Submitted:

04 March 2024

Posted:

05 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

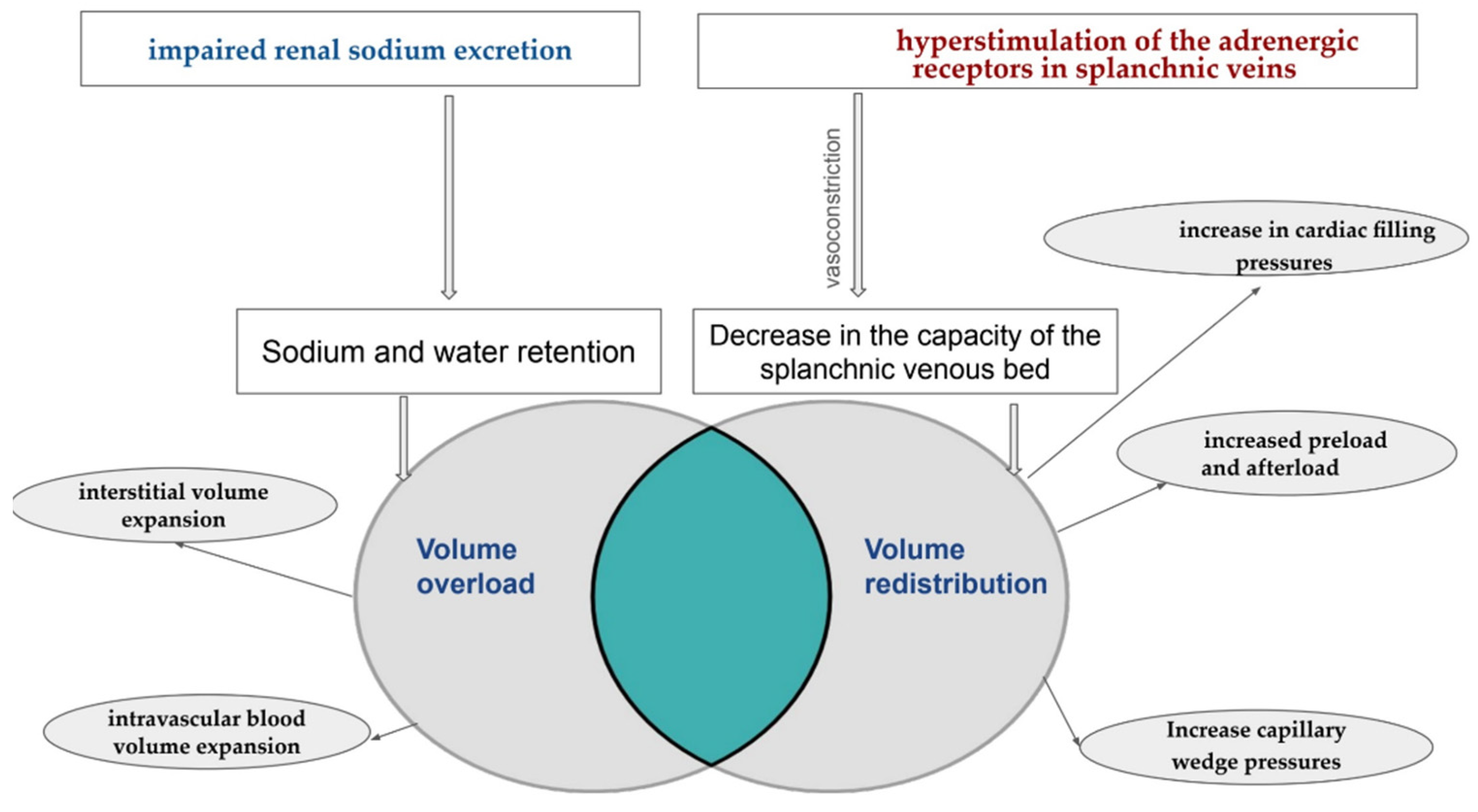

2. Understanding Congestion: Volume Overload or Volume Redistribution

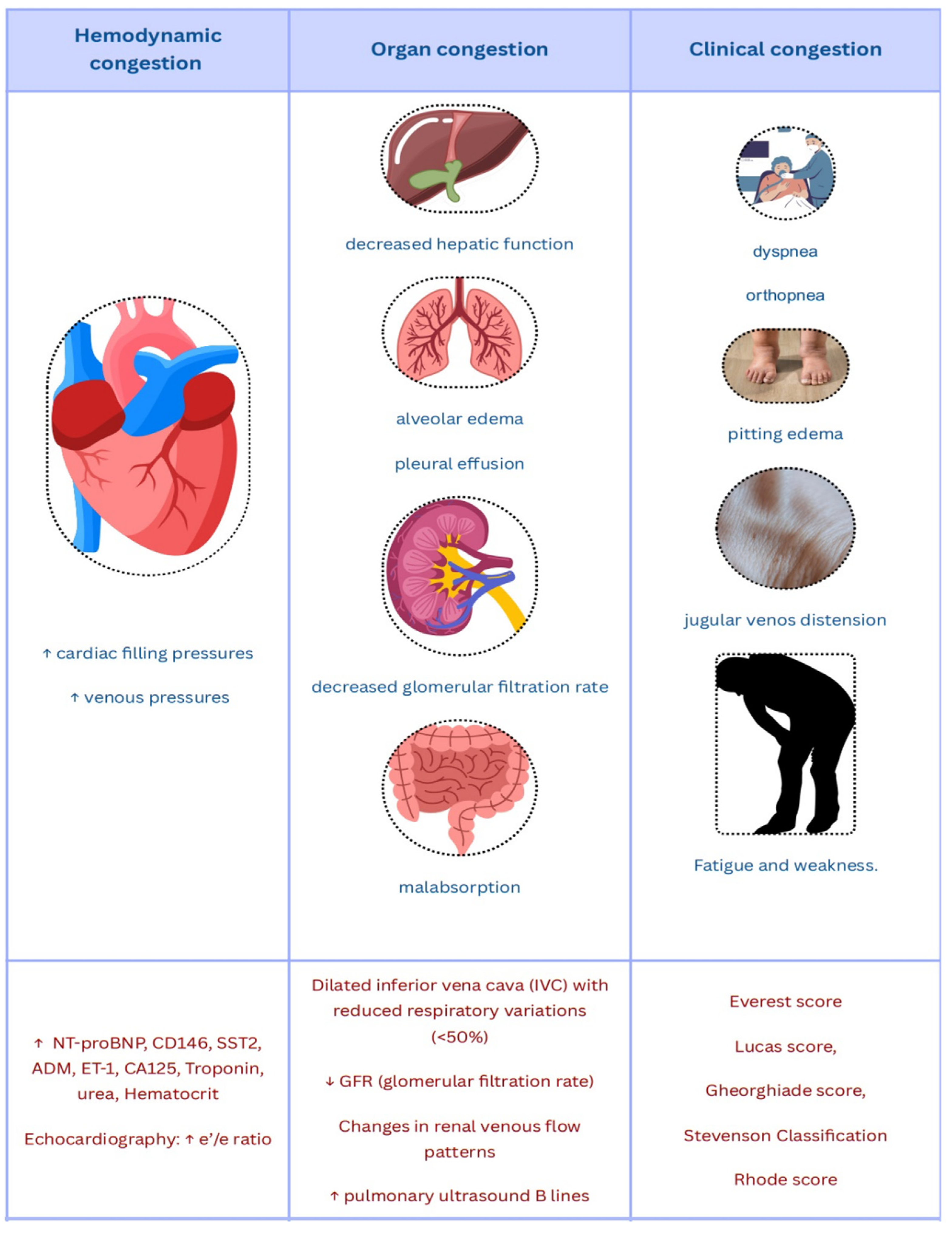

3. Does Congestion Matter in Heart Failure?

4. Does Heart Failure Phenotype Predict Congestion Mechanism?

5. Clinical and Paraclinical Integrative Assessment of Congestion

5.1. Clinical Congestion Scores

5.2. The New Congestion Biomarkers on the Horizon

5.3. Imaging Methods for Assessing Congestion

6. Congestion Management: Diuretics the Sole Remedy for Congestion Relief?

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shahim, B.; Kapelios, C.J.; Savarese, G.; Lund, L.H. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure: An Updated Review. Cardiac Failure Review. 2023, 9, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, B.; Coats, A.J.; Tsutsui, H.; Abdelhamid, M.; Adamopoulos, S.; Albert, N.; et al. Universal Definition and Classification of Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2021, 27, 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.; Mullens, W. How to Tackle Congestion in Acute Heart Failure. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullens, W.; Damman, K.; Harjola, V.; Mebazaa, A.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.; Martens, P.; et al. The Use of Diuretics in Heart Failure with Congestion — a Position Statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girerd, N.; Seronde, M.F.; Coiro, S.; Chouihed, T.; Bilbault, P.; Braun, F.; et al. Integrative Assessment of Congestion in Heart Failure Throughout the Patient Journey. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwinger RHG. Pathophysiology of heart failure. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2021, 11, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijst, P.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Grieten, L.; Dupont, M.; Steels, P.; Tang, W.H.W.; et al. The Pathophysiological Role of Interstitial Sodium in Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudim, M.; Hernandez, A.F.; Felker, G.M. Role of Volume Redistribution in the Congestion of Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourge, R.C.; Abraham, W.T.; Adamson, P.B.; Aaron, M.F.; Aranda, J.M., Jr.; Magalski, A.; et al. COMPASS-HF Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of an implantable continuous hemodynamic monitor in patients with advanced heart failure: the COMPASS-HF study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 51, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, W.T.; Adamson, P.B.; Bourge, R.C.; Aaron, M.F.; Costanzo, M.R.; Stevenson, L.W.; et al. CHAMPION Trial Study Group. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011, 377, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzema, J.; Troughton, R.; Melton, I.; Crozier, I.; Doughty, R.; Krum, H.; et al. Physician- directed patient self-management of left atrial pressure in advanced chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2010, 121, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallick, C.; Sobotka, P.A.; Dunlap, M.E. Sympathetically mediated changes in capacitance: redistribution of the venous reservoir as a cause of decompensation. Circ Heart Fail. 2011, 5, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.L. Fluid Volume Overload and Congestion in Heart Failure: Time to Reconsider Pathophysiology and How Volume Is Assessed. Circ Heart Fail. 2016, 8, e002922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, G.; Metra, M.; Milo-Cotter, O.; Dittrich, H.C.; Gheorghiade, M. Fluid overload in acute heart failure - re-distribution and other mechanisms beyond fluid accumulation. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008, 10, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, P.C.; Onat, D.; Sabbah, H.N. Acute heart failure as “acute endothelitis” - interaction of fluid overload and endothelial dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008, 10, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullens, W.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Nijst, P.; Tang, W.H.W. Renal Sodium Avidity in Heart Failure: From Pathophysiology to Treatment Strategies. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1872–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullens, W.; Abrahams, Z.; Skouri, H.N.; Francis, G.S.; Taylor, D.O.; Starling, R.C.; et al. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure in acute decompensated heart failure: a potential contributor to worsening renal function? J Am Coll Cardiol 2008, 51, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartupee, J.; Mann, D.L. Neurohormonal activation in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017, 14, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, F.; Mattson, D.L.; Skelton, M.M.; Cowley, A.W., Jr. Localization of the vasopressin V1a and V2 receptors within the renal cortical and medullary circulation. Am J Physiol 1997, 273, R243–R251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbrugge, F.H.; Steels, P.; Grieten, L.; Nijst, P.; Tang, W.H.; Mullens, W. Hyponatremia in acute decompensated heart failure: depletion versus dilution. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015, 65, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boorsma, E.M.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Damman, K.; Dinh, W.; Gustafsson, F.; Goldsmith, S.; et al. Congestion in heart failure: a contemporary look at physiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020, 17, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.L.; Cleland, J.G. Causes and treatment of oedema in patients with heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2013, 10, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, J.G.; Dargie, H.J.; Robertson, I.; Robertson, J.I.; East, B.W. Total body electrolyte composition in patients with heart failure: a comparison with normal subjects and patients with untreated hypertension. Br Heart J. 1987, 58, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijst, P.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Grieten, L.; Dupont, M.; Steels, P.; Tang, W.H.W.; et al. The pathophysiological role of interstitial sodium in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015, 65, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titze, J.; Machnik, A. Sodium sensing in the interstitium and relationship to hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010, 19, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heer, M.; Baisch, F.; Kropp, J.; Gerzer, R.; Drummer, C. High dietary sodium chloride consumption may not induce body fluid retention in humans. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000, 278, F585–F595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.J.; Laremore, T.N.; Busch, A.M.; Linhardt, R.J.; Amster, I.J. Influence of charge state and sodium cationization on the electron detachment dissociation and infrared multiphoton dissociation of glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 2008, 19, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, A.H.; Satchell, S.C. Endothelial glycocalyx dysfunction in disease: albuminuria and increased microvascular permeability. J Pathol 2012, 226, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Nijst, P.; Kiefer, K.; Tang, W.H. Endothelial Glycocalyx as Biomarker for Cardiovascular Diseases: Mechanistic and Clinical Implications. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2017, 14, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzelewski, M.; Czarnowska, E.; Beresewicz, A. Superoxide- and nitric oxide-derived species mediate endothelial dysfunction, endothelial glycocalyx disruption, and enhanced neutrophil adhesion in the post-ischemic guinea-pig heart. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005, 56, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schött, U.; Solomon, C.; Fries, D.; Bentzer, P. The endothelial glycocalyx and its disruption, protection and regeneration: a narrative review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016, 24, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, A.H.; Ferguson, J.K.; Burford, J.L.; Gevorgyan, H.; Nakano, D.; Harper, S.J.; et al. Loss of the endothelial glycocalyx links albuminuria and vascular dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012, 23, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusche-Vihrog, K.; Sobczak, K.; Bangel, N.; Wilhelmi, M.; Nechyporuk-Zloy, V.; Schwab, A.; et al. Aldosterone and amiloride alter ENaC abundance in vascular endothelium. Pflugers Arch. 2008, 455, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberleithner, H.; Riethmüller, C.; Schillers, H.; MacGregor, G.A.; de Wardener, H.E.; Hausberg, M. Plasma sodium stiffens vascular endothelium and reduces nitric oxide release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007, 104, 16281–16286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosy, A.P.; Pang, P.S.; Khan, S.; Konstam, M.A.; Fonarow, G.C.; Traver, B.; et al. Clinical Course and Predictive Value of Congestion during Hospitalization in Patients Admitted for Worsening Signs and Symptoms of Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction: Findings from the EVEREST Trial. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegus, J.; Moayedi, Y.; Saldarriaga, C.; Ponikowski, P. Getting ahead of the game: in-hospital initiation of HFrEF therapies. European Heart Journal Supplements. 2022, 24, L38–L44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, P.C.; Jorde, U.P. The active role of venous congestion in the pathophysiology of acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010, 63, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazner, M.H.; Rame, J.E.; Stevenson, L.W.; Dries, D.L. Prognostic Importance of Elevated Jugular Venous Pressure and a Third Heart Sound in Patients with Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zile, M.R.; Bennett, T.D.; St John Sutton, M.; Cho, Y.K.; Adamson, P.B.; Aaron, M.F.; et al. Transition from chronic compensated to acute decompensated heart failure: pathophysiological insights obtained from continuous monitoring of intracardiac pressures. Circulation. 2008, 118, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoroge, J.N.; Teerlink, J.R. Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Approaches to Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Circ Res. 2021, 128, 1468–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, A.; McNulty, S.E.; Mentz, R.J.; Dunlay, S.M.; Vader, J.M.; AbouEzzeddine, O.F.; et al. Relief and Recurrence of Congestion During and After Hospitalization for Acute Heart Failure: Insights From Diuretic Optimization Strategy Evaluation in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (DOSE-AHF) and Cardiorenal Rescue Study in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (CARESS-HF). Circ Heart Fail. 2015, 8, 741–748. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, S.J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Vaduganathan, M.; Khan, S.S.; Butler, J.; Gheorghiade, M. The vulnerable phase after hospitalization for heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015, 12, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, E.; Singh, P.; Collins, S.; Chioncel, O.; Pang, P.; Butler, J. The vulnerable phase of heart failure. Am J Ther. 2018, 25, e456–e464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, E.T.; Jorge, A.J.L.; Rabelo, L.M.; Souza, C.V., Jr. Understanding Hospitalization in Patients with Heart Failure. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Sci. 2017, 30, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiade, M.; Vaduganathan, M.; Fonarow, G.C.; Bonow, R.O. Rehospitalization for heart failure: problems and perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013, 61, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, J.; Barroca, C.; Fernandez, J. A Suggested Model for the Vulnerable Phase of Heart Failure: Assessment of Risk Factors, Multidisciplinary Monitoring, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Addressing the Social Determinants of Health. Cureus. 2023, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, S.J.; Zannad, F.; Fonarow, G.; Subacius, H.P.; Triggiani, M.; Ambrosy, A.P.; et al. In-hospital and Early Post-discharge Troponin Elevations Among Patients Hospitalized for Heart Failure: Insights From the ASTRONAUT Trial. Circulation. 2026. Abstract 12886. [Google Scholar]

- Bistola, V.; Polyzogopoulou, E.; Ikonomidis, I.; Parissis, J. Congestion in acute heart failure with reduced vs. preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: differences, similarities and remaining gaps. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 748–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aelst, L.N.; Arrigo, M.; Placido, R.; Akiyama, E.; Girerd, N.; Zannad, F.; et al. Acutely decompensated heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction present with comparable haemodynamic conges- tion. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdespino-Trejo, A.; Orea-Tejeda, A.; Castillo-Martinez, L.; Keirns-Davis, C.; Montanez-Orozco, A.; Ortiz-Suarez, G.; et al. Low albumin levels and high impedance ratio as risk factors for worsening kidney function during hospitalization of decompensated heart failure patients. Experimental and clinical cardiology. 2013, 18, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Prenner, S.B.; Kumar, A.; Zhao, L.; Cvijic, M.E.; Basso, M.; Spires, T.; et al. Effect of Serum Albumin Levels in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (from the TOPCAT Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2020, 125, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, P.A.; Castelli, W.P.; McNamara, P.M.; Kannel, W.B. The Natural History of Congestive Heart Failure: The Framingham Study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971, 285, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.L.; Pinsky, J.L.; Kannel, W.B.; Levy, D. The Epidemiology of Heart Failure: The Framingham Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1993, 22, A6–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, S.; Guazzi, M.; Scardovi, A.B.; Klersy, C.; Clemenza, F.; Carluccio, E.; et al. Different correlates but similar prognostic implications for right ventricular dysfunction in heart failure patients with reduced or preserved ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Gargani, L.; Palazzuoli, A.; Ambrosio, G.; Bayés-Genis, A.; Lupon, J.; et al. Association between right-sided cardiac function and ultrasound-based pulmonary congestion on acutely decompensated heart failure: findings from a pooled analysis of four cohort studies. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021, 110, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, A.L.; Muccioli, S.; Marazzato, J.; Mancinelli, A.; Iacovoni, A.; De Ponti, R. Prognostic Role of Subclinical Congestion in Heart Failure Outpatients: Focus on Right Ventricular Dysfunction. J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiade, M.; Follath, F.; Ponikowski, P.; Barsuk, J.H.; Blair, J.E.; Cleland, J.G.; et al. European Society of Cardiology; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Assessing and grading congestion in acute heart failure: a scientific statement from the acute heart failure committee of the heart failure association of the European Society of Cardiology and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010, 12, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felker, G.M.; Anstrom, K.J.; Adams, K.F.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Fiuzat, M.; Houston-Miller, N.; et al. Effect of Natriuretic Peptide-Guided Therapy on Hospitalization or Cardiovascular Mortality in High-Risk Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017, 318, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thygesen, K.; Mair, J.; Mueller, C.; Huber, K.; Weber, M.; Plebani, M.; et al.; Study Group on Biomarkers in Cardiology of the ESC Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care Recommendations for the use of natriuretic peptides in acute cardiac care: a position statement from the study group on biomarkers in cardiology of the ESC. Working group on acute cardiac care. Eur Heart J. 2012, 33, 2001–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, C.; McDonald, K.; de Boer, R.A.; Maisel, A.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Kozhuharov, N.; et al. Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiolog practical guidance on the use of natriuretic peptide concentrations. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miñana, G.; de la Espriella, R.; Mollar, A.; Santas, E.; Núñez, E.; Valero, E.; et al. Factors associated with plasma antigen carbohydrate 125 and aminoterminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide concentrations in acute heart failure. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020, 9, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, O.; Tandogan, I.; Yilmaz, M.B.; Gul, I.; Gurlek, A. CA125 Levels among Patients with Advanced Heart Failure: An Emerging Independent Predictor for Survival. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010, 145, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.; de la Espriella, R.; Miñana, G.; Santas, E.; Llácer, P.; Núñez, E.; et al. Antigen carbohydrate 125 as a biomarker in heart failure: a narrative review. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Gracia, J.; Crespo-Aznarez, S.; de la Espriella, R.; Nuñez, G.; Sánchez-Marteles, M.; Garcés-Horna, V.; et al. Utility of plasma CA125 as a proxy of intra-abdominal pressure in patients with acute heart failure. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2022, 11, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, J.; Llàcer, P.; Bertomeu-González, V.; Bosch, M.J.; Merlos, P.; García-Blas, S.; et al.; CHANCE-HF Investigators Carbohydrate antigen-125-guided therapy in acute heart failure: CHANCE-HF: a randomized study. JACC Heart Fail. 2016, 4, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, J.; Llàcer, P.; García-Blas, S.; Bonanad, C.; Ventura, S.; Núñez, J.M.; et al. CA125-guided diuretic treatment versus usual care in patients with acute heart failure and renal dysfunction. Am J Med. 2020, 133, 370–380e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, J.; De La Espriella, R.; Rossignol, P.; Voors, A.A.; Mullens, W.; Metra, M.; et al. Congestion in Heart Failure: A Circulating Biomarker-based Perspective. A Review from the Biomarkers Working Group of the Heart Failure Association, European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 1751–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piek, A.; Du, W.; De Boer, R.A.; Silljé, H.H.W. Novel Heart Failure Biomarkers: Why Do We Fail to Exploit Their Potential? Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2018, 55, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrigo, M.; Truong, Q.A.; Onat, D.; Szymonifka, J.; Gayat, E.; Tolppanen, H.; et al. Soluble CD146 Is a Novel Marker of Systemic Congestion in Heart Failure Patients: An Experimental Mechanistic and Transcardiac Clinical Study. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, N.; Du, X.; Xu, G.; Yan, X. CD146, from a melanoma cell adhesion molecule to a signaling receptor. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020, 5, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, N.; Blot-Chabaud, M.; Despoix, N.; Kebir, A.; Harhouri, K.; Arsanto, J.P.; et al. CD146 and Its Soluble Form Regulate Monocyte Transendothelial Migration. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, J.; Grochowska, M.; Gackowska, L.; Buszko, K.; Bujak, R.; Gilewski, W.; et al. Melanoma cell adhesion molecule as an emerging biomarker with prognostic significance in systolic heart failure. Biomark Med. 2016, 10, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juknevičienė, R.; Simonavičius, J.; Mikalauskas, A.; et al. Soluble CD146 in the detection and grading of intravascular and tissue congestion in patients with acute dyspnoea: analysis of the prospective observational Lithuanian Echocardiography Study of Dyspnoea in Acute Settings (LEDA) cohort. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e061611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikimi, T.; Nakagawa, Y. Adrenomedullin as a biomarker of heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2018, 14, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, D.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Voors, A.A. Bio-adrenomedullin as a potential quick, reliable, and objective marker of congestion in heart failure. Eur JHeart Fail. 2018, 20, 1363–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ter Maaten, J.M.; Kremer, D.; Demissei, B.G.; Struck, J.; Bergmann, A.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Bio-adrenomedullin as a marker of congestion in patients with new-onset and worsening heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandhi, P.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Emmens, J.E.; Struck, J.; Bergmann, A.; Cleland, J.G.; et al. Clinical Value of Pre-discharge Bio-adrenomedullin as a Marker of Residual Congestion and High Risk of Heart Failure Hospital Readmission. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, M.T.; Cameron, V.A.; Charles, C.J.; Lainchbury, J.G.; Nicholls, M.G.; Richards, A.M. Adrenomedullin and Heart Failure. Regul. Pept. 2003, 112, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januzzi, J.L.; Peacock, W.F.; Maisel, A.S.; Chae, C.U.; Jesse, R.L.; Baggish, A.L.; et al. Measurement of the Interleukin Family Member ST2 in Patients with Acute Dyspnea: Results From the PRIDE (Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department) Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 50, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.; Kałużna-Oleksy, M.; Migaj, J.; Sawczak, F.; Krysztofiak, H.; Lesiak, M.; et al. sST2 and Heart Failure-Clinical Utility and Prognosis. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieplinger, B.; Januzzi, J.L.; Steinmair, M.; Gabriel, C.; Poelz, W.; Haltmayer, M.; et al. Analytical and clinical evaluation of a novel high-sensitivity assay for measurement of soluble ST2 in human plasma—The Presage™ ST2 assay. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2009, 409, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Filippi, C.; Daniels, L.B.; Bayes-Genis, A. Structural heart disease and ST2: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 2015, 115, 59B–63B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilinski, J.L.; Shah, R.V.; Gaggin, H.K.; Gantzer, M.L.; Wang, T.J.; Januzzi, J.L. Measurement of multiple biomarkers in advanced stage heart failure patients treated with pulmonary artery catheter guided therapy. Crit Care. 2012, 16, R135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Espriella, R.; Bayés-Genis, A.; Revuelta-López, E.; Miñana, G.; Santas, E.; Llàcer, P.; et al. IMPROVE-HF Investigators. Soluble ST2 and diuretic efficiency in acute heart failure and concomitant renal dysfunction. J Card Fail. 2021, 27, A. [Google Scholar]

- Lotierzo, M.; Dupuy, A.M.; Kalmanovich, E.; Roubille, F.; Cristol, J.P. SST2 as a value-added biomarker in heart failure. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2020, 501, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, L.B.; Maisel, A.S.; Clopton, P.; et al. Association of ST2 levels with cardiac structure and function and mortality in outpatients. Am Heart J. 2010, 160, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannessi, D.; Del Ry, S.; Vitale, R.L. The role of endothelins and their receptors in heart failure. Pharmacol Res. 2001, 43, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendgens, L.; Yagmur, E.; Bruensing, J.; Herbers, U.; Baeck, C.; Trautwein, C.; et al. C-terminal proendothelin-1 (CT-proET-1) is associated with organ failure and predicts mortality in critically ill patients. J Intensive Care. 2017, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obokata, M.; Kane, G.C.; Reddy, Y.N.V.; Melenovsky, V.; Olson, T.P.; Jarolim, P.; et al. The neurohormonal basis of pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2019, 40, 3707–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obokata, M.; Reddy, Y.N.V.; Melenovsky, V.; Sorimachi, H.; Jarolim, P.; Borlaug, B.A. Uncoupling between intravascular and distending pressures leads to underestimation of circulatory congestion in obesity. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieker, L.E.; Noll, G.; Ruschitzka, F.T.; Lüscher, T.F. Endothelin receptor antagonists in congestive heart failure: a new therapeutic principle for the future? Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002, 37, 1493–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezin, A.E. Up-to-Date Clinical Approaches of Biomarkers’ Use in Heart Failure. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2017, 4, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, V.; Aimo, A.; Vergaro, G.; Saccaro, L.; Passino, C.; Emdin, M. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and management of heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2022, 27, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, K.; Monnez, J.M.; Albuisson, E.; Pitt, B.; Zannad, F.; Rossignol, P. Prognostic value of esti- mated plasma volume in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2015, 3, 886–893. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, M.; Girerd, N.; Duarte, K.; Chouihed, T.; Chikamori, T.; Pitt, B.; et al. Estimated plasma volume status in heart failure: clinical implications and future directions. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021, 110, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullens, W.; Damman, K.; Testani, J.M.; Martens, P.; Mueller, C.; Lassus, J.; et al. Evaluation of kidney function throughout the heart failure trajectory - a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miglioranza, M.H.; Picano, E.; Badano, L.P.; Sant’Anna, R.; Rover, M.; Zaffaroni, F.; et al. Pulmonary congestion evaluated by lung ultrasound predicts decompensation in heart failure outpatients. Int J Cardiol. 2017, 240, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiro, S.; Rossignol, P.; Ambrosio, G.; Carluccio, E.; Alunni, G.; Murrone, A.; et al. Prognostic value of residual pulmonary congestion at discharge assessed by lung ultrasound imaging in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 1172–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobs, A.; Brünjes, K.; Katalinic, A.; Babaev, V.; Desch, S.; Reppel, M.; et al. Inferior vena cava diameter in acute decompensated heart failure as predictor of all-cause mortality. Heart Vessels. 2017, 32, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandwalla, R.M.; Birkeland, K.T.; Zimmer, R.; Henry, T.D.; Nazarian, R.; Sudan, M.; et al. Usefulness of Serial Measurements of Inferior Vena Cava Diameter by VscanTM to Identify Patients With Heart Failure at High Risk of Hospitalization. Am J Cardiol. 2017, 119, 1631–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicori, P.; Platz, E.; Dauw, J.; Martens, P.; Pivetta, E.; Cleland, G.F.; McMurray, J.V.; et al. Ultrasound imaging of congestion in heart failure: Examinations beyond the heart. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2021, 33, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijst, P.; Martens, P.; Dupont, M.; Tang, W.H.; Mullens, W. Intrarenal flow alterations during transition from euvolemia to intravascular volume expansion in heart failure patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2017, 5, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojcevski, B.; Celic, V.; Navarin, S.; Pencic, B.; Majstorovic, A.; Sljivic, A.; et al. The use of discharge haemoglobin and NT-proBNP to improve short and long-term outcome prediction in patients with acute heart failure. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2017, 6, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, M.R.; Negoianu, D.; Jaski, B.E.; Bart, B.A.; Heywood, J.T.; Anand, I.S.; et al. Aquapheresis versus intravenous diuretics and hospitalizations for heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2016, 4, 95105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, D.H. Diuretic therapy and resistance in congestive heart failure. Cardiology. 2001, 96, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, P.; Nijst, P.; Mullens, W. Current approach to decongestive therapy in acute heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2015, 12, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loncar, G.; Springer, J.; Anker, M.; Doehner, W.; Lainscak, M. Cardiac cachexia: hic et nunc: “hic et nunc” - here and now. Int J Cardiol. 2015, 201, e1–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanberg, J.S.; Rao, V.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Laur, O.; Brisco, M.A.; Perry Wilson, F.; et al. Hypochloremia and Diuretic Resistance in Heart Failure: Mechanistic Insights. Circ Heart Fail. 2016, 9, 003180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, A.L.; Braveman, W.S. Treatment of the Low-Salt Syndrome in Congestive Heart Failure by the Controlled Use of Mercurial Diuretics. Circulation. 1956, 13, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfar, A.; Sambandam, K.K. The Basic Metabolic Profile in Heart Failure-Marker and Modifier. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2017, 14, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, V.S.; Andrade, L.; Ayub-Ferreira, S.M.; Bacal, F.; de Bragança, A.C.; Guimarães, G.V.; et al. Hypertonic saline solution for prevention of renal dysfunction in patients with decompensated heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013, 167, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmeier, R.S.; Le, T.T.; Kamalay, S.E.; Utecht, K.N.; Nikstad, T.P.; Kaliebe, J.W.; et al. Randomized Trial of High Dose Furosemide-Hypertonic Saline in Acute decompensated heart failure with advanced heart failure with renal disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012, 59, E958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liszkowski, M.; Nohria, A. Rubbing salt into wounds: hypertonic saline to assist with volume removal in heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2010, 7, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullens, W.; Abrahams, Z.; Francis, G.S.; Skouri, H.N.; Starling, R.C.; Young, J.B.; et al. Sodium nitroprusside for advanced low-output heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 52, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebazaa, A.; Davison, B.; Chioncel, O.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Diaz, R.; Filippatos, G.; et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapies for acute heart failure (STRONG-HF): a multinational, open-label, randomised, trial. Lancet. 2022, 400, 1938–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knauf, H.; Mutschler, E. Pharmacodynamic and kinetic considerations on diuretics as a basis for differential therapy. Klin Wochenschr. 1991, 69, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, M.V.; Grossmann, S.; Roesinger, M.; Gresko, N.; Todkar, A.P.; Barmettler, G.; et al. Rapid dephosphorylation of the renal sodium chloride cotransporter in response to oral potassium intake in mice. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brisco-Bacik, M.A.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Houser, S.R.; Vedage, N.A.; Rao, V.; Ahmad, T.; et al. Outcomes Associated With a Strategy of Adjuvant Metolazone or High-Dose Loop Diuretics in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Propensity Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e009149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J.; Anstrom, K.J.; Felker, G.M.; Givertz, M.M.; Kalogeropoulos, A.P.; Konstam, M.A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of spironolactone in acute heart failure: the ATHENA-HF randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbrugge, F.H.; Martens, P.; Ameloot, K.; Haemels, V.; Penders, J.; Dupont, M.; et al. Spironolactone to increase natriuresis in congestive heart failure with cardiorenal syndrome. Acta Cardiol. 2019, 74, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullens, W.; Dauw, J.; Martens, P.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Nijst, P.; Meekers, E.; et al. ADVOR Study Group. Acetazolamide in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure with Volume Overload. N Engl J Med. 2022, 387, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, H.; Packer, M. Acetazolamide for acute heart failure: is ADVOR a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma? Eur Heart J. 2023, 44, 3683–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.J.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kober, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019, 381, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; et al. EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Investigators. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Amin, N.; Sabir, F.; Amin, T.; Sarfraz, Z.; Sarfraz, A.; Robles-Velasco, K.; et al. SGLT2 Inhibitors in Acute Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Healthcare (Basel). 2022, 10, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voors, A.A.; Angermann, C.E.; Teerlink, J.R.; Collins, S.P.; Kosiborod, M.; Biegus, J.; et al. The SGLT2 Inhibitor Empagliflozin in Patients Hospitalized for Acute Heart Failure: A Multinational Randomized Trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, Z. ‘DICTATE-AHF: Early Dapagliflozin Initiation in Acute Heart Failure, European Society of Cardiology Congress. Amsterdam, Netherlands, 28 August 202. 20 August.

- Schulze, P.C.; Bogoviku, J.; Westphal, J.; Aftanski, P.; Haertel, F.; Grund, S.; et al. Effects of Early Empagliflozin Initiation on Diuresis and Kidney Function in Patients With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (EMPAG-HF). Circulation. 2022, 146, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G.; Sattar, N.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Lund, L.H.; Fitchett, D.; et al. Empagliflozin Is Associated with a Lower Risk of Post-Acute Heart Failure Rehospitalization and Mortality: Insights from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME Trial. Circulation. 2019, 139, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).