Submitted:

24 January 2024

Posted:

25 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Regional inequalities in Central and Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans

3. Development of the post-socialist regions

4. Characteristics of the urban network

- The emergence of new states and their capital cities.

- Improved permeability of borders.

- The establishment of a “new neighborhood” [50].

5. Materials and Methods

| Search steps | Conditions | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Status | Active |

| 2. | Standardized legal form | Public limited company, Private limited company, Partnership, Branch, Foreign company, Public authority |

| 3. | Operating revenue (Turnover), using estimates (th USD) 1 | min=100, Last available year, exclusion of companies with no recent financial data and Public authorities/States/Governments |

| 4. | Number of employees, using estimates | min=100, max=160, Last available year, exclusion of companies with no recent financial data and Public authorities/States/Governments |

| 5. | World region/Country/Region in country | Albania, Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia |

6. Results

7. Discussion

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Braunerhjelm, P.; Ekholm, K. The Geography of Multinational Firms. 1998. [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, K.B.; Singhal, V.R.; Zhang, R. The Effect of Operational Slack, Diversification, and Vertical Relatedness on the Stock Market Reaction to Supply Chain Disruptions. Journal of Operations Management 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, T.; Singh, T.; Sinha, A. Location Strategy for Competitiveness of Special Economic Zones. Competitiveness Review an International Business Journal Incorporating Journal of Global Competitiveness 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovsky, L.; Harrison, R.; Simpson, H. University Research and the Location of Business R&D. The Economic Journal 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; Mudambi, R. MNEs as Border-Crossing Multi-Location Enterprises: The Role of Discontinuities in Geographic Space. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Rácz, S. Közép- És Délkelet-Európa Az Ezredforduló Óta. In A regionalizmus: az elmélettől a gyakorlatig: Illés Ivánra emlékezve 80. születésnapja alkalmából; Nemes Nagy, J., Pálné Kovács, I., Eds.; IDResearch Kft; Publikon: Pécs, 2022; pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Geldés, C.; Heredia, J.; Felzensztein, C.; Mora, M. Proximity as Determinant of Business Cooperation for Technological and Non-Technological Innovations: A Study of an Agribusiness Cluster. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R.; Frenken, K. Technological Relatedness and Regional Branching. In Beyond Territory: Dynamic Geographies of Knowledge Creation, Diffusion, and Innovation; 2012.

- Maré, D.C.; Graham, D.J. Agglomeration Elasticities and Firm Heterogeneity. Journal of Urban Economics 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwehumbiza, D.; Sakijege, T. Economic Benefits and the Geographic Aspect of Business Behaviour. Management Decision 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.; Bradshaw, M.J.; Coe, N.M.; Faulconbridge, J. Sustaining Economic Geography? Business and Management Schools and the UK’s Great Economic Geography Diaspora. Environment and Planning a Economy and Space 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachpazidu-Wójcicka, K. Small Firm’s Cooperation for Innovation With Other Firms and Research Units-Whether the Partner Matters for Product, Process, Marketing and Organizational Innovations? European Research Studies Journal 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojan, T.R.; Slaper, T.F. Are the Problem Spaces of Economic Actors Increasingly Virtual? What Geo-Located Web Activity Might Tell Us About Economic Dynamism. Plos One 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartik, T.J. “But For” Percentages for Economic Development Incentives: What Percentage Estimates Are Plausible Based on the Research Literature? 2018. [CrossRef]

- Amdam, R.P.; Bjarnar, O.; Berge, D.M. Resilience and Related Variety: The Role of Family Firms in an Ocean-Related Norwegian Region. Business History 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlay, H. Entrepreneurial and Vocational Education and Training in Central and Eastern Europe. Education + Training 2001. [CrossRef]

- Kornai, J. The Great Transformation of Central Eastern Europe: Success and Disappointment. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Gros, D.; Steinherr, A. Economic Transition in Central and Eastern Europe. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, O. The Economics of Post-Communist Transition. 1998. [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, K. Systemic Transformation in Poland and Eastern Germany: Two Versions of the Social Market Economy? Ekonomia I Prawo 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikas, B. TRANSFORMATIONS AND Regional EconomiC DEVELOPMENT I N Central and Eastern Europe: TYPICALITIES AND NEW PERSPECTIVES. Regional Formation and Development Studies 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuaresma, J.C.; Doppelhofer, G.; Feldkircher, M. The Determinants of Economic Growth in European Regions. Regional Studies 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T. Socio-Economic and Political Responses to Regional Polarisation and Socio-Spatial Peripheralisation in Central and Eastern Europe: A Research Agenda. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosker, M. The Spatial Evolution of Regional GDP Disparities in the ‘Old’ and the ‘New’ Europe. Papers of the Regional Science Association 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezinski, M. Determinants of Inequality in Transition Countries. Iza World of Labor 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann, R.; Ritzberger-Grünwald, D.; Schuberth, H. 30 Years of Transition in Europe: Looking Back and Looking Beyond in CESEE Countries; 2020.

- Eikemo, T.A.; Kunst, A.E.; Judge, K.; Mackenbach, J.P. Class-Related Health Inequalities Are Not Larger in the East: A Comparison of Four European Regions Using the New European Socioeconomic Classification. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2008. [CrossRef]

- Sethi, D.; Aldridge, E.; Rakovac, I.; Makhija, A. Worsening Inequalities in Child Injury Deaths in the WHO European Region. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamowicz, M. The Potential for Innovative and Smart Rural Development in the Peripheral Regions of Eastern Poland. Agriculture 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillitsch, M.; Asheim, B. Place-Based Innovation Policy for Industrial Diversification in Regions. European Planning Studies 2018, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdikos, V.; Chardas, A. European Union Cohesion Policy Post 2014: More (Place-Based and Conditional) Growth–Less Redistribution and Cohesion. Territory, Politics, Governance 2016, 4. [CrossRef]

- Szabo Paland Jozsa, V. and G.T. Cohesion Policy Challenges and Discovery in 2021–2027. The Case of Hungary. DETUROPE-The Central European Journal of Regional Development and Tourism 2021, 13, 66–100. [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.; Bobak, M. Social and Economic Changes and Health in Europe East and West. European Review 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovski, B.; Đokić, D.; Zekić, S.; Jurjević, Ž. Determining Food Security in Crisis Conditions: A Comparative Analysis of the Western Balkans and the EU. Sustainability 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovski, B.; Zekić, S.; Jurjević, Ž.; Đokić, D. The Agribusiness Sector as a Regional Export Opportunity: Evidence for the Vojvodina Region. International Journal of Emerging Markets 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusufi, G.; Bellaqa, B. Trade Barriers and Exports Between Western Balkan Countries. Naše Gospodarstvo/Our Economy 2019. [CrossRef]

- Brankov, T.; Matkovski, B. Is a Food Shortage Coming to the Western Balkans? Foods 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaze, N.M.; Wang, X. Is China’s Rising Influence in the Western Balkans a Threat to European Integration? Journal of Contemporary European Studies 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittová, Z.; Steinhauser, D. The International Economic Position of Western Balkan Countries in Light of Their European Integration Ambitions. Journal of Competitiveness 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikalović, G.M.; Molnar, D.; Josipović, S. The Open Balkan as a Development Determinant of the Western Balkan Countries. Acta Economica 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, B. Market Economies of the Western Balkans Compared to the Central and Eastern European Model of Capitalism. Croatian Economic Survey 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaj, E. European Integration, Economy and Corruption in the Western Balkans. European Journal of Economics and Business Studies 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmezic, M. Recalibrating the EU’s Approach to the Western Balkans. European View 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Krøijer, A. Fiscal Decentralization and Economic Growth in Central and Eastern Europe. Growth and Change 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley Scott, J. Post-Millennial Visegrad Four Geopolitics: Illiberalism and Positionality within the EU. DETUROPE-The Central European Journal of Regional Development and Tourism 2021, 13, 13–33. [CrossRef]

- Sávai, M.; Bodnár, G.; Mozsár, F.; Lengyel, I.; Szakálné Kanó, I. Spatial Aspects of the Restructuring of the Hungarian Economy between 2000 and 2019. DETUROPE-The Central European Journal of Tourism and Regional Development 2022, 14, 15–33. [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, H.; Zou, H.-F. Fiscal Decentralization and Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Study. Journal of Urban Economics 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E. Oates Fiscal Federalism; Edward Elgar Pub: Cheltenham, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hassink, R. Advancing Place-Based Regional Innovation Policies. In Regions and Innovation Policies in Europe: Learning from the Margins; 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hajdú, Z.; Horeczki, R.; Rácz, S. Changing Settlement Networks in Central and Eastern Europe with Special Regard to Urban Networks. In The Routledge Handbook to Regional Development in Central and Eastern Europe; 2019.

- Batrancea, L.; Nichita, A.; Balcı, M.A.; Akgüller, Ö. Empirical Investigation on How Wellbeing-Related Infrastructure Shapes Economic Growth: Evidence From the European Union Regions. Plos One 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkes, J. The Economic Structure and Performance of the Catchment Area of the Hungarian Regional Centers. DETUROPE-The Central European Journal of Tourism and Regional Development 2020, 12, 58–81. [CrossRef]

- Solarski, M.; Krzysztofik, R. Is the Naturalization of the Townscape a Condition of De-Industrialization? An Example of Bytom in Southern Poland. Land 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turok, I.; Mykhnenko, V. The Trajectories of European Cities, 1960–2005. Cities 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racz, S. Development Processes of Regional Centres in Central and Southeast Europe-From State Socialism to Dependent Market Economies. DETUROPE-The Central European Journal of Regional Development and Tourism 2019, 11, 92–100. [CrossRef]

- Gál, Z.; Lux, G. FDI-Based Regional Development in Central and Eastern Europe: A Review and an Agenda. Tér és Társadalom 2022, 36, 68–98. [CrossRef]

- Zdanowska, N. Metropolisation and the Evolution of Systems of Cities in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland Since 1950. Deturope–The Central European Journal of Regional Development and Tourism 2015, 7, 45–64. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Kacprzak, K.; Szafrańska, E. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected the Functioning of Tourist Short-Term Rental Platforms (Airbnb and Vrbo) in Polish Cities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Athanasopoulou, A.; Rink, D. Urban Shrinkage as an Emerging Concern for European Policymaking. European Urban and Regional Studies 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raźniak, P.; Winiarczyk-Raźniak, A. Did the 2008 Global Economic Crisis Affect Large Firms in Europe? Acta Geographica Slovenica 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocić, N. Culture-Led Urban Development vs. Capital-Led Colonization of Urban Space: Savamala—End of Story? Urban Science 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashnitsky, I.; Gunko, M. Spatial Variation of In-Migration to Moscow: Testing the Effect of Housing Market. Cities 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Bernt, M.; Großmann, K.; Mykhnenko, V.; Rink, D. Varieties of Shrinkage in European Cities. European Urban and Regional Studies 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, A.; Sm, A.; Berry, J.; McGreal, S. Central and Eastern European Property Investment Markets: Issues of Data and Transparency. Journal of Property Investment & Finance 2006. [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Voiculescu, S.; Jucu, I.S. Introduction: Changing Tourism in the Cities of Post-Communist Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmytkie, R. The Cyclical Nature of the Territorial Development of Large Cities: A Case Study of Wrocław (Poland). Journal of Urban History 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işik, O. Residential Segregation in a Highly Unequal Society: Istanbul in the 2000s. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gnatiuk, O. Demographic Dimension of Suburbanization in Ukraine in the Light of Urban Development Theories. Auc Geographica 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmytkie, R. Suburbanisation Processes Within and Outside the City: The Development of Intra-Urban Suburbs in Wrocław, Poland. Moravian Geographical Reports 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Zdyrko, A.; Bednarczyk, J. Semi-Natural Areas on Post-Mining Brownfields as an Opportunity to Strengthen the Attractiveness of a Small Town. An Example of Radzionków in Southern Poland. Land 2021. [CrossRef]

- Feruni, N.; Hysa, E.; Panait, M.; Radulescu, I.G.; Brezoi, A.G. The Impact of Corruption, Economic Freedom and Urbanization on Economic Development: Western Balkans Versus EU-27. Sustainability 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubenböck, H.; Gerten, C.; Rusche, K.; Siedentop, S.; Wurm, M. Patterns of Eastern European Urbanisation in the Mirror of Western Trends–Convergent, Unique or Hybrid? Environment and Planning B Urban Analytics and City Science 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živanović, Z.; Tošić, B.; Mirić, N.; Vračević, N. The Nature of Urban Sprawl in Western Balkan Cities. International Journal of Urban Sciences 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegańska, J.; Środa-Murawska, S.; Kruzmetra, Z.; Swiaczny, F. Peri-Urban Development as a Significant Rural Development Trend. Quaestiones Geographicae 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir, R.; Santos Ferreira, C.S.; Salvati, L. Long-Term Urbanization Dynamics and the Evolution of Green/Blue Areas in Eastern Europe: Insights From Romania. Sustainability 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikas, B. Urban Development and Property Management in the Context of Societal Transformations: Strategic Decision-making. International Journal of Strategic Property Management 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slach, O.; Bosák, V.; Krtička, L.; Nováček, A.; Rumpel, P. Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus Between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability. Sustainability 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, S.; Uvalic, M. FDI into Transition Economies: Are the Balkans Different? Economics of Transition 2014, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matković, G. The Welfare State in Western Balkan Countries: Challenges and Options. Stanovnistvo 2019, 57, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, A.; Cao, Y.; Liu, H. Does Suburbanization Cause Ecological Deterioration? An Empirical Analysis of Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunović, S.; Kosanović, R. Further Milestones in the Economic Developmentof South-Eastern Europe. SEER: journal for labour and social affairs in Eastern Europe: journal of the European Trade Union Institute 2019, 22, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo Acosta, E.J.; Salinas Aguilar, D.Y.; Pedroza, J.D. The Balkans as a Hierarchical Market Economy. European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerpentier, M.; Vanacker, T.; Paeleman, I.; Bringmann, K. Equity Crowdfunding, Market Timing, and Firm Capital Structure. The Journal of Technology Transfer 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajgar, M.; Berlingieri, G.; Calligaris, S.; Criscuolo, C.; Timmis, J. Coverage and Representativeness of Orbis Data. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tenucci, A.; Supino, E. Exploring the Relationship Between Product-Service System and Profitability. Journal of Management & Governance 2019. [CrossRef]

- Egyed, I.; Zsibók, Z. Labour Productivity in a Central and Eastern European Secondary City–Evidence From Regional and Firm-Level Data. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae European and Regional Studies 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rácz, S. Regionális Központok Innovációs Potenciálja Közép- És Délkelet-Európában. In Új Nemzeti Kiválóság Program Tanulmánykötet; Széchenyi István Egyetem: Győr, 2021; pp. 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Racz, S.; Egyed, I. Territorial Disparities and Economic Processes in Hungary: Editorial. DETUROPE-The Central European Journal of Regional Development and Tourism 2022, 14, 4–14. [CrossRef]

| Relations | Territory | Population | Urbanization | GDP | HDI | ||||||||

| Country | Last establishment | EU | NATO | km2 | Rank | Million (2019) | Rank | Urban pop. % | Rank | (PPP c.Int$) Billion (2021) | Rank | Value 2019 | Rank |

| Albania | 1912 (Ottoman Emp.) | candidate | member (2009) | 28 748 | 141 | 2,8 | 140 | 62,1 | 95 | 44 | 119 | 0.795 | 69 |

| Austria | 1920 (Austria-Hungary) | candidate | non member | 83 871 | 114 | 8,9 | 97 | 58,5 | 105 | 537 | 44 | 0.922 | 18 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1992 (SFRY) | potential candidate | candidate | 51 197 | 126 | 3,3 | 137 | 49 | 130 | 52 | 114 | 0.780 | 73 |

| Bulgaria | 1908 (Ottoman Emp.) | member state (2007) | member (2004) | 110 879 | 104 | 6,9 | 108 | 75,6 | 58 | 175 | 73 | 0.816 | 56 |

| Croatia | 1991 (SFRY) | member state (2013) | member (2009) | 56 594 | 125 | 4 | 131 | 57,6 | 104 | 120 | 85 | 0.851 | 43 |

| Czech Republic | 1993 (ČSFR) | member state (2004) | member (1999) | 78 865 | 116 | 10,7 | 87 | 74,1 | 61 | 461 | 47 | 0.900 | 27 |

| Hungary | 1920 (Austria-Hungary) | member state (2004) | member (1999) | 93 030 | 109 | 9,7 | 93 | 71,9 | 66 | 343 | 54 | 0.854 | 40 |

| Kosovo | 2008 (Serbia) | potential candidate | potential candidate | 10 908 | 170 | 1,8 | 153 | 40 | est. | 22 | 147 | 0.787 | 87 |

| Montenegro | 2006 (FRY) | candidate | member (2017) | 13 812 | 157 | 0,6 | 171 | 67,5 | 80 | 13 | 155 | 0.829 | 48 |

| North Macedonia | 1991 (SFRY) | candidate | member (2020) | 25 713 | 146 | 2,1 | 150 | 58,5 | 101 | 37 | 129 | 0.774 | 82 |

| Poland | 1918 (1945) | member state (2004) | member (1999) | 312 658 | 70 | 38,2 | 38 | 60 | 97 | 1364 | 20 | 0.880 | 35 |

| Romania | 1878 (1920) | member state (2007) | member (2004) | 238 391 | 82 | 19,3 | 62 | 56,4 | 111 | 636 | 36 | 0.828 | 49 |

| Serbia | 2006 (FRY) | candidate | potential candidate | 77 474 | 117 | 6,9 | 107 | 56,4 | 111 | 142 | 79 | 0.806 | 64 |

| Slovak Republic | 1993 (ČSFR) | member state (2004) | member (2004) | 49 037 | 128 | 5,5 | 119 | 53,8 | 119 | 190 | 70 | 0.860 | 39 |

| Slovenia | 1991 (SFRY) | member state (2004) | member (2004) | 20 273 | 151 | 2,1 | 149 | 55,1 | 118 | 86 | 97 | 0.917 | 22 |

| Country code | Size 2 | sum | Territory km2 | Population (million) | Number of firms per 1000 inhabitants | |||

| micro | small | medium | large | |||||

| BG | 30937 | 7806 | 2594 | 704 | 42041 | 110879 | 6.9 | 6.1 |

| HU | 26223 | 10160 | 2824 | 908 | 40115 | 93030 | 9.7 | 4.1 |

| SI | 3408 | 3047 | 1018 | 273 | 7746 | 20273 | 2.1 | 3.7 |

| HR | 8511 | 3587 | 1077 | 269 | 13444 | 56594 | 4.0 | 3.4 |

| RO | 39964 | 12510 | 3554 | 905 | 56933 | 238391 | 19.3 | 2.9 |

| CZ | 18294 | 9095 | 2649 | 500 | 30538 | 78865 | 10.7 | 2.9 |

| ME | 1083 | 380 | 94 | 24 | 1581 | 13812 | 0.6 | 2.6 |

| MK | 4151 | 991 | 245 | 56 | 5443 | 25713 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| AT | 5702 | 9849 | 2980 | 2585 | 21116 | 83871 | 8.9 | 2.4 |

| RS | 10286 | 4140 | 1271 | 299 | 15996 | 77474 | 6.9 | 2.3 |

| SK | 6486 | 4117 | 1379 | 449 | 12431 | 49037 | 5.5 | 2.3 |

| BA | 4262 | 1785 | 460 | 99 | 6606 | 51197 | 3.3 | 2.0 |

| PL | 20752 | 20920 | 9358 | 2839 | 53869 | 312658 | 38.2 | 1.4 |

| AL | 315 | 67 | 56 | 21 | 459 | 28748 | 2.8 | 0.2 |

| KV | 23 | 139 | 75 | 15 | 252 | 10908 | 1.8 | 0.1 |

| SUM | 180397 | 88593 | 29634 | 9946 | 308570 | |||

| 1 | The following rephrased statement employs a formal tone while discussing the turnover figures for the period of 2016-2021. Although the inclusion of active enterprises was a primary screening criterion, it was observed that the turnover data for some enterprises was incomplete for the final year within this timeframe. To address this issue, an imputation method was implemented, whereby missing data for the final year was supplemented with the closest available data from the preceding years. |

| 2 | The revenue figures presented herein are expressed in thousands of dollars and have been converted using the average euro-dollar exchange rate for the period of 2016-2021. It is important to note that this period differs from the one used in the previous footnote. It should be emphasized that the use of this exchange rate is necessary to provide a consistent and accurate representation of the revenue figures across different currencies. |

| 3 | As a result of the limited number of firms in Albania, it has been deemed appropriate to utilize NUTS2 (3 divisions) instead of the NUTS3 (12 divisions) levels. |

| 4 | As a result of the limited number of firms in Albania, it has been deemed appropriate to utilize NUTS2 (3 divisions) instead of the NUTS3 (12 divisions) levels. |

| 5 | see the first footnote |

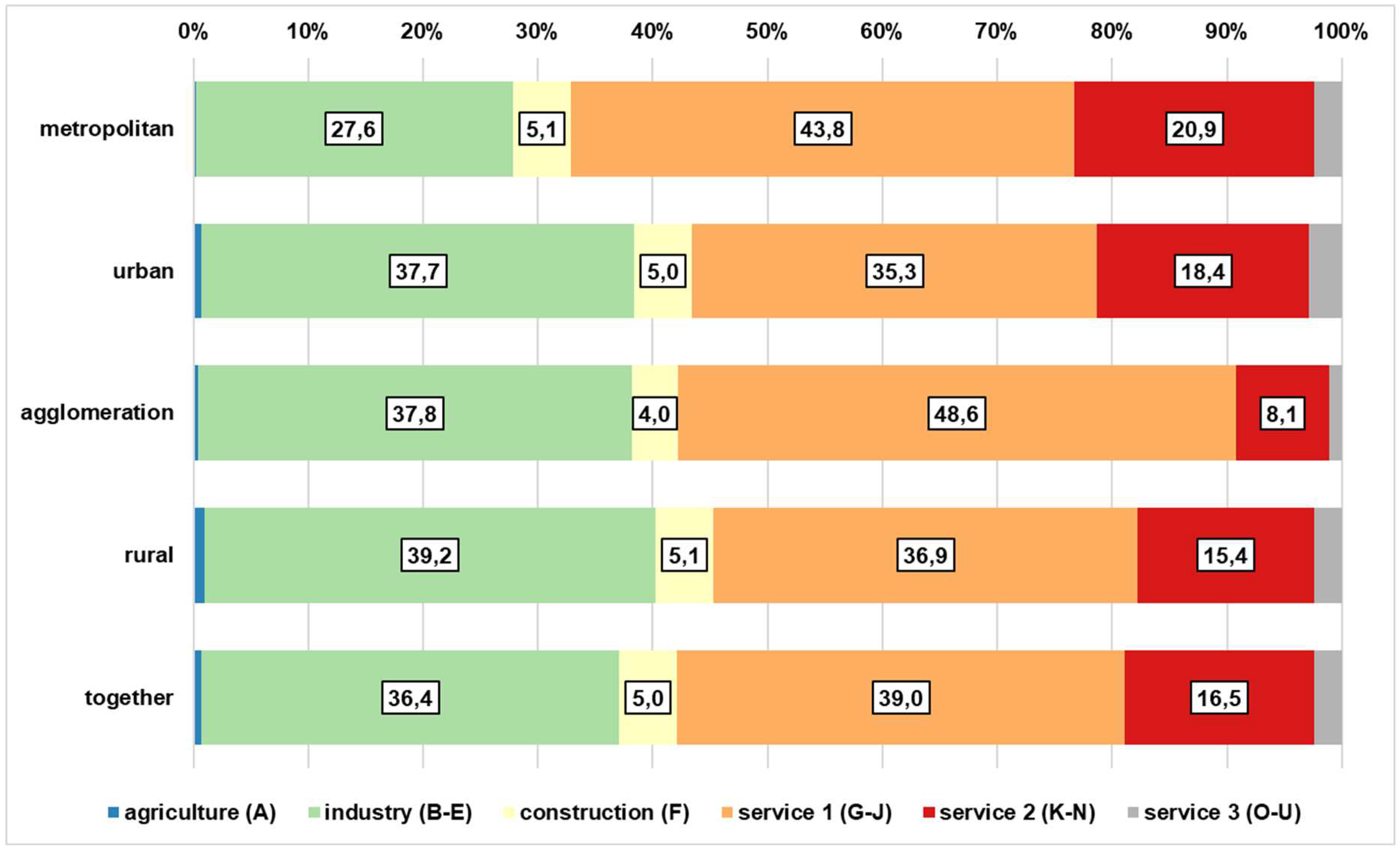

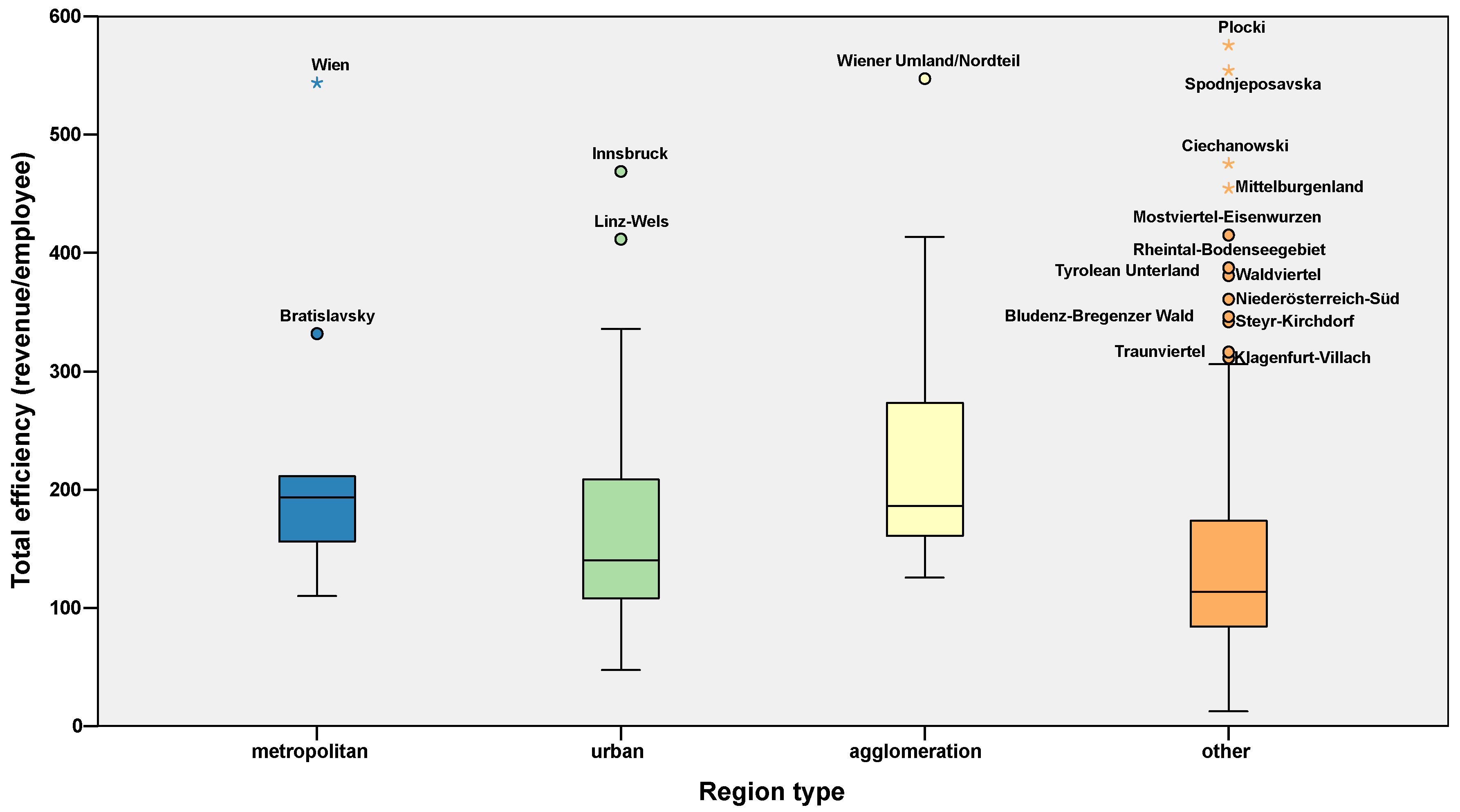

| 6 | Service activities are divided as follows: service 1-other private services; service 2-financial and business services; service 3-public services. |

| 7 | Types of regions were defined as follows: metropolitan–standalone NUTS 3 regions of capitals with more than one million inhabitants (Belgrade, Bucharest, Budapest, Prague, Sofia, Vienna, Warszawa) plus Bratislava and Zagreb; urban–NUTS 3 regions of citites with more than 250 000 inhabitants (city regions in Poland and Austria, ‘standard’ NUTS 3 regions in other countries plus smaller capitals (Ljubljana, Pristina, Skopje, Tirana); agglomeration–NUTS 3 regions containing FUAs of capitals, surrounding NUTS 3 regions of Polish city-regions, agglomerations of Linz and Graz, NUTS 3 regions of Upper Silesia conurbation, except Katowice; other–all other regions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).