Submitted:

25 January 2024

Posted:

26 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.0. Introduction

2.0. Materials and Methods

2.1. C. difficile Strains and Culture

2.2. Porcine Monocyte Isolation and Culture

2.3. Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

2.4. Monocyte Infection Studies

2.5. Measurement of ROS in Monocytes

2.6. Measurement of RNS in Monocytes

2.7. Fluorescence Microscopy

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3.0. Results

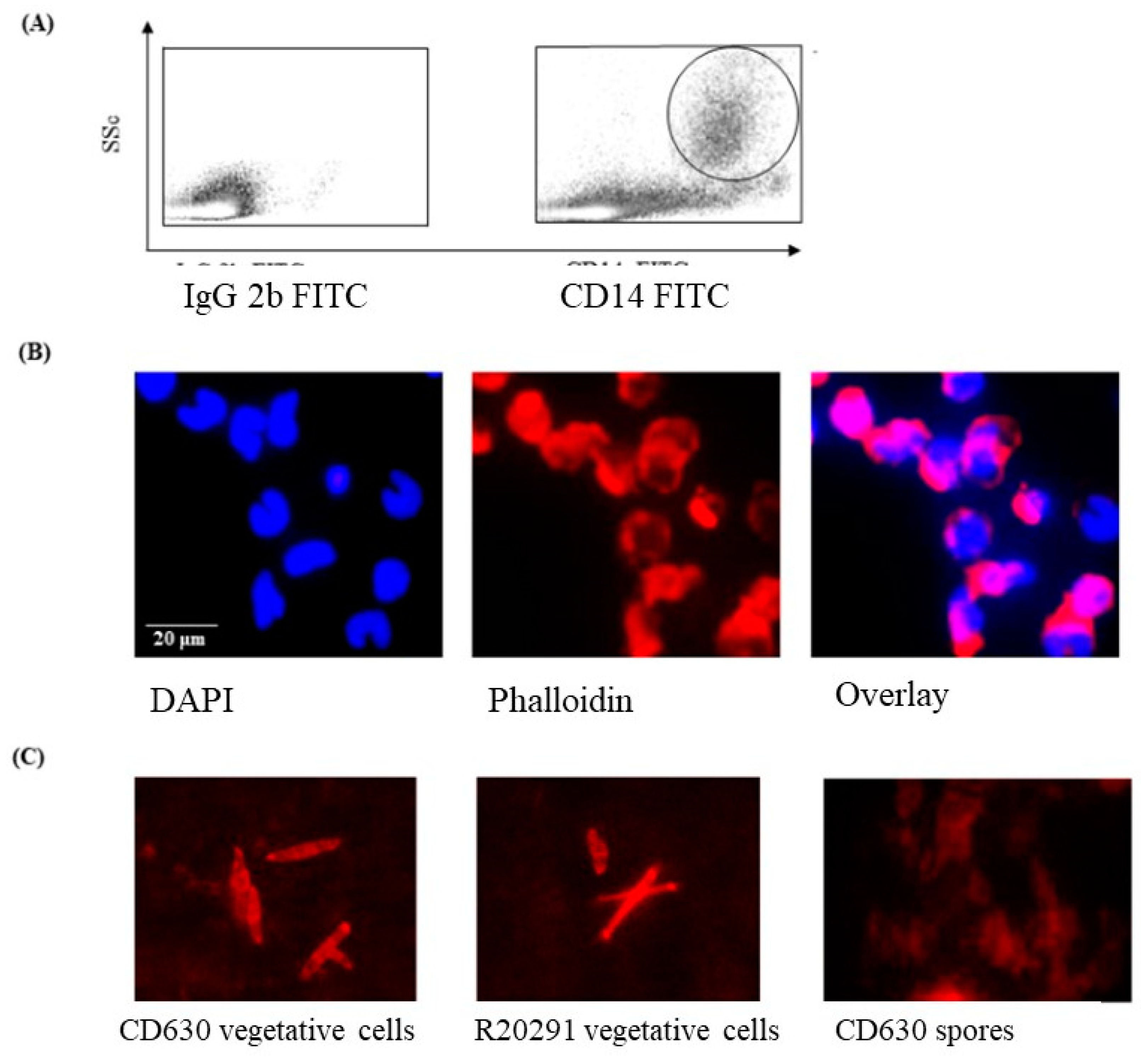

3.1. Phenotype and Morphology of Uninfected (Steady-State) Porcine Monocytes

3.2. Staining of C. difficile Vegetative Cells

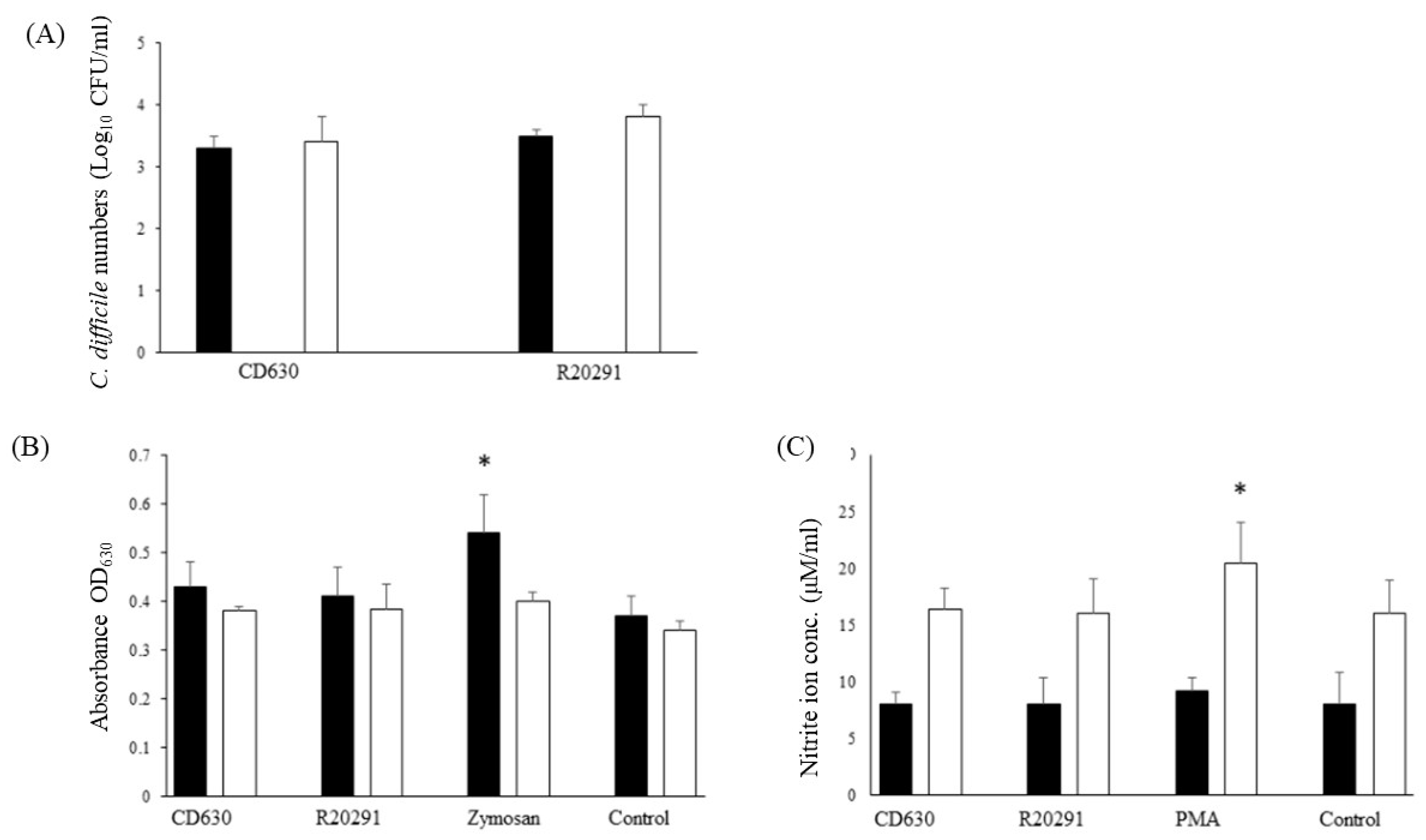

3.3. Survival Dynamics of C. difficile in Porcine Monocytes

3.4. Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species Produced by Porcine Monocytes in Response to C. difficile Infection

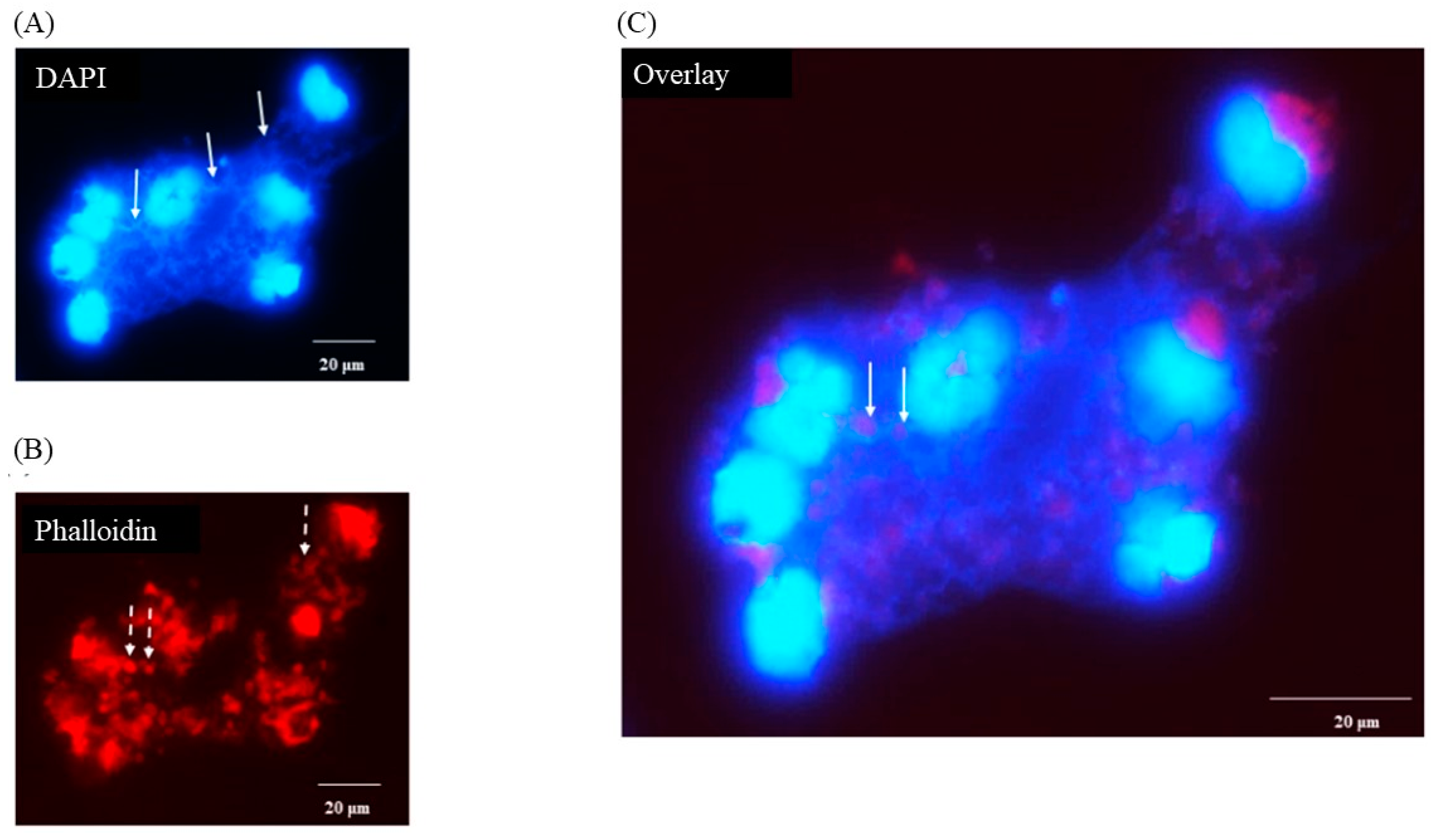

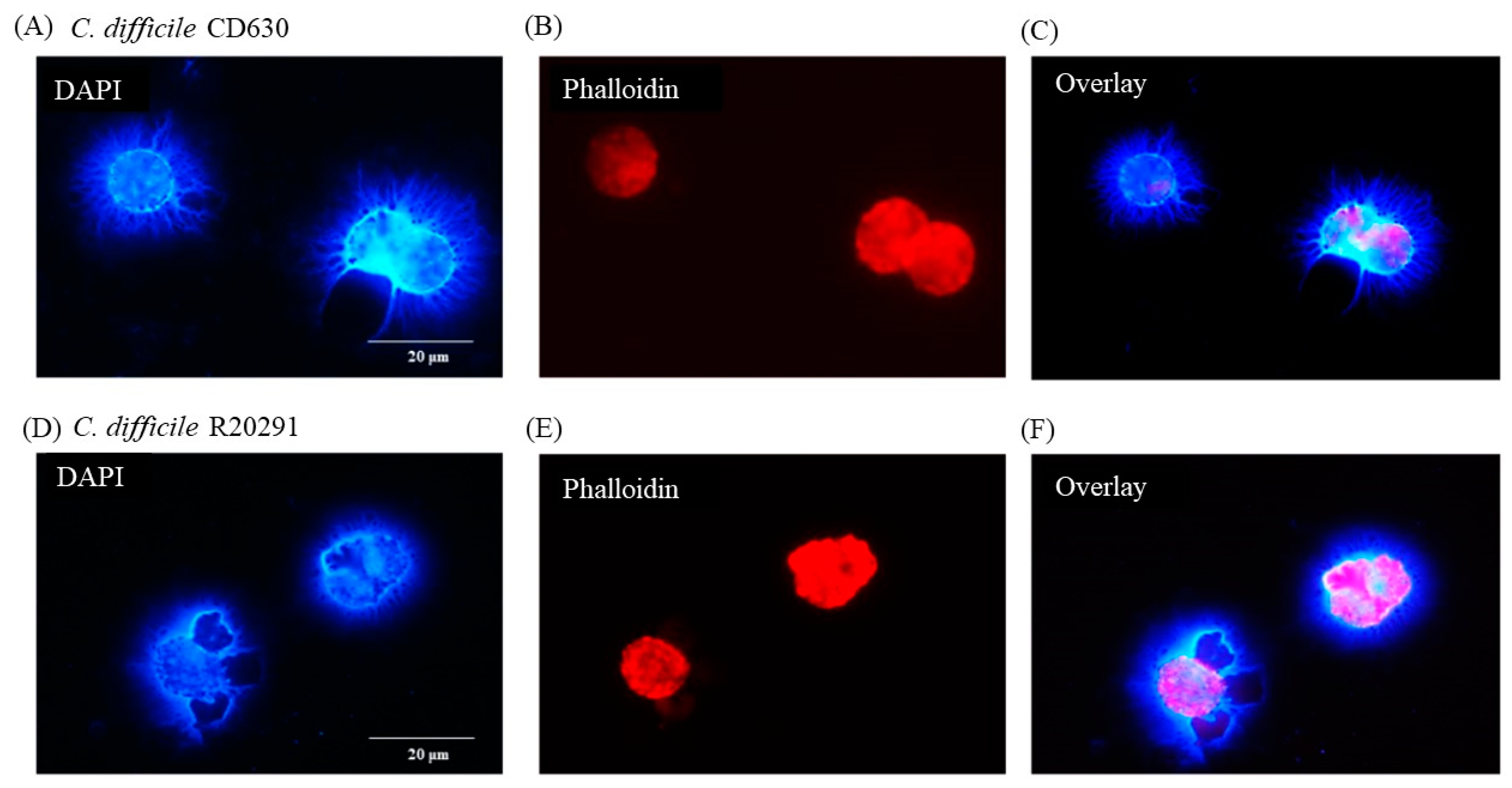

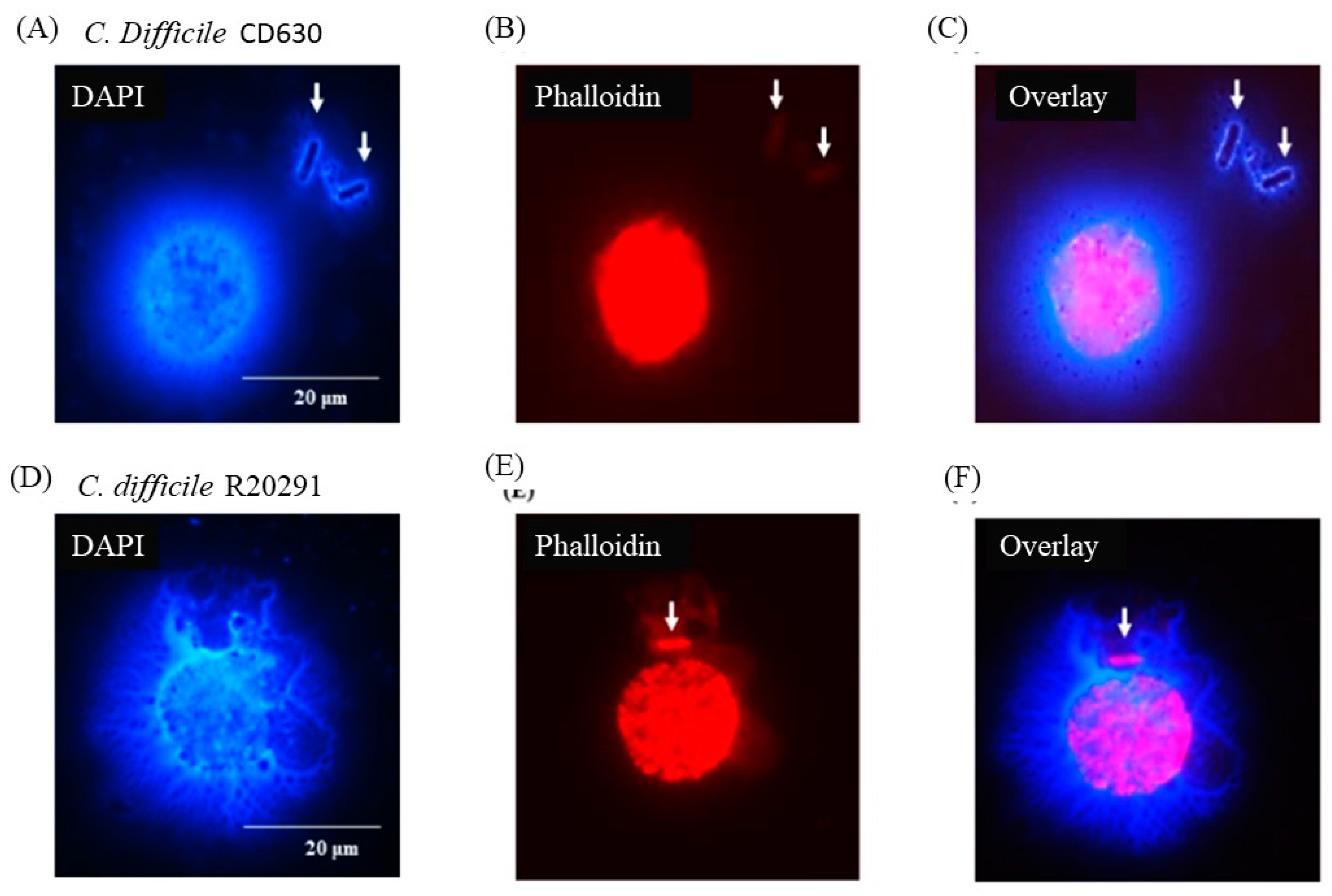

3.5. Porcine Monocyte form DNA Traps to Immobilize C. difficile

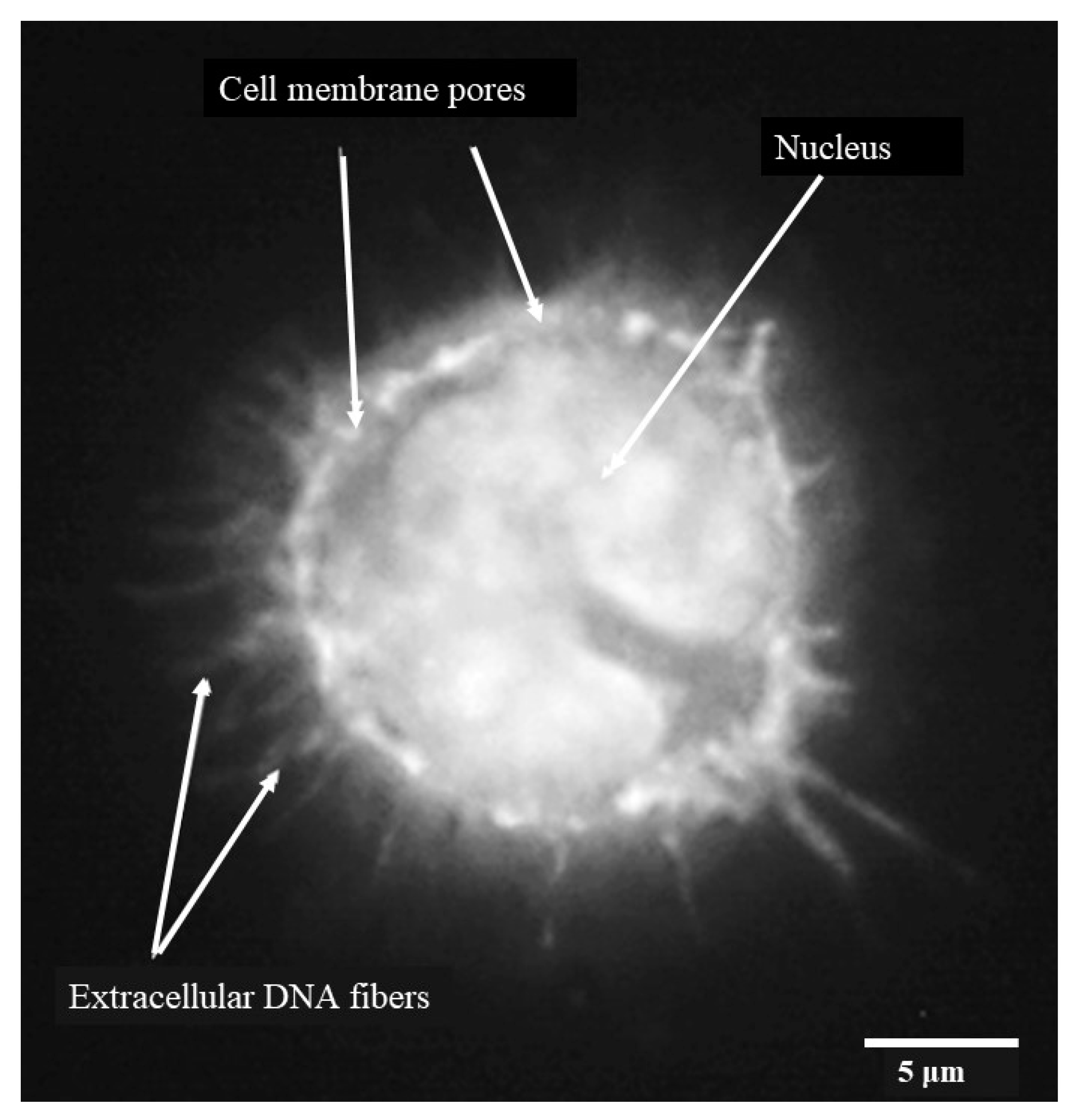

3.6. Following 24 h Culture of Porcine Monocytes with C. difficile, Complete Etosis Occurred but Extracellular DNA Was Still Able to Entrap CD630 or R20291

4.0. Discussion

References

- Songer, J.G. The emergence of Clostridium difficile as a pathogen of food animals. Anim Health Res Rev 2004, 5, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, M.M.; Riley, T.V. Clostridium difficile infection in humans and piglets: a 'One Health' opportunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013, 365, 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Cowardin, C.A.; Petri, W.A., Jr. Host recognition of Clostridium difficile and the innate immune response. Anaerobe 2014, 30, 205–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songer, J.G.; Uzal, F.A. Clostridial enteric infections in pigs. J Vet Diagn Invest 2005, 17, 528–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, A.; Ahrens, R.; Steinbrecher, K.; et al. Colonic eosinophilic inflammation in experimental colitis is mediated by Ly6C(high) CCR2(+) inflammatory monocyte/macrophage-derived CCL11. J Immunol 2011, 186, 5993–6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Katchar, K.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Nanthakumar, N.; Cheknis, A.; Gerding, D.N.; Kelly, C.P. A mouse model of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadighi Akha, A.A.; Theriot, C.M.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; McDermott, A.J.; Falkowski, N.R.; Tyra, H.M.; Rutkowski, D.T.; Young, V.B.; Huffnagle, G.B. Acute infection of mice with Clostridium difficile leads to eIF2α phosphorylation and pro-survival signalling as part of the mucosal inflammatory response. Immunology 2013, 140, 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarchum, I.; Liu, M.; Shi, C.; Equinda, M.; Pamer, E.G. Critical role for MyD88-mediated neutrophil recruit McDermott, A.J.; Falkowski, N.R.; McDonald, R.A.; et al. Role of interferon-γ and inflammatory monocytes in driving colonic inflammation during acute Clostridium difficile infection in mice. Immunology 2017, 150, 468–477. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, A.J.; Falkowski, N.R.; McDonald, R.A.; et al. Role of interferon-γ and inflammatory monocytes in driving colonic inflammation during acute Clostridium difficile infection in mice. Immunology 2017, 150, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, G.A.C.; Sullivan, G.W.; Cielsa, W.P.; Carper, H.T.; Mandell, G.L.; Guerrant, R.L. Clostridium difficile Toxin A alters in vitro-adherent neutrophil morphology and function. J Infect Dis 2002, 185, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keessen, E.C.; Harmanus, C.; Dohmen, W.; Kuijper, E.J.; Lipman, L.J. Clostridium difficile infection associated with pig farms. Emerg Infect Dis 2013, 19, 1032–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goorhuis, A.; Bakker, D.; Corver, J.; Debast, S.B.; Harmanus, C.; Notermans, D.W.; Bergwerff, A.A.; Dekker, F.W.; Kuijper, E.J. Emergence of Clostridium difficile infection due to a new hypervirulent strain, polymerase chain reaction ribotype 078. Clin Infect Dis 2008, 47, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, L.F.; Donahue, E.H.; Cartman, S.T.; Barton, R.H.; Bundy, J.; McNerney, R.; Minotn, N.P.; Wren, B.W. The analysis of para-cresol production and tolerance in Clostridium difficile 027 and 012 strains. BMC Microbiol 2011, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, D.A.; Minton, N.P. Sporulation studies in Clostridium difficile. J Microbiol Methods 2011, 87, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Askar, B.; Hulme, S.; Neilson, P.; Barrow, P.; Foster, N. Differential Immune Phenotypes in Human Monocytes Induced by Non-Host-Adapted Salmonella enterica Serovar Choleraesuis and Host-Adapted S. Typhimurium. Infect Immun 2018, 86, e00509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.H.; Fikrig, S.M.; Smithwick, E.M. Infection and nitroblue-tetrazolium reduction by neutrophils. A diagnostic acid. Lancet ii 1968, 2, 532–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutamba, S.; Allison, A.; Barrow, P.A.; Mahida, Y.; Foster, N. Expression of IL-1Rrp2 by human myelomonocytic cells is unique to DCs and facilitates DC maturation by IL-1F8 and IL-1F9. European J Immunol 2012, 42, 607–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penha, R.; Higgins, J.; Mutamba, S.; Barrow, P.; Mahida, Y.; Foster, N. IL-36 receptor is expressed by human blood and intestinal T lymphocytes and is dose-dependently activated via IL-36β and induces CD4+ lymphocyte proliferation. Cytokine. 2016, 85, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; Fauler, B.; Uhlemann, Y.; Weiss, D.S.; Weinrauch, Y.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yipp, B.G.; Kubes, P. NETosis: how vital is it? Blood 2013, 122, 2784–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboe, D.M.; Curtis, B.J.; Chen, M.M.; Ippolito, J.A.; Kovacs, E.J. Extracellular traps and macrophages: new roles for the versatile phagocyte. J Leukoc Biol 2015, 97, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loures, F.V.; Rohm, M.; Lee, C.K.; Santos, E.; Wang, J.P.; Specht, C.A.; Calich, V.L.G.; Urban, C.F.; Levitz, C.F. Recognition of Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells is mediated by dectin-2 and results in formation of extracellular traps. PLoS Pathog 2015, 11, e1004643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, B.E.; Grinstein, S. Unconventional roles of the NADPH oxidase: signaling, ion homeostasis, and cell death. Sci STKE 2007, 379, pe11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staerck, C.; Gastebois, A.; Vandeputte, P.; Calenda, A.; Larcher, G.; Gillmann, L.; Papon, N.; Bouchara, J.P.; Fleury, M.J.J. Microbial antioxidant defense enzymes. Microb Pathog 2017, 110, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryden, M.; Cooke, J.; Salib, R.; Holding, R.; Pender, S.L.F.; Brooks, J. Hot topics in reactive oxygen therapy: Antimicrobial and immunological mechanisms, safety and clinical applications. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2017, 8, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryden, M. Reactive oxygen species: a novel antimicrobial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2018, 51, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, S.J.; Daigneault, M.; Bewley, M.A.; Preston, J.A.; Marriott, H.M.; Walmsley, S.R.; Read, R.C.; Whyte, M.K.B. Distinct cell death programs in monocytes regulate innate responses following challenge with common causes of invasive bacterial disease. J Immunol 2010, 185, 2968–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassoe, C.F.; Smith, I.; Sørnes, S.; Halstensen, A.; Lehmann, A.K. (2000) Concurrent measurement of antigen- and antibody-dependent oxidative burst and phagocytosis in monocytes and neutrophils. Methods 2000, 21, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarchum, I.; Liu, M.; Shi, C.; Equinda, M.; Pamer, E.G. Critical role for MyD88-mediated neutrophil recruitment during Clostridium difficile colitis. Infect Immun 2012, 80, 2989–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).