Submitted:

31 January 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.1. Materials

2.2. Molecular Identification of Strains

2.2.1. 16S rDNA Identification

2.2.2. gryB gene Identification

2.3. Determination of Siderophore-Producing Activity

2.3.1. Quantitative and Qualitative Measurements

Identification of the Type of Ferrophilin Chelating Groups

2.4. Indole-Acetic Acid Production, GA, CTK Capacity

2.5. Phosphate Solubilization and Potassium Release Capacity

2.6. Determination of Cd2+ Tolerance

2.7. Effect of Strains on Ryegrass Growth under Cd2+ Stress

2.7.1. Determination of Cd2+ Effects on Ryegrass Seed Germination

2.7.2. The Effect of the Strain on Ryegrass Growth under Cd2+ Stress

2.7.3. The Effects of the Strain on Physiological Indicators of Ryegrass under Cd2+ Stress

2.8. Whole Genome Sequencing

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

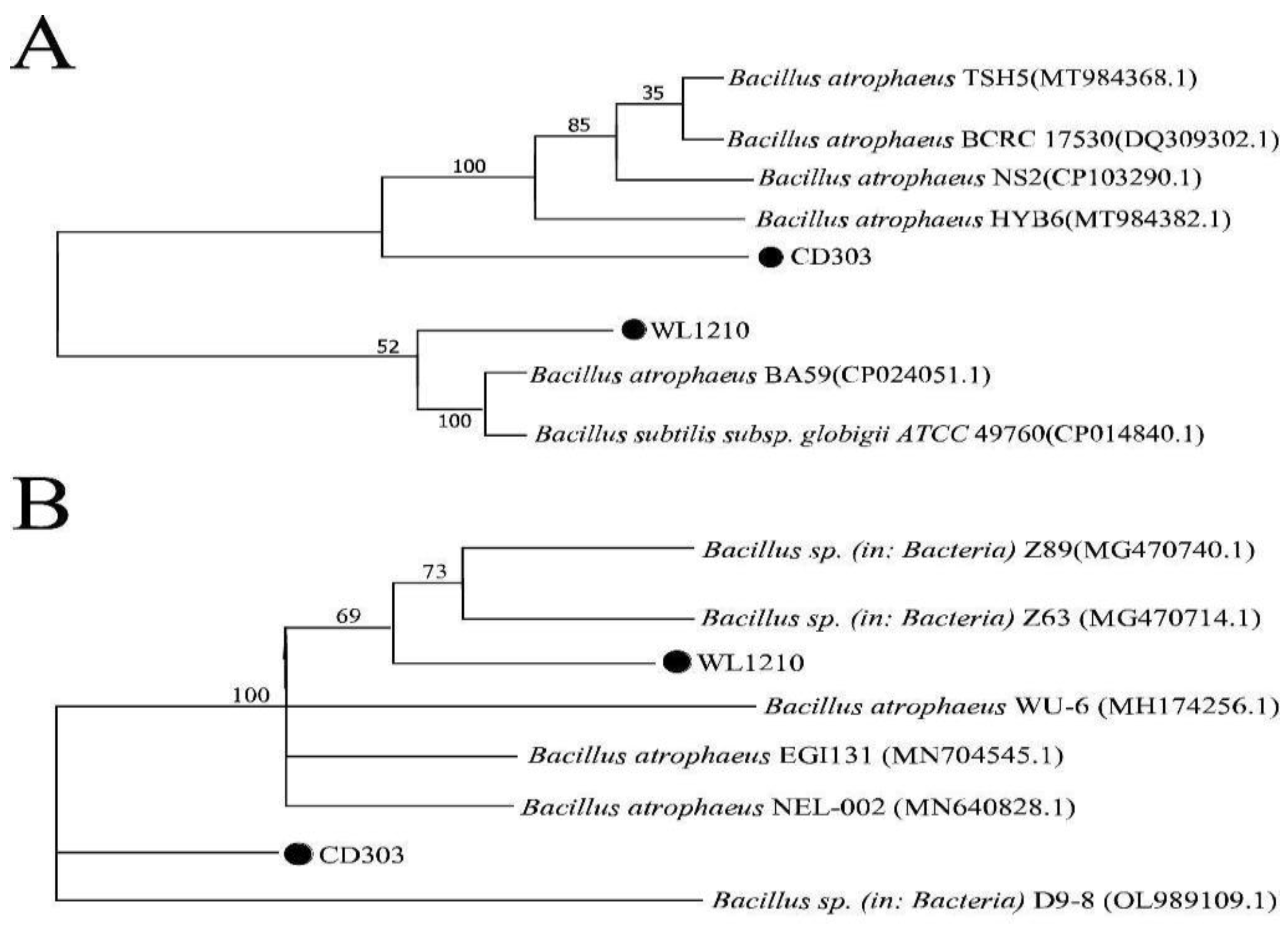

3.1. Molecular Characterization of Strains

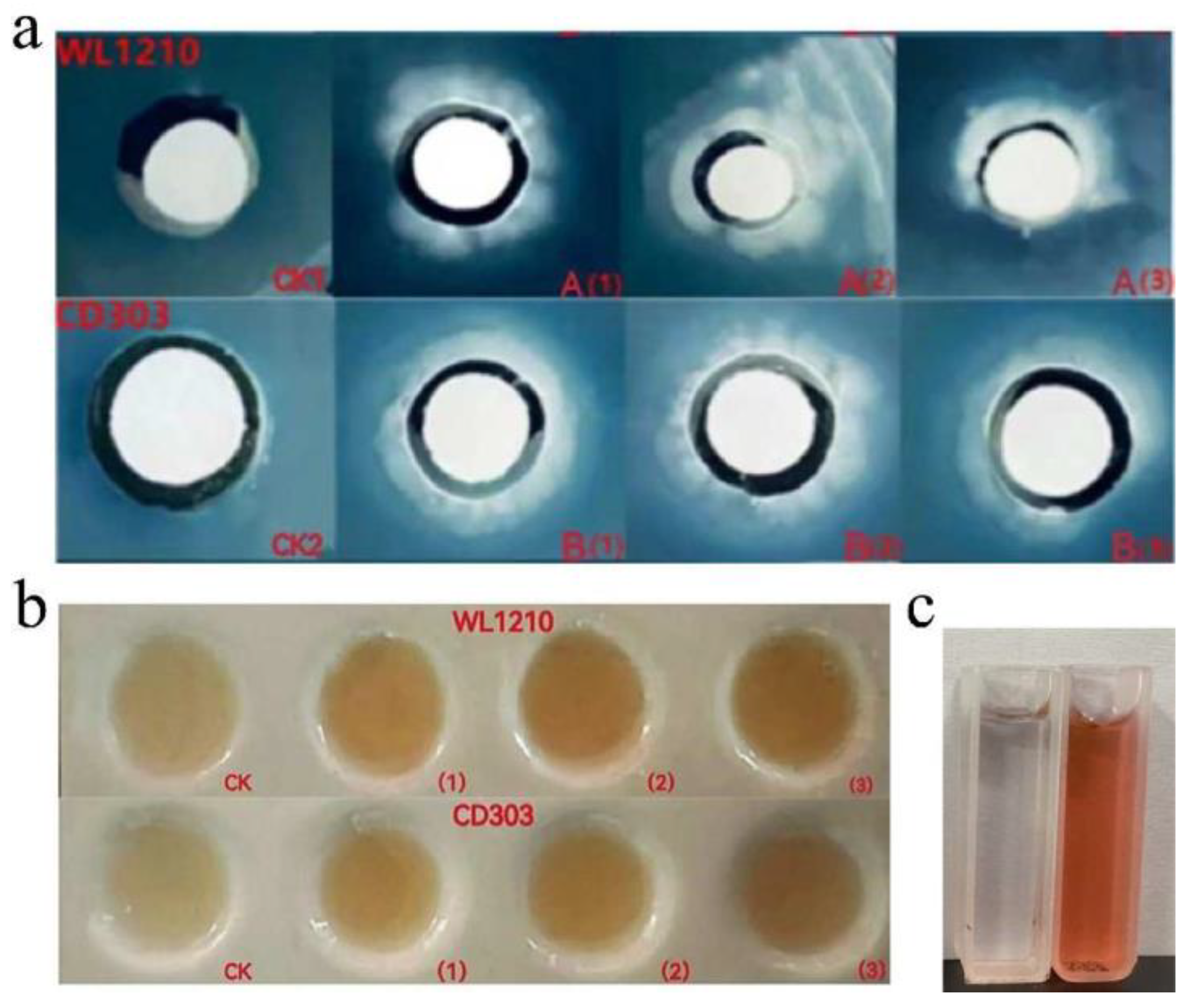

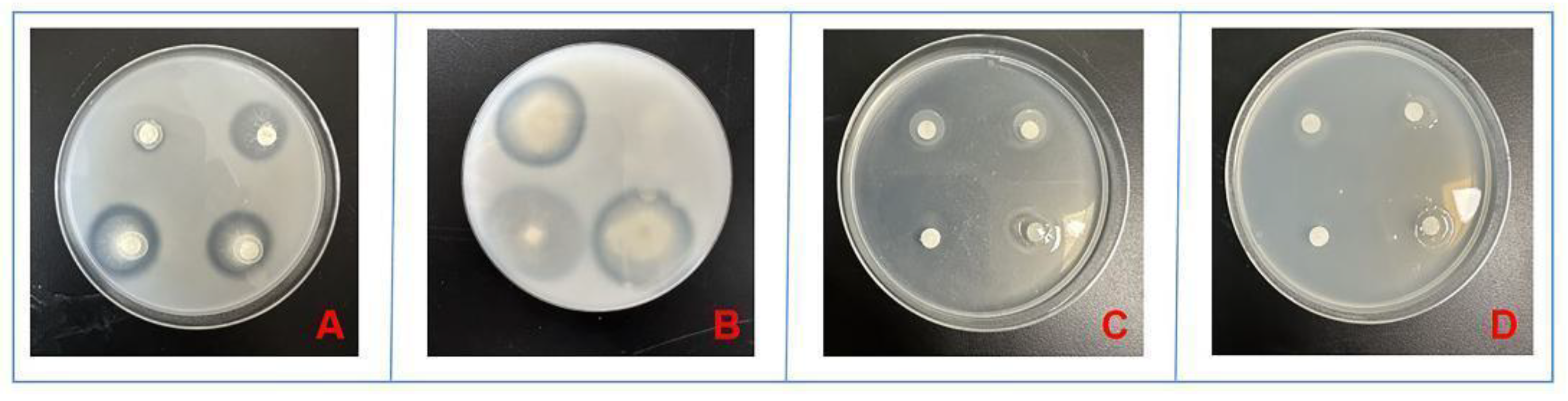

3.2.1 Siderophore-Producing Activities

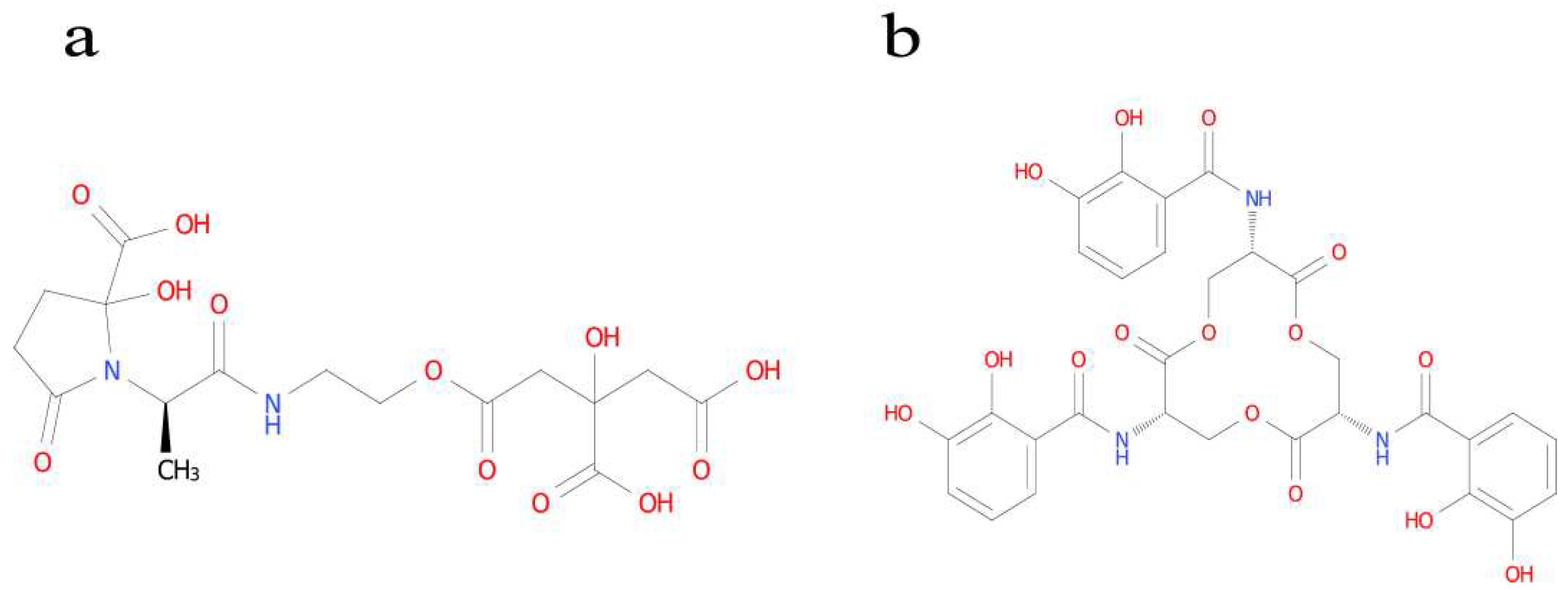

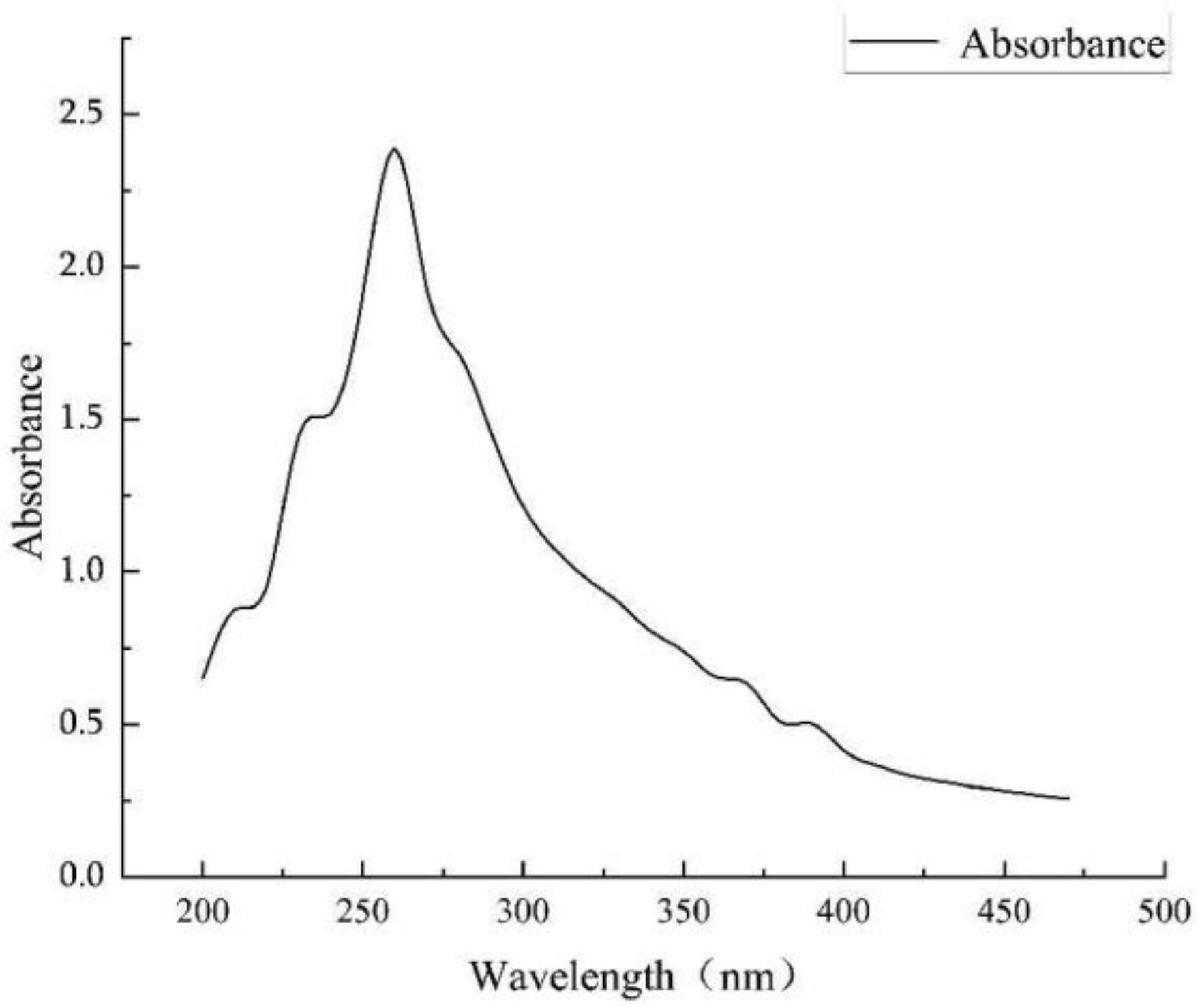

3.2.2. Identification of the Type of Ferrophilin Chelating Groups

3.3. Strains Ability to Produce CTK, GA and IAA

3.4. Phosphorus Solubilization and Potassium Release Activity Assay

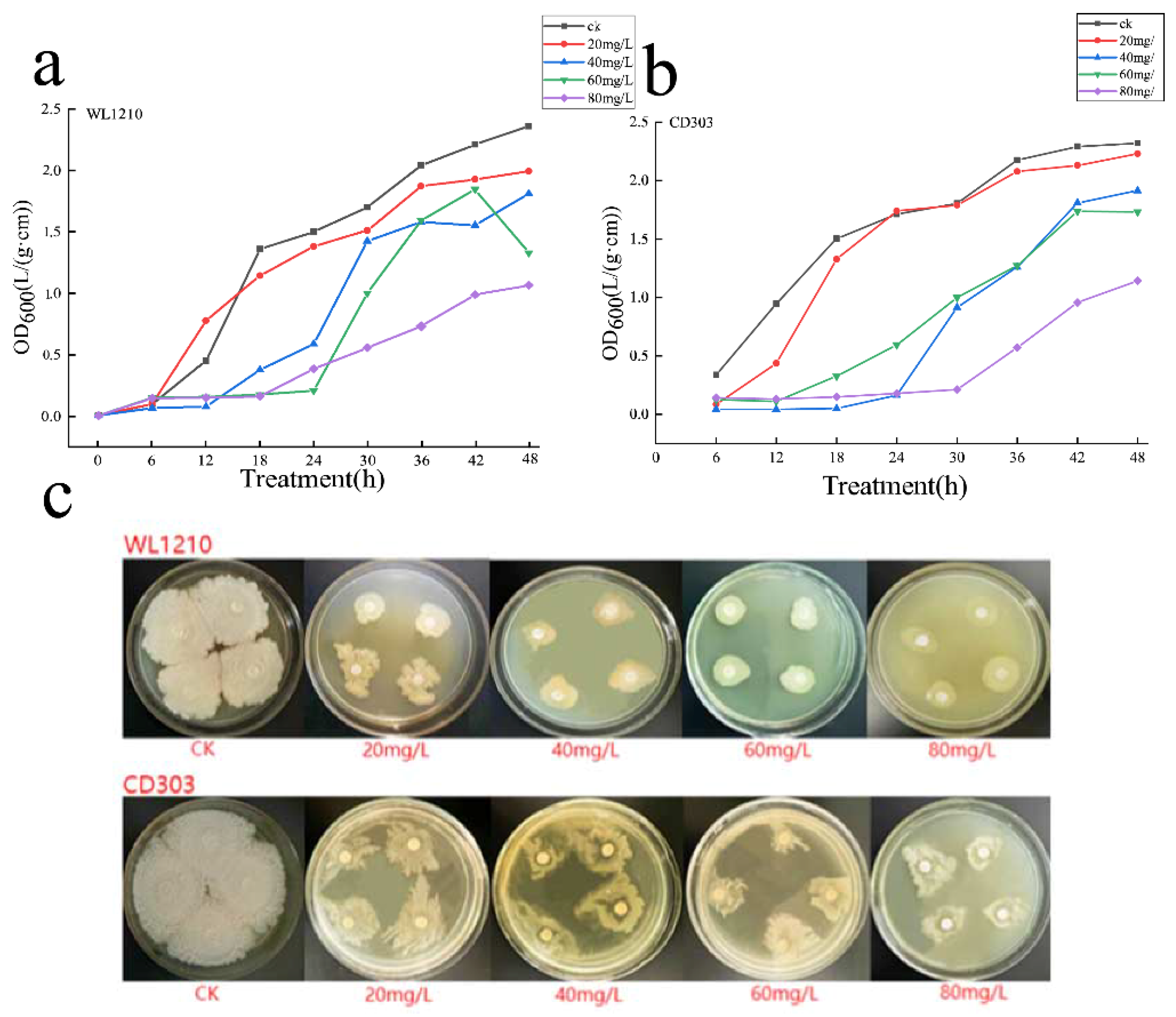

3.5. Cd2+ Tolerance of Strains

3.6 Effect of Strains on Ryegrass Growth Promotion under Cd2+ Stress

3.6.1. Effects of Cd2+ Stress on Ryegrass Seed Germination

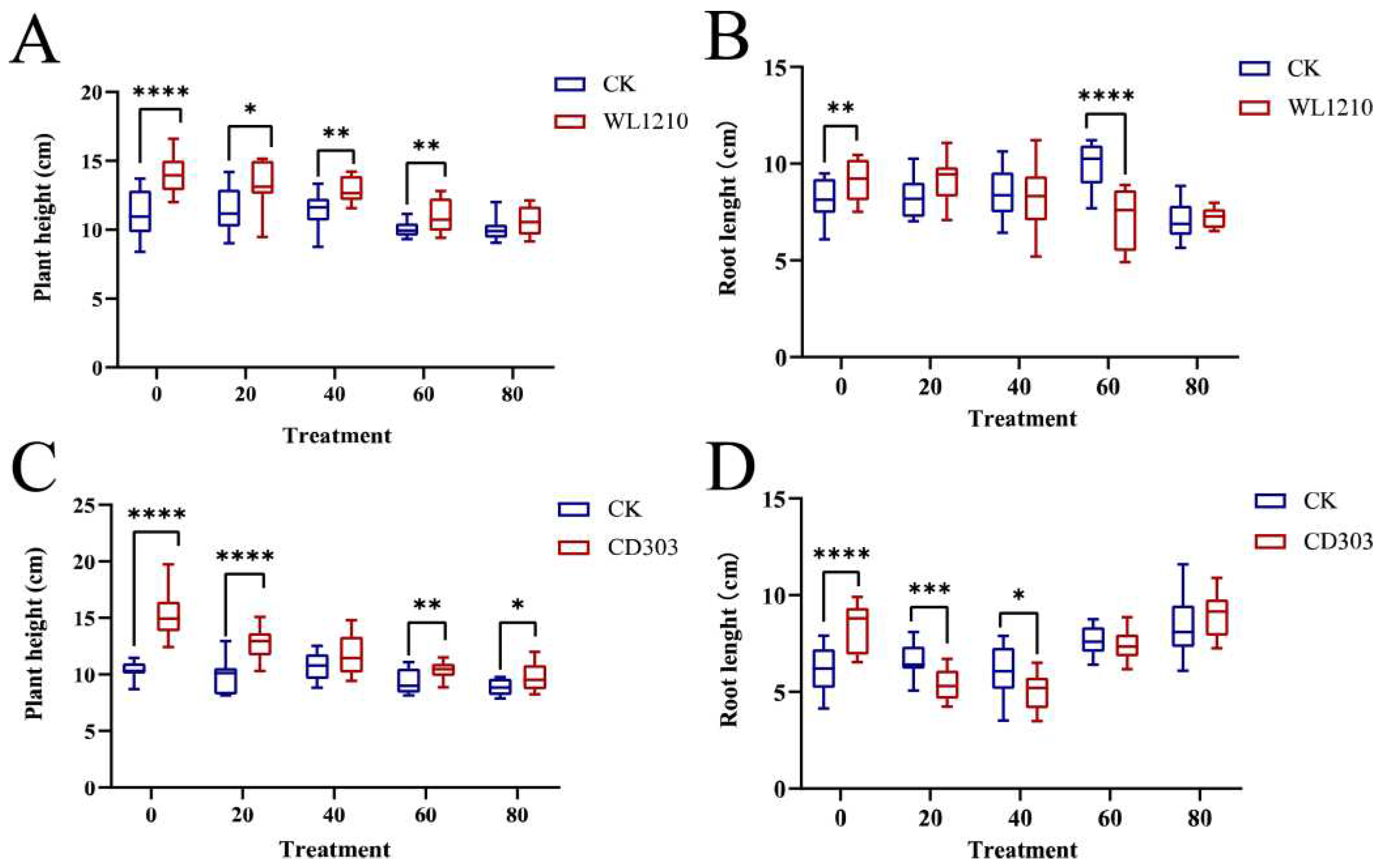

3.6.2. Effects of Strains on Ryegrass Biomass under Cd2+ Stress

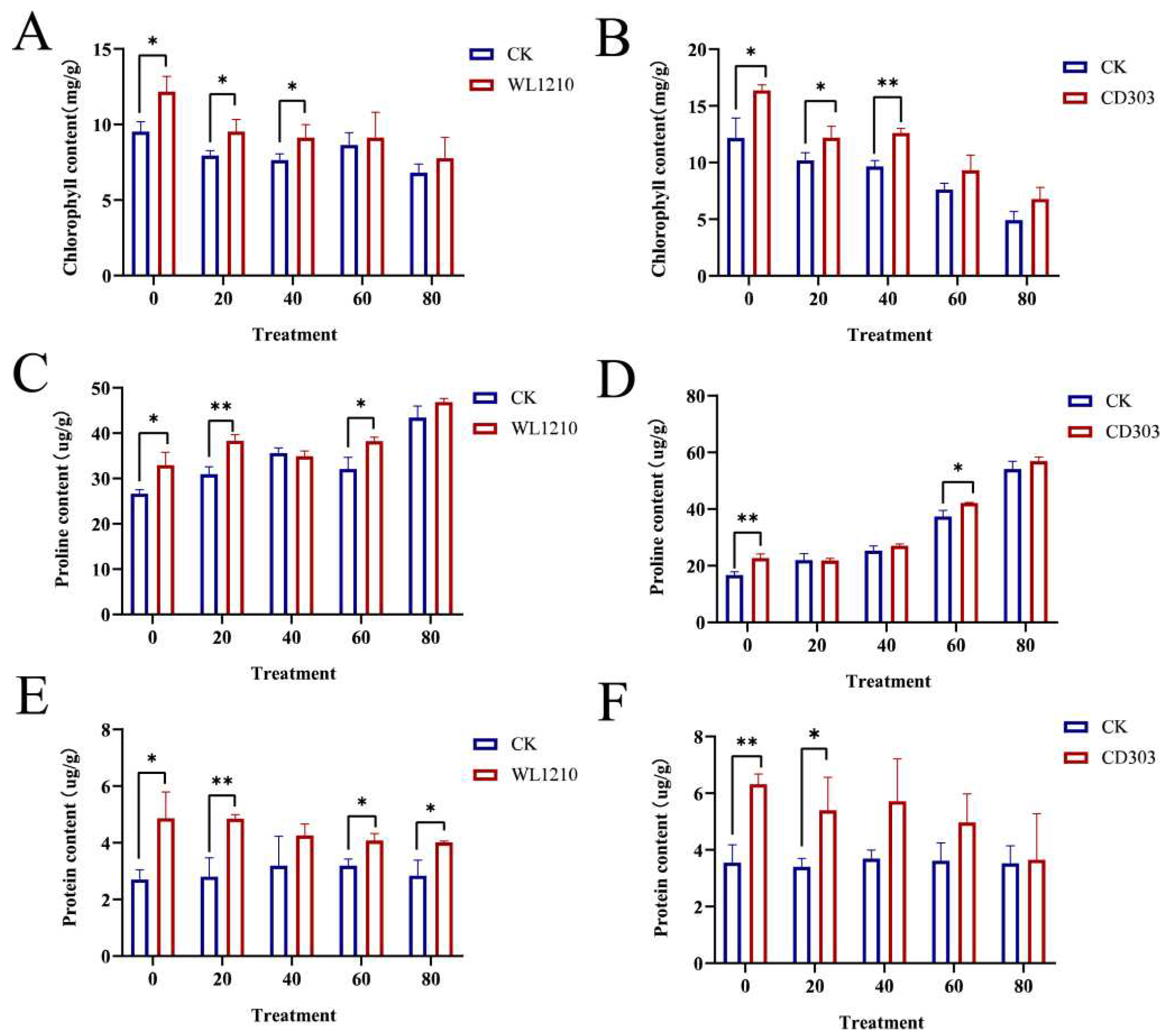

3.6.3. Effects of Strains on Chlorophyll Contents of Ryegrass under Cd2+ Stress

3.6.4. Effects of Strains on Proline Content of Ryegrass under Cd2+ Stress

3.6.5. Effect of Cd2+ and Strain Inoculation on Ryegrass Protein Concentrations

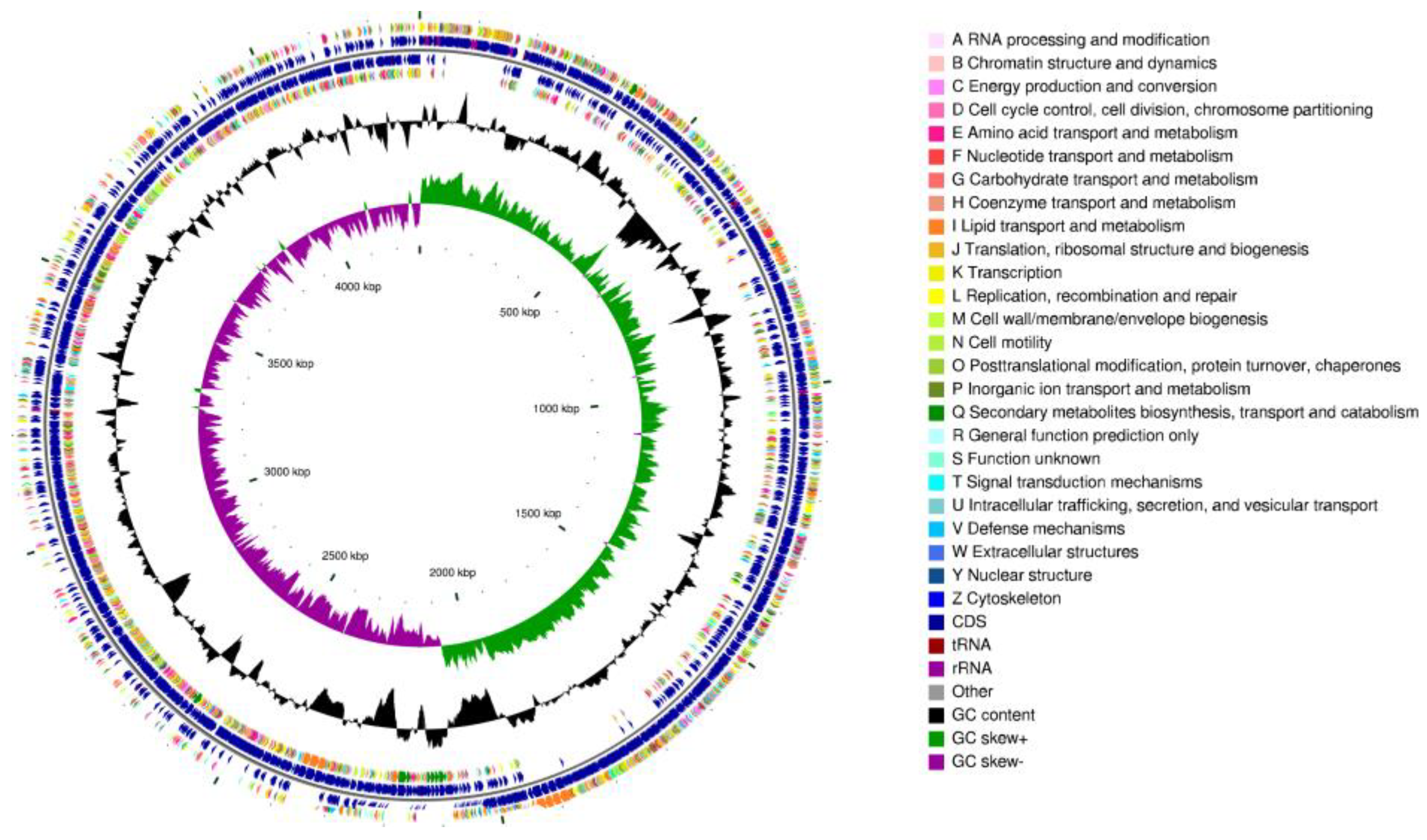

3.7. Genomic Characteristics of Strain CD303

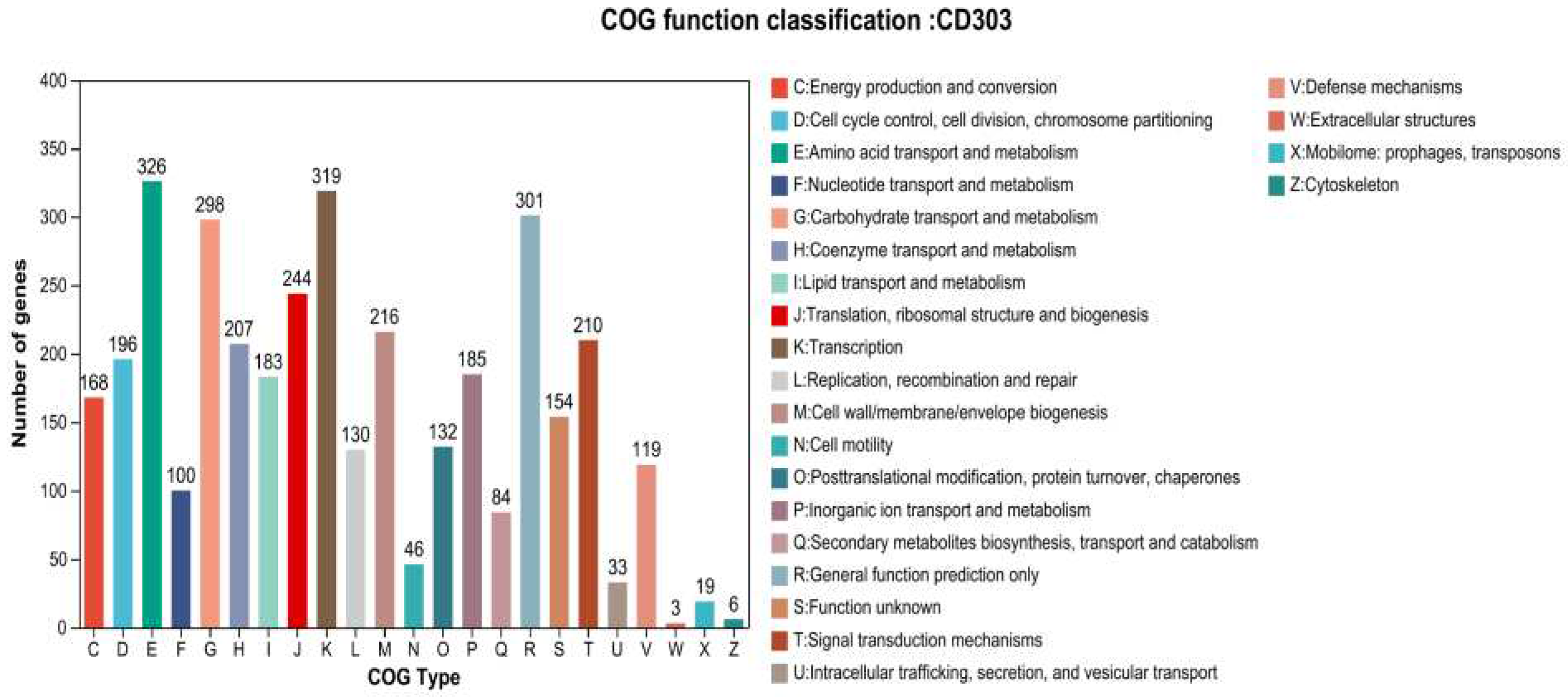

3.8. Functional Genes within the CD303 Genome

3.8.1. Growth-Promoting Functional Genes

3.8.2. Functional Annotation of the CD303 Gene

3.8.3. Stress Tolerance-Related Functional Genes

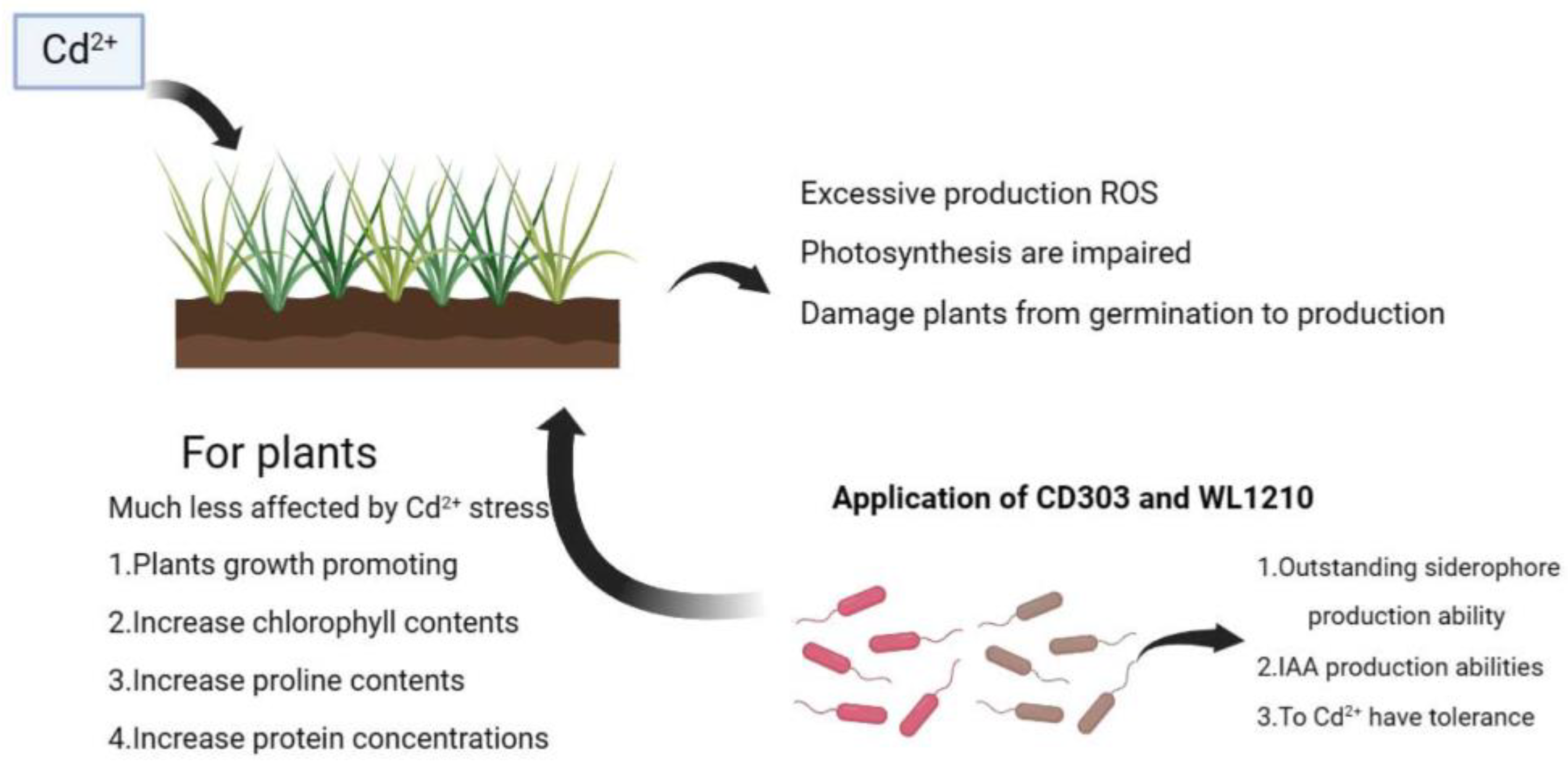

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zulfiqar, U.; Haider, F.U.; Maqsood, M.F.; et al. Recent Advances in Microbial-Assisted Remediation of Cadmium-Contaminated Soil. Plants 2023, 12, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, U.; Jiang, W.; Xiukang, W.; et al. Cadmium Phytotoxicity, Tolerance, and Advanced Remediation Approaches in Agricultural Soils; A Comprehensive Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 773815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adil, M.; Sehar, F.; et al. Cadmium-zinc cross-talk delineates toxicity tolerance in rice via differential genes expression and physiological/ultrastructural adjustments. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 190, 110076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Liu, L.L.; Cui, Z.G.; et al. Comparative study on protective effect of different selenium sources against cadmium-induced nephrotoxicity via regulating the transcriptions of selenoproteome. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 215, 112135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, U.; Ayub, A.; Hussain, S.; et al. Cadmium Toxicity in Plants: Recent Progress on Morpho-physiological Effects and Remediation Strategies. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 212–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, U.; Jiang, W.; Xiukang, W.; et al. Cadmium Phytotoxicity, Tolerance, and Advanced Remediation Approaches in Agricultural Soils; A Comprehensive Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 773815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yuan, R.; Sarkodie, E.K.; et al. Insight into functional microorganisms in wet-dry conversion to alleviate the toxicity of chromium fractions in red soil. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 977171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, D.S.; Jie, L.; Qibiao, L.; et al. Highly effective adsorption and passivation of Cd from wastewater and soil by MgO- and Fe3O4-loaded biochar nanocomposites. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Ilyas, N.; Yasmin, H.; et al. Role of Bacillus cereus in Improving the Growth and Phytoextractability of Brassica nigra (L.) K. Koch in Chromium Contaminated Soil. Molecules 2021, 26, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.S.; Wang, L.L.; Li, T.Q.; et al. Enhancing effect of siderophore-producting bacteria on remediation of cadmium-contaminated soil by Solanum nigrum L. J. Environ. Eng. 2018, 12, 2311–2319. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; He, L.; Zeng, Q.; Sheng, X. Surfactin production by Bacillus subtilis B12 under Cd stress and its effect on biofilm formation and Cd removal. Microbiol. China 2021, 48, 1883–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Xing, Y.; Huang, B.; et al. Rhizospheric mechanisms of Bacillus subtilis bioaugmentation-assisted phytostabilization of cadmium-contaminated soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 154136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Li, B.Z.; Wang, T.; et al. Study of Two Microbes Combined to Remediate Field Soil Cadmium Pollution. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 34, 364–369. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Guo, P.; Guo, S.; et al. Influence of electrical fields enhanced phytoremediation of multi-metal contaminated soil on soil parameters and plants uptake in different soil sections. Environ. Res. 2021, 198, 111290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, T.; Guo, G.; Liu, J.; et al. Improvement of the Cu and Cd phytostabilization efficiency of perennial ryegrass through the inoculation of three metal-resistant PGPR strains. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 271, 116314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- n WN. Plant Growth-promoting and Stress Tolerance Effect of Marine habitat Bacillus velezensis CT262. Zhejiang Agriculture and Forestry University, 2021.

- Liu, C.Z.; Jiang, X.L.; Cai, Q.Z.; Zhou, L.Y.; Yang, Q. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2021, 46, 5247–5252.

- Jiao, H.; Wang, R.; Qin, W.; Yang, J. Screening of rhizosphere nitrogen fixing, phosphorus and potassium solubilizing bacteria of Malus sieversii (Ldb.) Roem. and the effect on apple growth. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 292, 154142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xie, Y.L.; Wu, X.H.; et al. Molecular Identification and Bioactivity Analysis of Four Bacillus Strains Promoting the Growth of Alfalfa. Northwest J. Agric. 2023, 32, 212–221. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvepalli, M.; Velidandi, A.; Korrapati, N. Optimization of Siderophore Production in Three Marine Bacterial Isolates along with Their Heavy-Metal Chelation and Seed Germination Potential Determination. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballén, V.; Gabasa, Y.; Ratia, C.; Sánchez, M.; Soto, S. Correlation Between Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence Determinants and Biofilm Formation Ability Among Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli Strains Isolated in Catalonia, Spain. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 803862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xie, Y.L.; Wu, X.H.; et al. Avena sativa growth-promoting activity of Bacillus atrophaeus CKL1 under salt stress and the functional genes. Microbiol. Bull. 2022, 49, 3150–3164. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.L.; Yao, T.; Lan, X.J.; et al. Screening of Antagonistic Bacteria of Oat Root Rot and Studies of Antibacterial Properties. J. Grassl. Sci. 2022, 30, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Ma, Q.L.; Zhang, D.K.; et al. Effects of Exogenous Hormone on Seed Germination of Agriophyllum squarrosum. Chin. Agron. Bull. 2023, 39, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Amri, M.; Rjeibi, M.R.; Gatrouni, M.; et al. Isolation, Identification, and Characterization of Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria from Tunisian Soils. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, V.A.; Clément, E.; Arlt, J.; et al. A combined rheometry and imaging study of viscosity reduction in bacterial suspensions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 2326–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chieb, M.; Gachomo, E.W. The role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in plant drought stress responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, J.K.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil microbiomes and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atta, M.I.; Zehra, S.S.; Dai, D.Q.; et al. Amassing of heavy metals in soils, vegetables and crop plants irrigated with wastewater: Health risk assessment of heavy metals in Dera Ghazi Khan, Punjab, Pakistan. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1080635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.K.; Kumar, N.; Singh, N.P.; Santal, A.R. Phytoremediation technologies and their mechanism for removal of heavy metal from contaminated soil: An approach for a sustainable environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1076876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; O’Connor, D.; Igalavithana, A.D.; et al. Metal contamination and bioremediation of agricultural soils for food safety and sustainability. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, K.K.; Singh, C.K.; Kumar, M.; Singh, D.K. Whole-genome sequencing of Alcaligenes sp. strain MMA: insight into the antibiotic and heavy metal resistant genes. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1144561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D. Sustainable Remediation of Contaminated Soil and Groundwater: Materials, Processes, and Assessment (Butterworth-Heinemann. 2019.

- Waadt, R.; Seller, C.A.; Hsu, P.K.; Takahashi, Y.; Munemasa, S.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2022, 23, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, C.; Bei, S.; et al. High bacterial diversity and siderophore-producing bacteria collectively suppress Fusarium oxysporum in maize/faba bean intercropping. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 972587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, K.; Xue, Y.; Li, X.; Dong, C. Phylogeny of the HO family in cyprinus carpio and the response of the HO-1 gene to adding Bacillus coagulans in feed under Cd2+ stress. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 48, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, A.; Habib, M.; Kakavand, S.N.; et al. Phytoremediation of Cadmium: Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Mechanisms. Biology 2020, 9, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Singh, P.; Srivastava, A. Synthesis, nature and utility of universal iron chelator—Siderophore: A review. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 212–213, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, P.; Keutgen, A.J.; Keutgen, N.; et al. Photosynthetic efficiency of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) seedlings in response to Ni and Cd stress. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment Group | Description | Bacterial Suspension | Cd2+ Stress Treatment (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CK | Control | - | 0 |

| WL1210CD303 | WL1210 (CD303) Irrigation | + | 0 |

| 20 | 20 mg/L Cd2+ Stress + WL1210 (CD303) Irrigation | + | 20 |

| 40 | 40 mg/L Cd2+ Stress + WL1210 (CD303) Irrigation | + | 40 |

| 60 | 60 mg/L Cd2+ Stress + WL1210 (CD303) Irrigation | + | 60 |

| 80 | 80 mg/L Cd2+ Stress + WL1210 (CD303) Irrigation | + | 80 |

| Strain | Siderophore activity (%) | A/Ar |

|---|---|---|

| WL1210 | 36.16 | ++ |

| CD303 | 49.88 | +++ |

| Treatment concentration (mg/L) | Germination rate per day after bed placement (%) 7 d 8 d 9 d 10 d |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 78.00±4.00 | 81.3±5.77 | 85.33±9.45 | 91.33±6.11 |

| 20 | 76.00±5.29 | 78.6±8.08 | 84.0±12.00 | 88.00±12.41 |

| 40 | 78.00±3.46 | 83.3±6.42 | 84.00±9.16 | 88.67±9.45 |

| 60 | 77.33±6.11 | 81.3±5.77 | 83.00±8.71 | 83.33±9.45 |

| 80 | 18.00±4.00 | 18.6±3.06 | 29.33±11.37 | 34.67±11.79 |

| Concentration (mg/L) | GV (%) | GR (%) | GI | VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 78.00a | 91.33a | 4.99±0.44a | 15.92±3.04a |

| 20 | 76.0a | 88.00a | 4.85±0.44ab | 13.45±1.09ab |

| 40 | 78.00a | 88.67a | 4.99±0.50a | 10.89±1.06bc |

| 60 | 77.33a | 83.33a | 4.91±0.69a | 8.74±1.14c |

| 80 | 18.00b | 34.67b | 1.45±0.27b | 1.41±0.59d |

| Gene name | Location | Length | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| glpQ | 236068-236355 | 288 bp | Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase |

| hxlA | 380639-381271 | 633 bp | 3-hexulose-6-phosphate synthase |

| hxlB | 380075-380632 | 558 bp | Carbohydrate derivative metabolic process, isomerase activity, carbohydrate derivative binding |

| miaA | 1957705-1958649 | 945 bp | Isopentenyl adenine gene, considered the main cytokinin |

| miaB | 1861144-1862673 | 1530 bp | Isopentenyl adenine gene, considered the main cytokinin |

| ndhF | 197749-199266 | 1518 bp | NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5, Chloroplast functional genes |

| YBCL | 204425-205597 | 1173 bp | MFS transporter, encodes the Rubisco enzymes in plants, capable of converting carbon dioxide into organic matter |

| frmA | 372000-373136 | 1137 bp | Threonine dehydrogenase or related Zn-dependent dehydrogenase |

| phnB | 408798-409163 | 366 bp | Zn-dependent glyoxalase, PhnB family |

| fnr | 3382739-3383740 | 1002 bp | Ferredoxin--NADP reductase 2 |

| iscA | 3385318-3385680 | 363 bp | Iron-sulfur cluster assembly protein |

| ggt | 2146580-2148346 | 1767 bp | Plant stress tolerance enhancer |

| mgtC | 791225-791917 | 693 bp | Magnesium uptake protein YhiD/SapB, involved in acid resistance |

| proB | 2158357-2159481 | 1125 bp | Involved in proline or betaine synthesis, alleviates cell apoptosis |

| proC | 2159505-2160305 | 801 bp | Involved in proline or betaine synthesis, alleviates cell apoptosis |

| glnA | 1969335-1970669 | 1335 bp | Involved in the regulation of nitrogen fixation |

| glnR | 1968870-1969277 | 408 bp | Involved in the regulation of nitrogen fixation |

| licA | 382536-393302 | 10767 bp | Surfactin non-ribosomal peptide synthetase SrfAA |

| licB | 393324-404093 | 10770 bp | Surfactin non-ribosomal peptide synthetase SrfAB |

| licC | 404112-407942 | 3831 bp | Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase |

| srfATE | 407970-408704 | 735 bp | Surfactin biosynthesis thioesterase SrfAD |

| acpT | 411550-412224 | 675 bp | 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferase superfamily protein |

| tcyC | 413260-414003 | 744 bp | Amino acid ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

| bsdA | 415642-416514 | 873 bp | LysR family transcriptional regulator |

| oxa | 231253-232089 | 837 bp | Penicillin-binding protein transpeptidase domain |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).