1. Introduction

Information geometry (IG) is a state-of-the-art geometric methodology that looks at both model analysis and geometry visualisation from an IG standpoint. The wide spectrum of IG applicability includes much-needed new disciplines, such as machine learning [

1]. Even more intriguingly, statistical manifolds (SMs) were studied using IG.

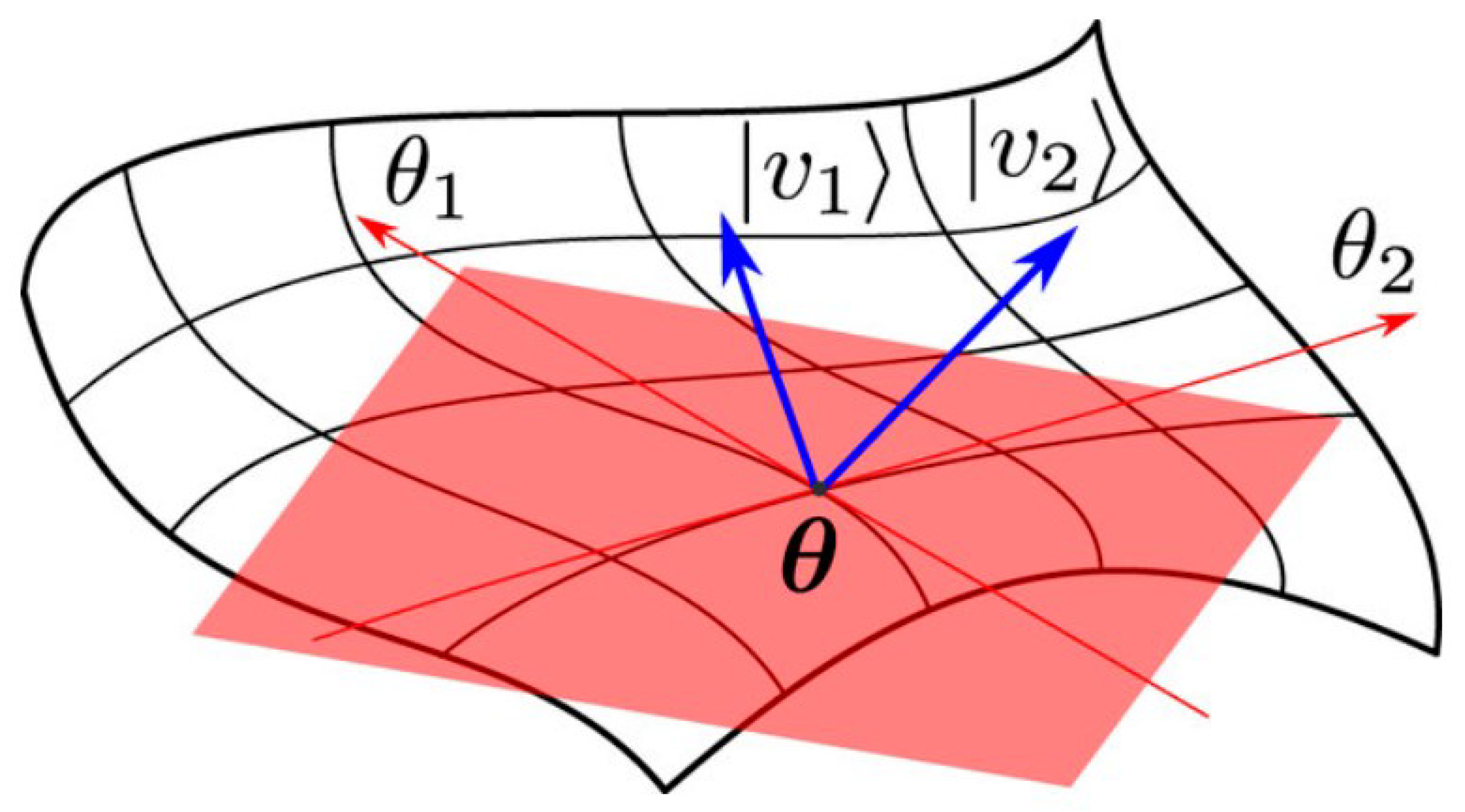

Figure 1 illustrates a statistical manifold

(

) [

2],

In this context, IG is a geometric methodology used to analyze models and visualize geometry. It involves studying statistical manifolds, which are defined by probability measurements. The Fisher information metric (FIM) is a key concept in IG, representing a smooth statistical manifold that quantifies the informative difference between measurements [

3,

4].

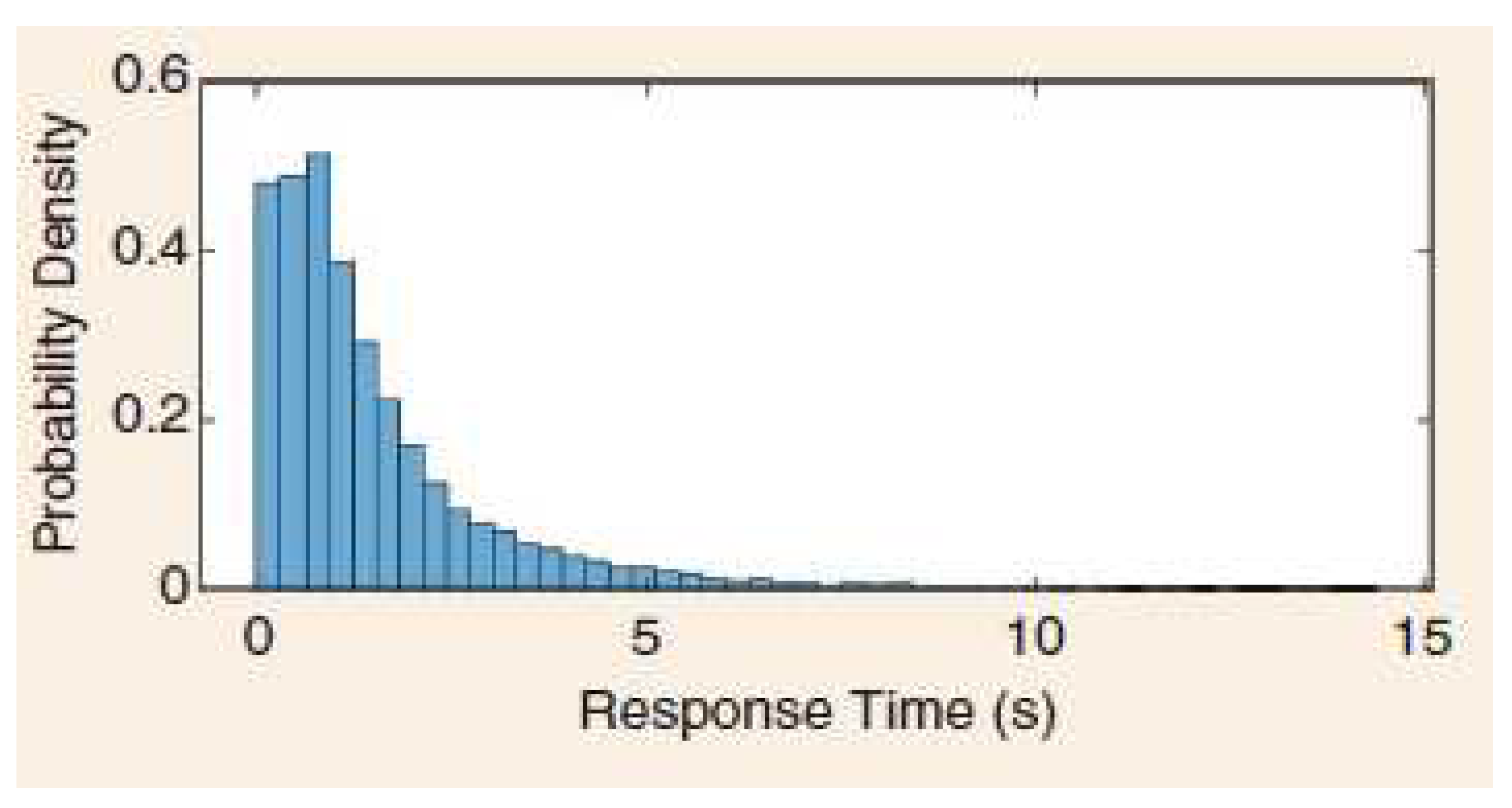

The current exposition establishes the first- time ever revolutionary IG analysis of Human Trust-Based Feedback Control (HTBFC). The real motivation behind this current innovative study is based on the provided probabilistic distribution of human response time [

5]. This drives our creative line of investigation into the reimagining of IG-connected Human-Machine Interactions (HMIs).

The remainder of this paper is as follows: IG’s first definitions are provided in Section II. Section III provides a summary of the HTBFC’s historical background. The primary results are presented in Section IV by calculating FIM, its inverse, and the FIM of the HTBFC. Section V highlights the important contribution that HTBFC has made to the advancement of robotics. In conclusion, Section VI includes next phase research as well as a few difficult unsolved challenging open problems.

2. Main IG Definitions

Definition 1 [6]

is a statistical manifold if is a random variable in sample space and a pdf under some requirements, with coordinates.

-

is given by

is a manifold.

Definition 2 [6].

define the n-free component of containing

Definition 3 [7]. FIM, namely [

]) reads as

Definition 4 [8]. Having FIM, we define its [

] by

4. The Information Geometrics of the HTBFC Manifold

Theorem 1 HTBFC Manifold of (4) and (6), satisfies:

- (ii)

takes the form

where

is the determinant of

, C is the matrix of cofactors of

, and

represents the matrix transpose.

Proof We have

Thus, it follows that:

Following (6), we can re-write

Such that

Therefore,

To this end, we obtain

reads as:

We have

Hence, FIM (c.f., (i)) follows.

(ii) follows by the definition of Inverse matrices.

Now, we are going to provide examples for both two- and three-dimensional cases.

The two-dimensional case

Due to the higher complexity of the mathematical calculations of [] (c.f., (19)), it is more favorable to explore the two-dimensional special case.

Let

This reduces the generated potential function,

(c.f., (23)) to take the form:

This implies:

Consequently,

Thus, the determinant of

],

will be given by

So,

if and only if

Which is impossible, since both

are pre-defined to be positive. This demonstrates that [

] exists.

Following some mathematical steps, it can be verified that:

The three-dimensional case

Moving to the three-dimensional configuration, for example, putting

(c.f., (23)), it follows that:

In analogy to the above proofs, it can be easily shown that the three-dimensional generated HTBFC manifold is characterized by

This triggers a new breakthrough:

What are the values of the three-dimensional vector to guarantee the existence of the inverse FIM matrix, []?

To answer this triggering question, set

Consequently, it is implied that:

Hence,

or

By (45),

, we have

Therefore, [

] will exist if and only if

Thus, [

] will take the form:

with c.f., (42) and (47)).

Based on the above analysis, [] always exists in the two-dimensional case, whereas its existence is constrained by are positive real numbers. It is expected that the four-dimensional case will impose more restrictions to the existence of [].

5. HTBFC Applications to Robotics

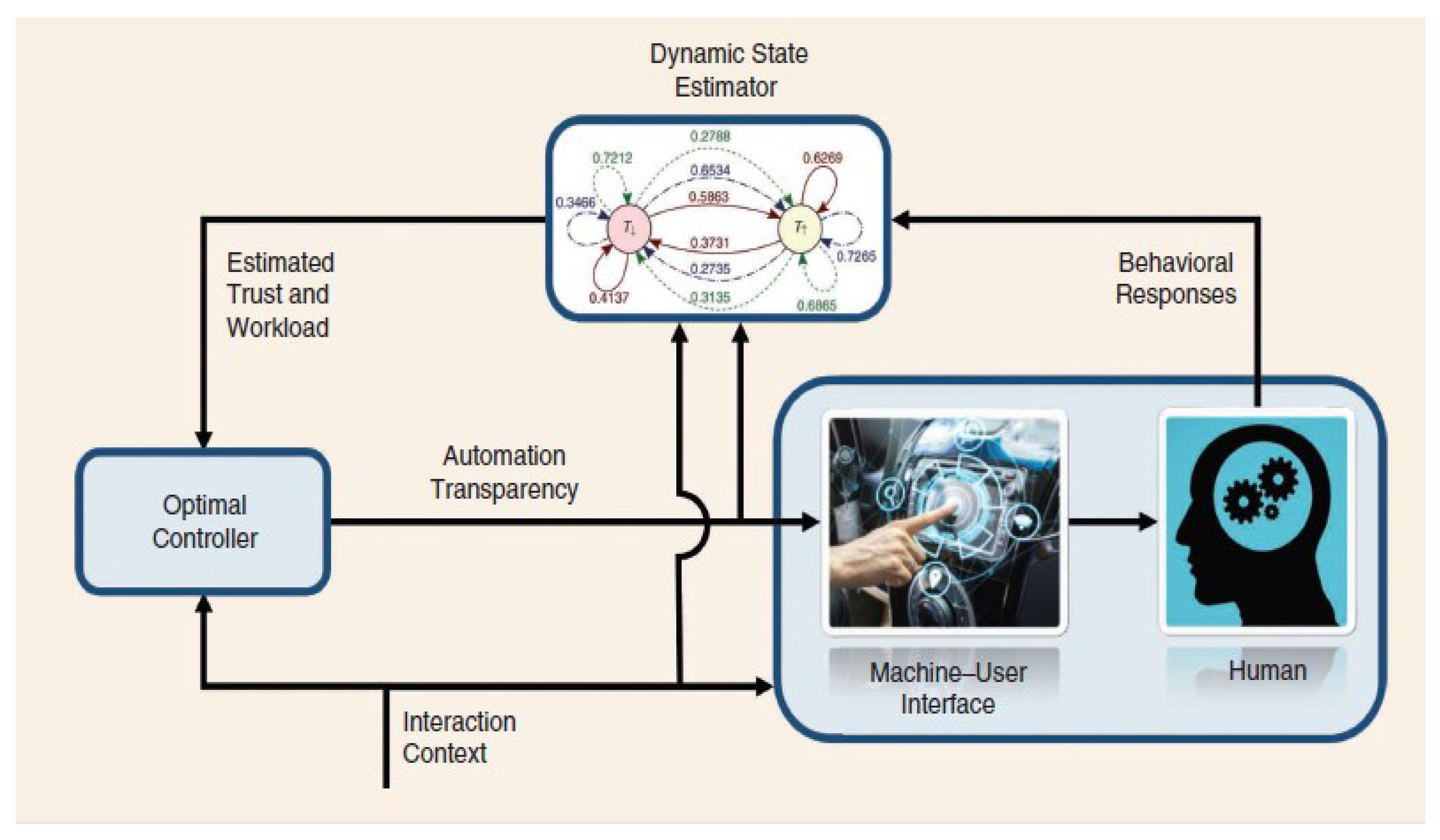

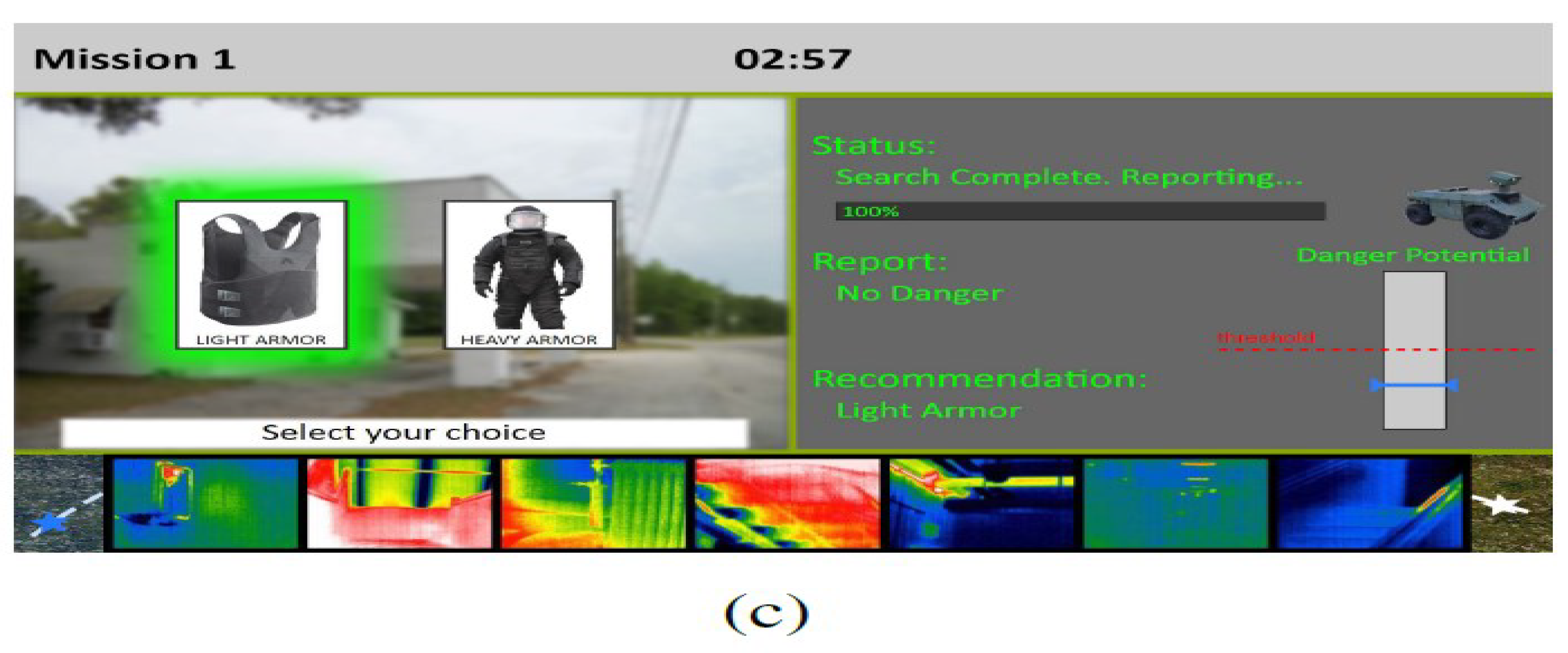

Researchers ran an experiment where participants engaged with a simulation comprising numerous reconnaissance missions to better understand HTBFC [

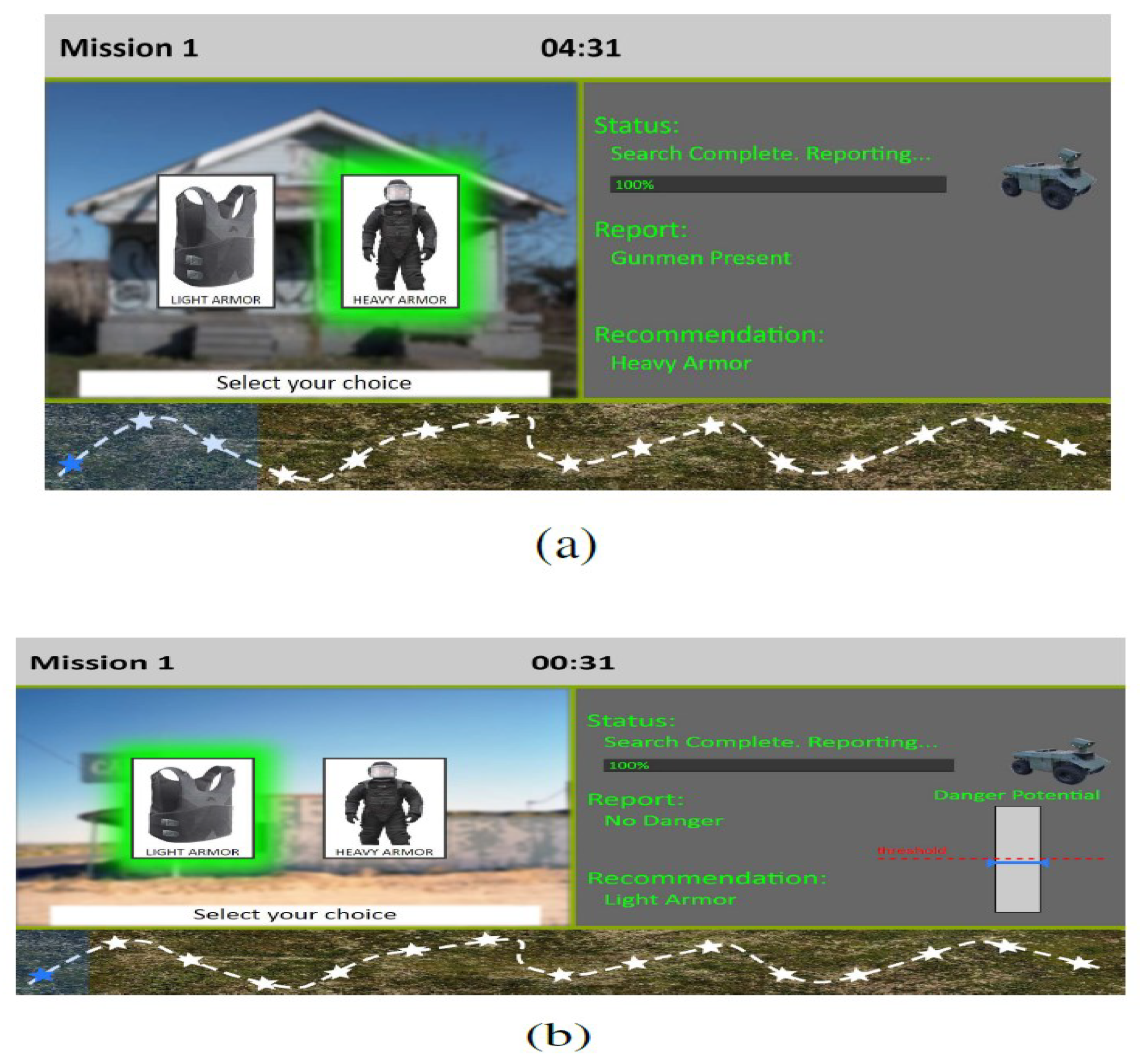

16] and workload in a decision-aid system. Participants had to search buildings to assess their level of safety or danger based on the presence of armed men. To maximize both speed and safety, a decision-assistance robot made suggestions regarding whether to wear light or heavy armor during the hunt. The study examined the effects of various system transparency levels on user workload, performance, and human-robot interaction trust.

Participants were helped by a robot that varied in transparency during each mission of the experiment [

16]. The low transparency robot suggested Armor and disclosed whether there were any armed assailants. The medium transparency robot added a sensor bar that indicated the perceived level of danger, and the high transparency robot added thermal photos taken inside the building. As

Figure 4 [

16] illustrates, it’s crucial to remember that various degrees of transparency might change according to automation, context, and viability.

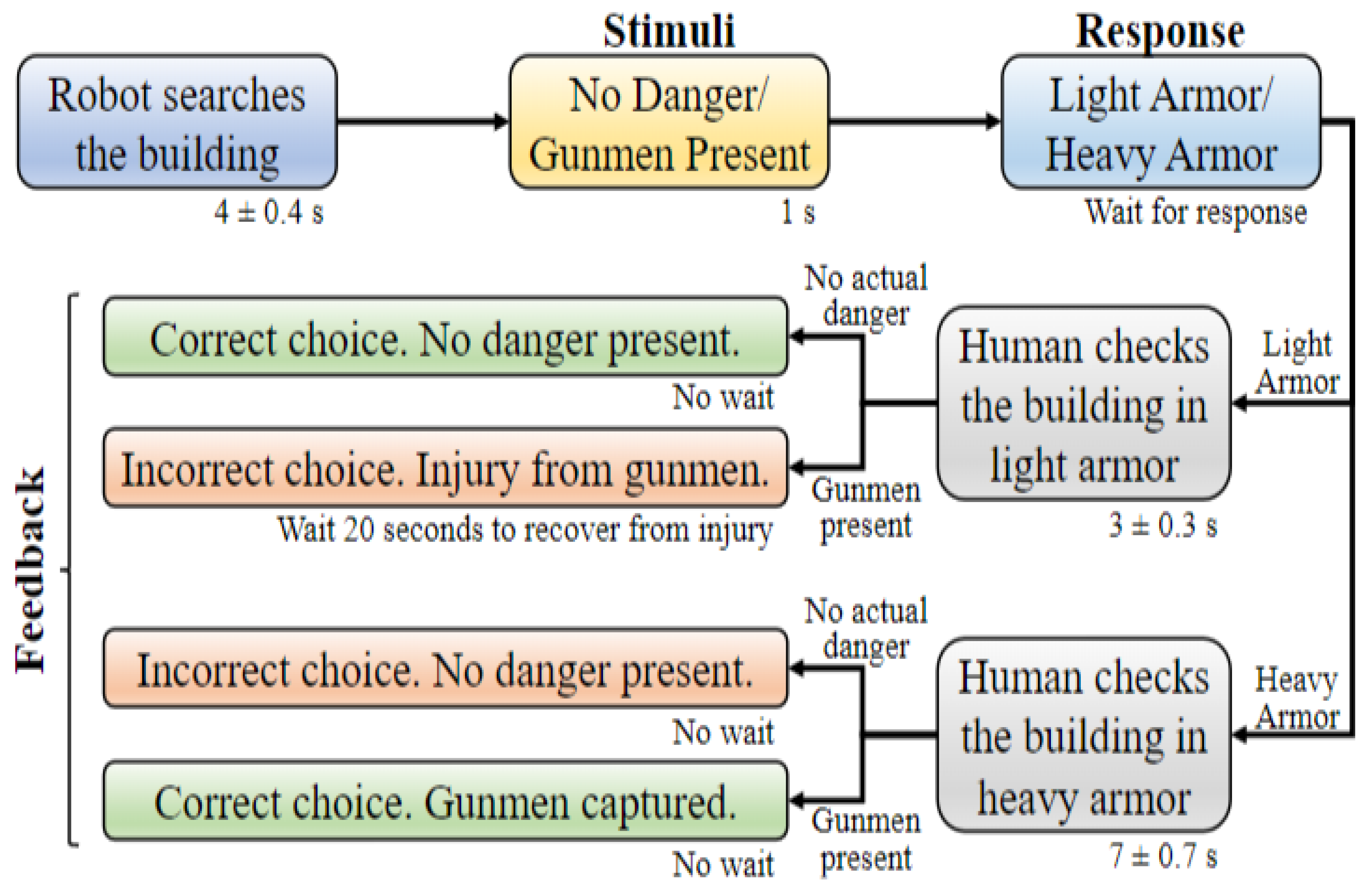

The instructional mission, which consisted of six trials, was performed by the participants prior to beginning the main experiment so they could become familiar with the research interface and the three levels of transparency. Each participant received the same tutorial assignment. The order of the missions for each transparency level was randomized among participants to minimize any potential biases and lessen the impact of factors like the order in which the missions were carried out. In the study, participants were asked to analyze robot reports regarding the presence or absence of gunmen in a building. The accuracy of the robot’s recommendations was 70%, and when the robot made a mistake, it was equally likely to be a false alarm or a miss. The sequence of events in each trial is depicted in

Figure 5 [

16].

Most existing trust models [

21] in human-robot interaction (HRI) are designed for specific types of interactions or robotic agents, making it difficult to compare their accuracy. This calls for the creation of a general HRI trust model that can be used in a variety of robotic domains, doing away with the necessity to create unique models of trust for each one.

Trust measurement methods used in fields like psychology and sociology, such as physiological indicators and objective measures like trust games, can be adapted for HRI to develop a trust model that is independent of the numerous factors influencing trust. Henceforth, development of trust models [

21] in human-robot interaction would not be impacted by the emergence of new factors that affect trust in existing or new robotic domains. This implies that existing trust models can be applied across different domains in the continuously evolving field of robotics, eliminating the need to create new trust models for each new domain.

Within HRI’s domain [

22,

23,

24], trust is a multifaceted notion that can be divided into two categories: relation-based trust and performance-based trust. A more encompassing definition of trust is required since current definitions from other domains do not adequately convey the multifaceted nature of trust within HRI.

Additionally, while there are studies on trust violation and repair, there is a need for research exploring the dynamics of trust loss and repair over time, particularly in relation to different types of failures and trust repair strategies. This raises questions [

22,

23,

24] about the impact of increasing familiarity with a robotic agent on trust loss due to robot failure, as well as the effectiveness of trust repair strategies in long-term interactions. It also highlights the lack of existing trust models that can be applied across different robotic tasks and domains, hindering the evaluation and comparison of trust models. Notably, this suggests the potential use of trust measurement methods from other fields, such as psychology and sociology, to accurately assess trust in human-robot interaction and develop trust models independent of various influencing factors.

Existing trust models in HRI [

22,

23,

24] are often specific to certain types of interactions, tasks, or robotic agents, making them difficult to compare or apply to different domains. This lack of a general trust model hinders the evaluation and development of trust models in HRI. It would be unnecessary to develop new models for every new robotic activity if there was a universal trust model that could be used across different robotic activities and domains. Many disciplines, including psychology, sociology, and physiology, are interested in the concept of trust. In these domains, trust is measured using a variety of indicators, including objective evaluations like trust games and physiological measurements. By using these measurement techniques, trust in HRI can be assessed more accurately, circumventing the drawbacks of existing techniques, and aiding in the development of trust models that are not influenced by a variety of variables.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

The goal of the current study is to use robust IG approaches to analyze info-geometrically HTBFC. To facilitate new innovative analysis of HTBFC performance and to enable relativistic analysis of its related manifold, IG is included in HTBFC theory.

This current study’s arising open problems are:

How feasible is it to calculate the inverse FIM (c.f., (19)) in four dimensions?

Having solved open problem 1, can we proceed with this revolutionary IG analysis to obtain the exact form of [] (c.f., (19)) for the five-dimensional HTBFC manifold?

-

Assuming the solvability of open problem 2, is it possible to employ this influential IG approach to analyse the dynamics of Human- Driven vehicles?

Future research pathways include finding answers to these open problems.

References

- I. A. Mageed, Y. Zhou, Y. Liu, and Q. Zhang, "Towards a Revolutionary Info-Geometric Control Theory with Potential Applications of Fokker Planck Kolmogorov(FPK) Equation to System Control, Modelling and Simulation," 2023 28th International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC), Birmingham, United Kingdom,2023,pp.1-6,doi: 10.1109/ICAC57885.2023.10275271. [CrossRef]

- F. Belliardo and V. Giovannetti, “Incompatibility in quantum parameter estimation”, New Journal of Physics, vol.23, no. 6, 2021, p. 063055. [CrossRef]

- S. Eguchi and O. Komori, “ Minimum Divergence Methods in Statistical Machine Learning”, Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022.

- A. Mageed, Q. Zhang, T. C. Akinci, M. Yilmaz and M. S. Sidhu, "Towards Abel Prize: The Generalized Brownian Motion Manifold’s Fisher Information Matrix With Info-Geometric Applications to Energy Works," 2022 Global Energy Conference (GEC), Batman, Turkey, 2022, pp. 379-384. [CrossRef]

- X. J. Yang et al, “ Toward quantifying trust dynamics: How people adjust their trust after moment-to-moment interaction with automation,”,Human Factors, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Kondor and S. Trivedi, “On the Generalization of Equivariance and Convolution in Neural Networks to the action of Compact Groups,”, Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, PMLR 80, 2018.

- A. Mageed, X. Yin, Y. Liu and Q. Zhang, "Z(a,b) of the Stable Five-Dimensional M/G/1 Queue Manifold Formalism’s Info- Geometric Structure with Potential Info-Geometric Applications to Human Computer Collaborations and Digital Twins," 2023 28th International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC), Birmingham, United Kingdom, 2023, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- I.A.Mageed and D. D. Kouvatsos, “ The Impact of Information Geometry on the Analysis of the Stable M/G/1 Queue Manifold,” In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems - ICORES, ISBN 978-989-758- 485-5, vol. 1, 2021, p. 153-160. [CrossRef]

- N. Kousi., et al, “ Task Allocation: Contemporary Methods for Assigning Human–Robot Roles,” The 21st Century Industrial Robot: When Tools Become Collaborators, 2022, p. 215-233.

- L. R. Soga et al, “Web 2.0-enabled team relationships: an actor-network perspective,” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, vol. 30, no. 5, 202, p. 639-652. [CrossRef]

- L. Simon et al, “How humans comply with a (potentially) faulty robot: Effects of multidimensional transparency,”, IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Systems, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Lee and K. A. See, “Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance,” Human Factors, J. Human Factors Ergonom. Soc., vol. 46, no. 1,pp. 50–80, 2004. [CrossRef]

- T. B. Sheridan and R. Parasuraman, “Human-automation interaction,” Rev. Human Factors Ergonom., vol. 1, no. 1, 2005, pp. 89–129. [CrossRef]

- G. and G. A. Jamieson, “ Human performance benefits of the automation transparency design principle: Validation and variation,” Human factors, vol. 63, no. 3, 2021, p. 379-401.

- T. O’Neill et al, “ Human–autonomy teaming: A review and analysis of the empirical literature,” Human factors, vol. 64, no. 5, 2022, p. 904-938. [CrossRef]

- K. Akash et al, “Human trust-based feedback control: Dynamically varying automation transparency to optimize human-machine interactions,” IEEE Control Systems Magazine, vol. 40, no. 6, 2020, p. 98-116. [CrossRef]

- L. Han et al, “ Analysis of Traffic Signs Information Volume Affecting Driver’s Visual Characteristics and Driving Safety,” International journal of environmental research and public health, vol. 19, no. 16, 2022, p. 10349. [CrossRef]

- K. Akash, K. Polson, T. Reid, and N. Jain, “Improving human–machine collaboration through transparency-based feedback—Part I: Human trust and workload model,” in Proc. 2nd IFAC Conf. Cyber-Physical & Human-Systems, Miami, FL,2018, pp. 315–321. [Online].Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405896319300308.

- K. Akash, T. Reid, and N. Jain, “Improving human-machine collaboration through transparency-based feedback—Part II: Control design and synthesis,” in Proc. 2nd IFAC Conf. Cyber-Physical & Human-Systems, Miami, FL, 2018, pp. 322–328. [Online].Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S240589631930028X.

- Q.Han et al, “Berry–Esseen bounds for Chernoff-type nonstandard asymptotics in isotonic regression,” The Annals of Applied Probability, vol. 32, no. 2, 2022, p. 1459-1498.

- Z. R. Khavas, S. R. Ahmadzadeh, and P. Robinette P, “ Modeling trust in human-robot interaction: A survey,” In International conference on social robotics, 2020, p. 529-541. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Z. R. Khavas, “ A review on trust in human-robot interaction,” 2021, arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.10045.

- Q. Wang, D. Liu D, M. G. Carmichael, S. ldini S, and C. T. Lin, “ Computational model of robot trust in human co-worker for physical human-robot collaboration,” IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 7, no. 2, 2022, p. 3146-3153. [CrossRef]

- S. Aldini et al, “Effect of mechanical resistance on cognitive conflict in physical human-robot collaboration,” Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2019, pp. 6137–6143.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).