Submitted:

14 December 2023

Posted:

29 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

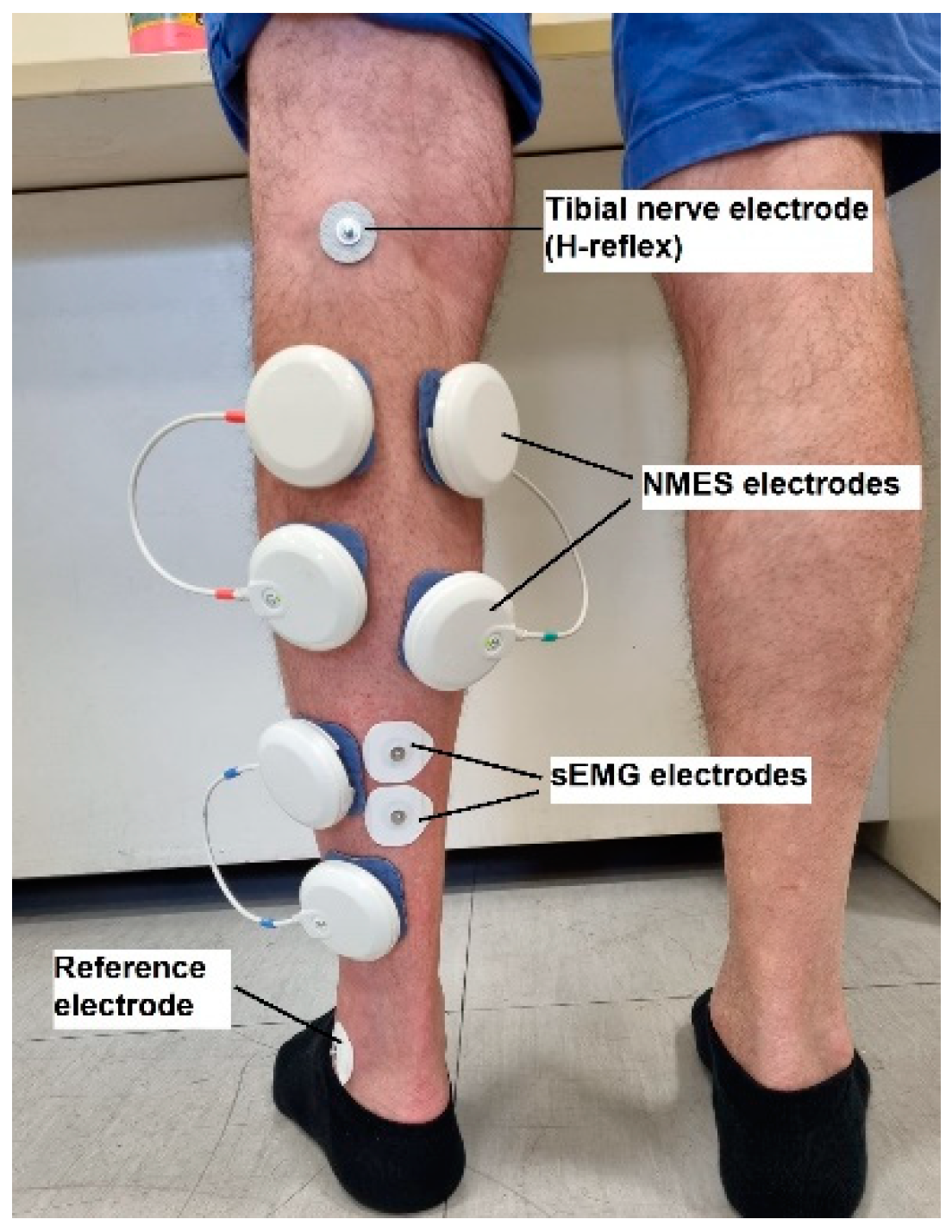

2.2. Instrumentation

2.2.1. Maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC)

2.2.2. Surface electromyography (sEMG)

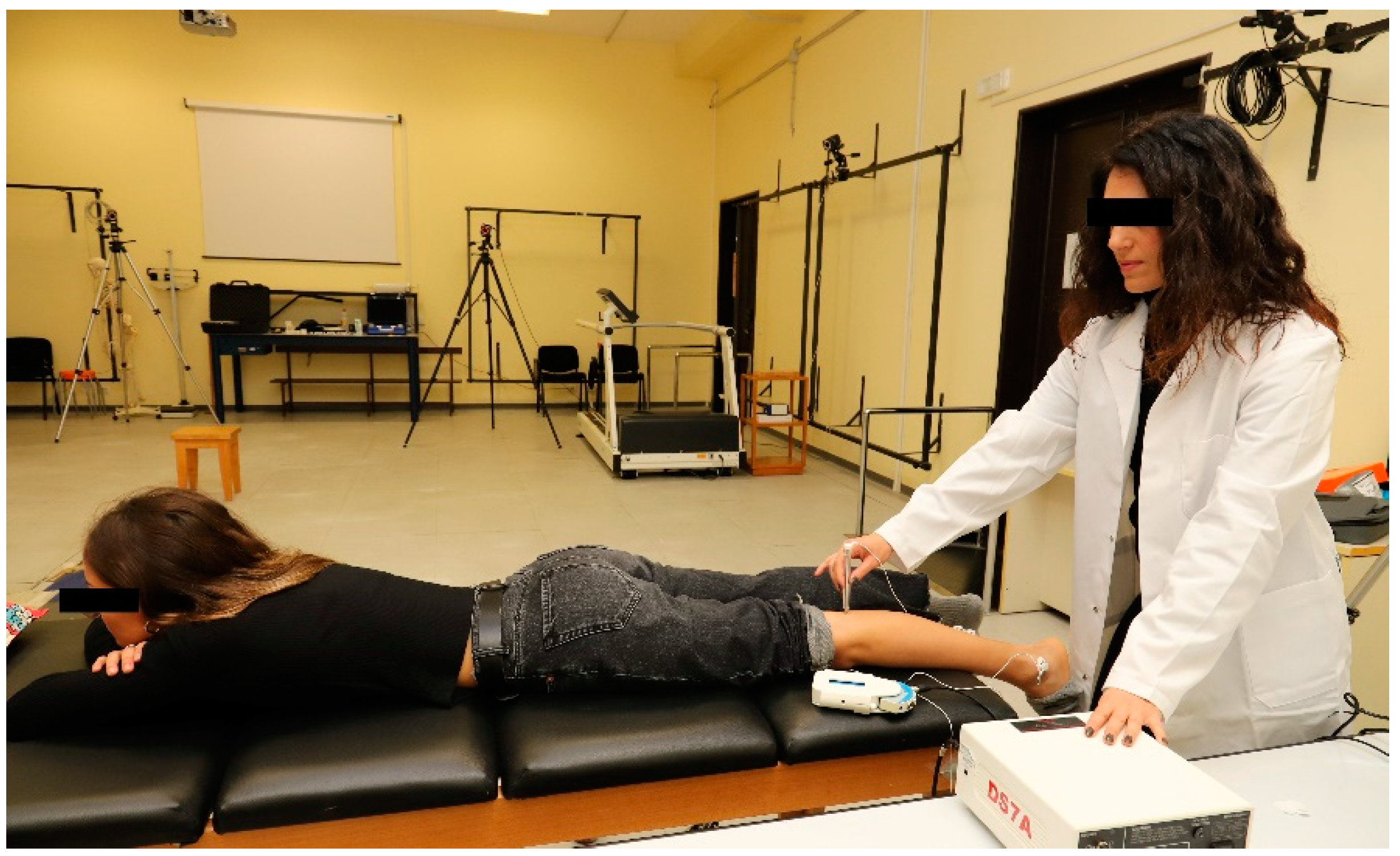

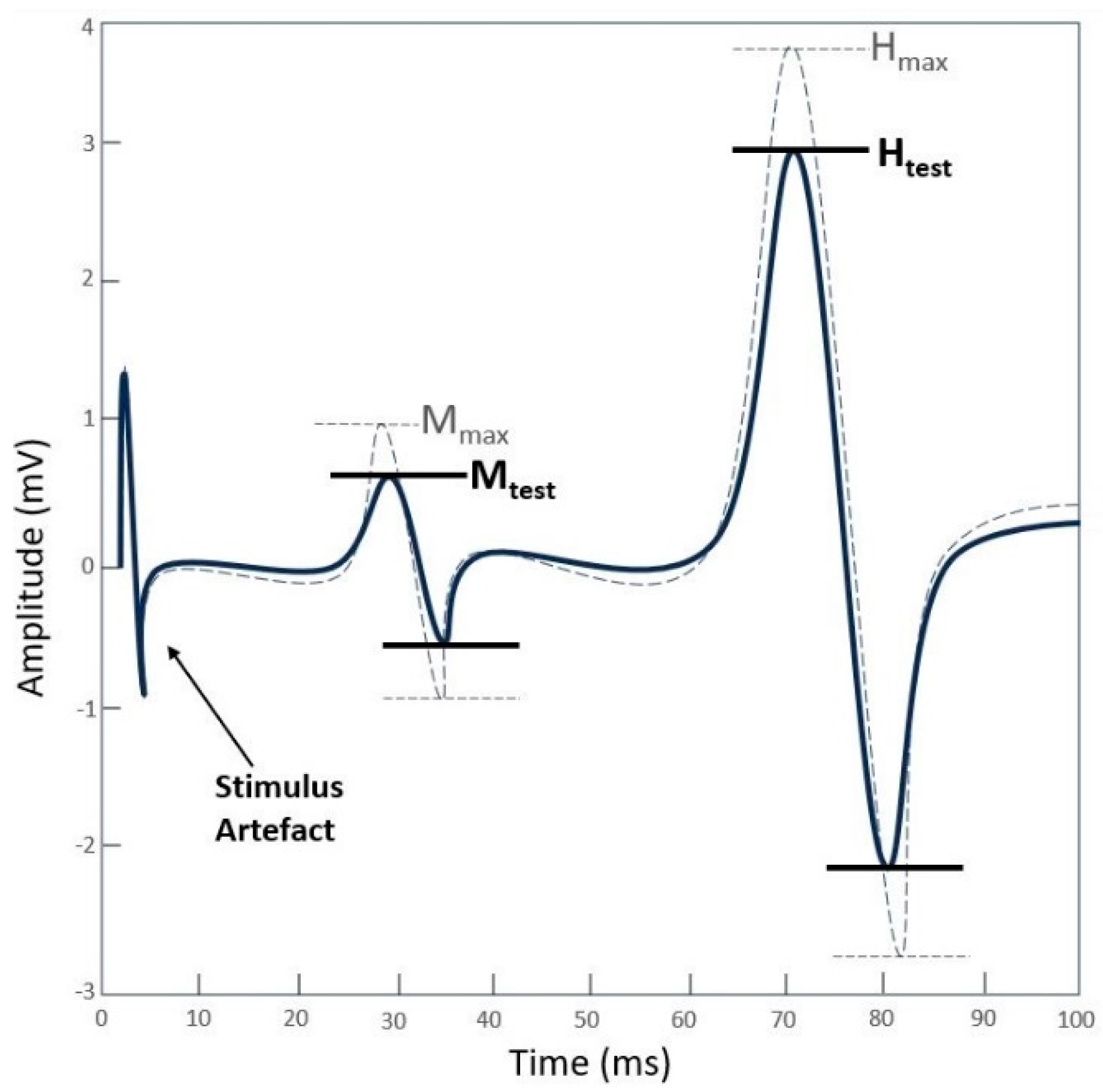

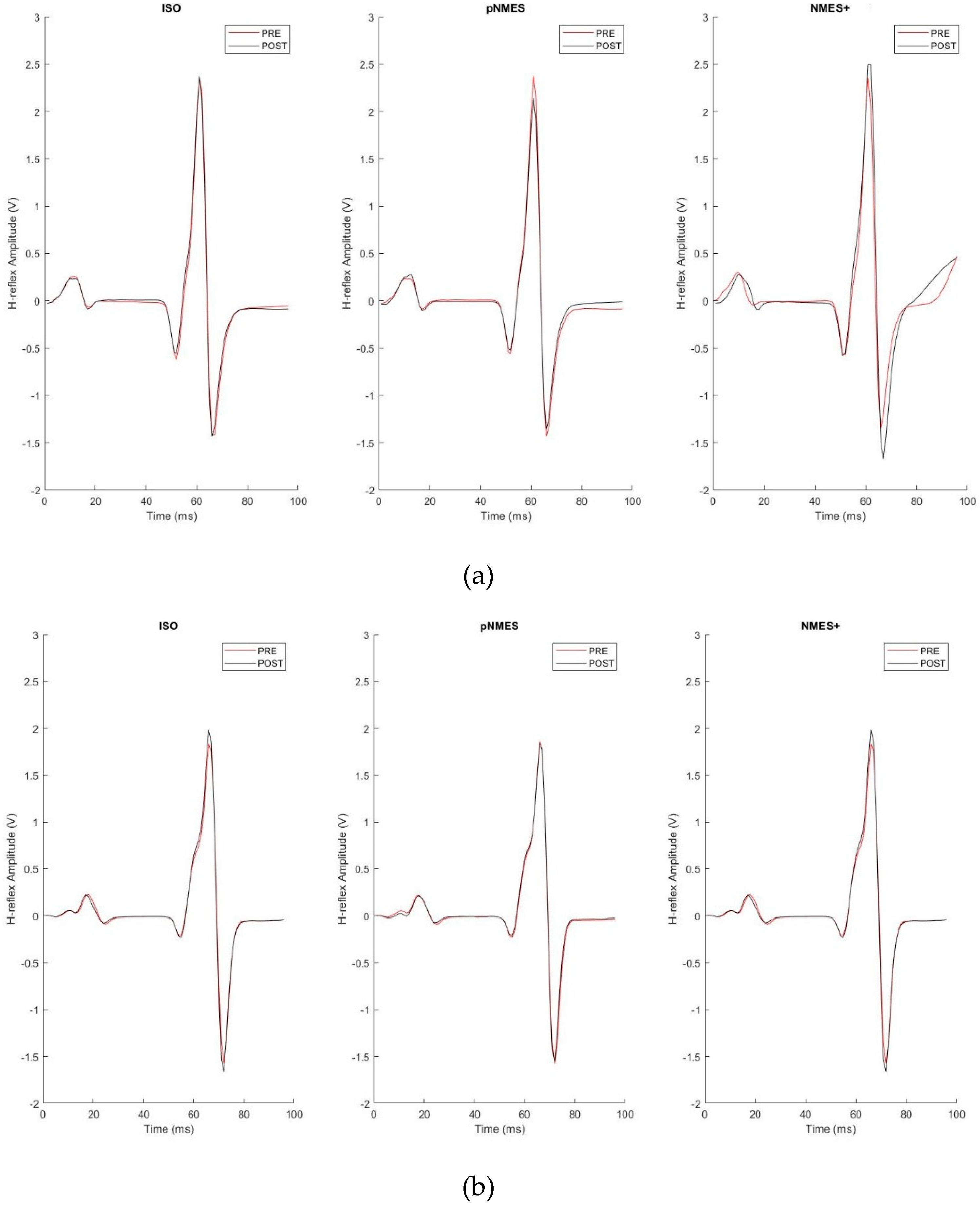

2.2.3. Soleus H-reflex

2.2.4. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES)

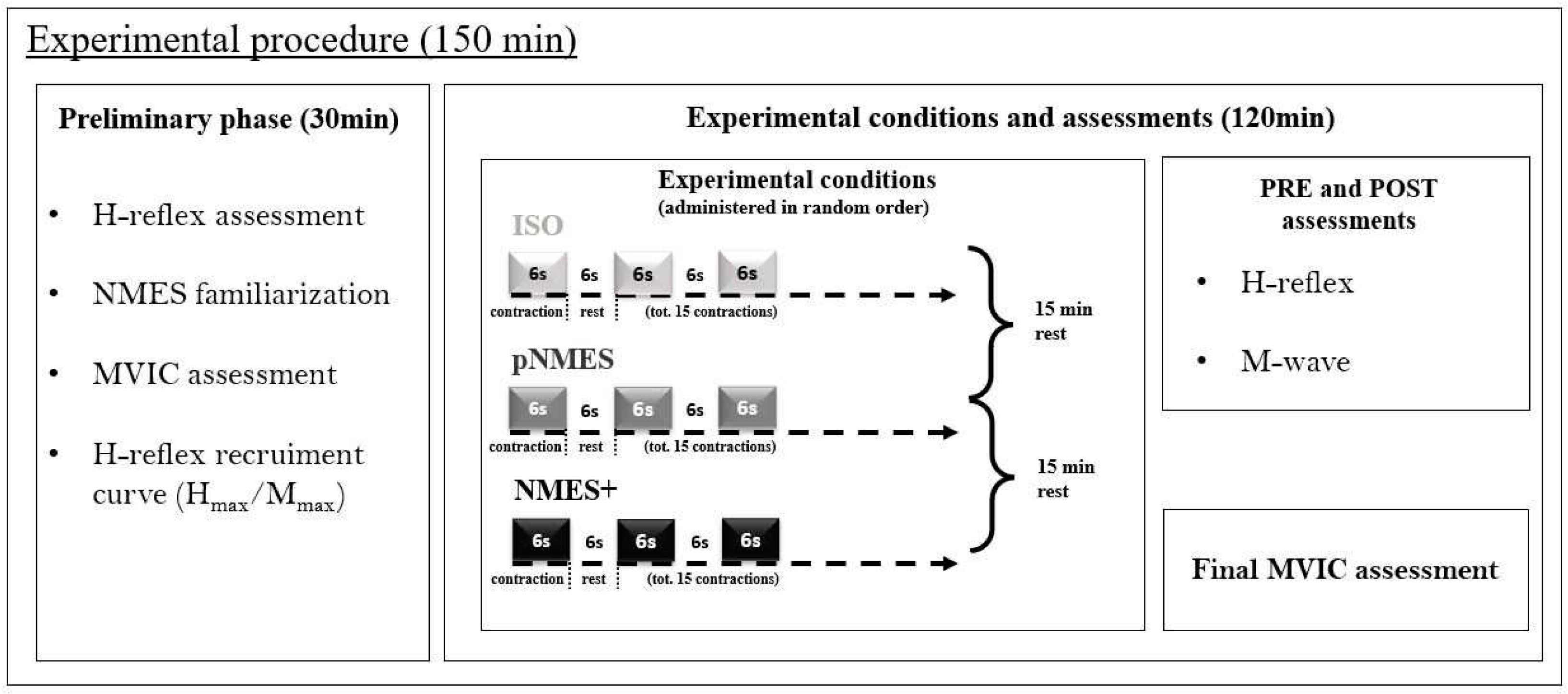

2.3. Experimental procedure

2.4. Data analysis

2.5. Statistical analysis

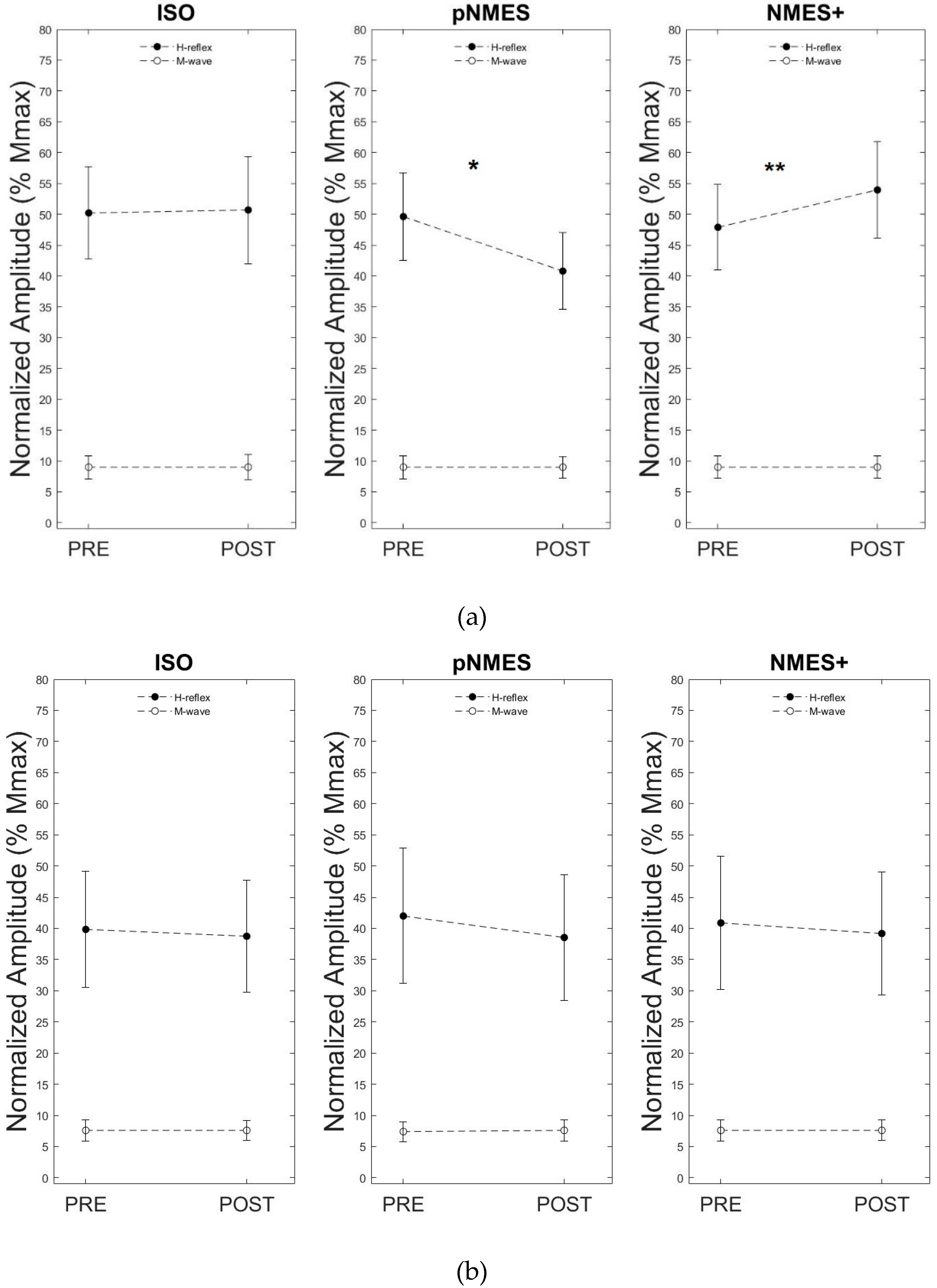

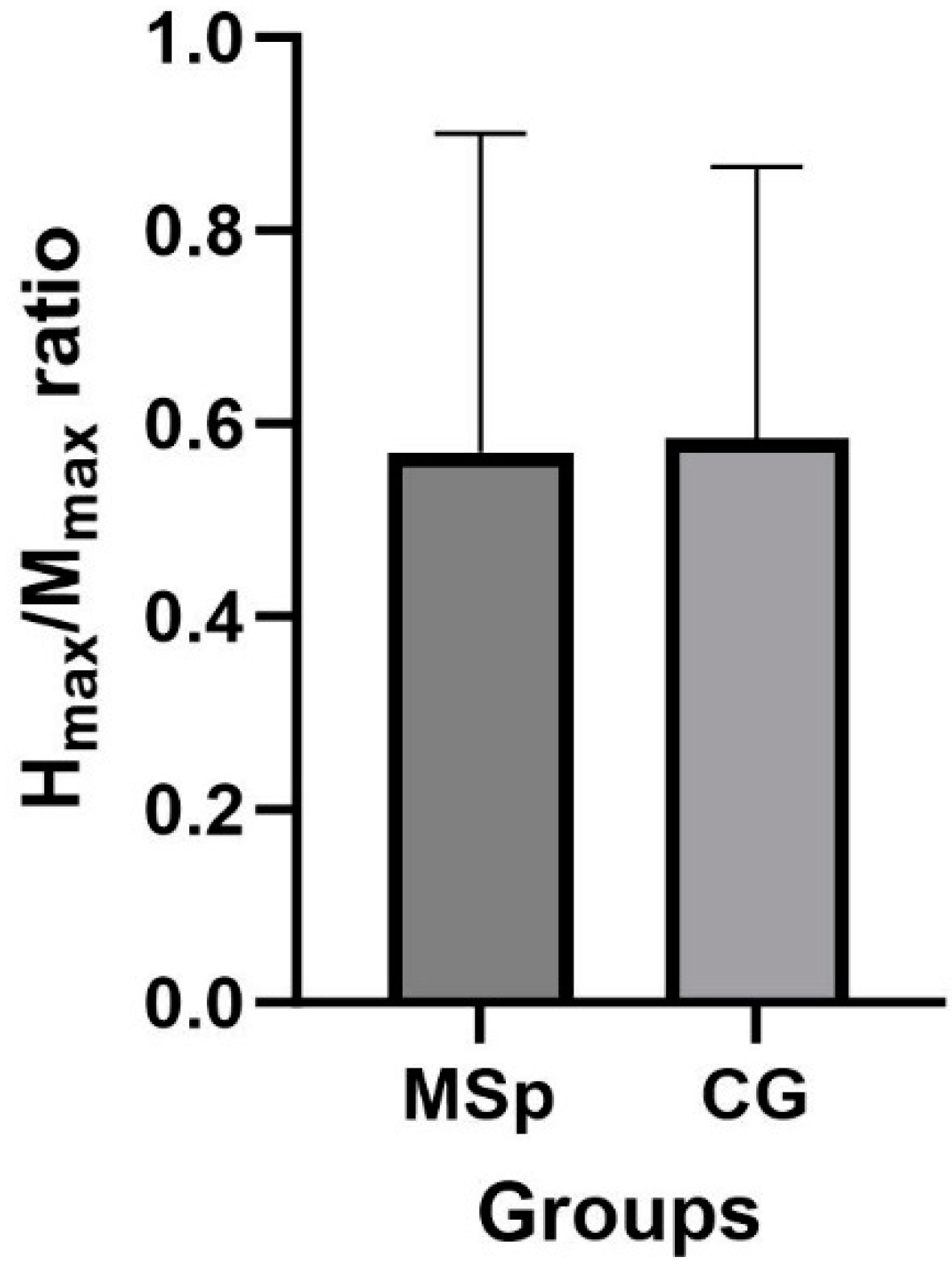

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berer, K.; Krishnamoorthy, G. Microbial View of Central Nervous System Autoimmunity. FEBS Lett 2014, 588, 4207–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.; Ng, H.S.; Poyser, C.; Lucas, R.M.; Tremlett, H. Multiple Sclerosis Incidence: A Systematic Review of Change over Time by Geographical Region. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2022, 63, 103932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milo, R.; Kahana, E. Multiple Sclerosis: Geoepidemiology, Genetics and the Environment. Autoimmun Rev 2010, 9, A387–A394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjartmar, C.; Trapp, B.D. Axonal and Neuronal Degeneration in Multiple Sclerosis: Mechanisms and Functional Consequences. Curr Opin Neurol 2001, 14, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, A.J.; Cox, A.; Le Page, E.; Jones, J.; Trip, S.A.; Deans, J.; Seaman, S.; Miller, D.H.; Hale, G.; Waldmann, H.; et al. The Window of Therapeutic Opportunity in Multiple Sclerosis: Evidence from Monoclonal Antibody Therapy. J Neurol 2006, 253, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.A.; Hadjimichael, O.C.; Preiningerova, J.; Vollmer, T.L. Prevalence and Treatment of Spasticity Reported by Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Multiple Sclerosis 2004, 10, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León, J.; Manuel Morales, J.; Rivera-Navarro, J.; Mitchell, A.J. A Review about the Impact of Multiple Sclerosis on Health-Related Quality of Life. Disabil Rehabil 2003, 25, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motl, R.W.; McAuley, E. Symptom Cluster and Quality of Life: Preliminary Evidence in Multiple Sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs 2010, 42, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgas, U.; Stenager, E.; Ingemann-Hansen, T. Review: Multiple Sclerosis and Physical Exercise: Recommendations for the Application of Resistance-, Endurance- and Combined Training. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2008, 14, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.W.; Arnett, P.A.; Smith, M.M.; Barwick, F.H.; Ahlstrom, B.; Stover, E.J. Worsening of Symptoms Is Associated with Lower Physical Activity Levels in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis 2008, 14, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Martin Ginis, K.A.; Hicks, A.L.; Motl, R.W.; Pilutti, L.A.; Duggan, M.; Wheeler, G.; Persad, R.; Smith, K.M. Development of Evidence-Informed Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults With Multiple Sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013, 94, 1829–1836.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, M.; Dieberg, G.; Smart, N. Exercise as a Therapy for Improvement of Walking Ability in Adults With Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015, 96, 1339–1348.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Pilutti, L.A.; Hicks, A.L.; Martin Ginis, K.A.; Fenuta, A.M.; MacKibbon, K.A.; Motl, R.W. Effects of Exercise Training on Fitness, Mobility, Fatigue, and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Adults With Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review to Inform Guideline Development. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013, 94, 1800–1828.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, H.; Markevics, S.; Haas, B.; Marsden, J.; Freeman, J. Systematic Review: The Effectiveness of Interventions to Reduce Falls and Improve Balance in Adults With Multiple Sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015, 96, 1898–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilutti, L.A.; Dlugonski, D.; Sandroff, B.M.; Klaren, R.; Motl, R.W. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Behavioral Intervention Targeting Symptoms and Physical Activity in Multiple Sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2014, 20, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuspinar, A.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Mayo, N.E. The Effects of Clinical Interventions on Health-Related Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2012, 18, 1686–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgas, U.; Stenager, E.; Sloth, M.; Stenager, E. The Effect of Exercise on Depressive Symptoms in Multiple Sclerosis Based on a Meta-analysis and Critical Review of the Literature. Eur J Neurol 2015, 22, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, S.; McKay, K.A.; Tremlett, H. Physical Activity and Disability Outcomes in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review (2011–2016). Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018, 20, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.; Pilutti, L.A. The Effect of Exercise Training in Adults with Multiple Sclerosis with Severe Mobility Disability: A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2017, 16, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.W.; McAuley, E.; Snook, E.M. Physical Activity and Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Multiple Sclerosis 2005, 11, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrie, R.A.; Horwitz, R.; Cutter, G.; Tyry, T.; Campagnolo, D.; Vollmer, T. High Frequency of Adverse Health Behaviors in Multiple Sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis 2009, 15, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckerman, H.; De Groot, V.; Scholten, M.A.; Kempen, J.C.E.; Lankhorst, G.J. Physical Activity Behavior of People with Multiple Sclerosis: Understanding How They Can Become More Physically Active. Phys Ther 2010, 90, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, S.L.; Jeng, B.; Cutter, G.; Motl, R.W. Perceptions of Physical Activity Guidelines among Wheelchair Users with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahls, T.L.; Reese, D.; Kaplan, D.; Darling, W.G. Rehabilitation with Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Leads to Functional Gains in Ambulation in Patients with Secondary Progressive and Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis: A Case Series Report. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2010, 16, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffiuletti, N.A. Physiological and Methodological Considerations for the Use of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation. Eur J Appl Physiol 2010, 110, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botter, A.; Oprandi, G.; Lanfranco, F.; Allasia, S.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Minetto, M.A. Atlas of the Muscle Motor Points for the Lower Limb: Implications for Electrical Stimulation Procedures and Electrode Positioning. Eur J Appl Physiol 2011, 111, 2461–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, C.S.; Gregory, C.M.; Dean, J.C. Motor Unit Recruitment during Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation: A Critical Appraisal. Eur J Appl Physiol 2011, 111, 2399–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.P.; Armijo Olivo, S.; Magee, D.J.; Gross, D.P. Effectiveness of Interferential Current Therapy in the Management of Musculoskeletal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Phys Ther 2010, 90, 1219–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillard, T.; Noé, F.; Passelergue, P.; Dupui, P. Electrical Stimulation Superimposed onto Voluntary Muscular Contraction. Sports Med 2005, 35, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, P.E.; Campbell, K.E.; Fraser, C.H.; Harris, C.; Keast, D.H.; Potter, P.J.; Hayes, K.C.; Woodbury, M.G. Electrical Stimulation Therapy Increases Rate of Healing of Pressure Ulcers in Community-Dwelling People With Spinal Cord Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010, 91, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberley, T.J.; Lewis, S.M.; Auerbach, E.J.; Dorsey, L.L.; Lojovich, J.M.; Carey, J.R. Electrical Stimulation Driving Functional Improvements and Cortical Changes in Subjects with Stroke. Exp Brain Res 2004, 154, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, G.R.; Harris, R.T.; Woodard, D.; Dudley, G.A. Mapping of Electrical Muscle Stimulation Using MRI. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1993, 74, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergquist, A.J.; Clair, J.M.; Lagerquist, O.; Mang, C.S.; Okuma, Y.; Collins, D.F. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation: Implications of the Electrically Evoked Sensory Volley. Eur J Appl Physiol 2011, 111, 2409–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratchford, J.N.; Shore, W.; Hammond, E.R.; Rose, J.G.; Rifkin, R.; Nie, P.; Tan, K.; Quigg, M.E.; De Lateur, B.J.; Kerr, D.A. A Pilot Study of Functional Electrical Stimulation Cycling in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation 2010, 27, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornusek, C.; Hoang, P. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Cycling Exercise for Persons with Advanced Multiple Sclerosis. J Rehabil Med 2014, 46, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuklass, A.M.; Davis, L.; Hamilton, L.D.; Hebert, J.R.; Alvarez, E.; Enoka, R.M. Pulse Width Does Not Influence the Gains Achieved With Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation in People With Multiple Sclerosis: Double-Blind, Randomized Trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2018, 32, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekmans, T.; Roelants, M.; Feys, P.; Alders, G.; Gijbels, D.; Hanssen, I.; Stinissen, P.; Eijnde, B.O. Effects of Long-Term Resistance Training and Simultaneous Electro-Stimulation on Muscle Strength and Functional Mobility in Multiple Sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2011, 17, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coote, S.; Hughes, L.; Rainsford, G.; Minogue, C.; Donnelly, A. Pilot Randomized Trial of Progressive Resistance Exercise Augmented by Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation for People with Multiple Sclerosis Who Use Walking Aids. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015, 96, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzuola, R.; Labanca, L.; Macaluso, A.; Laudani, L. Modulation of Spinal Excitability Following Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Superimposed to Voluntary Contraction. Eur J Appl Physiol 2020, 120, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzuola, R.; Quinzi, F.; Scalia, M.; Pitzalis, S.; Di Russo, F.; MacAluso, A. Acute Effects of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation on Cortical Dynamics and Reflex Activation. J Neurophysiol 2023, 129, 1310–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalia, M.; Parrella, M.; Borzuola, R.; Macaluso, A. Comparison of Acute Responses in Spinal Excitability between Older and Young People after Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation. Eur J Appl Physiol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerquist, O.; Mang, C.S.; Collins, D.F. Changes in Spinal but Not Cortical Excitability Following Combined Electrical Stimulation of the Tibial Nerve and Voluntary Plantar-Flexion. Exp Brain Res 2012, 222, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, M.; Masugi, Y.; Obata, H.; Sasaki, A.; Popovic, M.R.; Nakazawa, K. Short-Term Inhibition of Spinal Reflexes in Multiple Lower Limb Muscles after Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation of Ankle Plantar Flexors. Exp Brain Res 2019, 237, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laudani, L.; Mira, J.; Carlucci, F.; Orlando, G.; Menotti, F.; Sacchetti, M.; Giombini, A.; Pigozzi, F.; Macaluso, A. Whole Body Vibration of Different Frequencies Inhibits H-Reflex but Does Not Affect Voluntary Activation. Hum Mov Sci 2018, 62, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, S.; Mordillo-Mateos, L.; Dileone, M.; Campolo, M.; Carrasco-Lopez, C.; Moitinho-Ferreira, F.; Gallego-Izquierdo, T.; Siebner, H.R.; Valls-Solé, J.; Aguilar, J.; et al. Effects of Patterned Peripheral Nerve Stimulation on Soleus Spinal Motor Neuron Excitability. PLoS One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Sasaki, A.; Yokoyama, H.; Milosevic, M.; Nakazawa, K. Effects of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation and Voluntary Commands on the Spinal Reflex Excitability of Remote Limb Muscles. Exp Brain Res 2019, 237, 3195–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegrzyk, J.; Fouré, A.; Vilmen, C.; Ghattas, B.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Mattei, J.P.; Place, N.; Bendahan, D.; Gondin, J. Extra Forces Induced by Wide-Pulse, High-Frequency Electrical Stimulation: Occurrence, Magnitude, Variability and Underlying Mechanisms. Clinical Neurophysiology 2015, 126, 1400–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gueugneau, N.; Grosprêtre, S.; Stapley, P.; Lepers, R. High-Frequency Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Modulates Interhemispheric Inhibition in Healthy Humans. J Neurophysiol 2017, 117, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosprêtre, S.; Gueugneau, N.; Martin, A.; Lepers, R. Presynaptic Inhibition Mechanisms May Subserve the Spinal Excitability Modulation Induced by Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2018, 40, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrot-Deseilligny, E.; Mazevet, D. The Monosynaptic Reflex: A Tool to Investigate Motor Control in Humans. Interest and Limits. Neurophysiol Clin 2000, 30, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.; Borich, M.; Sabatier, M.; Backus, D.; Kesar, T. Effects of Downslope Walking on Soleus H-Reflexes and Walking Function in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis: A Preliminary Study. NeuroRehabilitation 2019, 44, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzuola, R.; Nuccio, S.; Scalia, M.; Parrella, M.; Del Vecchio, A.; Bazzucchi, I.; Felici, F.; Macaluso, A. Adjustments in the Motor Unit Discharge Behavior Following Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Compared to Voluntary Contractions. Front Physiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SENIAM. Available online: http://seniam.org/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Zehr, E.P. Considerations for Use of the Hoffmann Reflex in Exercise Studies. Eur J Appl Physiol 2002, 86, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.B.; Estabrooks, K.L.; McGie, S.; Roth, M.J.; Jones, K.E. Quantifying the Effects of Voluntary Contraction and Inter-Stimulus Interval on the Human Soleus H-Reflex. Exp Brain Res 2007, 182, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, H.; Crone, C.; Christenhuis, D.; Petersen, N.T.; Nielsen, J.B. Modulation of Presynaptic Inhibition and Disynaptic Reciprocal Ia Inhibition during Voluntary Movement in Spasticity. Brain 2001, 124, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiest, M.J.; Bergquist, A.J.; Collins, D.F. Torque, Current, and Discomfort During 3 Types of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation of Tibialis Anterior. Phys Ther 2017, 97, 790–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondin, J.; Giannesini, B.; Vilmen, C.; Dalmasso, C.; Le Fur, Y.; Cozzone, P.J.; Bendahan, D. Effects of Stimulation Frequency and Pulse Duration on Fatigue and Metabolic Cost during a Single Bout of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation. Muscle Nerve 2010, 41, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmback, A.M.; Porter, M.M.; Downham, D.; Andersen, J.L.; Lexell, J.; Ck, H.; Maria, A. Structure and Function of the Ankle Dorsiflexor Muscles in Young and Moderately Active Men and Women. J Appl Physiol 2003, 95, 2416–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinar, S.; Kitano, K.; Koceja, D.M. Role of Vision and Task Complexity on Soleus H-Reflex Gain. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2010, 20, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudry, S.; Maerz, A.H.; Enoka, R.M. Presynaptic Modulation of Ia Afferents in Young and Old Adults When Performing Force and Position Control. J Neurophysiol 2010, 103, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koceja, D.M.; Markus, C.A.; Trimble, M.H. Postural Modulation of the Soleus H Reflex in Young and Old Subjects. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1995, 97, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koceja, D.M.; Mynark, R.G. Comparison of Heteronymous Monosynaptic Ia Facilitation in Young and Elderly Subjects in Supine and Standing Positions. Int J Neurosci 2000, 103, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, H.; Shindo, M.; Yanagawa, S.; Yoshida, T.; Momoi, H.; Yanagisawa, N. Progressive Decrease in Heteronymous Monosynaptic Ia Facilitation with Human Ageing. Exp Brain Res 1995, 104, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papegaaij, S.; Taube, W.; Baudry, S.; Otten, E.; Hortobágyi, T. Aging Causes a Reorganization of Cortical and Spinal Control of Posture. Front Aging Neurosci 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudry, S.; Penzer, F.; Duchateau, J. Input-Output Characteristics of Soleus Homonymous Ia Afferents and Corticospinal Pathways during Upright Standing Differ between Young and Elderly Adults. Acta Physiologica 2014, 210, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Wang, C.H.; Hwang, I.S. Characterization of the Mechanical and Neural Components of Spastic Hypertonia with Modified H Reflex. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2006, 16, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pillai, S.; Wolpaw, J.R.; Chen, X.Y. H-Reflex down-Conditioning Greatly Increases the Number of Identifiable GABAergic Interneurons in Rat Ventral Horn. Neurosci Lett 2009, 452, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandolesi, G.; Gentile, A.; Musella, A.; Fresegna, D.; De Vito, F.; Bullitta, S.; Sepman, H.; Marfia, G.A.; Centonze, D. Synaptopathy Connects Inflammation and Neurodegeneration in Multiple Sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2015, 11, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiskamp, M.; Yaqub, M.; van Lingen, M.R.; Pouwels, P.J.W.; de Ruiter, L.R.J.; Killestein, J.; Schwarte, L.A.; Golla, S.S.V.; van Berckel, B.N.M.; Boellaard, R.; et al. Cognitive Performance in Multiple Sclerosis: What Is the Role of the Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid System? Brain Commun 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, J.S.; Scanziani, M. How Inhibition Shapes Cortical Activity. Neuron 2011, 72, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Sejnowski, T.J. Strong Inhibitory Signaling Underlies Stable Temporal Dynamics and Working Memory in Spiking Neural Networks. Nat Neurosci 2021, 24, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, D.; Gros, C.; Badji, A.; Dupont, S.M.; De Leener, B.; Maranzano, J.; Zhuoquiong, R.; Liu, Y.; Granberg, T.; Ouellette, R.; et al. Spatial Distribution of Multiple Sclerosis Lesions in the Cervical Spinal Cord. Brain 2019, 142, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lycklama, G.; Thompson, A.; Filippi, M.; Miller, D.; Polman, C.; Fazekas, F.; Barkhof, F. Spinal-Cord MRI in Multiple Sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2003, 2, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, N.; Nutma, E.; Carassiti, D.; RS Newman, J.; Amor, S.; Altmann, D.R.; Baker, D.; Schmierer, K. Synaptic Loss in Multiple Sclerosis Spinal Cord. Ann Neurol 2020, 88, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, M.A. Widespread Synaptic Loss in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain 2016, 139, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, N.; Carassiti, D.; Altmann, D.R.; Baker, D.; Schmierer, K. Axonal Loss in the Multiple Sclerosis Spinal Cord Revisited. Brain Pathology 2018, 28, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, G.C.; Ebers, G.C.; Esiri, M.M. Axonal Loss in Multiple Sclerosis: A Pathological Survey of the Corticospinal and Sensory Tracts. Brain 2004, 127, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkjaer, T.; Toft, E.; Hansen, H.J. H-Reflex Modulation during Gait in Multiple Sclerosis Patients with Spasticity. Acta Neurol Scand 1995, 91, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnoff, J.J.; Motl, R.W. Effect of Acute Unloaded Arm versus Leg Cycling Exercise on the Soleus H-Reflex in Adults with Multiple Sclerosis. Neurosci Lett 2010, 479, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnoff, J.J.; Shin, S.; Motl, R.W. Multiple Sclerosis and Postural Control: The Role of Spasticity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010, 91, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.W.; Snook, E.M.; Hinkle, M.L.; McAuley, E. Effect of Acute Leg Cycling on the Soleus H-Reflex and Modified Ashworth Scale Scores in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis. Neurosci Lett 2006, 406, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantrell, G.S.; Lantis, D.J.; Bemben, M.G.; Black, C.D.; Larson, D.J.; Pardo, G.; Fjeldstad-Pardo, C.; Larson, R.D. Relationship between Soleus H-Reflex Asymmetry and Postural Control in Multiple Sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2022, 44, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammali, F.; Xu, L.; Rabotti, C.; Cardinale, M.; Xu, Y.; van Dijk, J.P.; Zwarts, M.J.; Del Prete, Z.; Mischi, M. Effects of Vibration-Induced Fatigue on the H-Reflex. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2018, 39, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PRE | POST | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISO | MSp | 0.39 ± 0.29 | 0.38 ± 0.28 | 0.506 |

| CG | 0.50 ± 0.24 | 0.50 ± 0.27 | 0.829 | |

| pNMES | MSp | 0.42 ± 0.34 | 0.39 ± 0.32 | 0.068 |

| CG | 0.49 ± 0.22 | 0.40 ± 0.20* | 0.000 | |

| NMES+ | MSp | 0.40 ± 0.34 | 0.39 ± 0.31 | 0.126 |

| CG | 0.48 ± 0.22 | 0.54 ± 0.25* | 0.010 |

| Pre-test | Post-test | |

|---|---|---|

| MSp | 43.12 ± 15.1 | 40.86 ± 15.48 |

| CG | 53.43 ± 27.29 | 54.2 ± 26.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).