Submitted:

24 January 2024

Posted:

25 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the experiment site

2.2. Experimental materials

2.4. Sample collection and determination

2.4.1. Harvesting of rapeseed seedlings:

2.4.2. Collection of rapeseed rhizosphere soil

2.4.3. Determination of plant growth indicators

2.4.4. Rhizosphere microorganism determination

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of different fertilization patterns and water treatments on the growth of rapeseed during the seedling stage

| Treatment cord | Fertilization mode | Water treatment | Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| CZ-7 | Conventional fertilization | waterlogging stress | Flooded for 7 days |

| YZ-7 | Supplement organic fertilizer | waterlogging stress | Flooded for 7 days |

| WZ-7 | Supplement microbial fertilizer | waterlogging stress | Flooded for 7 days |

| CW-7 | Conventional fertilization | Normal water supply | Control |

| YW-7 | Supplement organic fertilizer | Normal water supply | Control |

| WW-7 | Supplement microbial fertilizer | Normal water supply | Control |

| CZ-14 | Conventional fertilization | waterlogging stress | End flooding and restore 14 days |

| YZ-14 | Supplement organic fertilizer | waterlogging stress | End flooding and restore 14 days |

| WZ-14 | Supplement microbial fertilizer | waterlogging stress | End flooding and restore 14 days |

| CW-14 | Conventional fertilization | Normal water supply | Control |

| YW-14 | Supplement organic fertilizer | Normal water supply | Control |

| WW-14 | Supplement microbial fertilizer | Normal water supply | Control |

| Treatment | Plant height | Stem diameter | Aboveground part/g | Root/g | Total weight /g | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (cm) | (cm) | Fresh weight | Dry weight | Fresh weight | Dry weight | Total fresh weight | Total dry weight | ||

| YZ-7 | 39.03 g | 0.94 f | 77.89 h | 7.72 h | 7.55 g | 1.61 f | 85.44 h | 9.33 h | |

| CZ-7 | 37.90 g | 0.80 e | 67.08 i | 6.34 i | 5.99 h | 1.22 f | 73.07 i | 7.57 i | |

| WZ-7 | 40.43 fg | 1.09 d | 75.98 h | 7.76 h | 7.59 g | 1.49 f | 83.57 h | 9.25 h | |

| YW-7 | 45.00 de | 1.24 c | 94.80 f | 11.55 g | 10.99 e | 2.30 de | 105.79 f | 13.85 g | |

| CW-7 | 43.33 ef | 1.09 d | 86.37 g | 11.06 g | 9.51 f | 2.09 e | 95.88 g | 13.15 g | |

| WW-7 | 46.50 cde | 1.22 cd | 89.65 fg | 11.12 g | 11.42 e | 2.35 de | 101.07 fg | 13.46 g | |

| YZ-14 | 47.67cd | 1.47 b | 152.40 d | 19.08 d | 14.97 c | 3.33 c | 167.37 d | 22.41 d | |

| CZ-14 | 45.03de | 1.26 c | 137.47 e | 15.13 f | 12.85 d | 2.71 d | 150.32 e | 17.84 f | |

| WZ-14 | 45.77de | 1.40 b | 147.10 d | 17.02 e | 14.98 c | 3.26 c | 162.08 d | 20.27 e | |

| YW-14 | 56.13a | 1.92 a | 196.66 a | 28.37 a | 20.27 a | 4.67 a | 216.93 a | 33.04 a | |

| CW-14 | 50.20bc | 1.85 a | 175.22 c | 25.59 c | 18.08 b | 4.13 b | 193.30 c | 29.72 c | |

| WW-14 | 51.90b | 1.92 a | 188.89 b | 27.09 b | 20.54 a | 4.68 a | 209.43 b | 31.77 b | |

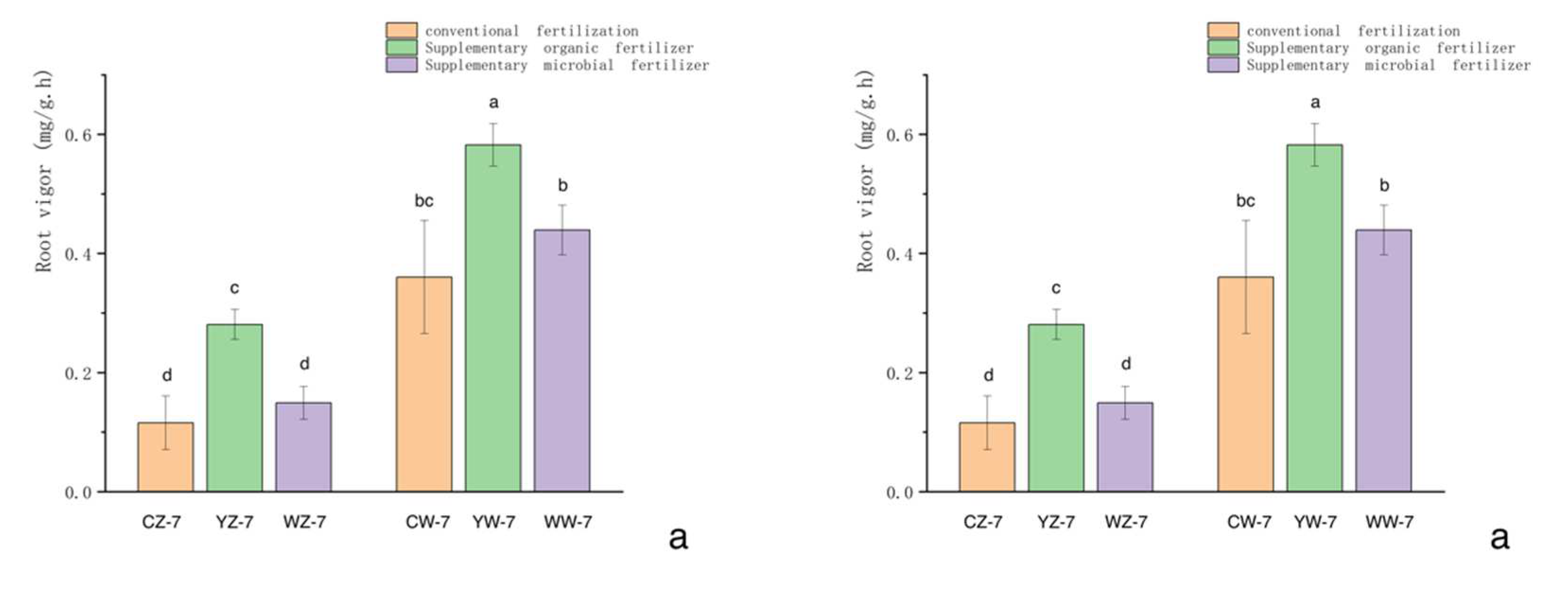

3.2. Effect of different fertilization patterns and water treatments on root vigor of rapeseed during seedling stage

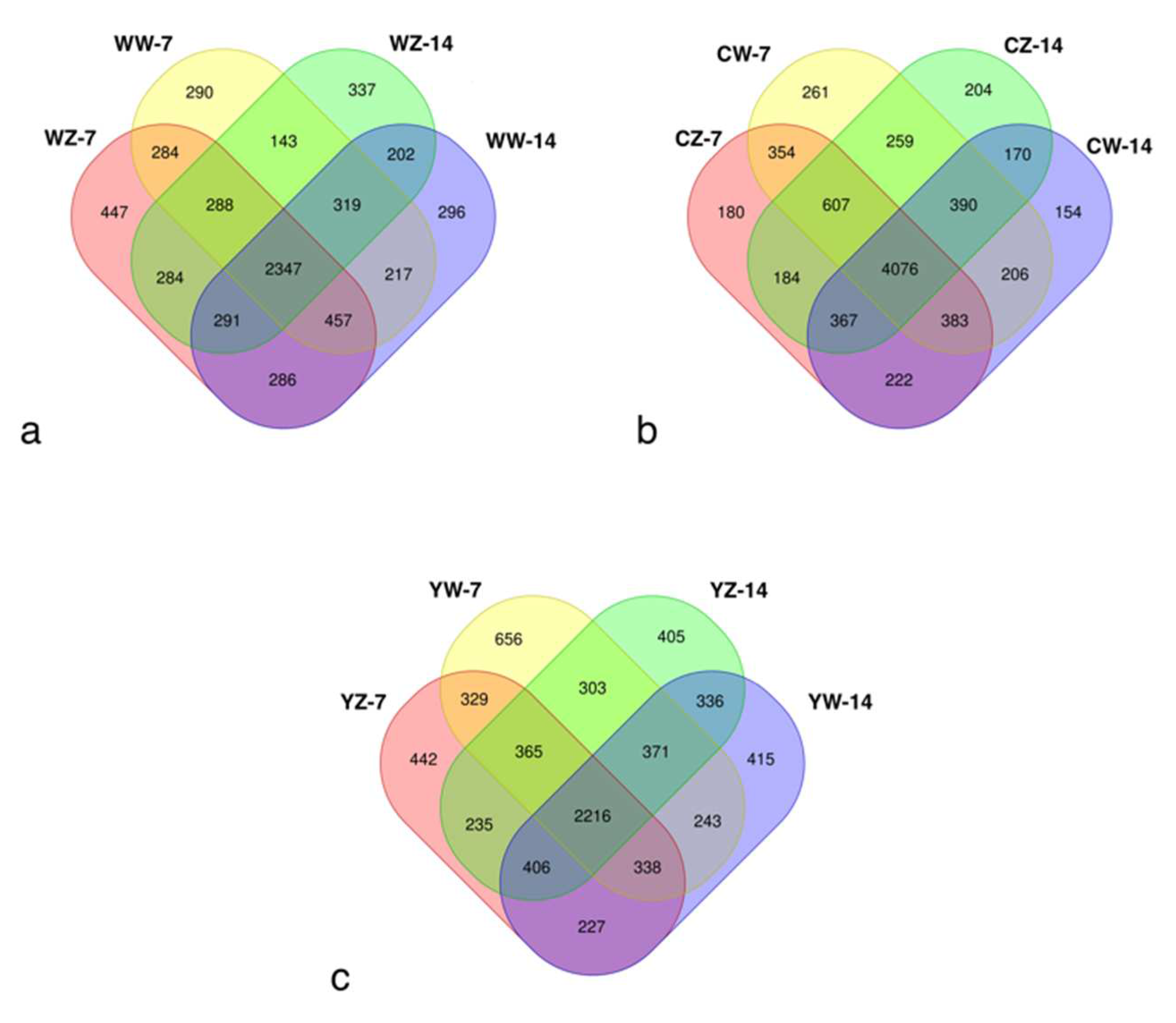

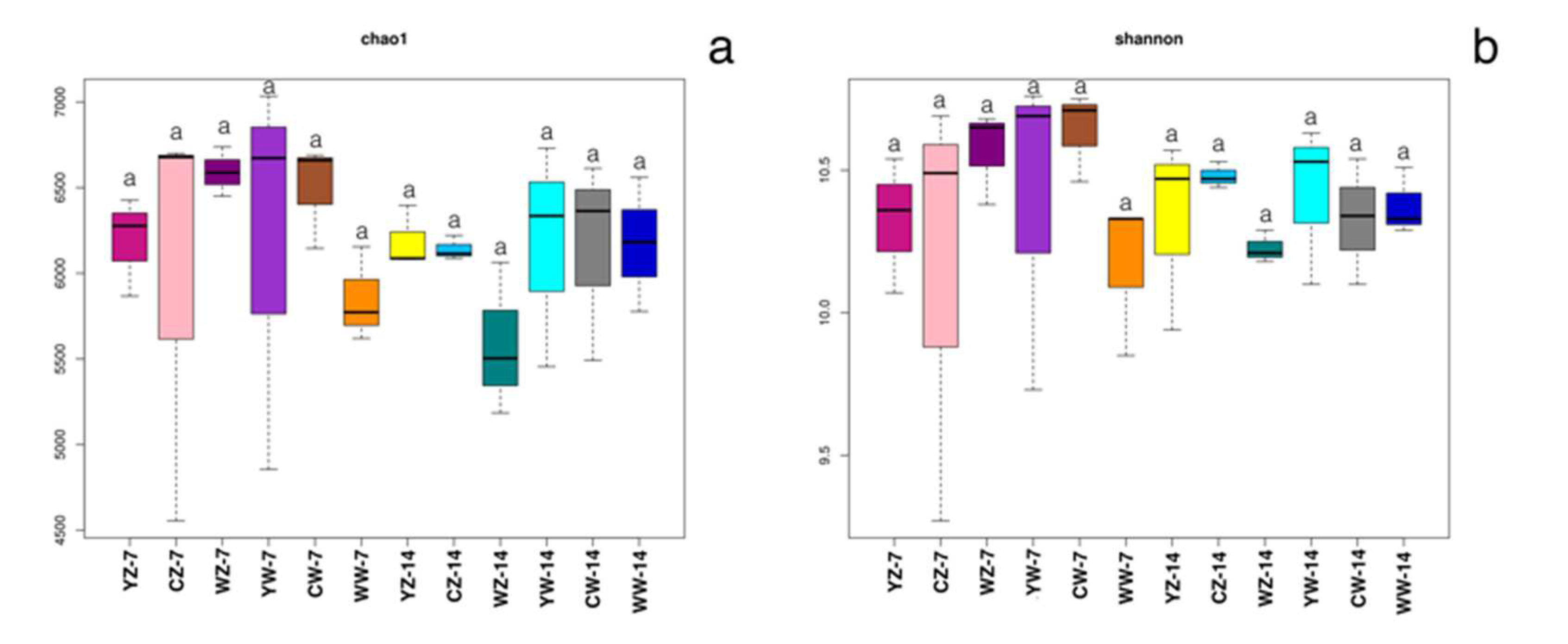

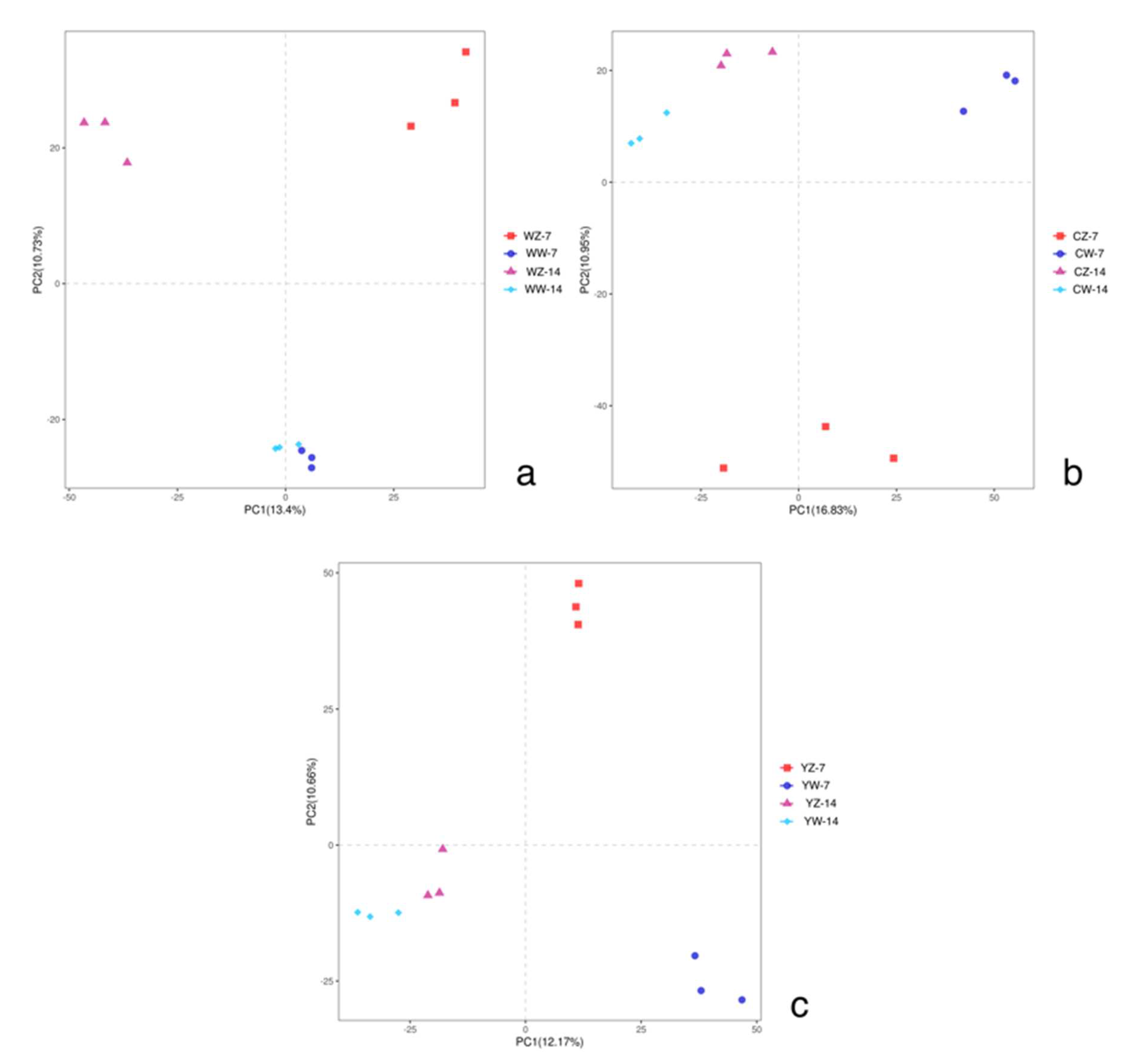

3.3. Analysis of high-throughput sequencing results and relative abundance and diversity of rhizosphere bacteria

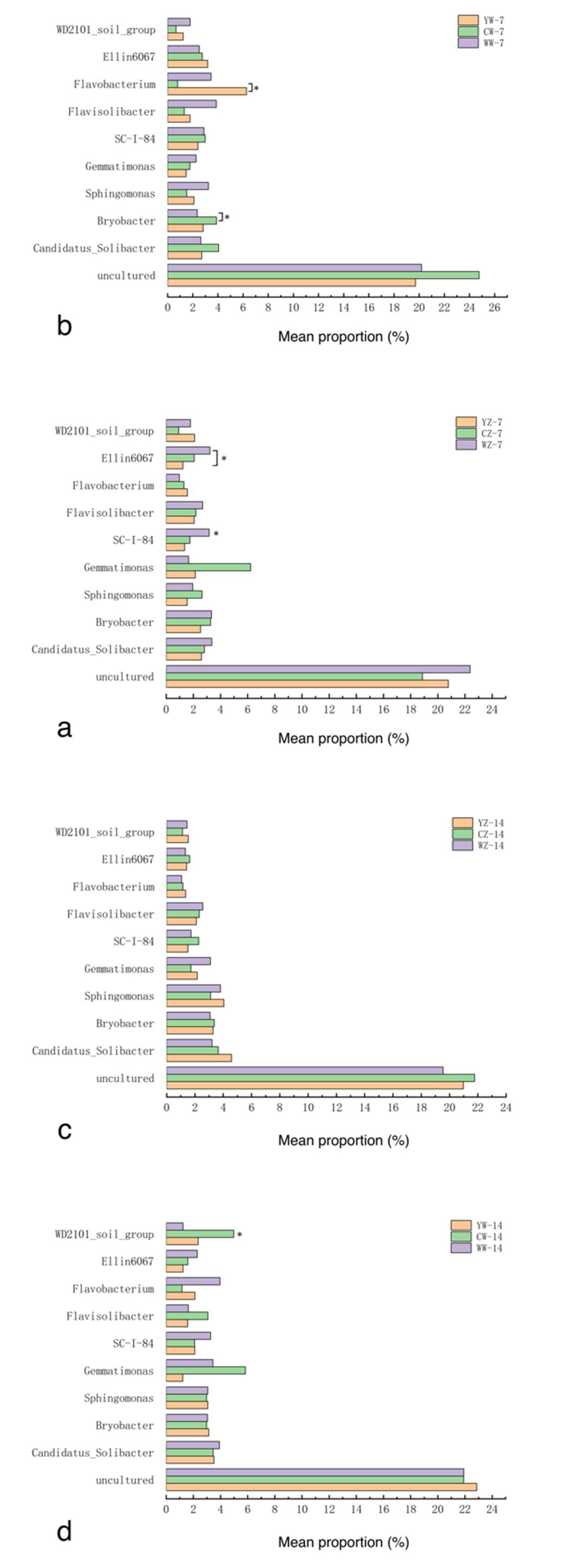

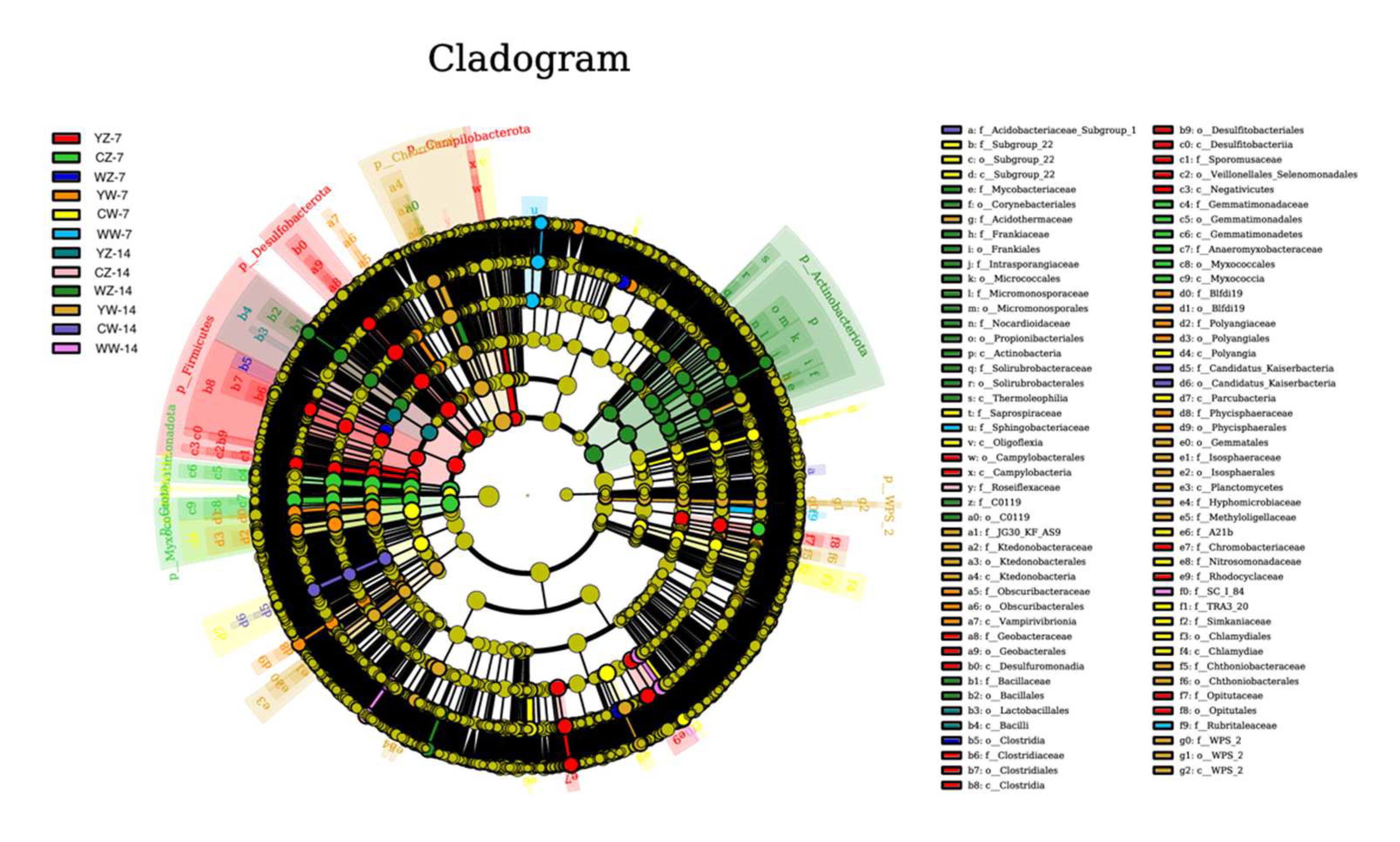

3.4. Analysis of rhizosphere bacteria Bate in rapeseed seedling stage under different fertilization modes and water treatments

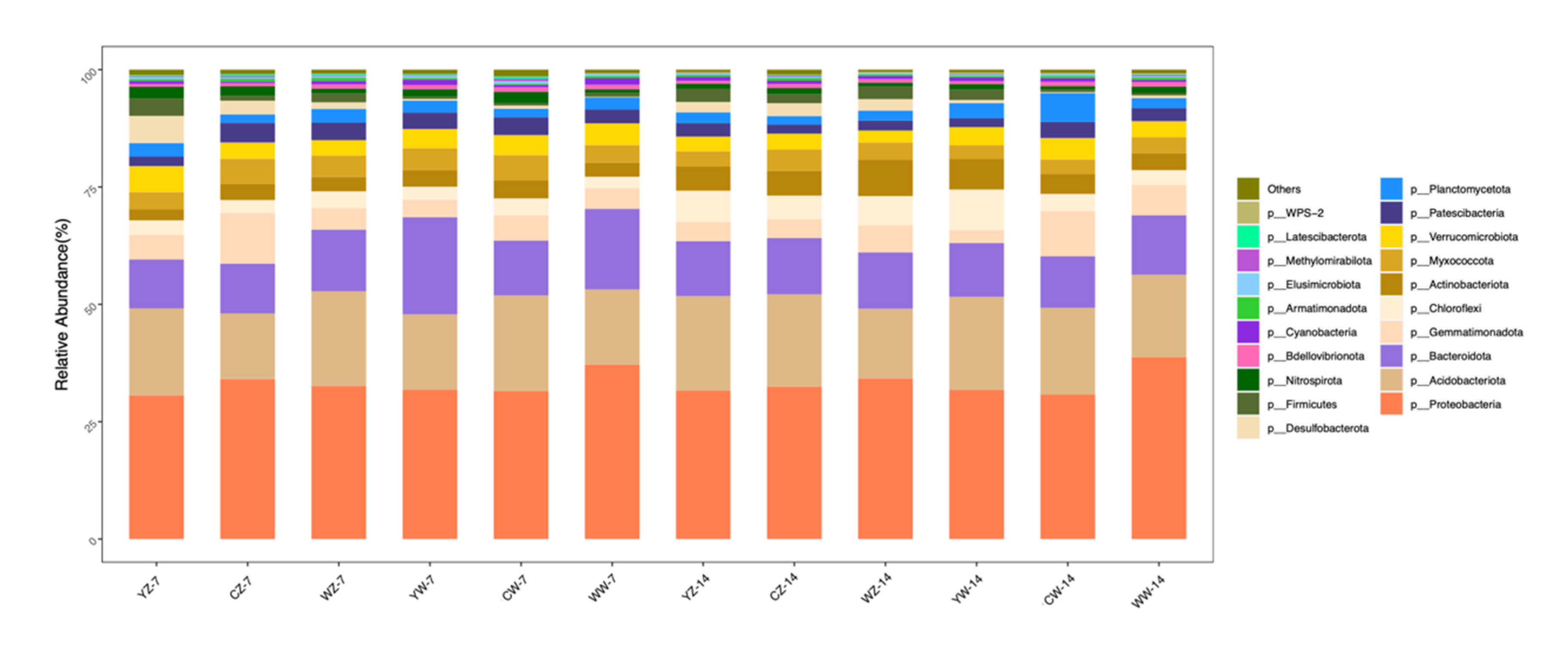

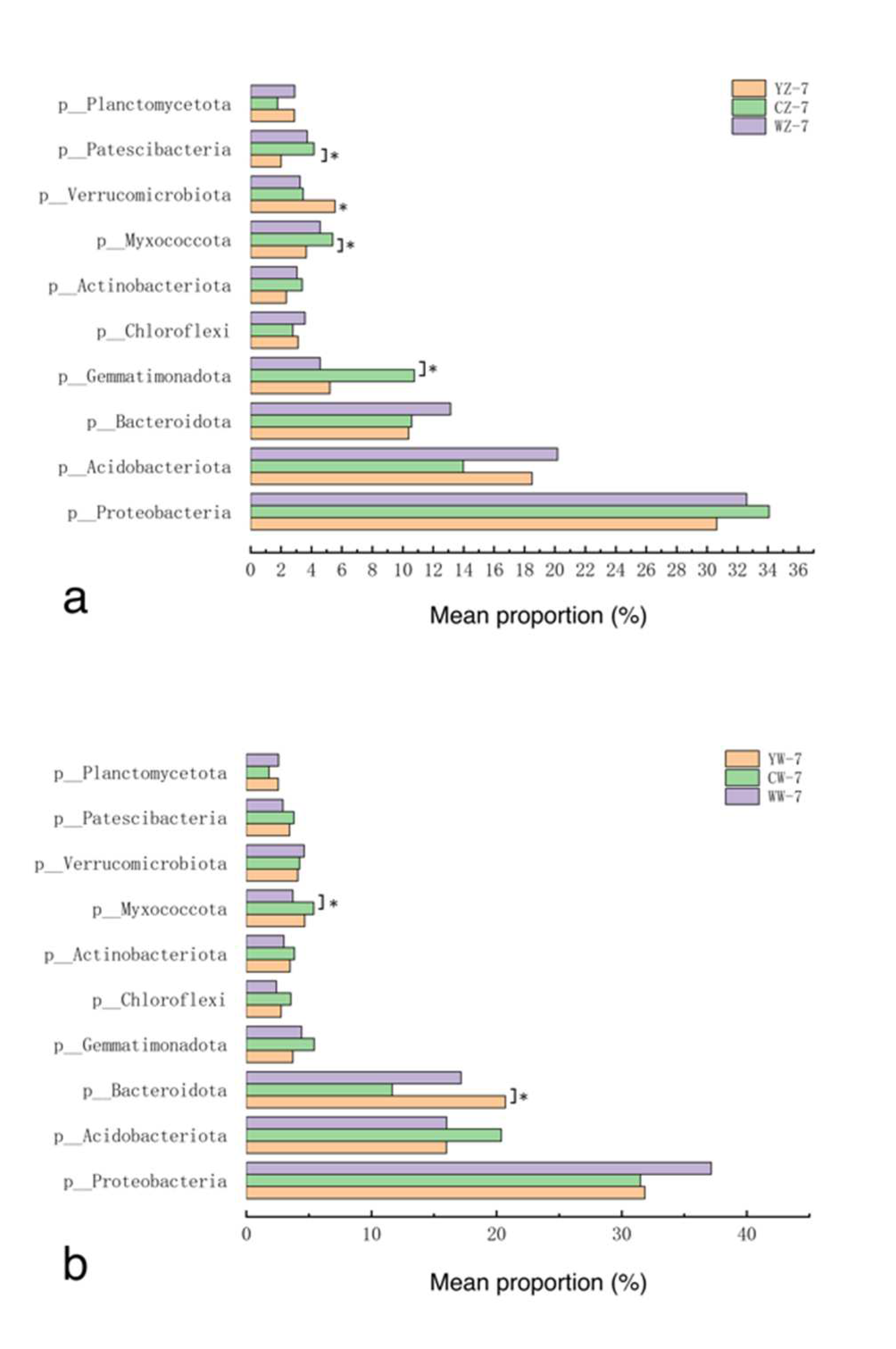

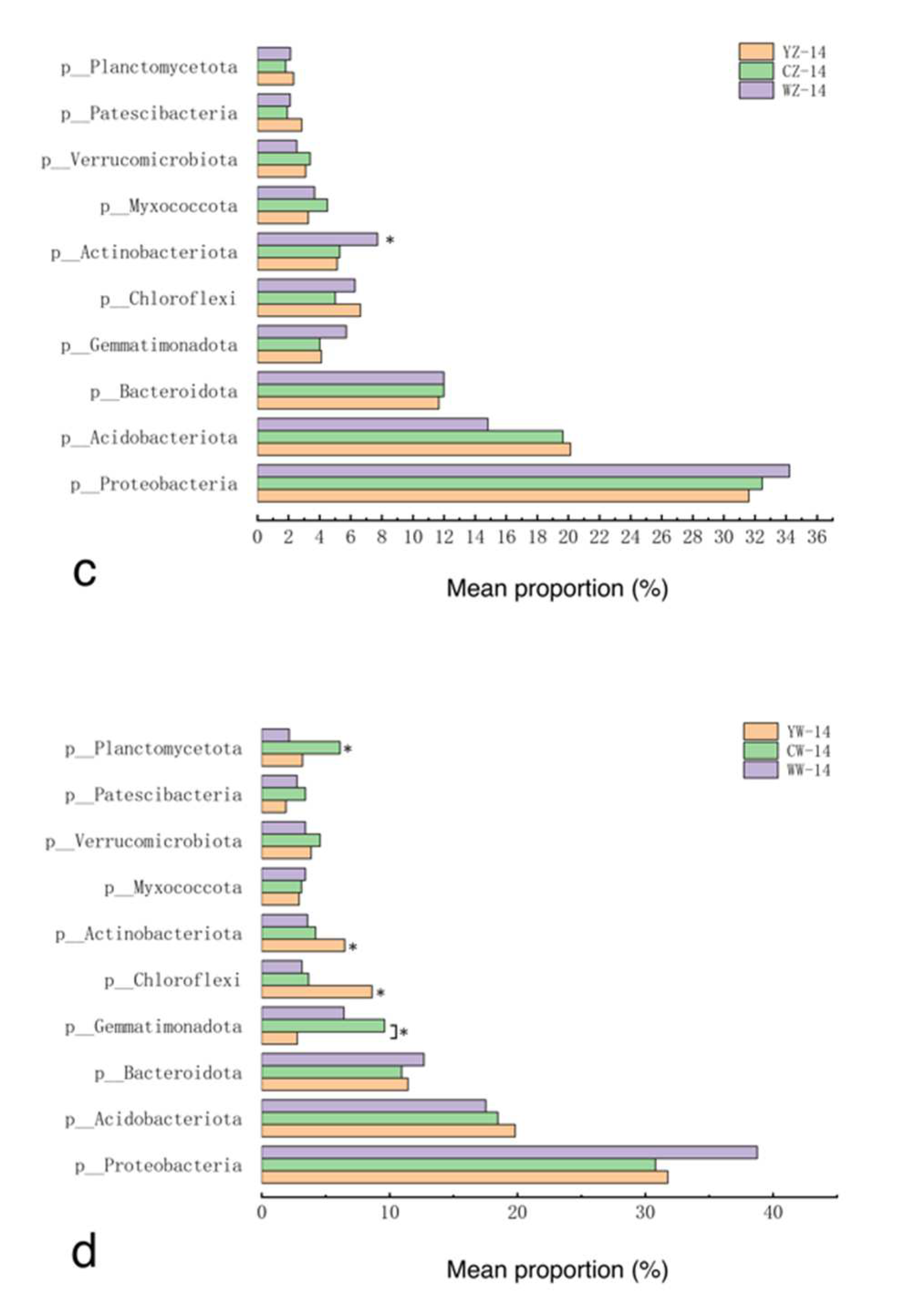

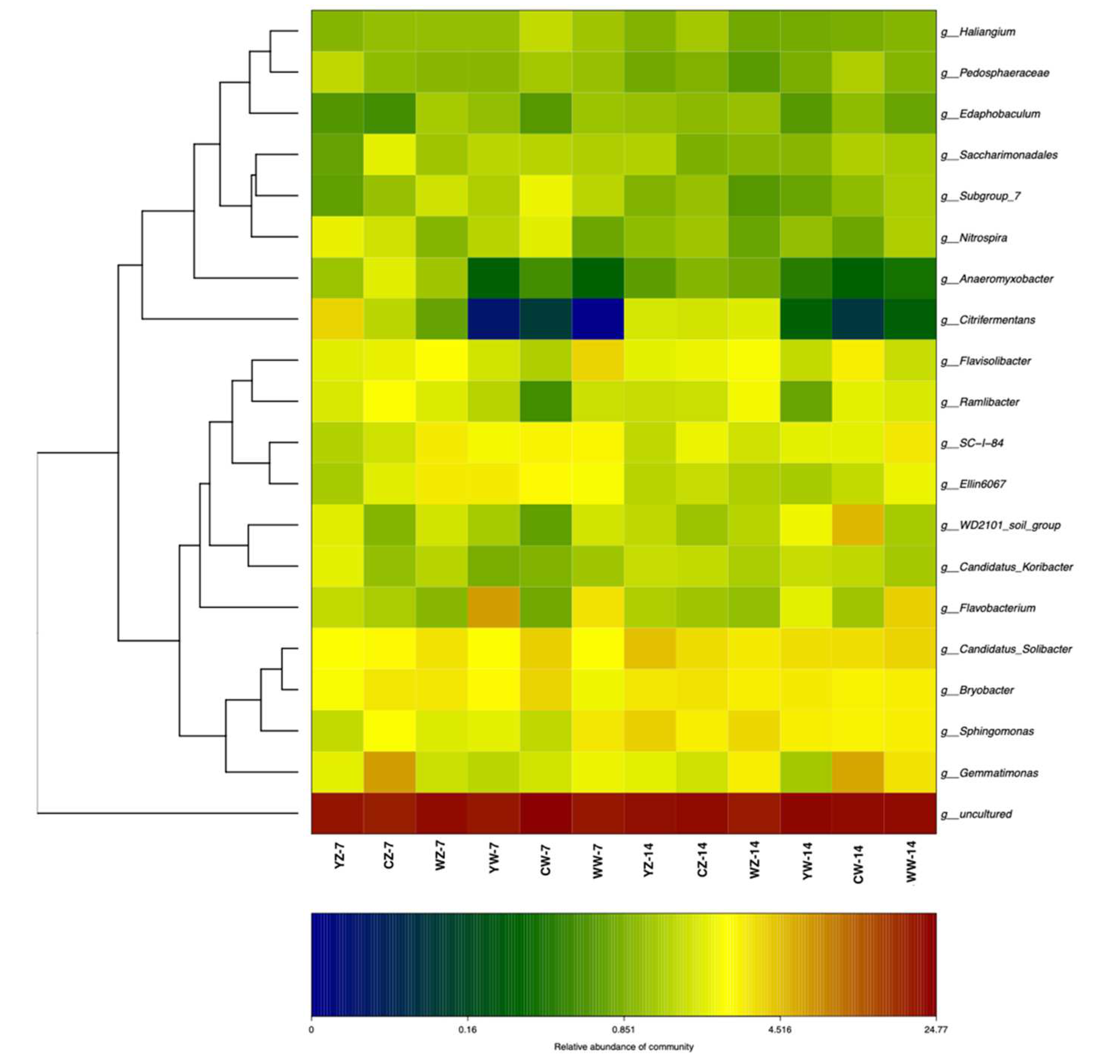

3.5. Analysis of rhizosphere soil community composition of rapeseed seedlings under different fertilization patterns and water treatments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Author Contributions: Conceptualization, C.G. and M.G.; methodology, X.W. and B.H.; software, J.W. and D.Z. and B.Z.; investigation, X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W. ; writing—review and editing, M.G.; visualization, X.W.; supervision, C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

- Funding: This research was funded by the National Rapeseed Industrial Technology System (CARS- 12) and the Hunan Agriculture Research System of DARA (Xiangnongfa (2022)).

- Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

- Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, C-J. A statistical analysis of the storm flood disasters in China. J Catastrophol, (in Chinese with English abstract). 1996, 11, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H-L. Practical Cultivation of Rapeseed. S: Shanghai, 1987.

- 3. Oil Crops Research Institute Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Rapeseed Cultivation in China. Beijing: Agriculture Press, 1990. (in Chinese)

- Hu Q, Hua W, Yin Y; et al. Rapeseed research and production in China. The Crop Journal 2017, 5, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnawal D, Bharti N, Maji D; et al. 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) deaminase-containing rhizobacteria protect Ocimum sanctum plants during waterlogging stress via reduced ethylene generation. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2012, 58, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grichko V P, Glick B R. Flooding tolerance of transgenic tomato plants expressing the bacterial enzyme ACC deaminase controlledby the 35S, rolD or PRB-1b promoter[J]. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2001, 39, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canarini A, Dijkstra F A. Dry-rewetting cycles regulate wheat carbon rhizodeposition, stabilization and nitrogen cycling. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2015, 81, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 8. Castrillo G, Teixeira P J P L, Paredes S H, et al. Root microbiota drive direct integration of phosphate stress and immunity. Nature 2017, 543, 513–518. [CrossRef]

- Grayston S J, Wang S, Campbell C D; et al. Selective influence of plant species on microbial diversity in the rhizosphere. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 1998, 30, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang Z C, Kozlowski T T. Water relations, ethylene production, and morphological adaptation of Fraxinus pennsylvanica seedlings to flooding. Plant and Soil 1984, 77, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabti E, Jha B, Hartmann A. Impact of seaweeds on agricultural crop production as biofertilizer[J]. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 14, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NING C, GAO P, WANG B; et al. Impacts of chemical fertilizer reduction and organic amendments supplementation on soil nutrient, enzyme activity and heavy metal content[J]. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2017, 16, 1819–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng X, Liu B, C; et al. Effect of pig manure on the chemical composition and microbial diversity during co-composting with spent mushroom substrate and rice husks. Bioresource technology 2018, 251, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaje V V, Sharma D K, Shivay Y S; et al. Long-term impact of organic and conventional farming on soil physical properties under rice (Oryza sativa)-wheat (Triticum aestivum) crop** system in north-western Indo-Gangetic plains. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 88, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng M Y, Li H M, Zhao J S; et al. Current situation and developmental trend of microbial fertilizer researches. Acta Agriculturae Jiangxi 2018, 30, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hong-peng Z, Pan-pan Z, Dong L I B L I; et al. Effects of uniconazole on alleviation of waterlogging stress in soybean. CHINESE JOURNAL OF OIL CROP SCIENCES, 2017, 39, 655. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zhi-Yong, et al.; et al. Effects of irrigation at flowering stage on soil nutrient and root distribution in wheat field. The Journal of Applied Ecology 2022, 12, 3328–3336. [Google Scholar]

- SHANGGUAN, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. SHANGGUAN. "Effect of nitrogen on root vigor and growth in different genotypes of wheat under drought stress. 37.6. Journal of Triticeae Crops 2017, 820–827. [Google Scholar]

- Lu W T, Jia Z K, Zhang P; et al. Effects of organic fertilization on winter wheat photosynthetic characteristics and water use efficiency in semi-arid areas of southern Ningxia. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science 2011, 17, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Ni T, Li J; et al. Effects of organic–inorganic compound fertilizer with reduced chemical fertilizer application on crop yields, soil biological activity and bacterial community structure in a rice—wheat crop** system. Applied soil ecology 2016, 99, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang Q, Yang G, Wang Y; et al. Illumina-based analysis of the rhizosphere microbial communities associated with healthy and wilted Lanzhou lily (Lilium davidii var. unicolor) plants grown in the field. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2016, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan M, Li J, Yan W; et al. Shifts in the structure and function of wheat root-associated bacterial communities in response to long-term nitrogen addition in an agricultural ecosystem. Applied Soil Ecology 2021, 159, 103852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarbad H, Constant P, Giard-Laliberté C; et al. Water stress history and wheat genotype modulate rhizosphere microbial response to drought. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2018, 126, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo T Z, Yuan L Z, Zhao Y Q. Liu J Y,Gu C. Effects of waterlogging on maize yield and the rhizosphere soil microorganism. Hubei Agric Sci 2014, 53, 505–507, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Evans S E, Wallenstein M D. Soil microbial community response to drying and rewetting stress: does historical precipitation regime matter ? Biogeochemistry 2012, 109, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger I M, Kennedy A C, Muzika R M. Flooding effects on soil microbial communities. Applied Soil Ecology 2009, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisner A, Leizeaga A, Rousk J; et al. Partial drying accelerates bacterial growth recovery to rewetting. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2017, 112, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HU R, ZHENG L, LIU H. Effects of straw returning on microbial diversity in rice rhizosphere and occurrence of rice sheath blight. Acta Phytophylacica Sinica 2020, 47, 1261. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Ke W J, Liu J; et al. Influence of water controlling depth on soil microflora and bacterial community diversity in paddy soil. Zhongguo Shengtai Nongye Xuebao/Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture 2019, 27, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N, Bradford M A, Jackson R B. Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology 2007, 88, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang G P, Ayiguli T H T, Wang R. Study on the diversity and community structure of salt tolerant bacteria in saline alkali soil in Wuerhe. Xinjiang J Microbiol 2021, 41, 17–26, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- AI C, SUN J, WANG X; et al. Advances in the study of the relationship between plant rhizodeposition and soil microorganism. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Fertilizers 2015, 21, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar]

- Pankratov T A, Ivanova A O, Dedysh S N; et al. Bacterial populations and environmental factors controlling cellulose degradation in an acidic Sphagnum peat. Environmental Microbiology 2011, 13, 1800–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu S, Gischkat S, Reiche M; et al. Ecophysiology of Fe-cycling bacteria in acidic sediments. Applied and environmental microbiology, 2010, 76, 8174–8183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates J D, Ellis D J, Gaw C V; et al. Geothrix fermentans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel Fe (III)-reducing bacterium from a hydrocarbon-contaminated aquifer. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 1999, 49, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kielak A, Pijl A S, Van Veen J A; et al. Differences in vegetation composition and plant species identity lead to only minor changes in soil-borne microbial communities in a former arable field. FEMS microbiology ecology 2008, 63, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Cong J, Lu H; et al. Community structure and elevational diversity patterns of soil Acidobacteria. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2014, 26, 1717–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López M, Meier-Kolthoff J P, Tindall B J; et al. Analysis of 1,000 type-strain genomes improves taxonomic classification of Bacteroidetes. Frontiers in microbiology 2019, 10, 2083. [Google Scholar]

- Feng D, Wu Z, Xu S. Nitrification of human urine for its stabilization and nutrient recycling. Bioresource technology 2008, 99, 6299–6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia-ying X U, **-rong Z, Jie W U. Medium-and long-term effects of the veterinary antibiotic sulfadiazine on soil microorganisms in a rice field. Journal of Agro-Environment Science 2020, 39, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Yang Y A, Yuan K N. Effects of three vitamins on the growth and physiological properties in wheat. Bull Sci Technol 1995, 11, 301–305, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L J, Liu Y G, Wang Y; et al. Bacterial community structure and diversity of sediments in a typical plateau lakeshore. Microbiol. China 2020, 47, 401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Kanokratana P, Uengwetwanit T, Rattanachomsri U; et al. Insights into the phylogeny and metabolic potential of a primary tropical peat swamp forest microbial community by metagenomic analysis. Microbial ecology 2011, 61, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana L H, Francis T B, Ferraro M; et al. Verrucomicrobiota are specialist consumers of sulfated methyl pentoses during diatom blooms. The ISME Journal 2022, 16, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon M H, Im W T. Flavisolibacter ginsengiterrae gen. nov., sp. nov. and Flavisolibacter ginsengisoli sp. nov., isolated from ginseng cultivating soil. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 2007, 57, 1834–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei W, Guan D, Ma M; et al. Long-term fertilization coupled with rhizobium inoculation promotes soybean yield and alters soil bacterial community composition. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1161983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva O L, Merkel A Y, Novikov A A; et al. Tepidisphaera mucosa gen. nov., sp. nov., a moderately thermophilic member of the class Phycisphaerae in the phylum Planctomycetes, and proposal of a new family, Tepidisphaeraceae fam. nov., and a new order, Tepidisphaerales ord. nov. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 2015, 65(Pt. 2), 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J Jiang Z, Huang X, Wang S; et al. Divalent manganese stimulates the removal of nitrate by anaerobic sludge. RSC advances 2024, 14, 2447–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).