Submitted:

01 February 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Bacteriological Culture Results

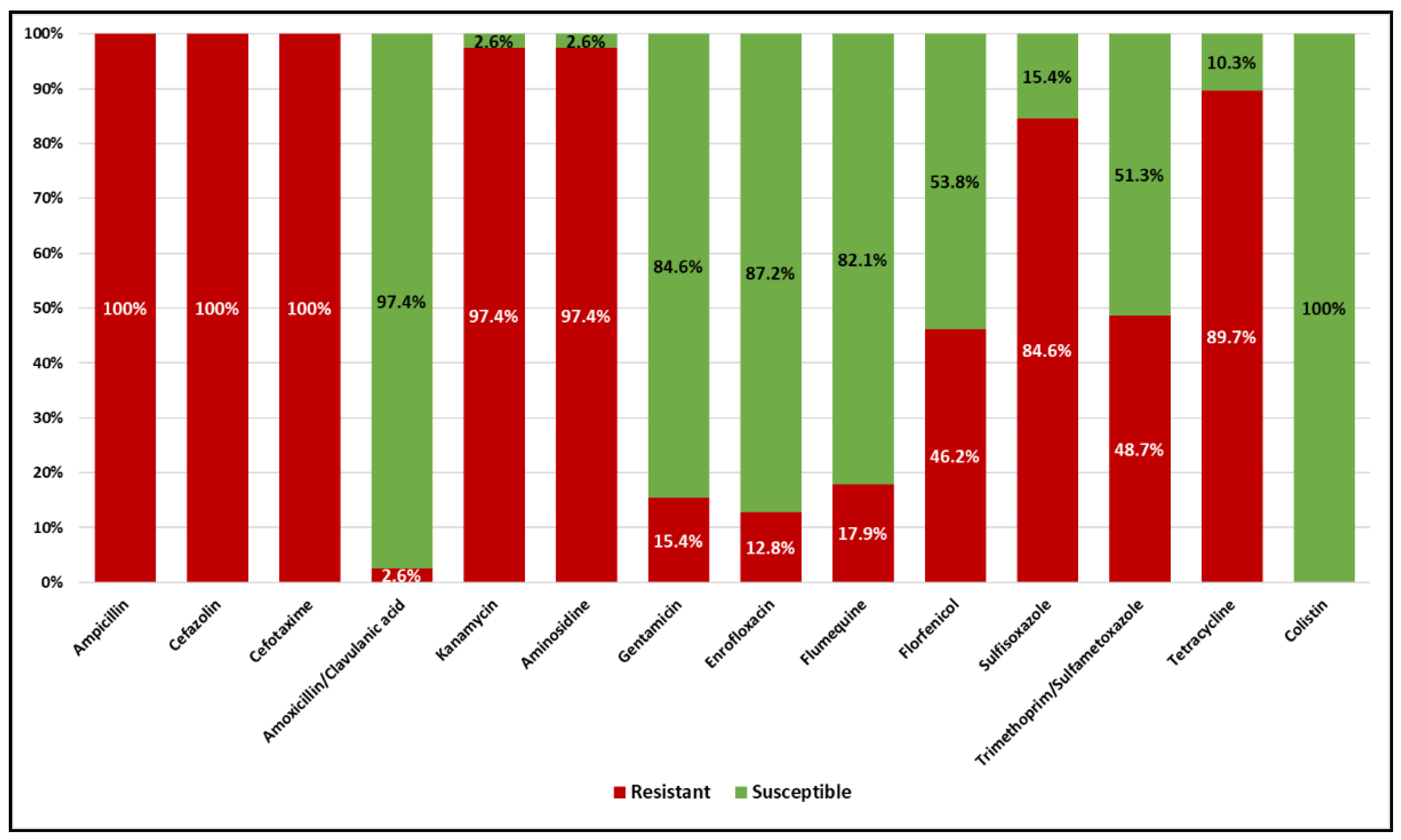

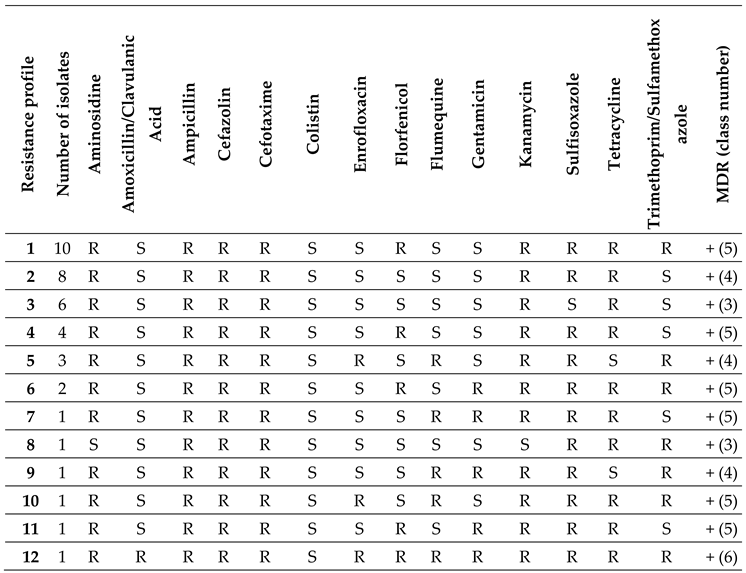

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of ESBL E. coli

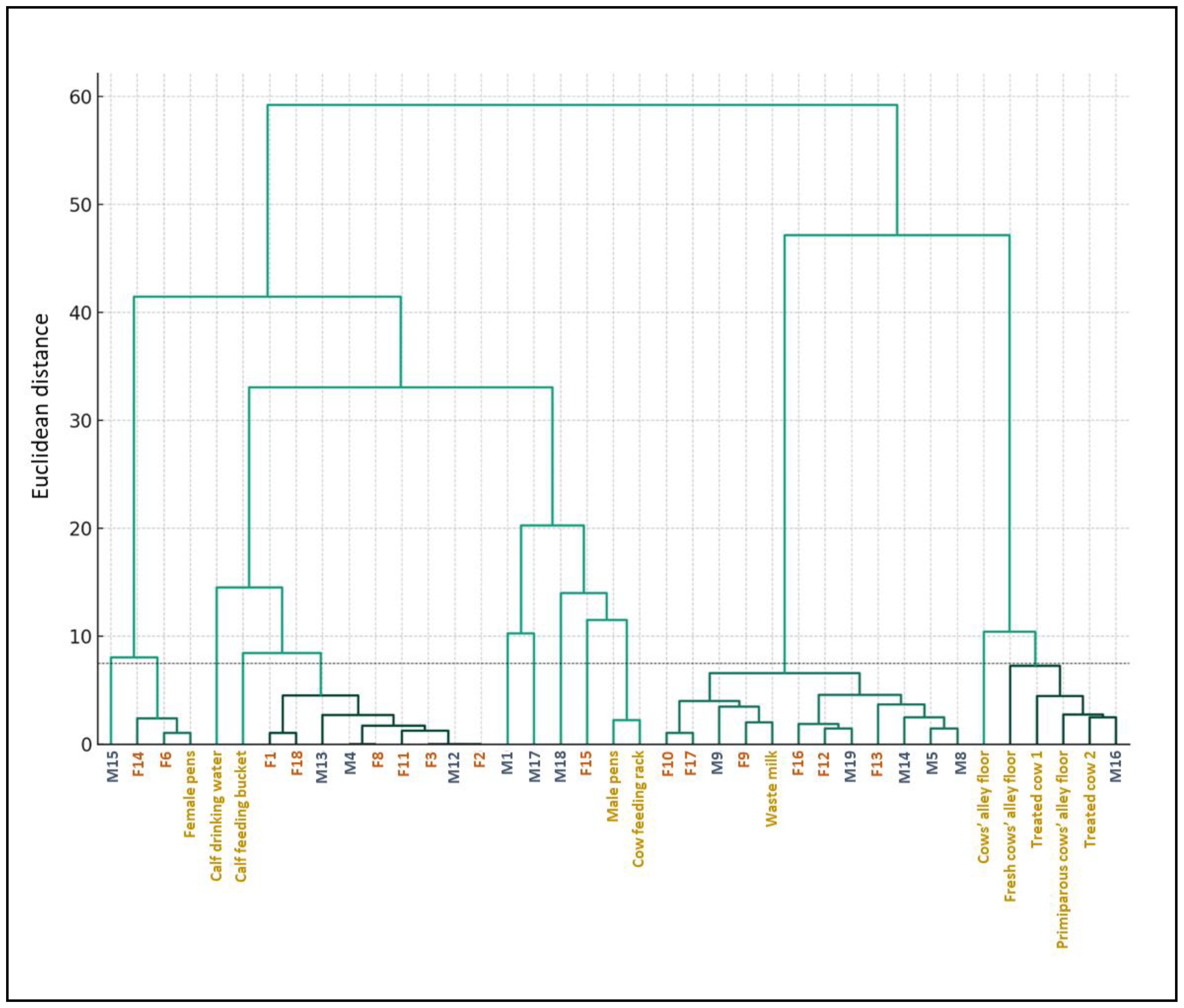

2.3. Hierarchical Clustering of E. coli Isolates Based on the MIC Results

2.4. Results of the Biosecurity Questionnaire

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

2.1. Farm Description and Ethics Statement

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Animals and Sample Collection

2.4. ESBL E. coli Isolation and Characterization

2.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.6. Hierarchical Clustering

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-europe-2022-2020-data (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240062702 (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Ma, Z.; Lee, S.; Jeong, K.C. Mitigating Antibiotic Resistance at the Livestock-Environment Interface: A Review. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2019, 29, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Medicine Agency (EMA). Third Joint Inter-Agency Report on Integrated Analysis of Consumption of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria from Humans and Food-Producing Animals in the EU/EEA. EFSA Journal 2021, 19, e06712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, N.V.; Padungtod, P.; Thwaites, G.; Carrique-Mas, J.J. Antimicrobial Usage in Animal Production: A Review of the Literature with a Focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Antibiotics (Basel) 2018, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, K.; Fisher, J.F. Epidemiological Expansion, Structural Studies, and Clinical Challenges of New β-Lactamases from Gram-Negative Bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 2011, 65, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, S.; Fatima, J.; Shakil, S.; Rizvi, S.M.D.; Kamal, M.A. Antibiotic Resistance and Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamases: Types, Epidemiology and Treatment. Saudi J Biol Sci 2015, 22, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reygaert, W.C. An Overview of the Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms of Bacteria. AIMS Microbiol 2018, 4, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetens, J.L.; Billerbeck, S.; Schwenker, J.A.; Hölzel, C.S. Short Communication: Selection of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia Coli in Dairy Calves Associated with Antibiotic Dry Cow Therapy-A Cohort Study. J Dairy Sci 2019, 102, 11449–11452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massé, J.; Lardé, H.; Fairbrother, J.M.; Roy, J.-P.; Francoz, D.; Dufour, S.; Archambault, M. Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance and Characteristics of Escherichia Coli Isolates From Fecal and Manure Pit Samples on Dairy Farms in the Province of Québec, Canada. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 654125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Jackson, C.R.; Frye, J.G. Freshwater Environment as a Reservoir of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Appl Microbiol 2023, 134, lxad034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrazeg, M.; Drissi, M.; Medjahed, L.; Rolain, J.M. Hierarchical Clustering as a Rapid Tool for Surveillance of Emerging Antibiotic-Resistance Phenotypes in Klebsiella Pneumoniae Strains. J Med Microbiol 2013, 62, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duse, A.; Waller, K.P.; Emanuelson, U.; Unnerstad, H.E.; Persson, Y.; Bengtsson, B. Risk Factors for Antimicrobial Resistance in Fecal Escherichia Coli from Preweaned Dairy Calves. J Dairy Sci 2015, 98, 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homeier-Bachmann, T.; Kleist, J.F.; Schütz, A.K.; Bachmann, L. Distribution of ESBL/AmpC-Escherichia Coli on a Dairy Farm. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, L.P.; Dreyer, S.; Heppelmann, M.; Schaufler, K.; Homeier-Bachmann, T.; Bachmann, L. Prevalence and Risk Factors for ESBL/AmpC-E. Coli in Pre-Weaned Dairy Calves on Dairy Farms in Germany. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ); Ricci, A.; Allende, A.; Bolton, D.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; Fernández Escámez, P.S.; Girones, R.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Lindqvist, R.; et al. Risk for the Development of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Due to Feeding of Calves with Milk Containing Residues of Antibiotics. EFSA Journal 2017, 15, e04665. [CrossRef]

- Elizondo-Salazar, J.; Jones, C.; Heinrichs, A. Evaluation of Calf Milk Pasteurization Systems on 6 Pennsylvania Dairy Farms. Journal of dairy science 2010, 93, 5509–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ); Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; de Cesare, A.; Hilbert, F.; Lindqvist, R.; et al. Update of the List of Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) Recommended Microorganisms Intentionally Added to Food or Feed as Notified to EFSA. EFSA Journal 2023, 21, e07747. [CrossRef]

- Munns, K.D.; Selinger, L.B.; Stanford, K.; Guan, L.; Callaway, T.R.; McAllister, T.A. Perspectives on Super-Shedding of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 by Cattle. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2015, 12, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonggrijp, M.A.; Santman-Berends, I.M.G.A.; Heuvelink, A.E.; Buter, G.J.; van Schaik, G.; Hage, J.J.; Lam, T.J.G.M. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase- and AmpC-Producing Escherichia Coli in Dairy Farms. J Dairy Sci 2016, 99, 9001–9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, D.R.; Dodd, C.E.R.; Stekel, D.J.; Meshioye, R.T.; Diggle, M.; Lister, M.; Hobman, J.L. Multidrug-Resistant ESBL-Producing E. coli in Clinical Samples from the UK. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/categorisation-antibiotics-used-animals-promotes-responsible-use-protect-public-and-animal-health (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Waade, J.; Seibt, U.; Honscha, W.; Rachidi, F.; Starke, A.; Speck, S.; Truyen, U. Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacteria in Newborn Dairy Calves in Germany. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0248291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.M.A.; Abd-Elhafeez, H.H.; Al-Jabr, O.A.; El-Zamkan, M.A. Characterization of Acinetobacter Baumannii Isolated from Raw Milk. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucali, M.; Bava, L.; Tamburini, A.; Brasca, M.; Vanoni, L.; Sandrucci, A. Effects of Season, Milking Routine and Cow Cleanliness on Bacterial and Somatic Cell Counts of Bulk Tank Milk. J Dairy Res 2011, 78, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biocheck.UGent. Available online: https://biocheckgent.com/en (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Santman-Berends, I.M.G.A.; Gonggrijp, M.A.; Hage, J.J.; Heuvelink, A.E.; Velthuis, A.; Lam, T.J.G.M.; van Schaik, G. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase or AmpC-Producing Escherichia Coli in Organic Dairy Herds in the Netherlands. J Dairy Sci 2017, 100, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, N.M.; Penati, M.; Fusar-Poli, S.; Addis, M.F.; Tola, S. Species Identification by MALDI-TOF MS and Gap PCR–RFLP of Non-Aureus Staphylococcus, Mammaliicoccus, and Streptococcus Spp. Associated with Sheep and Goat Mastitis. Veterinary Research 2022, 53, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Available online: https://clsi.org/ (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Diluition Susceptibility Tests fro Bacteria Isolated from Animals, 4th ed.; Publisher: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); Methods for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria Isolated From Animals, 1st ed.; Publisher: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 29th ed.; Publisher: Wayne, PA, USA, 2019.

- Clinical Breakpoints and Dosing of Antibiotics (EUCAST). Available online: https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Comité de l’antibiogramme de la Société Francaise de Microbiologie (CASFM). Available online: https://www.sfm-microbiologie.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/CASFM_VET2018.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Ward Jr., J. H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample type | N | ESBL E. coli (%) | Negative (%) | ESBL A. baumannii (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female calf feces | 18 | 15 (83.3%) | 3 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Male calf feces | 19 | 13 (68.4%) | 6 (31.6%) | 0 |

| Treated cow feces | 3 | 2 (66%) | 1 (33%) | 0 |

| Dam feces | 26 | 0 | 26 (100%) | 0 |

| Waste milk | 1 | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Male calf pens | 1 | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Female calf pens | 1 | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed-use calf pens | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100%) |

| Calf feeding bucket | 2 | 1 (50%) | 0 | 1 (50%) |

| Calf drinking water | 2 | 1 (50%) | 0 | 1 (50%) |

| Cow alleys | 3 | 3 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Cow’s berth tube | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100%) |

| Cow water trough | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100%) |

| Cow feeding rack | 2 | 1 (50%) | 0 | 1 (50%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).