Submitted:

28 January 2024

Posted:

30 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

Optimization of experimental conditions

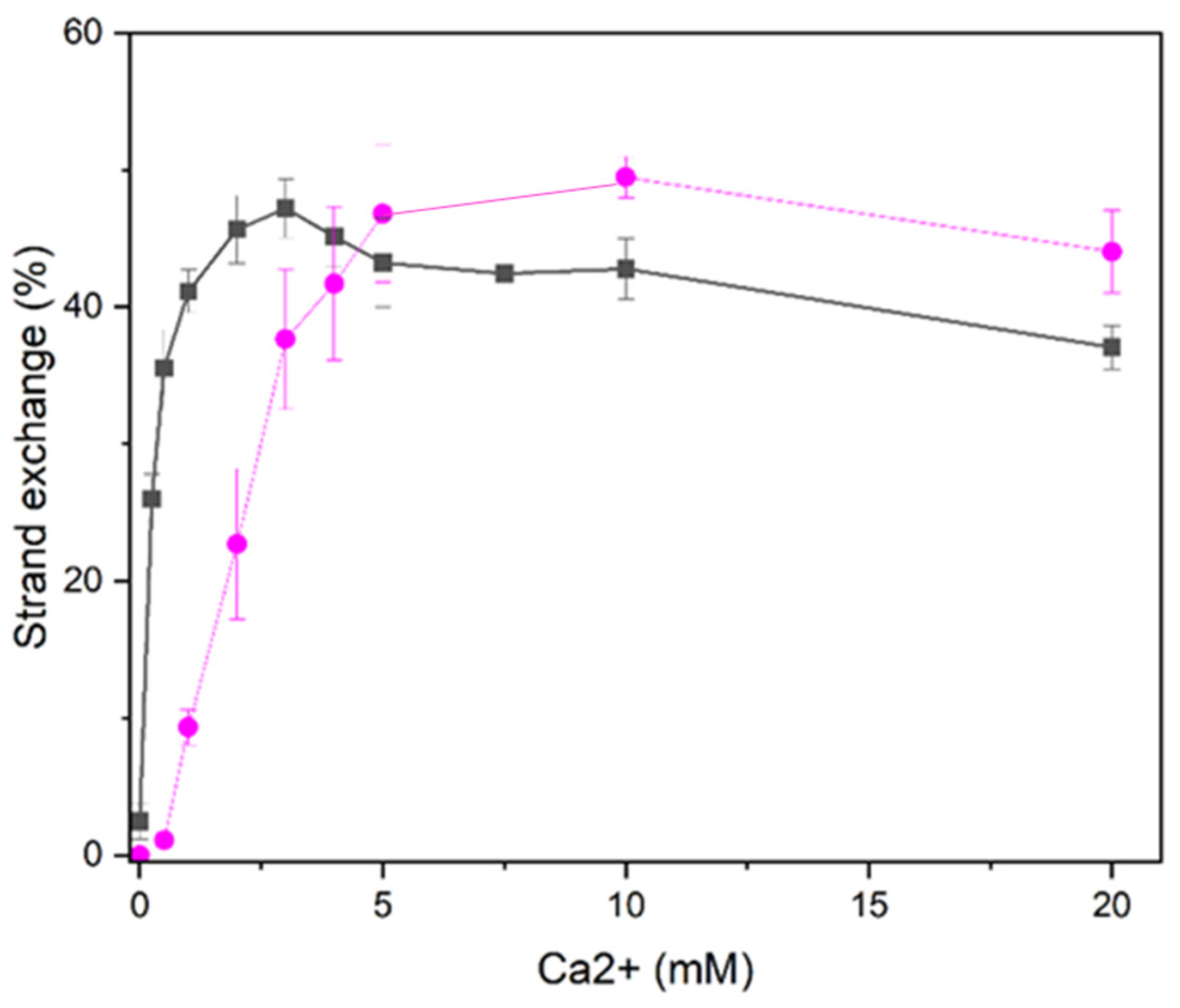

Higher Ca2+ concentration required for D-loop formation than oligonucleotide strand exchange

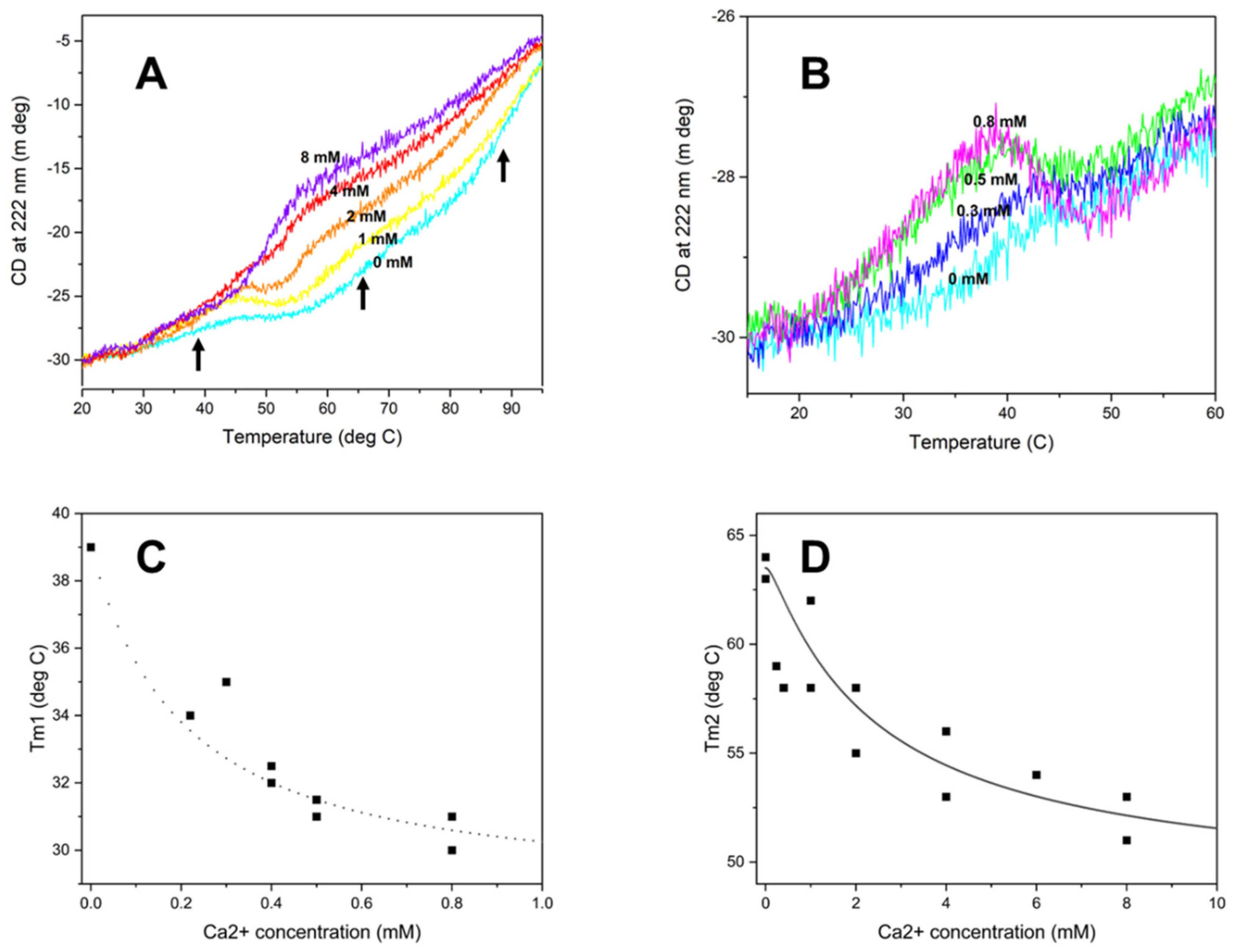

HsRad51 binds more than two Ca2+ ions: thermal denaturation measurements

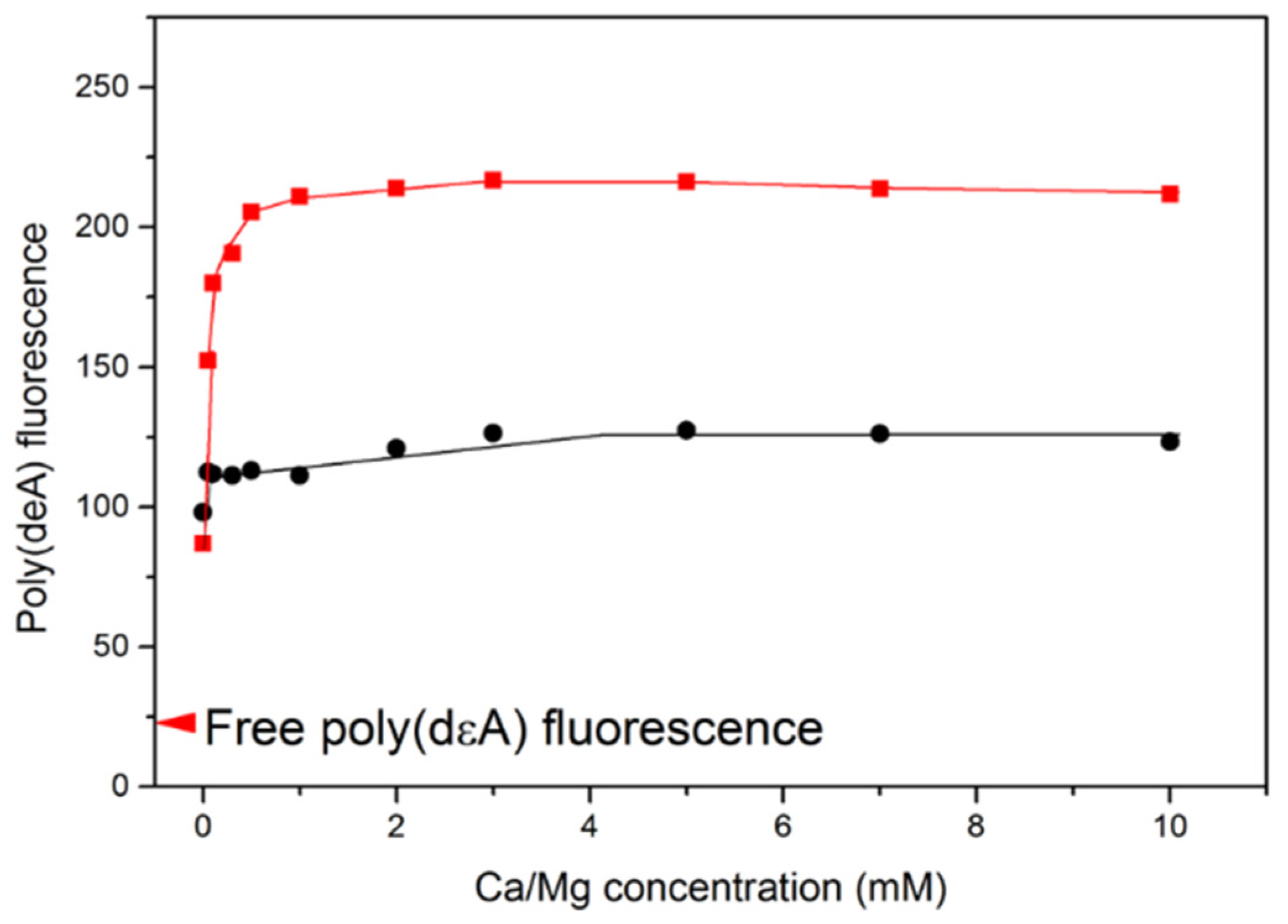

Saturation of poly(dεA) fluorescence change requires less than 1 mM Ca2

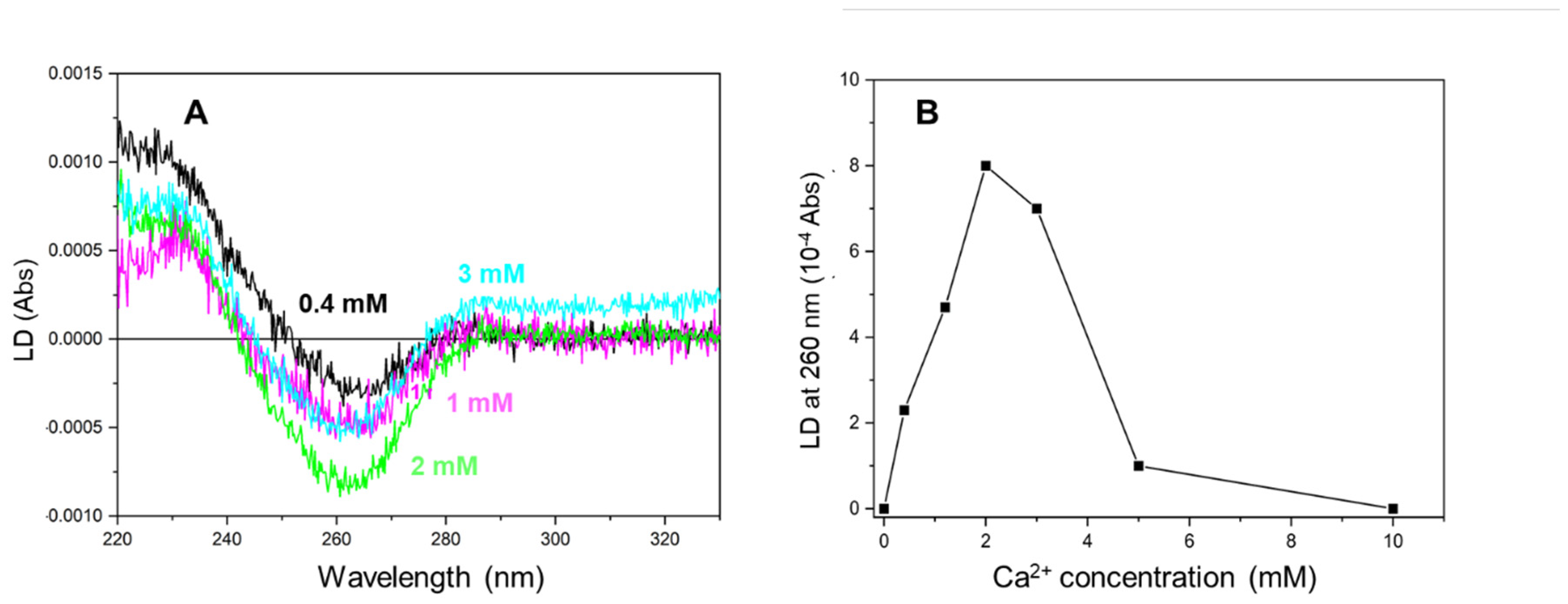

More than 2 mM of Ca2+ was required to saturate the LD signal

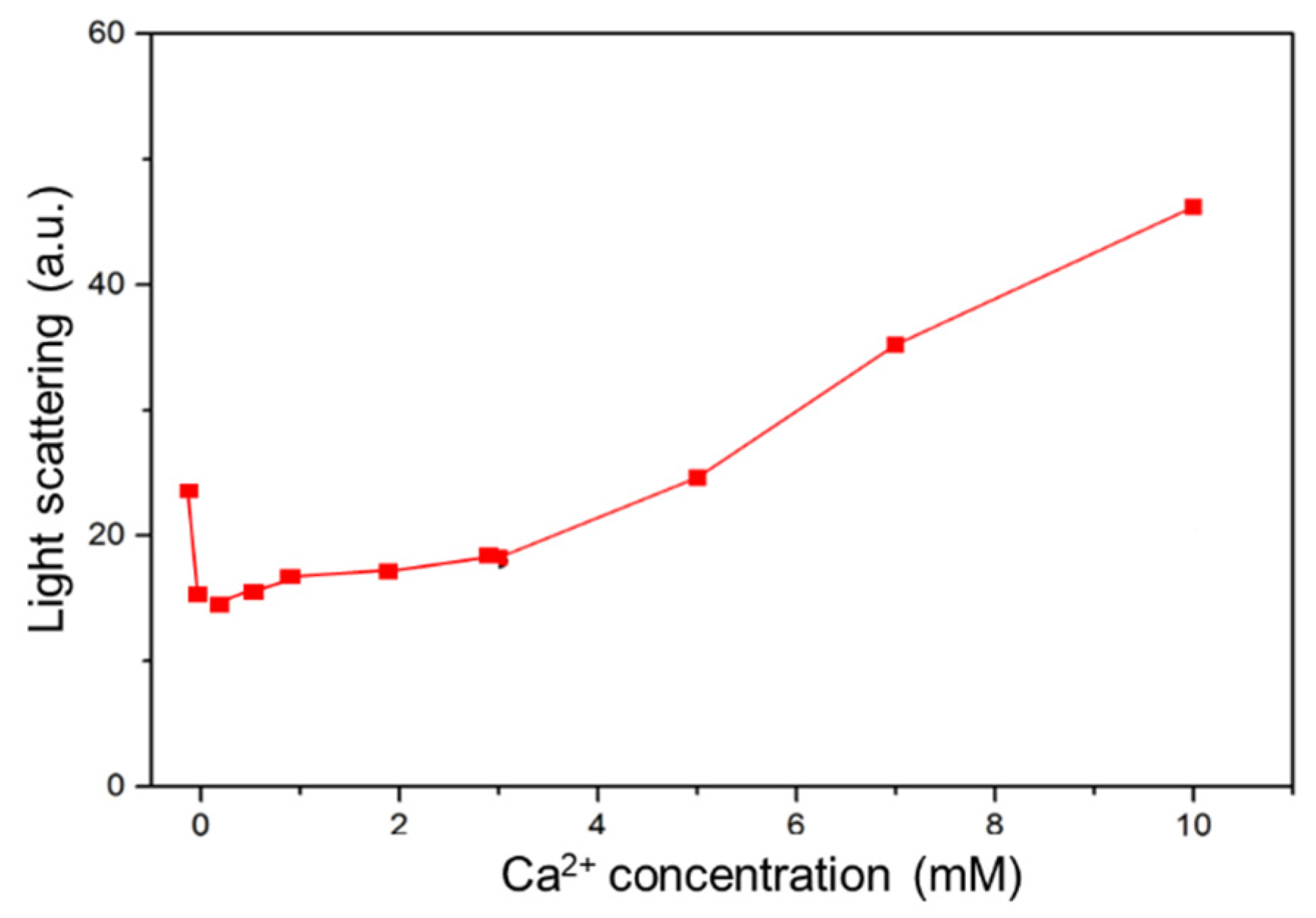

Light scattering promoted at high Ca2+ concentrations

DISCUSSION

Similarity with the activation of strand exchange by Swi5-Sfr1 protein

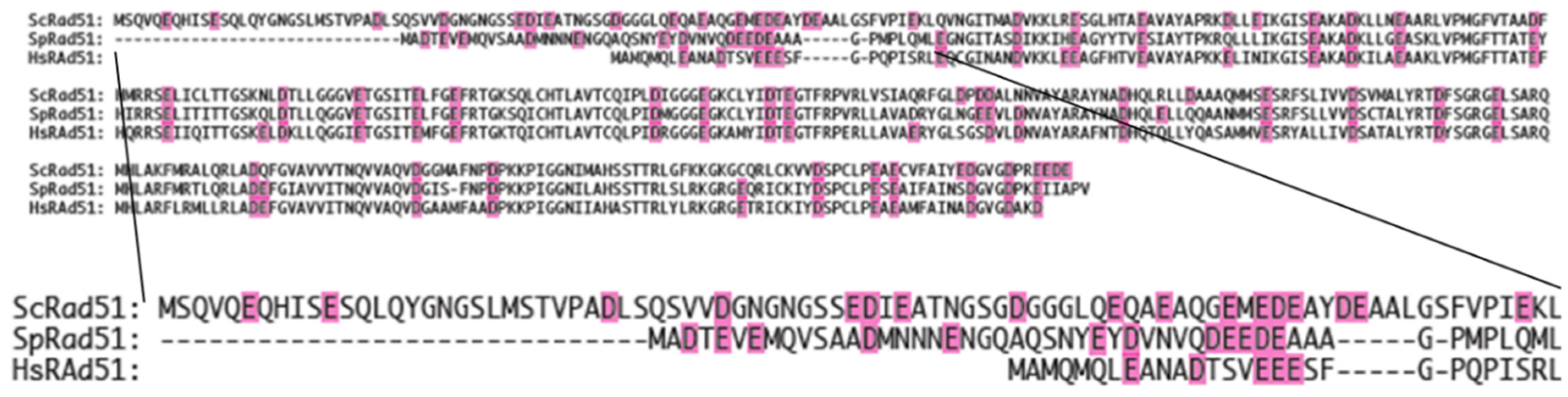

Potential Ca2+-binding site at the N-terminal extremity of HsRad51

Similarity with the activation of RecA-promoted strand exchange by Mg2+

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Experimental conditions

LD measurements

CD measurements of thermal unfolding

Fluorescence measurements

Strand exchange and D-loop formation

Author Contributions

References

- Shinohara, A.; Ogawa, H.; Matsuda, Y.; et al. Cloning of human, mouse and fission yeast recombination genes homologous to RAD51 and recA. Nat Genet, 1993, 4, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, P.; West, S.C. Role of the human RAD51 protein in homologous recombination and double-stranded-break repair. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998, 23, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, R.; Beach, A.; Li, K.; Haber, J. Rad51-mediated double-strand break repair and mismatch correction of divergent substrates. Nature, 2017, 544, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerton, J.; Hawley, R. Homologous chromosome interactions in meiosis: diversity amidst conservation. Nat Rev Genet, 2005, 6, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- suzuki, T.; Fujii, Y.; Sakumi, K.; Tominaga, Y.; Nakao, K.; Sekiguchi, M.; Matsushiro, A.; Yoshimura, Y.; Morita, T. Targeted disruption of the Rad51 gene leads to lethality in embryonic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996, 93, 6236–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindra, R.S.; Schaffer, P.J.; Meng, A.; Woo, J.; Måseide, K.; Roth, M.E.; Lizardi, P.; Hedley, D.W.; Bristow, R.G.; Glazer, P.M. Down-regulation of Rad51 and decreased homologous recombination in hypoxic cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 8504–8518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, A.J.R.; Schiestl, R.H. Homologous recombination and its role in carcinogenesis. J. Biomed. Biotech. 2002, 2, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeke, A.L.; Pishvaian, M.J.; Lynce, F.; Xiu, J.; Brody, J.R.; Chen, W.J.; Baker, T.M.; Marshall, J.L.; Isaacs, C. Prevalence of homologous recombination related gene mutations across multiple cancer types. JCO Precision Oncology 2018, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Jia, R.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q.; Hu, X.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Ren, Y. The Emerging Roles of Rad51 in Cancer and Its Potential as a Therapeutic Target. Front Oncol. 2022, 935593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P. Function of yeast Rad52 protein as a mediator between replication protein A and the Rad51 recombinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 28194–28197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P. Yeast Rad55 and Rad57 proteins form a heterodimer that functions with replication protein A to promote DNA strand exchange by Rad51 recombinase. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P.; Krejci, L.; Van Komen, S.; Sehorn, M.G. Rad51 recombinase and recombination mediators. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 42729–42732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.B.; Carreira, A.; Kowalczykowski, S.C. Purified human BRCA2 stimulates RAD51-mediated recombination. Nature 2010, 467, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, Y.; Dziadkowiec, D.; Ikeguchi, M.; Shinagawa, H.; Iwasaki, H. Two different Swi5-containing protein complexes are involved in mating-type switching and recombination repair in fission yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2003, 100, 15770–15775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akamatsu, Y.; et al. Fission yeast Swi5/Sfr1 and Rhp55/Rhp57 differentially regulate Rhp51-dependent recombination outcomes. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haruta, N.; et al. The Swi5-Sfr1 complex stimulates Rhp51/Rad51- and Dmc1-mediated DNA strand exchange in vitro. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006, 13, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Murayama, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Iwasaki, H. Two three-strand intermediates are processed during Rad51-driven DNA strand exchange. Nature Struct. & Mol. Biol. 2018, 25, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bugreev, D.V.; Mazin, A.V. Ca2+ activates human homologous recombination protein Rad51 by modulating its ATPase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 9988–9993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.; Weterings, E.; Mahadevan, D.; Sanan, A.; Weinand, M.; Stea, B.; et al. Expression levels of RAD51 inversely correlate with survival of glioblastoma patients. Cancers, 2021, 13, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.B.; Wu, Y.L.; Yang, X.N.; Zhong, W.Z.; Xie, D.; Guan, X.Y.; et al. High-Level expression of Rad51 is an independent prognostic marker of survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Br J Cancer, 2005, 93, 137–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, H. O.; Brend, T.; Payne, H. L.; Wright, A.; Ward, T. A.; Patel, K.; Egnuni, T.; Stead, L. F.; Patel, A.; Wurdak, H.; Short, S. C. RAD51 is a selective DNA repair target to radiosensitize glioma stem cells. Stem Cell Reports, 2016, 8, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachechiladze, M.; Škarda, J.; Soltermann, A.; Joerger, M. RAD51 as a potential surrogate marker for DNA repair capacity in solid malignancies. International Journal of Cancer, 2017, 141, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orhan, E.; Velazquez, C.; Tabet, I.; Sardet, C.; Theillet, C. Regulation of RAD51 at the transcriptional and functional levels: What prospects for cancer therapy? Cancers (Basel), 2021, 13, 2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taki, T.; Ohnishi, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Hiraga, S.; Arita, N.; Izumoto, S.; Hayakawa, T.; Morita, T. Antisense inhibition of the RAD51 enhances radiosensitivity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 1996, 223, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, A.; Khanna, K.K.; Wiegmans, A.P. Targeting homologous recombination, new pre-clinical and clinical therapeutic combinations inhibiting RAD51. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 2014, 41, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, M.K.; Buckanovich, R. J.; Bernstein, K. A. Regulation and pharmacological targeting of RAD51 in cancer. NAR Cancer, 2020, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeyer, A.; Benhelli-Mokrani, H.; Chénais, B.; Weigel, P.; Fleury, F. Inhibiting homologous recombination by targeting RAD51 protein. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021, 1876, 188597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Murayama, Y.; Kurokawa, Y.; Kanamaru, S.; Kokabu, Y.; Maki, T.; Mikawa, T.; Argunhan, B.; Tsubouchi, H.; Ikeguchi, M.; Takahashi, M.; Iwasaki, H. Real-time tracking reveals catalytic roles for the two DNA binding sites of Rad51. Nature Communications, 2020, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornander, L.H.; Renodon-Corniere, A.; Kuwabara, N.; Ito, K.; Tsutsui, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Iwasaki, H.; Norden, B.; Takahashi, M. Swi5-Sfr1 protein stimulates Rad51-mediated DNA strand exchange reaction through organization of DNA bases in the presynaptic filament. Nucl. Acids Res. 2014, 42, 2358–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornander, L.H.; Frykholm, K.; Reymer, A.; Renodon-Cornière, A.; Takahashi, M.; Nordén, B. Ca2+ improves organization of single-stranded DNA bases in human Rad51 filament, explaining stimulatory effect on gene recombination. Nucl. Acids Res. 2012, 40, 4904–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazemore, L.R.; Takahashi, M.; Radding, C.M. Kinetic analysis of pairing and strand exchange catalyzed by RecA: Detection by fluorescence energy transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 14672–14682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, B.M.; Vanderkooi, J.; Kallenbach, N.R. Base stacking in a fluorescent dinucleoside monophosphate: εApεA. Biopolymers 1978, 17, 1361–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabbert, M.; Lami, H.; Takahashi, M. Cofactor-induced orientation of the DNA bases in single-stranded DNA complexed with RecA protein. A fluorescence anisotropy and time-decay study. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 5395–5400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, M.; Norden, B. Linear dichroism measurements for the study of protein-DNA interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minton, A.P. Recent applications of light scattering measurement in the biological and biopharmaceutical sciences. Anal. Biochem. 2016, 501, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.M. Static and dynamic light scattering of biological macromolecules: what can we learn? Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 1997, 8, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Kanamaru, S.; Mikawa, T.; Prevost, C.; Ishii, K.; Ito, K.; Uchiyama, S.; Oda, M.; Iwasaki, H.; Kim, S.K.; Takahashi, M. RecA requires two molecules of Mg2+ ions for its optimal strand exchange activity in vitro. Nucl. Acids Res, 2018, 46, 2548–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusetti, S.L.; Shaw, J.J.; Cox, M.M. Magnesium ion-dependent activation of the RecA protein involves the C terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 16381–16388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.F.; Su, S. The regulation mechanism of the C-terminus of RecA proteins during DNA strand-exchange process. Biophys J. 2021, 120, 3166–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E. Wilson, Arnold Chin, Chelation of divalent cations by ATP, studied by titration calorimetry. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 193, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolay Korolev, Alexander P. Lyubartsev, Allan Rupprecht, and Lars Nordenskiöld, L. Competitive binding of Mg2+, Ca2+, Na+, and K+ ions to DNA in oriented DNA fibers: Experimental and Monte Carlo simulation results. Biophys. J. 1999, 77, 2736–2749. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celej, M.S.; Montich, G.G.; Fidelio, G.D. Protein stability induced by ligand binding correlates with changes in protein flexibility. Protein Science, 2003, 12, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, N.J. Using circular dichroism spectra to estimate protein secondary structure. Nat Protoc. 2006, 1, 2876–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, A.; Lynch, T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Crystal structure of a Rad51 filament. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2004, 11, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, L.; et al. Insights into DNA recombination from the structure of a Rad51-BRCA2 complex. Nature 2002, 420, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinograd, J.; Lebowitz, J.; Watson, R. Early and late helix-coil transitions in closed circular DNA the number of superhelical turns in polyoma DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1968, 33, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugaya, N.; Tanaka, S.; Keyamura, K.; Noda, S.; Akanuma, G.; Hishida, T. N-terminal acetyltransferase NatB regulates Rad51-dependent repair of double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Genet Syst. 2023, 98, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yata, K.; Lloyd, J.; Maslen, S.; Bleuyard, J.Y.; Skehel, M.; Smerdon, S.J.; Esashi, F. Plk1 and CK2 act in concert to regulate Rad51 during DNA double strand break repair. Molecular cell. 2012, 45, 371–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimonkar, A.V.; Dombrowski, C.C.; Siino, J.S.; Stasiak, A.Z.; Stasiak, A.; Kowalczykowski, S.C. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dmc1 and Rad51 proteins preferentially function with Tid1 and Rad54 proteins, respectively, to promote DNA strand invasion during genetic recombination. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 28727–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, Y.; Sakane, I.; Takizawa, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Kurumizaka, H. Roles of the human Rad51 L1 and L2 loops in DNA binding. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 3148–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazenave, C.; Toulme, J.J.; Hélène, C. Binding of RecA protein to single-stranded nucleic acids: spectroscopic studies using fluorescent polynucleotides. EMBO J. 1983, 2, 2247–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledneva, R.K.; Razjivin, A.P.; Kost, A.A.; Bogdanov, A.A. Interaction of tobacco mosaic virus protein with synthetic polynucleotides containing a fluorescent label: optical properties of poly(A,epsilonA) and poly(C,epsilonC) copolymers and energy migration from the tryptophan to 1,N6-ethenoadenine or 3,N4-ethenocytosine residues in RNP. Nucleic. Acids Res. 1978, 5, 4225–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).