Submitted:

01 February 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

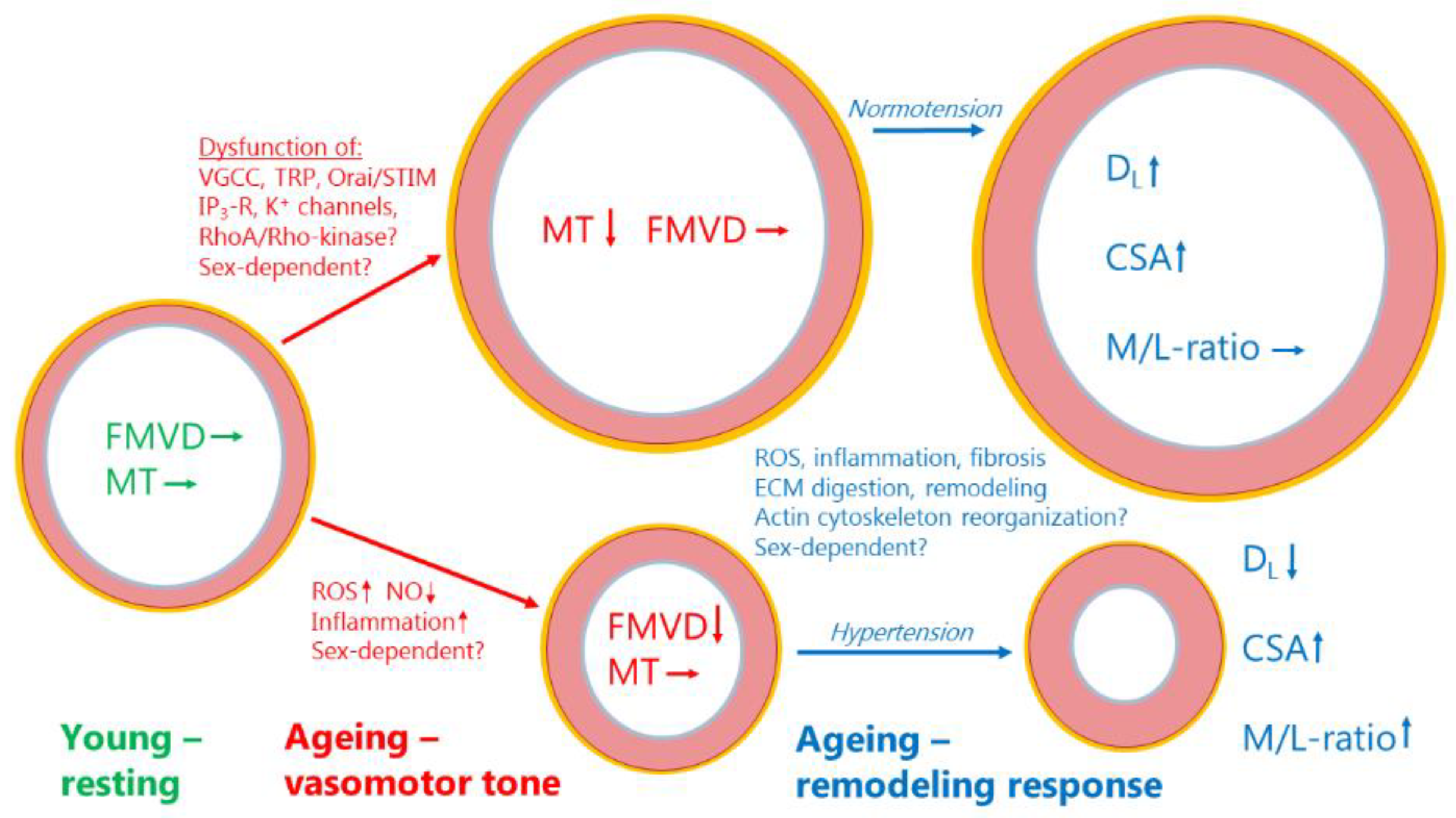

Systolic hypertension in ageing

Increased Mean Arterial Pressure in ageing

Myogenic response protects the microcirculation, but may be disrupted in ageing

Molecular determinants of reduced myogenic tone in aging?

Voltage-gated calcium channels

TRP channels

Intracellular calcium handling proteins

Potassium channels

RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway

Flow-mediated vasodilatation—indicator of endothelial (dys-)function in ageing

Resistance artery remodeling—a hypertrophic response to ageing

Potential molecular mechanisms in age-dependent structural remodeling

Protein-Protein interactions and pathway analysis of age-dependent mechanisms

Discussion and concluding remarks

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Schiffrin, E.L. How Structure, Mechanics, and Function of the Vasculature Contribute to Blood Pressure Elevation in Hypertension. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smulyan, H.; Mookherjee, S.; Safar, M.E. The two faces of hypertension: role of aortic stiffness. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2016, 10, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P. Arterial Stiffness and Hypertension in the Elderly. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020, 7, 544302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzoni, D.; Rizzoni, M.; Nardin, M.; Chiarini, G.; Agabiti-Rosei, C.; Aggiusti, C.; Paini, A.; Salvetti, M.; Muiesan, M.L. Vascular Aging and Disease of the Small Vessels. High Blood Press Cardiovasc. Prev 2019, 26, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorin-Trescases, N.; de Montgolfier, O.; Pincon, A.; Raignault, A.; Caland, L.; Labbe, P.; Thorin, E. Impact of pulse pressure on cerebrovascular events leading to age-related cognitive decline. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 314, H1214–H1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, S.; Agabiti-Rosei, C.; Bruno, R.M.; Rizzoni, D. Microcirculation and Macrocirculation in Hypertension: A Dangerous Cross-Link? Hypertension 2022, 79, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Gong, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Kong, W. Vascular Extracellular Matrix Remodeling and Hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal 2021, 34, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonck, E.; Feigl, G.G.; Fasel, J.; Sage, D.; Unser, M.; Rufenacht, D.A.; Stergiopulos, N. Effect of aging on elastin functionality in human cerebral arteries. Stroke 2009, 40, 2552–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagenseil, J.E.; Mecham, R.P. Vascular extracellular matrix and arterial mechanics. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 957–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huveneers, S.; Daemen, M.J.; Hordijk, P.L. Between Rho(k) and a hard place: the relation between vessel wall stiffness, endothelial contractility, and cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacolley, P.; Regnault, V.; Segers, P.; Laurent, S. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Arterial Stiffening: Relevance in Development, Aging, and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 1555–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacolley, P.; Regnault, V.; Laurent, S. Mechanisms of Arterial Stiffening: From Mechanotransduction to Epigenetics. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, S.S.; Gustin, W.t.; Wong, N.D.; Larson, M.G.; Weber, M.A.; Kannel, W.B.; Levy, D. Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1997, 96, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Xanthakis, V.; Sullivan, L.M.; Vasan, R.S. Blood pressure tracking over the adult life course: patterns and correlates in the Framingham heart study. Hypertension 2012, 60, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Kim, A.; Ebinger, J.E.; Niiranen, T.J.; Claggett, B.L.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; Cheng, S. Sex Differences in Blood Pressure Trajectories Over the Life Course. JAMA Cardiol 2020, 5, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harraz, O.F.; Jensen, L.J. Vascular calcium signalling and ageing. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 5361–5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flurkey, K.; Currer, J.M.; Harteneck, C. Mouse Models in Aging Research. In The Mouse in Biomedical Research: Normative Biology, Husbandry, and Models, 2nd ed.; Fox, J.G., Barthold, S.W., Davisson, M.T., Newcomer, C.E., Quimby, F.W., Smith, A.L., Eds.; Academic Press: Burlington, MA, 2007; pp. 637–672. [Google Scholar]

- Harraz, O.F.; Jensen, L.J. Aging, calcium channel signaling and vascular tone. Mech. Ageing Dev 2020, 191, 111336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, A.; Wang, S.; Takefuji, M.; Tang, C.; Althoff, T.F.; Schweda, F.; Wettschureck, N.; Offermanns, S. Age-dependent blood pressure elevation is due to increased vascular smooth muscle tone mediated by G-protein signalling. Cardiovasc. Res 2016, 109, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsha, G.; Denton, K.M.; Mirabito Colafella, K.M. Sex- and age-related differences in arterial pressure and albuminuria in mice. Biol. Sex Differ. 2016, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsha, G.; Mirabito Colafella, K.M.; Walton, S.L.; Gaspari, T.A.; Spizzo, I.; Pinar, A.A.; Hilliard Krause, L.M.; Widdop, R.E.; Samuel, C.S.; Denton, K.M. In Aged Females, the Enhanced Pressor Response to Angiotensin II Is Attenuated By Estrogen Replacement via an Angiotensin Type 2 Receptor-Mediated Mechanism. Hypertension 2021, 78, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.J.; Nielsen, M.S.; Salomonsson, M.; Sorensen, C.M. T-type Ca(2+) channels and autoregulation of local blood flow. Channels (Austin) 2017, 11, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmberg, J.; Bhattachariya, A.; Alajbegovic, A.; Rippe, C.; Ekman, M.; Dahan, D.; Hien, T.T.; Boettger, T.; Braun, T.; Sward, K.; et al. Loss of Vascular Myogenic Tone in miR-143/145 Knockout Mice Is Associated With Hypertension-Induced Vascular Lesions in Small Mesenteric Arteries. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorin-Trescases, N.; Bartolotta, T.; Hyman, N.; Penar, P.L.; Walters, C.L.; Bevan, R.D.; Bevan, J.A. Diameter dependence of myogenic tone of human pial arteries. Possible relation to distensibility. Stroke 1997, 28, 2486–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyborg, N.C.; Nielsen, P.J. The level of spontaneous myogenic tone in isolated human posterior ciliary arteries decreases with age. Exp. Eye Res. 1990, 51, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springo, Z.; Toth, P.; Tarantini, S.; Ashpole, N.M.; Tucsek, Z.; Sonntag, W.E.; Csiszar, A.; Koller, A.; Ungvari, Z.I. Aging impairs myogenic adaptation to pulsatile pressure in mouse cerebral arteries. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 2015, 35, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, P.; Csiszar, A.; Tucsek, Z.; Sosnowska, D.; Gautam, T.; Koller, A.; Schwartzman, M.L.; Sonntag, W.E.; Ungvari, Z. Role of 20-HETE, TRPC channels, and BKCa in dysregulation of pressure-induced Ca2+ signaling and myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries in aged hypertensive mice. Am. J. Physiol Heart Circ. Physiol 2013, 305, H1698–H1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, P.; Tucsek, Z.; Sosnowska, D.; Gautam, T.; Mitschelen, M.; Tarantini, S.; Deak, F.; Koller, A.; Sonntag, W.E.; Csiszar, A.; Ungvari, Z. Age-related autoregulatory dysfunction and cerebromicrovascular injury in mice with angiotensin II-induced hypertension. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013, 33, 1732–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geary, G.G.; Buchholz, J.N. Selected contribution: Effects of aging on cerebrovascular tone and [Ca2+]i. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2003, 95, 1746–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polk, F.D.; Hakim, M.A.; Silva, J.F.; Behringer, E.J.; Pires, P.W. Endothelial K(IR)2 channel dysfunction in aged cerebral parenchymal arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.T.; Pareek, T.; Sriramula, S.; Pabbidi, M.R. Aging influences cerebrovascular myogenic reactivity and BK channel function in a sex-specific manner. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1372–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, S.; Qu, L.; Wang, L.; Buggs, J.; Tan, X.; Cheng, F.; Liu, R. Aging Impairs Renal Autoregulation in Mice. Hypertension 2020, 75, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller-Delp, J.; Spier, S.A.; Ramsey, M.W.; Lesniewski, L.A.; Papadopoulos, A.; Humphrey, J.D.; Delp, M.D. Effects of aging on vasoconstrictor and mechanical properties of rat skeletal muscle arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002, 282, H1843–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.S.; Kim, S.; Dominguez, J.M.; Sindler, A.L.; Dick, G.M.; Muller-Delp, J.M. Aging and muscle fiber type alter K+ channel contributions to the myogenic response in skeletal muscle arterioles. J. Appl. Physiol 2009, 107, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Mora Solis, F.R.; Dominguez, J.M., 2nd; Spier, S.A.; Donato, A.J.; Delp, M.D.; Muller-Delp, J.M. Exercise training reverses aging-induced impairment of myogenic constriction in skeletal muscle arterioles. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2015, 118, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayoz, S.; Pettis, J.; Bradley, V.; Segal, S.S.; Jackson, W.F. Increased amplitude of inward rectifier K(+) currents with advanced age in smooth muscle cells of murine superior epigastric arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2017, 312, H1203–H1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, R.D.; Muller-Delp, J.M. Aging decreases vasoconstrictor responses of coronary resistance arterioles through endothelium-dependent mechanisms. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005, 66, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vessieres, E.; Dib, A.; Bourreau, J.; Lelievre, E.; Custaud, M.A.; Lelievre-Pegorier, M.; Loufrani, L.; Henrion, D.; Fassot, C. Long Lasting Microvascular Tone Alteration in Rat Offspring Exposed In Utero to Maternal Hyperglycaemia. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0146830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björling, K.; Joseph, P.D.; Egebjerg, K.; Salomonsson, M.; Hansen, J.L.; Ludvigsen, T.P.; Jensen, L.J. Role of age, Rho-kinase 2 expression, and G protein-mediated signaling in the myogenic response in mouse small mesenteric arteries. Physiol Rep 2018, 6, e13863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gros, R.; Van, W.R.; You, X.; Thorin, E.; Husain, M. Effects of age, gender, and blood pressure on myogenic responses of mesenteric arteries from C57BL/6 mice. Am. J. Physiol Heart Circ. Physiol 2002, 282, H380–H388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurley, A.; McGraw, A.; Pruthi, D.; Jaffe, I.Z. Smooth muscle cell mineralocorticoid receptors: role in vascular function and contribution to cardiovascular disease. Pflugers Arch. 2013, 465, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPont, J.J.; McCurley, A.; Davel, A.P.; McCarthy, J.; Bender, S.B.; Hong, K.; Yang, Y.; Yoo, J.K.; Aronovitz, M.; Baur, W.E.; et al. Vascular mineralocorticoid receptor regulates microRNA-155 to promote vasoconstriction and rising blood pressure with aging. JCI. Insight 2016, 1, e88942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgeon-Chartier, C.; Menguy, C.; Prevot, A.; Morel, J.L. Effect of aging on calcium signaling in C57Bl6J mouse cerebral arteries. Pflugers Arch. 2013, 465, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, F.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, F.; Shi, L. Epigenetic regulation of L-type voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels in mesenteric arteries of aging hypertensive rats. Hypertens. Res. 2017, 40, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korzick, D.H.; Muller-Delp, J.M.; Dougherty, P.; Heaps, C.L.; Bowles, D.K.; Krick, K.K. Exaggerated coronary vasoreactivity to endothelin-1 in aged rats: role of protein kinase C. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005, 66, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, M.F.; Bjorling, K.; Jensen, L.J. Age-dependent impact of CaV 3.2 T-type calcium channel deletion on myogenic tone and flow-mediated vasodilatation in small arteries. J. Physiol 2016, 594, 5881–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Corsso, C.; Ostrovskaya, O.; McAllister, C.E.; Murray, K.; Hatton, W.J.; Gurney, A.M.; Spencer, N.J.; Wilson, S.M. Effects of aging on Ca2+ signaling in murine mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2006, 127, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björling, K.; Morita, H.; Olsen, M.F.; Prodan, A.; Hansen, P.B.; Lory, P.; Holstein-Rathlou, N.H.; Jensen, L.J. Myogenic tone is impaired at low arterial pressure in mice deficient in the low-voltage-activated CaV 3.1 T-type Ca(2+) channel. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 2013, 207, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harraz, O.F.; Abd El-Rahman, R.R.; Bigdely-Shamloo, K.; Wilson, S.M.; Brett, S.E.; Romero, M.; Gonzales, A.L.; Earley, S.; Vigmond, E.J.; Nygren, A.; et al. Ca(V)3.2 channels and the induction of negative feedback in cerebral arteries. Circ. Res 2014, 115, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, G.; Kassmann, M.; Cui, Y.; Matthaeus, C.; Kunz, S.; Zhong, C.; Zhu, S.; Xie, Y.; Tsvetkov, D.; Daumke, O.; et al. Age attenuates the T-type CaV 3.2-RyR axis in vascular smooth muscle. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Guo, W.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wan, T.; Jiang, C.; Ye, Y.; Lin, H.; Fan, G. Senolytics prevent caveolar Ca(V) 3.2-RyR axis malfunction in old vascular smooth muscle. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e14002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D.G.; Morielli, A.D.; Nelson, M.T.; Brayden, J.E. Transient receptor potential channels regulate myogenic tone of resistance arteries. Circ. Res 2002, 90, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, R.; Jensen, L.J.; Jian, Z.; Shi, J.; Hai, L.; Lurie, A.I.; Henriksen, F.H.; Salomonsson, M.; Morita, H.; Kawarabayashi, Y.; et al. Synergistic activation of vascular TRPC6 channel by receptor and mechanical stimulation via phospholipase C/diacylglycerol and phospholipase A2/omega-hydroxylase/20-HETE pathways. Circ. Res 2009, 104, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, E.; Thakore, P.; Ali, S.; Sanchez Solano, A.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Labelle-Dumais, C.; Chaumeil, M.M.; Gould, D.B.; Earley, S. Impaired intracellular Ca(2+) signaling contributes to age-related cerebral small vessel disease in Col4a1 mutant mice. Sci Signal 2023, 16, eadi3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marijic, J.; Li, Q.; Song, M.; Nishimaru, K.; Stefani, E.; Toro, L. Decreased expression of voltage- and Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels in coronary smooth muscle during aging. Circ. Res 2001, 88, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabaglino, M.B.; Wakabayashi, M.; Pearson, J.T.; Jensen, L.J. Effect of age on the vascular proteome in middle cerebral arteries and mesenteric resistance arteries in mice. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2021, 200, 111594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawarazaki, W.; Fujita, T. Role of Rho in Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, A.; Atassi, F.; Gaaya, A.; Leprince, P.; Le, F.C.; Soubrier, F.; Lompre, A.M.; Nadaud, S. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway is activated during advanced arterial aging in humans. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawarazaki, W.; Mizuno, R.; Nishimoto, M.; Ayuzawa, N.; Hirohama, D.; Ueda, K.; Kawakami-Mori, F.; Oba, S.; Marumo, T.; Fujita, T. Salt causes aging-associated hypertension via vascular Wnt5a under Klotho deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130, 4152–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisy, C.; Pinto, F.M.; Le Guen, M.; Naline, E.; Grassin Delyle, S.; Sage, E.; Candenas, M.L.; Devillier, P. Airway response to acute mechanical stress in a human bronchial model of stretch. Crit. Care 2011, 15, R208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, D.H.; Black, M.A.; Pyke, K.E.; Padilla, J.; Atkinson, G.; Harris, R.A.; Parker, B.; Widlansky, M.E.; Tschakovsky, M.E.; Green, D.J. Assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans: a methodological and physiological guideline. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 300, H2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradel, A.K.J.; Salomonsson, M.; Sorensen, C.M.; Holstein-Rathlou, N.H.; Jensen, L.J. Long-term diet-induced hypertension in rats is associated with reduced expression and function of small artery SK(Ca), IK(Ca), and Kir2. 1 channels. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2018, 132, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thijssen, D.H.J.; Bruno, R.M.; van Mil, A.; Holder, S.M.; Faita, F.; Greyling, A.; Zock, P.L.; Taddei, S.; Deanfield, J.E.; Luscher, T.; et al. Expert consensus and evidence-based recommendations for the assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 2534–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, J.; Nilsson, P.M.; Kotsis, V.; Olsen, M.H.; Grassi, G.; Yumuk, V.; Hauner, H.; Zahorska-Markiewicz, B.; Toplak, H.; Engeli, S.; Finer, N. Joint scientific statement of the European Association for the Study of Obesity and the European Society of Hypertension: Obesity and early vascular ageing. J. Hypertens. 2015, 33, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, N.D.; Dengel, D.R.; Stratton, G.; Kelly, A.S.; Steinberger, J.; Zavala, H.; Marlatt, K.; Perry, D.; Naylor, L.H.; Green, D.J. Age and sex relationship with flow-mediated dilation in healthy children and adolescents. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2015, 119, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskurza, I.; Monahan, K.D.; Robinson, J.A.; Seals, D.R. Effect of acute and chronic ascorbic acid on flow-mediated dilatation with sedentary and physically active human ageing. J. Physiol. 2004, 556, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, F.; Ghiadoni, L.; Galetta, F.; Plantinga, Y.; Lubrano, V.; Huang, Y.; Salvetti, G.; Regoli, F.; Taddei, S.; Santoro, G.; Salvetti, A. Physical activity, plasma antioxidant capacity, and endothelium-dependent vasodilation in young and older men. Am. J. Hypertens. 2005, 18, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.A.; Ridout, S.J.; Proctor, D.N. Age and flow-mediated dilation: a comparison of dilatory responsiveness in the brachial and popliteal arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 291, H3043–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, A.J.; Eskurza, I.; Silver, A.E.; Levy, A.S.; Pierce, G.L.; Gates, P.E.; Seals, D.R. Direct evidence of endothelial oxidative stress with aging in humans: relation to impaired endothelium-dependent dilation and upregulation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane-Cordova, A.D.; Ranadive, S.M.; Kappus, R.M.; Cook, M.D.; Phillips, S.A.; Woods, J.A.; Wilund, K.R.; Baynard, T.; Fernhall, B. Aging, not age-associated inflammation, determines blood pressure and endothelial responses to acute inflammation. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 2402–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, M.J.; Groot, H.J.; Garten, R.S.; Witman, M.A.; Richardson, R.S. Vascular function assessed by passive leg movement and flow-mediated dilation: initial evidence of construct validity. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2016, 311, H1277–H1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Larson, M.G.; Keyes, M.J.; Mitchell, G.F.; Vasan, R.S.; Keaney, J.F., Jr.; Lehman, B.T.; Fan, S.; Osypiuk, E.; Vita, J.A. Clinical correlates and heritability of flow-mediated dilation in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2004, 109, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossman, M.J.; Santos-Parker, J.R.; Steward, C.A.C.; Bispham, N.Z.; Cuevas, L.M.; Rosenberg, H.L.; Woodward, K.A.; Chonchol, M.; Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Murphy, M.P.; Seals, D.R. Chronic Supplementation With a Mitochondrial Antioxidant (MitoQ) Improves Vascular Function in Healthy Older Adults. Hypertension 2018, 71, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, A.M.; Zinkevich, N.; Miller, B.; Liu, Y.; Wittenburg, A.L.; Mitchell, M.; Galdieri, R.; Sorokin, A.; Gutterman, D.D. Transition in the mechanism of flow-mediated dilation with aging and development of coronary artery disease. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2017, 112, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuler, D.; Sansone, R.; Freudenberger, T.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Weber, G.; Momma, T.Y.; Goy, C.; Altschmied, J.; Haendeler, J.; Fischer, J.W.; et al. Measurement of endothelium-dependent vasodilation in mice--brief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 2651–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delp, M.D.; Behnke, B.J.; Spier, S.A.; Wu, G.; Muller-Delp, J.M. Ageing diminishes endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and tetrahydrobiopterin content in rat skeletal muscle arterioles. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.M.; Park, S.K.; Kwon, O.S.; Taylor La Salle, D.; Cerbie, J.; Fermoyle, C.C.; Morgan, D.; Nelson, A.; Bledsoe, A.; Bharath, L.P.; et al. Activating P2Y1 receptors improves function in arteries with repressed autophagy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.S.; Reyes, R.A.; Muller-Delp, J.M. Aging impairs flow-induced dilation in coronary arterioles: role of NO and H(2)O(2). Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009, 297, H1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.S.; Chen, B.; Reyes, R.A.; Leblanc, A.J.; Teng, B.; Mustafa, S.J.; Muller-Delp, J.M. Aging and estrogen alter endothelial reactivity to reactive oxygen species in coronary arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 300, H2105–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, E.P.; Dukes, M.; Rowe, G.; Beare, J.E.; Nair, R.; LeBlanc, A.J. Stromal Vascular Fraction Restores Vasodilatory Function by Reducing Oxidative Stress in Aging-Induced Coronary Microvascular Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2023, 38, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, I.A.; Xu, Y.; Davidge, S.T. Age-associated impairment in vasorelaxation to fluid shear stress in the female vasculature is improved by TNF-alpha antagonism. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 290, H1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Bohlen, H.G.; Unthank, J.L.; Miller, S.J. Abnormal nitric oxide production in aged rat mesenteric arteries is mediated by NAD(P)H oxidase-derived peroxide. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009, 297, H2227–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, J.S.; Rueda-Clausen, C.F.; Davidge, S.T. Flow-mediated vasodilation is impaired in adult rat offspring exposed to prenatal hypoxia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011, 110, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinaud, F.; Bocquet, A.; Dumont, O.; Retailleau, K.; Baufreton, C.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Loufrani, L.; Henrion, D. Paradoxical role of angiotensin II type 2 receptors in resistance arteries of old rats. Hypertension 2007, 50, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Huang, A.; Yan, E.H.; Wu, Z.; Yan, C.; Kaminski, P.M.; Oury, T.D.; Wolin, M.S.; Kaley, G. Reduced release of nitric oxide to shear stress in mesenteric arteries of aged rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286, H2249–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvany, M.J. Vascular remodelling of resistance vessels: can we define this? Cardiovasc. Res 1999, 41, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludvigsen, T.P.; Olsen, L.H.; Pedersen, H.D.; Christoffersen, B.O.; Jensen, L.J. Hyperglycemia-induced transcriptional regulation of ROCK1 and TGM2 expression is involved in small artery remodeling in obese diabetic Gottingen Minipigs. Clin. Sci. (Lond) 2019, 133, 2499–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buus, N.H.; Mathiassen, O.N.; Fenger-Gron, M.; Praestholm, M.N.; Sihm, I.; Thybo, N.K.; Schroeder, A.P.; Thygesen, K.; Aalkjaer, C.; Pedersen, O.L.; et al. Small artery structure during antihypertensive therapy is an independent predictor of cardiovascular events in essential hypertension. J. Hypertens 2013, 31, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Rizzoni, D. Microvascular structure as a prognostically relevant endpoint. J. Hypertens 2017, 35, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatta, E.G. The reality of aging viewed from the arterial wall. Artery Res 2013, 7, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P.M. Hemodynamic Aging as the Consequence of Structural Changes Associated with Early Vascular Aging (EVA). Aging Dis. 2014, 5, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.; Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. Vascular biology of ageing-Implications in hypertension. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 83, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, K. Tunica intima compensation for reduced stiffness of the tunica media in aging renal arteries as measured with scanning acoustic microscopy. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0234759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Froehlich, J.; Galis, Z.S.; Lakatta, E.G. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in the thickened intima of aged rats. Hypertension 1999, 33, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Takagi, G.; Asai, K.; Resuello, R.G.; Natividad, F.F.; Vatner, D.E.; Vatner, S.F.; Lakatta, E.G. Aging increases aortic MMP-2 activity and angiotensin II in nonhuman primates. Hypertension 2003, 41, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, L.Q.; Spinetti, G.; Pintus, G.; Monticone, R.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Virmani, R.; Lakatta, E.G. Proinflammatory profile within the grossly normal aged human aortic wall. Hypertension 2007, 50, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, D.; Spinetti, G.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, L.Q.; Pintus, G.; Monticone, R.; Lakatta, E.G. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 activation of transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) and TGF-beta1-type II receptor signaling within the aged arterial wall. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longtine, A.G.; Venkatasubramanian, R.; Zigler, M.C.; Lindquist, A.J.; Mahoney, S.A.; Greenberg, N.T.; VanDongen, N.S.; Ludwig, K.R.; Moreau, K.L.; Seals, D.R.; Clayton, Z.S. Female C57BL/6N mice are a viable model of aortic aging in women. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2023, 324, H893–H904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasmin; McEniery, C.M.; Wallace, S.; Dakham, Z.; Pulsalkar, P.; Maki-Petaja, K.; Ashby, M.J.; Cockcroft, J.R.; Wilkinson, I.B. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), MMP-2, and serum elastase activity are associated with systolic hypertension and arterial stiffness. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieman, S.J.; Melenovsky, V.; Clattenburg, L.; Corretti, M.C.; Capriotti, A.; Gerstenblith, G.; Kass, D.A. Advanced glycation endproduct crosslink breaker (alagebrium) improves endothelial function in patients with isolated systolic hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2007, 25, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabot, N.; Moreau, S.; Mulani, A.; Moreau, P.; Keillor, J.W. Fluorescent probes of tissue transglutaminase reveal its association with arterial stiffening. Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.M.; Duranti, E.; Ippolito, C.; Segnani, C.; Bernardini, N.; Di, C.G.; Chiarugi, M.; Taddei, S.; Virdis, A. Different Impact of Essential Hypertension on Structural and Functional Age-Related Vascular Changes. Hypertension 2017, 69, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, M.A.; Taylor, C.R.; Chen, B.; La, H.S.; Maraj, J.J.; Kilar, C.R.; Behnke, B.J.; Delp, M.D.; Muller-Delp, J.M. Structural remodeling of coronary resistance arteries: effects of age and exercise training. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014, 117, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnke, B.J.; Prisby, R.D.; Lesniewski, L.A.; Donato, A.J.; Olin, H.M.; Delp, M.D. Influence of ageing and physical activity on vascular morphology in rat skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2006, 575, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, P.; d’Uscio, L.V.; Luscher, T.F. Structure and reactivity of small arteries in aging. Cardiovasc. Res. 1998, 37, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumer, N.; Toklu, H.Z.; Muller-Delp, J.M.; Oktay, S.; Ghosh, P.; Strang, K.; Delp, M.D.; Scarpace, P.J. The effects of aging on the functional and structural properties of the rat basilar artery. Physiol Rep 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandala, M.; Pedatella, A.L.; Morales Palomares, S.; Cipolla, M.J.; Osol, G. Maturation is associated with changes in rat cerebral artery structure, biomechanical properties and tone. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 2012, 205, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzechorzek, W.; Zhang, H.; Buckley, B.K.; Hua, K.; Pomp, D.; Faber, J.E. Aerobic exercise prevents rarefaction of pial collaterals and increased stroke severity that occur with aging. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 3544–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Otero, J.M.; Garver, H.; Fink, G.D.; Jackson, W.F.; Dorrance, A.M. Aging is associated with changes to the biomechanical properties of the posterior cerebral artery and parenchymal arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2016, 310, H365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan, J.L.; Blaser, M.C.; Pang, J.J.; Adams, S.M.; Pang, S.C.; Adams, M.A. Impact of hypertension, aging, and antihypertensive treatment on the morphology of the pudendal artery. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, C.J.; Sweeney, M.; Robson, S.C.; Taggart, M.J. Estrogenic vascular effects are diminished by chronological aging. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, J.; Liao, A.; Forman, S.P.; Ohanian, V. Age-related remodeling of small arteries is accompanied by increased sphingomyelinase activity and accumulation of long-chain ceramides. Physiol Rep 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freidja, M.L.; Vessieres, E.; Clere, N.; Desquiret, V.; Guihot, A.L.; Toutain, B.; Loufrani, L.; Jardel, A.; Procaccio, V.; Faure, S.; Henrion, D. Heme oxygenase-1 induction restores high-blood-flow-dependent remodeling and endothelial function in mesenteric arteries of old rats. J. Hypertens. 2011, 29, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones, A.M.; Salaices, M.; Vila, E. Mechanisms underlying hypertrophic remodeling and increased stiffness of mesenteric resistance arteries from aged rats. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, O.; Pinaud, F.; Guihot, A.L.; Baufreton, C.; Loufrani, L.; Henrion, D. Alteration in flow (shear stress)-induced remodelling in rat resistance arteries with aging: improvement by a treatment with hydralazine. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 77, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausman, N.; Martin, J.; Taggart, M.J.; Austin, C. Age-related changes in the contractile and passive arterial properties of murine mesenteric small arteries are altered by caveolin-1 knockout. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012, 16, 1720–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillon, A.; Grenier, C.; Grimaud, L.; Vessieres, E.; Guihot, A.L.; Blanchard, S.; Lelievre, E.; Chabbert, M.; Foucher, E.D.; Jeannin, P.; et al. The angiotensin II type 2 receptor activates flow-mediated outward remodelling through T cells-dependent interleukin-17 production. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016, 112, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Altayo, F.; Sanchez-Ventura, J.; Vila, E.; Gimenez-Llort, L. Crosstalk between Peripheral Small Vessel Properties and Anxious-like Profiles: Sex, Genotype, and Interaction Effects in Mice with Normal Aging and 3xTg-AD mice at Advanced Stages of Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 62, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhouni, K.; Freidja, M.L.; Guihot, A.L.; Vessieres, E.; Grimaud, L.; Toutain, B.; Lenfant, F.; Arnal, J.F.; Loufrani, L.; Henrion, D. Role of estrogens and age in flow-mediated outward remodeling of rat mesenteric resistance arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2014, 307, H504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, L.; Monticone, R.E.; Lakatta, E.G. Proinflammation: the key to arterial aging. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.; Montezano, A.C.; Lopes, R.A.; Rios, F.; Touyz, R.M. Vascular Fibrosis in Aging and Hypertension: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehaitly, A.; Vessieres, E.; Guihot, A.L.; Henrion, D. Flow-mediated outward arterial remodeling in aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2021, 194, 111416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, C.K.; Yi, M.; Lui, K.O.; Huang, Y. Targeting endothelial dysfunction and inflammation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2022, 168, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemkens, P.; Boari, G.; Fazzi, G.; Janssen, G.; Murphy-Ullrich, J.; Schiffers, P.; De Mey, J. Thrombospondin-1 in early flow-related remodeling of mesenteric arteries from young normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2012, 6, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashiro, Y.; Thang, B.Q.; Ramirez, K.; Shin, S.J.; Kohata, T.; Ohata, S.; Nguyen, T.A.V.; Ohtsuki, S.; Nagayama, K.; Yanagisawa, H. Matrix mechanotransduction mediated by thrombospondin-1/integrin/YAP in the vascular remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 9896–9905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevitt, C.; McKenzie, G.; Christian, K.; Austin, J.; Hencke, S.; Hoying, J.; LeBlanc, A. Physiological levels of thrombospondin-1 decrease NO-dependent vasodilation in coronary microvessels from aged rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2016, 310, H1842–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isenberg, J.S.; Hyodo, F.; Pappan, L.K.; Abu-Asab, M.; Tsokos, M.; Krishna, M.C.; Frazier, W.A.; Roberts, D.D. Blocking thrombospondin-1/CD47 signaling alleviates deleterious effects of aging on tissue responses to ischemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 2582–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santinha, D.; Vilaca, A.; Estronca, L.; Schuler, S.C.; Bartoli, C.; De Sandre-Giovannoli, A.; Figueiredo, A.; Quaas, M.; Pompe, T.; Ori, A.; Ferreira, L. Remodeling of the Cardiac Extracellular Matrix Proteome During Chronological and Pathological Aging. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2024, 23, 100706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, J.C.; Mulvany, M.J.; Holstein-Rathlou, N.H. A mechanism for arteriolar remodeling based on maintenance of smooth muscle cell activation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2008, 294, R1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Joseph, P.D.; Christensen, V.G.; Jensen, L.J.; Jacobsen, J.C.B. Lack of tone in mouse small mesenteric arteries leads to outward remodeling, which can be prevented by prolonged agonist-induced vasoconstriction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H644–H657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Uniprot ID (Homo sapiens) | Gene name | Protein (short name) | Protein name |

|---|---|---|---|

| P60709 | ACTB | Beta-actin | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 |

| P30542 | ADORA1 | A1-R | Adenosine receptor A1 |

| P30556 | AGTR1 | AT1-R | Type-1 angiotensin II receptor |

| P50052 | AGTR2 | AT2-R | Type-2 angiotensin II receptor |

| Q06278 | AOX1 | AOXA | Aldehyde oxidase |

| Q14155 | ARHGEF7 | RhoGEF7/β-Pix | Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 7 |

| P16615 | ATP2A2 | SERCA2 | Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 |

| O73707 | Cacna1C | CaV1.2 | Voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel subunit alpha-1C |

| O43497 | Cacna1g | CaV3.1 | Voltage-dependent T-type calcium channel subunit alpha-3G |

| O95180 | Cacna1h | CaV3.2 | Voltage-dependent T-type calcium channel subunit alpha-3H |

| P02462 | COL4A1 | Col4a1 | Collagen alpha-1(IV) chain |

| P10606 | COX5B | COX5B | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5B, mitochondrial |

| P25101 | EDNRA | ETA-R | Endothelin receptor type A |

| P24530 | EDNRB | ETB-R | Endothelin receptor type B |

| P03372 | ESR1 | ER | Estrogen receptor |

| O95967 | FBLN4 | Fibulin-4 | EGF-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 2 |

| Q14643 | ITPR1 | InsP3R1 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 |

| P63252 | KCNJ2 | Kir2.1 | Inward rectifier potassium channel 2 |

| Q12791 | KCNMA1 | BKCa α-subunit | Calcium-activated potassium channel subunit alpha-1 |

| Q16787 | LAMA3 | Laminin α3 | Laminin subunit alpha-3 |

| P55001 | MFAP2 | MFAP-2 | Microfibrillar-associated protein 2 |

| Q08431 | MFGE8 | MFG-E8 | Lactadherin |

| P08253 | MMP2 | MMP-2 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

| P14780 | MMP9 | MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| Q6WCQ1 | MPRIP | M-RIP/p116RIP | Myosin phosphatase Rho-interacting protein |

| O14950 | MYL12B | MLC20 | Myosin regulatory light chain 12B |

| Q9ULV0 | MYO5B | MYO5B | Unconventional myosin-Vb |

| P19838 | NFKB1 | NF-κB | Nuclear factor NF-kappa-B p105 subunit |

| P29474 | NOS3 | NOS3/eNOS | Nitric oxide synthase 3 |

| Q9NPH5 | NOX4 | NOX4 | NADPH oxidase 4 |

| P08235 | NR3C2 | MR | Mineralocorticoid receptor |

| P47900 | P2RY1 | P2Y1-R | P2Y purinoceptor 1 |

| Q13177 | PAK2 | PAK-2/p58 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase PAK 2 |

| P26678 | PLN | PLB | Cardiac phospholamban |

| P43088 | PTGFR | PGF2α-R | Prostaglandin F2-alpha receptor |

| Q13464 | ROCK1 | ROCK1 | Rho-associated protein kinase 1 |

| O75116 | ROCK2 | ROCK2 | Rho-associated protein kinase 2 |

| Q92736 | RYR2 | RYR2 | Ryanodine receptor 2 |

| P00441 | SOD1 | Sod1 | Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] |

| Q13586 | STIM1 | STIM1 | Stromal interaction molecule 1 |

| P21731 | TBXA2R | TXA2-R | Thromboxane A2 receptor |

| A0A499FJK2 | TGFB1 | TGFβ1 | Transforming growth factor beta |

| P37173 | TGFBR2 | TGFR-2 | TGF-beta receptor type-2 |

| P21980 | TGM2 | TGM2 | Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 (Transglutaminase 2) |

| P07996 | THBS1 | TSP-1 | Thrombospondin-1 |

| P01375 | TNF | TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor |

| Q9Y210 | TRPC6 | TrpC6 | Short transient receptor potential channel 6 |

| Q8TD43 | TRPM4 | TrpM4 | Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 4 |

| Q9H4B7 | TUBB1 | Tubulin β1 | Tubulin beta-1 chain |

| Q9GZT5 | WNT10A | Wnt-10a | Protein Wnt-10a |

| P56704 | WNT3A | Wnt-3a | Protein Wnt-3a |

| P41221 | WNT5A | Wnt-5a | Protein Wnt-5a |

| Q9NUD5 | ZCCHC3 | ZCHC3 | Zinc finger CCHC domain-containing protein 3 |

| Pathway term | % occurrence* | P-value | FDR** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium signaling pathway | 26 | 2,80E-09 | 2,80E-07 |

| Proteoglycans in cancer | 24 | 3,90E-09 | 2,80E-07 |

| cGMP-PKG signaling pathway | 20 | 1,20E-07 | 5,60E-06 |

| AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications | 16 | 6,10E-07 | 1,80E-05 |

| Diabetic cardiomyopathy | 20 | 6,30E-07 | 1,80E-05 |

| Pathways in cancer | 28 | 1,40E-06 | 3,20E-05 |

| Platelet activation | 16 | 2,60E-06 | 5,20E-05 |

| Renin secretion | 12 | 2,40E-05 | 4,20E-04 |

| Relaxin signaling pathway | 14 | 4,40E-05 | 6,80E-04 |

| Pathways of neurodegeneration—multiple diseases | 22 | 1,10E-04 | 1,50E-03 |

| Cushing syndrome | 14 | 1,20E-04 | 1,50E-03 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 12 | 1,60E-04 | 1,90E-03 |

| Focal adhesion | 14 | 5,20E-04 | 5,60E-03 |

| Alzheimer disease | 18 | 6,10E-04 | 6,10E-03 |

| Oxytocin signaling pathway | 12 | 1,00E-03 | 9,70E-03 |

| Pathway term | % occurrence* | P-value | FDR** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle contraction | 5 | 1.40e-07 | 5.81e-05 |

| EPH-Ephrin signaling | 8 | 6.89e-07 | 1.43e-04 |

| Extra-nuclear estrogen signaling | 8 | 4.91e-06 | 6.77e-04 |

| Signal Transduction | 1 | 7.76e-06 | 8.07e-04 |

| Ion homeostasis | 9 | 1.17e-05 | 9.67e-04 |

| Signaling by GPCR | 2 | 2.06e-05 | 0.001 |

| GPCR ligand binding | 2 | 3.82e-05 | 0.002 |

| Signal amplification | 11 | 4.11e-05 | 0.002 |

| Cardiac conduction | 5 | 7.34e-05 | 0.003 |

| Smooth Muscle Contraction | 9 | 9.89e-05 | 0.004 |

| Nuclear Receptor transcription pathway | 6 | 1.05e-04 | 0.004 |

| Hemostasis | 2 | 1.11e-04 | 0.004 |

| Platelet homeostasis | 6 | 1.16e-04 | 0.004 |

| Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases | 2 | 1.57e-04 | 0.005 |

| Axon guidance | 2 | 1.75e-04 | 0.005 |

| Gene name (Homo sapiens) | Protein name | Score |

|---|---|---|

| BCL3 | B-cell lymphoma 3 protein | 0.999 |

| COX6A1 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 6A1, mitochondrial | 0.999 |

| DCN | Decorin | 0.999 |

| NFKBIA | NF-kappa-B inhibitor alpha | 0.999 |

| PFN1 | Profilin-1 | 0.999 |

| RELB | Transcription factor RelB | 0.999 |

| TGFB3 | Transforming growth factor beta-3 proprotein | 0.999 |

| TIMP1 | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 | 0.999 |

| TNFRSF1A | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A, membrane form | 0.999 |

| UQCRC1 | Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1, mitochondrial | 0.999 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).