Submitted:

24 January 2024

Posted:

25 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

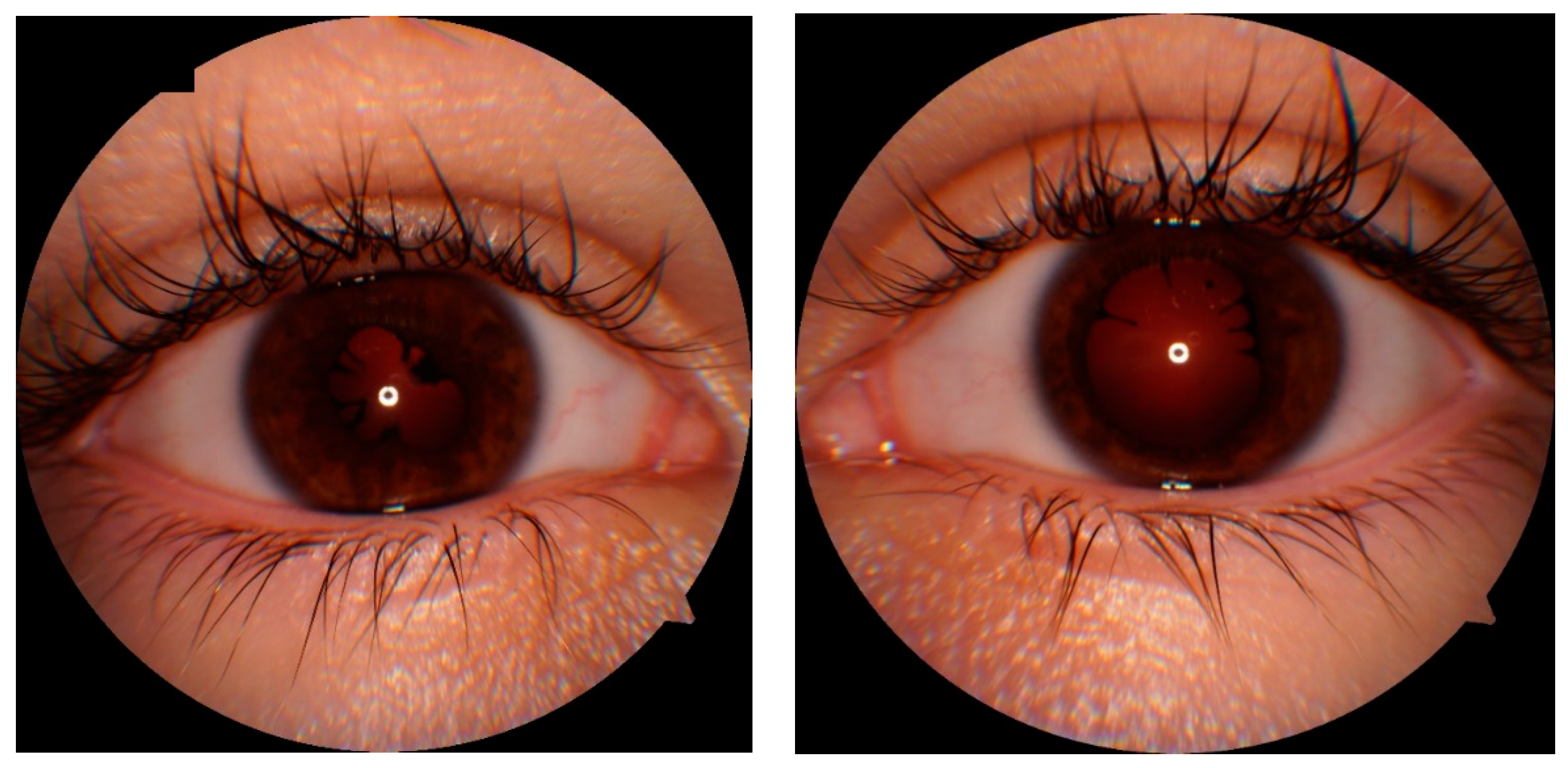

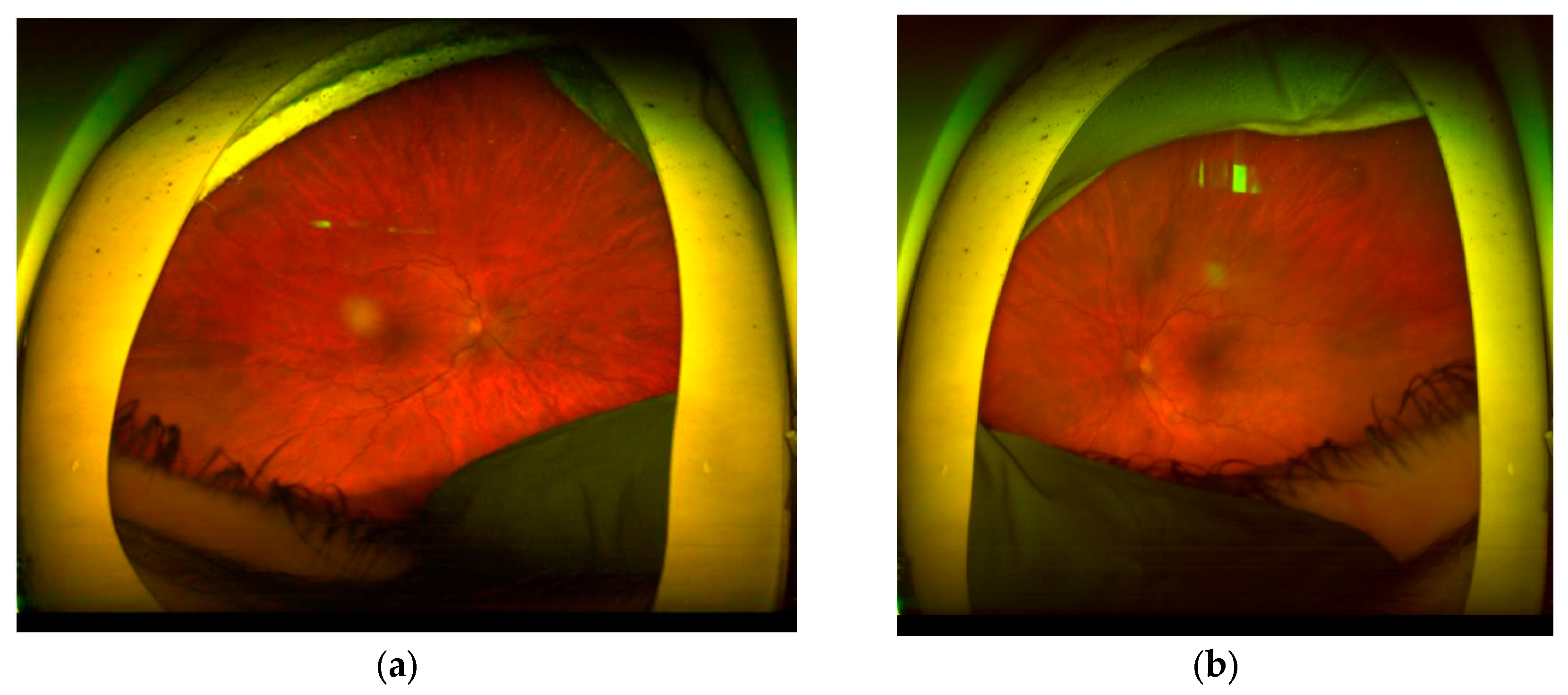

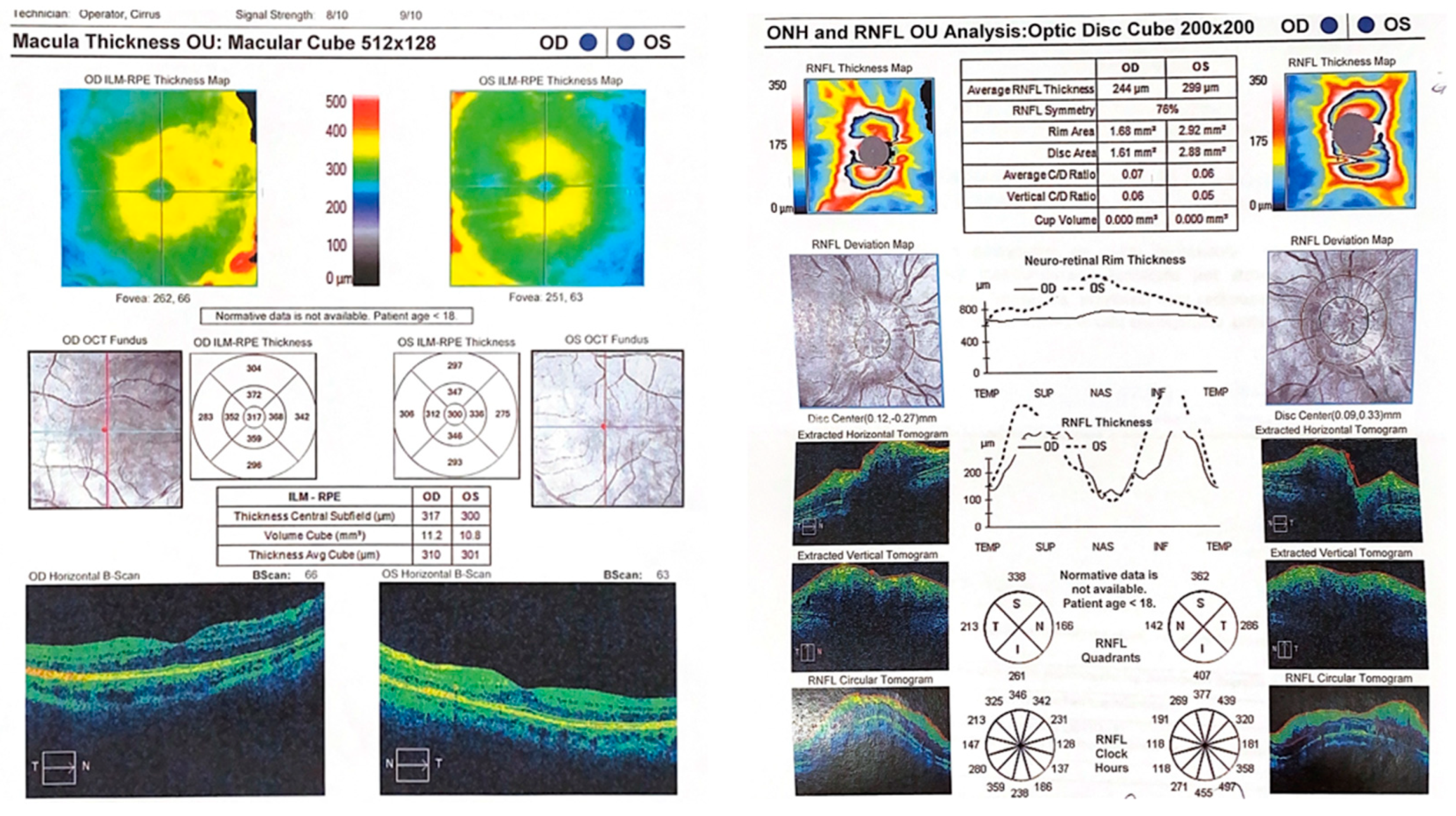

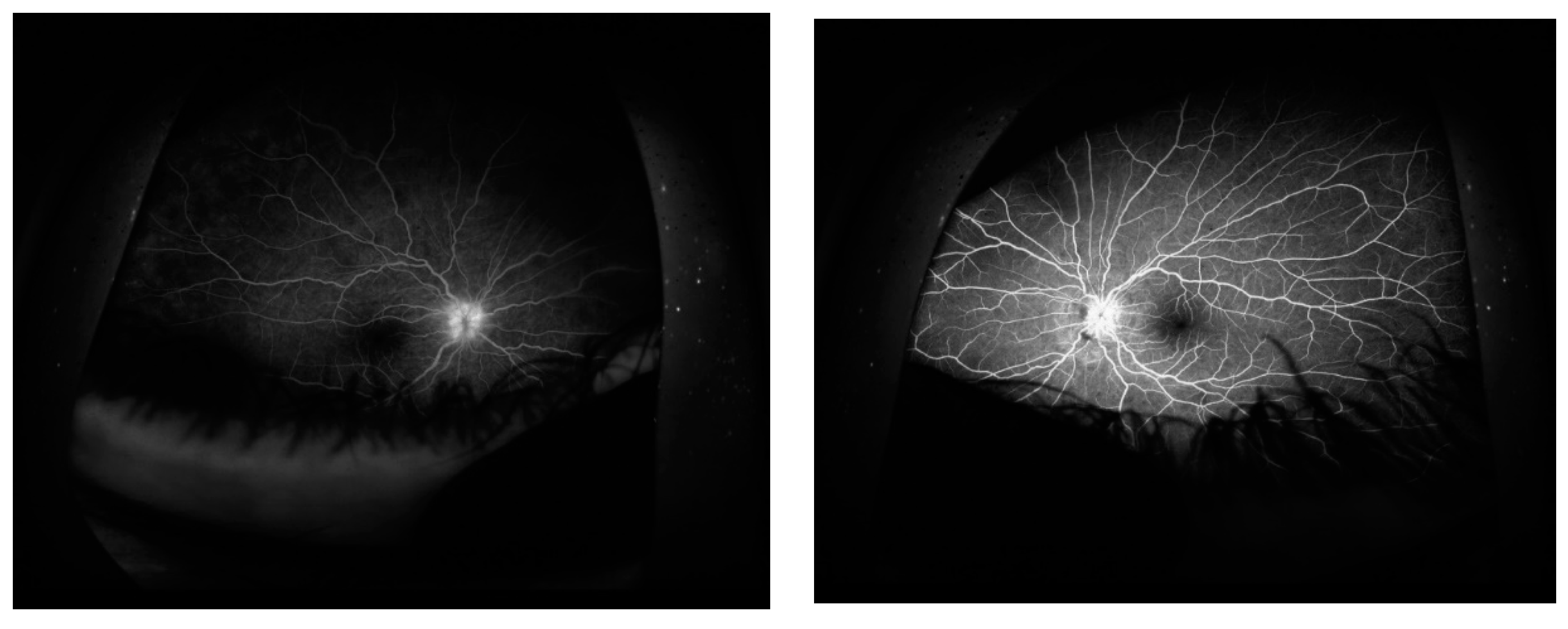

CASE DESCRIPTION

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghosh N, Nandi S, Saha I. A review on evolution of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants based on spike glycoprotein. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;105:108565. [CrossRef]

- Parums, DV. Editorial: The XBB.1.5 ('Kraken') Subvariant of Omicron SARS-CoV-2 and its Rapid Global Spread. Med Sci Monit. 2023;29:e939580. Published 2023 Feb 1. [CrossRef]

- Parums, DV. Editorial: A Rapid Global Increase in COVID-19 is Due to the Emergence of the EG.5 (Eris) Subvariant of Omicron SARS-CoV-2. Med Sci Monit. 2023;29:e942244. Published 2023 Sep 1. [CrossRef]

- Sperotto F, Gutiérrez-Sacristán A, Makwana S, et al. Clinical phenotypes and outcomes in children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome across SARS-CoV-2 variant eras: a multinational study from the 4CE consortium. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;64:102212. Published 2023 Sep 14. [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi E, Dubey AK, Teodori L, Ramakrishna S, Kaushik A. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: A next phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and a call to arms for system sciences and precision medicine. MedComm (2020). 2022;3(1):e119. Published 2022 Feb 11. [CrossRef]

- Alnahdi MA, Alkharashi M. Ocular manifestations of COVID-19 in the pediatric age group. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2023;33(1):21-28. [CrossRef]

- Worldmeter. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed September 22, 2022.

- Akbari M, Dourandeesh M. Update on overview of ocular manifestations of COVID-19. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:877023. Published 2022 Sep 13. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini SM, Abrishami M, Zamani G, et al. Acute Bilateral Neuroretinitis and Panuveitis in A Patient with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Case Report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021; 29(4):677-680. [CrossRef]

- Braceros KK, Asahi MG, Gallemore RP. Visual Snow-Like Symptoms and Posterior Uveitis following COVID-19 Infection. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2021; 2021:6668552. [CrossRef]

- Ichhpujani P, Singh RB, Dhillon HK, Kumar S. Ocular manifestations of COVID-19 in pediatric patients. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2023;15:25158414221149916. Published 2023 Mar 14. [CrossRef]

- Guo CX, He L, Yin JY, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of pediatric COVID-19. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):250. Published 2020 Aug 6. [CrossRef]

- Valente P, Iarossi G, Federici M, et al. Ocular manifestations and viral shedding in tears of pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a preliminary report. J AAPOS. 2020;24(4):212-215. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A., Kumari, E., Roy, A., & Bandyopadhyay, M. (2021). Ocular manifestations and clinical profile of multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Res Med Sci, 10(1), 173. [CrossRef]

- Madani, S. Acute and sub-acute ocular manifestations in pediatric patients with COVID-19: A systematic review. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol. 2022;11(1):11-18. Published 2022 Apr 1. [CrossRef]

- Ichhpujani P, Singh RB, Dhillon HK, Kumar S. Ocular manifestations of COVID-19 in pediatric patients. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2023;15:25158414221149916. Published 2023 Mar 14. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Garcia G Jr, Shah R, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and its beta variant of concern infect human conjunctival epithelial cells and induce differential antiviral innate immune response. Ocul Surf. 2022;23:184-194. [CrossRef]

- Willcox MD, Walsh K, Nichols JJ, Morgan PB, Jones LW. The ocular surface, coronaviruses and COVID-19. Clin Exp Optom. 2020;103(4):418-424. [CrossRef]

- Kyrou I, Randeva HS, Spandidos DA, Karteris E. Not only ACE2-the quest for additional host cell mediators of SARS-CoV-2 infection: Neuropilin-1 (NRP1) as a novel SARS-CoV-2 host cell entry mediator implicated in COVID-19. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):21. Published 2021 Jan 18. [CrossRef]

- Collin J, Queen R, Zerti D, et al. Co-expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the superficial adult human conjunctival, limbal and corneal epithelium suggests an additional route of entry via the ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2021;19:190-200. [CrossRef]

- Zhong Y, Wang K, Zhu Y, et al. Ocular manifestations in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021;44:102191. [CrossRef]

- Eissa M, Abdelrazek NA, Saady M. Covid-19 and its relation to the human eye: transmission, infection, and ocular manifestations. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023;261(7):1771-1780. [CrossRef]

- Hu K, Patel J, Swiston C, Patel BC. Ophthalmic Manifestations of Coronavirus (COVID-19). In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; May 24, 2022.

- Soni A, Narayanan R, Tyagi M, Belenje A, Basu S. Acute Retinal Necrosis as a presenting ophthalmic manifestation in COVID 19 recovered patients. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(4):722-725. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Chimal LG, Cuevas GG, Di-Luciano A, Chamartín P, Amadeo G, Martínez-Castellanos MA. Ophthalmic manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 in newborn infants: a preliminary report. J AAPOS. 2021;25(2):102-104. [CrossRef]

- Diwakar J, Samaddar A, Konar SK, et al. First report of COVID-19-associated rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Mycol Med. 2021;31(4):101203. [CrossRef]

- Ganesh SK, Mohanan-Earatt A. An analysis of the clinical profile of patients with uveitis following COVID-19 infection. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(3):1000-1006. [CrossRef]

- Merticariu CI, Merticariu M, Cobzariu C, Mihai MM, Dragomir MS. Pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome induced Panuveitis associated with SARS-CoV- 2 infection: What the Ophthalmologists need to know. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2022;66(2):198-208. [CrossRef]

- Yeo S, Kim H, Lee J, Yi J, Chung YR. Retinal vascular occlusions in COVID-19 infection and vaccination: a literature review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023;261(7):1793-1808. [CrossRef]

- Shiroma HF, Lima LH, Shiroma YB, et al. Retinal vascular occlusion in patients with the Covid-19 virus. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2022;8(1):45. Published 2022 Jun 23. [CrossRef]

- Seirafianpour F, Mozafarpoor S, Fattahi N, Sadeghzadeh-Bazargan A, Hanifiha M, Goodarzi A. Treatment of COVID-19 with pentoxifylline: Could it be a potential adjuvant therapy?. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):e13733. [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis MT, Cesarone MR, Belcaro G, Incandela L, Steigerwalt R, Nicolaides AN, Griffin M, Geroulakos G. Treatment of retinal vein thrombosis with pentoxifylline: a controlled, randomized trial. Angiology. 2002 Jan-Feb;53 Suppl 1:S35-8. PMID: 11865834.

- Mostafa-Hedeab G, Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Jeandet P, Saad HM, Batiha GE. A raising dawn of pentoxifylline in management of inflammatory disorders in Covid-19. Inflammopharmacology. 2022;30(3):799-809. [CrossRef]

- Shivpuri A, Turtsevich I, Solebo AL, Compeyrot-Lacassagne S. Pediatric uveitis: Role of the pediatrician. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:874711. Published 2022 Aug 1. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).