Submitted:

27 January 2024

Posted:

30 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Previous Studies and Gaps Identification

2.2. The Study’s Theoretical Framework

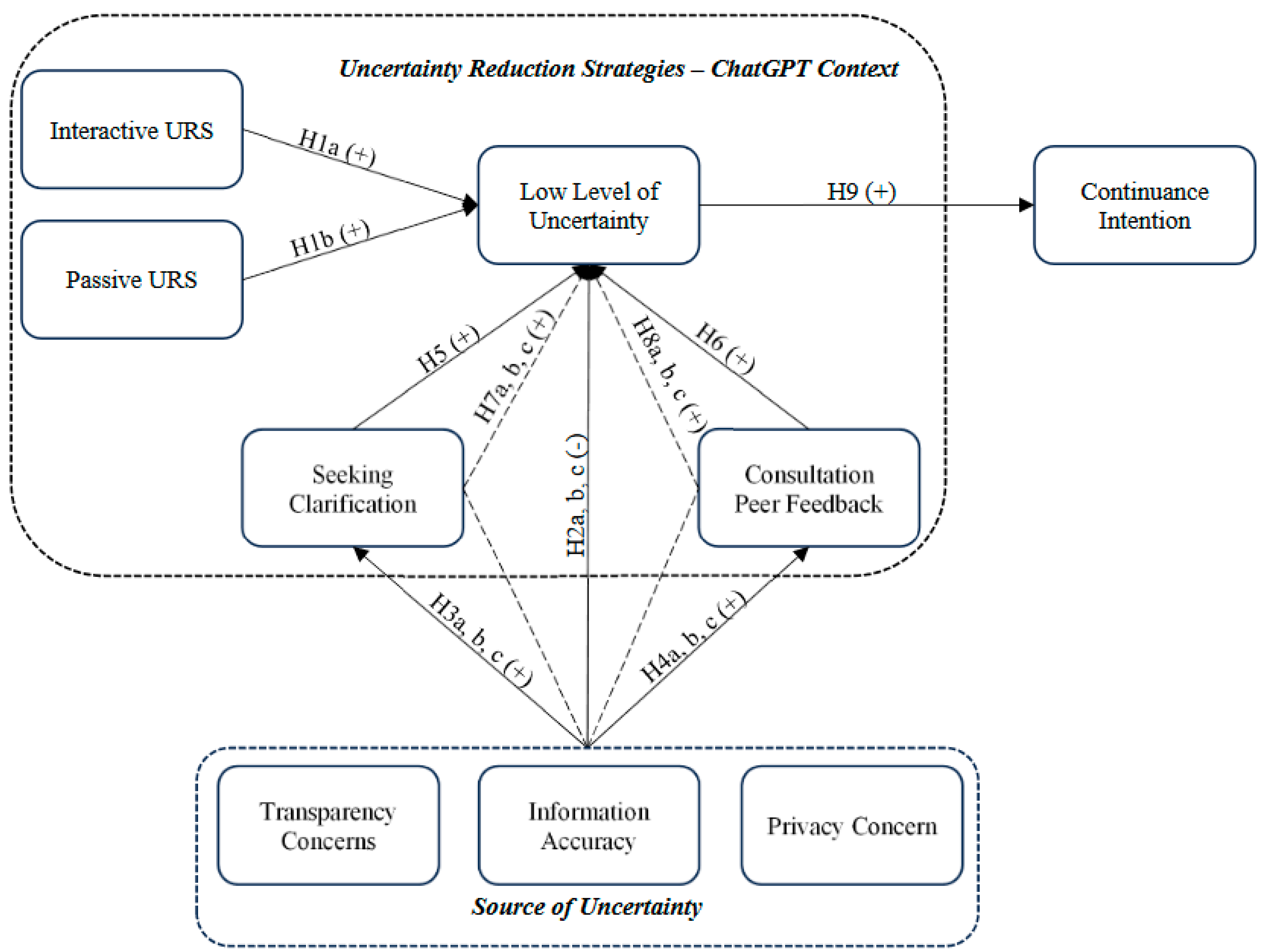

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. URS to Reduce Uncertainty

3.2. Source of Uncertainty and Low-Level Uncertainty

3.3. Source of Uncertainty, Seeking for Clarification and Consultation Peer Feedback

3.4. Seeking Clarification to Reduce Uncertainty

3.5. Consultation Peer Feedback to Reduce Uncertainty

3.6. Mediating Effect of Seeking Clarification

3.7. Mediating Effect of Consultation Peer Feedback

3.8. Reduced Uncertainty to Continuance Intention

4. Methods

4.1. Operationalization and Measures

4.2. Sampling Technique and Data Collection

4.3. Analysis Technique

5. Results

5.1. Sample Demographics

5.2. Common Method Variance

5.3. Assessment of Validity and Reliability

| CPF | CI | IA | INT | LLU | PSS | PC | SC | TC | |

| CPF | 0.883 | ||||||||

| CI | 0.200 (0.268) |

0.847 | |||||||

| IA | 0.319 (0.499) |

0.220 (0.351) |

0.838 | ||||||

| INT | 0.302 (0.454) |

0.309 (0.465) |

0.315 (0.455) |

0.884 | |||||

| LLU | 0.414 (0.629) |

0.306 (0.453) |

0.254 (0.374) |

0.457 (0.644) |

0.867 | ||||

| PSS | 0.311 (0.557) |

0.290 (0.534) |

0.256 (0.463) |

0.345 (0.421) |

0.207 (0.257) |

0.857 | |||

| PC | 0.389 (0.603) |

0.313 (0.466) |

0.434 (0.654) |

0.221 (0.315) |

0.303 (0.442) |

0.346 (0.624) |

0.871 | ||

| SC | 0.161 (0.239) |

0.456 (0.748) |

0.358 (0.558) |

0.418 (0.595) |

0.176 (0.240) |

0.379 (0.661) |

0.354 (0.521) |

0.774 | |

| TC | 0.358 (0.555) |

0.391 (0.616) |

0.419 (0.613) |

0.504 (0.729) |

0.429 (0.629) |

0.334 (0.560) |

0.401 (0.558_ |

0.454 (0.678) |

0.866 |

Notes:

| |||||||||

5.4. Model Robustness Test

5.5. Hypothesis Testing

5.5.1. Direct Hypothesis

5.5.2. Mediating Hypothesis

6. Discussion

7. Implication

7.1. Theoretical Implication

7.2. Practical Implication

8. Limitation and Avenues for Future Research

References

- Thormundsson, Bergur. (2023). Growth forecast of monthly active users of ChatGPT in December 2022 and January 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1368657/chatgpt-mau-growth/#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20around%2057%20million,100%20million%20by%20January%202023. Accessed at 2nd October 2023.

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., ... & Wright, R. (2023). “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102642. [CrossRef]

- Baek, T. H., & Kim, M. (2023). Is ChatGPT scary good? How user motivations affect creepiness and trust in generative artificial intelligence. Telematics and Informatics, 83, 102030. [CrossRef]

- Bin-Nashwan, S. A., Sadallah, M., & Bouteraa, M. (2023). Use of ChatGPT in academia: Academic integrity hangs in the balance. Technology in Society, 102370. [CrossRef]

- Mijwil, M., & Aljanabi, M. (2023). Towards artificial intelligence-based cybersecurity: the practices and ChatGPT generated ways to combat cybercrime. Iraqi Journal For Computer Science and Mathematics, 4(1), 65-70. [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, M., Ghazi, M., Ali, A. H., & Abed, S. A. (2023). ChatGPT: open possibilities. Iraqi Journal For Computer Science and Mathematics, 4(1), 62-64. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S. (2022). Open artificial intelligence platforms in nursing education: Tools for academic progress or abuse?. Nurse Education in Practice, 66, 103537-103537. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, C. K., Bhat, M. A., Khan, S. T., Subramaniam, R., & Khan, M. A. I. (2023). What drives students toward ChatGPT? An investigation of the factors influencing adoption and usage of ChatGPT. Interactive Technology and Smart Education. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., & Huo, Y. (2023). Are users willing to embrace ChatGPT? Exploring the factors on the acceptance of chatbots from the perspective of AIDUA framework. Technology in Society, 102362. [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A. (2023). To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Interactive Learning Environments, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Pradana, M., Elisa, H. P., & Syarifuddin, S. (2023). Discussing ChatGPT in education: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2243134. [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B., Senali, M. G., Iranmanesh, M., Khanfar, A., Ghobakhloo, M., Annamalai, N., & Naghmeh-Abbaspour, B. (2023). Determinants of Intention to Use ChatGPT for Educational Purposes: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D. R., Cotton, P. A., & Shipway, J. R. (2023). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. (2023, March). ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. In Healthcare (Vol. 11, No. 6, p. 887). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, M. (2023). ChatGPT: Future directions and open possibilities. Mesopotamian journal of Cybersecurity, 2023, 16-17. [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., Ueno, A., & Dennis, C. (2023). ChatGPT and consumers: Benefits, pitfalls and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(4), 1213-1225. [CrossRef]

- Teel, Z. A., Wang, T., & Lund, B. (2023). ChatGPT conundrums: Probing plagiarism and parroting problems in higher education practices. College & Research Libraries News, 84(6), 205. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S. S., Xu, M., Patros, P., Wu, H., Kaur, R., Kaur, K., ... & Buyya, R. (2024). Transformative effects of ChatGPT on modern education: Emerging Era of AI Chatbots. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems, 4, 19-23. [CrossRef]

- Farrokhnia, M., Banihashem, S. K., Noroozi, O., & Wals, A. (2023). A SWOT analysis of ChatGPT: Implications for educational practice and research. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G., & Ma, C. (2023). Measuring EFL learners’ use of ChatGPT in informal digital learning of English based on the technology acceptance model. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L. M., Hurd, E., & Brinegar, K. M. (2023). Critical race theory, books, and ChatGPT: Moving from a ban culture in education to a culture of restoration. Middle School Journal, 54(3), 2-4. [CrossRef]

- Nune, A., Iyengar, K., Manzo, C., Barman, B., & Botchu, R. (2023). Chat generative pre-trained transformer (ChatGPT): potential implications for rheumatology practice. Rheumatology International, 43(7), 1379-1380. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S. I., Lee, K. Y., & Yang, S. B. (2017). How do uncertainty reduction strategies influence social networking site fan page visiting? Examining the role of uncertainty reduction strategies, loyalty and satisfaction in continuous visiting behavior. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5), 449-462. [CrossRef]

- Hong, X., Pan, L., Gong, Y., & Chen, Q. (2023). Robo-advisors and investment intention: A perspective of value-based adoption. Information & Management, 60(6), 103832. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., & Choi, J. (2017). Enhancing user experience with conversational agent for movie recommendation: Effects of self-disclosure and reciprocity. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 103, 95-105. [CrossRef]

- Berger, C. R., & Calabrese, R. J. (1974). Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human communication research, 1(2), 99-112. [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M., Mohsin, Z., & Khaliq, S. (2021, July). User Satisfaction with an AI-Enabled Customer Relationship Management Chatbot. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 279-287). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Delgosha, M. S., & Hajiheydari, N. (2021). How human users engage with consumer robots? A dual model of psychological ownership and trust to explain post-adoption behaviours. Computers in Human Behavior, 117, 106660. [CrossRef]

- Sturman, N., Tan, Z., & Turner, J. (2017). “A steep learning curve”: junior doctor perspectives on the transition from medical student to the health-care workplace. BMC medical education, 17(1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Spooren, P., Brockx, B., & Mortelmans, D. (2013). On the validity of student evaluation of teaching: The state of the art. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 598-642. [CrossRef]

- Antheunis, M. L., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2010). Getting acquainted through social network sites: Testing a model of online uncertainty reduction and social attraction. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(1), 100-109. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S., Cui, J., & Mou, Y. (2023). Desirable or Distasteful? Exploring Uncertainty in Human-Chatbot Relationships. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Whalen, E. A., & Belarmino, A. (2023). Risk mitigation through source credibility in online travel communities. Anatolia, 34(3), 414-425. [CrossRef]

- Gudykunst, W. B., Chua, E., & Gray, A. J. (1987). Cultural dissimilarities and uncertainty reduction processes. Annals of the International Communication Association, 10(1), 456-469. [CrossRef]

- Emmers, T. M., & Canary, D. J. (1996). The effect of uncertainty reducing strategies on young couples' relational repair and intimacy. Communication Quarterly, 44(2), 166-182. [CrossRef]

- Brashers, D. E. (2001). Communication and uncertainty management. Journal of communication, 51(3), 477-497. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., Chan, F. K., & Hu, P. J. (2016). Managing citizens’ uncertainty in e-government services: The mediating and moderating roles of transparency and trust. Information systems research, 27(1), 87-111. [CrossRef]

- Kokolakis, S. (2017). Privacy attitudes and privacy behaviour: A review of current research on the privacy paradox phenomenon. Computers & security, 64, 122-134. [CrossRef]

- Tidwell, L. C., & Walther, J. B. (2002). Computer-mediated communication effects on disclosure, impressions, and interpersonal evaluations: Getting to know one another a bit at a time. Human communication research, 28(3), 317-348. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A. J., & Irwin, J. (2014). “Defining what we do—all over again”: Occupational identity, technological change, and the librarian/Internet-search relationship. Academy of Management Journal, 57(3), 892-928. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M. (1996). Observing the observer: Self-regulation in the observational learning of motor skills. Developmental review, 16(2), 203-240. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Prentice Hall: Englewood cliffs.

- Firat, M. (2023). What ChatGPT means for universities: Perceptions of scholars and students. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- Menichetti, J., Hillen, M. A., Papageorgiou, A., & Pieterse, A. H. (2023). How can ChatGPT be used to support healthcare communication research?. Patient Education and Counseling, 115, 107947. [CrossRef]

- Aghemo, A., Forner, A., & Valenti, L. (2023). Should Artificial Intelligence-based language models be allowed in developing scientific manuscripts? A debate between ChatGPT and the editors of Liver International. Liver International, 43(5), 956-957. [CrossRef]

- Ayinde, L., Wibowo, M. P., Ravuri, B., & Emdad, F. B. (2023). ChatGPT as an important tool in organizational management: A review of the literature. Business Information Review, 02663821231187991. [CrossRef]

- Morocco-Clarke, A., Sodangi, F. A., & Momodu, F. (2023). The implications and effects of ChatGPT on academic scholarship and authorship: a death knell for original academic publications?. Information & Communications Technology Law, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Alawida, M., Mejri, S., Mehmood, A., Chikhaoui, B., & Isaac Abiodun, O. (2023). A Comprehensive Study of ChatGPT: Advancements, Limitations, and Ethical Considerations in Natural Language Processing and Cybersecurity. Information, 14(8), 462. [CrossRef]

- Jo, H. (2023). Decoding the ChatGPT mystery: A comprehensive exploration of factors driving AI language model adoption. Information Development, 02666669231202764. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, K. K. (2012). Multiple conversations during organizational meetings: Development of the multicommunicating scale. Management Communication Quarterly, 26(2), 195-223. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, E. A., & Shin, E. K. (2010). Peer feedback: Who, what, when, why, & how. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 46(3), 112-117.

- Ashford, S. J., Blatt, R., & VandeWalle, D. (2003). Reflections on the looking glass: A review of research on feedback-seeking behavior in organizations. Journal of management, 29(6), 773-799. [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P. A., Liang, H., & Xue, Y. (2007). Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: A principal-agent perspective. MIS quarterly, 105-136. [CrossRef]

- Filip, G., Meng, X., Burnett, G., & Harvey, C. (2017, May). Human factors considerations for cooperative positioning using positioning, navigational and sensor feedback to calibrate trust in CAVs. In 2017 Forum on Cooperative Positioning and Service (CPGPS) (pp. 134-139). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y. J., So, H. J., & Kim, N. H. (2018). Examination of relationships among students' self-determination, technology acceptance, satisfaction, and continuance intention to use K-MOOCs. Computers & Education, 122, 260-272. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H. S., & Ko, K. S. (2020). Sustainable development of Fintech: Focused on uncertainty and perceived quality issues. Sustainability, 12(18), 7669. [CrossRef]

- Adarkwah, M. A., Ying, C., Mustafa, M. Y., & Huang, R. (2023, August). Prediction of Learner Information-Seeking Behavior and Classroom Engagement in the Advent of ChatGPT. In International Conference on Smart Learning Environments (pp. 117-126). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS quarterly, 351-370. [CrossRef]

- Aysolmaz, B., Müller, R., & Meacham, D. (2023). The public perceptions of algorithmic decision-making systems: Results from a large-scale survey. Telematics and Informatics, 79, 101954. [CrossRef]

- Li, E. Y. (1997). Perceived importance of information system success factors: A meta analysis of group differences. Information & management, 32(1), 15-28. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., Michael, K., & Chen, X. (2013). Factors affecting privacy disclosure on social network sites: an integrated model. Electronic Commerce Research, 13, 151-168. [CrossRef]

- Pitardi, V., & Marriott, H. R. (2021). Alexa, she's not human but… Unveiling the drivers of consumers' trust in voice-based artificial intelligence. Psychology & Marketing, 38(4), 626-642. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial management & data systems, 117(3), 442-458. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 43, 115-135. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press.

- Baumgartner, H., Weijters, B., & Pieters, R. (2021). The biasing effect of common method variance: Some clarifications. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49, 221-235. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M. A., Burn, J. M., Gemoets, L. A., & Jacquez, C. (2000). Variables affecting information technology end-user satisfaction: a meta-analysis of the empirical literature. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 52(4), 751-771. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Pavo, M. Á. (2021). Collaborative learning for virtual higher education. Learning, culture and social interaction, 28, 100437. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M., Akiri, C., Aryal, K., Parker, E., & Praharaj, L. (2023). From ChatGPT to ThreatGPT: Impact of generative AI in cybersecurity and privacy. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Artificial Intelligence Context? | Focus on Reducing Uncertainty? | Mediating Effect of Seeking Clarification and Consultation Peer Feedback? | Objectives | Theory | Main Findings |

| Pan et al. (2023) [32] | Yes | No | No | This study systematically examines user concerns and uncertainties in their interactions with AI-driven social chatbots, with a focus on a Chinese online community, providing a cross-cultural perspective. | Non-URT (Using Sentiment Analysis) | Users experience four key uncertainties: technical, relational, ontological, and sexual. These encompass concerns about chatbot functionality, the nature of the relationship, chatbot identity, and boundaries in intimate interactions. Visibility and sentiment analysis reveal the dynamic and context-dependent nature of user responses to these uncertainties, contributing to a broader understanding of human-AI interactions. |

| Shin et al. (2017) [23] | No (SNS focus reducing uncertainty from various perceptions) |

No (Only focus on investigation of low level of uncertainty from interactive and passive USR) |

No | This study investigates into Facebook fan page dynamics and their followers' recurring visits, examining how URS, perceived content usefulness, SNS satisfaction, and SNS loyalty influence this behavior. | URT | The study conclusively establishes that URS decrease uncertainty about fan page information, enhancing perceived posting usefulness and promoting continuous visits. Moreover, SNS satisfaction and loyalty effectively moderate these relationships. |

| Hong et al. (2023) [24] | No (Focus on Financial Robot-Advisor) |

No (Reducing the risk using URS of financial robot-advisor) |

No | The study aims to fill a gap in existing empirical research by examining how URS influence users' investment intentions when utilizing financial robo-advisors. | URT & VBAM | This study links algorithm transparency, assurance, and interactivity strategies to higher user investment intentions in financial robo-advisors, offering guidance for service providers. |

| Lee & Choi (2017) [25] | No | No | No | This study examines how communication variables and the conversational agent-user relationship affect user satisfaction and intention to use an interactive movie recommendation system. It analyzes the influence of self-disclosure and reciprocity on user satisfaction. | URT & CASA | The findings emphasize that trust and interactional enjoyment mediate communication variables' impact on user satisfaction. Reciprocity outweighs self-disclosure in agent-user relationship building. Notably, user satisfaction significantly influences usage intention. |

| This study | Yes (Focus on investigation of AI-powered ChatGPT) |

Yes (Offering the mediating effect and different strategies of URS to achieve low-level uncertainty) |

Yes (Integrating seeking clarification and consultation peer feedback into URT) |

There are several objectives:

|

URT | The findings of this research suggest that interactive URS represent the most significant strategy for attaining low levels of uncertainty. On the other hand, it appears that the source of uncertainty is notably mediated, primarily through consultation of peer feedback, which proves to be a more effective approach compared to seeking clarification (an individual stage). Ultimately, this study also establishes that when users achieve low levels of uncertainty in their interactions with ChatGPT, this significantly translates into continued behavioral intention. Hence, this research effectively integrates the source of uncertainty (e.g., transparency concern, information accuracy, and privacy concern) into the Uncertainty Reduction Theory (URT) model. On the other hand, the integration of consultation of peer feedback as a mediating factor appears to be a favorable approach in engaging users towards the ethical utilization of ChatGPT for academic purposes. |

| Constructs | Definition | Measurement Items | OL | CA | CR | AVE | |

| Interactive URS | Antheunis et al. (2010) [31] | Modified from Antheunis et al. (2010) [31] | |||||

| Interactive strategies involve direct engagement between the user and the AI model. One such interactive strategy is the use of direct questions, while another involves sharing self-disclosure information. | Commented or given feedback on ChatGPT’s responses. (*) | 0.670 | 0.719 | 0.877 | 0.781 | ||

| Asked for more information or clarification from ChatGPT | 0.889 | ||||||

| Shared your thoughts on comments made by others regarding ChatGPT’s responses | 0.878 | ||||||

| Passive URS | Antheunis et al. (2010) [31] | Modified from Antheunis et al. (2010) [31] | |||||

| Passive strategies are those in which an informant unobtrusively observes the target person, for example in situations in which the target person reacts to or interacts with others. | Observed ChatGPT’s responses without actively participating in the conversation | 0.973 | 0.769 | 0.795 | 0.736 | ||

| Reviewed ChatGPT’s responses and observed its interactions without active involvement | 0.726 | ||||||

| Read comments or feedback from other users on ChatGPT’s responses. (*) | 0.678 | ||||||

| Low level of Uncertainty | This study | Modified from Shin et al. (2017) [23] | |||||

| Low-level uncertainty suggests a high degree of user trust and belief in the AI's proficiency, resulting in a more positive and confident user experience when using ChatGPT for various purposes | I have confidence that ChatGPT's responses reduce uncertainty. (*) | 0.619 | 0.897 | 0.869 | 0.751 | ||

| I feel uncertainty about ChatGPT's responses is low. | 0.866 | ||||||

| There is low uncertainty when I rely on ChatGPT’s responses for information or decision-making. | 0.867 | ||||||

| Seeking for Clarification | This study | Modified from Stephens (2012) [50] | |||||

| Seeking clarification pertains to actively seeking information and clarification directly from ChatGPT (individual – system level of clarification). | Actively sought clarification from ChatGPT to ensure you understood its responses. | 0.725 | 0.762 | 0.817 | 0.599 | ||

| Requested clarification from ChatGPT to make its responses clearer and more understandable. | 0.843 | ||||||

| Asked questions to ChatGPT to reduce uncertainty and enhance your understanding of the conversation. | 0.747 | ||||||

| Consultation Peer Feedback | This study | Modified from Stephens (2012) [50] | |||||

| A dynamic and co-creative process that transcends the traditional concept of users merely providing insights to one another, signifies a complex collaboration between users (e.g., students, educators) and AI-powered models (e.g., ChatGPT). | Shared ChatGPT’s responses with friends or colleagues and asked for their opinions. (*) | 0.676 | 0.811 | 0.836 | 0.718 | ||

| Sought advice or feedback from peers about the information provided by ChatGPT. | 0.818 | ||||||

| Compared ChatGPT’s responses with information or opinions from friends or colleagues. | 0.875 | ||||||

| Continuance Intention | Bhattacherjee (2001) [58] | Modified from Baek & Kim (2023) [3] | |||||

| Continuance intention is the user's intent to persist in utilizing the technology. | I plan to keep using ChatGPT | 0.903 | 0.708 | 0.831 | 0.711 | ||

| I want to continue using ChatGPT | 0.780 | ||||||

| Transparency Concern | Modified from Aysolmaz et al. (2023) [59] | Modified from Aysolmaz et al. (2023) [59] | |||||

| Transparency concerns for a system, when perceived by users, result in the system being viewed as having lower levels of fairness, privacy, and accountability. Consequently, this leads to lower levels of trust and perceived usefulness of the system. | I’m concerned when it’s unclear how ChatGPT produces information. | 0.875 | 0.766 | 0.857 | 0.749 | ||

| It bothers me if ChatGPT doesn’t explain how it gets information or offers suggestions. | 0.856 | ||||||

| Information Accuracy | Li (1997) [60] | Adapted from Foroughi et al. (2023) [12] | |||||

| Information accuracy pertains to the degree to which the provided information is accurate enough to fulfill its intended purpose. | Information from ChatGPT is correct. (*) | 0.432 | 0.793 | 0.824 | 0.702 | ||

| Information from ChatGPT is reliable. | 0.758 | ||||||

| Information from ChatGPT is accurate. | 0.911 | ||||||

| Privacy Concern | Xu et al. (2013) [61] | Modified from Pitardi et al. (2021) [62] | |||||

| Privacy concern relates to users' apprehensions regarding potential threats to their online privacy. | I doubt the privacy of my interactions with ChatGPT. (*) | 0.692 | 0.781 | 0.862 | 0.757 | ||

| I worry that my personal data on ChatGPT could be stolen. | 0.869 | ||||||

| I'm concerned that ChatGPT collects too much information about me. | 0.872 | ||||||

Notes:

| |||||||

| Measures | Category | Frequency | % |

| Gender | Male | 257 | 45.4 |

| Female | 309 | 54.6 | |

| Age (years old) | < 20 | 47 | 8.3 |

| 21 – 30 | 183 | 32.3 | |

| 31 – 40 | 181 | 32 | |

| 41 – 50 | 104 | 18.4 | |

| > 50 | 51 | 9 | |

| Educational Level | Vocational Studies | 44 | 7.8 |

| Undergraduate | 197 | 34.8 | |

| Master | 262 | 46.3 | |

| Doctorate | 63 | 11.1 | |

| Status | Students | 66 | 11.7 |

| Lecturers | 376 | 66.4 | |

| Researchers | 124 | 21.9 | |

| Type of University | Public University | 160 | 28.4 |

| Private University | 400 | 70.6 | |

| Foreign University | 6 | 1 | |

| Type of ChatGPT | GPT 3.5 | 307 | 54.2 |

| GPT 4.0 | 259 | 45.8 | |

| Usage Frequency | Never | 0 | 0 |

| Once a month | 32 | 5.6 | |

| Several times a month | 65 | 11.5 | |

| Once a week | 17 | 3 | |

| Several times a week | 147 | 25.9 | |

| Once a day | 121 | 21.4 | |

| Several times a day | 184 | 32.6 | |

| How long have you used ChatGPT? | Less than one month | 78 | 13.8 |

| One month | 191 | 33.7 | |

| Less than six months | 272 | 48.1 | |

| Less than one year | 25 | 4.4 |

| Constructs | Items | Loadings and Cross-Loading Matrix | ||||||||

| CPF | CI | IA | INT | LLU | PSS | PC | SC | TC | ||

| Continuance Intention | CI.1 | 0.276 | 0.903 | 0.204 | 0.276 | 0.299 | 0.283 | 0.324 | 0.367 | 0.338 |

| CI.2 | 0.017 | 0.780 | 0.164 | 0.246 | 0.205 | 0.195 | 0.184 | 0.442 | 0.326 | |

| Consultation Peer Feedback | CPF.2 | 0.818 | 0.021 | 0.227 | 0.232 | 0.319 | 0.263 | 0.322 | 0.099 | 0.260 |

| CPF.3 | 0.875 | 0.295 | 0.308 | 0.278 | 0.379 | 0.264 | 0.337 | 0.169 | 0.342 | |

| Information Accuracy | IA.2 | 0.182 | 0.135 | 0.758 | 0.170 | 0.143 | 0.168 | 0.262 | 0.253 | 0.203 |

| IA.3 | 0.329 | 0.221 | 0.911 | 0.331 | 0.262 | 0.250 | 0.438 | 0.337 | 0.455 | |

| Interactive URS | INT.2 | 0.258 | 0.286 | 0.287 | 0.889 | 0.413 | 0.177 | 0.203 | 0.398 | 0.484 |

| INT.3 | 0.277 | 0.260 | 0.270 | 0.878 | 0.394 | 0.439 | 0.187 | 0.339 | 0.404 | |

| Low Level of Uncertainty | LOW.2 | 0.329 | 0.204 | 0.224 | 0.389 | 0.866 | 0.111 | 0.291 | 0.095 | 0.395 |

| LOW.3 | 0.394 | 0.328 | 0.221 | 0.411 | 0.867 | 0.248 | 0.243 | 0.210 | 0.358 | |

| Privacy Concern | PC.2 | 0.371 | 0.225 | 0.395 | 0.182 | 0.266 | 0.328 | 0.869 | 0.266 | 0.268 |

| PC.3 | 0.306 | 0.320 | 0.362 | 0.202 | 0.262 | 0.275 | 0.872 | 0.351 | 0.429 | |

| Passive URS | PSS.1 | 0.271 | 0.244 | 0.218 | 0.372 | 0.221 | 0.973 | 0.286 | 0.326 | 0.298 |

| PSS.2 | 0.300 | 0.312 | 0.267 | 0.093 | 0.065 | 0.726 | 0.388 | 0.383 | 0.300 | |

| Seeking for Clarification | SCL.1 | 0.248 | 0.354 | 0.268 | 0.372 | 0.264 | 0.323 | 0.283 | 0.725 | 0.324 |

| SCL.2 | 0.078 | 0.366 | 0.304 | 0.276 | 0.019 | 0.299 | 0.247 | 0.843 | 0.324 | |

| SCL.3 | 0.033 | 0.354 | 0.256 | 0.305 | 0.101 | 0.251 | 0.282 | 0.747 | 0.395 | |

| Transparency Concern | TC.1 | 0.342 | 0.344 | 0.514 | 0.390 | 0.382 | 0.264 | 0.470 | 0.388 | 0.875 |

| TC.2 | 0.276 | 0.332 | 0.203 | 0.485 | 0.360 | 0.315 | 0.216 | 0.398 | 0.856 | |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficient | T-Value | Bootstrapping 97.5% | Conclusion | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| H1a, INT URS ➔ LLU | 0.321*** | 6.550 | 0.222 | 0.415 | Supported |

| H1b, PSS URS ➔ LLU | -0.039 | 0.852 | -0.125 | 0.059 | Unsupported |

| H2a, TC ➔ LLU | -0.024 | 0.856 | -0.101 | 0.096 | Unsupported |

| H2b, IA ➔ LLU | -0.008 | 0.164 | -0.100 | 0.085 | Unsupported |

| H2c, PC ➔ LLU | 0.018 | 1.301 | 0.015 | 0.217 | Unsupported |

| H3a, TC ➔ SC | 0.327*** | 7.056 | 0.231 | 0.413 | Supported |

| H3b, IA ➔ SC | 0.152** | 3.175 | 0.057 | 0.246 | Supported |

| H3c, PC ➔ SC | 0.157** | 3.169 | 0.059 | 0.250 | Supported |

| H4a, TC ➔ CPF | 0.205*** | 4.560 | 0.119 | 0.293 | Supported |

| H4b, IA ➔ CPF | 0.123** | 2.444 | 0.024 | 0.222 | Supported |

| H4c, PC ➔ CPF | 0.253*** | 4.973 | 0.154 | 0.352 | Supported |

| H5, SC ➔ LLU | -0.112 | 1.848 | -0.229 | 0.007 | Unsupported |

| H6, CPF ➔ LLU | 0.231*** | 4.854 | 0.134 | 0.320 | Supported |

| H9, LLU ➔ CI | 0.306*** | 6.603 | 0.219 | 0.398 | Supported |

Notes:

| |||||

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficient | T-Value | Bootstrapping 97.5% | Conclusion | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| H7a, TC ➔ SC ➔ LLU | -0.036 | 1.735 | -0.080 | 0.002 | Non-mediation |

| H7b, IA ➔ SC ➔ LLU | -0.017 | 1.482 | -0.044 | 0.001 | Non-mediation |

| H7c, PC ➔ SC ➔ LLU | -0.017 | 1.513 | -0.043 | 0.001 | Non-mediation |

| H8a, TC ➔ CPF ➔ LLU | 0.047*** | 3.295 | 0.022 | 0.078 | Full mediation |

| H8b, IA ➔ CPF ➔ LLU | 0.028** | 2.172 | 0.005 | 0.056 | Full mediation |

| H8c, PC ➔ CPF ➔ LLU | 0.058*** | 3.552 | 0.029 | 0.093 | Full mediation |

Notes:

| |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).