1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer, often characterized by late diagnosis and an aggressive nature, has one of the poorest prognoses among gynecological diseases [

1]. Due to the absence of apparent symptoms during the early stages, its clinical manifestations typically appear only after metastasis to other organs, resulting in late-stage detection. Ovarian cancer originating from ovarian surface epithelial cells accounts for more than 90% of all ovarian cancer cases [

2]. The standard treatment for ovarian cancer involves surgery followed by paclitaxel (PTX) and carboplatin chemotherapy [

3]. However, the development of drug resistance in ovarian cancer cells poses a significant challenge in achieving long-term treatment success with these conventional therapies.

Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1/redox factor 1 (APE1/Ref-1) is a multifunctional secreted protein that has recently emerged as a potential biomarker of various disorders [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The extracellular roles of secreted APE1/Ref-1 are being increasingly recognized. Studies have revealed that extracellular APE1/Ref-1 can mitigate systemic inflammation through a thiol-exchange mechanism in endothelial cells

in vivo [

8,

9]. Earlier research has suggested that acetylated secretory APE1/Ref-1 induces apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer, indicating the therapeutic potential of acetylated APE1/Ref-1 in cancer [

10]. Following acetylation, secreted APE1/Ref-1 binds to a receptor for advanced glycation end products, initiating apoptotic cell death in triple-negative breast cancer both

in vitro and

in vivo [

11,

12].

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to alleviate pain, manage arthritis, and prevent cardiovascular disease [

13]. Aspirin primarily exerts its effects by acetylating and inhibiting cyclooxygenase activity [

14]. Several studies have reported the efficacy of aspirin for the treatment of ovarian cancer [

15,

16]. The prolonged use of low-dose aspirin has been associated with a reduced risk of ovarian, endometrial, and cervical cancers [

17]. Furthermore, aspirin has demonstrated potential as an adjuvant for enhancing the sensitivity of cancer cells to conventional chemotherapeutic drugs.

In vitro experiments have shown that aspirin increases the sensitivity of epithelial ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin by inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis [

18].

PTX is a chemotherapeutic drug commonly used to treat various cancers, including ovarian cancer [

19]. PTX interferes with the normal function of microtubules, which are essential for cell division [

20]. PTX is often used in combination with other chemotherapeutic drugs, and combination therapies are frequently employed for both first-line treatment and the treatment of recurrent or advanced stages of ovarian cancer. However, PTX-resistant cells have been reported in various studies, highlighting a significant challenge for the effective treatment of certain cancers [

21].

Despite advances in cancer research and treatment, ovarian cancer remains a challenging and often deadly disease. New and innovative treatment strategies are needed to improve patient outcomes, reduce toxicity, and enhance the efficacy of existing therapies. In this study, we investigated whether combination therapy involving recombinant human APE1/Ref-1 and aspirin leads to cell death in ovarian cancer cell lines, particularly those resistant to PTX, such as PEO14 cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The human ovarian cancer cell line PEO14 was purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Salisbury, UK). The human ovarian cancer cell line CAOV-3 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; C2517A) and endothelial growth medium (EGM-2) were obtained from Lonza Biosciences (Walkersville, MD, USA). RPMI 1640 medium, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), and Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) were obtained from Welgen (Gyeongsan, Gyeongsangbukdo, Republic of Korea). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotics, and trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). ASA, PTX, thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The Caspase-Glo® 3/7 assay kit was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Recombinant human APE1/Ref-1 protein (rhAPE1/Ref-1; < 1 endotoxin unit per microgram) was purchased from MediRedox (Daejeon, Korea). Antibodies against acetyl-lysine were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA), anti-β-actin from Sigma-Aldrich, and A/G agarose beads from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) antibodies were provided by Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). Monoclonal anti-APE1/Ref-1 (clone 14E1) and polyclonal anti-APE1/Ref-1 antibodies were purchased from MediRedox (Daejeon, South Korea).

2.2. Cell Culture

PEO14 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 1% antibiotics. CAOV-3 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics. HUVECs were cultured using an endothelial growth medium (EGM-2) kit. All cell lines were incubated under humid conditions at 37°C and 5% CO2.

2.3. Cell Viability Analysis Using the MTT Assay

Cell viability was determined using the MTT assay [

22]. Two ovarian cancer cell lines, PEO14 and CAOV-3, along with HUVECs, 10

4 cells were plated in a 96-well clear microplate with a flat bottom and treated with rhAPE1/Ref-1 or ASA for 24 h. After incubation, 10 µl of MTT reagent (5 mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Subsequently, 100 µl of DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals, incubating in the dark for 15 min. Finally, the absorbance of each well at a wavelength of 600 nm was measured using a microplate reader (GloMax Discover, Promega).

2.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis for Apoptosis

Flow cytometry using the Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/propidium iodide (PI) staining method was used to monitor apoptosis [

23]. Briefly, the cells were washed, trypsinized, and resuspended in the staining solution provided with the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) following the manufacturer’s protocol. After incubation for 10 min, apoptosis was assessed using a flow cytometer (FACSCanto; BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Viable cells were identified as Annexin V-negative and PI-negative and counted in the lower left quadrant (Q4). Cells in early apoptosis were characterized as Annexin V-positive but PI-negative and were counted in the lower right quadrant (Q3). Late apoptosis is represented by Annexin V-positive and PI-positive cells and were counted in the upper right quadrant (Q2). Necrotic cells were defined as Annexin V-negative and PI-positive and were positioned in the upper left quadrant (Q1).

2.5. Immunofluorescence Staining

After seeding 1×105 ovarian cancer cells directly on coverslips, apoptosis was induced using ASA and rhAPE1/Ref-1. After incubation for 24 h, the cells were washed before being stained with a mixture of 5 μl Annexin V-FITC and 1 µg/ml PI. After a 5-min incubation in the dark, the cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde and washed thrice with the binding buffer. DAPI staining was then performed to label the cell nuclei. The coverslips were then mounted onto slides, and fluorescence microscopy was used to capture images.

2.6. Caspase-3/7 Activity Assay

A Caspase-Glo® 3/7 assay kit (Promega) was used to detect caspase activity. This reagent comprises a pro-luminescent caspase-3/7 substrate, which includes the tetrapeptide sequence DEVD, combined with luciferase and a cell-lysing agent. When the Caspase-Glo® 3/7 reagent was added directly to the assay well, cell lysis was induced, followed by the caspase-mediated cleavage of the DEVD substrate, resulting in luminescence. Caspase-3/7 activity was analyzed using a GloMax Luminometer (Promega).

2.7. In Vitro Acetylation Assay

An in vitro acetylation assay was conducted to confirm whether the acetylation of rhAPE1/Ref-1 was induced upon reaction with ASA in the culture medium. The resulting mixture was subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-APE1/Ref-1 antibody. Briefly, 1 µg of anti-APE1/Ref-1 antibody was added to the culture supernatant and incubated for 2 hours at 4°C. Protein A/G agarose beads were then added to each sample and incubated for 16 h at 4 . The immunoprecipitated complexes underwent two washes with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, 10 mM nicotinamide, 10 mM sodium butyrate, and 5 μM trichostatin A. Subsequently, the immune complexes were mixed with sample buffer and subjected to 10% Sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), followed by immunoblotting using anti-acetyl-lysine antibodies.

2.8. Western Blotting

Cells were washed with DPBS and harvested in 100 µl of lysis buffer. The cells were then lysed with a RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors, and the resulting lysates were cleared via centrifugation at 12,000 ×g for 20 min. Then, 30 µg of the total proteins were separated using a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. After blocking with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS containing 0.05% Tween-20, the membrane was incubated with antibodies against PARP (Plymouth Meeting) and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 18 h at 4°C. Subsequently, the membrane was treated with the corresponding peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, and the chemiluminescent signal was developed using SuperSignal West Pico or Femto Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). To normalize loading, each membrane was re-probed with an anti-β-actin antibody.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 8 (La Jolla, CA, USA). The statistical significance of the differences was determined using a paired t-test or one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s or Bonferroni multiple comparison tests. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

4. Discussion

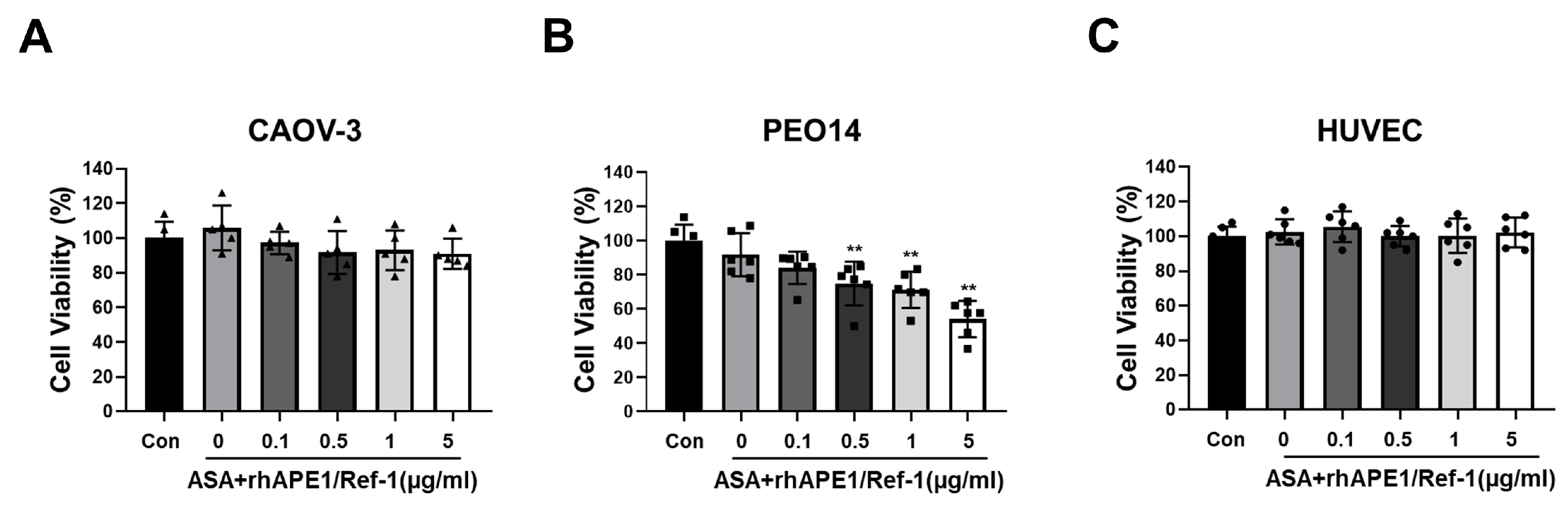

This study demonstrated the potential synergistic effects of combining rhAPE1/Ref-1 with ASA in ovarian cancer cells. The decreased cell viability and increased apoptotic effects in PEO14 cells suggest that this combination could be a promising therapeutic approach in ovarian cancer. Notably, the selectivity of this treatment without affecting normal endothelial cells is a significant advantage, emphasizing its potential clinical relevance.

In the present study, HUVECs were chosen as the control group because of their ability to mimic the vascular endothelial environment. As ovarian cancer treatments are commonly administered intravenously, HUVECs served as an appropriate control group to assess the potential impact of treatments on vascular endothelial cells. PEO14 is an adherent, well-differentiated ovarian cancer cell line derived from the malignant effusion in the peritoneal ascites of a patient diagnosed with well-differentiated serous adenocarcinoma. Notably, PEO14 is characterized by a lack of estrogen receptor expression, a feature established in the literature [

25]. The lack of estrogen receptors in PEO14 cells poses challenges for targeted treatment by drugs such as tamoxifen, potentially limiting the success of estrogen receptor-targeted therapies.

The present study focused on how the combination of the acetylated rhAPE1/Ref-1 and ASA, rather than ASA alone, enhances the cytotoxic antitumor effect. This choice was driven by concerns about the non-selective cytotoxicity associated with high doses of ASA. Moreover, this study aimed to investigate the effects of acetylated rhAPE1/Ref-1 on cancer cells that were already hyperacetylated by ASA. As an NSAID, ASA primarily inhibits cyclooxygenases. This inhibition reduces the production of proinflammatory prostaglandins (PGs) [

26]. In cancer cells, high PG levels promote cell survival and proliferation. Hence, by inhibiting COX, ASA may reduce the survival signals [

27]. Accumulating evidence suggests that the abnormal acetylation of DNA repair proteins contributes to the impairment of DNA repair mechanisms, the development and progression of cancer, and the sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapy. These insights into the role of acetylation and its implications in cancer have been reported previously [

20,

28]. In the present study, we treated PEO14 cells with 3 mM aspirin for 24 h to induce hyperacetylation, which did not result in cytotoxic effects. Therefore, it can be concluded that both the concentration (3 mM) and exposure duration (24 h) employed in this study are suitable for inducing hyperacetylation without affecting the viability of PEO14 ovarian cancer cells.

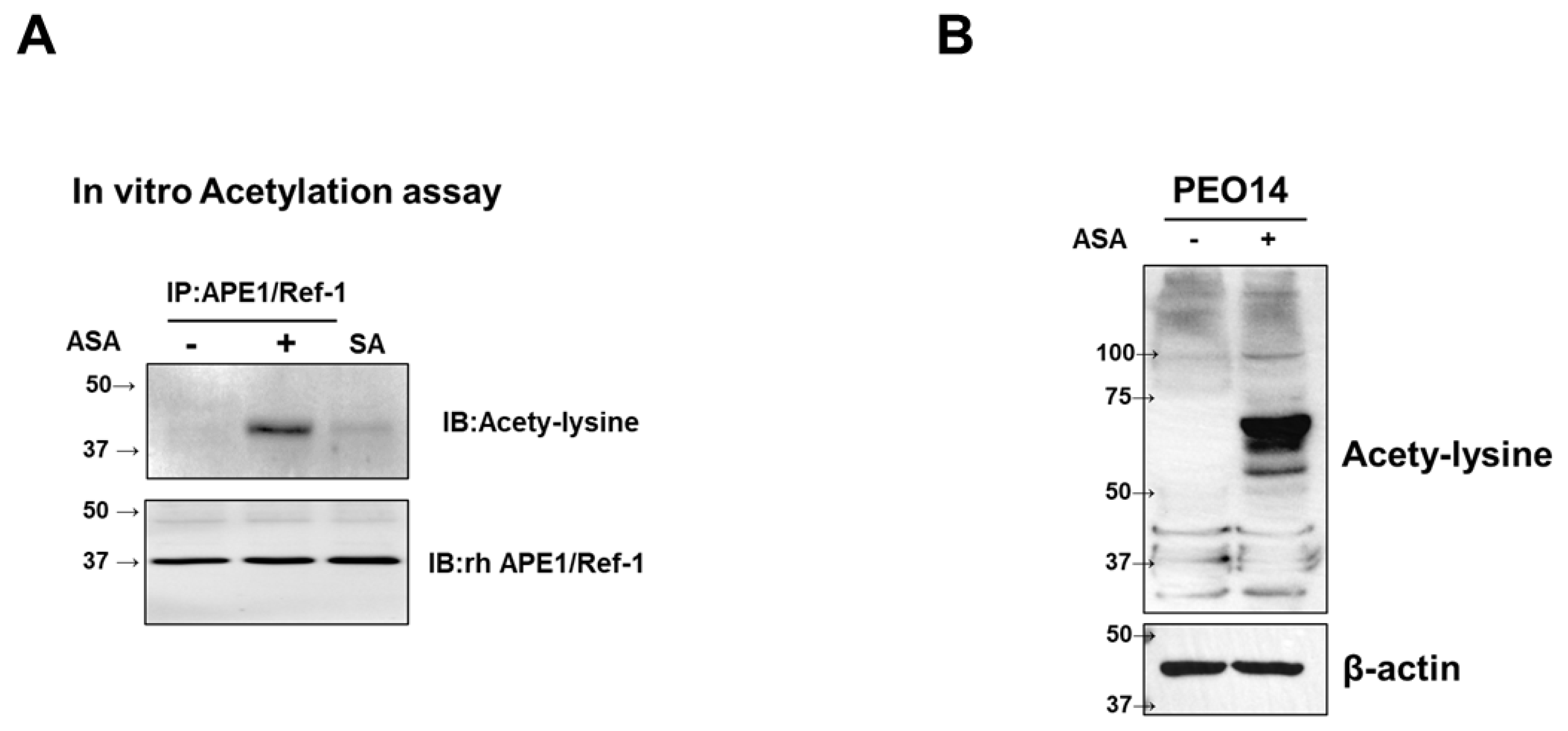

Acetylation is a post-translational modification in which an acetyl group is added to a protein. ASA successfully acetylated rhAPE1/Ref-1

in vitro in the culture medium (

Figure 2), revealing that ASA induced the acetylation of rhAPE1/Ref-1 under specific culture conditions. Therefore, we hypothesized that the reaction between rhAPE1/Ref-1 and ASA resulted in the formation of acetylated APE1/Ref-1. The primary reason for combining rhAPE1/Ref-1 with ASA was to prevent the deacetylation of acetylated rhAPE1/Ref-1, creating a promising combination therapeutic model for clinical use.

In this study, we demonstrated the potential selectivity of combining rhAPE1/Ref-1 with ASA to treat PEO14 cells. PEO14 is an estrogen receptor (ER)α-negative ovarian cancer cell line [

29]; in contrast, CaOV-3 cells are ER-positive [

30]. A previous study revealed that PEO14 cells displayed the highest level of resistance to PTX, whereas CAOV-3 cells exhibited heightened sensitivity [

31]. The selectivity of acetylated rhAPE1/Ref-1 was observed in PEO14 cells, while no effect was observed in CAOV-3 cells. This was likely influenced by variations in the genetic and molecular profiles of these cells. To further understand the underlying mechanisms, researchers should conduct detailed molecular analyses, such as gene expression profiling and proteomics or pathway analyses, to identify specific factors contributing to the observed selectivity in the hyperacetylation status of PEO14 and CAOV-3 cells.

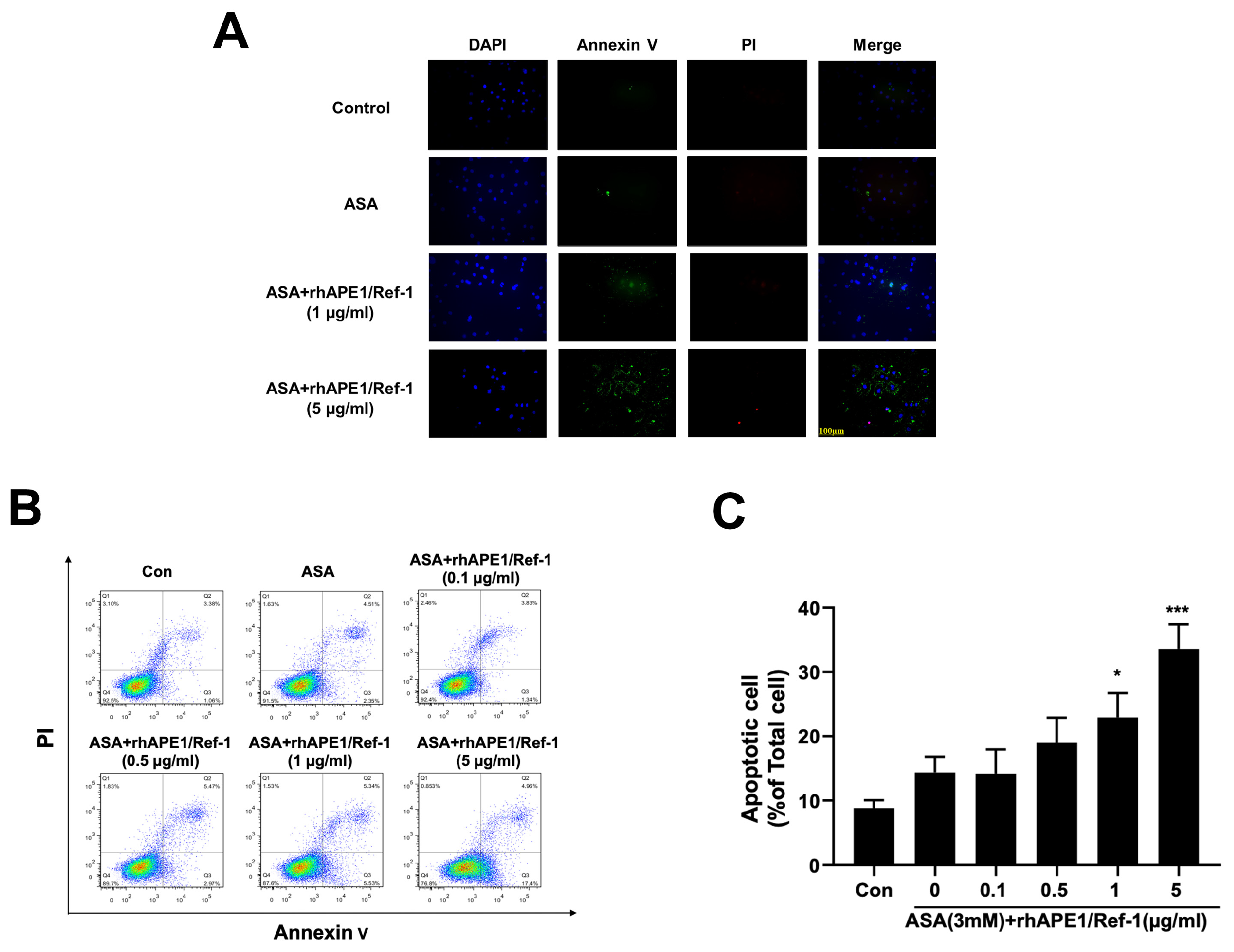

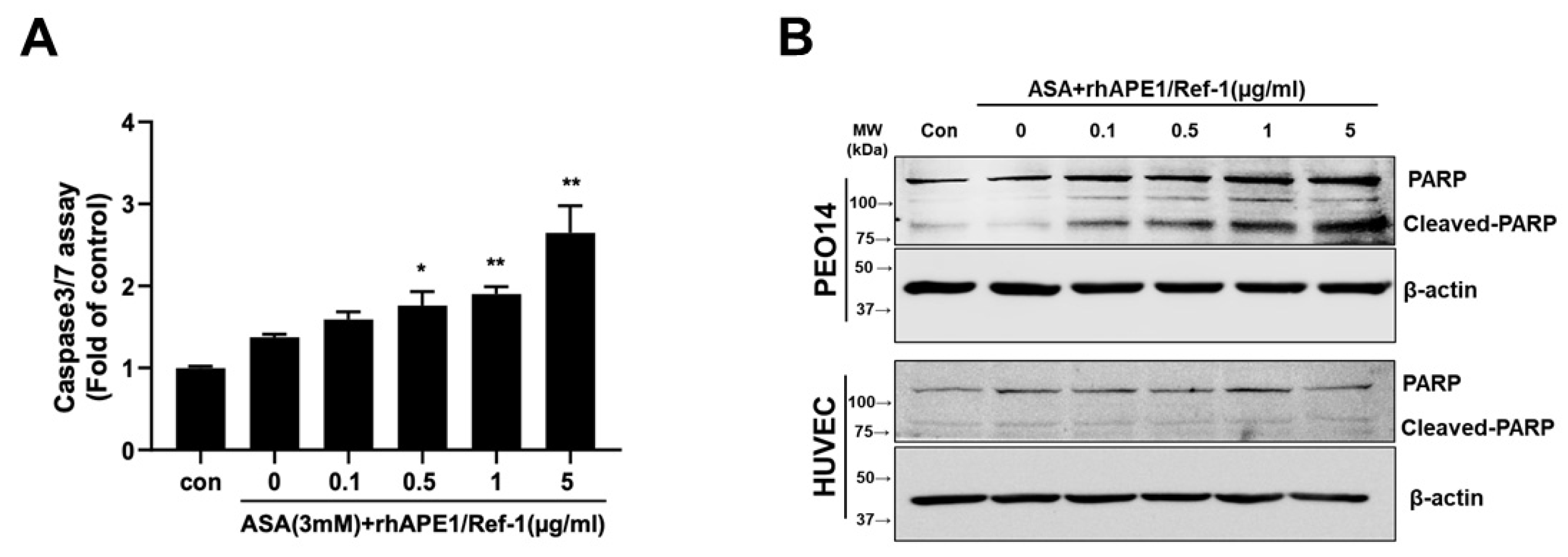

While treatment with ASA alone did not have an effect, combined treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 and ASA induced apoptotic cell death. This effect was evidenced by caspase-3/7 activation and PARP cleavage, suggesting that acetylated APE1/Ref-1 plays a role in reducing the viability of PEO14 cells. Caspases are a family of proteases that play a central role in programmed cell death [

32]. The activation of caspase-3/7 is particularly noteworthy because these enzymes are key players in apoptosis. Caspase activation initiates apoptosis, ultimately leading to cell death, thus presenting a potentially novel therapeutic approach for the management of ovarian cancer. Additionally, the combination of APE1/Ref-1 with ASA did not significantly increase PARP cleavage in HUVECs, suggesting its therapeutic potential for selectively regulating apoptosis pathways in PEO14 ovarian cancer cells without adversely affecting normal endothelial cells.

Although the induction of apoptosis by acetylated APE1/Ref-1 has been previously observed, the detailed mechanisms underlying this process remain unclear. However, stimulation of apoptosis by the binding of secreted acetylated APE1/Ref-1 to the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) has been identified as crucial for triple-negative breast cancer cell death in response to hyperacetylation. Notably, the stimulation of apoptosis by acetylated APE1/Ref-1 is significantly reduced in RAGE-knockdown tumors compared to RAGE-overexpressing tumors, even during hyperacetylation (12). Moreover, the role of extracellular APE1/Ref-1 in triggering apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells through RAGE binding mediated by acetylation has been demonstrated in studies involving co-treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors [

10]. The combination of aspirin-induced hyperacetylation with the binding of acetylated rhAPE1/Ref-1 to RAGE, which has a synergistic effect on apoptosis induction, has been proposed as an underlying mechanism [

10,

12]. Accumulating evidence has indicated that the aberrant acetylation of DNA repair proteins contributes to the dysfunction of DNA repair ability, pathogenesis and progression of cancer, and chemosensitivity of cancer cells [

20]. Therefore, APE1/Ref-1 and its hyperacetylation may serve as potential therapeutic targets for treating ovarian cancer.

PEO14 cells are known for their resistance to anti-cancer drugs, such as PTX, a chemotherapy agent commonly employed in treating ovarian cancer, despite its potential side effects. PTX, a member of the taxane class of drugs, is widely used as a chemotherapeutic agent for various cancers. Its mechanism of action involves the stabilization of microtubules within cells, thereby disrupting cell division and ultimately suppressing cancer cell growth [

19,

33,

34]]. Like many chemotherapeutic drugs, PTX induces various side effects, including neuropathy, nausea, and vomiting [

19,

35].

Therefore, combination therapy with acetylated APE1/Ref-1 and PTX may potentially reduce the side effects of PTX by increasing the chemosensitivity of cancer cells. This would allow the use of lower doses of PTX, potentially reducing the severity of side effects.

Considering the challenges posed by the lack of estrogen receptors and PTX resistance in PEO14 cells, a new treatment approach using a combination of rhAPE1/Ref-1 and aspirin was explored in this study. However, it is important to note that this study was conducted in cultured cells, so further research is needed to determine whether the acetylation of APE1/Ref-1 is an effective way to overcome PTX resistance in humans. Additionally, the potential for off-target effects and the specificity of the combined treatment in different cancer types remain unexplored. Furthermore, the long-term effects and potential toxicity of this combined therapy in a physiological environment are yet to be determined. Nevertheless, the results of this study are promising and suggest that this may be a new and effective approach for treating patients with PTX-resistant cancers. These aspects highlight the need for extensive in vivo studies and clinical trials to fully understand the therapeutic potential and safety profile of this novel approach

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.H.J.; methodology, J.H., Y.R.L., S.K, and H.J.Y.; formal analysis, J.H., Y.R.L, H.K.J., and C.S.K.; data curation, J.H. ,Y.R.L, E.O.L, and S.K.; writing-original draft preparation, Y.R.L, and B.H.J; writing-review and editing,B.H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Effect of recombinant human APE1/Ref-1 (rhAPE1/Ref-1) and aspirin (ASA) treatment on the viability of ovarian cancer cell lines and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). (A) Ovarian cancer cell lines PEO14 and CAOV-3, as well as HUVECs, were treated with varying concentrations of APE1/Ref-1 protein (0–5 µg/ml). After 24 h, cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. (B) PEO14 and CAOV-3 cells, along with HUVECs, were exposed to different concentrations of ASA (0–10 mM). After 24 h, cell viability was evaluated through MTT analysis. All data represent the mean ± SEM; n = 6. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple analysis. * P < 0.05 , **P < 0.01 vs. untreated group.

Figure 1.

Effect of recombinant human APE1/Ref-1 (rhAPE1/Ref-1) and aspirin (ASA) treatment on the viability of ovarian cancer cell lines and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). (A) Ovarian cancer cell lines PEO14 and CAOV-3, as well as HUVECs, were treated with varying concentrations of APE1/Ref-1 protein (0–5 µg/ml). After 24 h, cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. (B) PEO14 and CAOV-3 cells, along with HUVECs, were exposed to different concentrations of ASA (0–10 mM). After 24 h, cell viability was evaluated through MTT analysis. All data represent the mean ± SEM; n = 6. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple analysis. * P < 0.05 , **P < 0.01 vs. untreated group.

Figure 2.

Aspirin (ASA)-induced acetylation of recombinant human (rh)APE1/Ref-1 and hyperacetylation in PEO14 Cells. (A) In vitro acetylation of rhAPE1/Ref-1. In vitro co-incubation of ASA (3 mM) and rhAPE1/Ref-1 (1 μg/ml) for 24 h resulted in the ASA-induced acetylation of APE1/Ref-1. This was confirmed through immunoprecipitation with anti-APE1/Ref-1 antibodies and subsequent western blotting for acetyl-lysine. Sialic acid (SA) was included as a control, demonstrating the specificity of ASA-induced rhAPE1/Ref-1 acetylation under these conditions. (B) Hyperacetylation analysis of PEO14 cells. Using anti-acetyl-lysine antibodies, western blot analysis was performed on PEO14 cells treated with 3 mM ASA for 24 h to assess the hyperacetylation status.

Figure 2.

Aspirin (ASA)-induced acetylation of recombinant human (rh)APE1/Ref-1 and hyperacetylation in PEO14 Cells. (A) In vitro acetylation of rhAPE1/Ref-1. In vitro co-incubation of ASA (3 mM) and rhAPE1/Ref-1 (1 μg/ml) for 24 h resulted in the ASA-induced acetylation of APE1/Ref-1. This was confirmed through immunoprecipitation with anti-APE1/Ref-1 antibodies and subsequent western blotting for acetyl-lysine. Sialic acid (SA) was included as a control, demonstrating the specificity of ASA-induced rhAPE1/Ref-1 acetylation under these conditions. (B) Hyperacetylation analysis of PEO14 cells. Using anti-acetyl-lysine antibodies, western blot analysis was performed on PEO14 cells treated with 3 mM ASA for 24 h to assess the hyperacetylation status.

Figure 3.

Co-treatment of rhAPE1/Ref-1 with aspirin (ASA) decreases the cell viability of ovarian cancer cells. Ovarian cancer cell lines PEO14 and CAOV-3 and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (1×105 cells/ml) were co-treated with ASA (3 mM) and varying concentrations of rhAPE1/Ref-1. Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay after 24 h. MTT analysis was independently conducted five or six times in triplicate. All values represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple analysis. **P < 0.01 vs. the control group (Con).

Figure 3.

Co-treatment of rhAPE1/Ref-1 with aspirin (ASA) decreases the cell viability of ovarian cancer cells. Ovarian cancer cell lines PEO14 and CAOV-3 and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (1×105 cells/ml) were co-treated with ASA (3 mM) and varying concentrations of rhAPE1/Ref-1. Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay after 24 h. MTT analysis was independently conducted five or six times in triplicate. All values represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple analysis. **P < 0.01 vs. the control group (Con).

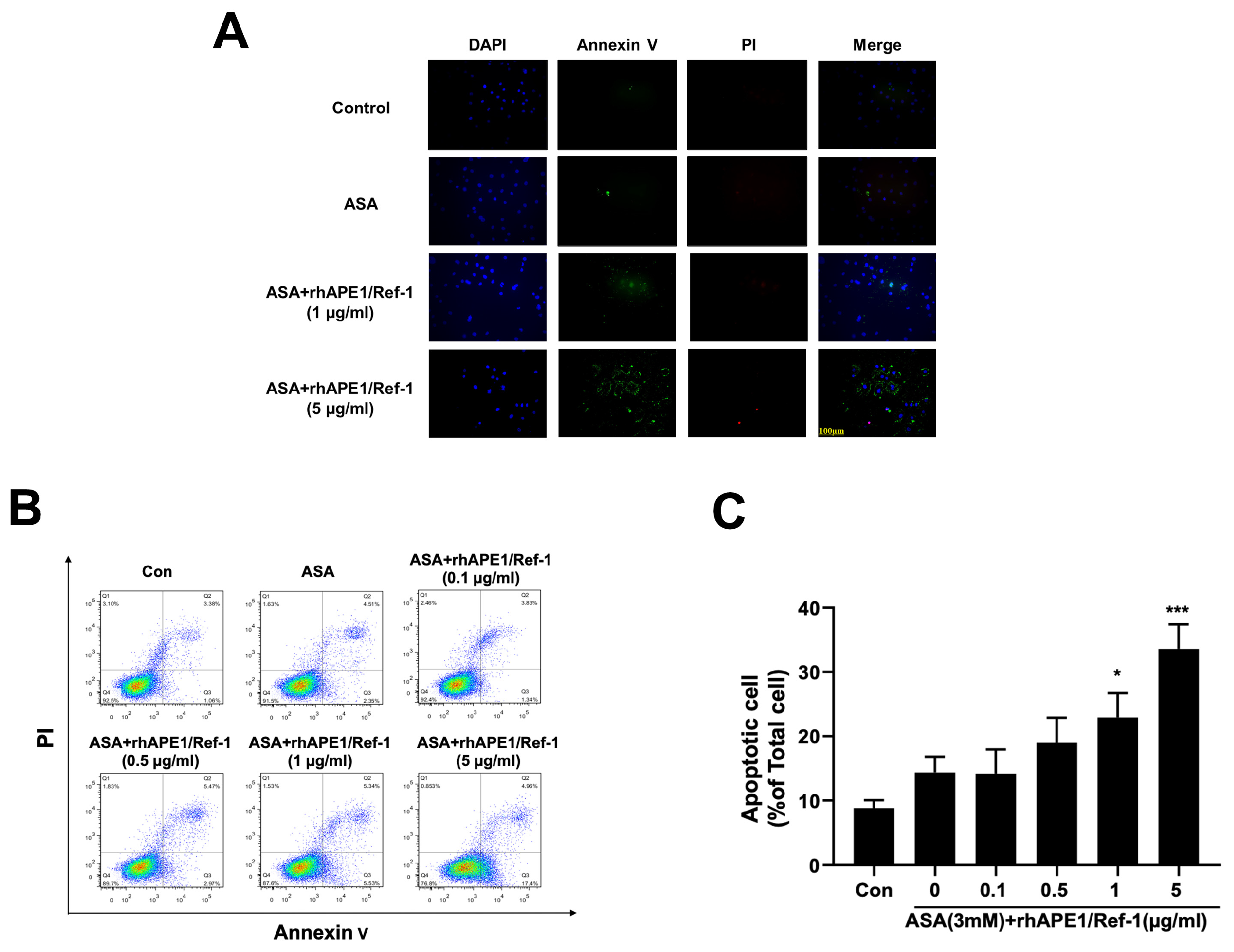

Figure 4.

Induction of apoptosis in PEO14 cells upon co-treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 and aspirin (ASA). (A) Immunofluorescence staining of PEO14 cells incubated with ASA (3 mM) or rhAPE1/Ref-1 at the indicated concentrations. Cell apoptosis was assessed through DAPI, Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and propidium iodide (PI) triple fluorescence staining. Annexin V-FITC and PI signals were barely detectable in the control and ASA-treated cells. However, strong fluorescence was observed in response to treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 (5 µg/ml) and ASA. Scale bar =100µm. (B) Flow cytometry analysis was employed to quantify apoptotic cell death in PEO14 cells exposed to rhAPE1/Ref-1 at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 5 µg/ml in combination with aspirin (3 mM) for 24 h. (C) The percentage of total apoptotic cells, including both early and late apoptosis (Q2+Q3), was determined using flow cytometry. All values represent the mean ± SEM; n = 3. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple analysis. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005 vs. the control group (Con).

Figure 4.

Induction of apoptosis in PEO14 cells upon co-treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 and aspirin (ASA). (A) Immunofluorescence staining of PEO14 cells incubated with ASA (3 mM) or rhAPE1/Ref-1 at the indicated concentrations. Cell apoptosis was assessed through DAPI, Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and propidium iodide (PI) triple fluorescence staining. Annexin V-FITC and PI signals were barely detectable in the control and ASA-treated cells. However, strong fluorescence was observed in response to treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 (5 µg/ml) and ASA. Scale bar =100µm. (B) Flow cytometry analysis was employed to quantify apoptotic cell death in PEO14 cells exposed to rhAPE1/Ref-1 at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 5 µg/ml in combination with aspirin (3 mM) for 24 h. (C) The percentage of total apoptotic cells, including both early and late apoptosis (Q2+Q3), was determined using flow cytometry. All values represent the mean ± SEM; n = 3. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple analysis. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005 vs. the control group (Con).

Figure 5.

Induction of caspase-3/7 activation and PARP cleavage in PEO14 Cells upon co-treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 and aspirin (ASA). (A) PEO14 cells were treated with ASA alone or rhAPE1/Ref-1 in combination with ASA. After 24 h, the degree of caspase-3/7 activation was measured using the Caspase-Glo® 3/7 assay. All values represent the mean ± SEM; n = 3. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple analysis: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the control group (Con). (B) Western blot analysis of cleaved PARP. Representative data from the western blot results illustrate an increase in the expression of cleaved PARP (90 kDa) in PEO14 ovarian cancer cells treated with rhAPE1/Ref-1 (≥0.5 µg/ml) in combination with ASA (upper panel). Notably, rhAPE1/Ref-1 with ASA did not induce PARP cleavage in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (bottom panel).

Figure 5.

Induction of caspase-3/7 activation and PARP cleavage in PEO14 Cells upon co-treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 and aspirin (ASA). (A) PEO14 cells were treated with ASA alone or rhAPE1/Ref-1 in combination with ASA. After 24 h, the degree of caspase-3/7 activation was measured using the Caspase-Glo® 3/7 assay. All values represent the mean ± SEM; n = 3. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple analysis: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the control group (Con). (B) Western blot analysis of cleaved PARP. Representative data from the western blot results illustrate an increase in the expression of cleaved PARP (90 kDa) in PEO14 ovarian cancer cells treated with rhAPE1/Ref-1 (≥0.5 µg/ml) in combination with ASA (upper panel). Notably, rhAPE1/Ref-1 with ASA did not induce PARP cleavage in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (bottom panel).

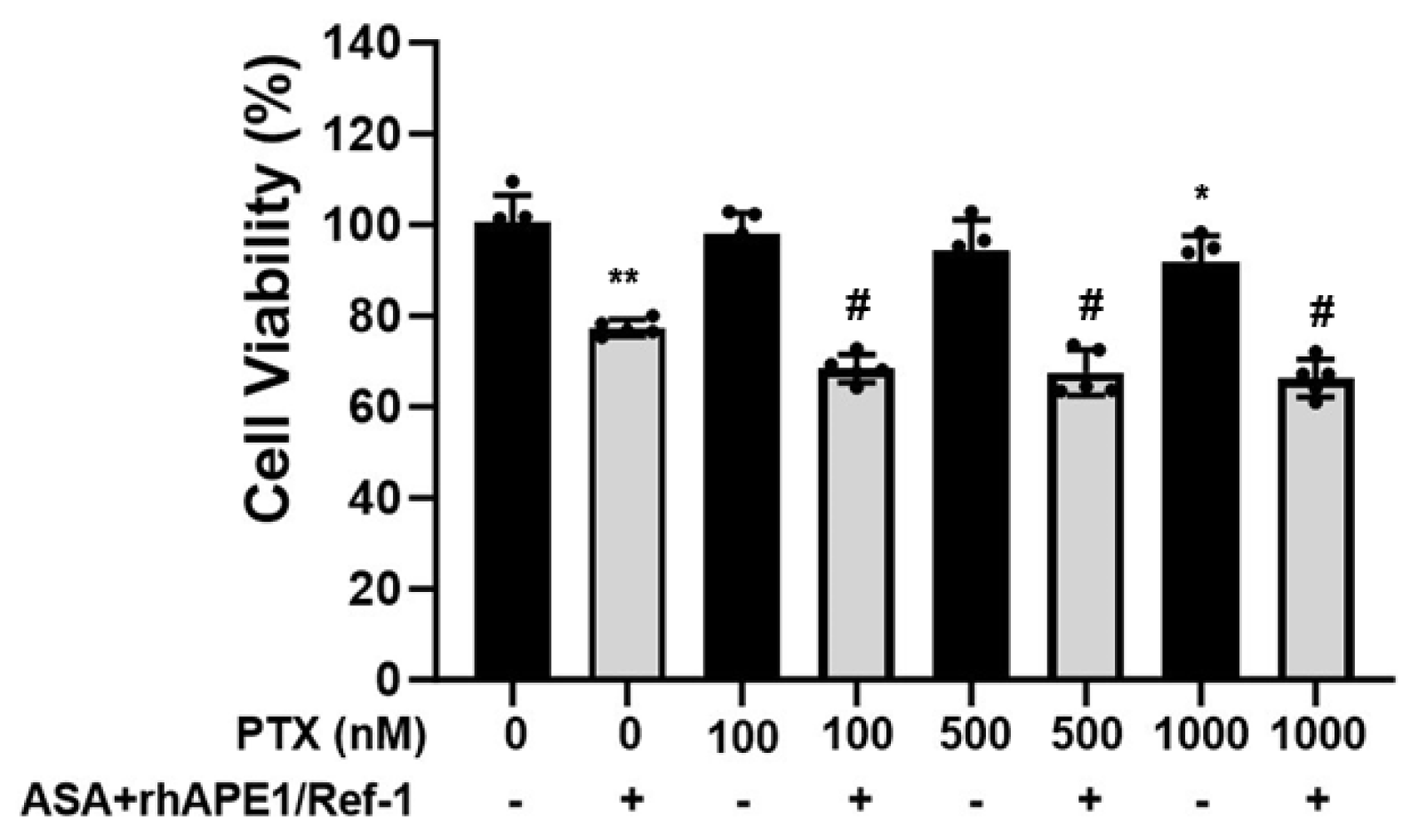

Figure 6.

Enhanced anti-cancer efficacy of paclitaxel in PEO14 ovarian cancer cells upon co-treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 and aspirin (ASA). PEO14 cells were exposed to a range of paclitaxel concentrations (100–1000 nM) with or without simultaneous treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 (1 µg/ml) and ASA (3 mM). MTT assays revealed that paclitaxel alone induced a modest level of cell death (2–8%) after 24 hours, indicating the inherent resistance of PEO14 cells. A significant enhancement in the anti-cancer treatment efficacy of paclitaxel in PEO14 cells was observed upon co-treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 and ASA. All values represent the mean ± SEM; n = 5. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. untreated group, #P < 0.01 vs. the ASA+rhAPE1/Ref-1-treated group.

Figure 6.

Enhanced anti-cancer efficacy of paclitaxel in PEO14 ovarian cancer cells upon co-treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 and aspirin (ASA). PEO14 cells were exposed to a range of paclitaxel concentrations (100–1000 nM) with or without simultaneous treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 (1 µg/ml) and ASA (3 mM). MTT assays revealed that paclitaxel alone induced a modest level of cell death (2–8%) after 24 hours, indicating the inherent resistance of PEO14 cells. A significant enhancement in the anti-cancer treatment efficacy of paclitaxel in PEO14 cells was observed upon co-treatment with rhAPE1/Ref-1 and ASA. All values represent the mean ± SEM; n = 5. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. untreated group, #P < 0.01 vs. the ASA+rhAPE1/Ref-1-treated group.