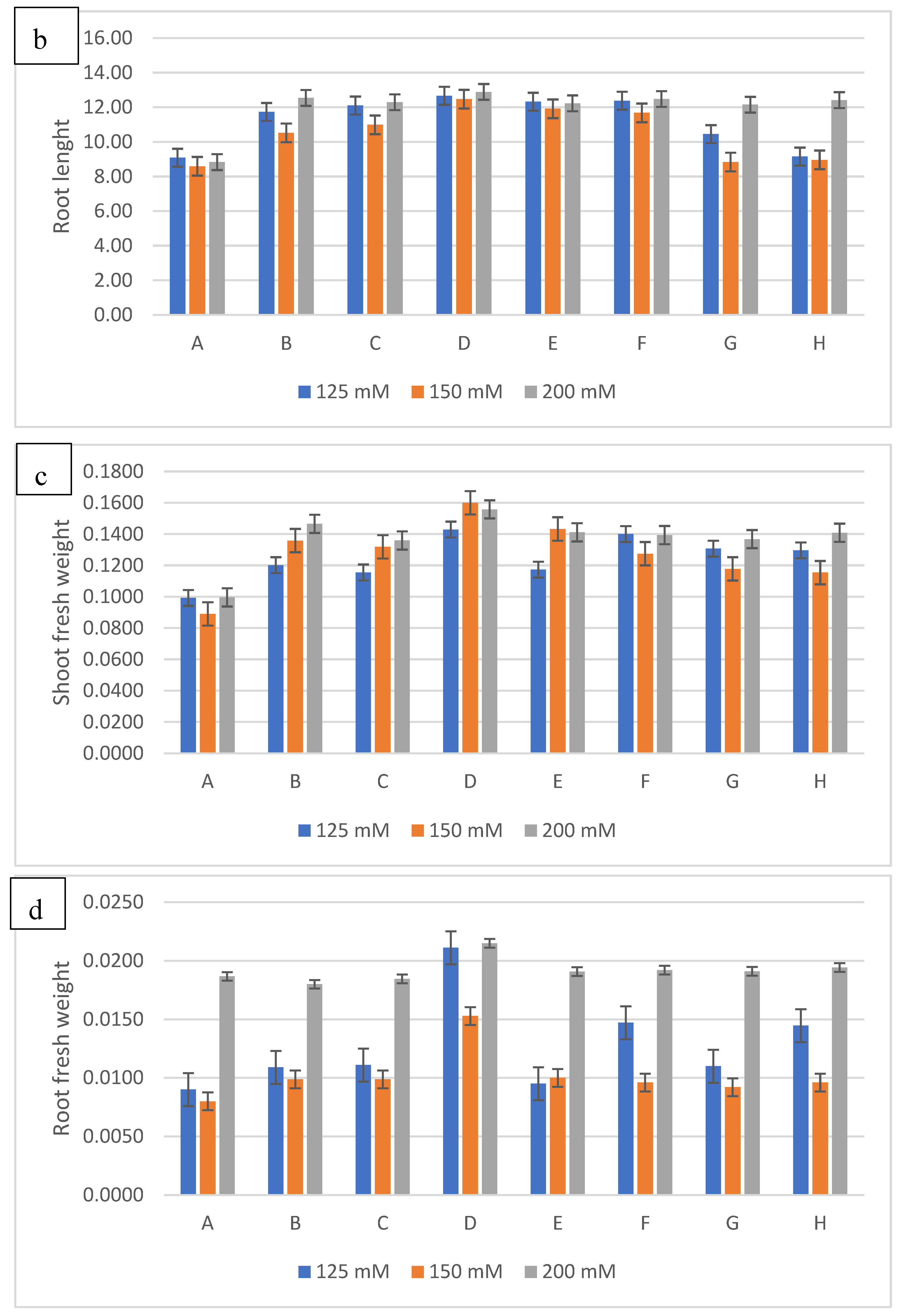

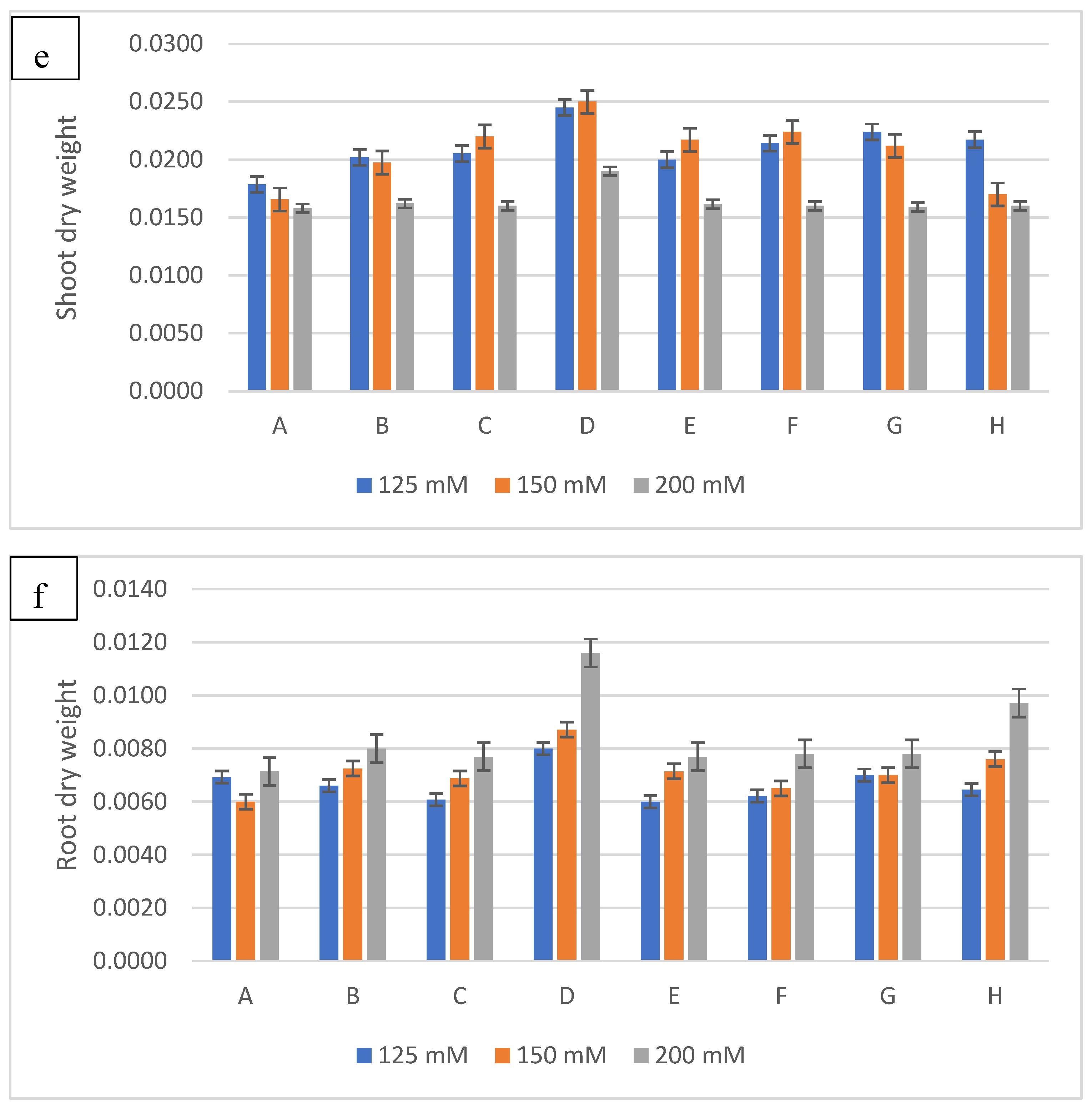

2.6.2. Evaluation of plant growth factors under salt stress

2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Researching traits that promote plant growth

3.2. Molecular identification

3.3. Antifungal activity

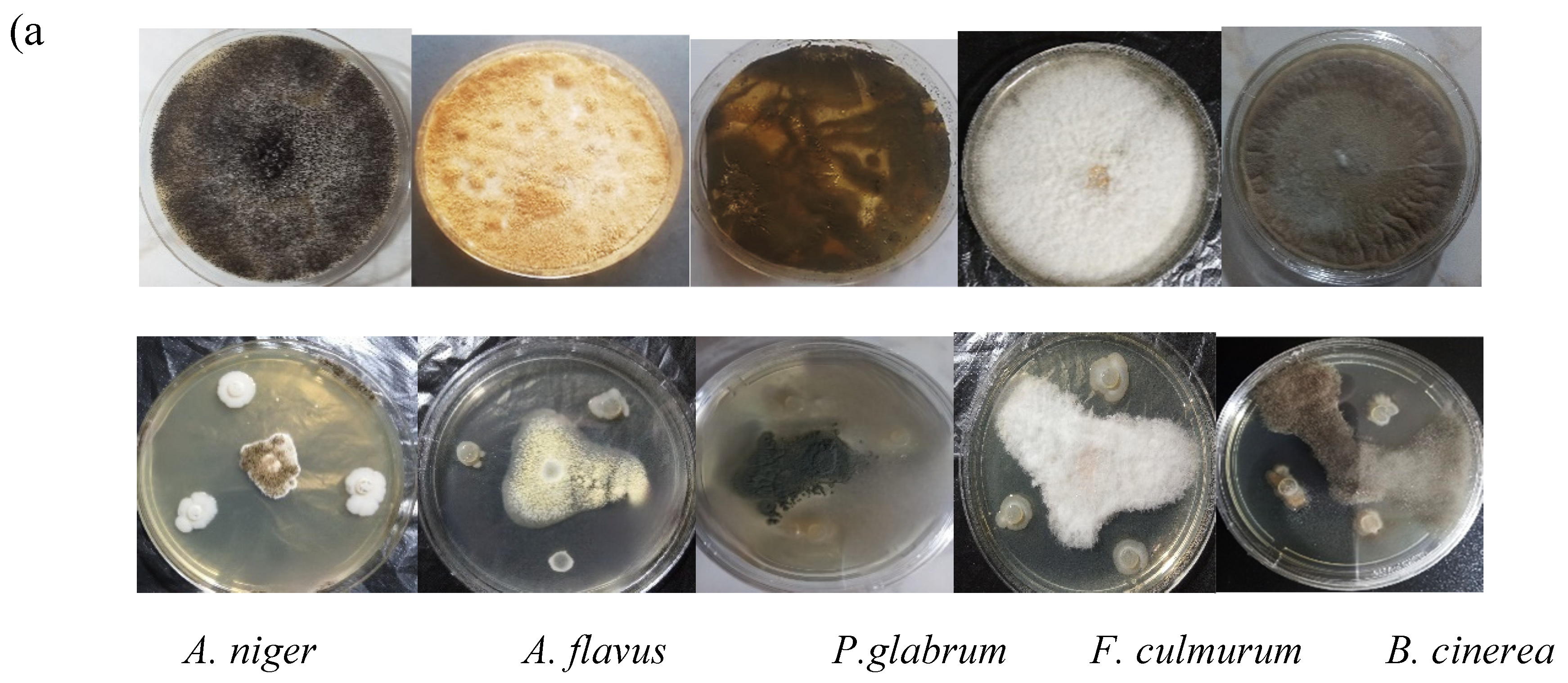

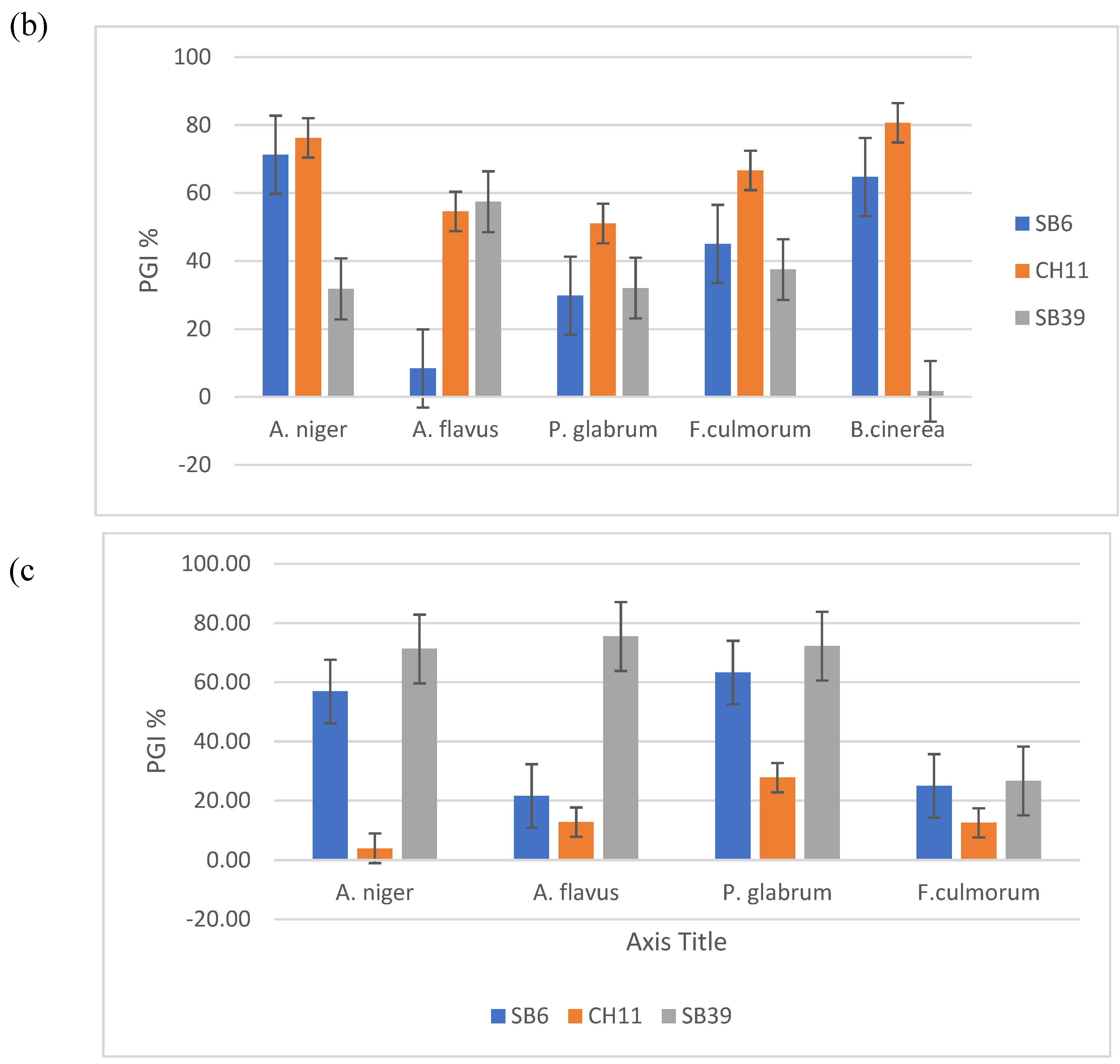

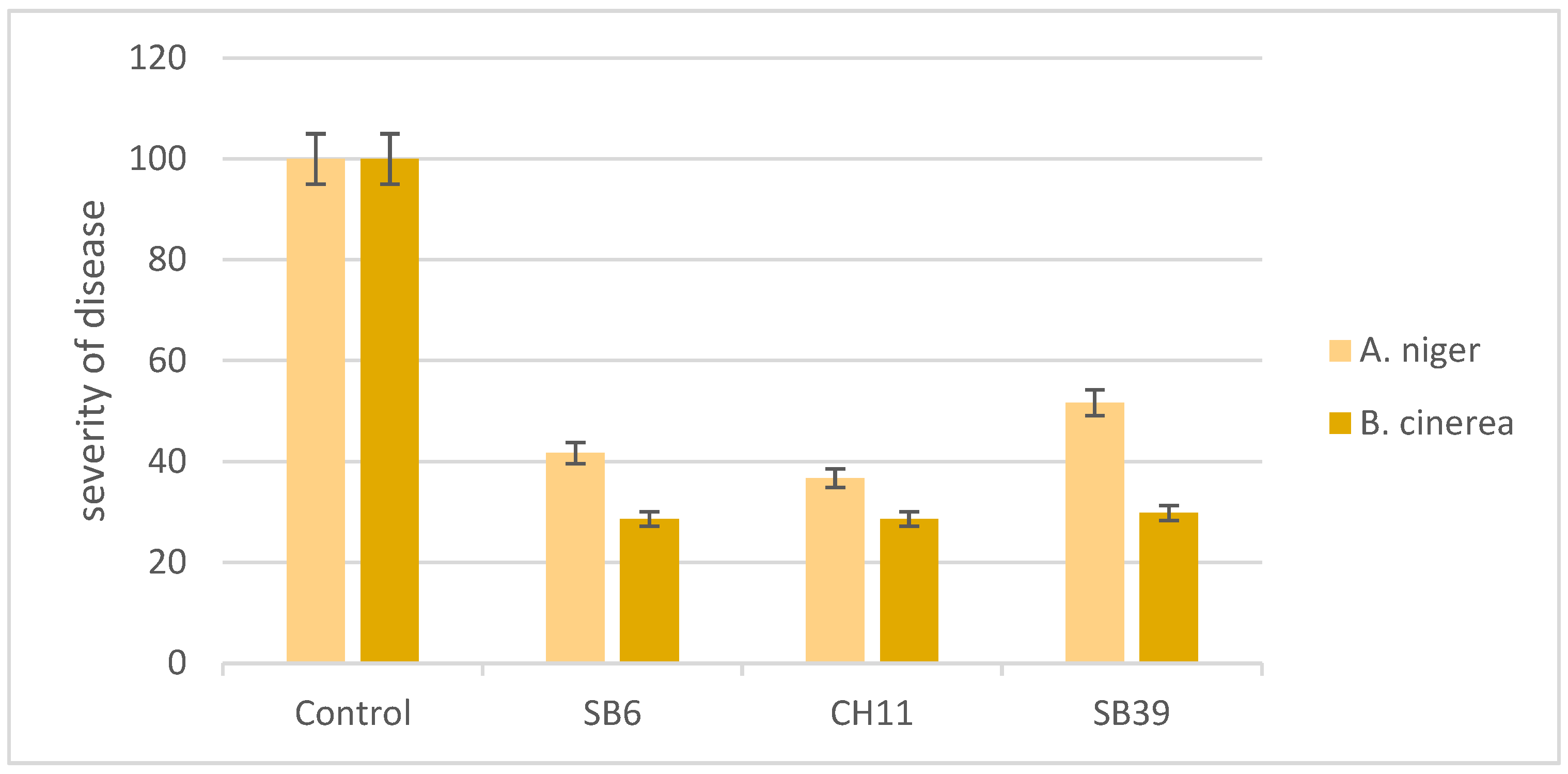

3.3.1. Direct inhibition of mycelial growth

3.3.2. Indirect inhibition of mycelial growth

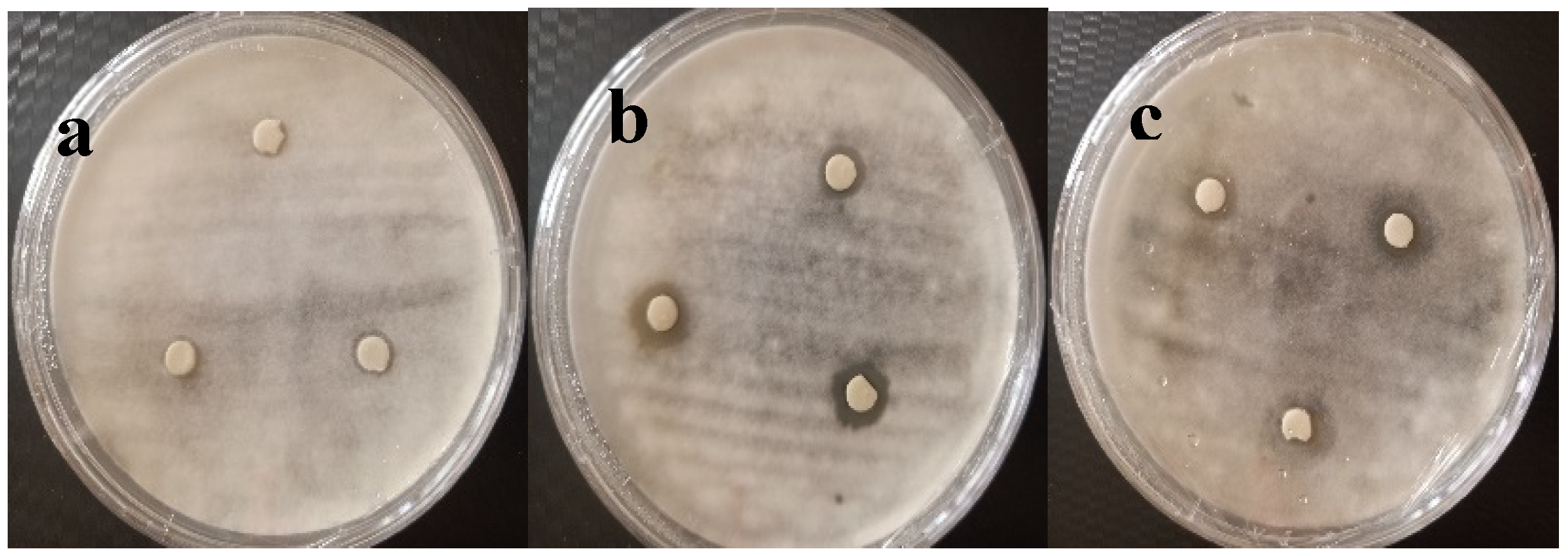

3.3.3. Inhibition of mycelial growth by volatile substances

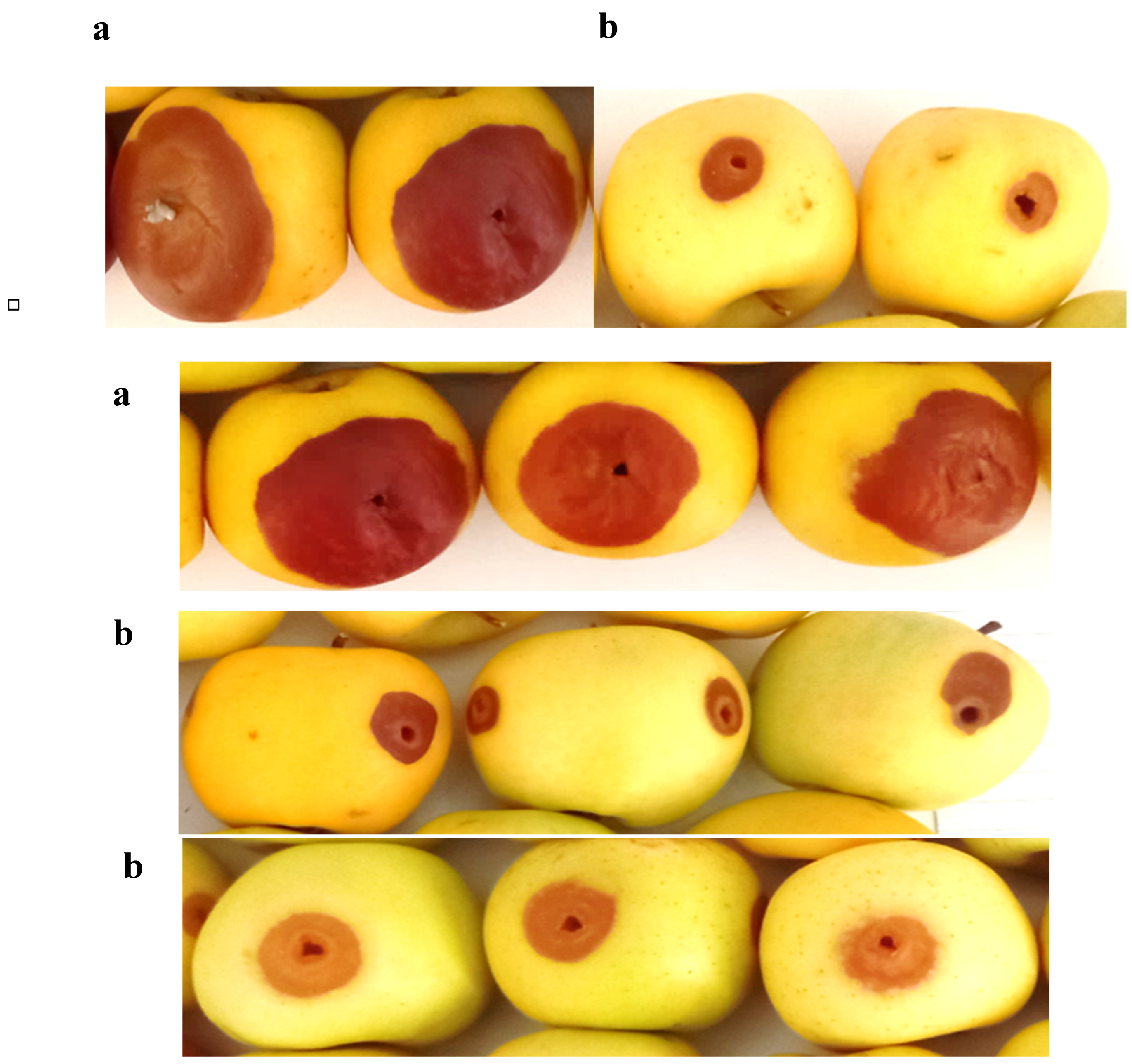

3.3.4. Bioassay on apples

3.3.5. Characterization of bacterial antifungal metabolites

3.4. Tests to stimulate the growth of wheat plants subjected to salt stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- El Hasini, S.; Iben. Halima, O.; El. Azzouzi, M.; Douaik, A.; Azim, K.; Zouahri, A. Organic and inorganic remediation of soils affected by salinity in the Sebkha of Sed El Mesjoune – Marrakech (Morocco), Soil and Tillage Research. 2019, 193, 153-160. 2019, 193, 153–160. [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation, Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2015, 22 (2), 123-131. [CrossRef]

- Cheik, S. La salinisation des sols, un défi majeur pour la sécurité alimentaire mondiale. 2021. Project No. IC 18CT 96-0055, pp: 152-226.

- Pimentel, D.; Berger, B.; Filiberto, D.; Newton, M.; Wolfe, B.; Karabinakis, E.; Clark, S.; Poon, E.; Abbett, E.; Nandagopal, S. Water Resources: Agricultural and Environmental Issues, BioScience. 2004, 54 (10), 909–918. [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.M.A.; Serralheiro, R.P. Soil Salinity: Effect on Vegetable Crop Growth. Management Practices to Prevent and Mitigate Soil Salinization. Horticulturae. 2017, 3, 30. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Chowdhury, N. Salt Stress in Plants and Amelioration Strategies: A Critical Review. Abiotic Stress in Plants. 2020, Chapter 19. [CrossRef]

- Egamberdieva, D.; Wirth, S.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D.; Mishra, J.; Arora, N.K. Salttolerant plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for enhancing crop productivity of saline soils. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2791. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.A.; Kumar, V.; Bhat, M.A.; Wani, I.A.; Dar, F.L.; Farooq, I.; Bhatti, F.; Koser, R.; Rahman, S.; Jan, A.T. Mechanistic insights of the interaction of plant growthpromoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) with plant roots toward enhancing plant productivity by alleviating salinity stress. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Miao, Q.; Feng, W.W.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xing, K.; Jiang, J.H. Biodiversity and plant growth promoting traits of culturable endophytic actinobacteria associated with Jatropha curcas L. growing in Panxi dry-hot valley soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2015, 93, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, R.; Rokem, J.S.; Ilangumaran, G.; et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization of biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Z.; He, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Ye, B.C. Plant growth promotion and alleviation of salinity stress in Capsicum annuum L. by Bacillus isolated from saline soil in Xinjiang. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 164, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, C.B.; Tomás, M.S.J.; Viruel, E.; Ferrero, M.A.; Lucca, M.E. Development of low-cost formulations of plant growth-promoting bacteria to be used as inoculants in beneficial agricultural technologies. Microbiol. Res. 2019, 219, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnav, A.; Singh, J.; Singh, P.; Rajput, R.S.; Singh, H.B.; Sarma, B.K. Sphingobacterium sp. BHU-AV3 induces salt tolerance in tomato by enhancing antioxidant activities and energy metabolism. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, B.; Cai, S.; and al. Identification of rhizospheric actinomycete Streptomyces lavendulae SPS-33 and the inhibitory effect of its volatile organic compounds against Ceratocystis Fimbriata in postharvest sweet potato (Ipomoea Batatas (L.) Lam.). Microorganisms. 2020, 8 (3), 319. [CrossRef]

- Zainab, N.; Amna, Din, B.U.; et al. Deciphering metal toxicity responses of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) with exopolysaccharide and ACC-deaminase producing bacteria in industrially contaminated soils. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 152, 90–99. [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Mosqueda, M.D.C.; Glick, B.R.; Santoyo, G. ACC deaminase in plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB): an efficient mechanism to counter salt stress in crops. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 235, 126439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Esawi, M.; Glascoe, A.; Engle, D.; Ritz, T.; Link, J.; Ahmad, M. Cellular metabolites modulate in vivo signaling of Arabidopsis cryptochrome-1. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10(9), e1063758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Feng, W.W.; Zhang, Y.J.; Wang, T.T.; Xiong, Y.W.; Xing, K. Diversity of bacterial microbiota of coastal halophyte Limonium sinense and amelioration of salinity stress damage by symbiotic plant growth-promoting actinobacterium Glutamicibacter halophytocola KLBMP 5180. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84 (19) e01533-18. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.W.; Gong, Y.; Li, X.W.; Chen, P.; Ju, X.Y.; Zhang, C.M.; Yuan, B.; Lv, Z.P.; Xing, K.; Qin, S. Enhancement of growth and salt tolerance of tomato seedlings by a natural halotolerant actinobacterium Glutamicibacter halophytocola KLBMP 5180 isolated from a coastal halophyte. Plant Soil. 2019, 445, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabli, N.; Nabti, E.H.; Dahel, D.; Mokrane, N.; Manyani, H.; Dary, M.; Megias, M. G. Impact of Diazotrophic Bacteria on Germination and Growth of Tomato, with Bio-control Effect, Isolated from Algerian Soil.J. Eco. Heal. Env. 2014, 2: 1, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Carrim, A. J. I.; Barbosa, E. C.; Vieira, J. D. G. Enzymatic activity of endophytic bacterial isolates of Jacaranda decurrens Cham.(Carobinha-do-campo). Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 2006,49(3), 353-359. [CrossRef]

- Vinoth, R. S.; Kanikkai, R. A.; Babu, V. A.; Manoj, G. T.; Naman, H. S.; Johnson, A. J.; Infant, S. B.; Sathiyaseelan, K. Study of starch degrading bacteria from kitchen waste soil in the production of amylase by using paddy straw. Recent. res. sci. Technol. 2009, 1(1): 008–013.

- Sierra, G.A. A simple method for the detection of lypolytic activity of microorganisms and some observations on the influence of the contact between cells and fatty substrates. A. Van Leeuw. 1957, 28: 15-22.

- Kumar, S.; Karan, R.; Kapoor, S.; Singh, S. P.; & Khare, S. K. Screening and isolation of halophilic bacteria producing industrially important enzymes. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2012, 43, 1595-1603.

- Christensen, W.B. Urea decomposition as a means of differentiating proteus and paracolon cultures from each other and from Salmonella and Shigella types. J. Bacteriol. 1946, 52, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S. C., & Lockwood, J. Powdered chitin agar as a selective medium for enumeration of actinomycetes in water and soil. Applied microbiology. 1975, 29(3), 422-426. 29.

- Kopečný, J.; Hodrová, B.; Stewart, C.S. The isolation and characterization of a rumen chitinolytic bacterium. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1996, 23, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorck, H. Production of hydrocyanic acid by bacteria. Physiol. Plant. 1948, 1, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bric, J.M., Bostock, R.M.; Silverston, S.E. Rapid in situ assay for indole acetic acid production by bacteria immobilization on a nitrocellulose membrane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 535–538. 1991; 57, 535–538.

- Fokkema, N.J. Fungal antagonism in the phylosphere. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1978, 89, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagahón, I.P.; Reyes, M.A.A.; Rojas, H.V.S.; Cuenca, A.A.; Jurado, A.T.; Alvarez, I.O.C.; Flores, Y.M. Isolation of bacteria with antifungal activity against the phytopathogenic fungi Stenocarpella maydis and Stenocarpella macrospora. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 5522–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsten, L.; De Jager, E.S. Mode of action of Bacillus subtilis for control of avocado postharvest pathogens. S. Afr. Avocado Growers Assoc. Yearb. 1995, 18, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Hwang, B.K. Diversity of antifungal Actinomycetes in various vegetative soils of Korea. Can. J. Microbiol. 2002, 48, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. ; Ning, P.; Zheng, L.; Huang, J.; Li, G.; Hsiang, T. Fumigant activity of volatiles of Streptomyces globisporus JK-1 against Penicillium italicum on Citrus microcarpa. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010,58:157–165. [CrossRef]

- Aghighi, S.; Shahidi Bonjar, G.H.; Saadoun, I.; Rawashdeh, R.; Batayneh, S. First report of antifungal spectra of activity of Iranian actinomycetes strains against Alternaria solani, Alternaria alternata, Fusarium solani, Phytophthora megasperma, Verticillium dahliae and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2004, 3, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdieh, S.; Gholam, H.S.B.; Gholam, R.S.S. Post-harvest biological control of apple bitter rot by soil-borne Actinomycetes and molecular identification of the active antagonist. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 112, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C.; Webster, J. Antagonistic properties of species groups of Trichoderma, II. Production of volatile antibiotics. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1971, 57, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorjandi, M.; Shahidi Bonjar, G.H.; Baghizadeh, A.; Sharifi Sirchi, G.R.; Massumi, H.; Baniasadi, F.; Aghighi, S.; Rashid Farokhi, P. Biocontrol of Botrytis allii Munn the causal agent of neck rot, the post-harvest disease in onion, by use of a new Iranian Iisolate of Streptomyces. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2009, 4(1), 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.O.; Jeong, S.W.; Lee, C.Y. Antioxidant capacity of phenolic phytochem-icals from various cultivars from pulms. Food Chem. 2002, 81, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Guessan, A.H.O.; Dago Déliko, C.E.; Akhanovna, J.; Békro, M.; Békro, Y.A. Teneurs en composés phénoliques de 10 plantes médicinales employées dansla tradithérapie de l’hypertension artérielle, une pathologie émergente en Côted’Ivoire. Génie industriel. 2011, 6, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z-T. ; Li, R. Screening and evaluation of active compounds in polyphenol mixtures by HPLC coupled with chemical methodology and its application, Food Chemistry. 2017, 227, 187-193. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.L.; and Kim, Y.K. Postharvest fruit rots in apples caused by Botrytis cinerea, Phacidiopycnis washingtonensis, and Sphaeropsis pyriputrescens. Online. Plant Health Progress. 2008, 9(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Lu, H.; Wu, C.; Fang, W.; Yu, C.; Ye, C.; & al. Rhodosporidium paludigenum induces resistance and defense-related responses against Penicillium digitatum in citrus fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 85, 196–202. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Sun, C.C.; Guan, X.N.; Lian, S.; Li, B.; Wang, C. Butylated hydroxytoluene induced resistance against Botryosphaeria dothidea in apple fruit. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 599062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zihao, S.; Baihui H.; Cuicui, W.; Shiyu, L.; Yuxin, X.; Baohua, L.; and Caixia, W. Biocontrol features of Pseudomonas syringae B-1 against Botryosphaeria dothidea in apple fruit. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 11 : 599062. [CrossRef]

- Orhan, F. Alleviation of salt stress by halotolerant and halophilic plant growth-promoting bacteria in wheat (Triticum aestivum), Braz. J. Microbiol. 2016, 47, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensidhoum, L.; Nabti, E.H.; Tabli, N.; Kupferschmied, P.; Weiss, A.; Rothballer, M.; Schmid, M.; Keel, C.; Hartmann, A. Heavy metal tolerant Pseudomonas protegens isolates from agricultural well water in northeastern Algeria with plant growth promoting, insecticidal and antifungal activities, European Journal of Soil Biology. 2016, 75, 38-46. [CrossRef]

- Vimal, S.R.; Singh, J.S.; Arora, N.K.; Singh, D.P. PGPR-an effective bioagent in stress agriculture management. In: Sarma, B.K., Jain, A. (Eds.), Microbial Empowerment in Agriculture: A Key to Sustainability and Crop Productivity. Biotech Books, New Delhi), 2016, 1–108.

- Farahmand, N.; Sadeghi, V. Estimating soil salinity in the dried lake bed of urmia lake using optical sentinel-2 images and nonlinear regression models. J. Indian Soc. Rem. Sens. 2020, 48 (4), 675–687. April 2020. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; La, S.; Zhang, X.; Gao, L.; Tian, Y. Salt-induced recruitment of specific root-associated bacterial consortium capable of enhancing plant adaptability to salt stress. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2865–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djebaili, R.; Marika, P.; Claudia, E.; Beatrice, F.; Mahmoud, K.; and Maddalena, D.G. "Biocontrol of Soil-Borne Pathogens of Solanum lycopersicum L. and Daucus carota L. by Plant Growth-Promoting Actinomycetes: In Vitro and In Planta Antagonistic Activity" Pathogens. 2021, 10, 1305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Noumavo, P.A.; Agbodjato, N.A.; Baba-Moussa, F.; Adjanohoun, A.; Baba-Moussa, L. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria: Beneficial effects for healthy and sustainable agriculture. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 15(27):1452-1463.

- Tabli, N.; Rai, A.; Bensidhouma, L.; Palmierib, G.; Gogliettinob, M.; Coccab, E.; Consigliob, C.; Cilloc, F.; Bubicic, G. ; Nabti, El-H. Plant growth promoting and inducible antifungal activities of irrigation well water-bacteria. J. Biocontrol. 2017, 10.010.

- Desoky, E.S.M.; Saad, A M.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Merwad, A.R.M.; Rady, M.M. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: Potential improvement in antioxidant defense system and suppression of oxidative stress for alleviating salinity stress in Triticum aestivum (L.) plants. j.bcab. 2020, 30, 1878-8181. [CrossRef]

- Oliva, G.; Di Stasio, L.; Vigliotta, G.; Guarino, F.; Cicatelli, A.; Castiglione, S. Exploring the potential of four novel halotolerant bacterial strains as plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) under saline conditions. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.; Mitra, A.; Roy, M. Halomonas rhizobacteria of avicennia marina of indian sundarbans promote rice growth under saline and heavy metal stresses through exopolysaccharide production. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10:1207. [CrossRef]

- Alijani, Z.; Amini, J.; Karimi, K.; Pertot, I. Characterization of the Mechanism of action of Serratia rubidaea Mar61-01 against Botrytis cinerea in Strawberries. Plants. 2023, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamou, N.N.; Dubey, M.; Tzelepis, G.; Menexes, G.; Papadakis, E.N.; Karlsson, M.; agopodi, A.L.; Jensen, D.F. Investigating the compatibility of the biocontrol agent Clonostachys rosea IK726 with prodigiosin-producing Serratia rubidaea S55 and phenazineproducing Pseudomonas chlororaphis ToZa7. Arch. Microbiol. 2016, 198, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Huang, Y. Endophytic Bacterium Serratia plymuthica From Chinese Leek Suppressed Apple Ring Rot on Postharvest Apple Fruit. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12:802887. [CrossRef]

- Cherif, H.; Sghaier, I.; Hassen, W.H.; Amara, C.; Masmoudi, A.S.; Cherif, A.; Neifar, M. Halomonas desertis G11, Pseudomonas rhizophila S211 and Oceanobacillus iheyensis E9 as biological control agents against wheat fungal pathogens: PGPB consorcia optimization through mixture design and response surface analysis. Int Clin Pathol J. 2022, 9(1):20‒28.

- Fillinger, S.; Elad, Y. Botrytis - The Fungus, the Pathogen and Its Management in Agricultural Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland. 2016, 488.

- Xun, F.; Xie, B.; Liu, S.; Guo, C. Effect of plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPR) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) inoculation on oats in saline-alkali soil contaminated by petroleum to enhance phytoremediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-López, J.A.; Rangel-Vargas, E.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Villagómez-Ibarra, J.R.; Falfán-Cortes, R.N.; Acevedo-Sandoval, O.A.; Castro-Rosas, J. Isolation and Molecular Identification of Serratia Strains Producing Chitinases, Glucanases, Cellulases, and Prodigiosin and Determination of Their Antifungal Effect against Colletotrichum siamense and Alternaria alternata In Vitro and on Mango Fruit. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2022, 13, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, S.; Agha, S.I.; Jamil, N.; Tabassum, B.; Ahmed, S.; Raheem, A.; Jahan, N.; Ali, N.; Khan, A. Characterization and survival of broad-spectrum biocontrol agents against phytopathogenic fungi. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2022, 54(3), 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimtha, J.C.; Jishma, P.; Sreelekha, S.; Chithra, S.; Radhakrishnan, E. K. Antifungal properties of prodigiosin producing rhizospheric Serratia sp. Rhizosphere. 2017, 3, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorokhod, I.; &Kurdysh, I. The low-molecular weight antioxidants of microorganisms.Mikrobiology, 2014, 76: 48–59.

- Livinska, O.; Ivaschenko, O.; Garmasheva, I.; Kovalenko, N. The screening of lactic acid bacteria with antioxidant properties. Microbiology. 2016, 2(4), 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, S.C.; Verma, V.; Amna, T.; Qazi, G.N.; Spiteller, M. An endophytic fungus fromNothapodytes foetida that produces camptothecin. Journal of Natural Products. 2005, 68:1717–9.

- Garcia-Fraile, P.; Menéndez, E.; Rivas, R. Role of bacterial biofertilizers in agriculture and forestery. AIMS Bioengeneering. 2015, 2, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qurashi, A.W.; Sabri, A.N. Osmolyte accumulation inmoderately halophilic bacteria improves salt tolerance ofchickpea. Pak J Bot. 2013, 45:1011–1016.30.

- Essghaier, B.; Dhieb, C.; Rebib, H.; Ayari, S.; Boudabous, A.R.A.; Sadfi-Zouaoui, N. Antimicrobial behavior of intracellularproteins from two moderately halophilic bacteria: strain J31 of Terribacillus halophilus and strain M3-23 of Virgibacillusmarismortui. J Plant Pathol Microb. 2014, 5, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Bensidhoum, L.; Tabli, N.; Bouaoud, Y.; Naili, F.; Cruz, C.; Nabti, E. A Pseudomonas Protegens with high antifungal activity protects apple fruits against Botrytis Cinerea Gray Mold. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Tech. 2016, 2, 227–237.

- Masmoudi, F.; Abdelmaleka, N.; Tounsia, S.; Dunlapb, C.A.; Triguia, M. Abiotic stress resistance, plant growth promotion and antifungal potential of halotolerant bacteria from a Tunisian solar saltern. Microbiological Research. 2019, 229, 126331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiero, L.; Perrig, D.; Masciarelli, O.; Penna, C.; Cassan, F.; Luna, V. Phytohormone production by three strains of Bradyrhizobiumjaponicum and possible physiological and technologicalimplications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007,74:874–880.

- Desale, P.; Patel, B.; Singh, S.; Malhotra, A.; Nawani, N. Plantgrowth promoting properties of Halobacillus sp. and Halomonas sp. in presence of salinity and heavy metals. JBasic Microbiol. 2014, 54: 781–791.

- Duca, D.R. & Glick, B.R. Indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis and its regulation in plant-associated bacteria. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2020,104, 8607-8619. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. P.; & Jha, P. N. The multifarious PGPR Serratia marcescens CDP-13 augments induced systemic resistance and enhanced salinity tolerance of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLos one. 2016, 11(6), e0155026. [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Maheshwari, D.K. Use of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs) with multiple plant growth promoting traits in stress agriculture: Action mechanisms and future prospects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 156, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Tran, D.M.; Nguyen, T.T.M.; Hung, S.-H.; Huang, E.; Huang, C.-C. Roles of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) in stimulating salinity stress defense in plants: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijani, Z.; Amini, J.; Ashengroph, M. et al. Antifungal Activity of Serratia rubidaea Mar61-01 Purified Prodigiosin Against Colletotrichum nymphaeae, the Causal Agent of Strawberry Anthracnose. J Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 585–595. [CrossRef]

- Vacheron, J.; Desbrosses, G.; Bouffaud, M.L.; Touraine, B.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; Muller, D.; Prigent-Combaret, C. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and root system functioning. Frontiers in plant science. 2013, 4, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Asadullah, Imran, A.; Marghoob, M.U.; Imtiaz, M.; Mubeen, F. Potential of Salt Tolerant PGPR in Growth and Yield Augmentation of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Under Saline Conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11:2019.

| SB6 | CH11 | CH12 | SB29 | SB39 | CH42 | |

| Cellulase Amylase Lipase Protease Urease Chitinase Nitrogen fixation Phosphate solubilization IAA (µg/mL) NH3 HCN |

+ +++ - +++ - +++ + ++ - ++ + |

+ - ++ +++ - +++ + ++ - + - |

++ - - +++ + +++ + - - + - |

- - ++ +++ - +++ ++ + - ++ - |

+ +++ - +++ ++ ++ ++ - +++ +++ |

+ - + - ++ ++ ++ - ++ - |

| RRT(min) | Coumpound name | Broth filtrate (mg/ml) | |||||

| SB6 - | CH11 - | CH11 + | CH11 dep | SB39 + | SB39 dep | ||

| 3,15 ± 0,05 | Gallic acid | 13,77 | 20,79 | 12,76 | 13,43 | 21,56 | 9,53 |

| 3,61 ± 0,00 | Hydroxy quinone | - | - | - | - | 6,31 | - |

| 5,47 ± 0,23 | Resorcinol | 2,24 | 2,82 | 2,29 | 2,88 | 5,38 | - |

| 6,10 ± 0,17 | Catechin | 3,81 | 4,84 | 4,27 | 1,29 | 5,17 | 3,50 |

| 6,23 ± 0,41 | 1,2-hydroxy benzen | - | 8,16 | 3,13 | 3,55 | - | - |

| 7,21 ± 0,05 | Syringic acid | 16,65 | 13,24 | 18,54 | 11,72 | 22,88 | 12,23 |

| 10,63 ± 0,00 | Naringenin-7-glucoside | - | - | 4,56 | - | - | - |

| 11,08 ± 0,00 | 3,4,5-Trimethoxy benzoic acid | 2,51 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11,36 ± 0,01 | m-anisic acid | - | 1,82 | 1,01 | 2,39 | - | - |

| 15,07 ±0,01 | Hesperidine | 9,69 | 1,91 | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).