Submitted:

01 February 2024

Posted:

01 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

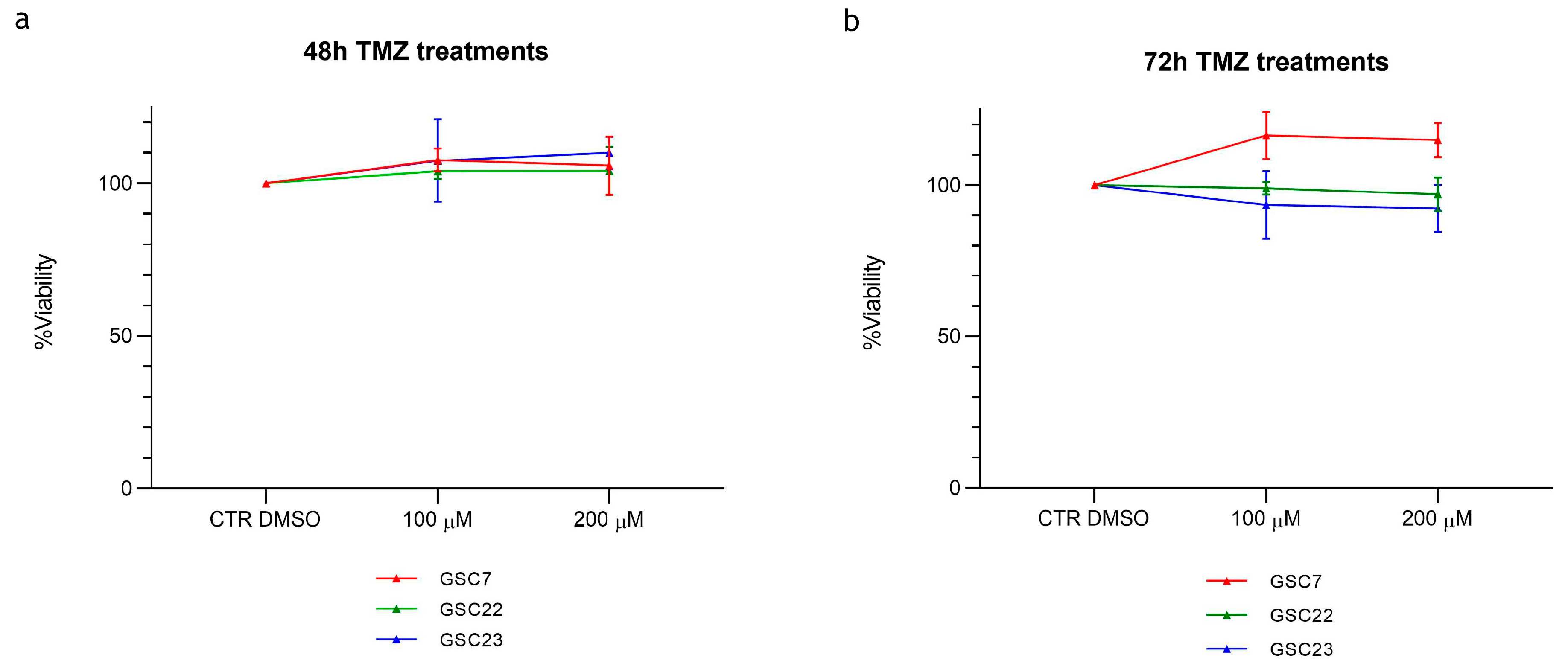

2.1. Sensitivity of glioma stem cell lines to temozolomide in vitro is largely independent of MGMT promoter methylation

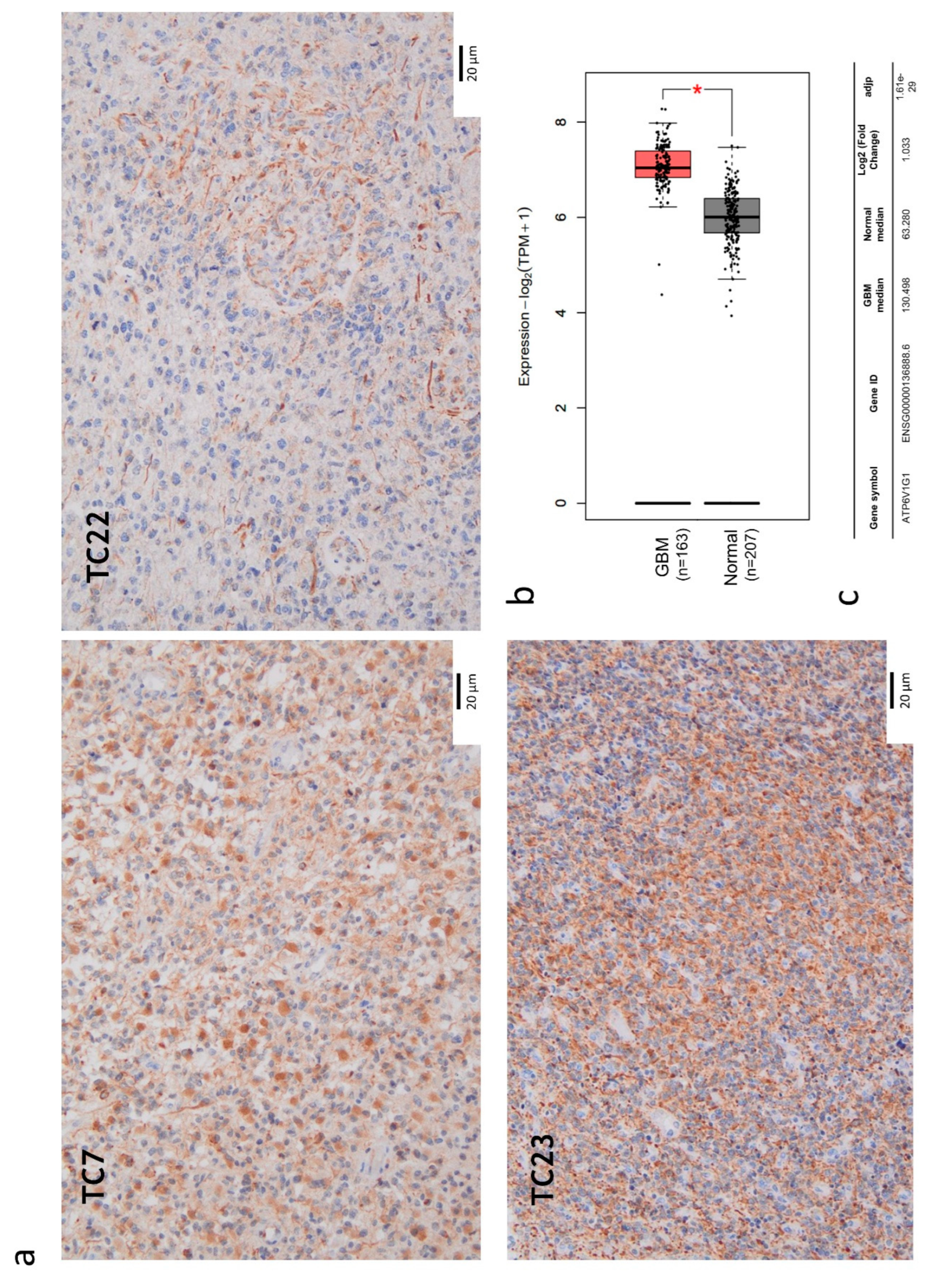

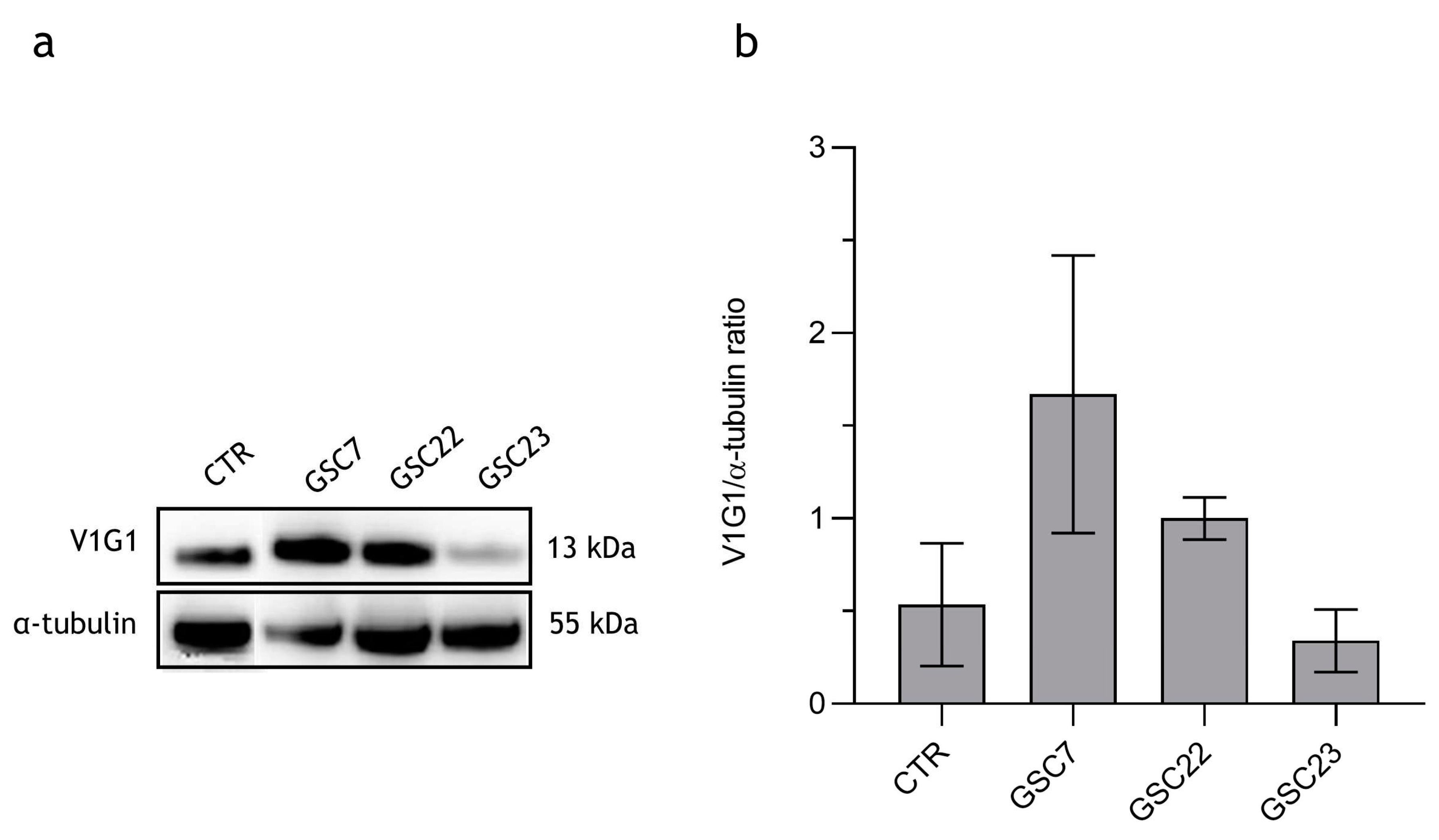

2.3. V-ATPase is overexpressed in tumor core bulks and GSC lines

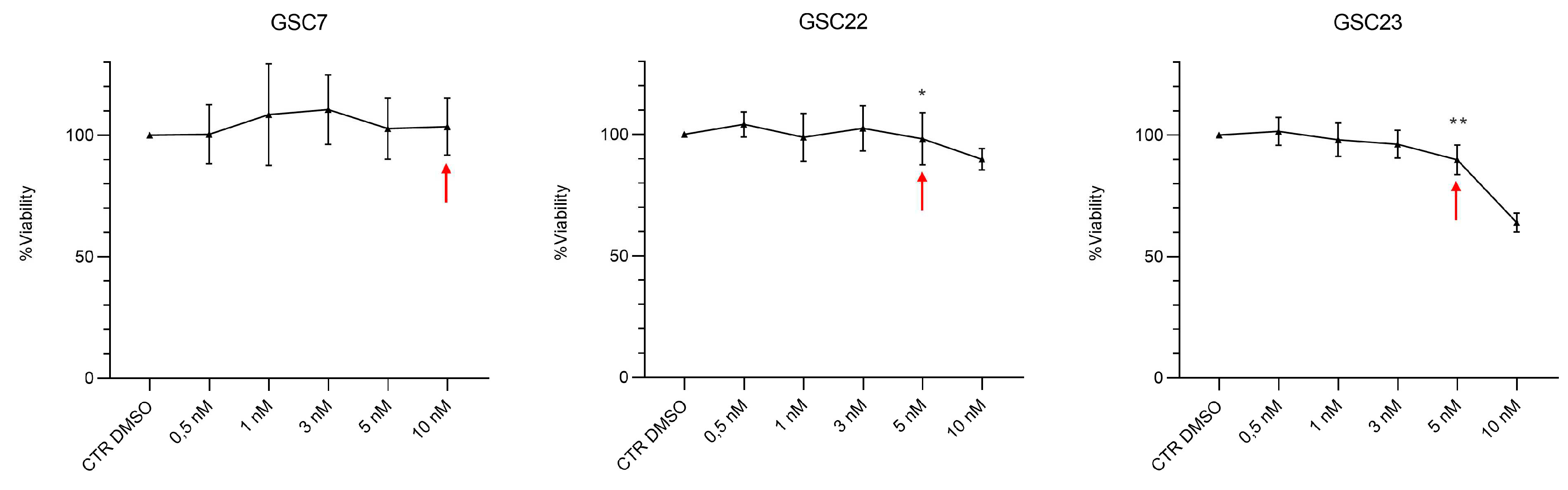

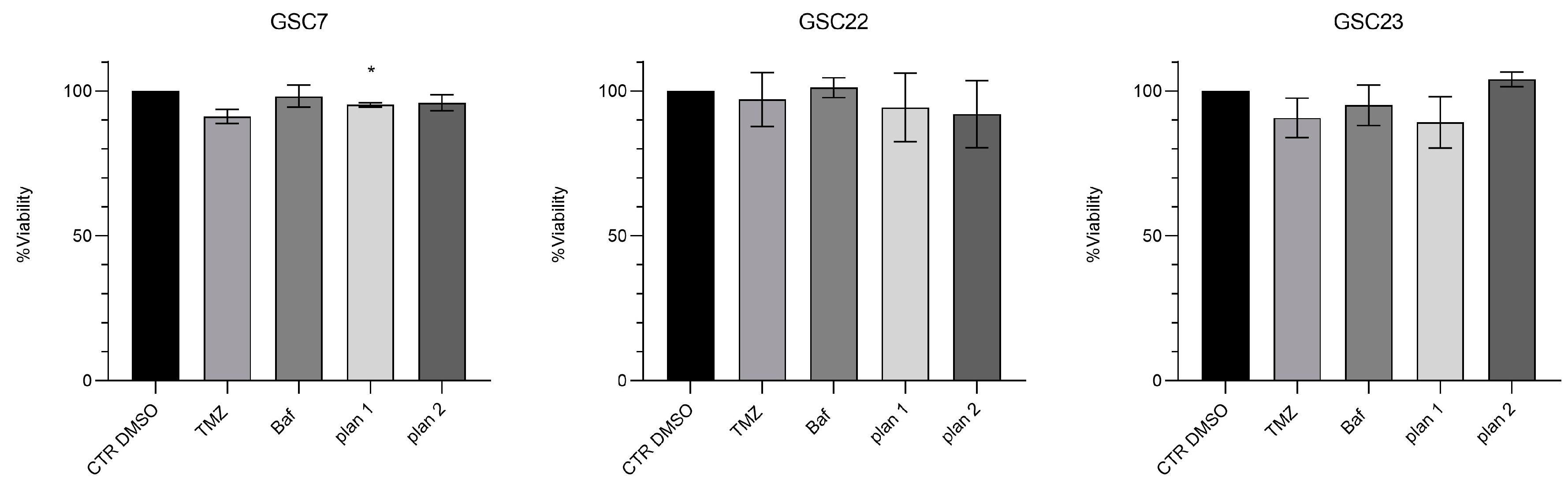

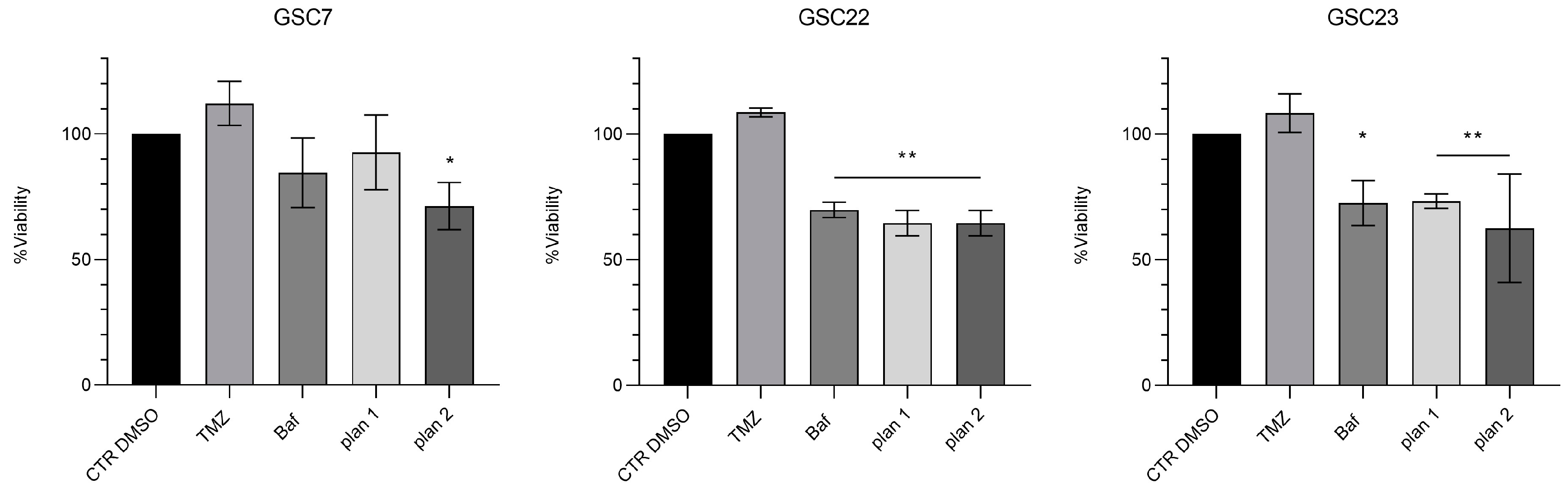

2.4. Nanomolar doses of bafilomycin A1 do not overcome temozolomide resistance in GSC lines

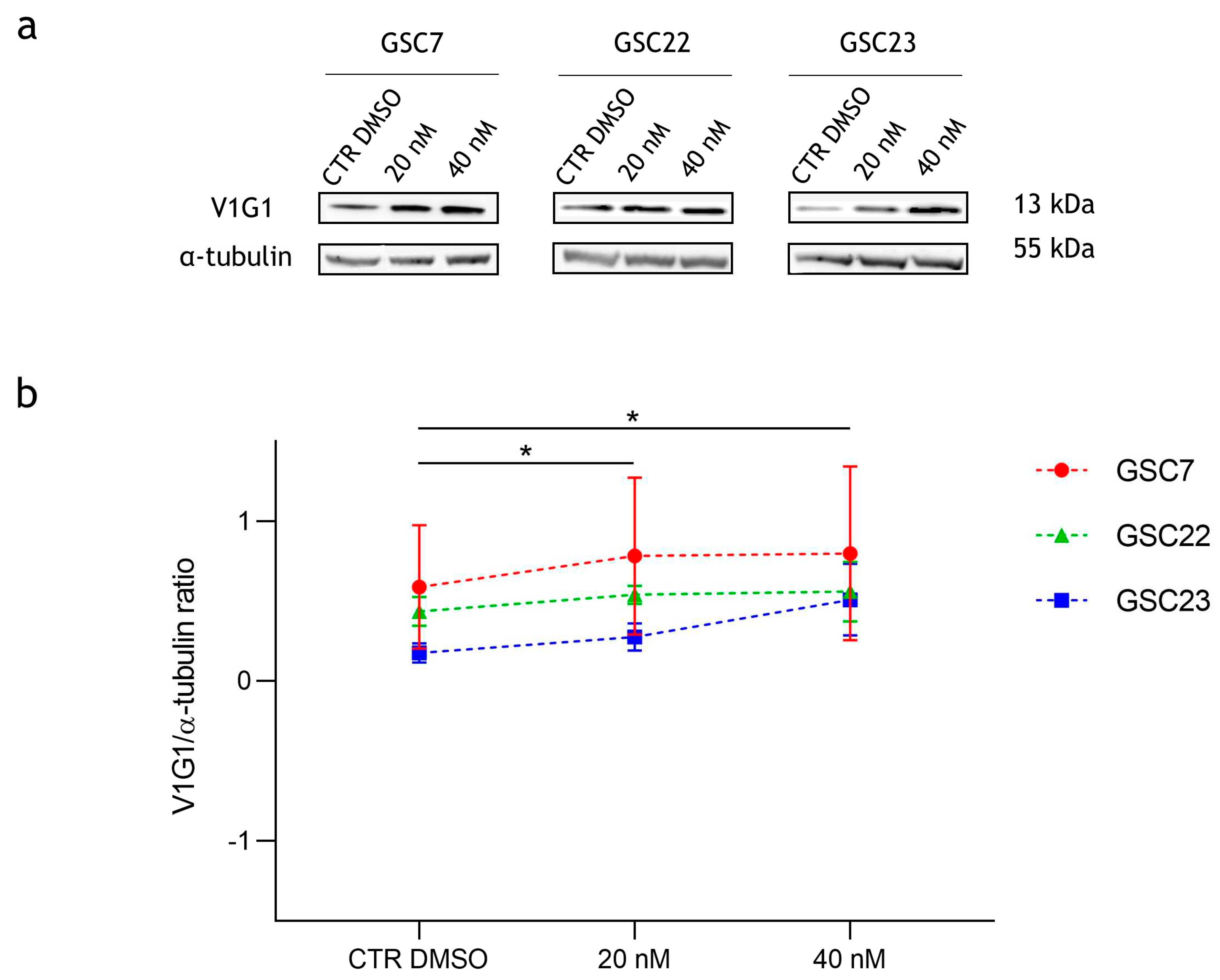

2.5. Effect of bafilomycin A1 treatment on V-ATPase protein expression

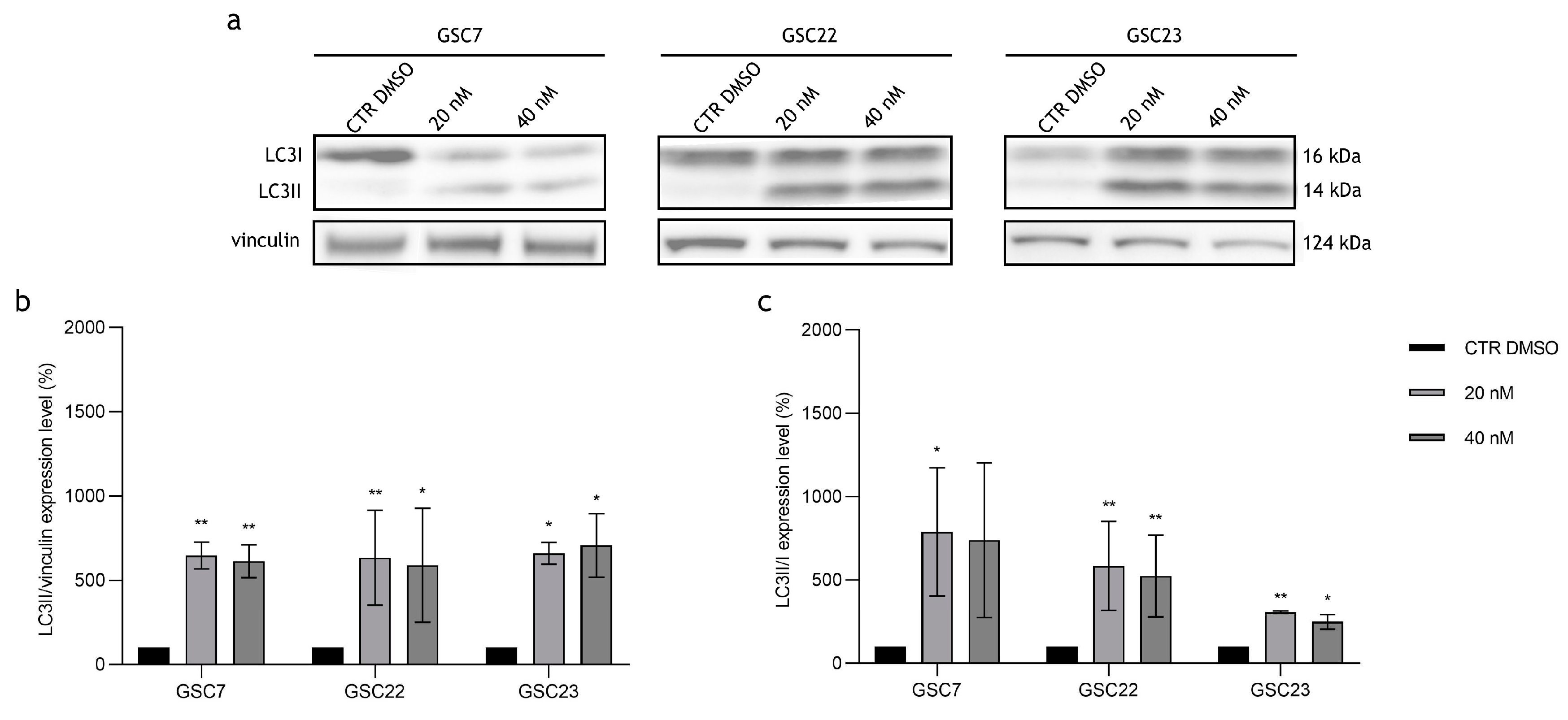

2.6. Autophagy pathway in GSC lines is blocked by bafilomycin A1

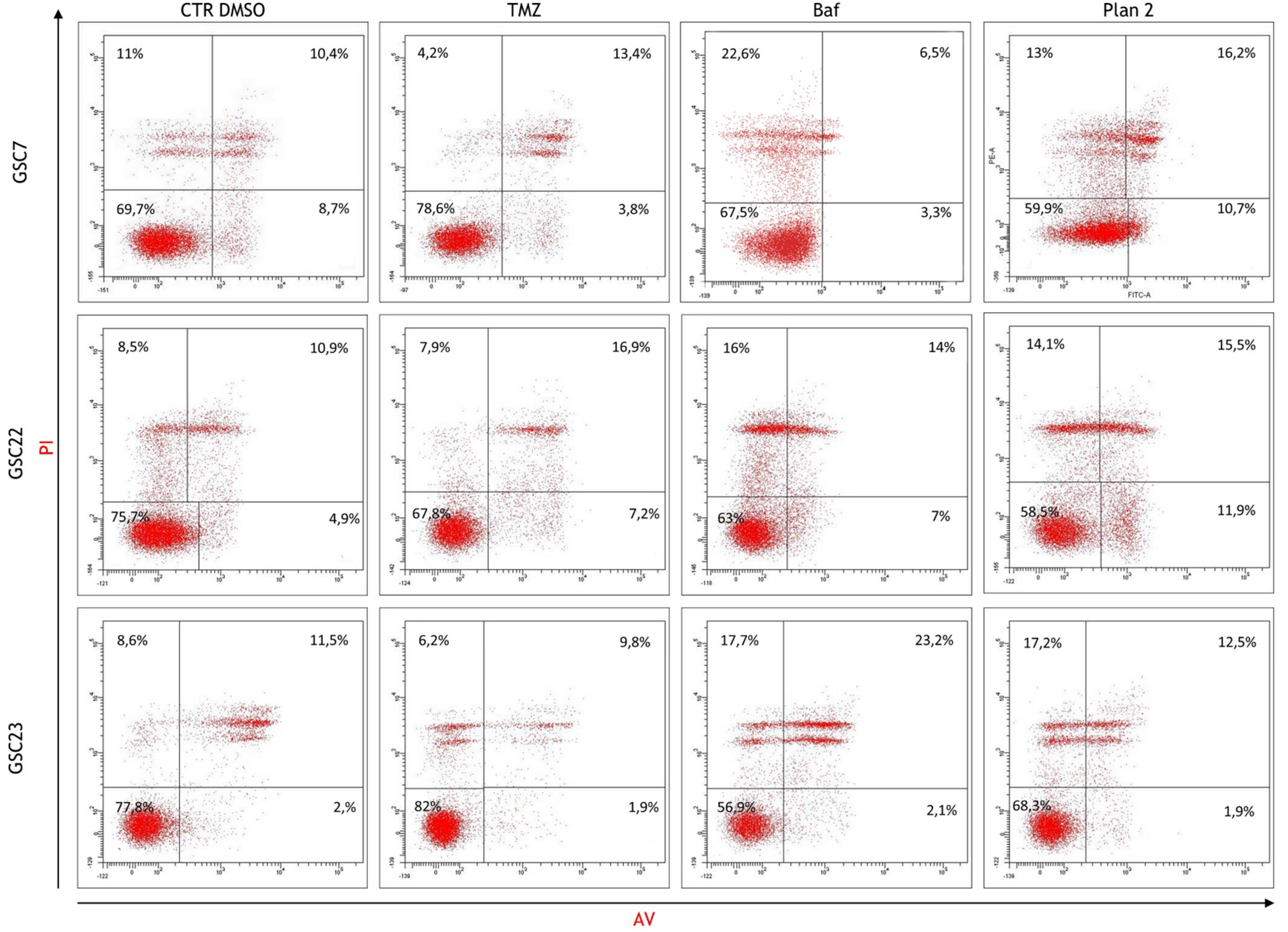

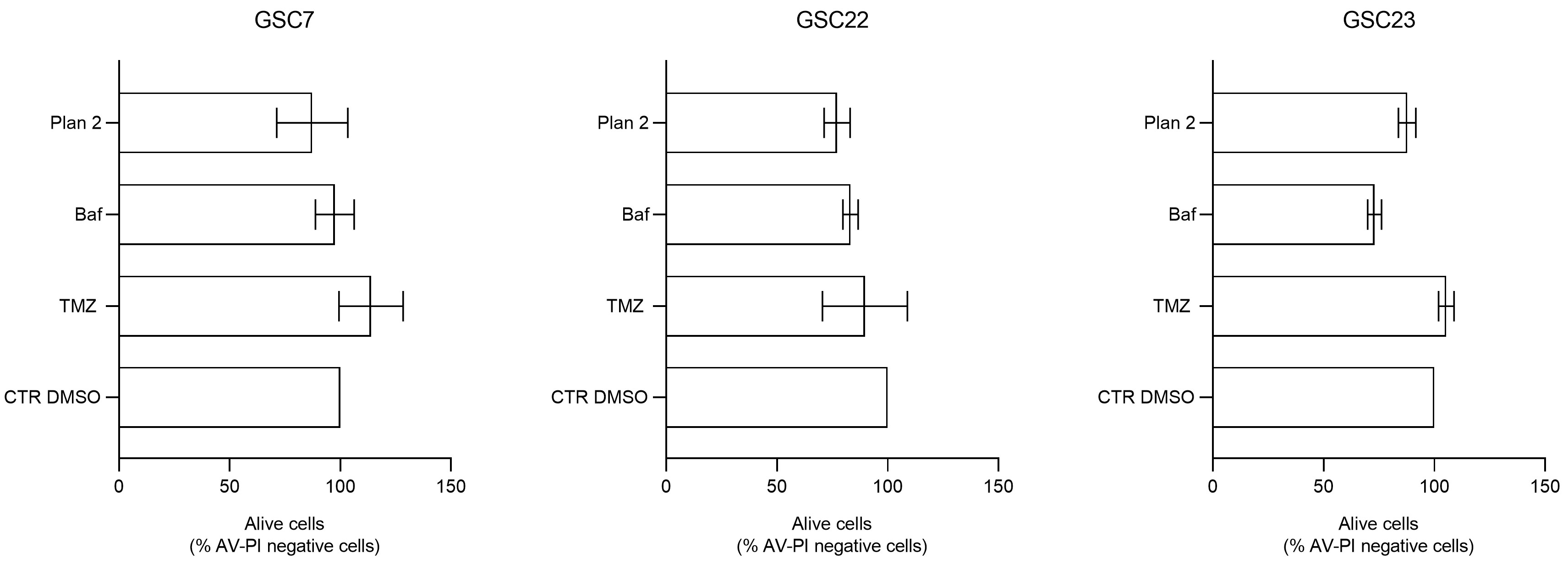

2.7. Bafilomycin A1 induces necrosis in GSC lines

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patient-derived specimens

4.2. Cytotoxicity assay

4.3. MGMT Methylation Analysis

4.4. Immunohistochemistry

4.5. Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2 platform consultation

4.6. Western blotting

4.7. Flow cytometry

4.8. Statistical analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A Summary. Neuro Oncol 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cote, D.J.; Ascha, M.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Adult Glioma Incidence and Survival by Race or Ethnicity in the United States From 2000 to 2014. JAMA Oncol 2018, 4, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Witt Hamer, P.C.; Robles, S.G.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Duffau, H.; Berger, M.S. Impact of Intraoperative Stimulation Brain Mapping on Glioma Surgery Outcome: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30, 2559–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinaro, A.M.; Hervey-Jumper, S.; Morshed, R.A.; Young, J.; Han, S.J.; Chunduru, P.; Zhang, Y.; Phillips, J.J.; Shai, A.; Lafontaine, M.; et al. Association of Maximal Extent of Resection of Contrast-Enhanced and Non-Contrast-Enhanced Tumor With Survival Within Molecular Subgroups of Patients With Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. JAMA Oncol 2020, 6, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegi, M.E.; Diserens, A.-C.; Gorlia, T.; Hamou, M.-F.; de Tribolet, N.; Weller, M.; Kros, J.M.; Hainfellner, J.A.; Mason, W.; Mariani, L.; et al. MGMT Gene Silencing and Benefit from Temozolomide in Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005, 352, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Hegi, M.E.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Janzer, R.C.; Ludwin, S.K.; Allgeier, A.; Fisher, B.; Belanger, K.; et al. Effects of Radiotherapy with Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide versus Radiotherapy Alone on Survival in Glioblastoma in a Randomised Phase III Study: 5-Year Analysis of the EORTC-NCIC Trial. Lancet Oncol 2009, 10, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegi, M.E.; Genbrugge, E.; Gorlia, T.; Stupp, R.; Gilbert, M.R.; Chinot, O.L.; Nabors, L.B.; Jones, G.; Van Criekinge, W.; Straub, J.; et al. MGMT Promoter Methylation Cutoff with Safety Margin for Selecting Glioblastoma Patients into Trials Omitting Temozolomide: A Pooled Analysis of Four Clinical Trials. Clin Cancer Res 2019, 25, 1809–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Taillibert, S.; Kanner, A.; Read, W.; Steinberg, D.; Lhermitte, B.; Toms, S.; Idbaih, A.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Fink, K.; et al. Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Maintenance Temozolomide vs Maintenance Temozolomide Alone on Survival in Patients With Glioblastoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 2306–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambra, M.; Di Cristofori, A.; Valtorta, S.; Manfrellotti, R.; Bigiogera, V.; Basso, G.; Moresco, R.M.; Giussani, C.; Bentivegna, A. The Peritumoral Brain Zone in Glioblastoma: Where We Are and Where We Are Going. J Neurosci Res 2023, 101, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, T.; Howard, C.M.; Yu, A.; Xu, L.; Aziz, K.; Jho, D.; Leonardo, J.; Hameed, M.A.; Karlovits, S.M.; Wegner, R.E.; et al. Cancer Stem Cell Chemotherapeutics Assay for Prospective Treatment of Recurrent Glioblastoma and Progressive Anaplastic Glioma: A Single-Institution Case Series. Transl Oncol 2020, 13, 100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, T.; Sengupta, S.; Glantz, M.J.; Green, R.M.; Yu, A.; Aregawi, D.; Chaudhary, R.; Chen, R.; Zuccarello, M.; Lu-Emerson, C.; et al. Cancer Stem Cell Assay-Guided Chemotherapy Improves Survival of Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma in a Randomized Trial. Cell Rep Med 2023, 4, 101025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fais, S.; De Milito, A.; You, H.; Qin, W. Targeting Vacuolar H+-ATPases as a New Strategy against Cancer. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 10627–10630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgac, M. A New Twist to V-ATPases and Cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 31793–31794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciani, F.; Spada, M.; De Milito, A.; Molinari, A.; Rivoltini, L.; Montinaro, A.; Marra, M.; Lugini, L.; Logozzi, M.; Lozupone, F.; et al. Effect of Proton Pump Inhibitor Pretreatment on Resistance of Solid Tumors to Cytotoxic Drugs. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004, 96, 1702–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, C.; Cotter, K.; Stransky, L.; Forgac, M. Regulation of V-ATPase Assembly and Function of V-ATPases in Tumor Cell Invasiveness. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1857, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stransky, L.; Cotter, K.; Forgac, M. The Function of V-ATPases in Cancer. Physiol Rev 2016, 96, 1071–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sayáns, M.; Somoza-Martín, J.M.; Barros-Angueira, F.; Rey, J.M.G.; García-García, A. V-ATPase Inhibitors and Implication in Cancer Treatment. Cancer Treat Rev 2009, 35, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rofstad, E.K.; Mathiesen, B.; Kindem, K.; Galappathi, K. Acidic Extracellular pH Promotes Experimental Metastasis of Human Melanoma Cells in Athymic Nude Mice. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 6699–6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, M.; Zou, Y.; Jin, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Mechanisms of Chemotherapeutic Resistance and the Application of Targeted Nanoparticles for Enhanced Chemotherapy in Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharzadeh, M.R.; Barar, J.; Pourseif, M.M.; Eskandani, M.; Jafari Niya, M.; Mashayekhi, M.R.; Omidi, Y. Molecular Machineries of pH Dysregulation in Tumor Microenvironment: Potential Targets for Cancer Therapy. Bioimpacts 2017, 7, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessio, A.; Proietti, G.; Sica, G.; Scicchitano, B.M. Pathological and Molecular Features of Glioblastoma and Its Peritumoral Tissue. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persano, L.; Rampazzo, E.; Della Puppa, A.; Pistollato, F.; Basso, G. The Three-Layer Concentric Model of Glioblastoma: Cancer Stem Cells, Microenvironmental Regulation, and Therapeutic Implications. ScientificWorldJournal 2011, 11, 1829–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, I.; Storaci, A.M.; Terrasi, A.; Di Cristofori, A.; Locatelli, M.; Caroli, M.; Ferrero, S.; Altieri, D.C.; Vaira, V. Interplay between V-ATPase G1 and Small EV-miRNAs Modulates ERK1/2 Activation in GBM Stem Cells and Non-Neoplastic Milieu. Mol Cancer Res 2020, 18, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, I.; Terrasi, A.; Martelli, C.; Gaudioso, G.; Di Cristofori, A.; Storaci, A.M.; Formica, M.; Braidotti, P.; Todoerti, K.; Ferrero, S.; et al. A GBM-like V-ATPase Signature Directs Cell-Cell Tumor Signaling and Reprogramming via Large Oncosomes. EBioMedicine 2019, 41, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillon, E.; Farion, R.; Reuveni, M.; Glidle, A.; Rémy, C.; Coles, J.A. Spatial Profiles of Markers of Glycolysis, Mitochondria, and Proton Pumps in a Rat Glioma Suggest Coordinated Programming for Proliferation. BMC Res Notes 2015, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Lei, L.; Hu, J.; Wang, G.; Liu, J.; Ou, S. Identification of a Five-Gene Signature Deriving from the Vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase) Sub-Classifies Gliomas and Decides Prognoses and Immune Microenvironment Alterations. Cell Cycle 2022, 21, 1294–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrasi, A.; Bertolini, I.; Martelli, C.; Gaudioso, G.; Di Cristofori, A.; Storaci, A.M.; Formica, M.; Bosari, S.; Caroli, M.; Ottobrini, L.; et al. Specific V-ATPase Expression Sub-Classifies IDHwt Lower-Grade Gliomas and Impacts Glioma Growth in Vivo. EBioMedicine 2019, 41, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cristofori, A.; Ferrero, S.; Bertolini, I.; Gaudioso, G.; Russo, M.V.; Berno, V.; Vanini, M.; Locatelli, M.; Zavanone, M.; Rampini, P.; et al. The Vacuolar H+ ATPase Is a Novel Therapeutic Target for Glioblastoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 17514–17531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auffinger, B.; Spencer, D.; Pytel, P.; Ahmed, A.U.; Lesniak, M.S. The Role of Glioma Stem Cells in Chemotherapy Resistance and Glioblastoma Multiforme Recurrence. Expert Rev Neurother 2015, 15, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supino, R.; Scovassi, A.I.; Croce, A.C.; Dal Bo, L.; Favini, E.; Corbelli, A.; Farina, C.; Misiano, P.; Zunino, F. Biological Effects of a New Vacuolar-H,-ATPase Inhibitor in Colon Carcinoma Cell Lines. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009, 1171, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, E.J.; Siebers, A.; Altendorf, K. Bafilomycins: A Class of Inhibitors of Membrane ATPases from Microorganisms, Animal Cells, and Plant Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988, 85, 7972–7976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, N.; Song, L.; Zhang, S.; Lin, W.; Cao, Y.; Xu, F.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; et al. Bafilomycin A1 Targets Both Autophagy and Apoptosis Pathways in Pediatric B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Haematologica 2015, 100, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeya, Y.; Mizushima, N.; Ueno, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Kirisako, T.; Noda, T.; Kominami, E.; Ohsumi, Y.; Yoshimori, T. LC3, a Mammalian Homologue of Yeast Apg8p, Is Localized in Autophagosome Membranes after Processing. EMBO J 2000, 19, 5720–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eramo, A.; Ricci-Vitiani, L.; Zeuner, A.; Pallini, R.; Lotti, F.; Sette, G.; Pilozzi, E.; Larocca, L.M.; Peschle, C.; De Maria, R. Chemotherapy Resistance of Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Cell Death Differ 2006, 13, 1238–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, B.; Southgate, T.D.; Gilham, D.E.; Margison, G.P. O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase Inactivation and Chemotherapy. Br Med Bull 2008, 85, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Miner, A.; Hennis, L.; Mittal, S. Mechanisms of Temozolomide Resistance in Glioblastoma - a Comprehensive Review. Cancer Drug Resist 2021, 4, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalamarty, S.S.K.; Filipczak, N.; Li, X.; Subhan, M.A.; Parveen, F.; Ataide, J.A.; Rajmalani, B.A.; Torchilin, V.P. Mechanisms of Resistance and Current Treatment Options for Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM). Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Gueble, S.E.; Sundaram, R.K.; Huseman, E.D.; Bindra, R.S.; Herzon, S.B. Mechanism-Based Design of Agents That Selectively Target Drug-Resistant Glioma. Science 2022, 377, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stritzelberger, J.; Distel, L.; Buslei, R.; Fietkau, R.; Putz, F. Acquired Temozolomide Resistance in Human Glioblastoma Cell Line U251 Is Caused by Mismatch Repair Deficiency and Can Be Overcome by Lomustine. Clin Transl Oncol 2018, 20, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Stevens, M.F.G.; Bradshaw, T.D. Temozolomide: Mechanisms of Action, Repair and Resistance. Curr Mol Pharmacol 2012, 5, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.P.; Forgac, M. Regulation and Function of V-ATPases in Physiology and Disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2020, 1862, 183341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Kang, R.; Liu, J.; Tang, D. The V-ATPases in Cancer and Cell Death. Cancer Gene Ther 2022, 29, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiapaer, S.; Furuta, T.; Tanaka, S.; Kitabayashi, T.; Nakada, M. Potential Strategies Overcoming the Temozolomide Resistance for Glioblastoma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2018, 58, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmoto, A.; Yachida, S. Current Status of Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors and Future Directions. Onco Targets Ther 2017, 10, 5195–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzawa, T.; Germano, I.M.; Komata, T.; Ito, H.; Kondo, Y.; Kondo, S. Role of Autophagy in Temozolomide-Induced Cytotoxicity for Malignant Glioma Cells. Cell Death Differ 2004, 11, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, T.; Yoshimori, T.; Henomatsu, N.; Tashiro, Y. Inhibitors of Vacuolar-Type H(+)-ATPase Suppresses Proliferation of Cultured Cells. J Cell Physiol 1993, 157, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, L.T.H.; Sari, I.N.; Yang, Y.-G.; Lee, S.-H.; Jun, N.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, Y.K.; Kwon, H.Y. Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) in Drug Resistance and Their Therapeutic Implications in Cancer Treatment. Stem Cells Int 2018, 2018, 5416923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.C.; Kishony, R. Opposing Effects of Target Overexpression Reveal Drug Mechanisms. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambra, M.; Messuti, E.; Di Cristofori, A.; Cavandoli, C.; Bruno, R.; Buonanno, R.; Marzorati, M.; Zambuto, M.; Rodriguez-Menendez, V.; Redaelli, S.; et al. Characterizing the Genomic Profile in High-Grade Gliomas: From Tumor Core to Peritumoral Brain Zone, Passing through Glioma-Derived Tumorspheres. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, F.; Sahnane, N.; Cerutti, R.; Cipriani, D.; Barizzi, J.; Stefanini, F.M.; Epistolio, S.; Cerati, M.; Balbi, S.; Mazzucchelli, L.; et al. The Impact of Surgery in IDH 1 Wild Type Glioblastoma in Relation With the MGMT Deregulation. Front Oncol 2020, 9, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malacrida, A.; Di Domizio, A.; Bentivegna, A.; Cislaghi, G.; Messuti, E.; Tabano, S.M.; Giussani, C.; Zuliani, V.; Rivara, M.; Nicolini, G. MV1035 Overcomes Temozolomide Resistance in Patient-Derived Glioblastoma Stem Cell Lines. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Kang, B.; Li, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: An Enhanced Web Server for Large-Scale Expression Profiling and Interactive Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, W556–W560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient | % of methylation | Status | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TC | GSC | ||

| 7 | 1% | 10% | - |

| 22 | 17% | 78% | + |

| 23 | 38% | 41% | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).