1. Introduction

The oral cavity hosts its characteristic microbiota, which comprises more than 700 different kinds of microorganisms, spread out in specific niches including the tongue, cheeks, hard and soft palates, saliva, teeth, throat, and gingival sulcus [

1,

2,

3].

The interaction between the oral microbiota and the host is complex, since the former creates a polymicrobial biofilm that strongly attached to oral surfaces and comprehend commensal and pathogenic bacteria, and other microorganisms such as yeasts, fungi, and viruses [

1,

4]. In particular, bacterial communities in the mouth mainly belong to six major phyla (Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Spirochaetes, and Fusobacteria) [

3].

In the presence of risk factors, such as an unbalanced diet, smoke, improper hygiene practices, or antibiotic use, the microbial community can shift to a dysbiotic state, in which an increase in the number of pathogenic bacteria and the production of virulence factors occurs [

5]. The dysbiosis of the microbiota is linked to the onset or progression of many oral diseases, such as dental caries, periodontitis, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, and even tumors, as well as extra-oral pathologies, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [

3,

6,

7].

Among the pathogenic bacteria,

Streptococcus mutans is a Gram-positive facultative anaerobe and it is considered the major contributor to dental caries and teeth decay due to its acidogenic and aciduric properties, in addition to the capacity to synthesize large amounts of extracellular polymers composed of glucan [

8,

9]. It forms biofilm on tooth surfaces - the so-called dental plaque - and it has been associated also with extraoral pathologies, such as infective endocarditis or atherosclerosis [

9].

HACEK microorganisms are Gram-negative bacteria naturally resident in the oropharyngeal mucosa, comprising

Haemophilus spp.,

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans,

Cardiobacterium hominis,

Eikenella corrodens, and

Kingella kingae. The uncontrolled proliferation of these bacteria can lead to a broad range of infections, with infective endocarditis being a notable manifestation [

10]. Among them,

A. actinomycetemcomitans is a facultative anaerobe, oral commensal bacterium which can behave as an opportunistic pathogen [

11]. In predisposing conditions, it can determine an excessive inflammatory response that leads to aggressive periodontitis, avoiding the correct periodontal tissue remodeling [

12]. Additionally, certain serotypes possess cytokine-binding molecules able to influence the host’s immune system [

13]. Moreover, some

A. actinomycetemcomitans strains have been associated with the risk of coronary artery disease development [

14].

Periodontal pathogens modulate the immune response causing imbalances not only in the site they are colonizing but also at a systemic level. Indeed, periodontal infections have been linked to several pathologies in distant organs, such as gastrointestinal and colorectal cancers, diabetes, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular diseases, and increased risk of development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, type 2 diabetes, and atherosclerotic vascular diseases [

9,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

The standard treatment for chronic oral diseases is non-surgical periodontal therapy, including oral hygiene procedures, scaling, and root planing. In such cases, the use of antiseptic (e.g., chlorhexidine) or antibiotics as supplemental therapy can be helpful if the standard treatment alone is not effective [

21]. Nevertheless, the constant use of antiseptics and antibiotics increases the resistance of oral pathogens to these substances or result in dysbiosis, promoting the proliferation of pathogenic/opportunistic bacteria [

22]. The issue of antibiotic resistance it is increasing over the years, thus leading to the urgent need for new types of alternative treatments.

Probiotic-based adjuvant therapies may be useful for treating or even prevent these chronic infections and restoring the oral microbiota, achieving benefits for oral health and the overall well-being [

21,

23,

24,

25]. The major goal of probiotic treatment is to enhance the presence of beneficial commensal bacteria, which might be able to trigger an anti-inflammatory response as well as an antibacterial and anti-adhesive effect against pathogenic microbes [

26,

27,

28].

In this scenario, the present study aims to set up a preliminary in vitro screening to investigate the antimicrobial and anti-adhesive properties of specific probiotic strains against two main pathogens of the oral cavity, S. mutans and A. actinomycetemcomitans, to exploit their biotherapeutic potential for human health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial strain cultures

2.1.1. Probiotic strains

Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains used in this study are deposited in the German or Belgian cell culture collections of microorganisms (DSMZ and LMG, respectively). Lactobacillus acidophilus PBS066 (DSM 24936), Lactobacillus crispatus LCR030 (LMG P-31003), Lactobacillus gasseri LG050 (LMG P-29638), Lactiplantibacillus plantarum PBS067 (DSM 24937), Limosilactobacillus reuteri PBS072 (DSM 25175), Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus LRH020 (DSM 25568), Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BL050 (DSM 25566), Lacticaseibacillus paracasei LPC 1101 (DSM 34558), Lacticaseibacillus paracasei LPC 1082 (DSM 34557), and Lacticaseibacillus paracasei LPC 1114 (DSM 34559) were cultured overnight at 37 ± 1 °C in De Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) broth (VWR International Srl, Milan, Italy). All the lactic acid bacteria were kindly provided by Synbalance Srl (Origgio, Varese, Italy).

2.1.2. Pathogen strains

Streptococcus mutans (purchased from American type culture collection, Manassas, USA; ATCC 700610, Gram positive) and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (DSM 11123, Gram negative) were chosen as representative oral pathogens. The pathogens were cultured overnight at 37 °C in brain heart infusion and tryptic soy broth (BHI and TSB, both from Biolife Italia Srl, Milan, Italy), respectively.

All the bacterial strains were freshly renewed before each experiment.

2.2. Screening of probiotic antibacterial effect by agar overlay assay

The overlay assay was performed on agar plates where a probiotic strain with potential bacteriocin production was drop-spotted and then overlaid on the top with a layer of soft agar containing a pathogen strain to be tested for bacteriocin sensitivity [

29,

30].

2.2.1. Preventive experiments

This set of experiments aimed to determine the possible effect of the probiotic strains in the inhibition of the pathogen growth when applied before the infection.

Briefly, 10 μl of each probiotic strain were spotted on the surface of a MRS agar plate and the drops were allowed to dry under a laminar flow hood. Plates were incubated for 48 hours (h) at 37 ± 1°C in anaerobic conditions by using Anaerocult A (Millipore, distributed by VWR International Srl) to allow the development of colonies. Then, 10 μl of S. mutans or A. actinomycetemcomitans were inoculated in 10 ml of the proper melted soft agar medium (BHI or TSB, respectively, containing 7.5 g/L of agar) and poured on top of the MRS agar plates spotted with probiotics. The plates were incubated at 37 °C ± 1 for 24 h.

2.2.2. Treatment experiments

This set of experiments differed from the previous one since the probiotics were seeded in the moment of the establishment of the infection, so both probiotics and pathogens were put together almost simultaneously.

Briefly, 10 μl of each probiotic were drop-spotted on a MRS agar plate. Immediately after the drops dried, the pathogens were inoculated in the proper soft agar medium and poured as mentioned before to overlay the probiotics spotted onto MRS plates. All the plates were then incubated at 37 ± 1 °C for 24 h.

Since LAB metabolism induce an acidification of the medium, pristine MRS broth at pH 4.5 was used as control to exclude the potential effect of acidic pH on S. mutans and A. actinomycetemcomitans growth.

Inhibitory properties of the probiotic strains against the pathogenic bacteria were evaluated by measuring the diameter of the inhibition halos after incubation. Each zone was measured in different directions to ensure that diameter measurements were representative. All the experiments were performed in triplicates and repeated 3 times independently.

2.3. Colony Forming Unit (CFU) count of adherent cells in the preventive model and image acquisition

To further investigate and confirm the results obtained in the preventive model of the agar overlay assay in which the LAB demonstrated to perform better than in the treatment one, probiotic strains with the stronger effect against both the pathogens tested were analysed also by using CFU.

Briefly, 50 μl of overnight probiotic culture of L. crispatus LCR030, L. gasseri LG050, L. plantarum PBS067, L. rhamnosus LRH020, L. paracasei LPC 1101, L. paracasei LPC 1082, and L. paracasei LPC 1114 (≈10

9 colony forming unit/ml, CFU/ml) were drop-spotted in the centre of sterile glass coverslips (12 mm diameter, Waldemar Knittel Glasbearbeitungs GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) in a 24 multi-well plate (Biosigma, Cona, Venice, Italy) and incubated at 37 °C for 90 minutes (min) to allow them to adhere to the surface [

31]. A drop of pristine MRS broth was used as control. The remaining drops containing non-adherent cells were removed and 50 μl of each pathogen, adjusted in sterile phosphate buffer saline 1X (PBS, VWR International Srl) at a concentration of 10

6 CFU/ml, were drop-spotted on top of the probiotic adherent cells. The multi-well plates were then incubated for 24 h at 37 ± 1 °C.

To perform CFU counts of adherent cells, the coverslips were sonicated (Sonica 3200MH S3, Soltec Srl, Milan, Italy) in 1 ml of sterile PBS 1X to mechanically detach all the adherent bacteria. Several serial dilutions were performed and plated on homofermentative-heterofermentative differential (HHD, Biolife Italiana Srl) agar medium to discriminate the pathogen from the probiotic cells thanks to their different morphology. Since HHD is a preferred medium for LAB but not for other genera, we tested the ability of the two pathogens tested to grow in this condition and to form colonies in a comparable amount with respect to their preferred medium. The plates were incubated for 24-48 h at 37 ± 1 °C and the pathogen colonies were counted. All the experiments were performed in triplicates and repeated 3 times independently.

Finally, the morphology and presence of the bacterial cells was investigated by scanning electron microscopy. Briefly, the coverslips prepared as previously described were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, US) and left overnight at 4 °C. Then, to allow a complete dehydration of the samples, an ethanol scale (from 70 to 100 %, 1 h each; Merck, Italy) was performed. Subsequently, hexamethyldisilazane (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, US) was added for 20 min to prevent the collapse of the bacterial cell structure. Samples were then coated with a thin layer of gold using a sputter coater machine (DII-29030SCTR Smart Coater, JEOL SpA, Basiglio, Milan, Italy). The images were acquired by using a bench Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM, JSM-IT500, JEOL SpA) at different magnifications (5,000X and 10,000X).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was performed using the GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www. graph pad. com). Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was fixed at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Antibacterial properties of probiotic strains

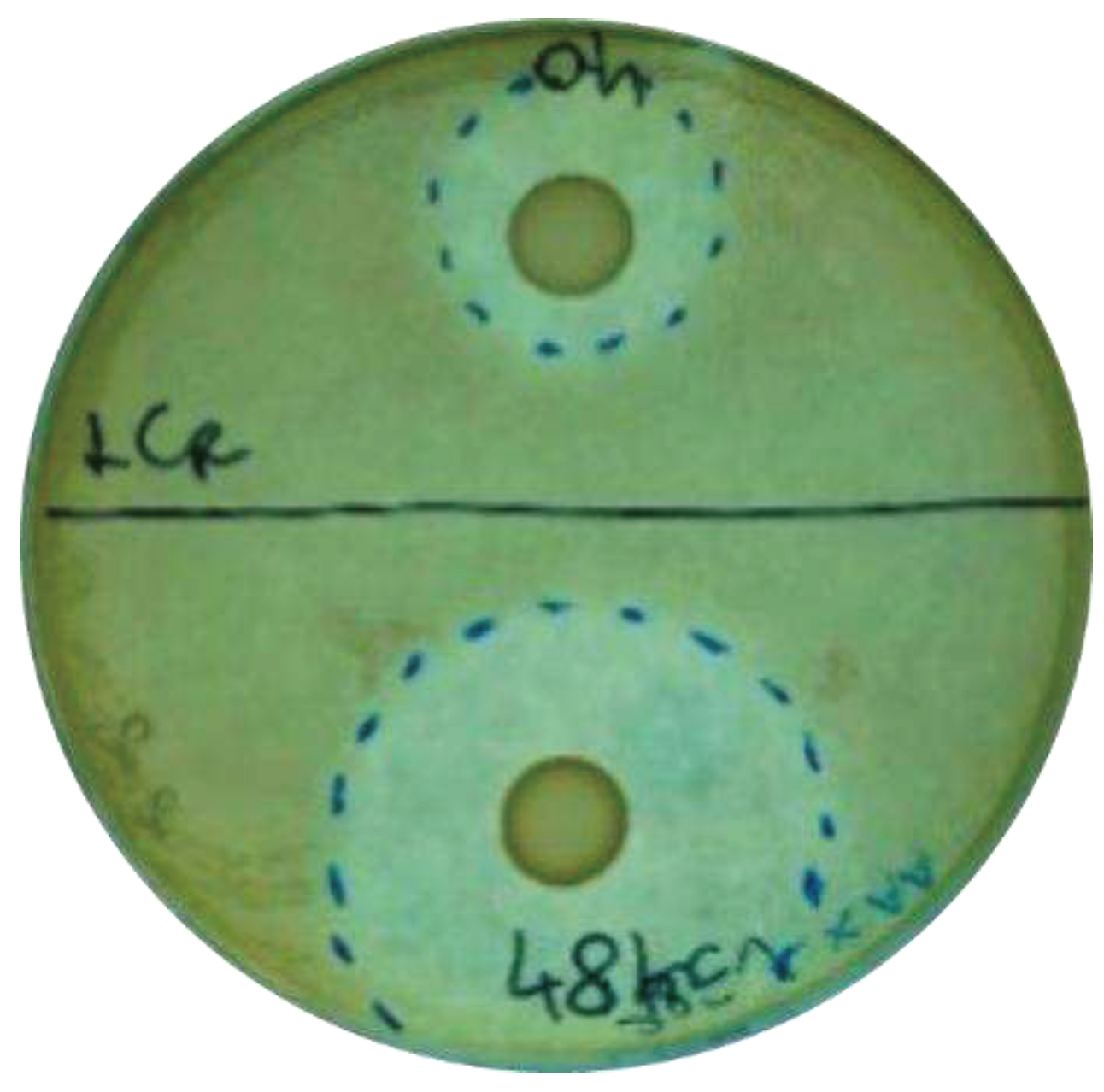

Ten probiotic strains were firstly screened for their antibacterial properties against S. mutans and A. actinomycetemcomitans by using an agar overlay assay. The inhibition halos were measured after 24 h of incubation. The results of the treatment and preventive models were compared to evaluate whether the antibacterial effect could be exerted only if the antimicrobial compounds accumulate in the environment together with colony formation, or if they could be effective also at the time of the infection establishment.

All the probiotic strains tested were able to counteract the pathogen growth in both the preventive and treatment experiments. As expected, the preventive model results demonstrated a greater inhibition of pathogens with respect to the treatment one, except for L. reuteri PBS072, which did not improve the inhibition zone in the preventive model (

Table 1;

Figure 1).

In the preventive model, L. crispatus LCR030 and L. paracasei LPC 1101 produced halos with diameters > 45 mm, showing the strongest effect against S. mutans, while against A. actinomycetemcomitans the same result was achieved by L. gasseri LG050, L. plantarum PBS067, and L. paracasei LPC 1114 (

Table 1).

In the treatment assays, many probiotic strains were active against S. mutans in an intermediate way, showing diameter halos ranging from 16 to 30 mm, with the exception of L. gasseri LG050 and B. lactis BL050 which had a lower effect. The best probiotic performers against A. actinomycetemcomitans were instead L. gasseri LG050 and L. plantarum PBS067, showing diameter halos ranging from 31 to 45 mm (

Table 1).

Considering all the conditions, the strains that showed the strongest inhibition against the tested pathogens in both models were L. crispatus LCR030, L. gasseri LG050, L. plantarum PBS067, L. rhamnosus LRH020, L. paracasei LPC 1101, L. paracasei LPC 1082, and L. paracasei LPC 1114.

3.2. Inhibition of pathogen adhesion and growth by probiotic strains

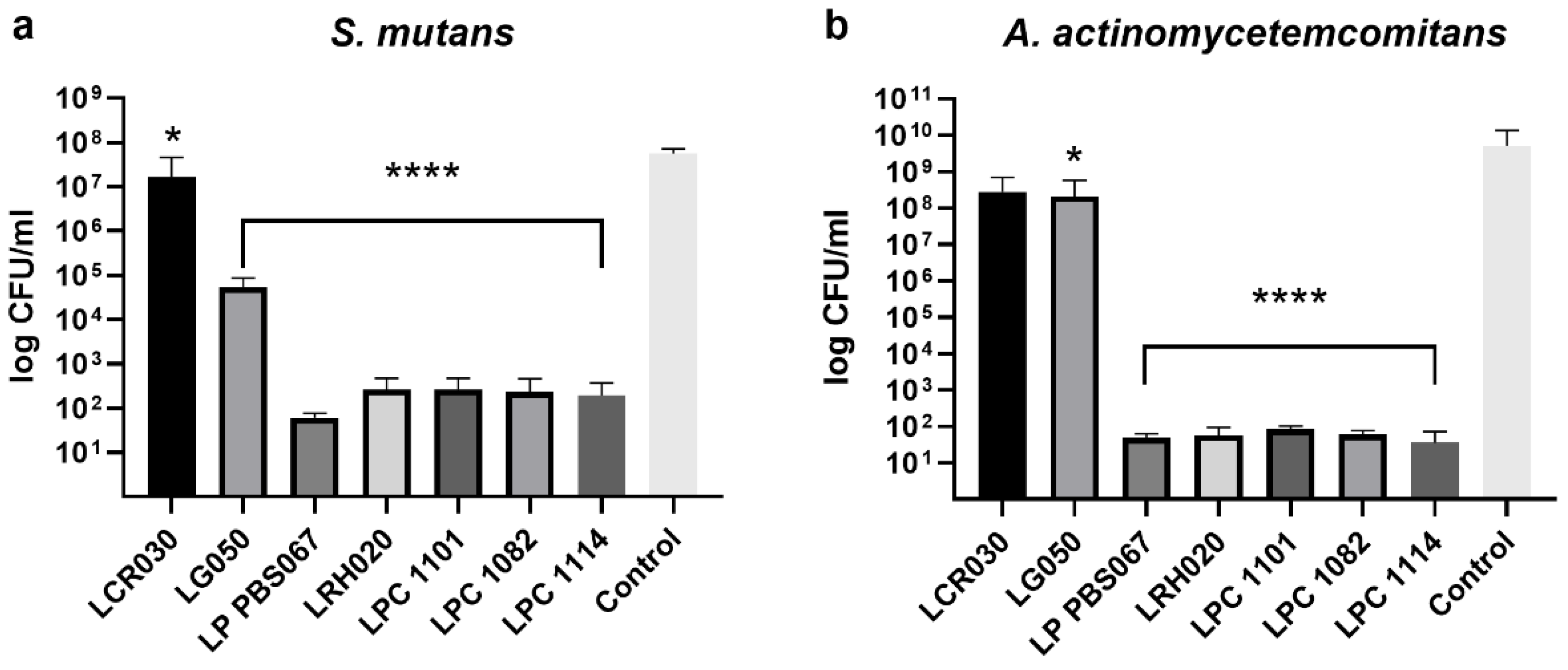

The agar overlay assay revealed better performances of the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in the preventive experiments rather than in the treatment model, so we deepen this aspect in the following assay. Seven out of ten probiotic strains which determined the greater inhibition zones (L. crispatus LCR030, L. gasseri LG050, L. plantarum PBS067, L. rhamnosus LRH020, L. paracasei LPC 1101, L. paracasei LPC 1082, and L. paracasei LPC 1114) were further investigated for their anti-adhesive properties against the two tested pathogens through CFU counts.

All probiotic strains reduced the number of pathogen cells able to adhere and subsequently replicate with respect to the control. L. crispatus LCR030 demonstrated a significant effect against S. mutans but not A. actinomycetemcomitans. Conversely, L. gasseri LG050 showed a significant inhibition against A. actinomycetemcomitans but not S. mutans (

Figure 2).

L. plantarum PBS067, L. rhamnosus LRH020, L. paracasei LPC 1101, L. paracasei LPC 1082, and L. paracasei LPC 1114 induced a very significant decrease in cell adhesion of both S. mutans and A. actinomycetemcomitans and, as a consequence, a reduction in the CFU count (p<0.0001;

Figure 2 a and b, respectively).

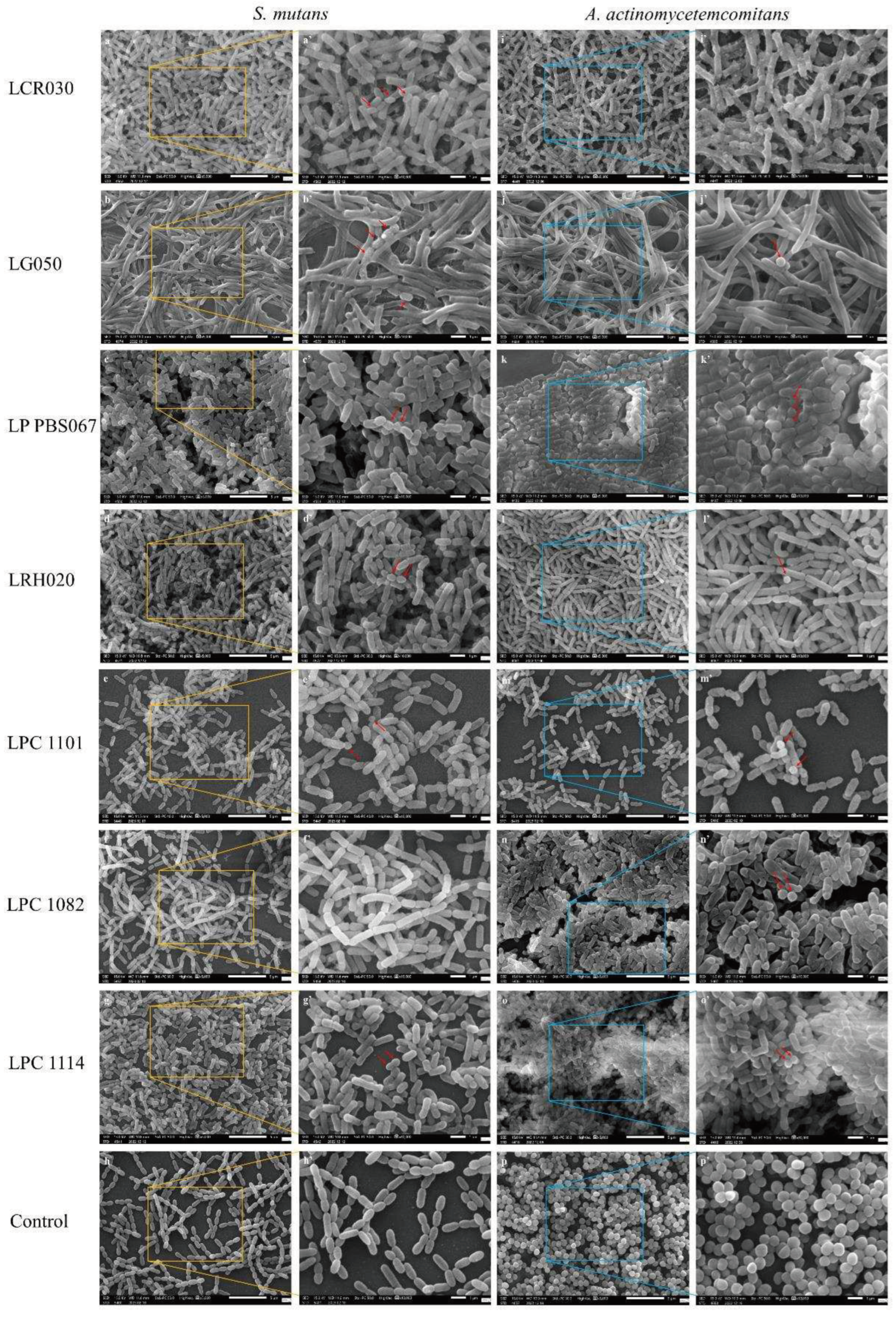

The results described above were further confirmed by SEM images, which highlighted that the pathogenic bacteria were hindered from adhering to the probiotic layer formed during the pre-incubation time, resulting in a nearly complete prevention of colonization (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

Probiotics are non-pathogenic live and Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) microorganisms, mainly bacteria, which can benefit the hosts’ health if given in an appropriate amount [

32]. Although the role of probiotics in the oral cavity has only recently been hypothesized and thus is still under-researched, the international literature already suggests that their use can be considered beneficial, given their ability to limit the development of pathogenic colonies [

33].

We consider two pivotal periodontal pathogens,

S. mutans and

A. actinomycetemcomitans, which trigger dental caries and periodontitis. Indeed, it is widely recognized that

S. mutans adhere to the tooth enamel and use extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) to build biofilms, resulting in dental caries consequently [

34,

35].

A. actinomycetemcomitans can contribute to infections of the periodontal tissues and harm the alveolar bone and periodontal ligaments, determining periodontal disease [

35,

36].

In addition to creating oral discomforts at the site of bacterial colonization, periodontal infections also affect the immune system systemically. In fact, a number of diseases in anatomically distant organs have been connected to periodontal infections [

37]. It has been demonstrated that bacteria belonging to the oral cavity of subjects affected by periodontitis can disseminate through the vascular system, sustaining the inflammatory process by cytokine release and participating in cardiovascular diseases, atherosclerotic lesion onset or progression, neuroinflammation, and diabetes [

38,

39,

40,

41].

A. actinomycetemcomitans is recognized as a bacterial initiator of autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [

42]. Moreover, the damaged oral mucosal barrier resulting from periodontal disease can lead to the translocation of citrullinated oral bacteria into the circulatory system. This event activates both innate and adaptive immune response, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of RA [

43].

In this context, the present study aims to evaluate the antibacterial and antiadhesive properties of a wide range of probiotic strains against

S. mutans and

A. actinomycetemcomitans. A successful method to screen various probiotic strains for bacteriocin-mediated competitive interactions is to use the overlay assay [

29]. To determine the strain-specific activity, we performed a first screening on ten probiotic strains to detect antibacterial compound production. In the preventive model, the formation of probiotic colonies and accumulation of probiotic metabolites was allowed by a pre-incubation of 48 h with respect to the infection, while in the treatment model a simultaneous incubation of probiotic and pathogen strains was performed. The results demonstrated all the tested LAB have a positive effect in the containment of pathogen growth but only some of them induce a substantial reduction in this parameter; furthermore, the preventive model activity resulted more effective than the treatment assay. As highlighted by a recent review, probiotic bacteria may stimulate an immune response against pathogens, inhibiting the growth of bacteria that cause dental cavities and periodontal diseases, and preventing inflammation and damage to tissue in the oral cavity [

44].

Following this first screening selection, a series of seven strains were tested to understand their anti-adhesive properties with respect to

S. mutans and

A. actinomycetemcomitans.

L. crispatus LCR030 and

L. gasseri LG050 confirmed their efficacy against

S. mutans and

A. actinomycetemcomitans, respectively.

L. plantarum PBS067,

L. rhamnosus LRH020,

L. paracasei LPC 1101,

L. paracasei LPC 1082, and

L. paracasei LPC 1114 induced a very significant decrease in cell count and adhesion of both pathogens. LAB have a greater adherence to tissues and can compete with pathogens for growth factors, nutrition, and adhesion surfaces. This phenomenon happens not only in the intestinal mucosa but also in the oral cavity, where, after adhering, probiotics group together and produce antimicrobial substances such as acids, bacteriocins, and peroxides which prevent pathogenic bacteria from adhering and forming biofilm [

27,

44,

45]. Recently, several researches have been interested in the probiotic role in the prevention or eradication of bacterial biofilm on medical devices (i.e., different implants, artificial veins, or catheters). The competitive behaviour of probiotics and/or their metabolites indeed hinder the pathogen attachment to medical device surfaces and inhibit their adhesion and aggregation; they also express disruptive properties against the pre-formed pathogen biofilms [

46,

47,

48]. It is worth mentioning that LAB exert strain-specific probiotic properties. For example, the antimicrobial and antiadhesive properties of

L. plantarum PBS067 and

L. rhamnosus LRH020 were already demonstrated in the context of urogenital infections in human bladder epithelia, where the probiotics were able to co-aggregate with urogenital pathogens, limiting the colonization [

49].

The use of probiotics as adjuvant treatment in different diseases seems promising, as many beneficial effects have been already demonstrated, firstly in the rebalance of the gut microbiota and then also systemically [

50]. Diverse

Lactobacillus species exhibit immunomodulatory activities in the host gut, including enhanced antioxidant status and production of adhesion molecules and preventing the establishment of neutrophil extracellular traps [

51,

52]. Gout and hyperuricemia, osteoarthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, RA, osteoporosis and osteoopenia, psoriasis, and spondyloarthritis may all be improved by probiotic supplementation [

53]. An osteoarthritis rat model showed decreased pain severity, inflammation, and cartilage destruction when treated with

L. rhamnosus [

54].

5. Conclusions

The effects of specific probiotics can be considered as a promising intervention to limit oral pathogen growth within the oral cavity, thereby reducing their potential dissemination to distant anatomical niches. The anti-adhesive and anti-biofilm properties exhibited by selected probiotic strains, such as L. plantarum PBS067, L. rhamnosus LRH020, L. paracasei LPC 1101, L. paracasei LPC 1082, and L. paracasei LPC 1114, can be considered crucial to set the basis for further investigation to better clarify their mechanism of action.

In a future perspective, probiotic supplementation could be a complementary and alternative approach to classical medications to guarantee not only oral but also systemic health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F.S., A.C. and P.M.; methodology, A.C.S. and P.M.; validation, F.D.A., A.C.S and Z.N.; formal analysis, F.D.A.; investigation, F.D.A., A.C.S and Z.N.; data curation, F.D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.F.S. and F.D.A.; writing—review and editing, D.F.S., F.D.A. and A.C.S.; visualization, D.F.S.; supervision, P.M.; project administration, P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Synbalance Srl.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

P.M. and D.F.S. are Synbalance employees. The funders had no role in the collection, analyses, interpretation of data, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Deo, P.; Deshmukh, R. Oral Microbiome: Unveiling the Fundamentals. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2019, 23, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.G.; Sarkar, S.; Umar, S.; Lee, S.T.M.; Thomas, S.M. The Contribution of the Human Oral Microbiome to Oral Disease: A Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Ni, C.; Du, Z.; Yan, F. Human Oral Microbiota and Its Modulation for Oral Health. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 99, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Song, Z. The Oral Microbiota: Community Composition, Influencing Factors, Pathogenesis, and Interventions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 895537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.J.; Koo, H.; Hajishengallis, G. The Oral Microbiota: Dynamic Communities and Host Interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Luo, B.; Cui, J.; Huang, L.; Chen, K.; Liu, Y. The Oral Microbiota and Cardiometabolic Health: A Comprehensive Review and Emerging Insights. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1010368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges, F.M.; Do, N.T.; Seleem, D. Oral Dysbiosis and Systemic Diseases. Front. Dent. Med 2022, 3, 995423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, E.L.; Beall, C.J.; Kutsch, S.R.; Firestone, N.D.; Leys, E.J.; Griffen, A.L. Beyond Streptococcus Mutans: Dental Caries Onset Linked to Multiple Species by 16S rRNA Community Analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, J.A.; Palmer, S.R.; Zeng, L.; Wen, Z.T.; Kajfasz, J.K.; Freires, I.A.; Abranches, J.; Brady, L.J. The Biology of Streptococcus Mutans. Microbiol Spectr 2019, 7, 7.1.03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaledi, M.; Sameni, F.; Afkhami, H.; Hemmati, J.; Asareh Zadegan Dezfuli, A.; Sanae, M.-J.; Validi, M. Infective Endocarditis by HACEK: A Review. J Cardiothorac Surg 2022, 17, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, M. Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans – A Tooth Killer? JCDR 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, B.A.; Novince, C.M.; Kirkwood, K.L. Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans, a Potent Immunoregulator of the Periodontal Host Defense System and Alveolar Bone Homeostasis. Molecular Oral Microbiology 2016, 31, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belibasakis; Maula; Bao; Lindholm; Bostanci; Oscarsson; Ihalin; Johansson Virulence and Pathogenicity Properties of Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans. Pathogens 2019, 8, 222. [CrossRef]

- Pietiäinen, M.; Kopra, K.A.E.; Vuorenkoski, J.; Salminen, A.; Paju, S.; Mäntylä, P.; Buhlin, K.; Liljestrand, J.M.; Nieminen, M.S.; Sinisalo, J.; et al. Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans Serotypes Associate with Periodontal and Coronary Artery Disease Status. J Clinic Periodontology 2018, 45, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, F.Q.; Almeida-da-Silva, C.L.C.; Huynh, B.; Trinh, A.; Liu, J.; Woodward, J.; Asadi, H.; Ojcius, D.M. Association between Periodontal Pathogens and Systemic Disease. Biomedical Journal 2019, 42, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahekar, A.A.; Singh, S.; Saha, S.; Molnar, J.; Arora, R. The Prevalence and Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease Is Significantly Increased in Periodontitis: A Meta-Analysis. American Heart Journal 2007, 154, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, L.L.; Fu, R.; Buckley, D.I.; Freeman, M.; Helfand, M. Periodontal Disease and Coronary Heart Disease Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J GEN INTERN MED 2008, 23, 2079–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, M.; Naka, S.; Nakano, K.; Wada, K.; Endo, H.; Mawatari, H.; Imajo, K.; Nomura, R.; Hokamura, K.; Ono, M.; et al. Involvement of a Periodontal Pathogen, Porphyromonas Gingivalis on the Pathogenesis of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. BMC Gastroenterol 2012, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimatsu, K.; Yamada, H.; Miyazawa, H.; Minagawa, T.; Nakajima, M.; Ryder, M.I.; Gotoh, K.; Motooka, D.; Nakamura, S.; Iida, T.; et al. Oral Pathobiont Induces Systemic Inflammation and Metabolic Changes Associated with Alteration of Gut Microbiota. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chávarry, N.G.M.; Vettore, M.V.; Sansone, C.; Sheiham, A. And DTehsetrRuecltaivtieonPsehriipodBoenttwaleeDnisDeaiasbee:tAesMMeetall-iANtORuonIGtsIaNftoeAClrLsoysAPpsReuyTbniIrCsliciLgceEation. Oral Health 2009, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Brody, H.; Radaic, A.; Kapila, Y. Probiotics for Periodontal Health—Current Molecular Findings. Periodontology 2000 2021, 87, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verspecht, T.; Rodriguez Herrero, E.; Khodaparast, L.; Khodaparast, L.; Boon, N.; Bernaerts, K.; Quirynen, M.; Teughels, W. Development of Antiseptic Adaptation and Cross-Adapatation in Selected Oral Pathogens in Vitro. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetta, P.; Ormelli, M.; Amoruso, A.; Pane, M.; Azzimonti, B.; Squarzanti, D.F. Probiotics as Potential Biological Immunomodulators in the Management of Oral Lichen Planus: What’s New? IJMS 2022, 23, 3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, S.; Sin, M. Can Probiotics Prevent Dental Caries? Evidence-Based Dentistry 2023, 24, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaźmierczyk-Winciorek, M.; Nędzi-Góra, M.; Słotwińska, S.M. The Immunomodulating Role of Probiotics in the Prevention and Treatment of Oral Diseases. Central European Journal of Immunology 2021, 46, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezow, A.B.; Darveau, R.P. Microbial Shift and Periodontitis. Periodontology 2000 2011, 55, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Invernici, M.M.; Salvador, S.L.; Silva, P.H.F.; Soares, M.S.M.; Casarin, R.; Palioto, D.B.; Souza, S.L.S.; Taba, M.; Novaes, A.B.; Furlaneto, F.A.C.; et al. Effects of Bifidobacterium Probiotic on the Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clinic Periodontology 2018, 45, 1198–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowiak, P.; Śliżewska, K. Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Human Health. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricic, N.; Dawid, S. Using the Overlay Assay to Qualitatively Measure Bacterial Production of and Sensitivity to Pneumococcal Bacteriocins. JoVE 2014, 51876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.L.; Hammer, K.; Lim, L.Y.; Hettiarachchi, D.; Locher, C. Optimisation of an Agar Overlay Assay for the Assessment of the Antimicrobial Activity of Topically Applied Semi-Solid Antiseptic Products Including Honey-Based Formulations. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2022, 202, 106596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawistowska-Rojek, A.; Kośmider, A.; Stępień, K.; Tyski, S. Adhesion and Aggregation Properties of Lactobacillaceae Strains as Protection Ways against Enteropathogenic Bacteria. Archives of Microbiology 2022, 204, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics Consensus Statement on the Scope and Appropriate Use of the Term Probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminario-Amez, M.; Lopez-Lopez, J.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; Ayuso-Montero, R.; Jane-Salas, E. Probiotics and Oral Health: A Systematic Review. Med Oral 2017, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssten, S.D.; Björklund, M.; Ouwehand, A.C. Streptococcus Mutans, Caries and Simulation Models. Nutrients 2010, 2, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriswandini, I.L.; Diyatri, I.; Tantiana; Nuraini, P.; Berniyanti, T.; Putri, I.A.; Tyas, P.N.B.N. The Forming of Bacteria Biofilm from Streptococcus Mutans and Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans as a Marker for Early Detection in Dental Caries and Periodontitis. Infectious Disease Reports 2020, 12, 8722. [CrossRef]

- Fine, D.H.; Patil, A.G.; Velusamy, S.K. Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) Under the Radar: Myths and Misunderstandings of Aa and Its Role in Aggressive Periodontitis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, R.; Badran, Z.; Boghossian, A.; Alharbi, A.M.; Alfahemi, H.; Khan, N.A. The Increasing Importance of the Oral Microbiome in Periodontal Health and Disease. Future Science OA 2023, 9, FSO856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, B.; Fazal, I.; Khan, S.F.; Nambiar, M.; Irfana, D.K.; Prasad, R.; Raj, A. Association between Cardiovascular Diseases and Periodontal Disease: More than What Meets the Eye. dti 2023, 17, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenkein, H.A.; Papapanou, P.N.; Genco, R.; Sanz, M. Mechanisms Underlying the Association between Periodontitis and Atherosclerotic Disease. Periodontology 2000 2020, 83, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarhoumi, R.; Alvarez, C.; Harris, T.; Tognoni, C.M.; Paster, B.J.; Carreras, I.; Dedeoglu, A.; Kantarci, A. Microglial Cell Response to Experimental Periodontal Disease. J Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Păunică, I.; Giurgiu, M.; Dumitriu, A.S.; Păunică, S.; Pantea Stoian, A.M.; Martu, M.-A.; Serafinceanu, C. The Bidirectional Relationship between Periodontal Disease and Diabetes Mellitus—A Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konig, M.F.; Abusleme, L.; Reinholdt, J.; Palmer, R.J.; Teles, R.P.; Sampson, K.; Rosen, A.; Nigrovic, P.A.; Sokolove, J.; Giles, J.T.; et al. Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans –Induced Hypercitrullination Links Periodontal Infection to Autoimmunity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, R.C.; Lanz, T.V.; Hale, C.R.; Sepich-Poore, G.D.; Martino, C.; Swafford, A.D.; Carroll, T.S.; Kongpachith, S.; Blum, L.K.; Elliott, S.E.; et al. Oral Mucosal Breaks Trigger Anti-Citrullinated Bacterial and Human Protein Antibody Responses in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabq8476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayouni Rad, A.; Pourjafar, H.; Mirzakhani, E. A Comprehensive Review of the Application of Probiotics and Postbiotics in Oral Health. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1120995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmastuti, A.; Hasan, P.N.; Wikandari, R.; Utami, T.; Rahayu, E.S.; Suroto, D.A. Adhesion Properties of Lactobacillus Plantarum Dad-13 and Lactobacillus Plantarum Mut-7 on Sprague Dawley Rat Intestine. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.M.; Teixeira-Santos, R.; Mergulhão, F.J.M.; Gomes, L.C. The Use of Probiotics to Fight Biofilms in Medical Devices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, N.C.; Ramiro, J.M.P.; Quecan, B.X.V.; De Melo Franco, B.D.G. Use of Potential Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Biofilms for the Control of Listeria Monocytogenes, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Escherichia Coli O157:H7 Biofilms Formation. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzegari, A.; Kheyrolahzadeh, K.; Hosseiniyan Khatibi, S.M.; Sharifi, S.; Memar, M.Y.; Zununi Vahed, S. The Battle of Probiotics and Their Derivatives Against Biofilms. IDR 2020, Volume 13, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfa, P.; Brambilla, L.; Giardina, S.; Masciarelli, M.; Squarzanti, D.F.; Carlomagno, F.; Meloni, M. Evaluation of Antimicrobial, Antiadhesive and Co-Aggregation Activity of a Multi-Strain Probiotic Composition against Different Urogenital Pathogens. IJMS 2023, 24, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, G.L.V.; Leite, A.Z.; Higuchi, B.S.; Gonzaga, M.I.; Mariano, V.S. Intestinal Dysbiosis and Probiotic Applications in Autoimmune Diseases. Immunology 2017, 152, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vong, L.; Lorentz, R.J.; Assa, A.; Glogauer, M.; Sherman, P.M. Probiotic Lactobacillus Rhamnosus Inhibits the Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. The Journal of Immunology 2014, 192, 1870–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Luo, X.M. SLE: Another Autoimmune Disorder Influenced by Microbes and Diet? Front. Immunol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Deng, Y.; He, Q.; Yang, K.; Li, J.; Xiang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhu, X.; Chen, H. Safety and Efficacy of Probiotic Supplementation in 8 Types of Inflammatory Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 34 Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 961325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhun, J.; Cho, K.-H.; Lee, D.-H.; Kwon, J.Y.; Woo, J.S.; Kim, J.; Na, H.S.; Park, S.-H.; Kim, S.J.; Cho, M.-L. Oral Administration of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus Ameliorates the Progression of Osteoarthritis by Inhibiting Joint Pain and Inflammation. Cells 2021, 10, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).