1. Introduction

A mayor review, originated from the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death, described 12 different types of cell death, which include intrinsic apoptosis, extrinsic apoptosis, membrane permeability transition (MPT)-dependent necrosis, necroptosis, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, parthanatos, entotic cell death, NETotic cell death, lysosome-dependent cell death, autophagy-dependent cell death, and immunogenic cell death [

1]. Within these cell death processes ferroptosis stands out, with over 4000 publications during year 2023 alone.

Ferroptosis is a cell death process characterized by the accumulation of lipid peroxides in a manner that is dependent on cellular iron content [

2,

3]. Its importance, and the recent attention it has received, is related to the participation of ferroptosis in some of the most relevant of today pathologies, such as cancer and neurodegeneration [

4,

5]. Lately, the use of ferroptosis as a cell killing mechanism has brought about new strategies for the treatment of various malignant diseases [

6].

The initial characterization of ferroptosis began in the context of a study using high throughput screening to search for molecules with anti-cancer activity [

7]; among other agents, erastin was found to produce non-apoptotic cell death much more efficiently in cells with the active RAS oncogene. Later insights into the effects of erastin determined its binding to mitochondrial voltage-gated anion channels (VDACs) [

8] and excluded canonical cell death mechanisms, such as apoptosis, autophagic death, and necroptosis. Erastin-induced death is morphologically different from the classic types of cell death; it involves neither nuclear fragmentation nor vacuolization and it entails reduction of cytoplasmic size, mitochondrial swelling, and plasma membrane rupture [

8,

9].

After these first studies, other compounds were found that induce the same type of cell death, with identical morphological characteristics and insensitivity to inhibitors, among others; the most notable among them was RSL3 [

3]. Erastin and RSL3 induce a type of death with oxidative characteristics, which depends on iron, and it is characterized by the accumulation of lipid peroxides [

9]. In particular, erastin, in addition of binding to VDAC channels, blocks the cystine/glutamate exchanger xCT, which leads to cellular glutathione (GSH) depletion [

2,

10]. This decrease in cellular GSH content leads to an oxidative imbalance that, among other factors, results in inhibition of GPx4, which is the key enzyme that catalyzes the neutralization of membrane lipid peroxides to their respective alcohols. In contrast, RSL3 directly inhibits GPx4, resulting in the same accumulation of lipid peroxides but without decreasing GSH concentration [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Of note is the relationship between the inhibition of GPx4 and increased ROS production. A mediator between these two landmarks of ferroptosis is the pro-apoptotic protein Bid [

15]; based on the observation that Bid inhibition preserves cell viability in RSL3-treated cells, the authors propose a sequence of events in which GPx4 inhibition enhances 12/15 LOX activity, which results in lipid peroxide formation and BID transactivation. In turn, activated Bid binds to mitochondria, decreasing their membrane potential and increasing ROS production [

15]. Some research groups consider that ferroptosis is equivalent to oxytosis, a type of cell death described in hippocampal neurons [

16], which was previously reported as a form of glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity [

10]. In oxytosis, cell death may be initiated in a way similar to ferroptosis; that is, by blocking the xCT system. Since the xCT system is an exchanger-type co-transporter that uses the glutamate gradient to allow for cystine entry, when glutamate is present in excess (>5 mM) in the extracellular medium, it stops this gradient and inhibits cystine entrance. Since cystine is a GSH precursor, GSH concentrations decrease, which results in LOX activation, ROS generation, lipid peroxidation and cell death. Death occurs in the absence of caspase activation, and there is protection by iron chelators. However, unlike what has been reported for ferroptosis, the execution of oxytosis depends on the massive influx of calcium from the extracellular medium [

17]. The resulting intracellular calcium increase affects the mitochondria, producing the release of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), which can then translocate to the nucleus [

18].

The role of calcium in ferroptosis was dismissed by pioneering studies, due to the lack of protective effects of CoCl

2 and GdCl

3, which are both plasma membrane calcium channels blockers [

19]. A following report in HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells [

2], also dismissed the role of calcium in ferroptosis, arguing that neither the calcium indicator fura-2 nor intracellular calcium chelation with BAPTA-AM showed protection. In contrast, Maher's group proposed the hypothesis that ferroptosis and oxytosis are the same phenomenon, reporting the protective effect of CoCl

2 against RSL3- and erastin-induced cell death, in a manner analogous to that classically shown for oxytosis [

20,

21]. In the same line, protective effects of the calcium chelator BAPTA and of CoCl

2 against erastin-induced cell death have been reported in HT22 and LUHMES [

22].

Ferroptosis is accompanied by increased ROS levels; interestingly, many components that regulate intracellular calcium levels are stimulated by ROS, including the ER-resident calcium channels IP

3R and RyR [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Thus, it is conceivable that the resulting calcium increase, originated from ROS-stimulated calcium release from the ER, could contribute to ferroptosis. In this line, a recent work reported that suppression of calcium release mediated by RyR channels, through the use of inhibitory concentrations of ryanodine, offers significant but partial protections against RSL3-induced cell death in hippocampal neurons [

27]. However, a putative role of IP

3R-mediated calcium release in ferroptosis is unknown. Given this background, the role of calcium in ferroptosis is clearly a matter of debate and may have nuances that depend on the cell system studied.

Here, we explored the hypothesis that in human neuroblastoma cells that do not express RyR channels, inhibition of the GPx4 enzyme activates IP3R-mediated calcium release which results in increased cytoplasmic and mitochondrial calcium levels that contribute to the development of ferroptotic cell death.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture.

SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC, CRL-2266) were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in DMEM/F12 media (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PenStrep (Gibco). For experiments, 80% confluence cultures were used.

2.2. Cell viability.

Viability was assessed with the Vybrant® MTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (V-13154; Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Alternatively, cells were tested for propidium iodide (PI) permeability by incubation for 15 minutes (min) with 1 mg/ml of the fluorescence marker PI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in modified Krebs buffer. Afterwards, PI red fluorescence was detected in random fields with a Nikon TMS epifluorescence microscope.

2.3. Cell morphology.

After RSL3 treatment, cells were washed with modified Krebs buffer and imaged in a phase contrast Nikon microscope. Subsequently, images were segmented using ImageJ creating binary masks. From the resulting segmentation images, cell area, perimeter and circularity (a measure of roundedness) were determined.

2.4. IP3R1 down-regulation and mitochondrial calcium detection.

Cover-glass grown cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and DNA at a 1:3 ratio. Cells were incubated for 6 hours with the Lipofectamine/DNA complex. For IP3R1 down-regulation, cells were transfected with PTRIPZ (Dharmacon) carrying a shRNA sequence against the type-1 IP3R (IP3R1) isoform and a red fluorescent (RFP) reporter sequence. Forty-eight hours after transfection with PTRIPZ, cells were challenged with RSL3 (5 µM, 4 h) and intracellular calcium was determined as described below. After calcium recording, cells were imaged to individualize transfected cells and their morphology, including their roundness degrees.

For mitochondrial calcium sensing, cells were transfected with the plasmid pCMV CEPIA2mt (Addgene), carrying the mitochondrial calcium sensor Cepia2 [

28]. Similarly, mitochondrial calcium levels in pCMV CEPIA2mt-transfected cells were determined 48 h after transfection.

2.5. Western Blot Analysis.

After the corresponding treatments, SH-SY5Y cells were treated for 15 min with Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) lysis buffer supplemented with proteinase inhibitors (Roche Life Science Products). After centrifugation, supernatants were collected, analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and samples were wet transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blotted overnight at 4°C using the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-IP

3R1 (1/1000, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-β-actin (1/5000, Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-cleaved Caspase-3 (1/1000, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-Bcl-2 (1/1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For the detection of RyR channels, Western Blot analysis of SH-SY5Y cells was performed as previously described [

29]. Samples were separated by electrophoresis in 3.5-8% Tris-Acetate gels; gels were immersed in Tris-Tricine buffer and run for the first hour at 80 mV and then for the following 2 h at 100 mV. The protein bands were transferred to PDVF membranes (Millipore Corp.) and were incubated for 1 h at room temperature using as blocking solution Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 5% fat-free milk for RyR2 and IP

3R detection, or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for RyR1 and RyR3 detection. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking buffers with specific primary antibodies anti-RyR1 (1:500, generously provided by Dr. Vincenzo Sorrentino), anti-RyR2 (1:3000, MA3916, Invitrogen), anti-RyR3 (1:2000, ab9082, Sigma Aldrich) and anti-IP

3R (1:2500, PA1-901, ThermoFisher Scientific). Membranes were washed with saline and were then incubated for 2 h at room temperature with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG antibodies coupled to radish peroxidase (1/5000, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Image acquisition was performed with the Image Lab software, Chemidoc TM MP System (Bio-Rad).

2.6. ROS detection.

The production of ROS was detected by incubation of cells with 5 µM H2DCFDA (ThermoFisher Sci.), which emits fluorescence when oxidized to dichlorofluorescein (DCF) [

30]. A not often recognized fact is that DHDCF is a highly selective hydroxyl radical sensor [

31].

2.7. Calcium change recordings.

For fura-2-based cytoplasmic calcium determinations, cells were loaded for 30 min with 3 µM fura-2-AM in modified Krebs buffer at 37°C. Afterwards cells were washed twice with PBS and were kept in dark for 10 min before starting the recordings. The emitted fluorescence at 510 nm was recorded in a fluorimeter, alternating the excitation between 340 and 380 nm. Recordings lasted 6 min, where the first 2 min corresponded to basal fluorescence determination. Then 0.01% Triton X-100 was added in order to permeabilize the cell membrane and saturate the probe, and the record was continued for additional 2 min. Finally, 50 mM EGTA was added to determine the fluorescence of the calcium-unbound probe. Calcium concentrations were calculated using the Grynkiewicz equation [

32]:

Where Kd = 145 nM is for fura-2 at 20 C° [

33]; R is the ratio between the fluorescence produced by the excitation at 340 nm (bound) and 380 nm (unbound); R

max corresponds to the fluorescence ratio emitted by the calcium-saturated probe (after Triton X-100 treatment) and R

min is the ratio of fluorescence emitted by the calcium depleted probe (EGTA); Sfb is the ratio of the fluorescence recorded at 380 (unbound probe) after Triton-X-100 and EGTA additions [

34].

For fluo-3 based calcium imaging, cells were loaded for 30 min with 5 µM fluo-3-AM in modified Krebs buffer at 37°C. Then cells were washed twice with PBS and let to rest for 10 min before recordings. Recordings were performed in a LSM 710 Zeiss confocal microscope using the 488 nm laser for fluo-3 excitation. Setup configuration was kept constant for every condition in each experiment.

2.8. Lipid peroxidation.

To assess lipid peroxidation after RSL3 treatment, cells were loaded with 5 µM BODIPY C11 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C for 30 min. Then, cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed for 15 min with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. Subsequently, cells were washed three times with PBS and were mounted in microscope slides to be imaged in a LSM 710 Zeiss confocal microscope.

For detection of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE)-protein adducts, cells were fixed with 4% PFA, followed by a permeabilization with 0.1% Triton-X-100 for 30 min and blocked with 4% BSA for 30 min. Cells were incubated with anti-HNE (1/400, Abcam) at 4°C overnight, washed three times with PBS and incubated with an Alexa 488 anti-mouse secondary antibody (1/400, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were washed 2 times with PBS and mounted in microscope slides to be imaged in a LSM 710 Zeiss confocal microscope.

2.9. Statistical analysis.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine the normal distribution of replicates. For the comparison of multiple experimental conditions, One-way ANOVA was used to test for differences in mean values, and Dunnett’s post-hoc test was used for comparisons between mean values. For the comparison of two experimental conditions, the unpaired two-tail Student t test was used to compare differences between mean values. A P value <0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

4. Discussion

The participation of calcium in ferroptosis is a matter of debate. Initial studies using HT-1080 epithelial cells discarded a role for calcium under the observation that ferroptosis was not blocked by the extracellular calcium chelator EGTA or by the intracellular chelator BAPTA-AM [

2]. Nonetheless, other reports proposed that ferroptosis and oxytosis are the same phenomenon [

20,

21]. Because oxytosis is highly dependent on calcium entry into the cell, here we evaluated the participation of calcium in a model of RSL3-induced ferroptosis using the dopaminergic cell line SH-SY5Y. Of note, this is the first report that establishes a firm link between calcium and ferroptosis in this neuroblastoma cell line. In addition to previous works, which reported that plasma membrane calcium channels [

21,

41] or RyR channels [

27,

41] act as mediators in the increase of intracellular calcium induced by RSL3, here we additionally identified IP

3R channels as mediators of the calcium increase induced by RSL3.

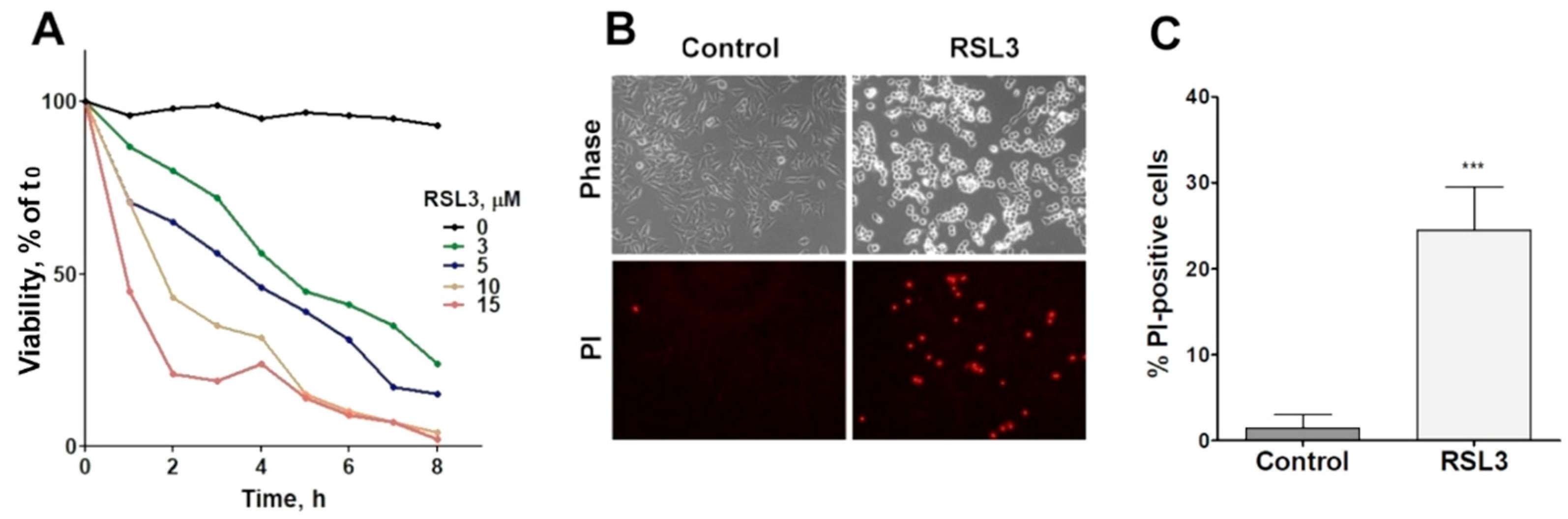

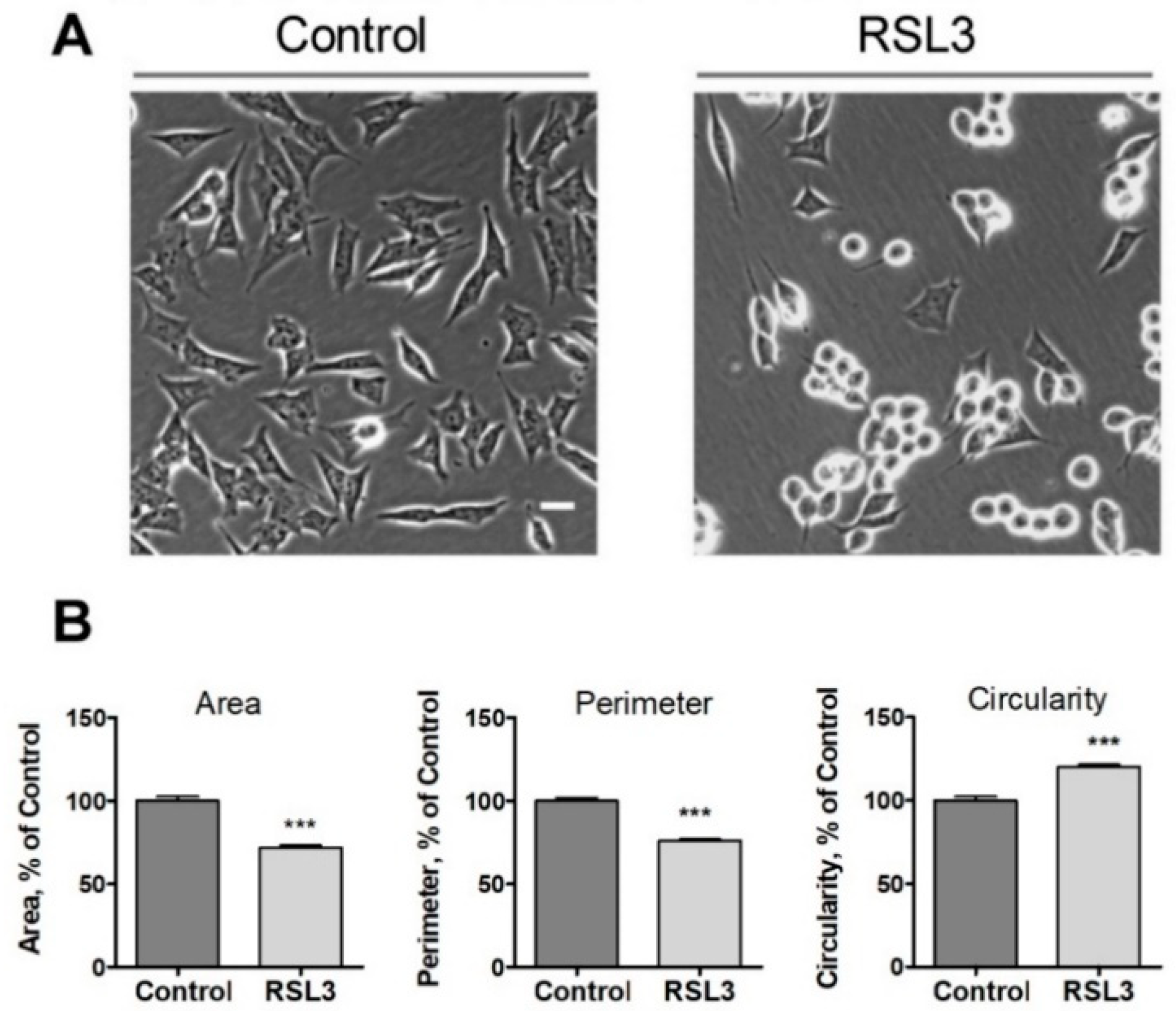

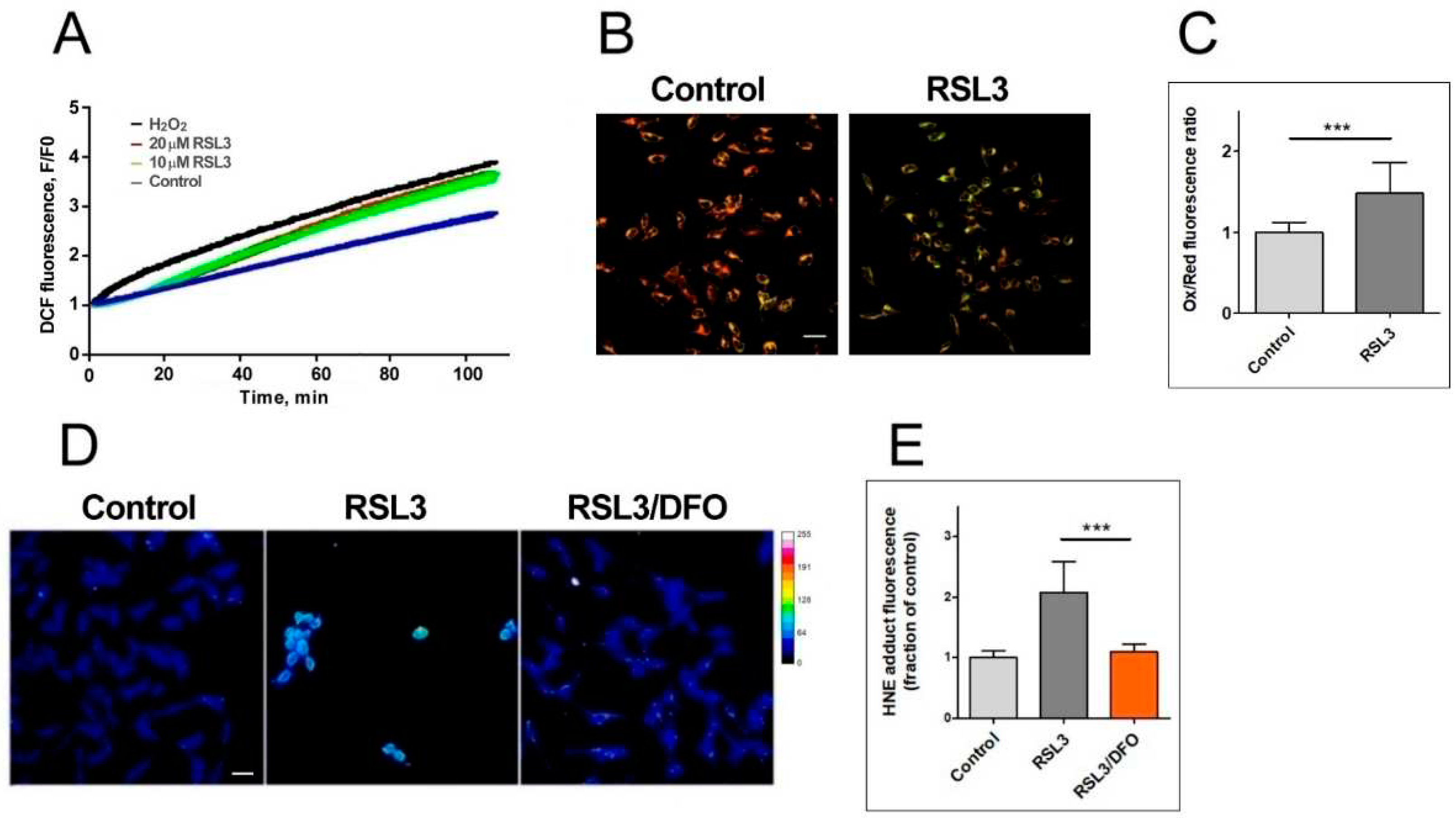

We found that RSL3 affected the viability of SH-SY5Y cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Thus, RSL3 induced 50% cell death at times as short as 4 h. Treatment with RSL3 also induced landmarks of ferroptosis, such as an increase in ROS levels and a remarkable change in cell morphology, with a significant increase in cell roundness. Arguably, the changes in ROS production and cell morphology are a preamble to cell death. Albeit the direct inhibitory effects of RSL3 as an inhibitor of GPx4 have been recently questioned based on studies performed in cell-free systems [

42], our results support the role of RSL3 as an effective ferroptosis inducing agent.

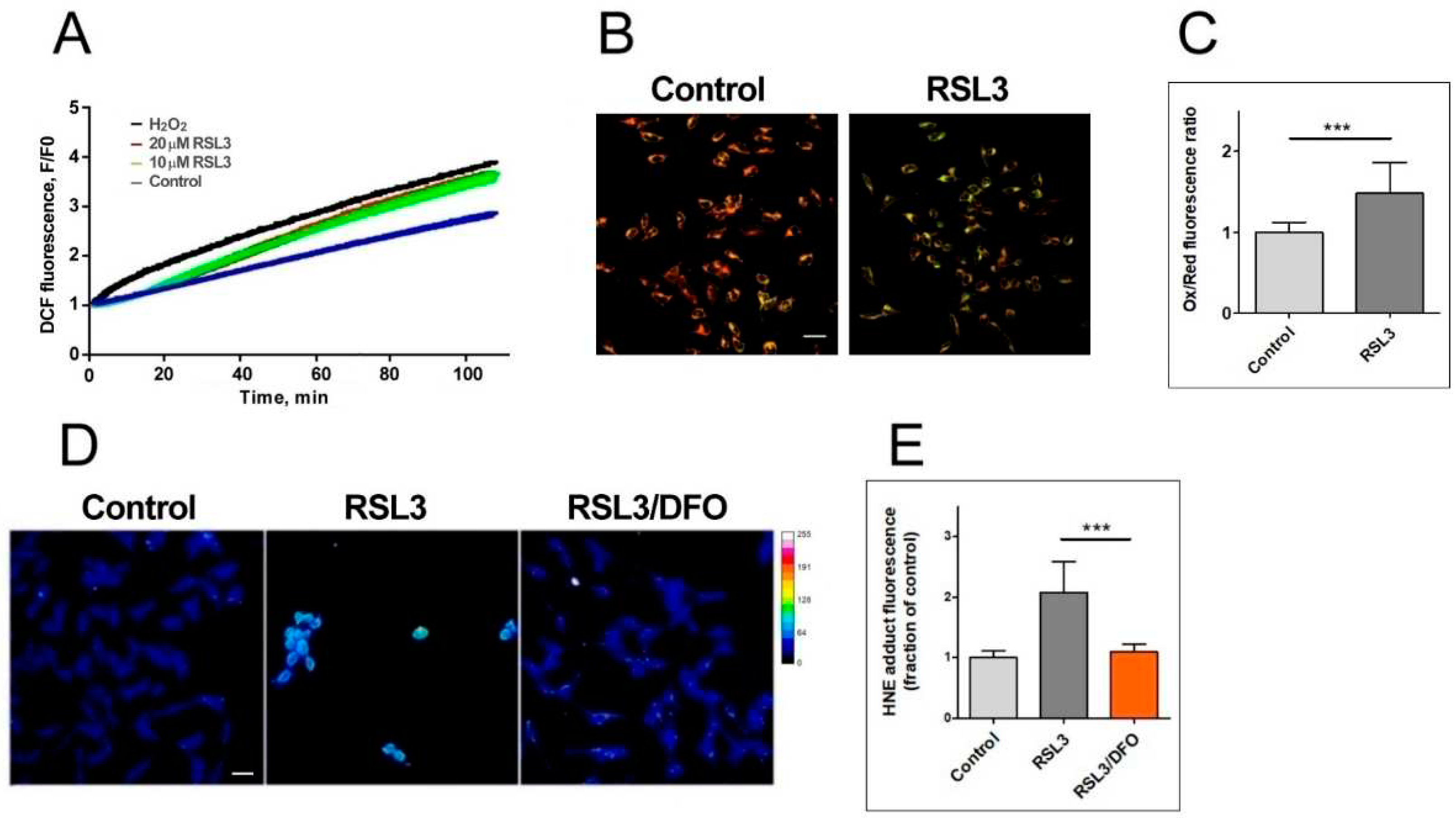

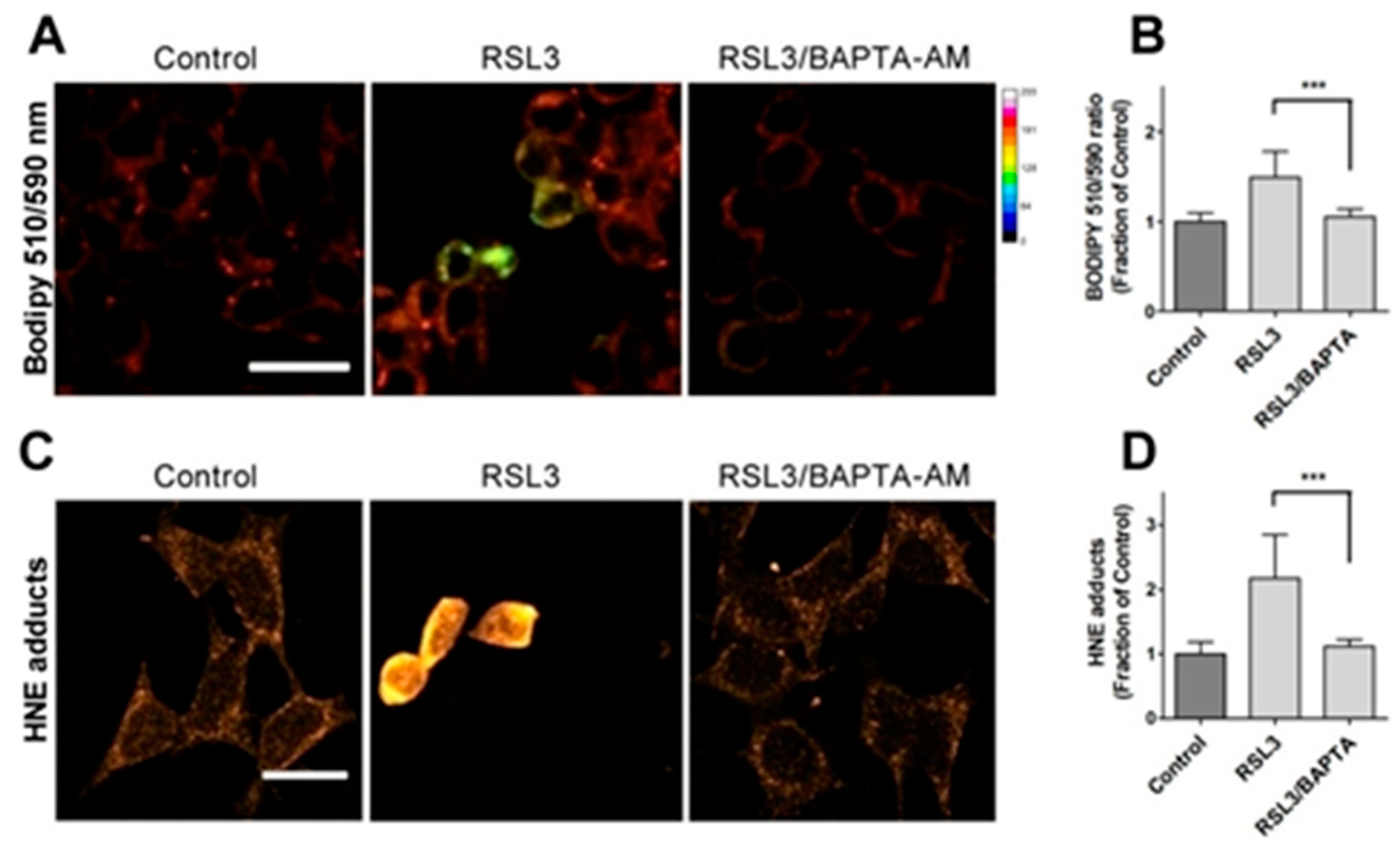

Associated to ROS production there was an increase in membrane lipid peroxidation, a hallmark of ferroptosis. In accordance with the participation of iron in ferroptosis, co-incubation with the iron chelator DFO precluded lipid peroxidation, as detected by the levels of 4-HNE-protein adducts. Overall, these results indicate that RSL3 induces a robust ferroptotic response in SH-SY5Y cells.

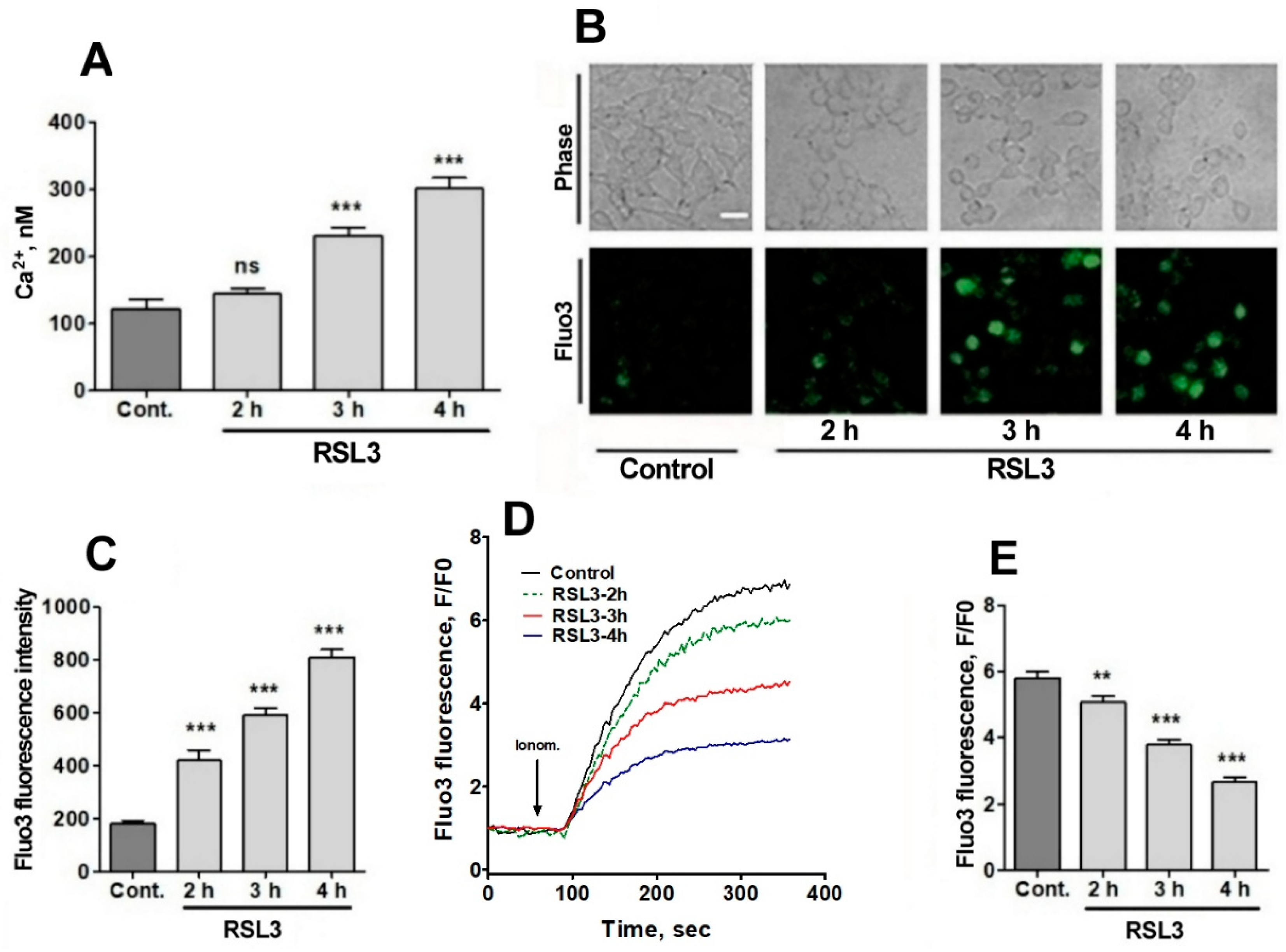

In consideration of a putative participation of calcium in ferroptosis, we used fluorescent probes to detect possible alterations in calcium levels produced by RSL3. Firstly, we observed that the application of RSL3 did not trigger an immediate (seconds-minutes) increase in intracellular calcium concentration in the way that, for example, thapsigargin, carbachol, or even hydrogen peroxide do it in N2a cells and primary hippocampal neurons [

43]. However, examining at later times (above 1 h), we identified a gradual increase in intracellular calcium. A similar observation was reported for hippocampal cells in primary culture [

27]. Using fura-2, we calculated that the basal calcium concentrations of around 100 nM, a value relatively consistent to that reported in the literature for these cells [

44] increased to 300 nM after RSL3 treatments. These calcium concentrations are not particularly high when compared to the increases generated by the calcium ionophore ionomycin (≥ 500 nM). However, their maintenance over time could have consequences for cellular homeostasis.

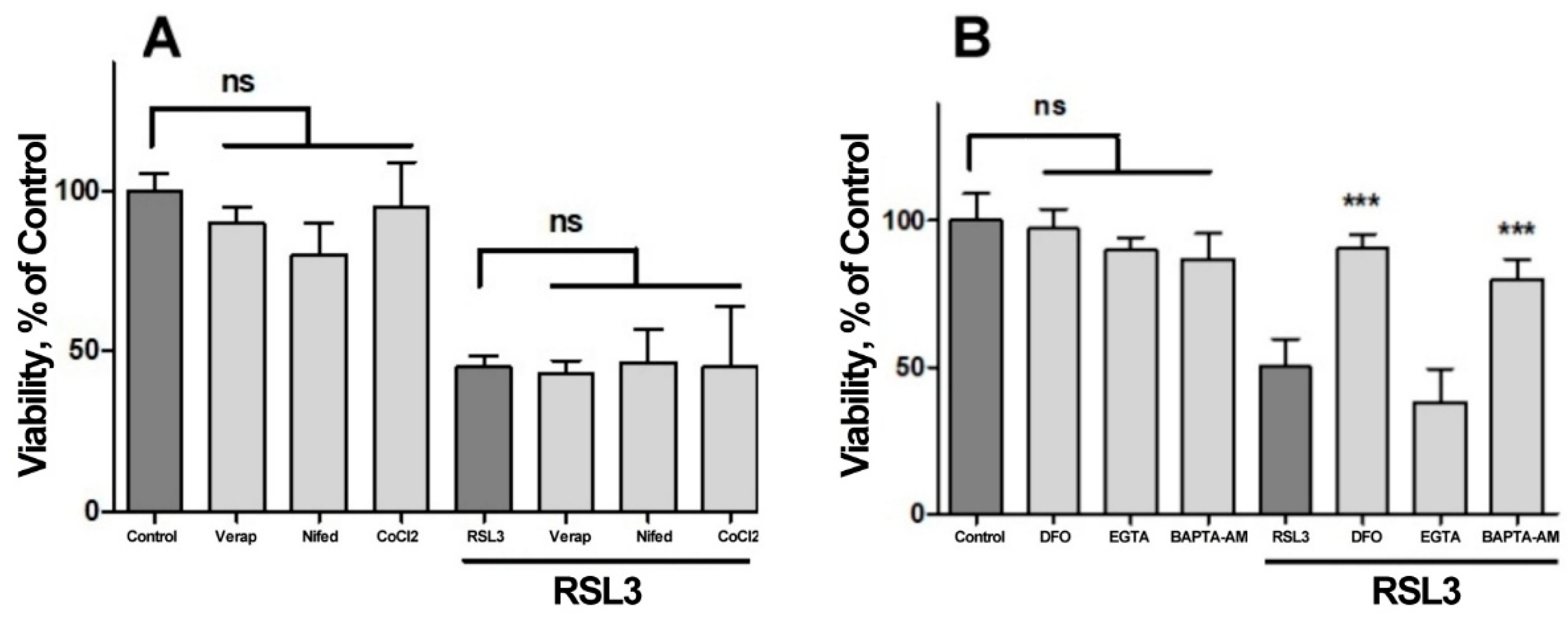

An observation of interest was that the intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA-AM had a protective effect against RSL3 treatment. This protection was not observed in RSL3-treated cells incubated in a medium containing the extracellular calcium chelator EGTA or plasma membrane-resident calcium channels inhibitors. We conclude that, at difference with oxytosis, in the SH-SY5Y cell ferroptosis model the increase in calcium levels induced by RSL3 has an intracellular origin.

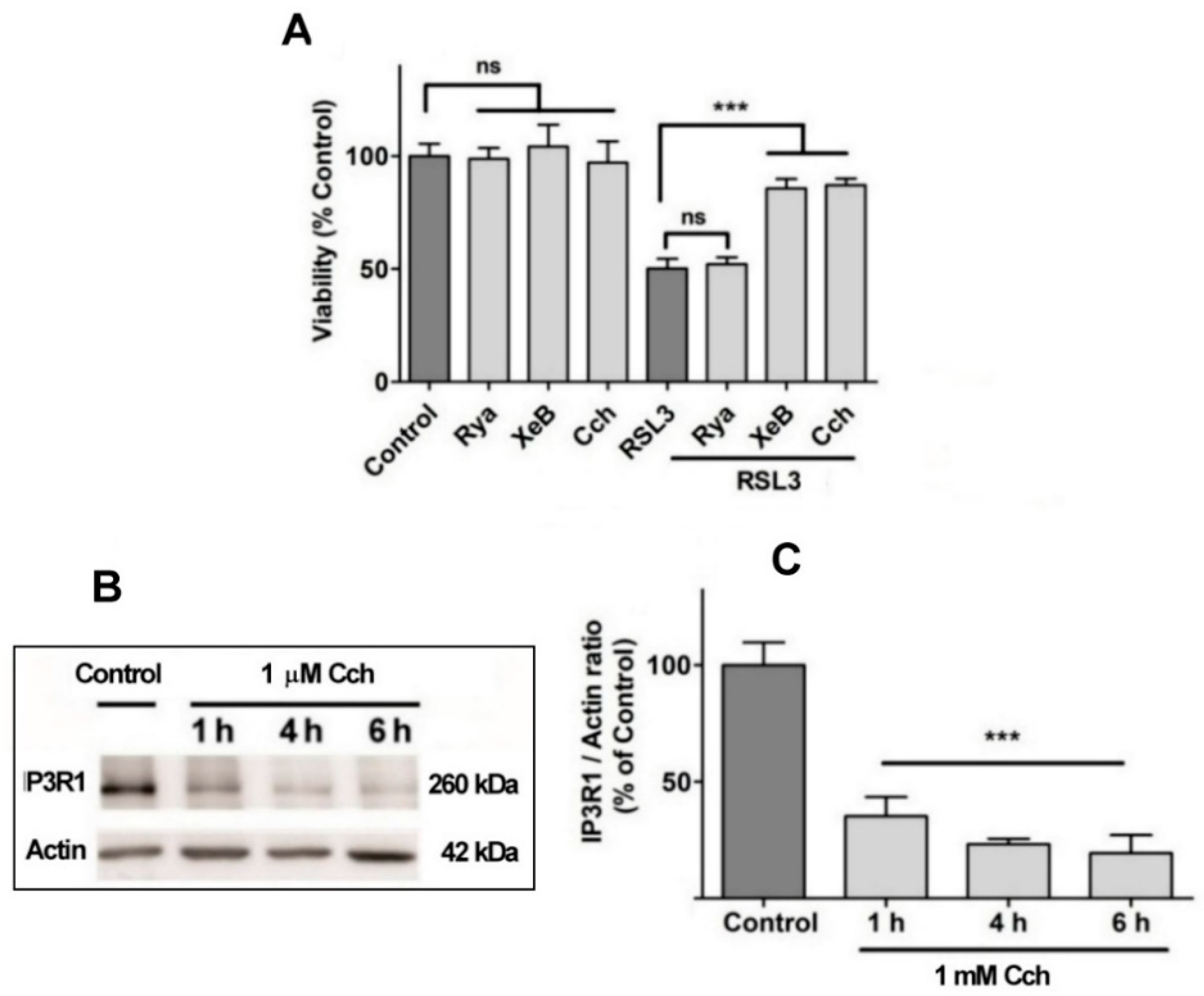

Considering that the most prominent intracellular calcium reservoir corresponds to the ER [

45], we evaluated the possible protective effect of inhibitors of the main channels that allow calcium efflux in the ER, the RyR and the IP

3R calcium channels. We found that xestospongin B, an inhibitor of IP

3R channels, but not ryanodine, an inhibitor of RyR channels, protected against RSL3-induced cell death in viability assays. The lack of effect of ryanodine agrees with the absence of RyR channels reported here for these cells, and with previous reports that found no or very little RyR protein expression in SH-SY5Y cells, albeit RyR mRNA expression was detected [

46,

47,

48]. Notwithstanding, inhibitory concentrations of ryanodine partially protected primary hippocampal neurons against RSL3-induced death [

27]. Thus, calcium release from the ER participates in two different neuronal models of ferroptotic death.

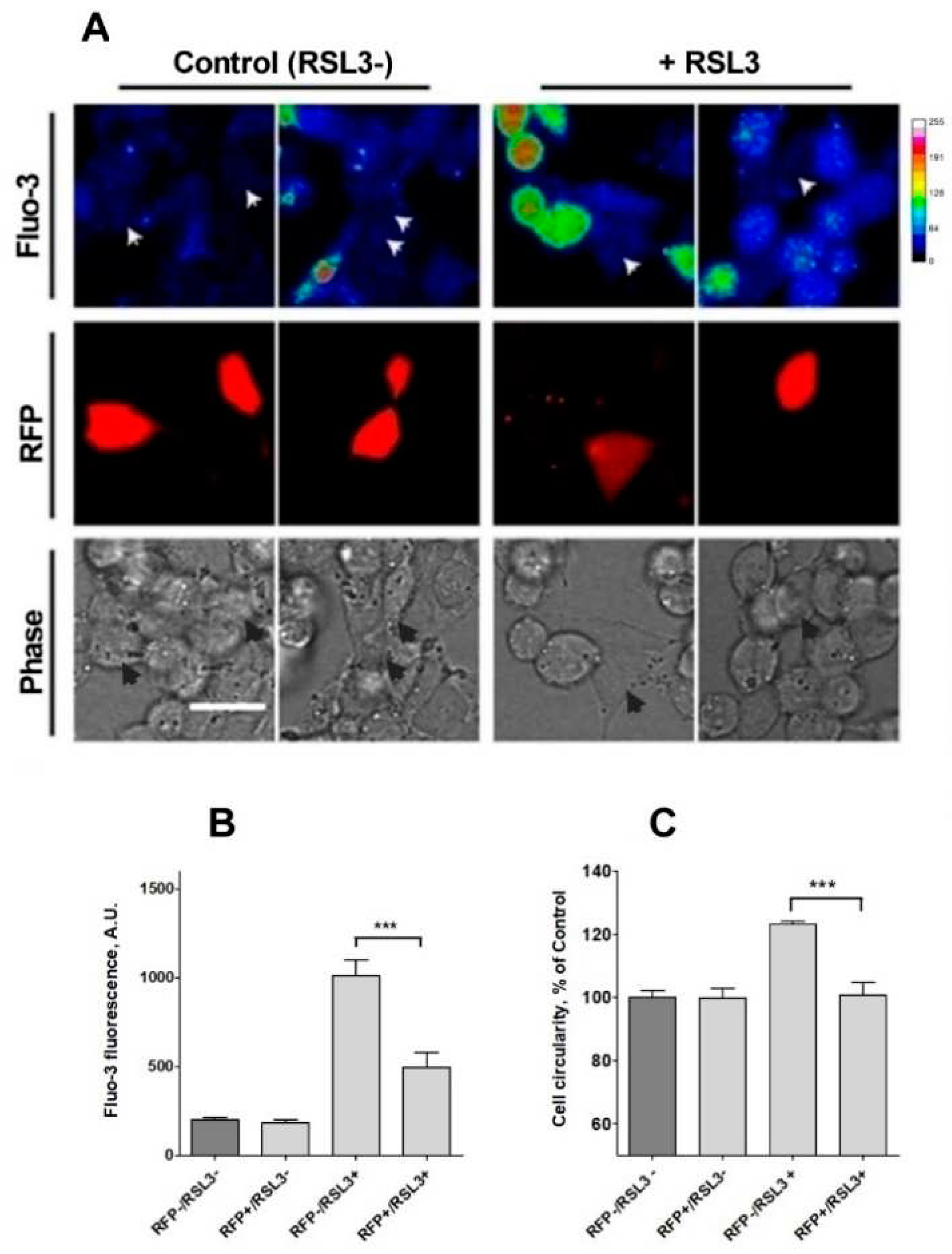

We found that preincubation with carbachol, which produces a decrease in IP

3R protein levels [

38], also exerts protection against the calcium concentration increase produced by RSL3, suggesting that IP

3R channels mediate this increase. In the same vein, cells transfected with an interfering construct for IP

3R1, the isoform mostly expressed in this cell line [

49], presented lower calcium increases after RSL3 treatment, which is consistent with the participation of IP

3R1 in this calcium increase. In addition, transfected cells did not undergo the morphology changes induced by RSL3, an indication that these cells are resistant to RSL3-induced ferroptosis.

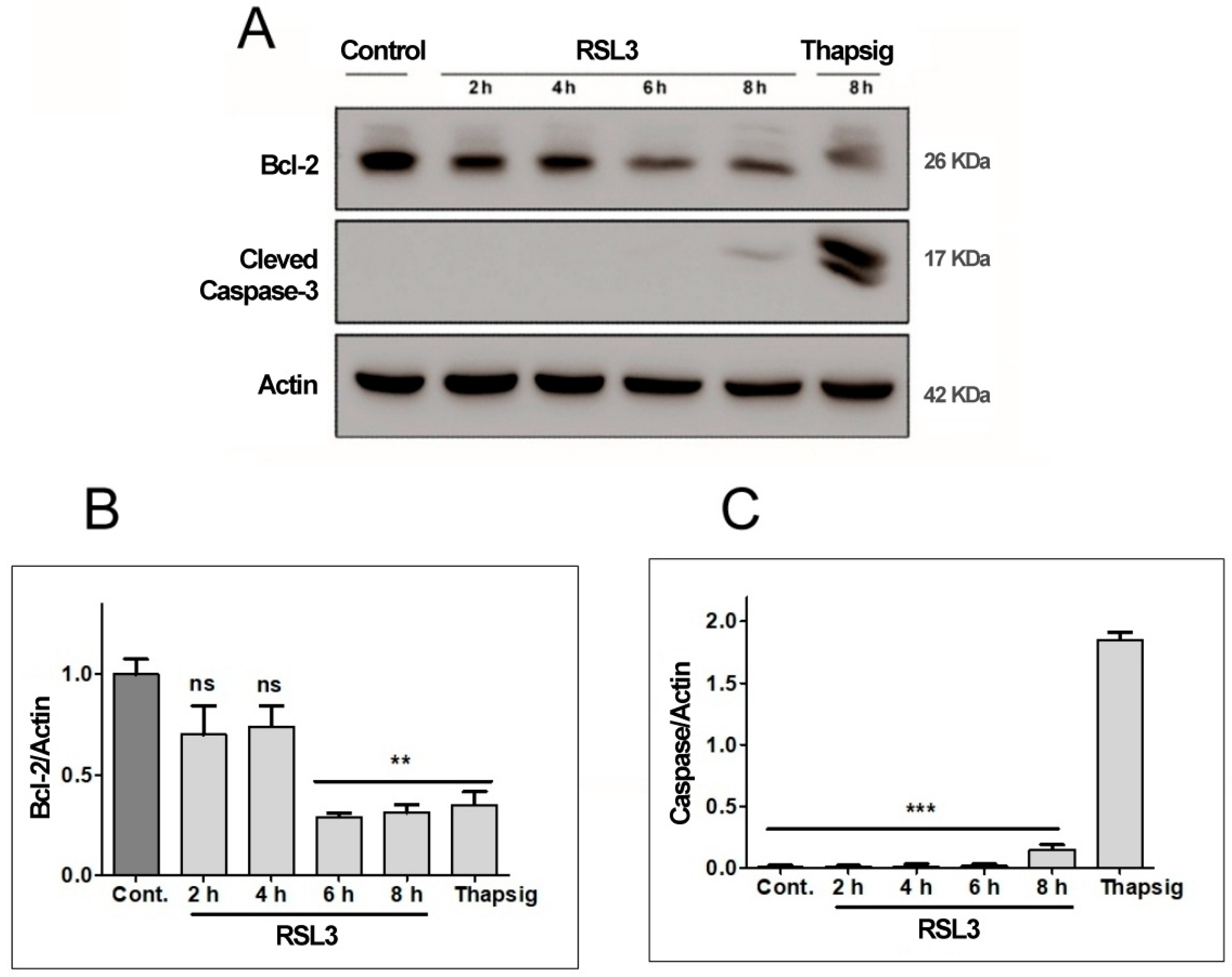

Since IP

3R is a highly regulated channel, its activation by RSL3 treatment could have several possible mediators. For example, the interaction between Bcl-2 and IP

3R is well documented, with the former acting as an inhibitor of the latter, through interaction via the BH-4 domain of Bcl-2 [

50]. We observed that RSL3 induced a decrease in Bcl-2, therefore, it is possible that a decreased inhibition of IP

3R by Bcl-2 may be one of the causes of the higher levels of cytoplasmic calcium. In addition, the increased ROS levels produced by RSL3 are likely to enhance IP

3R-mediated calcium release, since IP

3R channels increase their activity in response to oxidation [

23,

51].

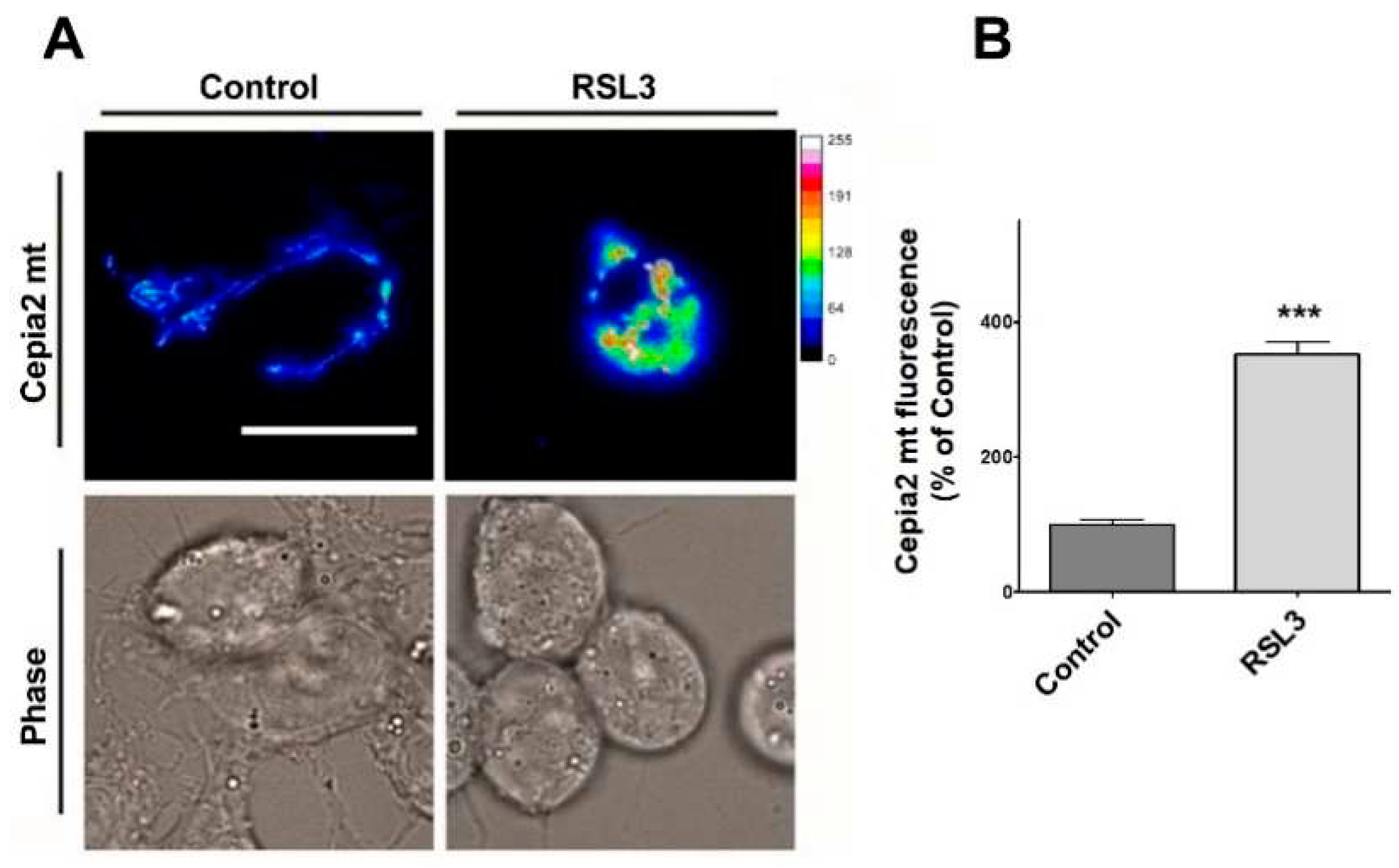

A crucial finding of this work was that RSL3 treatment induced calcium loading in mitochondria. This increase in mitochondrial calcium is a novel observation that is worthwhile to assess in other ferroptosis models. The elevation of mitochondrial calcium levels can stimulate the Krebs cycle and the electron transport chain, increasing the leakage of electrons and ROS generation [

52]. In fact, it was recently demonstrated that after exposure to erastin, hyperpolarization of the inner mitochondrial membrane and greater production of mitochondrial ROS occur, which further contribute to enhance lipid peroxidation [

53]. A putative counterpart is found in a recent report that showed that in a cold stress model of ferroptosis, activation of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter MCU by the mitochondrial calcium uptake regulator MICU1 is required for lipid peroxidation and subsequent ferroptosis [

54].

We observed that BAPTA-AM inhibited the lipid peroxidation induced by RSL3. Therefore, it is possible that calcium also participates in activating agents that contribute to the generation of lipid peroxides as, for example, the LOX enzymes, a group of enzymes widely linked to the initiation and development of ferroptotic death [

55,

56]. The membrane localization and catalytic activity of ALOX-5 and ALOX-15 are highly calcium dependent [

57,

58,

59]. Arguably, RSL3-induced calcium increases could stimulate lipid peroxidation through this mechanism. This proposal is in line with previous findings in NIH-3T3 cells which reported that increases in cytoplasmic calcium concentrations occurred prior to plasma membrane rupture [

60].

A notorious difference between oxytosis and ferroptosis is that in oxytosis, calcium enters the cytoplasm from the extracellular space, in a process known as store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) [

21,

61], whereas in the ferroptosis model described here and in a primary hippocampal cells model previously described by us [

27], calcium is released into the cytoplasm from an internal store, i.e., the ER.

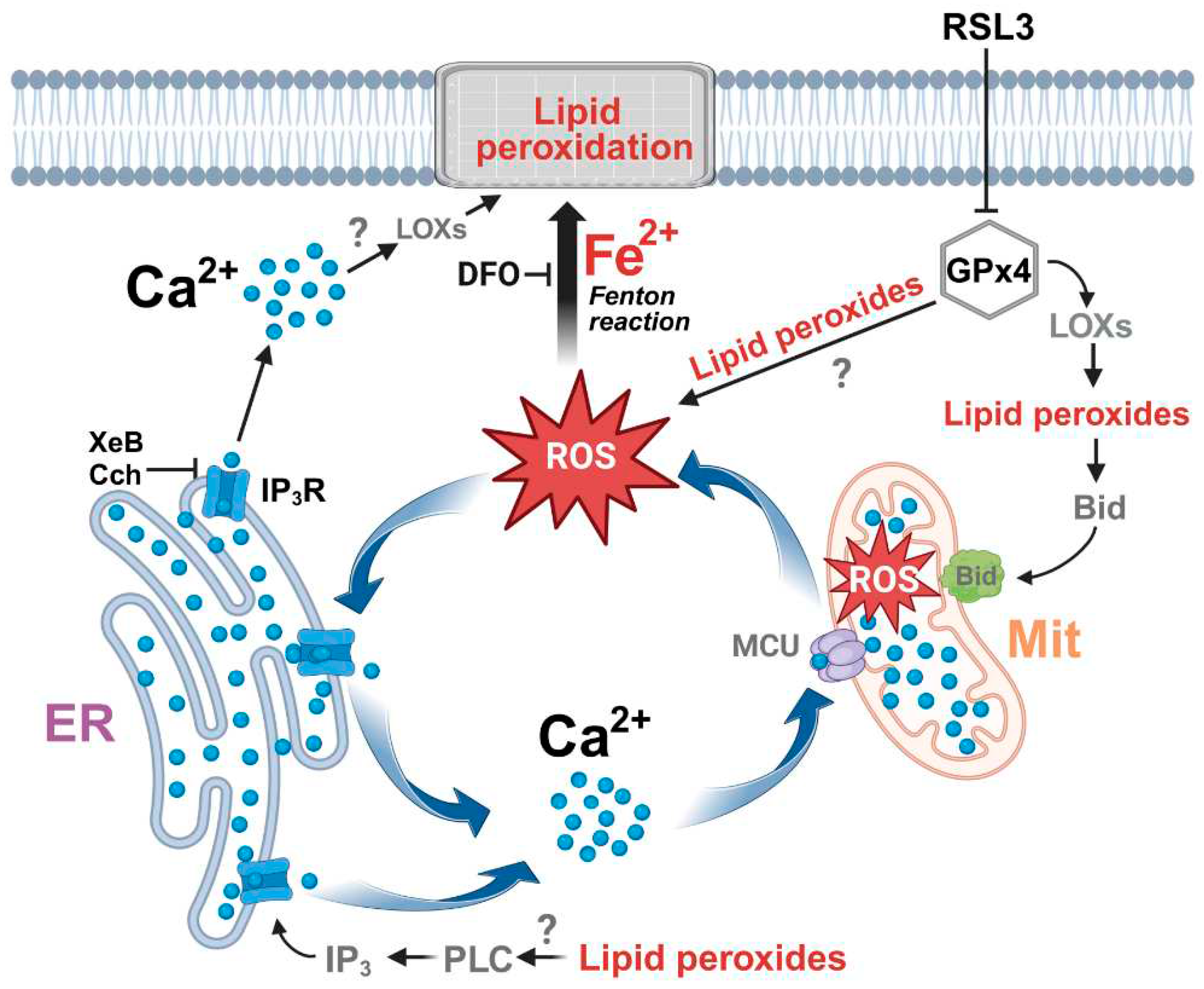

Overall, the data indicates that inhibition of GPx4 by RSL3 generates a vicious circle between calcium and ROS increase, as depicted in

Figure 11. An initial increase in ROS is generated either directly by the increase of lipid peroxides, through the axis LOX → lipid peroxide → Bid → mitochondrial dysfunction [

15], or through some other undefined mechanism. The increased oxidation tone activates the IP

3R with the ensuing increase in cytosolic calcium and increased mitochondrial calcium uptake by MCU, which in turn would intensify mitochondrial dysfunction by stimulating the production of ROS. Cell death occurs by the accumulation of lipid peroxidation damage and by the decreased synthesis of ATP, needed for repair processes. An alternative source of IP

3R stimulation, shown at the bottom of

Figure 11, is through the activation of phospholipase C by lipid peroxides [

62], with the subsequent activation of IP

3R by IP

3.

Figure 1.

RSL3 affects the viability of SH-SY5Y cells. A) Cells were treated with different concentrations of RSL3 for different times and viability was evaluated with the MTT assay. Viability at time= 0 was normalized to 100%. Values represent means of 5 replicates per experimental point of a representative experiment. N=3 independent experiments. B) Cells were treated for 3 h with 5 µM RSL3 or vehicle (DMSO, Control) and were stained with propidium iodine (PI) to evaluate dead cells in the population. Representative images are shown. Scale bar: 80 µm. C) Quantification of PI-positive cells. Values represent the mean ± SD from 200-250 cells per experimental condition; *** P <0.001.

Figure 1.

RSL3 affects the viability of SH-SY5Y cells. A) Cells were treated with different concentrations of RSL3 for different times and viability was evaluated with the MTT assay. Viability at time= 0 was normalized to 100%. Values represent means of 5 replicates per experimental point of a representative experiment. N=3 independent experiments. B) Cells were treated for 3 h with 5 µM RSL3 or vehicle (DMSO, Control) and were stained with propidium iodine (PI) to evaluate dead cells in the population. Representative images are shown. Scale bar: 80 µm. C) Quantification of PI-positive cells. Values represent the mean ± SD from 200-250 cells per experimental condition; *** P <0.001.

Figure 2.

Effects of RSL3 on cell morphology. Cells were treated for 3 h with 5 µM RSL3 or vehicle and then photographed using phase contrast. A) Representative images of Control and RSL3 treatment conditions. Scale bar 20 µm. B) Evaluation of area, perimeter, and roundness parameters. Values represent mean ± SEM. Between 62 and 123 cells were evaluated for each experimental condition; N=3 independent experiments; *** P <0.001.

Figure 2.

Effects of RSL3 on cell morphology. Cells were treated for 3 h with 5 µM RSL3 or vehicle and then photographed using phase contrast. A) Representative images of Control and RSL3 treatment conditions. Scale bar 20 µm. B) Evaluation of area, perimeter, and roundness parameters. Values represent mean ± SEM. Between 62 and 123 cells were evaluated for each experimental condition; N=3 independent experiments; *** P <0.001.

Figure 3.

RSL3 induces an increase in ROS production and lipid peroxidation. A) SH-SY5Y cells were loaded with H2DCFDA and were then treated at t = 0 with 10 µM or 20 µM RSL3 or 250 µM H2O2; DCF fluorescence intensity was recorded over time. Values represent means of 5 replicates per experimental condition. N=3 independent experiments. B) SH-SY5Y cells, treated for 3 h with 5 µM RSL3 or vehicle, were stained with BODIPY C11. Representative images of the overlapping values collected by the red (reduced, 590 nm emission) and green (oxidized, 510 nm emission) fluorescence channels for each condition are shown. Scale bar 20 µm. C) Quantification of the ratio of the green to red fluorescence intensity. Values represent mean ± SD of 150 cells; *** P<0.001. D) Cells were treated for 4 h without (control) or with 5 µM RSL3. Representative frames of HNE adducts immunofluorescence are shown. Scale bar 20 µm. The upper right corner shows a thermal fluorescence intensity scale. E) Quantification of HNE fluorescence intensity. Values represent mean ± SD for 100-120 cells per experimental condition, N=3 independent experiments, *** P <0.001.

Figure 3.

RSL3 induces an increase in ROS production and lipid peroxidation. A) SH-SY5Y cells were loaded with H2DCFDA and were then treated at t = 0 with 10 µM or 20 µM RSL3 or 250 µM H2O2; DCF fluorescence intensity was recorded over time. Values represent means of 5 replicates per experimental condition. N=3 independent experiments. B) SH-SY5Y cells, treated for 3 h with 5 µM RSL3 or vehicle, were stained with BODIPY C11. Representative images of the overlapping values collected by the red (reduced, 590 nm emission) and green (oxidized, 510 nm emission) fluorescence channels for each condition are shown. Scale bar 20 µm. C) Quantification of the ratio of the green to red fluorescence intensity. Values represent mean ± SD of 150 cells; *** P<0.001. D) Cells were treated for 4 h without (control) or with 5 µM RSL3. Representative frames of HNE adducts immunofluorescence are shown. Scale bar 20 µm. The upper right corner shows a thermal fluorescence intensity scale. E) Quantification of HNE fluorescence intensity. Values represent mean ± SD for 100-120 cells per experimental condition, N=3 independent experiments, *** P <0.001.

Figure 4.

RSL3 decreases Bcl-2 levels but does not induce Caspase-3 cleavage. Extracts of cells treated with 5 µM RSL3 for different times, or with 5 µM thapsigargin (Thapsig) for 8 h, were analyzed by western blot to evaluate Bcl-2 and cleaved Caspase-3 levels. Actin was used as a loading control. A) Image of a representative blot. B) Densitometric quantification of Bcl-2/Actin levels normalized to Control. C) Densitometric quantification of cleaved Caspase-3/Actin levels normalized to Control. after treatment with RSL3 for different times, or with 5 µM thapsigargin for 16 h. Mean ± SEM values are shown. N = 3 independent experiments; ns= not significant, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

Figure 4.

RSL3 decreases Bcl-2 levels but does not induce Caspase-3 cleavage. Extracts of cells treated with 5 µM RSL3 for different times, or with 5 µM thapsigargin (Thapsig) for 8 h, were analyzed by western blot to evaluate Bcl-2 and cleaved Caspase-3 levels. Actin was used as a loading control. A) Image of a representative blot. B) Densitometric quantification of Bcl-2/Actin levels normalized to Control. C) Densitometric quantification of cleaved Caspase-3/Actin levels normalized to Control. after treatment with RSL3 for different times, or with 5 µM thapsigargin for 16 h. Mean ± SEM values are shown. N = 3 independent experiments; ns= not significant, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

Figure 5.

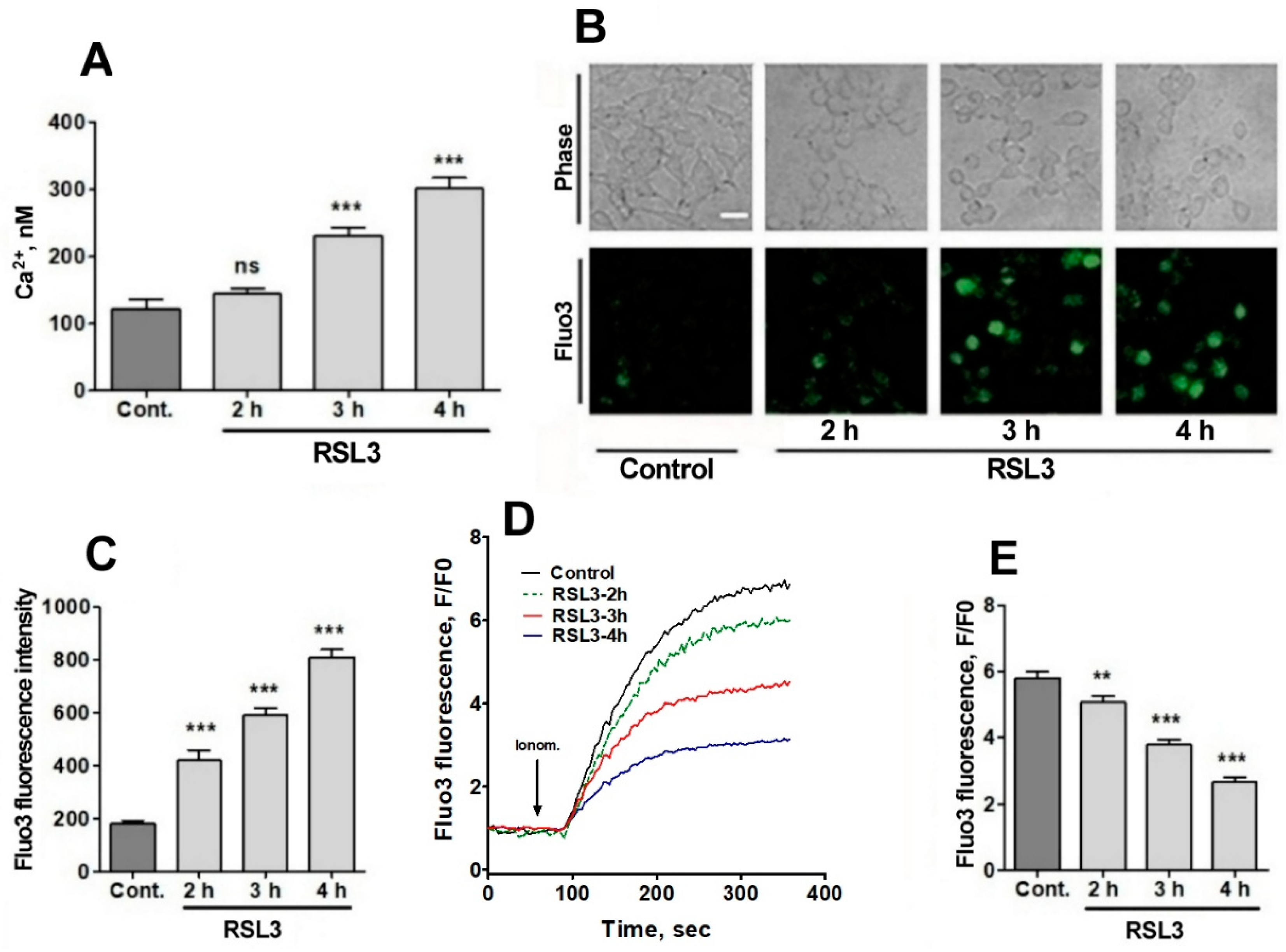

RSL3 alters calcium concentrations after a delay period. A) Cells pre-treated with 5 µM RSL3 for different times were loaded with fura-2 and fluorescence was recorded to subsequently determine cytoplasmic calcium concentrations. Values represent mean ± SEM of a representative experiment from 3 independent experiments with 3 replicates per experimental condition. Differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test. B) Cells pre-treated with 5 µM RSL3 or vehicle (DMSO, Control) were loaded with fluo-3 and fluorescence was recorded. Representative images of each treatment are shown. Scale bar 20 µm. C) Quantification of cell fluorescence after the different treatments. Values are given as mean ± SEM; 40 cells per condition. D) Plots of the ratio of fluorescence intensity over initial fluorescence (F/F0) as a function of time, before and after the addition of ionomycin (arrow). E) Maximum F/F0 ratio reached after the addition of ionomycin for each condition. Mean ± SEM of the last three points for each experimental condition with points in triplicate. ns = not significant; **P<0.01; ***P< 0.001.

Figure 5.

RSL3 alters calcium concentrations after a delay period. A) Cells pre-treated with 5 µM RSL3 for different times were loaded with fura-2 and fluorescence was recorded to subsequently determine cytoplasmic calcium concentrations. Values represent mean ± SEM of a representative experiment from 3 independent experiments with 3 replicates per experimental condition. Differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test. B) Cells pre-treated with 5 µM RSL3 or vehicle (DMSO, Control) were loaded with fluo-3 and fluorescence was recorded. Representative images of each treatment are shown. Scale bar 20 µm. C) Quantification of cell fluorescence after the different treatments. Values are given as mean ± SEM; 40 cells per condition. D) Plots of the ratio of fluorescence intensity over initial fluorescence (F/F0) as a function of time, before and after the addition of ionomycin (arrow). E) Maximum F/F0 ratio reached after the addition of ionomycin for each condition. Mean ± SEM of the last three points for each experimental condition with points in triplicate. ns = not significant; **P<0.01; ***P< 0.001.

Figure 6.

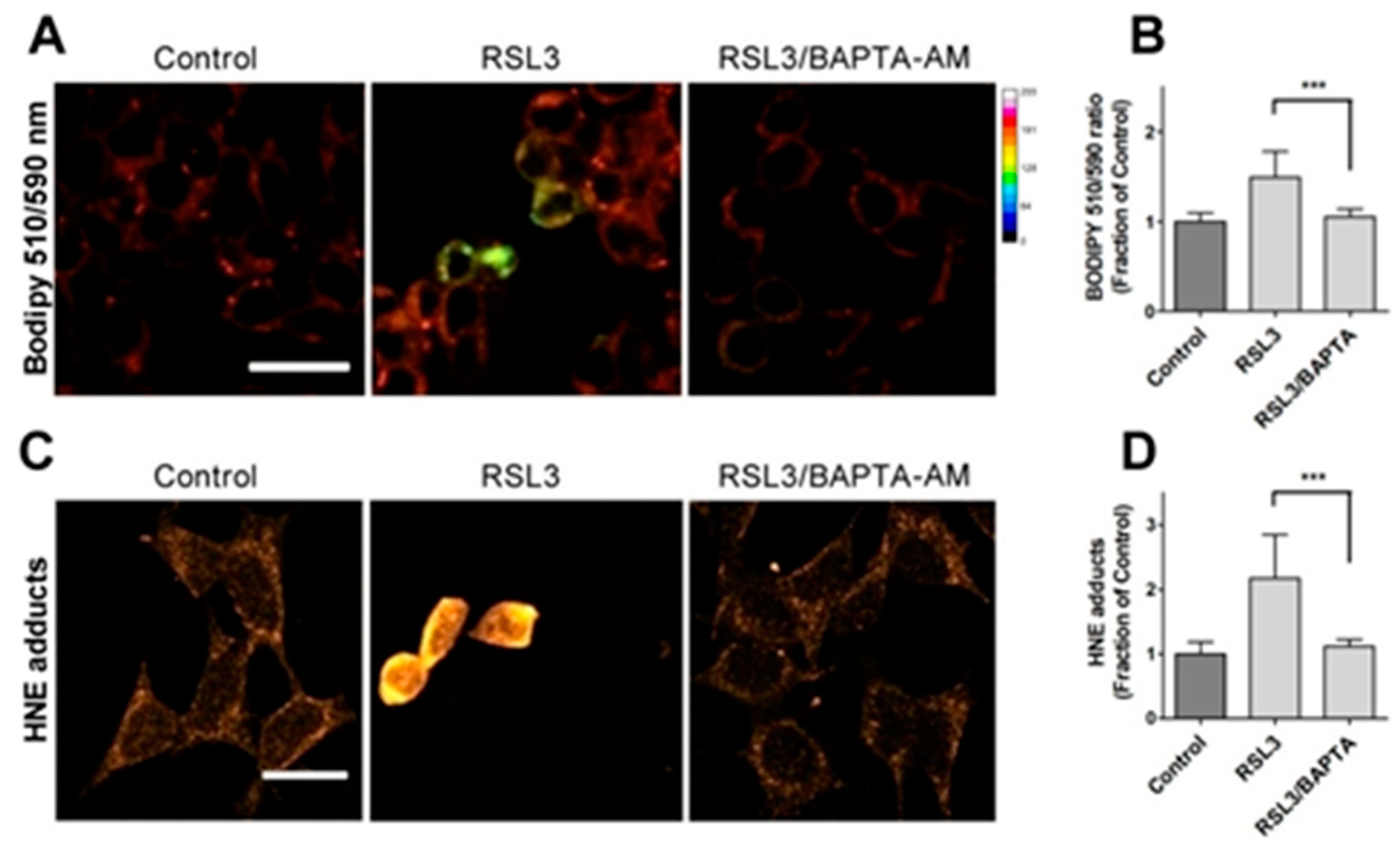

Calcium chelation protects cells against RSL3-induced lipid peroxidation. Cells were pre-incubated for 1 h with 5 µM BAPTA-AM followed by co-incubation for 3 h with 5 µM RSL3 and analysis of lipid peroxidation with either BODIPY C11 or anti-HNE immunofluorescence as described in Methods. A) Representative images of BODIPY fluorescence upon treatment with RSL3, without (Control) or after pre-treatment with BAPTA-AM. Scale bar 20 µm. B) Quantification of the ratio of fluorescence intensity of the oxidized (green) channel to that of the reduced (red) channel. At least 80 cells per condition were quantified from N=3 independent experiments. Mean ± SD values are shown. C) Representative images of immunodetection against 4-HNE adducts. Scale bar 15 µm. D) Quantification of fluorescence intensity. Values represent mean ± SD from 75-90 cells quantified for each experimental condition from N=3 independent experiments. Both in B and C differences were evaluated by one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett´s post hoc test. ***P<0.001.

Figure 6.

Calcium chelation protects cells against RSL3-induced lipid peroxidation. Cells were pre-incubated for 1 h with 5 µM BAPTA-AM followed by co-incubation for 3 h with 5 µM RSL3 and analysis of lipid peroxidation with either BODIPY C11 or anti-HNE immunofluorescence as described in Methods. A) Representative images of BODIPY fluorescence upon treatment with RSL3, without (Control) or after pre-treatment with BAPTA-AM. Scale bar 20 µm. B) Quantification of the ratio of fluorescence intensity of the oxidized (green) channel to that of the reduced (red) channel. At least 80 cells per condition were quantified from N=3 independent experiments. Mean ± SD values are shown. C) Representative images of immunodetection against 4-HNE adducts. Scale bar 15 µm. D) Quantification of fluorescence intensity. Values represent mean ± SD from 75-90 cells quantified for each experimental condition from N=3 independent experiments. Both in B and C differences were evaluated by one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett´s post hoc test. ***P<0.001.

Figure 7.

Both BAPTA and DFO protect against RSL3-induced decrease in cell viability. Cells were incubated for 90 min with 300 µM Verapamil (Verap), 5 µM Nifedipine (Nifed) or 100 µM CoCl2 (A) or with 25 µM DFO, 2.5 mM EGTA or 2.5 µM BAPTA-AM (B), followed by incubation for 4 h with 5 µM RSL3. After that, cell viability was estimated by the MTT assay. Values represent mean ± SEM. N=3 independent experiments with determinations done in sextuplicate. Differences were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. *** P< 0.001 compared to RSL3 alone treatment; ns= not significant.

Figure 7.

Both BAPTA and DFO protect against RSL3-induced decrease in cell viability. Cells were incubated for 90 min with 300 µM Verapamil (Verap), 5 µM Nifedipine (Nifed) or 100 µM CoCl2 (A) or with 25 µM DFO, 2.5 mM EGTA or 2.5 µM BAPTA-AM (B), followed by incubation for 4 h with 5 µM RSL3. After that, cell viability was estimated by the MTT assay. Values represent mean ± SEM. N=3 independent experiments with determinations done in sextuplicate. Differences were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. *** P< 0.001 compared to RSL3 alone treatment; ns= not significant.

Figure 8.

The role of IP3R channels in RSL3-induced ferroptosis. A) SH-SY5Y cells were pre-incubated for 1 h with 100 µM Ryanodine, 10 µM XeB or 1 mM Cch and were then incubated for 4 h with RSL3. Viability was determined by the MTT assay; ***P< 0.001. B) Representative Western blots against IP3R1 after Cch treatments for 0, 1, 4 or 6 h. C) Quantification of relative protein levels of IP3R1 after Cch treatment. Values represent the mean ± SD from N=3 independent experiments; ***P<0.001 compared to Control.

Figure 8.

The role of IP3R channels in RSL3-induced ferroptosis. A) SH-SY5Y cells were pre-incubated for 1 h with 100 µM Ryanodine, 10 µM XeB or 1 mM Cch and were then incubated for 4 h with RSL3. Viability was determined by the MTT assay; ***P< 0.001. B) Representative Western blots against IP3R1 after Cch treatments for 0, 1, 4 or 6 h. C) Quantification of relative protein levels of IP3R1 after Cch treatment. Values represent the mean ± SD from N=3 independent experiments; ***P<0.001 compared to Control.

Figure 9.

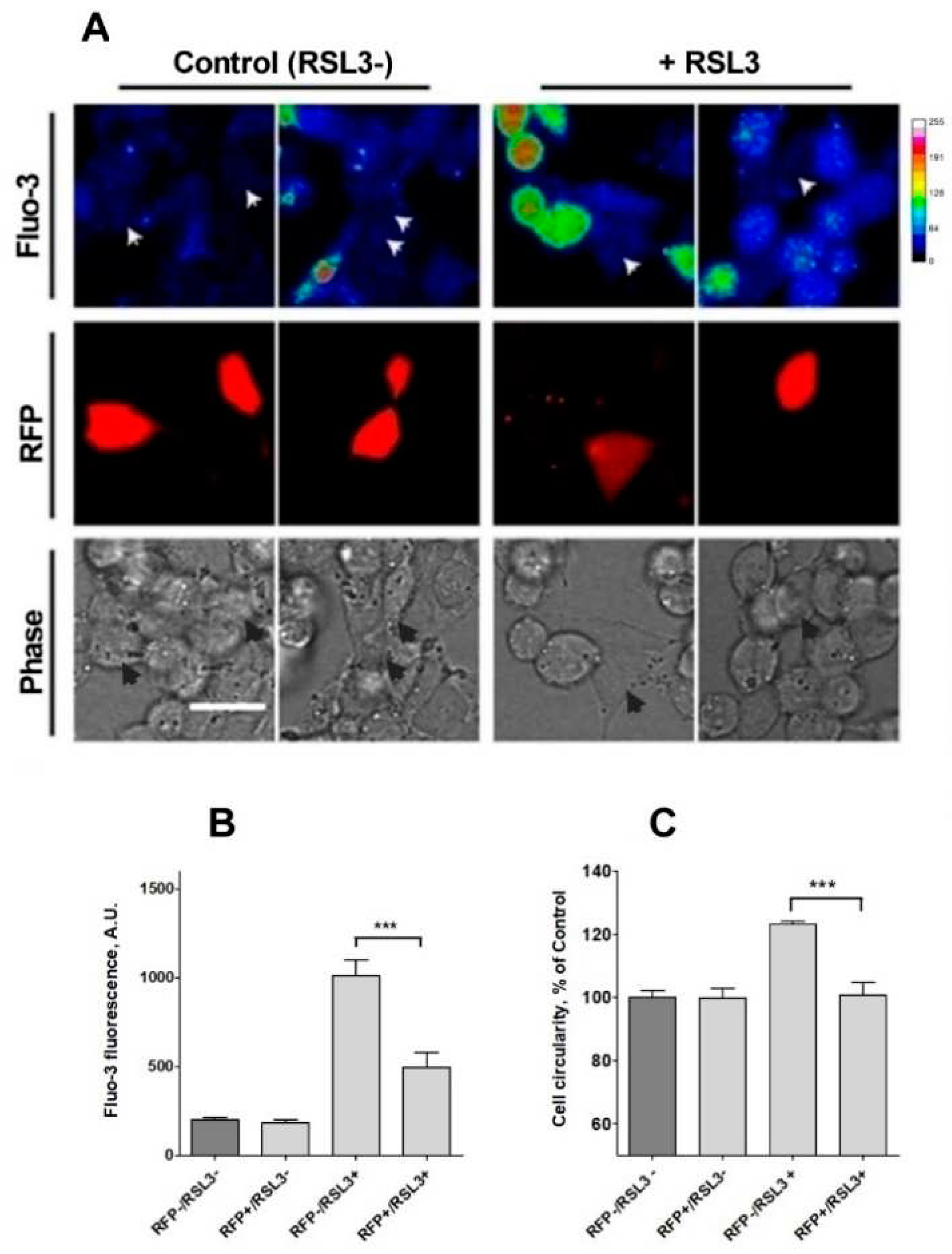

Knockdown of IP3R1 reduces the increase in intracellular calcium concentration induced by RSL3. Cells previously transfected with a shRNA construct against IP3R1 with a red fluorescence protein tag (RFP+) were treated for 4 h with 5 µM RSL3 or vehicle, then loaded with fluo-3 and frames were obtained with red and green fluorescence filters. A) Representative images in thermal scale of non-treated cells (columns 1 and 2) and RSL3-treated cells (columns 3 and 4). Scale bar 20 µm. B) Quantification of fluo-3 fluorescence in RFP+ cells, which corresponds to IP3R1 shRNA transfected cells, and RFP- cells, which do not express the IP3R1 construct, without (RSL3-) or with (RSL3+) RSL3 treatment. C) Estimation of roundness in RFP+ and RFP- cells treated or not with RSL3. Values represent mean ± SEM. Between 32 and 115 cells were evaluated per experimental condition from 2 independent experiments. ***P= 0.001 comparing the RFP-/RSL3+ and the RFP-/RSL3+ conditions. No significant changes were detected between the RFP-/RSL3-, RFP+/RSL3- and RFP+/RSL3+ conditions.

Figure 9.

Knockdown of IP3R1 reduces the increase in intracellular calcium concentration induced by RSL3. Cells previously transfected with a shRNA construct against IP3R1 with a red fluorescence protein tag (RFP+) were treated for 4 h with 5 µM RSL3 or vehicle, then loaded with fluo-3 and frames were obtained with red and green fluorescence filters. A) Representative images in thermal scale of non-treated cells (columns 1 and 2) and RSL3-treated cells (columns 3 and 4). Scale bar 20 µm. B) Quantification of fluo-3 fluorescence in RFP+ cells, which corresponds to IP3R1 shRNA transfected cells, and RFP- cells, which do not express the IP3R1 construct, without (RSL3-) or with (RSL3+) RSL3 treatment. C) Estimation of roundness in RFP+ and RFP- cells treated or not with RSL3. Values represent mean ± SEM. Between 32 and 115 cells were evaluated per experimental condition from 2 independent experiments. ***P= 0.001 comparing the RFP-/RSL3+ and the RFP-/RSL3+ conditions. No significant changes were detected between the RFP-/RSL3-, RFP+/RSL3- and RFP+/RSL3+ conditions.

Figure 10.

RSL3 induces an increase in mitochondrial calcium levels. Cells transfected with the mitochondrial calcium sensor CEPIA2mt were treated with 5 µM RSL3 for 4 h or with control solution, and the fluorescence intensity was recorded. A) Representative images of both conditions shown in thermal scale (right-hand bar). Size bar 30 µm. B) Quantification of fluorescence intensity. Values represent Mean ± SEM from 58-62 cells quantified for each experimental condition. Difference between mean values was determined by unpaired two-tail t-test. N=2 independent experiments. ***P< 0.0001.

Figure 10.

RSL3 induces an increase in mitochondrial calcium levels. Cells transfected with the mitochondrial calcium sensor CEPIA2mt were treated with 5 µM RSL3 for 4 h or with control solution, and the fluorescence intensity was recorded. A) Representative images of both conditions shown in thermal scale (right-hand bar). Size bar 30 µm. B) Quantification of fluorescence intensity. Values represent Mean ± SEM from 58-62 cells quantified for each experimental condition. Difference between mean values was determined by unpaired two-tail t-test. N=2 independent experiments. ***P< 0.0001.

Figure 11.

The effect of RSL3-induced ferroptosis on intracellular calcium dynamics in SH-SY5Y cells. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Mit, mitochondria; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DFO, iron chelator desferoxamine; MCU, mitochondrial calcium uniporter; LOXs, lipoxygenases; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; IP3R, IP3 receptor; PLC, Phospholipase C; XeB, xestospongin B; Cch, carbachol. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Figure 11.

The effect of RSL3-induced ferroptosis on intracellular calcium dynamics in SH-SY5Y cells. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Mit, mitochondria; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DFO, iron chelator desferoxamine; MCU, mitochondrial calcium uniporter; LOXs, lipoxygenases; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; IP3R, IP3 receptor; PLC, Phospholipase C; XeB, xestospongin B; Cch, carbachol. Figure created with BioRender.com.