Submitted:

06 February 2024

Posted:

06 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

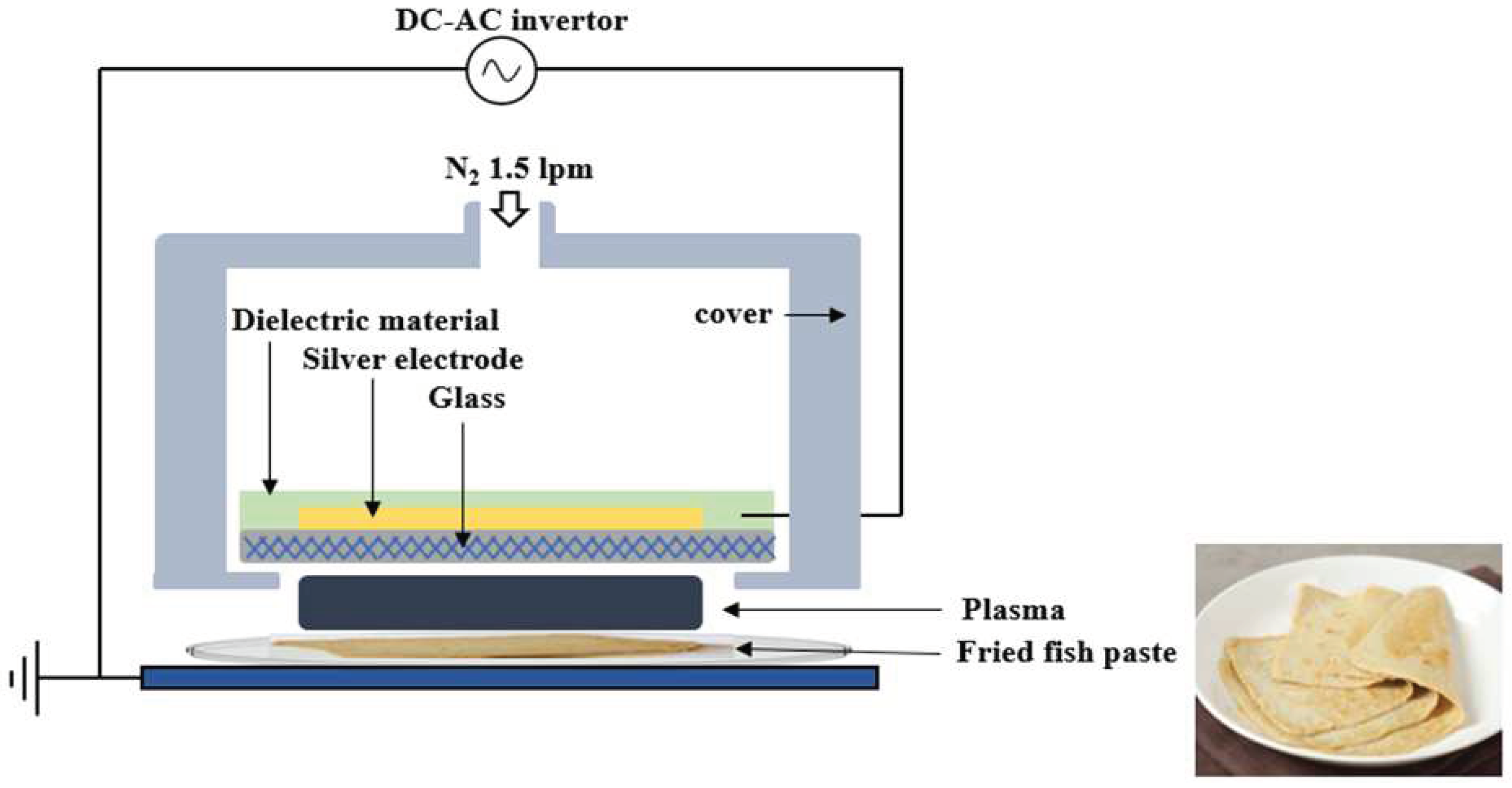

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample preparation and bacteria inoculation

2.2. Sample preparation and bacteria inoculation

2.3. Quantification of bacterial analysis

2.4. Modeling of decimal reduction times

- N0 is the initial microbial population (CFU/g)

- N is the microbial population by FE-DBD plasma treatment time (CFU/g)

- t is the FE-DBD plasma treatment time (min)

- k is the reduction rate constant

- Nt is the number of microorganism (log CFU/g) after the FE-DBD plasma treatment time t

- N0 is the initial microbial population (log CFU/g)

- t is the FE-DBD plasma treatment time (min)

- b is indicating the time needed to reduce the population for one log unit

- n (parameter) is indicating the shape of the survival curve

2.5. Physicochemical quality evaluation [pH value, VBN]

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results

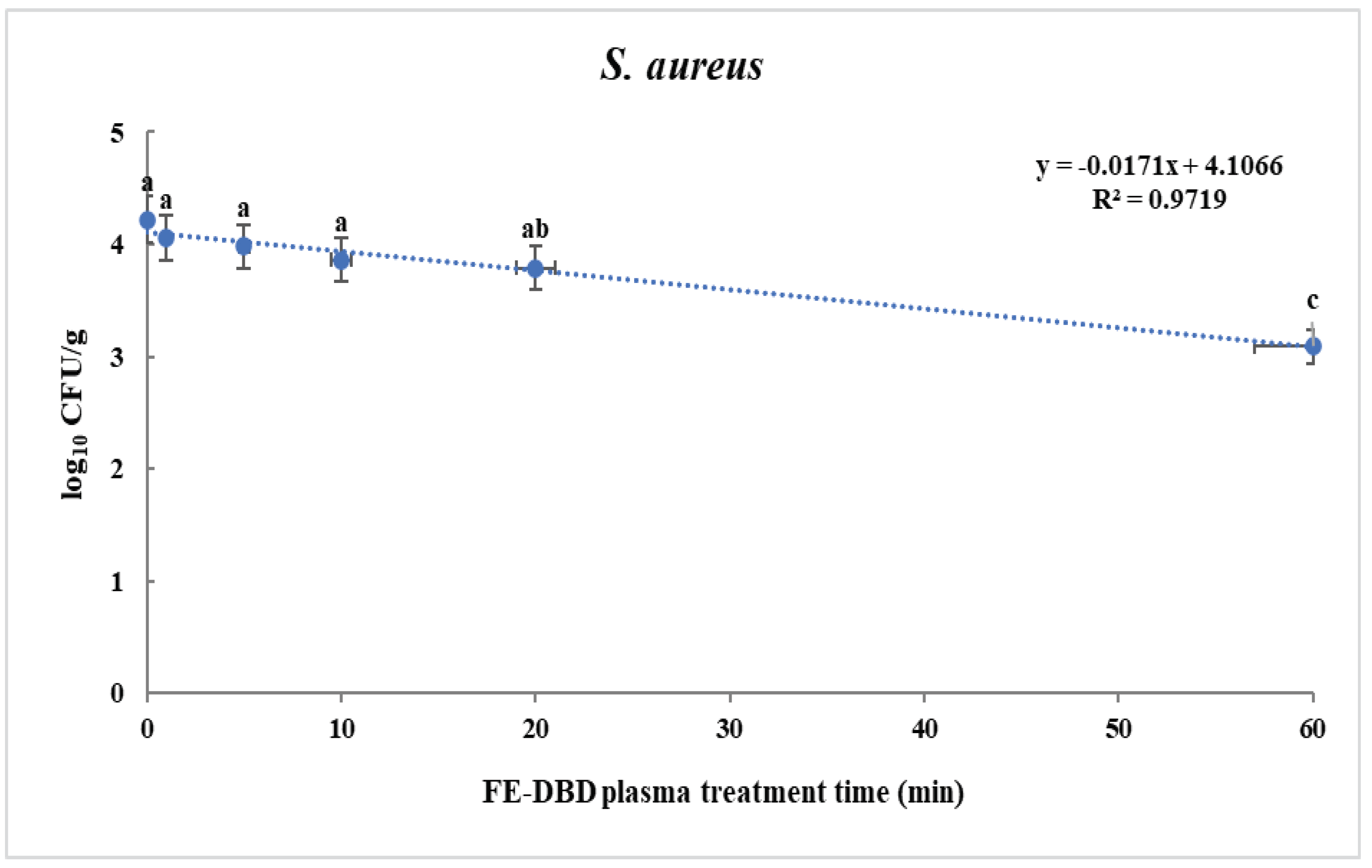

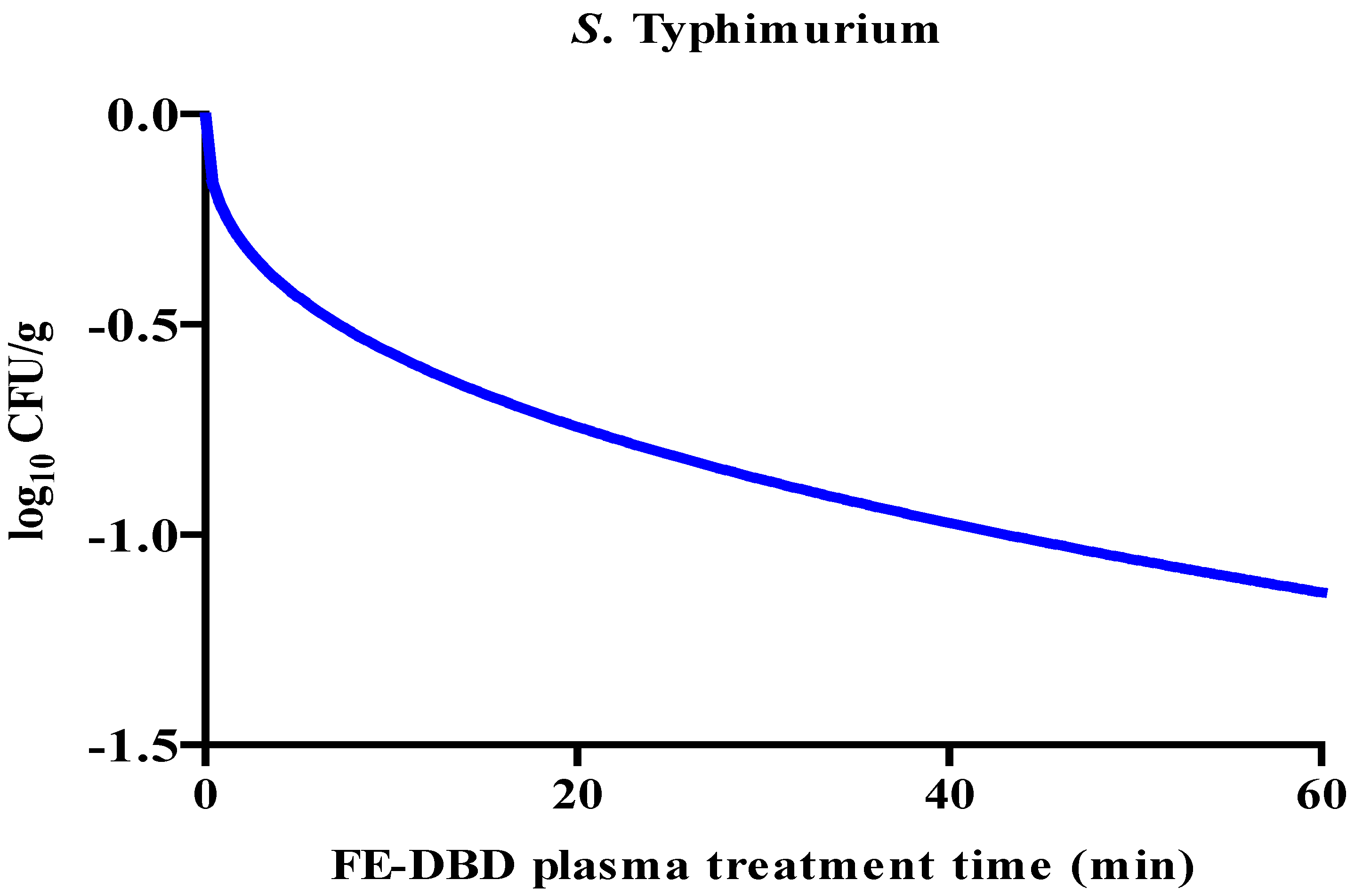

3.1. Reduction and D-value of S. aureus and S. Typhimurium in fried fish paste after FE-DBD plasma treatment

3.2. Quality (pH and VBN) of fried fish paste after FE-DBD plasma treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shin, H.Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, I.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Oh, S.J.; Song, K.B. Effect of chlorine dioxide treatment on microbial growth and qualities of fish paste during storage. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biolo. Chem. 2007, 50, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, K.M.I.; Kim, J.S.; An, J.H.; Sohn, J.H.; Choi, J.S. Natural food additives and preservatives for fish-paste products: A review of the past, present, and future states of research. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.S.; Choi, N.D.; Lee, S.Y. Food quality and shelf-life of Korean commercial fried Kamaboko. Korean J Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 47, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jeon, J.Y.; Ryu, S.R.; Kim, Y.J.; Suh, C.S.; Lee, J.W.; Byun, M.W. Microbial quality and physiochemical changes of grilled fish paste in a group-meal service affected by gamma-irradiation. Korean J. Food Preserv. 2004, 11, 522–529. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.H.; Ra, C.H.; Kim, S.H.; Shon, H.W.; Chung, H.Y. Effects of bactocease treatment on microbial growth and quality of fried fish paste during storage. Food Eng. Prog. 2022, 26, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Cho, M.L.; Heu, M.S. Quality improvement of heart-induced surimi gel using calcium powder of cuttle, Sepia esculenta bone treated with acetic acid. J. Kor. Fish, Soc. 2003, 36, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butscher, D.; Van Loon, H.; Waskow, A.; von Rohr, P.R.; Schuppler, M. Plasma inactivation of microorganisms on sprout seeds in a dielectric barrier discharge. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 238, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Liu, D.; Xiang, Q.; Ahn, J.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Ding, T. Inactivation mechanisms of non-thermal plasma on microbes: A review. Food Control 2017, 75, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, D.B. The emerging role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in redox biology and some implications for plasma applications to medicine and biology. J. Phys. D.: Appl. Phys. 2012, 45, 263001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, E.B.; Choi, M.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, E.H.; Lim, J.S.; Choi, J.S.; Ha, K.S.; Kwon, J.Y.; Jeong, S.H.; Park, S.Y. Assessment of potential infectivity of human norovirus in the traditional Korean salted clam product “Jogaejeotgal” by floating electrode-dielectric barrier discharge plasma. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, B.H.; Al-Shammari, A.M.; Murbat, H.H. Breast cancer treatment using cold atmospheric plasma generated by the FE-DBD scheme. Clin. Plasma Med. 2020, 19, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svarnas, P.; Giannakopoulos, E.; Kalavrouziotis, I.; Krontiras, C.; Georga, S.; Pasolari, R.S.; Papadopoulos, P.K.; Apostolou, I.; Chrysochoou, D. Sanitary effect of FE-DBD cold plasma in ambient air on sewage biosolids. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, C J. ; Kim C.K. Atmospheric pressure floating electrode-dielectric barrier discharge (FE-DBDs) having flexible electrodes. Korean J Chem. Eng. Res. 2019, 57, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arserim, E.H.; Salvi, D.; Fridman, G.; Schaffner, D. W.; Karwe, M.V. Microbial inactivation by non-equilibrium short-pulsed atmospheric pressure dielectric barrier discharge (cold plasma): Numerical and experimental studies. Food Eng. Rev. 2021, 13, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.; Fridman, G.; Fridman, A.; Joshi, S.G. Biological responses of Bacillus stratosphericus to floating electrode-dielectric barrier discharge plasma treatment. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 2039–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.G.; Paff, M.; Friedman, G.; Fridman, G.; Fridman, A.; Brooks, A.D. Control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in planktonic form and biofilms: A biocidal efficacy study of non-thermal DBD plasma. Am. J. Infect. Control 2010, 38, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Standard for Food. 2022. Available online: http://various.foodsafetykorea.go.kr/fsd/#/ext/Document/FC (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Buzrul, S.; Alpas, H. Modeling inactivation kinetics of food borne pathogens at a constant temperature. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.S.; Kim, K.H. An evaluation of the physicochemical properties of salted and fermented shrimp for HACPP. J. East Asian Soc. Diet. Life. 2009, 19, 395–400. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, S.Z.; Chen, J.Y.; Chen, D.Z.; Deng, S.G.; Xu, B. Effect of cold plasma on maintaining the quality of chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus): biochemical and sensory attributes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 99, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, S.; Moslehishad, M.; Dejam, L. Effect of atmospheric pressure floating-electrode dielectric-barrier discharge (FE-DBD) plasma on microbiological and chemical properties of Nigella sativa L. J. Bas. Res. Med. Sci. 2020, 7, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.K.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, M.H. Quality characteristics of fried fish paste added with ethanol extract of onion. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 33, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.P.; Kim, B.; Choe, J.H.; Jung, S.; Moon, S.Y.; Choe, W.H.; Jo, C.R. Evaluation of atmospheric pressure plasma to improve the safety of sliced cheese and ham inoculated by 3-strain cocktail Listeria monocytogenes. Food Microbiol. 2009, 26, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, J.; Homma, T.; Osaki, T. Superoxide radicals in the execution of cell death. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Patil, S.; Keener, K.M.; Cullen, P.J.; Bourke, P. Bacterial inactivation by high-voltage atmospheric cold plasma: influence of process parameters and effects on cell leakage and DNA. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.S.; Tiede, R.; Gavenis, K.; Daeschlein, G.; Bussiahn, R.; Weltmann, K.D.; Emmert, S.; Woedtke, T.V.; Ahmed, R. Introduction to DIN-specification 91315 based on the characterization of the plasma jet kINPen® MED. Clin. Plasma Med. 2016, 4, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.S.; Jeon, E.B.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, E.H.; Lim, J.S.; Choi, J.S.; Park, S. Y. Impact of non-thermal dielectric barrier discharge plasma on Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus and quality of dried blackmouth angler (Lophiomus setigerus). J. Food Eng. 2020, 278, 109952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Kang, S.J.; Ha, S.D. Inactivation of murine norovirus-1 in the edible seaweeds Capsosiphon fulvescens and Hizikia fusiforme using gamma radiation. Food Microbiol. 2016, 56, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calsolari, A. Microbial death. In Physiological Models in Microbiology; CRC press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2018; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Buzrul, S. The Weibull model for microbial inactivation. Food Eng. Rev. 2022, 14, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, Z.A.; Rezai, M.; Hosseini, S.V.; Regenstein, J.M.; Boehme, K.; Alishahi, A.; Yadollahi, F. Chilled storage of golden gray mullet (Liza aurata). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 1894–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.F.; Cheng, Y.; Ye, J. X.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, J.; Yang, S.P. Targeting shrimp spoiler Shewanella putrefaciens: Application of ε-polylysine and oregano essential oil in Pacific white shrimp preservation. Food Control 2021, 123, 107702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Su, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, S.; Hu, Y.; Ye, X.; Wang, J.; Ding, T. Application of atmospheric cold plasma-activated water (PAW) ice for preservation of shrimps (Metapenaeus ensis). Food Control 2018, 94, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microorganism | FE-DBD plasma treatment (min) |

Mean±SD (log10 CFU/g) |

Log reduction (log10 CFU/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | 0 | 4.22±0.42a | - |

| 1 | 4.06±0.26a | 0.16±0.26B | |

| 5 | 3.98±0.20a | 0.24±0.2B | |

| 10 | 3.86±0.13a | 0.36±0.13B | |

| 20 | 3.79±0.10ab | 0.43±0.1B | |

| 30 | 3.36±0.33bc | 0.86±0.33A | |

| 60 | 3.09±0.13c | 1.13±0.13A | |

| S. Typhimurium | 0 | 4.09±0.24a | - |

| 1 | 3.84±0.22a | 0.25±0.22C | |

| 5 | 3.74±0.25ab | 0.35±0.25BC | |

| 10 | 3.32±0.26bc | 0.77±0.26AB | |

| 20 | 3.26±0.16c | 0.83±0.16A | |

| 30 | 3.24±0.23c | 0.85±0.23A | |

| 60 | 2.96±0.35c | 1.13±0.35A |

| Microorganism | Model Parameters | R2 | D-value ± SD (min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | Decay slope | 0.018 | 0.97 | 58.92±1.63a |

| S. Typhimurium | b±SD | 0.233±0.025 | 0.97 | 43.60±0.76b |

| n±SD | 0.387±0.030 | |||

| FE-DBD plasma treatment (min) | pH | VBN (mg/%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 5.37±0.01NS | 8.15±1.67a |

| 1 | 5.37±0.02 | 8.12±0.07a |

| 5 | 5.37±0.02 | 7.49±2.44a |

| 10 | 5.37±0.01 | 6.98±1.58ab |

| 20 | 5.37±0.02 | 4.71±1.65bc |

| 30 | 5.37±0.01 | 3.48±0.01c |

| 60 | 5.37±0.00 | 3.46±0.00c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).