1. Introduction

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, representing about 30-40% of cases [

1,

2,

3]. This aggressive form of lymphoma exhibits significant heterogeneity in its pathogenesis. Approximately 60% of patients respond positively to first-line treatment, while 25% experience relapse[

4,

5]. DLBCL is classified into two main subtypes based on the cell of origin: germinal center (GCB) and non-germinal center (ABC)[

6]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) also plays a crucial role in DLBCL pathogenesis. The TME is composed of immune system and stromal cells, including T and B lymphocytes, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs), natural killer cells (NK), and dendritic cells (DCs)[

7,

8,

9]. Additionally, stromal cells such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), extracellular matrix (ECM), mesenchymal cells, endothelial cells, pericytes, adipocytes, and various secretory molecules such as growth factors, chemokines, and cytokines are present. All these cells interact with each other in complex ways to form the TME, which supports the growth and survival of neoplastic cells[

7,

10]. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are critical components of the TME. They interact with various factors in the microenvironment and can be classified into two types, M1 (classically activated macrophages) and M2 (alternatively activated macrophages). M2 TAMs have been implicated in the pathogenesis of B lymphoproliferative diseases such as DLBCL. They promote tumor cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, ECM remodeling, immunosuppression, and inhibition of phagocytosis[

11,

12]. The activation of M2 TAMs that express CD163 and CD204 is mediated by cytokines such as IL10 and TGF-β, leading to IL-10secretion [

13]. CD163, also known as M130 and p155, is a scavenger receptor and member of the cysteine-rich family[

14,

15,

16]. It serves as a monocyte/macrophage-specific membrane marker, and is particularly recognized as a marker for alternatively activated or anti-inflammatory macrophages, as described by Abraham and Drummond (2006) and Komohara et al. (2006)[

17,

18]. CD163 is an extracellular protein that, undergoes ectodomain shedding, resulting in the release of its extracellular portion, sCD163, into the bloodstream as a soluble protein. Indeed, sCD163 levels increase significantly due to metalloproteinase-mediated cleavage near the cell membrane during these processes in response to oxidative stress, prostaglandin F2a stimulation, or activation of Fc gamma receptors TLR1, 2, 5, or 6[

19,

20]. However, the precise function of sCD163 remains unclear. Understanding the roles of TAMs and other cells in the TME is essential for a better understanding of DLBCL pathophysiology and for developing effective therapies.

The absence of established prognostic indicators and biomarkers in the guidelines for DLBCL therapeutic strategies has prompted the need for new research in this area. Significant development in the field of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) treatment was the incorporation of the monoclonal antibody anti-CD20 rituximab (R) into the conventional chemotherapy regimen CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) and the recent addition of anti-CD79b polatuzumab (Pola)[

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. R-CHOP therapy is the first-line treatment for DLBCL. The updated guidelines now differentiate between early and late relapse[

4,

5,

22,

26]. It is widely accepted that drug resistance is the primary cause of refractoriness in DLBCL[

27]. The tumor microenvironment is a key factor in DLBCL progression, and the interaction between DLBCL cells and various components and vessels in the environment is closely linked to drug resistance[

27]. The research carried out by Xu-Monette et al. attempted to determine the levels of immune markers, such as PD-1, PD-L1, PD-L2, and CD20, in tumors and their surrounding environment[

28,

29]. It was shown that high expression of PD-1 in immune cells, including T cells, NK cells, and phagocytes in the microenvironment, is associated with poor prognosis[

29]. Furthermore, it was reported that antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity was inhibited by macrophages and neutrophils, which reduced the anti-tumor potential of NK cells by releasing reactive oxygen species (ROS)[

27,

30]. Alternative mechanisms of resistance include complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), which is regulated by the increased expression of complement regulatory proteins, downregulation of CD16, and regulation of CD20 expression by various epigenetic and transcription factors[

31,

32,

33]. Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) plays a role in regulating the BCR signaling pathway, while nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) acts as a downstream transcription factor of BTK[

34]. Activation of NF-κB and BCR signaling, driven by various factors, plays a crucial role in the development of resistance[

28,

35]. However, there are currently no known prognostic indicators for early relapse in patients who have achieved complete response. It was therefore the objective of this study to investigate the impact of the burden of M2 CD163 positive tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) on overall survival and early relapses and to evaluate potential subgroups of patients through the serum levels of the soluble receptor CD163 (sCD163).

2. Materials and Methods

We retrospectively included DLBCL patients diagnosed in our unit from 2010 to 2023 who had available frozen sera kept from diagnosis before treatment and who were willing to provide informed consent for the study, with at least 1 year of follow-up after the diagnosis. The DLBCL diagnoses of the included patients were based on the latest WHO classification and the ICC International Classification including DLBCL NOS, GC DLBCL, ABC DLBCL, Primary Large B-cell lymphomas of immune-privileged sites (CNS, testis), primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type, EBV-positive DLBCL, DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation, primary mediastinal LBCL, Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma, ALK-pos LBCL, plasmablastic lymphoma, intravascular LBCL, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma, HGBCL with MYC and BCL2 rearrangement, and high-grade transformation of indolent B-cell lymphomas. The analysis also focused on immunohistochemistry of tissue biopsy at diagnosis for the presence of bcl6, bcl2, cmyc, cyclinD1, pax5, eber, and the immunophenotype of neoplastic B-lymphocytes for the expression of cd30, cd10, cd3, and cd5. Additionally, full blood counts, including hemoglobin, total white blood cell count, absolute lymphocyte count, and absolute monocyte count, as well as laboratory findings such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), B2 microglobulin, gamma globulin, serum calcium, and serum albumin values were retrieved from patients’ medical files.

Forty serum samples were collected at the time of the diagnosis. Patients were diagnosed with large B-cell lymphoma according to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) classification and the International Classification of Diseases (ICC). All of the patients were over the age of eighteen, and they had not received any prior treatment with corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or chemotherapy drugs.

Serum s-CD163 measurements were performed using frozen sera samples from 40 patients at the time of diagnosis and from 30 healthy individuals (HI). Measurements were done using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Human CD163 Quantikine, Duo-Set R&D Systems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the Human CD163 Immunoassay is a solid-phase ELISA designed to measure the levels of soluble human CD163 in cell culture, serum, and plasma. This assay is an 8-hour ELISA that utilizes natural human CD163. It can be used to determine CD163 concentrations in liquids. The method include reagent preparation, plate preparation, and samples determination. The microplate was pre-coated with a monoclonal antibody specific for human CD163 and incubated overnight. Standards and samples were then pipetted into the wells. After washing away the unbound substances, an enzyme-linked monoclonal antibody specific for human CD163 was added to the wells. This was followed by washing to remove any unbound antibody-enzyme reagent, and the substrate solution was then added to the wells. Color developed in proportion to the amount of CD163 bound in the initial step, and color development was stopped with the stop solution. The optical intensity of the color was measured using a microplate reader. All measurements were performed in duplicate. However, the present technique has certain limitations of reproducibility. In our experience, as the sample values exceeded the highest standard value, it was necessary to further dilute the sample with a calibrator diluent and repeat the assay.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS v.28 software. Kaplan-Meier curves depicted survival while the log-rank test was used to estimate the differences in outcomes between the subgroups that were studied. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The Mann-Whitney test was used for non-parametrical variables, and the x2 or t test for continuous variables.

3. Results

The 40 patients studied included 19 males and 21 females, with a mean age of 61.74 years (range, 18–93 years). The mean follow-up duration was 4 years (range, 2–170 months). Thirty patients were diagnosed with primary DLBCL, and ten with secondary large B-cell lymphoma. Of these, three patients were diagnosed with Ann Arbor stage I, four with stage II, nine with stage III, and twenty-four with stage IV. Twenty-three patients had a poor R-IPI prognostic score, whereas 17 had a good score; however, none of the patients had very good R-IPI scores. (

Table 1).

The first-line treatment for 27 patients consisted of the R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen (Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisolone). Nine patients received reduced-intensity chemotherapy regimens because of their advanced age or comorbidities. Four patients were treated with double monoclonal antibodies (anti-CD20 and anti-CD79b) in combination with chemotherapy (rituximab, polatuzumab, vedotin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisolone). A complete response was achieved in twenty-four (60%) patients and a partial response in five patients. In contrast, 11 (27,5%) were initially resistant and died within 12 months of diagnosis. (

Table 1). None of the responders died.

Upon analyzing the data for immunophenotyping, immunohistochemistry, and Han's algorithm, it was determined that 20 patients exhibited positive staining for bcl6 (cut off 30%) and bcl2 (cut off 50%). Seven patients displayed c-Myc staining with a cut-off of 40%, while three patients showed low expression of cmyc (0-39%). Additionally, MUM1/IRF4 and PAX5 positive staining was observed in 12 and 11 patients, respectively. Clonal B cells expressed CD10 in ten patients. In four patients, CD30 was positive, whereas one was positive for EBER. According to Han’s algorithm, in our patients, the cell of origin was classified as germinal center (GC) in 45% of the patients and non-germinal center (activated B cell [ABC]) in 55% of the patients (

Table 2). Complete immunophenotyping was not reported in 16 patients for any of the immunohistochemical staining outcomes. (

Table 2). Four patients with ABC-type DLBCL and four with GCB-type DLBCL died. Likewise, two individuals with elevated c-myc levels and two with low c-myc expression levels passed away. In our study, immunohistochemical stainings for bcl2, bcl6, cmyc, PAX5, and MUM1 was not associated with any clinical or laboratory factor, whereas CD10 phenotyping was associated with extralymphatic disease (p value 0,011). In the IHC panel, c-Myc was associated with bcl6, PAX5, CD10, and CD30 expression (p value 0,002, 0,011, 0,008 and 0,013, respectively). In addition, PAX5 correlated with c-myc, bcl2 and cyclinD1 (p value 0,011, 0,005 and 0,003, respectively) (

Table 2).

According to the laboratory results obtained at the time of diagnosis, the average levels of hemoglobin, white blood cells, lymphocytes, and monocytes were found to be 11.68 gr/dl, 7.14 K/μL, 1.53 K/μL, and 0.57 K/μL, respectively. Notably, 67.5% of the patients exhibited monocytosis, while 25% had lymphopenia, with major lymphopenia (absolute lymphocytes below 0.5 K/μL) present in 10% of the patients. Anemia was associated with lymphopenia and monocytosis (p value 0, 002 and 0, 009, respectively). Additionally, the average B2 microglobulin was 3,78 mg/L with almost half (52,5%) of the patients having abnormal levels. B2 microglobulin level was associated with advanced Ann Arbor staging (p value 0,025) and extranodal disease (p value 0,011). The average LDH level was 476 U/L, with 65% of patients exhibiting abnormal levels. Furthermore, 7.5% of the patients had LDH levels above of 1000 U/L. Hypercalcemia and hypogammaglobulinemia were presented in 7,5% and 10% of the patients, respectively. All patients with hypercalcemia and hypogammaglobulinemia had stage III or IV disease and had poor R-IPI scores.

Table 3.

Laboratory data of all patients at the time of diagnosis.

Table 3.

Laboratory data of all patients at the time of diagnosis.

| Laboratory Data |

Average count |

Total N=40

Patient N (n %) |

Hb (gr/dl)

Anemia |

11,68 |

23 (57,5%) |

Absolute count WBC (K/μl)

Absolute count Lymphocytes (K/μl)

Lymphopenia (<1,2 K/μL) |

7,14 |

|

| 1,53 |

10 (25%) |

Absolute count Monocytes (K/μl)

Monocytes > 0,5 K/μl

LDH (U/L)

UNL (>235 U/L)

B2 Microglobulin (mg/L)

UNL (>2,4 mg/L)

Calcium serum

Hypercalcemia |

0,57 |

27 (67,5%) |

| 476 |

26 (65%) |

| 3,78 |

21 (52,5%) |

| 9,5 |

3 (7,5%) |

Gamma Globulin

Hypogammaglobulinemia |

11,1 |

4 (10%) |

Initial analysis of the data revealed that all patients diagnosed with DLBCL displayed heightened levels of serum soluble receptor CD163. thus, subsequent dilutions of the samples were needed. The dilution ratio used was 1:4. Median s CD163 value was 126052 pg/ml (range: 92056 to 164912 pg/ml), which was statistically significantly higher than the median value of 26826 pg/ml (ranging from 11831 to 97286 pg/ml) in healthy individuals (p<0,001). The patients were then divided into two groups based on their average values, with one group having values lower than the median and the other having values equal to or above the median. Patients with higher serum sCD163 levels showed a trend for more unfavorable overall survival (p-value 0.18). Specifically, the median overall survival for patients with high and low sCD163 levels was 19,8 months (1,6 years) and 46,23 months (3,8 years), respectively.

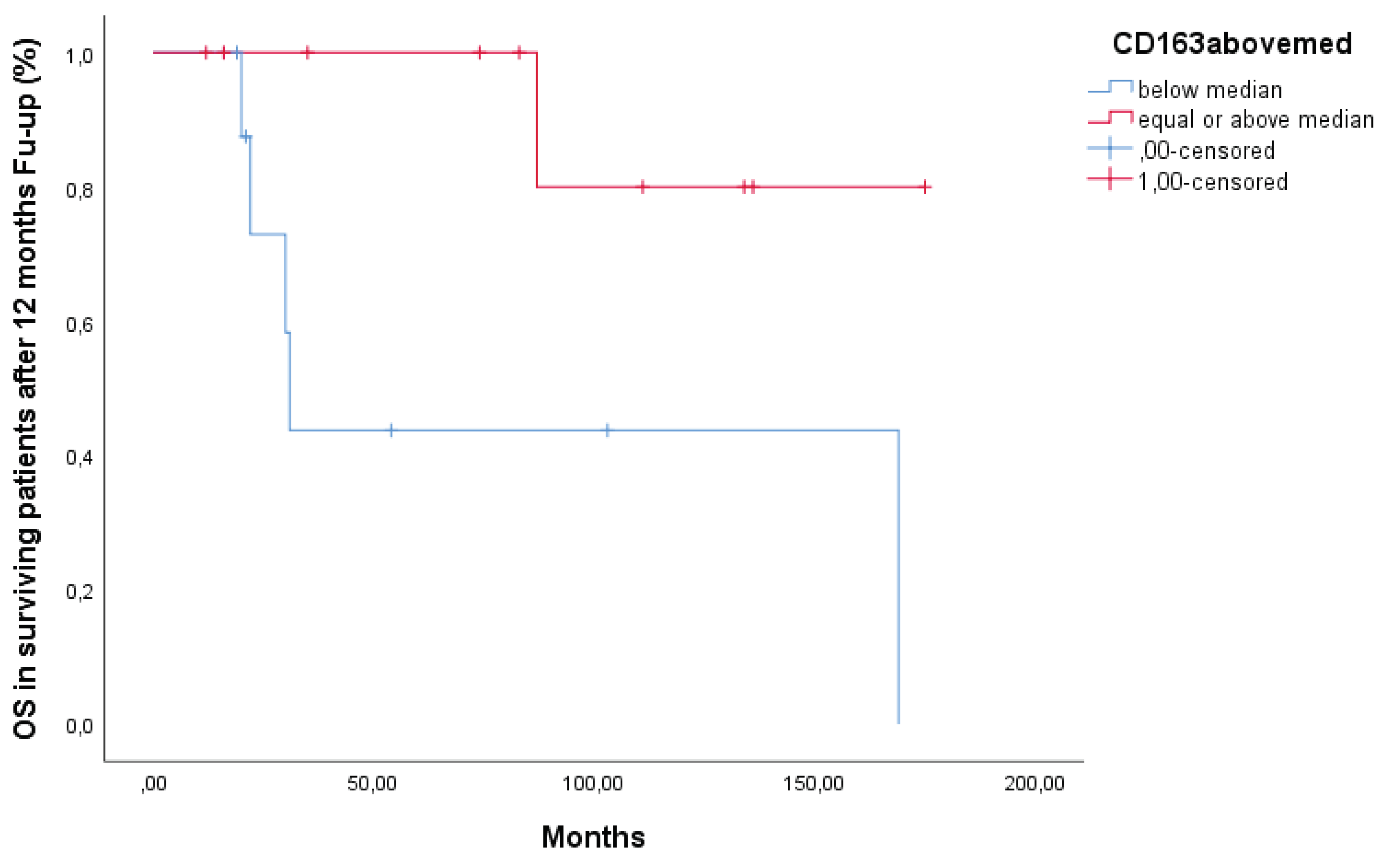

A sub-analysis was then performed on patients that were alive after the 1st year (N=29), thus excluding from the analysis the 11 deceased patients who were primary resistant. The median overall survival of this sub-cohort was 4.8 years with a 5-year survival rate of 40%. Patients with serum sCD163 below median had a better overall survival than patients with levels above median (Figure 2) (p =0.03).

Figure 1.

Overall Survival Of Patients Alive After 12 Months Follow-Up.

Figure 1.

Overall Survival Of Patients Alive After 12 Months Follow-Up.

Because of the small number of patients and of events, we failed to prove any prognostic value of serum sCD163 levels regarding progression-free survival (PFS), or time to next treatment (TTT), and various laboratory and clinical factors. However, no statistically significant correlation was found and these factors. A possible association was observed between levels of serum sCD163 and PAX5 immunohistochemical staining (p=0.016) but the number of cases studied is too small to reach conclusion.

4. Discussion

Our study included 40 patients (19 men and 21 women) with a median age of 62 years (range, 18–93 years), of whom four were older than 80 years. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical impact of serum sCD163 levels in patients with DLBCL at diagnosis. The outcomes of our patient population were retrospectively assessed, revealing a high prevalence of advanced staging (Ann Arbor IV) and poor R-IPI scores in 60% of cases. Additionally, 45% had extranodal disease and 20% exhibited bone marrow infiltration. This patients’ population typically demonstrates an aggressive clinical course, necessitating additional prognostic factors to distinguish them as. Hopefully, effective management strategies can still be implemented. In spite of their very bad prognosis, 60% of patients achieved a complete response while 27,5% were refractory to first-line treatment. Notably, 27 patients received R-CHOP, 4 received R-Pola-CHP, and 9 received reduced-intensity chemotherapy due to advanced age or comorbidities. The past twenty years Rituximab-based chemoimmunotherapy has changed DLBCL treatment landscape, and approximately 50% to 60% of patients are cured with first-line treatment but as reported by Sarkozy C. in 2018 and Westin J. in 2022, 10% of patients are refractory to first-line treatment and 25% experience a relapse. Indeed, our cohort is not representative of previously published data as more than half of the patients were in advanced stage, and consequently, 27.5% of them were refractory to therapy; a percentage significantly higher than the reported one in the literature. We administered the immunochemotherapy protocol R-Pola-CHP to four recently diagnosed patients with advanced-stage disease and poor R-IPI score, based on the phase III POLARIX trial [

4,

21,

25,

26]. Polatuzumab vedotin combined with R-CHP in frontline treatment of DLBCL was recently approved and produced a significant improvement of the 2-year PFS compared to standard of care R-CHOP [

25,

36,

37,

38]. None of these four patients had relapsed to date. Moreover, the molecular subgroups of DLBCL display notably distinct biological characteristics, therapy responsiveness, and overall survival, which are determined by the cell of origin and serve as independent prognostic factors, as the ABC type has a shortened 5-year PFS [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. The majority of our patients’ series displayed an ABC-type DLBCL, observed in 32, 5% of the patients while the GCB DLBCL type was represented in only 27% of patients. Unfortunately, the remaining patients did not have an adequate immunohistochemical panel to establish the cell of origin. ABC type compared to GCB type did not have a significant statistical relationship to overall survival, progression free, and time to next treatment in this series. MYC rearrangement, as confirmed by FISH, was detected in seven patients and showed no statistically significant association with other clinical or laboratory parameters. Patients laboratory testing included a complete blood cell (CBC) count and a metabolic panel. Anemia, thrombocytopenia, and/or leukopenia may indicate bone marrow infiltration. In our study, there was a correlation between anemia and lymphopenia as well as with an increased monocyte count. Notably, thrombocytopenia was not detected, and leukocytopenia was observed in four patients; it was not correlated with bone marrow infiltration. The literature contains conflictuous data referring to lymphopenia as an independent prognostic factor[

44,

45]. This was not the case in the present study, lymphocytopenia was not associated with overall survival, advanced-stage disease, or a poor R-IPI (data not shown). In agreement, Zatreh's et al study, reported that lymphopenia was not a significant predictor of overall survival in DLBCL [

46]. Furthermore, in our study, we observed that patients with elevated serum calcium and decreased gamma globulin levels had advanced-stage disease and poor R-IPI score. These findings are in agreement with published studies, indicating that both markers are predictors of aggressive disease[

47,

48,

49,

50,

51].

Typically, the soluble receptor CD163 rises in the bloodstream in response to oxidative stress, prostaglandin stimulation, or Fc gamma receptors. All patients with DLBCL had elevated levels of the serum soluble receptor CD163. Sandwich ELISA results showed that sample values exceeded the highest standard and indeed healthy individuals. Therefore, we performed additional dilutions of the samples and repeated the assay. The dilution ratio was 1:4, and all sample values of the patients were elevated compared to those of healthy controls. The observation that all samples exhibited remarkably high levels of soluble receptor CD163, irrespective of stage, age, performance status, B symptoms, extranodal sites, and tumor burden, is noteworthy. This finding implies that elevated levels of soluble receptor CD163 may be a common feature among patients with DLBCL. In recent years, multiple studies have demonstrated the roles of TAMs and CD163 in the pathogenesis of neoplasms (solid and hematopoietic). Hematopoietic malignancies may be implicated in elevated CD163 expression, including T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, acute myeloid leukemia, and classical Hodgkin lymphoma [

18,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. In most studies, high CD163 expression was correlated with an inferior prognosis. The influence of CD163 expression in non-Hodgkin ’s lymphoma, specifically in DLBCL, mantle cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and T lymphoma, has recently been explored. Controversial findings as well as significant heterogeneity have been reported and highlighted in relevant meta-analyses [

59,

60]. The majority of studies have compared the density of immunohistochemical staining for CD163 and CD68 in tissue biopsy. The use of blood-based metric values to assess the burden of M2 TAMs (alternatively activated macrophages) has recently been established and tested. In a recent publication by Xiaoqing Sun, data on the utility of Siglec-5/CD163 as an independent biomarker were reported [

61]. In addition, Nikkarinen et al. reported the impact of serum soluble CD163 in patients with mantle cell lymphoma treated with immunotherapy [

62]. In their studies, both Xiaoqing and Nikkarinen used serum soluble CD163 levels as us, instead of immunohistochemical staining, which has been previously utilized in research studies. This technique for determining CD163 levels is currently being explored and appears to provide useful insights regarding the presence of M2 TAMS in the TME.

With this recent approach, our goal was to investigate the relationship between serum levels of the soluble receptor CD163 and survival, as well as its clinical relevance, in individuals with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. In the whole cohort, patients with serum sCD163 levels above median had a trend towards unfavorable overall survival (OS). However, in patients alive after 12 months of follow-up, those with serum sCD163 levels above the median had a significantly worse overall survival than patients with serum sCD163 levels below the median (p=0.03), as shown in

Figure 1, suggesting a role of TAMs in late relapse.

Serum sCD163 can be easily determined by ELISA and the procedure is not so expensive; eventually, high-risk patients could be further identified based on sCD163 levels to guide treatment decisions and eventually administered some kind of maintenance in patients with increased sCD163 levels. Identifying disease-related biomarkers has emerged as a crucial aspect of research aimed at facilitating the diagnosis and prognosis of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL). Biomarkers serve as critical elements that inform guidelines for risk assessment, prognostic prediction, treatment response evaluation, and disease progression monitoring. Existing biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis in DLBCL are B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2), B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6), MYC, Nuclear Factor kappa-B (NFk-b), and mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2)[

28]. According to Camicia R's comprehensive review of novel drug targets for personalized precision medicine in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, there are three types of drug resistance that can be identified: genetic resistance, resistance to chemotherapy, and tumor microenvironment (TME) cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance[

63]. Based on our results and previously published data, we hypothesized that excessive activation of TAMs, reflected by sCD163 secretion, contributes to disease relapse. Indeed, it is important to note that our and other observations are based on preliminary data (a small number of patients) and necessitate further investigation and identification of specific subgroups.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found that serum soluble CD163 may serve as a novel prognostic indicator in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Specifically, patients with lower levels of soluble CD163 may have a better prognosis, whereas those with higher levels may be more likely to experience resistance or recurrence. The levels of soluble CD163 reflect the burden of TAMs in the tumor microenvironment, whose role have not been fully elucidated yet.

Further research is necessary to validate our results.

Author Contributions

Design study, M-C.K. and N.K.; methodology (cytokine measurements), A.K. and A-I. Gk., A. Gk., Th.Tr.; validation, A.K., and M-C.K.; formal analysis, M-C.K.; resources, data curation, A.K., A-I. Gk., A. Gk., M.P., A.A., V. B.; writing—review and editing, A.K.; supervision, M-C.K.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Morton, L.M.; Wang, S.S.; Devesa, S.S.; Hartge, P.; Weisenburger, D.D.; Linet, M.S. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood 2006, 107, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyatskin, I.L., A.S. Artemyeva, and Y.A. Krivolapov, [Revised WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 2017 (4th edition):lymphoid tumors]. Arkh Patol, 2019. 81(3): p. 59-65.

- Swerdlow, S.H., et al., The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood, 2016. 127(20): p. 2375-90.

- Westin, J. and L.H. Sehn, CAR T cells as a second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma: a paradigm shift? Blood, 2022. 139(18): p. 2737-2746.

- Flowers, C.R. and O.O. Odejide, Sequencing therapy in relapsed DLBCL. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2022. 2022(1): p. 146-154.

- Hans, C.P.; Weisenburger, D.D.; Greiner, T.C.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Delabie, J.; Ott, G.; Müller-Hermelink, H.K.; Campo, E.; Braziel, R.M.; Jaffe, E.S.; et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004, 103, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennishi, D., The biology of the tumor microenvironment in DLBCL: Targeting the "don't eat me" signal. J Clin Exp Hematop, 2021. 61(4): p. 210-215.

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X. Targeting the tumor microenvironment in B-cell lymphoma: challenges and opportunities. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, W.L.; Ansell, S.M.; Mondello, P. Insights into the tumor microenvironment of B cell lymphoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haro, M.; Orsulic, S. A Paradoxical Correlation of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts With Survival Outcomes in B-Cell Lymphomas and Carcinomas. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-L.; Shi, Z.-H.; Wang, X.; Gu, K.-S.; Zhai, Z.-M. Tumor-associated macrophages predict prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and correlation with peripheral absolute monocyte count. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Li, H.; Shi, Y.; Wang, D.; Gong, J.; Xun, J.; Zhou, S.; Xiang, R.; Tan, X. M2 tumour-associated macrophages contribute to tumour progression via legumain remodelling the extracellular matrix in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasingam, S.D.; Citartan, M.; Thang, T.H.; Mat Zin, A.A.; Ang, K.C.; Ch'ng, E.S. Evaluating the Polarization of Tumor-Associated Macrophages Into M1 and M2 Phenotypes in Human Cancer Tissue: Technicalities and Challenges in Routine Clinical Practice. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, C.L., Chapter Six - Biomarkers in Acute Kidney Injury, in Biomarkers of Kidney Disease (Second Edition), C.L. Edelstein, Editor. 2017, Academic Press. p. 241-315.

- Etzerodt, A.; Moestrup, S.K. CD163 and Inflammation: Biological, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Aspects. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 2352–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabriek, B.O.; Van Bruggen, R.; Deng, D.M.; Ligtenberg, A.J.M.; Nazmi, K.; Schornagel, K.; Vloet, R.P.M.; Dijkstra, C.D.; Van Den Berg, T.K. The macrophage scavenger receptor CD163 functions as an innate immune sensor for bacteria. Blood 2009, 113, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, N.G. and G. Drummond, CD163-Mediated hemoglobin-heme uptake activates macrophage HO-1, providing an antiinflammatory function. Circ Res, 2006. 99(9): p. 911-4. [CrossRef]

- Komohara, Y., et al., Clinical significance of CD163⁺ tumor-associated macrophages in patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Cancer Sci, 2013. 104(7): p. 945-51.

- Etzerodt, A.; Berg, R.M.G.; Plovsing, R.R.; Andersen, M.N.; Bebien, M.; Habbeddine, M.; Lawrence, T.; Møller, H.J.; Moestrup, S.K. Soluble ectodomain CD163 and extracellular vesicle-associated CD163 are two differently regulated forms of ‘soluble CD163’ in plasma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, H.J., Soluble CD163. Scand J Clin Lab Invest, 2012. 72(1): p. 1-13.

- Coiffier, B., et al., Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood, 2010. 116(12): p. 2040-5.

- Douglas, M. Polatuzumab Vedotin for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in Transplant-Ineligible Patients. J. Adv. Pr. Oncol. 2020, 11, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugtenburg, P.J. and P. Mutsaers, How I treat older patients with DLBCL in the frontline setting. Blood, 2023. 141(21): p. 2566-2575.

- Pfreundschuh, M.; Murawski, N.; Zeynalova, S.; Ziepert, M.; Loeffler, M.; Hänel, M.; Dierlamm, J.; Keller, U.; Dreyling, M.; Truemper, L.; et al. Optimization of rituximab for the treatment of DLBCL: increasing the dose for elderly male patients. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 179, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, H.; Morschhauser, F.; Sehn, L.H.; Friedberg, J.W.; Trněný, M.; Sharman, J.P.; Herbaux, C.; Burke, J.M.; Matasar, M.; Rai, S.; et al. Polatuzumab Vedotin in Previously Untreated Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2021, 386, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhu, J. Effectiveness and Safety of Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor-T Cell Immunotherapy in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 834113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusowska, A.; Kubacz, M.; Krawczyk, M.; Slusarczyk, A.; Winiarska, M.; Bobrowicz, M. Molecular Aspects of Resistance to Immunotherapies—Advances in Understanding and Management of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhi, N.; Tun, M.; Nagpal, P.; Inamdar, A.A.; Ayoub, N.M.; Siyam, N.; Oton-Gonzalez, L.; Gerona, A.; Morris, D.; Sandhu, R.; et al. Biomarkers and novel therapeutic approaches for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the era of precision medicine. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 4045–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu-Monette, Z.Y.; Xiao, M.; Au, Q.; Padmanabhan, R.; Xu, B.; Hoe, N.; Rodríguez-Perales, S.; Torres-Ruiz, R.; Manyam, G.C.; Visco, C.; et al. Immune Profiling and Quantitative Analysis Decipher the Clinical Role of Immune-Checkpoint Expression in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment of DLBCL. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gu, Y.; Chen, B. Drug-Resistance Mechanism and New Targeted Drugs and Treatments of Relapse and Refractory DLBCL. Cancer Manag. Res. 2023, ume 15, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.; Glennie, M. The mechanisms of action of rituximab in the elimination of tumor cells. Semin. Oncol. 2003, 30 (Suppl. S2), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ao, K.; Bao, F.; Cheng, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, S.; Xu, J.; Wu, Q. Development of a Bispecific Nanobody Targeting CD20 on B-Cell Lymphoma Cells and CD3 on T Cells. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiarska, M., et al., Molecular mechanisms of the antitumor effects of anti-CD20 antibodies. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed), 2011. 16(1): p. 277-306.

- Alas, S., C. Emmanouilides, and B. Bonavida, Inhibition of interleukin 10 by rituximab results in down-regulation of bcl-2 and sensitization of B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma to apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res, 2001. 7(3): p. 709-23.

- Tilly, H., et al., Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol, 2015. 26 Suppl 5: p. v116-25.

- Davis, J.A. , et al., Polatuzumab Vedotin for the Front-Line Treatment of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A New Standard of Care? J Adv Pract Oncol, 2023. 14(1): p. 67-72.

- Ho, R.S.; Launonen, A. Comparison of statistical methods for extrapolating survival in previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results based on the POLARIX study. J. Med Econ. 2023, 26, 1178–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Reagan, P.M.; Sehn, L.H.; Sharman, J.P.; Hertzberg, M.; Zhang, H.; Kim, A.I.; Herbaux, C.; Molina, L.; Maruyama, D.; et al. Subgroup analysis of elderly patients (pts) with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in the phase 3 POLARIX study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41 (Suppl. S16), 7518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuy, B.; Stewart, C.; Dunford, A.J.; Kim, J.; Kamburov, A.; Redd, R.A.; Lawrence, M.S.; Roemer, M.G.M.; Li, A.J.; Ziepert, M.; et al. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma are associated with distinct pathogenic mechanisms and outcomes. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.A.; Eisen, M.B.; Davis, R.E.; Ma, C.; Lossos, I.S.; Rosenwald, A.; Boldrick, J.C.; Sabet, H.; Tran, T.; Yu, X.; et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature 2000, 403, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.W.; Huang, D.W.; Phelan, J.D.; Coulibaly, Z.A.; Roulland, S.; Young, R.M.; Wang, J.Q.; Schmitz, R.; Morin, R.D.; Tang, J.; et al. A Probabilistic Classification Tool for Genetic Subtypes of Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma with Therapeutic Implications. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.; Wright, G.W.; Huang, D.W.; Johnson, C.A.; Phelan, J.D.; Wang, J.Q.; Roulland, S.; Kasbekar, M.; Young, R.M.; Shaffer, A.L.; et al. Genetics and Pathogenesis of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1396–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, S.E.; Barrans, S.L.; Beer, P.A.; Painter, D.; Smith, A.G.; Roman, E.; Cooke, S.L.; Ruiz, C.; Glover, P.; Van Hoppe, S.J.L.; et al. Targeted sequencing in DLBCL, molecular subtypes, and outcomes: a Haematological Malignancy Research Network report. Blood 2020, 135, 1759–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaulikar, D.; Choudhury, A.; Shadbolt, B.; Brown, M. Lymphocytopenia as a prognostic marker for diffuse large B cell lymphomas. Leuk. Lymphoma 2008, 49, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Wei, Y.; Huang, F.; Jing, H.; Xie, M.; Hao, X.; Feng, R. Lymphopenia predicts preclinical relapse in the routine follow-up of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma 2015, 56, 1261–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatreh, M., et al., Is Absolute Lymphocyte Count at Time of Diagnosis a Predictor of Overall Survival in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients? Blood, 2020. 136: p. 32.

- Abadi, U.; Peled, L.; Gurion, R.; Rotman-Pikielny, P.; Raanani, P.; Ellis, M.H.; Rozovski, U. Prevalence and clinical significance of hypercalcemia at diagnosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma 2019, 60, 2922–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauchy, A.; Kanagaratnam, L.; Quinquenel, A.; Gaillard, B.; Rodier, C.; Godet, S.; Delmer, A.; Durot, E. Hypercalcemia at diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is not uncommon and is associated with high-risk features and a short diagnosis-to-treatment interval. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 38, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.-H.; Kong, Y.-L.; Wang, L.; Zhu, H.-Y.; Li, X.-T.; Liang, J.-H.; Xia, Y.; Wu, J.-Z.; Fan, L.; Li, J.-Y.; et al. The prognostic roles of hypogammaglobulinemia and hypocomplementemia in newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma 2021, 62, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallis, R.M.; Rome, R.S.; Reagan, J.L. Mechanisms of Hypercalcemia in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and Associated Outcomes: A Retrospective Review. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018, 18, e123–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Mott, S.L.; McCarthy, A.N.; Syrbu, S.; Habermann, T.M.; Feldman, A.L.; Slager, S.L.; Nowakowski, G.; Witzig, T.E.; Farooq, U.; et al. Prevalence and the Impact of Hypogammaglobulinemia in Newly Diagnosed, Untreated Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. Blood 2019, 134 (Suppl. S1), 1604–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Gardner, D.; Reichard, K.K. CD163: A Specific Immunohistochemical Marker for Acute Myeloid Leukemia With Monocytic Differentiation. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2008, 16, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bächli, E.B.; Schaer, D.J.; Walter, R.B.; Fehr, J.; Schoedon, G. Functional expression of the CD163 scavenger receptor on acute myeloid leukemia cells of monocytic lineage. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 79, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugaya, M.; Miyagaki, T.; Ohmatsu, H.; Suga, H.; Kai, H.; Kamata, M.; Fujita, H.; Asano, Y.; Tada, Y.; Kadono, T.; et al. Association of the numbers of CD163+ cells in lesional skin and serum levels of soluble CD163 with disease progression of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2012, 68, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miari, K.E.; Guzman, M.L.; Wheadon, H.; Williams, M.T.S. Macrophages in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia: Significant Players in Therapy Resistance and Patient Outcomes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allah, M.Y.Y.A.; Fahmi, M.W.; El-Ashwah, S. Clinico-pathological significance of immunohistochemically marked tumor-associated macrophage in classic Hodgkin lymphoma. J. Egypt. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 32, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.A.S., et al., CD163 is a predictive biomarker for prognosis of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma in Saudi patients. Mol Clin Oncol, 2019. 11(1): p. 67-76.

- Hsi, E.D.; Li, H.; Nixon, A.B.; Schöder, H.; Bartlett, N.L.; LeBlanc, M.; Smith, S.; Kahl, B.S.; Leonard, J.P.; Evens, A.M.; et al. Serum levels of TARC, MDC, IL-10, and soluble CD163 in Hodgkin lymphoma: a SWOG S0816 correlative study. Blood 2019, 133, 1762–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Ma, S.; Sun, L.; Qin, Z. The prognostic value of tumor-associated macrophages detected by immunostaining in diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1094400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X., et al., The prognostic value of tumour-associated macrophages in Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology, 2020. 91(1): p. e12814.

- Sun, X.; Cao, J.; Sun, P.; Yang, H.; Li, H.; Ma, W.; Wu, X.; He, X.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; et al. Pretreatment soluble Siglec-5 protein predicts early progression and R-CHOP efficacy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Biomarkers Med. 2023, 17, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikkarinen, A.; Lokhande, L.; Amini, R.-M.; Jerkeman, M.; Porwit, A.; Molin, D.; Enblad, G.; Kolstad, A.; Räty, R.K.; Hutchings, M.; et al. Soluble CD163 predicts outcome in both chemoimmunotherapy and targeted therapy–treated mantle cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 5304–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camicia, R.; Winkler, H.C.; Hassa, P.O. Novel drug targets for personalized precision medicine in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a comprehensive review. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).